Abstract

This study empirically examined whether underwriters’ reputations affect the sustainability of newly listed firms, focusing on firm delisting risk using survival analysis. It was hypothesized that newly listed firms with more reputable underwriters would prove more sustainable, and this hypothesis was tested using a sample of firms that were newly listed on the Korea Composite Stock Price Index (KOSPI) and the Korea Securities Dealers Association Automated Quotation (KOSDAQ) markets in South Korea between 2001 and 2012. The data collected and used to test the aforementioned hypothesis were from 2001 to 2017. The analysis showed that newly listed firms with more reputable underwriters have lower delisting risk. This implies that newly listed firms with more reputable underwriters enjoy greater sustainability. This study meaningfully contributes to sustainability research by rationally explaining why underwriters’ incentives to maintain their reputations improve newly listed firms’ business and financial status. This study differs from other management studies in that it produced meaningful results using survival analysis, which has not been widely used in conventional management studies. Its findings also contribute in terms of identifying the possibility that underwriters’ reputations can be used as a predictor of the possibility of delisting newly listed companies.

1. Introduction

Business entities accumulate revenues through operating activities and often reinvest revenues in operating activities by capitalizing on them to acquire additional sources of revenue. These processes allow them to continue their operations. However, entities may not be able to generate sustainable profits solely through the lifecycles of their own products and services; they may need to engage in investment activities separate from their operating activities to produce and supply better goods to the market. Generating immediate profit by making such investments can prove difficult. In such cases, entities need significant amounts of money to support their ongoing operations and growth, and one method they use before being listed on the capital market is acquiring financing through new listings [1].

From firms’ perspectives, the success of new listings involves not only raising funds but also establishing foundations for future growth potential to solidify the possibility of continuing operations. The success of such new corporate listings, which are important to businesses, is not based on the mechanical fulfillment of legal requirements but on information about the business performance of listed companies and their future prospects ex ante. Firms must therefore select underwriters to oversee objective assessments of their operating and financial positions with respect to the listing process [2]. Moreover, the selection of pre-listed brokers (underwriters) is mandated by law.

Firms initiate the listing of their businesses by selecting underwriters to assist in establishing their new listings faithfully. However, stakeholders in the capital market do not have sufficient information about pre-listed firms and are expected to use data collected indirectly while making investment decisions. This study examined many indirect elements, including the reputations of underwriters deeply involved in new listing processes.

Reputations are not formed rapidly; they develop cumulatively over long periods. The factors that impact underwriters’ reputations include how effectively they complete new listing processes, whether firms arrange listings successfully, whether listings fail due to problems in listing processes, and whether the information is listed on the market as required. Furthermore, underwriters’ reputations can affect the performance of newly listed companies and their abilities to conduct long-term operating activities in the market as follows: Underwriters with excellent reputations will increase the future viability of the companies that employ them [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In this regard, prior studies are limited to how the reputations of underwriters affect the financial reporting and performance of newly listed firms. In addition, few studies have directly analyzed the delisting risk of newly listed firms and, ultimately, its impact on the sustainability of firms within the capital market.

Considering these factors, this study aimed to verify that underwriter reputation can serve as a basic evaluative criterion, even in part, for newly listed firms. Specifically, the viability of newly listed entities was empirically analyzed using two techniques (i.e., Kaplan–Meier analysis [14] and Cox proportional hazards model [15]) of survival analysis using underwriter reputation as a basis for assessing firms’ operating and financial fundamentals—important indicators for investors. These analyses were conducted using a sample of companies listed on the Korea Composite Stock Price Index (KOSPI) and the Korea Securities Dealers Association Automated Quotation (KOSDAQ) markets between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2012.

Prior studies that analyzed the relationship between underwriters’ reputations and newly listed firms generally studied the performance or financial reporting of the newly listed firms after listing. However, few studies have directly commented on the relationship between the reputation of the underwriter and the viability of the company in charge of the listed business. Therefore, this study is significant in terms of extending the discussion of the role of the underwriter’s reputation mentioned in prior studies.

The results of this study contribute in terms of identifying the possibility that the underwriter’s reputation can be used as a predictor of the possibility of delisting newly listed firms. In the capital market, investors often hesitate to make timely investment decisions due to insufficient information if they want to invest in newly listed companies. In addition, there is a tendency for active investment not to be made due to the possibility of misinformed investment results caused by a lack of information. Therefore, this study can contribute to the continued development of the capital market by helping to ensure that investors’ decisions can be made actively.

In addition, this study is differentiated from other business studies in that it has produced meaningful results using survival analysis, which has not been widely used in conventional business studies. Whether a firm is delisted and the period of listing can be analyzed by ordinary least square (OLS) regression, logit analysis, and probit analysis, which are generally widely used in business studies, but it is believed that survival analysis offers a more sophisticated method of analysis. Therefore, this study differs from existing management studies, as it has produced significant results through more sophisticated analyses. Finally, the study is significant in that the underwriter’s reputation can provide important information in terms of corporate sustainability in the capital market. From a management standpoint, sustainability requires a combination of factors that keep a company’s growth sustainable, and it is generally discussed in terms of the environment, society, and economy. Generally, the environmental and social aspects discuss the ethical behavior of a company, but the ethical behavior of a company is an essential element of economic support based on the profits of the company [16,17]. After all, the most important point in sustainable management concerns whether the activities of a company actually bring about the ultimate increase in value. This means that enabling sustainable management must precede the survival of companies within the capital market. Therefore, the study of factors that affect the sustainability of an enterprise has important meaning in itself. The sustainability of the capital market can be said to be closely related to the sustainability of companies. A company’s sustainability does not simply mean that it maintains long-term operations without facing delisting within the capital market. The delisting of a firm refers to the loss of shareholders’ wealth, the loss of employees working for the entity, and the occurrence of a chain of damages to officials with direct and indirect interests, such as other companies that have business relations with the entity. This study, which analyzed the role of reputation on factors affecting the possibility of a company being delisted, has significant implications in that it could ultimately affect the sustainability of the capital market and the development and sustainability of the members of society that require capital by causing serious damage to the national economy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews prior studies and describes the development of this study’s hypothesis. Section 3 explains the study’s sample selection process and the empirical model and variables of the hypothesis. Section 4 presents and interprets the descriptive statistics to provide an overview of the characteristics of the study’s variables and explain the analysis results of the models established in Section 3 to analyze the hypothesis statistically. Finally, Section 5 discusses the study’s conclusions and contributions.

