Acquiescence or Resistance: Group Norms and Self-Interest Motivation in Unethical Consumer Behaviour

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Reference Group and Unethical Consumer Behaviour

2.2. Self-Interest Motivation and Unethical Consumption Behaviour

2.3. The Mediating Role of Moral Disengagement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Sample

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Direct Effect and Mediating Effect Analyses

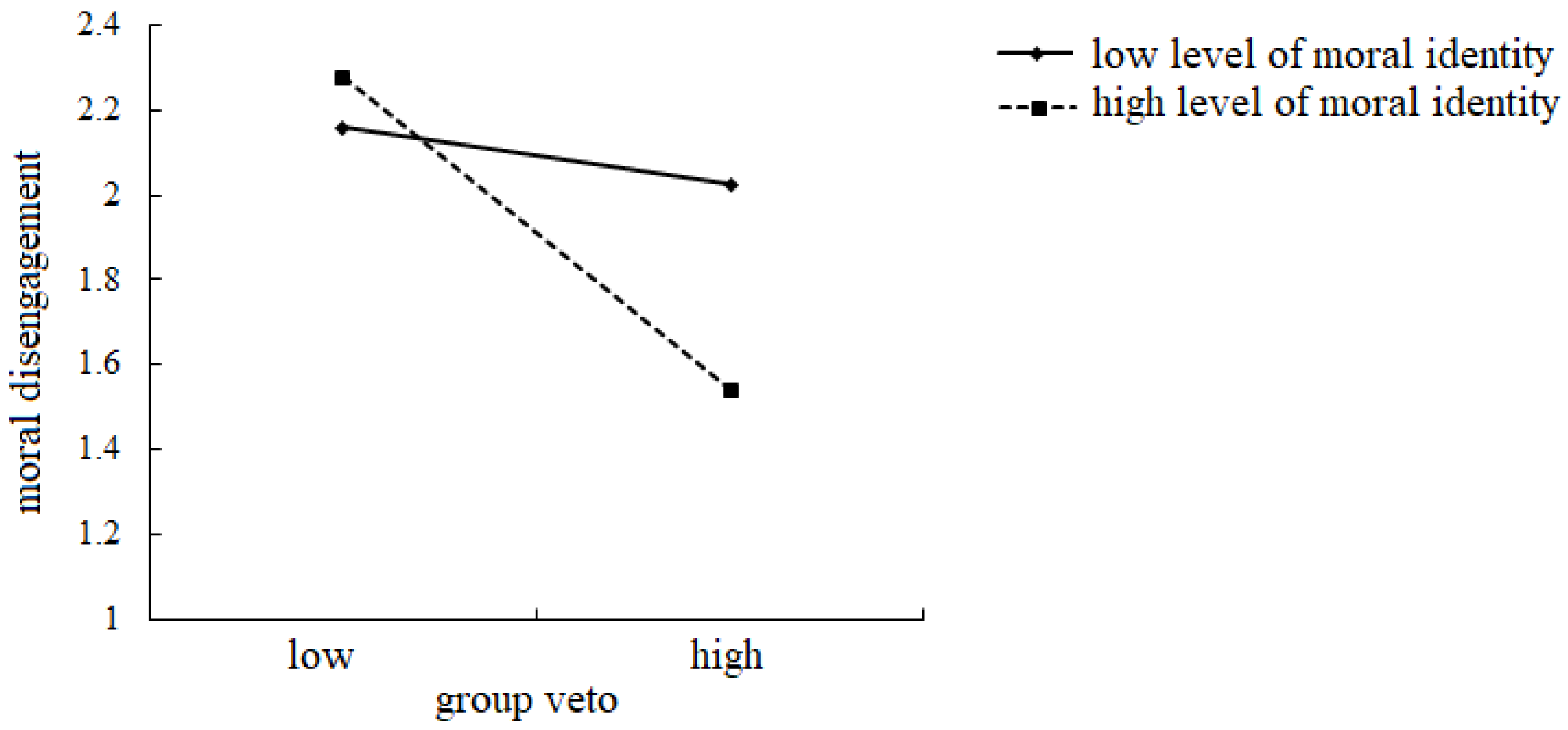

4.2. Moderating Effect of Moral Identity

4.3. Moderated Mediation Effect of Moral Identity

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Group recognition (Park and Lessig, 1977; Bearden and Etzel, 1982) [15,16] |

| 1. Some of my purchasing behaviour can largely reflect my social status. |

| 2. Some of my purchasing behaviour can show others what I am or would like to be. |

| 3. Getting approval from others is important for me to make certain purchases. |

| 4. Some of my purchasing behaviour can enhance my image in the mind of others. |

| 5. By buying the same product or brand as a particular group, I get a sense of belonging. |

| 6. By buying the same products or brands as a particular group, our relationship will be more harmonious. |

