Enhancing Employee Creativity for A Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Perceived Human Resource Management Practices and Trust in Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

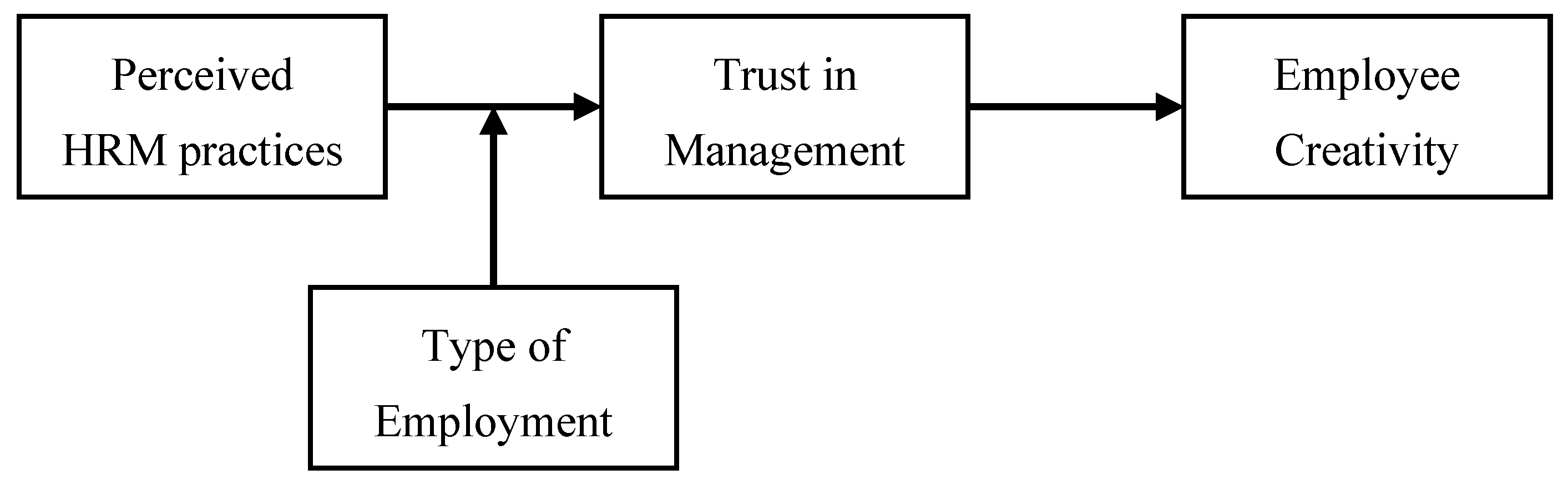

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Perceived HRM Practices and Employees’ Trust in Management

2.2. Trust in Management and Employees’ Creativity

2.3. The Mediating Impact of Trust in Management on the Relation between Perceived HRM Practices and Employees’ Creativity