2. Prior Literature and Hypothesis Development

Prior to the completion of new listings, information regarding newly listed companies is generally not disclosed or disclosed to the market to a very limited degree. Since information about companies seeking listings is limited, investors who are willing to invest in newly listed companies have less information about these companies than internal stakeholders. Thus, asymmetry exists. Unless they manage to obtain private information related to the companies, investors must rely on the limited information disclosed by the company in making investment decisions, and this information is usually simply what the law requires companies to disclose. Moreover, this information is likely to be financial in nature. In addition, internal stakeholders may be aware that information about the companies is actually limited in the market, which incentivizes companies to leverage the information asymmetry between themselves and investors [18] in their favor. This includes upward earnings management. In this context, existing research has shown that companies about to be listed tend to use information asymmetry by engaging in upward earnings management [11,13,19,20,21,22,23]. Therefore, investors believe that any other information they can secure before making investment decisions only based on public financial information acts as an incentive for them to reflect on their own decisions [3,24,25].

Companies pursuing new listings should appoint underwriters who directly participate in their listing processes and oversee listing procedures. Underwriters are usually selected from among investment banks [26,27,28,29,30]. They help companies interested in becoming newly listed on the market and their related stakeholders. They first closely examine newly listed companies and provide information to potential investors. This helps investors by reducing the effect of problems caused by information asymmetry in the market [3,27,31,32,33,34]. Moreover, in this process, underwriters help facilitate investment in newly listed companies and ensure the successful listing of new issues by completing all requisite steps, including the legal procedures necessary in the new listing process.

Underwriters are responsible for addressing the inevitable information asymmetry between companies and their stakeholders, and they are especially responsible for reducing the principal–agent problem [3,31,32,34,35]. In other words, underwriters must carefully observe the newly listed companies that nominate them. They help solve information asymmetries by providing interested parties with the information they acquire through observation. Underwriters also advise companies regarding legal issues related to the new listing of companies and help initial public offering (IPO) companies successfully complete their listings by overseeing them. Due to their deep involvement with newly listed companies and their listing processes, underwriters are aware of whether newly listed companies accurately represent their accounting information and financial status [5,8,36,37,38]. If they do not, the underwriters in charge of listing the businesses presumably have incentives to correct companies’ accounting information or financial status before the listings are revealed to be inappropriate.

In fact, it has been reported that companies facing new listing or capital increase tend to see their share prices highly valued from the upward management of their earnings, the most commonly cited indicator of an entity’s performance assessment, by making them appear superior. For those that have upward management of earnings, earnings tend to be reversed in subsequent years, resulting in a sharp decline in share prices as well [19,20,39]. In addition, a company that has newly listed or raised capital through earnings management or improper disclosure may be required to take legal responsibility by later being sued by shareholders in the event of a decline in earnings or share prices that are either listed or post-reward performance indicators [40]. If investors determine that they have received incorrect information about newly listed companies before making an investment decision or that they have not performed their underwriter duties faithfully, underwriters will immediately suffer damage to their reputation. In this case, the underwriter will not be able to generate continued profits in the future, as it will become difficult to import work from companies that want to be newly listed in the future. In addition to matters related to future work, there is also the possibility of being audited by relevant agencies or sued in class action suits, which is an important consideration for the underwriter [11,41]. Furthermore, it is believed that reputation as an element will be considered more sensitive for underwriters that are investment banks with higher reputation and a larger size. This is because if an investment bank fails to perform properly as an underwriter and disappoints investors in a newly listed company, it will have to take greater risks because it has more to lose than an underwriter with lower reputation and a smaller size.

Therefore, it can be said that underwriters participating in new listing processes control the upward earnings management and inadequate or inappropriate disclosure of newly listed companies [5,13,23,42,43,44]. In this respect, it is believed that underwriters play an important role in helping both newly listed companies and related stakeholders through decreasing the information asymmetry between them. Prior research related to the impact of underwriters’ reputation has studied the effect of underwriters’ reputation on the process of issuing corporate bonds [35], the impact of underwriters’ reputation on the earnings management of companies before seasoned equity offerings [41,45], and the impact of underwriters’ reputation on the earnings management of newly listed companies [11]. Additionally, they argued that reputable underwriters play a positive role in the capital market by effectively reducing information asymmetry. Through the above-mentioned tasks, underwriters can help connect potential investors in the stock market with newly listed companies. Moreover, underwriters are evaluated in the market based on how well they perform these tasks. In fact, the appointment of an underwriter is conducted through competition among a limited number of investment banks within the capital market, an event that directly affects the profits that individual investment banks can secure in the future and even their survival. However, this is not chosen randomly by a company that wants a new listing but based on the reputation factors formed by the result of the listing performance of a newly listed company, in which individual investment banks are in charge of their work as the underwriter (i.e., the trends of profit and stock prices) [34,35].

According to the Supervisory Policy Manual of Hong Kong’s financial authorities, reputation refers to the aggregate of beliefs, opinions, and brand images that are solidified based on stakeholder expectations and experience of the firm. Reputation is an intangible asset formed by the expectations of various stakeholders that affects the profitability or stock price of a firm and, in some cases, responds sensitively to the effects of uncontrolled external factors. For financial institutions in particular, reputation is formed not only by their financial soundness but also by a combination of all the environmental factors that create an image of a company, such as consumers’ trust, social responsibility, and compliance with regulations. As an underwriter, the investment bank has the characteristic of generating profits by providing intangible services to the market, so it is expected that its reputation, and its maintenance, is relatively more important.