| Group veto (Park and Lessig, 1977; Bearden and Etzel, 1982) [15,16] |

| 1. If I can predict that my purchasing behaviour will be rejected by the group, I will make timely adjustments. |

| 2. If the group does not expect me to make the purchase, I will stop doing so. |

| 3. My choice of buying behaviour should take into account other people’s reactions. |

| 4. If such purchasing is not conducive to enhancing my image in other people’s minds, I will stop doing so. |

| Altruism motivation (Berkowitz and Lutterman, 1968; Rammstedt and John, 2007) [72,73] |

| 1. I am a dependable person. |

| 2. I am a self-disciplined person. |

| 3. Everyone has a responsibility to do his best to finish the work. |

| 4. When I do not finish the work I promised, I felt terrible. |

| 5. Everyone should contribute to his hometown or country. |

| Egoism motivation (Jakobwitz and Egan, 2006) [71] |

| 1. Never tell someone the real reason why you do something unless it is good for you. |

| 2. The best way to get along with someone is to say what they like to hear. |

| 3. In dealing with others, it is best to assume that everyone has a dark side. |

| 4. If a person believes in another person completely, then he is asking for trouble. |

| 5. It is hard to succeed without taking shortcuts. |

| Moral disengagement (Moore et al., 2012) [53] |

| 1. It is unavoidable to use force to protect my interests. |

| 2. It does not matter to spread rumours to protect the people I care about. |

| 3. Considering that people often try to disguise themselves, it is not a mistake to exaggerate my qualifications. |

| 4. If a person makes a mistake because all his friends do it, he should not be blamed. |

| 5. If something is allowed by authority figures, then I should not take responsibility. |

| 6. It is no big deal to attribute other people’s ideas to myself. |

| 7. For those who do not feel hurt, we can be cruel. |

| 8. Usually the person who is hurt is his own incompetence and cannot avoid injury. |

| Moral identity (Aquino and Reed, 2002) [64] |

| 1. If I were a compassionate, fair and friendly person, I would feel good. |

| 2. Being a compassionate, fair and friendly person is part of self-pursuit. |

| 3. I am proud to be a compassionate, fair and friendly person. |

| 4. I am eager to be a compassionate, fair and friendly person. |

| 5. It is important for me to be a compassionate, fair and friendly person. |

| Unethical behavioural intention (Bhattacherjee, 2001) [74] |

| 1. I am willing to use pirated software. |

| 2. I intend to continue using pirated software. |

| 3. I would like to continue using pirated software if possible. |

Appendix B. Measurement Model

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group recognition | GA1 | 0.820 | 0.939 | 0.952 | 0.767 |