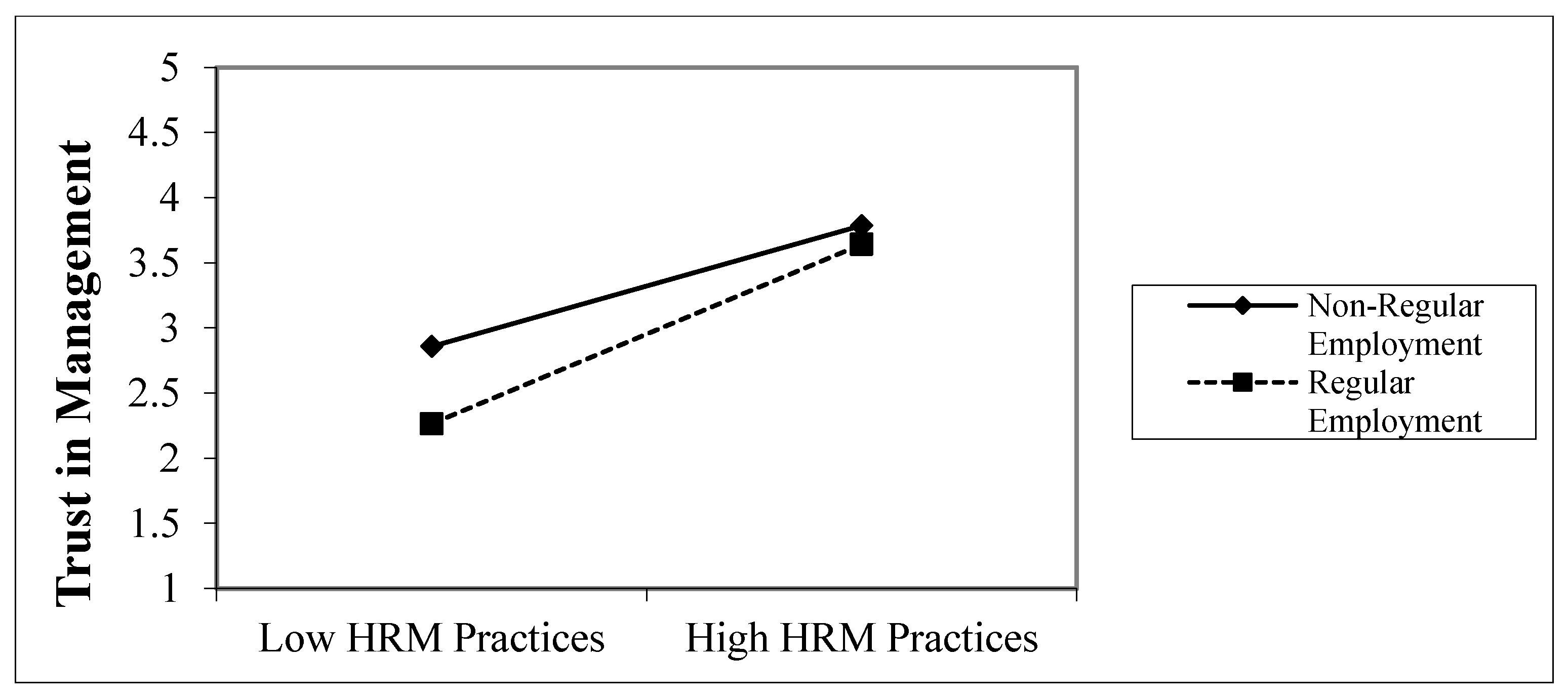

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Type of Employment

2.5. The Moderated Mediation

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Perceived HRM Practices

3.2.2. Trust in Management

3.2.3. Type of Employment

3.2.4. Employees’ Creativity

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analyses

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.; Truss, C. The link between perceived HRM practices, performance and well-being: The moderating effect of trust in the employer. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.D.; Truss, C.; Soane, E.C. The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E. Employees’ overall perception of HRM effectiveness. Hum. Relat. 2005, 58, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J. HR practices, organizational climate and employee outcomes: Evaluating social exchange relationships in local government. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1627–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M.; Aust, I. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Perception: The influence of Manager and Line Managers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The Impact of High-Performance Human Resource Practices on Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piening, E.P.; Baluch, A.M.; Ridder, H.-G. Mind the intended-implemented gap: Understanding employees’ perceptions of HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chang, S.; Cheung, S.-Y. High performance work system and collective OCB: A collective social exchange perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2010, 20, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.D.; Dineen, B.R.; Fang, R.; Vellella, R.F. Employee-organization exchange relationships, HRM practices, and quit rates of good and poor performers. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1016–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafrir, S.S.; Harel, T.L.G.H.; Baruch, Y.; Dolan, S.L. The consequences of emerging HRM practices for employees’ trust in their managers. Pers. Rev. 2004, 33, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management: The workers’ verdict. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 1999, 9, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorza, U.; Harris, C.; Aritzeta, A.; Balluerka, N. The effect of management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems on employees’ discretionary behaviour. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.-C.; Farh, J.-L. Employee Learning Orientation, Transformational Leadership, and Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Creative Self-Efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S. Does HRM facilitate employee creativity and organizational innovation? A study of Chinese firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 4025–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; De Dreu, C.K.; Nijstad, B.A. The routinization of innovation research: A constructively critical review of the state-of-the-science. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Shalley, C.E. Research on employee creativity: A critical review and directions for future research. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; pp. 165–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.L.; Hall, B. ‘J’ Facilitating talk about new ideas: The role of personal relationships in organizational innovation. Commun. Monogr. 1991, 58, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Sutton, R.I. The Knowing-Doing Gap; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sethia, N.K. The Shaping of Creativity in Organizations. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 1989, pp. 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewett, T. Linking intrinsic motivation, risk taking, and employee creativity in an R&D environment. RD Manag. 2007, 37, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E. Social yet creative: The role of social relationships in facilitating individual creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, R.W.; Sawyer, J.E.; Griffin, R.W. Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidault, F.; Castello, A. Trust and creativity: Understanding the role of trust in creativity-oriented joint developments. RD Manag. 2009, 39, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, R.D.; Ilter, S.S.; Berman, J.J. A Multi-Dimensional Study of Trust in Organizations. J. Manag. Issues 1998, 10, 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D.; Gustafson, S.B. Creativity syndrome: Integration, application, and innovation. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoorman, F.D.; Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust: Past, Present, and Future. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of Innovative Behavior: A Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M.; Graen, G.B. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 591–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Vela-Jiménez, M.-J.; Pérez-Pérez, M.; De-Luis-Carnicer, P. The Dynamics of Labour Flexibility: Relationships between Employment Type and Innovativeness. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 715–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M. Readings in HRM and Sustainability; Tilde University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, A.; Hill, M.; Gollan, P. The sustainability debate. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Gould-Williams, J. The importance of HR practices and workplace trust in achieving superior performance: A study of public-sector organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H.; Näswall, K. ‘Objective’ vs ‘subjective’ job insecurity: Consequences of temporary work for job satisfaction and organizational commitment in four European countries. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2003, 24, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, S.A.; Dean, J.W. Integrated Manufacturing and Human Resource Management: A Human Capital Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 467–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhala, M.; Ahteela, R. The effect of HRM practices on impersonal organizational trust. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 869–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Wall, T. New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfilment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1980, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Tierney, P.; Kung-McIntyre, K. Employee Creativity in Taiwan: An Application of Role Identity Theory. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chatterjee, S.; Hadi, A.S. Regression Analysis by Example; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 607, ISBN 9780471746966. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M. Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafferkey, K.; Dundon, T. Explaining the black box: HPWS and organisational climate. Pers. Rev. Farnb. 2015, 44, 666–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M.A. The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.R.; Burke, M.J.; George, J.M.; Webster, J.; Robinson, B.S. Should Negative Affectivity Remain an Unmeasured Variable in the Study of Job Stress? J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorman, R.H.; Podsakoff, P.M. A meta-analytic review and empirical test of the potential confounding effects of social desireablility response sets in organizational behavior research. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1992, 65, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Viswesvaran, C.; Reiss, A.D. Role of social desirability in personality testing for personnel selection: The red herring. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method variance as an artifact in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Myth or significant problem? J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Chen, P.Y.; O’Connell, B.J. A longitudinal study of relations between job stressors and job strains while controlling for prior negative affectivity and strains. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Fctr 1 | Fctr 2 | Fctr 3 | Fctr 4 | Fctr 5 | Fctr 6 | Fctr 7 | Fctr 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Security | ||||||||