Indeed, financial institutions with good reputations have a positive impact on relevant stakeholders as well. A good reputation serves to induce more consumers to purchase services provided by financial institutions. In addition, the trust formed based on the reputation of the financial institution allows financial institutions to secure additional and continuous profits in terms of maintaining their business relationships with companies in partnership and expanding their relationships with new ones. This could ultimately lead to the increased value of the financial institution in question, and a high reputation for financial institutions has a net function in that it can also lead to faith in companies with which it has business relationships.

More specifically, underwriters’ reputations are formed based on the following criteria: First, transparency in the disclosure of information; second, the appropriateness of public offering prices for newly listed company shares; and third, whether stock trading has been successfully accomplished by meeting market requirements. The extent to which underwriters meet these criteria affects the successful completion of listing procedures for newly listed companies. In addition, underwriters have sufficient incentives to carry out their duties in good faith; whether or not they do so will likely affect their reputations and determine whether they can survive in the market in the long term [12].

Thus, the possibility of delisting newly listed companies is closely related to the financial conditions of the companies themselves before, during, and after the listing periods and the companies’ positions in relation to industry conditions [46]. An examination of the financial and operational fundamentals of newly listed companies in relation to underwriter incentives indicates that underwriters will improve the soundness of companies by performing new listing procedures thoroughly and thereby reducing the possibility of delisting [47]. Studies on the possibility of delisting newly listed companies have mainly focused on factors related to the companies themselves, for example, the impact of earnings management on the possibility of delisting newly listed companies [22,48,49,50]. However, only a few studies have examined the viability of newly listed companies by underwriters who are responsible for all business related to the listings themselves as well as the newly listed companies.

Given this gap in the current research, this study focused on the significant impact of underwriters on the financial and legal soundness of newly listed companies, empirically analyzing the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The sustainability of newly listed firms will be higher if the reputations of their underwriters are higher.

3. Research Design

3.1. Measurement of an Underwriter’s Reputation

The main variable used in this study was a measure of underwriter reputation. Therefore, several variables related to underwriter reputation were measured and included in the model as independent variables.

However, past studies have not developed generally used indicators in this regard. Most studies on the effects of reputation in capital markets have been conducted in the United States, and researchers have examined reputation mainly in relation to venture capital, focusing on the period between the establishment of venture capital companies and the commencement of research for reputation indicators [51,52,53]. In addition, prior studies related to underwriter reputation have tended to measure reputation in one of two ways [3,4,11,33,54]. Carter and Manaster [3] and Carter et al. [33], for example, measured reputation based on data presented in the tombstone announcement, assuming that the order in which the names of the underwriters appeared in the announcement represented their reputational ranks. Meanwhile, Megginson and Weiss [4] and Aggarwal et al. [54] focused on relative market share, identifying the extent of individual underwriters’ public offerings as a reputation measure.

More specifically, studies measuring the reputations of underwriters have examined the relationship between the reputations of underwriters and both the earnings management of newly listed companies [12] and the conservatism of newly listed companies [55]. These studies have measured the reputations of underwriters using two methods based on the approach developed by Megginson and Weiss [4]. In the first method, researchers used the number of IPO business duties and the total number of IPOs as a yearly measure of underwriter reputation. In the second method, researchers followed Megginson and Weiss [4] in using the quartile, which standardizes the relative ratios of job openings to four ranks, as a measure of underwriter reputation.

Based on the results of prior studies, this study collected data related to newly listed companies that were disclosed via the public disclosure system (KRX: Korea Exchange) and used this data to measure underwriter reputation. Specifically, the measurement of reputation was based on the total number of newly listed companies and the volume using the won amount of public offerings for the total number of newly listed companies in the previous year. The ratio of the number of individual underwriters to the total number of newly listed companies for each year was calculated as one measure of the underwriter reputation. Moreover, the ratio of the won amount of individual underwriters to the total won amount of newly listed companies for each year was calculated as a second measure of underwriter reputation. In addition, the ratios of these performances to the total number of new listings using the performance of individual underwriters or the performance of underwriters were calculated as representative underwriters [56,57], and the results were used as additional reputation measures. Lastly, the rankings of individual underwriter performances were compared with the total number of listed appointments, and the individual underwriter performances were used as representative lead underwriters compared with the total number of listed appointments as another measure. In the event that there were multiple underwriters of newly listed companies announced on the KRX’s public disclosure system, news related to individual listed companies was searched, and representative underwriter data were hand collected.

3.2. Sample Selection

This study investigated newly listed companies in South Korea’s KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets between 2001 and 2012. The data on the newly listed companies were collected through the KRX. Survival analysis requires information related to survival periods (i.e., the period from when a company was first listed on the market to when it was delisted). For companies listed after 2013, this period was too short to include them for survival analysis, so they were excluded [58].

The data collected for the empirical analysis of newly listed companies in the study period were from between 2000 and 2017, and the data used to measure underwriter reputation were published in the Korea Investor’s Network for Disclosure System (KIND) provided by the KRX between 2000 and 2011. In addition, the financial data of newly listed companies used in the research were from the 2001–2017 period and collected through the Korea Information Service Value (KIS-VALUE) provided by NICE Information Service Co., Ltd. Finally, companies were excluded from the final sample if the complete data could not be obtained from the database. Companies belonging to the financial and real estate industries differed significantly from those in other industries and were thus excluded from the final sample. Therefore, the final sample used in this study included 477 firms on a firm-year basis.

3.3. Research Model

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the reputations of underwriters who oversee all listing process business affect the future delisting of newly listed companies on the KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets in South Korea. More specifically, in this study, two survival analysis techniques were used to examine the relationship between the reputation of IPO underwriters and the potential delisting of newly listed companies.