| GA2 | 0.877 | ||||

| GA3 | 0.871 | ||||

| GA4 | 0.923 | ||||

| GA5 | 0.883 | ||||

| GA6 | 0.876 | ||||

| Group veto | GD1 | 0.886 | 0.827 | 0.888 | 0.668 |

| GD2 | 0.863 | ||||

| GD3 | 0.627 | ||||

| GD4 | 0.865 | ||||

| Altruism motivation | AM1 | 0.814 | 0.883 | 0.916 | 0.686 |

| AM2 | 0.709 | ||||

| AM3 | 0.883 | ||||

| AM4 | 0.876 | ||||

| AM5 | 0.846 | ||||

| Egoism motivation | EM1 | 0.843 | 0.891 | 0.921 | 0.700 |

| EM2 | 0.896 | ||||

| EM3 | 0.830 | ||||

| EM4 | 0.883 | ||||

| EM5 | 0.721 | ||||

| Moral disengagement | MD1 | 0.841 | 0.916 | 0.944 | 0.682 |

| MD2 | 0.846 | ||||

| MD3 | 0.869 | ||||

| MD4 | 0.859 | ||||

| MD5 | 0.912 | ||||

| MD6 | 0.827 | ||||

| MD7 | 0.605 | ||||

| MD8 | 0.813 | ||||

| Moral identity | MI1 | 0.849 | 0.931 | 0.949 | 0.790 |

| MI2 | 0.930 | ||||

| MI3 | 0.932 | ||||

| MI4 | 0.921 | ||||

| MI5 | 0.805 | ||||

| Unethical behavioural intention | UBI1 | 0.968 | 0.969 | 0.980 | 0.942 |

| UBI2 | 0.983 | ||||

| UBI3 | 0.860 |

References

- Vitell, S.J.; Muncy, J. Consumer ethics: An empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgments of the final consumer. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X. Stress and unethical consumer attitudes: The mediating role of construal level and materialism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U. When Ethical Transgressions of Customers Have Beneficial Long-Term Effects in Retailing: An Empirical Investigation. J Retail. 2017, 93, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, J.M.; Huang, S. Examining Chinese Consumers’ Knowledge, Face-Saving, Materialistic, and Ethical Values with Attitudes of Counterfeit Goods. In Social Responsibility; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, R.M.M.I.; Fernando, M. The Relationships of Empathy, Moral Identity and Cynicism with Consumers’ Ethical Beliefs: The Mediating Role of Moral Disengagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Sparks, J.R. Predictors, consequence, and measurement of ethical judgments: Review and meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gentina, E.; Shrum, L.J.; Lowrey, T.M.; Vitell, S.J.; Rose, G. An Integrative Model of the Influence of Parental and Peer Support on Consumer Ethical Beliefs: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem, Power, and Materialism. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 1173–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Tian, Z. Relationship between consumer ethics and social rewards-punishments in Mainland China. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2009, 3, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z. “Monkey See, Monkey Do?”: The Effect of Construal Level on Consumers’ Reactions to Others’ Unethical Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Mourali, M. Effect of peer influence on unauthorized music downloading and sharing: The moderating role of self-construal. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Kim, H. Are Ethical Consumers Happy? Effects of Ethical Consumers’ Motivations Based on Empathy Versus Self-orientation on Their Happiness. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, M. New Insights into Socially Responsible Consumers: The Role of Personal Values. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitta, L.; Probst, T.M.; Barbaranelli, C. Safety Culture, Moral Disengagement, and Accident Underreporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Hu, J.; Hong, Y.; Liao, H.; Liu, S. Do it well and do it right: The impact of service climate and ethical climate on business performance and the boundary conditions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzel, M.J.; Bearden, W.O. Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Lessig, V.P. Students and Housewives: Differences in Susceptibility to Reference Group Influence. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousineau, A.; Burnkrant, R.E. Informational and Normative Social Influence in Buyer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive Consumer Choice Processes. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; Montaña, J.; Sierra, V. Brand building by associating to public services: A reference group influence model. J. Brand Manag. 2006, 13, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Rao, A.R. The Influence of Familial and Peer-Based Reference Groups on Consumer Decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, X.; Lee, H. Social Reference Group Influence on Mobile Phone Purchasing Behaviour: A Cross-Nation Comparative Study. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2007, 5, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, A.M.; Salleh, S.M.; Halim, F. Linkages between Political Brand Image, Affective Commitment and Electors Loyalty: The Moderating Influence of Reference Group. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2016, 5, 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mcshane, B.B.; Berger, J. Visual Influence and Social Groups. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 854–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, A.A.; Panama, A.E.; Akemu, E. Green Awareness and Consumer Purchase Intention of Environmentally-Friendly Electrical Products in Anambra, Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2017, 8, 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerl, M.; Dorner, F.; Foscht, T.; Brandstätter, M. Attribution of symbolic brand meaning: The interplay of consumers, brands and reference groups. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yu, C. How Do Reference Groups Influence Self-Brand Connections among Chinese Consumers? J. Advert. 2012, 41, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigin, I.; Carrigan, M.; Mceachern, M.G. The conscious consumer: Taking a flexible approach to ethical behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 33, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, K.; Justin, W. Excluded and behaving unethically: Social exclusion, physiological responses, and unethical behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 547. [Google Scholar]