| Employees in this job can expect to stay in the organizations for as long as they wish. | .797 | |||||||

| Job security is almost guaranteed to employees in this job. | .724 | |||||||

| If our company were facing economic problems, employees in this job would be the last to be cut. | .812 | |||||||

| Selective Hiring | ||||||||

| Our company is trying to recruit competent people. | .649 | |||||||

| Our company invests a lot of time to recruit people. | .805 | |||||||

| Our company invests a lot of man-hours to recruit people. | .846 | |||||||

| Our company invests a lot of money to recruit people. | .780 | |||||||

| Education and Training | ||||||||

| Extensive training programs are provided for individuals in this job. | .826 | |||||||

| Employees in this job will normally go through training programs every few years. | .789 | |||||||

| There are formal training programs to teach new hires the skills they need to perform their jobs. | .639 | |||||||

| Fair Performance Appraisal | ||||||||

| Performance is evaluated by accurate means. | .803 | |||||||

| Performance is evaluated by objective means. | .804 | |||||||

| Feedback about performance is provided frequently. | .639 | |||||||

| In determining compensation, the individual’s contribution is emphasized more than his or her position. | .584 | |||||||

| Participation in Decision Making | ||||||||

| Employees in this job are allowed to make many decisions. | .780 | |||||||

| Employees are encouraged to suggest improvements in the way we work. | .806 | |||||||

| Superiors keep open communications with employee in this job. | .848 | |||||||

| Employees are often asked by their managers to participate in the decision-making process. | .729 | |||||||

| Reduction of Status Differences | ||||||||

| Our company is trying to reduce the wage differential between employment types. | .831 | |||||||

| Our company is trying to transition temporary employees into permanent roles. | .840 | |||||||

| Our company is trying to reduce the benefits differential between employment types. | .905 | |||||||

| Our company is trying to reduce the difference in working conditions between employment types. | .903 | |||||||

| Retirement Management | ||||||||

| Our company has an effective retirement management program for employee well-being after retirement. | .683 | |||||||

| Our company supports employees to create a new life after retirement. | .836 | |||||||