The first technique used was the Kaplan–Meier analysis [14], which measures the survival probability at each event occurrence (death, in this case, is delisting), by arranging survival period data from the shortest to the longest. Using this method, survival probabilities were calculated every time an event occurred without distinguishing observation periods at regular intervals, so the time intervals of observation periods were irregular. This analytical method is useful even if the number of samples is small. In this study, the data were divided into several groups based on the reputations of the underwriters, and the risk curves for each group were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier analysis. In this way, the hypothesis of whether there was a statistically significant difference in the delisting rates between the groups was first tested.

The second technique used was the Cox proportional hazards [15] model. This analytical model can address the shortcomings of the Kaplan–Meier analysis. It simply compares the differences between groups without considering other factors that may have statistically significant impacts on reputation and potential for delisting. In addition, the Cox proportional hazards model is useful because it uses censored data that cannot be observed by the end of the research period.

The research model established to apply the Cox proportional hazards model was as follows:

| Definition of Variables | |

| 1. | The probability that a company that existed until Time t will be delisted at Time t per unit hour |

| 2. | Baseline hazard: Probability of delisting when the covariates are all 0 |

| 3. exp(z) | Factors considered to have an impact on corporate delisting |

| Definition of Independent Variables (REPU: Reputation) | |

| 1. NUM | Number of successful public offerings a year before the IPO by the underwriter of the newly listed firms |

| 2. NUM_RATIO | Ratio of the number of the underwriter’s public offerings of newly listed firms in the year before the listing |

| 3. NUM_ORDER | Underwriter’s ranking measured (descending) by the number of public offerings made before the new firm’s listing |

| 4. AMO | Amount of successful public offerings a year before the IPO by the underwriter of the newly listed firms to be listed (Unit: Won) |

| 5. AMO_RATIO | Ratio of the amount of the underwriter’s public offerings in the year before the new firm’s listing |

| 6. AMO_ORDER | Underwriter’s ranking measured (descending) by the amount of public offerings before the new firm’s listing |

| 7. L_NUM | Number of successful public offerings a year before the IPO by the underwriter of the newly listed firms to be listed in the case of a representative underwriter |

| 8. L_NUM_RATIO | Ratio of the number of the underwriter’s public offerings of newly listed firms in the year before the listing in the case of a representative underwriter |

| 9. L_NUM_ORDER | Underwriter’s ranking measured (descending) by the number of public offerings made before the new firm’s listing in the case of a representative underwriter |

| Definition of Control Variables | |

| 1. IPO_VOL | Total number of public offerings at the time of the firm’s new listing |

| 2. SALES | Natural log of total sales |

| 3. SIZE | Natural log of total assets |

| 4. LEV | Total debt divided by total assets |

| 5. C_RATIO | Current liabilities divided by current assets |

| 6. ROA | Net income divided by total assets |

| 7. AGE | The newly listed firm’s establishment year minus the listing year |

| 8. OCF | Natural log of operating cash flow |

| 9. DA | Discretionary accrual calculated by the Jones [59] model |

| 10. AUDIT_DUM | 1 if newly listed company is from a BIG 4 firm and 0 otherwise |

| 11. YD | Year dummy |

The Cox proportional hazards model functions as follows. Based on the equal sign, the left side of the Cox model implies the possibility of delisting the company, which is called the hazard function ratio. The right side of this model is then expressed as the product of exp(z), which considers the baseline hazard function () and the variables that may affect the delisting potential. This statistical analysis reveals whether the variables of interest still affect the likelihood of survival, even after controlling for the influence of other variables that may affect the likelihood that the company will be delisted. Thus, this technique considers all of the possible control variables, enabling us to analyze the effect of the variables of interest on survival probability in depth in comparison with Kaplan–Meier analysis, which considers only the effect of the variables of interest on survival probability.

The following points about the independent variables in this study warrant attention. As noted in Section 2, if underwriters are thoroughly involved in the listing processes for newly listed companies, considering market assessments of their work experience or reputations, the newly listed companies will remain in sound financial positions and provide appropriate accounting information to the market. The underwriters of such newly listed companies will have positive reputations, and the market’s optimistic views of well-reputed underwriters will carry over to the newly listed businesses. This will presumably have a positive effect on operating activities, decreasing the likelihood that such companies will be delisted. As a result, it can be reasonably predicted that companies with more reputable underwriters will have lower delisting rates. In addition, it is expected that the estimates of the major variables (i.e., the underwriters’ reputation measures) will show a negative relationship with the delisting rate.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study as well as the mean values for both the surviving and delisted groups of newly listed firms. Panel A reports the descriptive statistics obtained without dividing the used variables into individual groups. Panel B shows the group averages by dividing the companies used in the study into a surviving group and a delisted group as well as the results of t-test-based analyses of the significant differences in the means of each group.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

Panel A presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study’s empirical analyses. The descriptive statistics for the independent variables were as follows. The mean values (median values) of NUM, NUM_RATIO, and NUM_ORDER were 6.8535 (5), 0.0762 (0.0694), and 6.9712 (5), respectively. In addition, the mean values (median values) of AMO, AMO_RATIO, and AMO_ORDER were 18.2314 (18.2919), 0.0725 (0.0560), and 8.1335 (7), respectively. For another independent variable, the mean value (median value) of L_NUM was 6.6705(5), and the mean values (median values) of L_NUM_RATIO and L_NUM_ORDER were 0.0745 (0.0667) and 7.0221 (5), respectively.

The descriptive statistics for the control variables included the following additional factors that affect the viability of newly listed firms. First, the mean value of public offering volume (IPO_VOL) was 24.5681, the mean value of their sales volume (SALES) was 22.6462, and the mean value of their assets taking a natural logarithm was 24.6299. In addition, the mean value of the LEV—the liability ratio of newly listed firms—was 0.3104, the mean value of the current ratio (C_RATIO) was 150.3353, and the mean value of the ROA was 0.0742. Moreover, the mean value of the AGE—calculated by taking the natural logarithm of the period from the year newly listed firms were established to the time of their listing—was 2.2409, and the mean value of operating cash flows taking a natural logarithm was 22.0942. In addition, the mean value of the discretionary accrual as a proxy for earnings management at the time of listing was 0.0583, which means that the newly listed companies generally engaged in upward earnings management. Finally, the mean value of AUDIT_DUM—a dummy variable indicating whether the auditor was equivalent to the BIG 4, a large audit corporation—was 0.5546, implying that approximately 55% of newly listed firms were audited by large audit corporations.