| Our company helps employees find a new job. | .860 | |||||||

| Our company has a support program to help retirees start businesses. | .844 | |||||||

| Benefits Package | ||||||||

| Relative to that of other companies, I am satisfied with the level of benefit package. | .850 | |||||||

| I am satisfied with our company’s benefit package over the last few years. | .856 | |||||||

| Generally, I am satisfied with our company’s benefit package. | .848 | |||||||

| Variance after Rotation | 3.775 | 3.192 | 3.127 | 3.112 | 3.105 | 2.655 | 2.191 | 2.082 |

| Percent of Explained Variance | 13.02 | 11.01 | 10.78 | 10.73 | 10.71 | 9.16 | 7.56 | 7.18 |

| Cumulative Percent of Explained Variance | 13.02 | 24.03 | 34.81 | 45.54 | 56.25 | 65.41 | 72.97 | 80.15 |

| Variables | Item | Un. St. Coeff. | St. Coeff. | S.E. | C.R. | p | Construct Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Performance Work System | ES | 1.00 | .47 | |||||

| SH | 2.06 | .75 | .38 | 5.37 | 0.00 | |||

| ET | 1.97 | .71 | .37 | 5.36 | 0.00 | |||

| FPA | 2.61 | .79 | .49 | 5.38 | 0.00 | |||

| PDM | 2.56 | .78 | .46 | 5.56 | 0.00 | |||

| RSD | 1.77 | .55 | .34 | 5.13 | 0.00 | |||

| RM | 1.25 | .62 | .26 | 4.74 | 0.00 | |||

| BP | 1.87 | .59 | .37 | 4.99 | 0.00 | |||

| Employment Security (ES) | ES1 | 1.00 | .53 | .777 | .555 | |||

| ES2 | 1.47 | .99 | .19 | 7.86 | 0.00 | |||

| ES3 | 0.94 | .64 | .10 | 9.26 | 0.00 | |||

| Selective Hiring (SH) | SH1 | 1.00 | .75 | .909 | .716 | |||

| SH2 | 1.11 | .85 | .07 | 15.35 | 0.00 | |||

| SH3 | 1.24 | .93 | .09 | 13.97 | 0.00 | |||

| SH4 | 1.10 | .84 | .08 | 13.51 | .00 | |||

| Education And Training (ET) | ET1 | 1.00 | .87 | .837 | .636 | |||

| ET2 | 1.06 | .86 | .07 | 16.08 | 0.00 | |||

| ET3 | 0.91 | .64 | .08 | 11.43 | 0.00 | |||

| Fair Performance Appraisal (FPA) | FPA1 | 1.00 | .94 | .896 | .689 | |||

| FPA2 | 1.03 | .97 | .03 | 32.57 | 0.00 | |||

| FPA3 | 0.73 | .71 | .05 | 15.70 | 0.00 | |||

| FPA4 | 0.76 | .65 | .06 | 13.49 | 0.00 | |||

| Participation In Decision making (PDM) | RM1 | 1.00 | .92 | .906 | .708 | |||

| RM2 | 0.95 | .85 | .05 | 19.57 | 0.00 | |||

| RM3 | 0.85 | .78 | .05 | 16.50 | 0.00 | |||

| RM4 | 0.85 | .82 | .05 | 18.33 | 0.00 | |||

| Reduction Of Status Difference (RSD) | RSD1 | 1.00 | .80 | .940 | .799 | |||

| RSD2 | 1.05 | .81 | .05 | 20.95 | 0.00 | |||

| RSD3 | 1.27 | .97 | .06 | 21.15 | 0.00 | |||

| RSD4 | 1.29 | .97 | .06 | 21.14 | 0.00 | |||

| Retirement Management (RM) | RM1 | 1.00 | .63 | .890 | .674 | |||

| RM2 | 1.19 | .78 | .09 | 12.84 | 0.00 | |||

| RM3 | 1.40 | .91 | .12 | 12.17 | 0.00 | |||

| RM4 | 1.43 | .93 | .12 | 12.30 | 0.00 | |||

| Benefits Package (BP) | BP1 | 1.00 | .90 | .948 | .859 | |||

| BP2 | 1.08 | .93 | .04 | 25.47 | 0.00 | |||

| BP3 | 1.11 | .95 | .04 | 27.17 | 0.00 | |||

| Trust in Management (TM) | TM1 | 1.00 | .80 | .910 | .716 | |||

| TM2 | 1.08 | .83 | .07 | 15.72 | 0.00 | |||

| TM3 | 1.15 | .87 | .07 | 15.80 | 0.00 | |||

| TM4 | 1.05 | .88 | .07 | 15.16 | 0.00 | |||

| Creativity (CR) | CR1 | 1.00 | .89 | .860 | .613 | |||

| CR2 | 1.04 | .91 | .06 | 18.34 | 0.00 | |||

| CR3 | 0.77 | .70 | .06 | 13.45 | 0.00 | |||

| CR4 | 0.71 | .58 | .07 | 10.57 | 0.00 | |||

| Goodness-of-Fit Indices | χ2(d.f.) = 1086.96 (598), χ2/d.f = 1.818 (p < 0.001) GFI = 0.832, CFI = 0.945, IFI = 0.946, TLI = 0.939, RMSEA = 0.054 | |||||||

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.27 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| 2. Age | 35.56 | 5.78 | −0.31 ** | ||||||||

| 3. Tenure | 6.24 | 4.87 | −0.12 * | 0.73 ** | |||||||