Panel B presents the results of the analysis of the statistical significance of the differences between the mean values of the variables. This analysis was conducted by dividing the total sample included in the empirical analysis into two groups—surviving companies and delisted companies. The results of the analysis confirmed the presence of statistically significant differences in the average values of most variables included in the empirical analysis. This is evidence of a clear distinction between surviving firms and delisted groups and proves the underlying validity of the statistically significant survival analysis results.

4.2. Kaplan–Meier Analysis

This section shows the results of the Kaplan–Meier analysis used to determine whether a statistically significant difference existed in firms’ delisting rates based on underwriters’ reputations

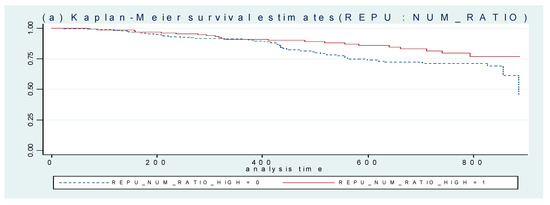

Figure 1 presents the results of the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Underwriters’ reputations were measured by dividing individual underwriters’ total number of listed successes by the total number of newly listed companies in the year preceding the listing of each newly listed company (NUM_RATIO). Figure 1a is a survival curve estimating how underwriters’ reputations affected the newly listed companies’ survival, and Figure 1b is a failure curve estimating how underwriters’ reputations affected the delisting of newly listed companies. The two graphs show that the likelihood of survival (delisting) was highest for newly listed companies employing underwriters with the highest (lowest) reputations. Moreover, the chi-square value for the difference between the two groups was 4.12, meaning the difference was statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

Figure 1.

Graph illustrating relationship between underwriters’ reputations and company delisting rates based on Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (measurement of reputation: NUM_RATIO).

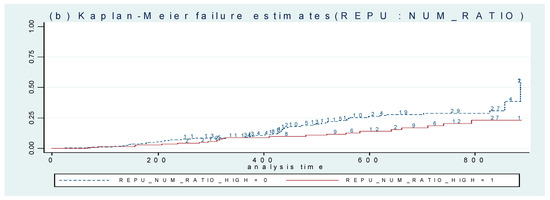

Figure 2 presents the results of the second Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Underwriters’ reputations were measured by dividing the total number of individual underwriters’ newly listed firm public offering successes by the total number of newly listed firm public offerings in the year preceding the listing of each newly listed company. Figure 2a is a survival curve estimating how underwriters’ reputations affected the survival of newly listed companies, and Figure 2b is a failure curve estimating how underwriters’ reputations affected the delisting of newly listed companies. The two graphs show that the likelihood of survival (delisting) was highest for newly listed companies employing underwriters with the highest (lowest) reputations. Moreover, the chi-square value for the difference between the two groups was 2.97, meaning the difference was statistically significant at the 10% significance level.

Figure 2.

Graph illustrating relationship between underwriters’ reputations and company delisting rates based on Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (measurement of reputation: AMO_RATIO).

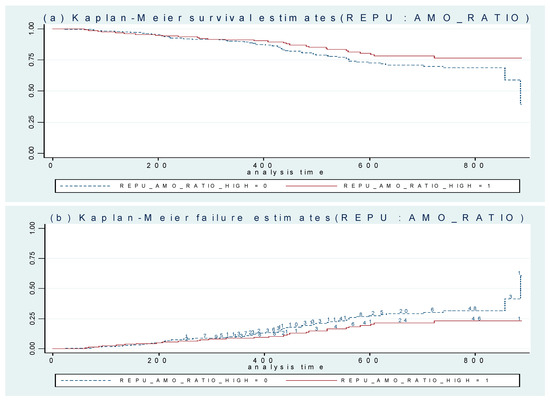

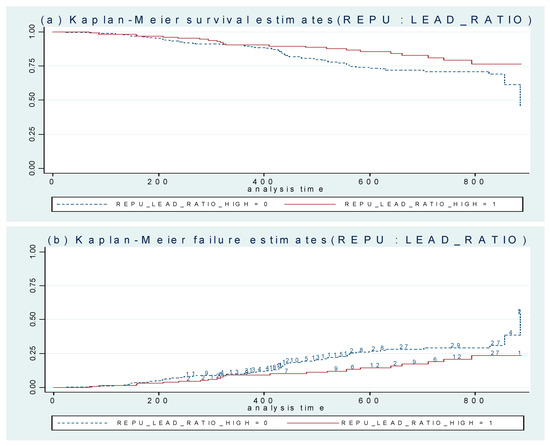

Figure 3 presents the results of the third Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Underwriters’ reputations were measured by dividing the total number of individual representative underwriters’ listed successes by the total number of newly listed companies in the year preceding the listing of each newly listed company. As with the previous analyses, Figure 3a is a survival curve estimating how underwriters’ reputations affected newly listed companies’ survival, and Figure 3b is a failure curve estimating how underwriters’ reputations affected the delisting of newly listed companies. The two graphs show that the likelihood of survival (delisting) was highest for newly listed companies employing underwriters with the highest (lowest) reputations. Moreover, the chi-square value for the difference between the two groups was 4.19, meaning the difference was statistically significant at the 5% significance level.

Figure 3.

Graph illustrating relationship between underwriters’ reputations and company delisting rates based on Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (measurement of reputation: LEAD_NUM).

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that even though different methods were used to measure reputation, the delisting risk for newly listed companies tended to be low if their underwriters had good reputations. Moreover, these analyses showed that underwriters tend to ensure that newly listed companies’ financial and operating fundamentals are healthy by faithfully accomplishing new listings for these companies. This further ensures profits through continued operations and leads companies to healthy states.

4.3. Cox Proportional Hazards Model

Based on the previous findings, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 show that the addition of variables to the model that affected the delisting rates did not change the result that underwriters with higher reputations lowered the delisting rates of newly listed companies. This is a more sophisticated analysis based on the Cox proportional hazards model.

Table 2.

Analysis of the relationship between underwriters’ reputations and companies’ delisting rates based on Cox proportional hazards model (basic measurement of evaluation: NUM).

Table 3.

Analysis of the relationship between underwriters’ reputations and companies’ delisting rates based on Cox proportional hazards model (basic measurement of evaluation: AMO).

Table 4.

Analysis of the relationship between underwriters’ reputations and companies’ delisting rates based on Cox proportional hazards model (basic measurement of evaluation: LEAD_NUM).

Table 2 (1), (2), and (3) show the empirical analysis results of the Cox proportional hazards model generated by calculating the three value measurements based on individual underwriters’ number of newly listed companies. The results of the analysis showed that two of the three reputation measurements were negatively related to the delisting rate of newly listed firms, and these relationships were statistically significant at the 1% level. This means that highly reputed underwriters perform listing process-related tasks for newly listed companies thoroughly with the aim of maintaining or improving their reputations and future business prospects. These results indicate that newly listed companies with highly reputed underwriters controlling their listing procedures tend to have superior financial and operational fundamentals, lowering the likelihood of corporate delisting.

Table 3 (1), (2), and (3) show the results of the Cox proportional hazards model generated using measurements based on individual underwriters’ total IPO volume of newly listed companies in the year before the listing. In analyzing the relationship between underwriters’ reputations and the likelihood of delisting newly listed companies, the coefficients of AMO, AMO_RATIO, and AMO_ORDER were −0.0381, −2.2721, and 0.0111, respectively. These analysis results showed a statistically significant negative correlation with delisting rates at the 1% level. These results indicate that the likelihood of delisting tends to be lower for newly listed companies with highly reputed underwriters overseeing the listing procedures because such companies have superior financial and operational fundamentals.

Table 4 (1), (2), and (3) show the results of the Cox proportional c model generated using the three-valued measure based on individual representative underwriters’ numbers of newly listed companies. Two of the three results showed statistically significant negative correlations with the delisting rate at the 1% level. The results mean that two out of three reputation measures of the relationship between the reputation of the representative underwriter and the possibility of delisting of newly listed companies showed a negative correlation. Both results also have the same meaning as those reported in Table 2 and Table 3, wherein a highly reputed underwriter thoroughly reviews the business related to the listing process of a newly listed company for the purpose of maintaining or improving their reputation while considering its future business activities. Thus, these findings indicate that newly listed companies with highly reputed underwriters overseeing listing procedures tend to have superior financial and operational fundamentals, which lowers the likelihood of corporate delisting.

If all the analysis results are combined, the delisting of newly listed companies tends to decrease statistically significantly when reputable underwriters are in charge of new listing business, which is consistent with the results of several measurements on reputation. These results also strongly support the hypothesis in terms of statistical significance, from the simplest t-test to the more complex Kaplan–Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards model with other factors. This result in relation to the fundamentals of newly listed firms and the potential delisting risk [16] and the incentives of underwriters in charge of new listing business suggests that carrying out the new listing business will improve the soundness of the company and reduce the possibility of delisting later. In practice, financial institutions with better reputations also have a positive impact on related stakeholders. A better reputation plays a role in inducing more consumers to purchase services provided by financial institutions. In addition, the trust that is formed based on the reputation of the relevant financial institution enables the financial institution to maintain its continuing business relationships with companies in partnership and to expand relationships with new companies. The results of this study can be reasonably interpreted in terms of sustainability.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined whether the reputation of underwriters significantly affects the survival period of newly listed companies. Based on existing research on underwriter reputations, their reputations were measured, and newly listed company survival periods were defined and calculated as the number of months between companies’ listings and delistings. In addition, the relationship between these two variables was analyzed.

First, underwriters’ reputations were measured by dividing them into four size-based groups. Thereafter, a Kaplan–Meier analysis of data was used regarding the groups with the highest and lowest reputations to generate a basic understanding of the impact of reputation on delisting potential. The analysis showed that the likelihood of delisting newly listed companies was low in cases involving underwriters from the highly reputable group. In addition, it confirmed that in cases involving underwriters from the less reputable group, the likelihood of delisting newly listed companies was high.

Second, based on the above analysis results, measurements of the underwriter’s reputation, which are of interest to this study, were analyzed using continuous variables instead of categorical variables. In addition, the Cox proportional hazards model was performed by adding other variables that were expected to affect the likelihood of delisting as control variables. In applying this model, even after adding other control variables to the model, the statistically significant negative relationship between underwriters’ reputation and company delisting likelihood found in the Kaplan–Meier analysis remained.

The results using two techniques of survival analyses suggested that highly reputed underwriters tend to conduct business for newly listed companies more thoroughly, as they seek to secure future business opportunities. These results also led to the conclusion that highly reputed underwriters play important roles in creating stronger foundations for newly listed companies.

Companies tend to act opportunistically to successfully complete new listings. In fact, previous studies related to newly listed companies have stated that companies that intend to be listed tend to upward manage their earnings to secure market prospects for themselves in the year immediately preceding the listings [11,12]. Reportedly, companies achieve this using not only earnings management through discretionary accruals, which tend to have relatively few side effects, but also real earnings management, which has significant side effects. Similar studies related to capital raising in corporate financing have also shown that firms can manage earnings for smooth financing ahead of paid-in capital increases, so researchers have claimed that they can predict the opportunistic behavior of a company [41,44].

In cases of new listings, the problem of information asymmetry may become more serious since the market has limited information about newly listed companies. In such cases, market participants can use other information related to newly listed companies. The reputations of underwriters, who play significant roles in overseeing the new listing process, can not only serve to decrease information asymmetry between internal and external related parties but also act as an important source of information for market participants [3,31,32,34,35].