| 4. Master’s degree | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.03 | ||||||

| 5. Doctorate degree | 0.19 | 0.39 | −0.11 | 0.45 ** | 0.10 | −0.54 * | |||||

| 6. Type of employment | 0.75 | 0.44 | −0.10 | 0.23 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.12 | 0.01 | ||||

| 7. Perceived HRM practices | 2.98 | 0.57 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.06 | (.94) | ||

| 8. Trust in management | 2.84 | 0.83 | −0.01 | −0.13 * | −0.20 ** | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.16 ** | 0.73 ** | (.92) | |

| 9. Creativity | 3.33 | 0.61 | −0.09 | 0.13 * | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.18 ** | −0.05 | 0.25 ** | 0.29 ** | (.87) |

| Trust in Management | Creativity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

| Constant | 2.996 ** (.539) | −.119 (.410) | .851 (.448) | 2.913 ** (.394) | 2.257 ** (.398) | 2.139 ** (.424) | 2.161 (.418) |

| Gender | −.043 | .035 | −.029 | −.057 | −.048 | −.038 | −.045 |

| (.117) | (.080) | (.077) | (.085) | (.082) | (.083) | (.082) | |

| Age | .006 | −.002 | −.004 | .014 | .013 | .013 | .013 |

| (.016) | (.011) | (.010) | (.011) | (.011) | (.011) | (.011) | |

| Master’s degree | −.071 | −.041 | .027 | .030 | .046 | .037 | .044 |

| (.118) | (.081) | (.078) | (.086) | (.082) | (.084) | (.083) | |

| Doctorate degree | −.055 | .011 | .082 | .205 | .217 | .222 | .220 |

| (.179) | (.123) | (.118) | (.131) | (.125) | (.127) | (.125) | |

| Tenure | −.039 | −.020 | −.005 | −.013 | −.005 | −.008 | −.004 |

| (.016) | (.011) | (.011) | (.011) | (.113) | (.011) | (.011) | |

| Type of employment | −1.537 ** | ||||||

| (.371) | |||||||

| Perceived HRM practices | 1.051 ** (0.059) | .821 ** (.099) | .261 ** (.061) | .066 (.088) | |||

| Perceived HRM practices × Type of employment | .394 ** (.122) | ||||||

| Trust in management | .219 ** (.042) | .186 ** (.061) | |||||

| F | 2.60 * | 56.81 ** | 51.00 ** | 2.43 * | 6.77 ** | 5.16 ** | 5.88 ** |

| R2 | .045 | .551 | .597 | .042 | .128 | .100 | .129 |

| Adj. R2 | .027 | .541 | .585 | .025 | .109 | .081 | .107 |

| Conditional Indirect Effects of Two Types of Employment | Boot Indirect Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent employment | .142 | .055 | .043 | .267 |

| Temporary employment | .209 | .076 | .062 | .363 |

| Mediator | Index | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in management | .067 | .031 | .018 | .143 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Moon, S. Enhancing Employee Creativity for A Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Perceived Human Resource Management Practices and Trust in Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082305

Lee J, Kim S, Lee J, Moon S. Enhancing Employee Creativity for A Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Perceived Human Resource Management Practices and Trust in Management. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082305

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Juil, Sangsoon Kim, Jiman Lee, and Sungok Moon. 2019. "Enhancing Employee Creativity for A Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Perceived Human Resource Management Practices and Trust in Management" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082305

APA StyleLee, J., Kim, S., Lee, J., & Moon, S. (2019). Enhancing Employee Creativity for A Sustainable Competitive Advantage through Perceived Human Resource Management Practices and Trust in Management. Sustainability, 11(8), 2305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082305