As financial institutions, investment banks generally tend to maintain long-term business relationships with related companies. This is because they maintain the long-term relationships established through new listings to reduce information costs, such as exploration and transaction costs, rather than short-term ones. As an underwriter, therefore, the investment bank may have an incentive to continue its business relationship with customer companies by successfully performing its work and consistently gaining a good reputation as newly listed companies maintain good performance in the future. In addition, if a newly listed company’s performance is judged to be reflected in its reputation, or if it wishes to avoid the possibility of subsequent legal problems damaging its reputation, it will serve to strengthen the financial reporting of not only the financial foundation but also the newly listed company. This also applies to companies wanting to be listed, and based on this, it can be assumed that the underwriter who plays a key role in the IPO process will continue its business relationship with customers by gaining a good reputation with successful new listings. Therefore, it is assumed that underwriters affect newly listed companies in a way that increases their financial health, which ultimately serves to lower the risk of delisting newly listed companies.

This study showed that the higher the reputation of the underwriters, the lower the delisting rate of newly listed companies, which means the higher the sustainability of the newly listed companies. These findings indicate that newly listed companies with highly reputed underwriters have relatively better business and financial status due to underwriters’ incentives to maintain their reputations. This is one of the important contributions of the study, because few studies have directly hypothesized on and analyzed the relationship between underwriters’ reputations and the viability of newly listed firms. If an analysis based on data from other countries proves that the results are generalizable rather than just limited to South Korea, it would be meaningful as well.

Moreover, this study contributed to the study of reputation by showing empirical evidence that the stockholder responsible for the newly listed business performs a role of certifying the operation and financial soundness of the newly listed firm and, ultimately, its viability in the capital market. Potential investors in the capital market may hesitate to make timely investment decisions due to insufficient information if they want to invest in newly listed firms. In addition, there is a tendency for active investment not to be made due to the possibility of misinformed investment results caused by a lack of information. Therefore, this study can contribute to the continued development of the capital market by helping to ensure that investors’ decisions can be made actively.

In addition, this study is differentiated from other business studies in that it has produced meaningful results using survival analysis, which has not been widely used in conventional business studies. Survival analysis is an analytical method generally used in biology or medical research to verify whether or the extent to which the survival rate of subjects varies with a treatment. Therefore, few business studies use survival analysis. However, this study replaced the treatment with the reputation of the underwriters in charge of new listing business and replaced the survival and duration of the subject with the survival and duration of newly listed companies. This is different from prior studies, as it extends the applicability of existing survival analysis. Whether a newly listed firm is delisted and the period of listing can be analyzed by OLS regression, logit analysis, and probit analysis, which are generally widely used in business studies, but it is believed that survival analysis offers a more sophisticated method of analysis. Therefore, this study can be differentiated from existing management studies in that it has produced significant results through more sophisticated analyses.

Despite the above significance and academic, legal, and policy implications, the study has the following limitations: Based on existing reputation-related research and using the newly listed data available in Korea, this study measured the underwriter’s reputation in a variety of ways, but the problem is that the measures only used quantitative indicators. If reputation can be measured by qualitatively evaluating the achievement and successful maintenance of a new listing in the future or by reflecting both quantitative and qualitative indicators, indicators that reflect more diverse aspects are considered to be available for future research on reputation. Additionally, it is expected that if this research is expanded and developed using new reputation-related indicators, more in-depth discussions can be held on the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the impact of future underwriters’ reputation-related causes on their responsibilities and roles within the capital market. Furthermore, this is expected to be the basis for a richer understanding of the actions and motivations of capital market participants as well as the development of research related to the capital market, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the capital market.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, R.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Tsai, S.B. IPO Underpricing After the 2008 Financial Crisis: A Study of the Chinese Stock Markets. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, C.S.; Gatchev, V.A.; Spindt, P.A. Wanna dance? How firms and underwriters choose each other. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 2437–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.B.; Manaster, S. Initial public offerings and underwriter reputation. J. Financ. 1990, 45, 1045–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megginson, W.L.; Weiss, K.A. Venture capitalist certification in initial public offerings. J. Financ. 1991, 46, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Woo, J.J.; Ryoo, H.S. The Financial Features of Venture Businesses Listed on KOSDAQ. Adv. S. E. Innov. Res. 2000, 3, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.W.; Lee, K.H.; Nam, K.P. The Grandstanding of Venture Capitalist and the Aftermarket Performance of IPOs. Korean Manag. Rev. 2002, 31, 1631–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B.S. The Impact of Underwriter’s Reputation on the KOSDAQ’s IPOs. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2003, 16, 105–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.G.; Kim, C.G. A Study on the Earnings Management of KOSDAQ IPO Firms. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2005, 18, 2681–2700. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. The Hot and Cold Market Impacts on Underpricing of Certification, Reputation and Conflicts of Interest in Venture Capital Backed Korean IPOs. Adv. S. E. Innov. Res. 2009, 12, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.S.; Ryu, D. Venture Capitalist Certification in Initial Public Offerings: The Case of KOSDAQ Market. Korean Corp. Manag. Rev. 2010, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.; Masulis, R.W. Do more reputable financial institutions reduce earnings management by IPO issuers? J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 982–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kang, P.; Kim, N. The Impact of Underwriter’s Reputation on IPO Firm’s Earnings Management. Korean Acad. Soc. Account. 2015, 20, 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lizińska, J.; Czapiewski, L. Towards Economic Corporate Sustainability in Reporting: What Does Earnings Management around Equity Offerings Mean for Long-Term Performance? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R. Regression models and life-table (with discussion). J. R. Stat. Soc. 1972, 34, 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lockett, A.; Moon, J.; Visser, W. Corporate social responsibility in management research: Focus, nature, salience and sources of influence. J. Mgt. Stud. 2006, 43, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, P.; Marques, R. Influence of regulation on the productivity of waste utilities. What can we learn with the Portuguese experience? Waste Mgt. 2012, 32, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, R. Earnings management in an overlapping generations model. J. Account. Res. 1988, 26, 195–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, S.; Welch, I.; Wong, T. Earnings management and the long-run market performance of initial public offerings. J. Financ. 1998, 53, 1935–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, S.; Wong, T.; Rao, G. Are accruals during initial public offerings opportunistic? Rev. Account. Stud. 1998, 3, 175–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affleck-Graves, J.; Callahan, C.M.; Chipalkatti, N. Earnings predictability, information asymmetry, and market liquidity. J. Account. Res. 2002, 40, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J. Earnings Management and Delisting Risk of Initial Public Offerings; Working Paper; Simon School, University of Rochester, Research Paper Series; 2006; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=641021 (accessed on 8 May 2019).

- Krishnan, C.N.V.; Masulis, R.W.; Ivanov, V.I.; Singh, A.K. Venture capital reputation and post-IPO performance, and corporate governance. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2011, 46, 1295–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.B.; Muscarella, C.J.; Peavy, J.W., III; Vetsuypens, M.R. The role of venture capital in the creation of public companies: Evidence from the going-public process. J. Financ. Econ. 1990, 27, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Nabar, P. Economic implications of imperfect quality certification. Econ. Lett. 1991, 37, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, S.; Trueman, B. Information Quality and the Valuation of New Issues. J. Account. Econ. 1986, 8, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemmanur, T.; Fulghieri, P. Investment Bank Reputation, Information Production, and Financial Intermediation. J. Financ. 1994, 49, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Ljungqvist, A. Underpricing and Entreprenurial Wealth Losses in IPOs: Theory and Evidence. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2001, 14, 433–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, L.; Ljungqvist, A.; Wilhelm, W.; Yu, X. Evidence of Information Spillovers in the Production of Investment Banking Services. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 577–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, A.; Marston, F.; Wilhelm, W. Competing for Securities Underwriting Mandates: Banking Relationships and Analyst Recommendations. J. Financ. 2006, 61, 301–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, R.; Ritter, J.R. Investment banking, reputation and the underpricing of initial public offerings. J. Financ. Econ. 1986, 15, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J.R.; Smith, R.L. Capital raising, underwriting and the certification hypothesis. J. Financ. Econ. 1986, 15, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.B.; Dark, F.H.; Singh, A.K. Underwriter Reputation, Initial Returns, and the Long-Run Performance of IPO Stocks. J. Financ. 1998, 53, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C.G. Factors affecting investment bank initial public offering market share. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 55, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.H. Investment bank reputation and the price and quality of underwriting services. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 2729–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Kim, M. Initial Public Offerings and Earnings Management. Korean Account. Rev. 1997, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.S. Firm-Bank Relationship and The Corporate Governance Role of Banks: Evidence from Borrower’s Accounting Conservatism; Working Paper; California State University: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.S.; Kwak, Y.M.; Baek, J.H. Earnings Management around Initial Public Offerings in KOSDAQ Market Associated with Managerial Opportunism. Korean Account. Rev. 2010, 35, 37–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ragan, S. Earnings management and the performance of seasoned equity offerings. J. Financ. Econ. 1998, 50, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Du Charme, L.L.; Malatesta, P.H.; Sefcik, S.E. Earnings management, stock issues, and shareholder lawsuits. J. Financ. Econ. 2004, 71, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Masulis, R.W. Seasoned equity offerings: Quality of accounting information and expected flotation costs. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 92, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.P.; Park, S.W.; Lee, K.H. The Long-term Performance of Venture Capital-Backed IPOs. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2003, 37, 687–711. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.S.; Lee, H.I.; Choi, S.H. Earnings Management of Initial Public Offerings: Evidence from Venture Capital-Backed Firms. Korean Account. Rev. 2014, 39, 179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, N.; Marques, R. Scorecards for sustainable local governments. Cities 2014, 39, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, M.S. Underwriter choice and earnings management: Evidence from seasoned equity offerings. Rev. Account. Stud. 2007, 12, 23–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensler, D.A.; Rutherford, R.C.; Springer, T.M. The survival of initial public offerings in the aftermarket. J. Financ. Res. 1997, 20, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Clarke, J.; Cooney, J. The impact of reputation on analysts’ conflicts of interest. Hot versus cold markets. J. Bank. Financ. 2012, 36, 2190–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.M.; Choi, J.S. Survival Analysis of IPO Firms Engaging in Earnings Management: Evidence from KOSDAQ Market. Korean Account. J. 2011, 20, 231–263. [Google Scholar]

- Alhadab, M.; Clacherm, I.; Keasey, K. Real and accrual earnings management and IPO failure risk. Account. Bus. Res. 2015, 45, 55–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Financial Information Asymmetry and Delisting of IPO Firms. J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2018, 20, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Gompers, P. Grandstanding in the venture capital industry. J. Financ. Econ. 1996, 42, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Woo, J.J. An Empirical Analysis of the Role of Venture Capitalists in KOSDAQ IPOs market. Korean Assoc. Small Bus. Stud. 2002, 5, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B.S.; Lee, K.H. The Impact of Venture Capitalist’s Reputation on KOSDAQ IPOs. Asia Pac. J. Small Bus. 2003, 25, 239–269. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R.K.; Krigman, L.; Womack, K.L. Strategic IPO Underpricing, Information Momentum, and Lockup Expiration Selling. J. Financ. Econ. 2002, 66, 105–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Hwang, K. Impact of Underwriter reputation on the accounting conservatism of the IPO firm: South Korean cases. Int. J. Econ. Pol. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 11, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. Taking A Private Company Public; Scott Printing Corporation: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, A. Just like film stars Wall Streeters battle to get top billing. Wall Street Journal, 15 January 1986; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mata, J.; Portugal, P.; Guimaraes, P. The Survival of New Plants: Start-up Conditions and Post-entry Evolution. Int. J. Ind. Org. 1995, 13, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. Earnings management during import relief investigation. J. Account. Res. 1991, 29, 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).