- Kavak, B.; Gürel, E.; Eryiğit, C.; Tektaş, Ö.Ö. Examining the Effects of Moral Development Level, Self-Concept, and Self-Monitoring on Consumers’ Ethical Attitudes. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.-C.; Lien, C.-H.; Cao, Y. Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on WeChat: Examining the influence of sense of belonging, need for self-enhancement, and consumer engagement on Chinese travellers’ eWOM. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 38, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, Z.; Mourali, M. Consumer Adoption of New Products: Independent Versus Interdependent Self-Perspectives. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooten, D.B.; Reed, A. Playing It Safe: Susceptibility to Normative Influence and Protective Self-Presentation. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Studies in the Principles of Judgments and Attitudes: II. Determination of Judgments by Group and by Ego Standards. J. Soc. Psychol. 1940, 12, 433–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, W.R.; Taylor, D.M.; Douglas, R.L. Normative Influence and Rational Conflict Decisions: Group Norms and Cost-Benefit Analyses for Intergroup Behavior. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2005, 8, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Vitell, S.J. The General Theory of Marketing Ethics: A Revision and Three Questions. J. Macromark. 2006, 26, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, L. The Two-Fold Influence of Sanctions on Moral Norms. In Psychological Perspectives on Ethical Behavior & Decision Making; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.L.P.; Sutarso, T. Falling or Not Falling into Temptation? Multiple Faces of Temptation, Monetary Intelligence, and Unethical Intentions Across Gender. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. The Role of Moral Judgments Within Expectancy-Value-Based Attitude-Behavior Models. Ethics Behav. 2002, 12, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Biderman, M.D. Studying Ethical Judgments and Behavioral Intentions Using Structural Equations: Evidence from the Multidimensional Ethics Scale. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Hao, Z.; Miao, Q. Personal Motives, Moral Disengagement, and Unethical Decisions by Entrepreneurs: Cognitive Mechanisms on the “Slippery Slope”. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, A.G.; Galletta, D.F.; Thong, J.Y.L. Software Piracy in the Workplace: A Model and Empirical Test. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, H.O.; Aksoy, E.; Itani, Y. The Muncy–Vitell Consumer Ethics Scale: A Modification and Application. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 62, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, R.Y.; Koh, S.; Paunonen, S.V. Supernumerary personality traits beyond the Big Five: Predicting materialism and unethical behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.N.K.; Jones, K. Ethical Awareness of Seller’s Behavior in Consumer-to-Consumer Electronic Commerce: Applying the Multidimensional Ethics Scale. J. Internet Commer. 2017, 16, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, T.T.; Chang, C.J. Ethical Decision Making in Software Piracy: Initial Development and Test of a Four-Component Model. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.; Dewe, P. An Investigation of the Components of Moral Intensity. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.R. Moral Emotions and Unethical Bargaining: The Differential Effects of Empathy and Perspective Taking in Deterring Deceitful Negotiation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Ahmad, N.Y. Using Empathy to Improve Intergroup Attitudes and Relations. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2010, 3, 141–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rafee, S.; Cronan, T.P. Digital Piracy: Factors that Influence Attitude Toward Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 63, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, V.; Hughes, N.; Palmer, E.J. Moral disengagement, the dark triad, and unethical consumer attitudes. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claybourn, M. Relationships Between Moral Disengagement, Work Characteristics and Workplace Harassment. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.; Detert, J.R.; Trevino, L.K.; Baker, V.L.; Mayer, D.M. Why Employees Do Bad Things: Moral Disengagement And Unethical Organizational Behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 3, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Dennis, C. Unethical consumers. Qual. Mark. Res. 2006, 9, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Ajzen, I. Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. J. Res. Personal. 1991, 25, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, L. Trait anger and cyberbullying among young adults: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and moral identity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, K.E.; Smeesters, D.; Mandel, N. Still Preoccupied with 1995: The Need to Belong and Preference for Nostalgic Products. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. Moral Disengagement in Processes of Organizational Corruption. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, A.; Morales, J.F.; Hart, S.; Vázquez, A.; Jr, S.W. Rejected and excluded forevermore, but even more devoted: Irrevocable ostracism intensifies loyalty to the group among identity-fused persons. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1574–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, M.; Lord, R.G.; Petersen, L.; Weigelt, O. Examining the moral grey zone: The role of moral disengagement, authenticity, and situational strength in predicting unethical managerial behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusche, A.; Böckler, A.; Kanske, P.; Trautwein, F.M.; Singer, T. Decoding the Charitable Brain: Empathy, Perspective Taking, and Attention Shifts Differentially Predict Altruistic Giving. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 4719–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, A. Moral cognition and moral action: A theoretical perspective. Dev. Rev. 1983, 3, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A. The self-importance moral identity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.J.; Winterich, K.P. Can Brands Move In from the Outside? How Moral Identity Enhances Out-Group Brand Attitudes. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2013, 77, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Bean, D.S.; Olsen, J.A. Moral Identity and Adolescent Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors: Interactions with Moral Disengagement and Self-regulation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Americus Reed, I.I.; Thau, S.; Dan, F. A grotesque and dark beauty: How moral identity and mechanisms of moral disengagement influence cognitive and emotional reactions to war. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguezrad, C.J.; Hidalgo, E.R. Spirituality, consumer ethics, and sustainability: The mediating role of moral identity. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 35, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Linda Klebe, T.O.; Sweitzer, V.L. Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J.; King, R.A.; Howie, K.; Toti, J.F.; Albert, L.; Hidalgo, E.R.; Yacout, O. Spirituality, Moral Identity, and Consumer Ethics: A Multi-cultural Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobwitz, S.; Egan, V. The dark triad and normal personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L.; Lutterman, K.G. The Traditional Socially Responsible Personality. Public Opin. Q. 1968, 32, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Jeong-Yeon, L.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review of the Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Performance and Satisfaction in an Industrial Sales Force: An Examination of Their Antecedents and Simultaneity. J. Mark. 1980, 44, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Toothaker, L.E. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1994, 45, 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Dong, W.; Jie, W.; Liang, D.; Yin, X. Confucian Ideal Personality and Chinese Business Negotiation Styles: An Indigenous Perspective. Group Decis. Negot. 2014, 24, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rosen, S. Confucian philosophy and contemporary Chinese societal attitudes toward people with disabilities and inclusive education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2018, 50, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Mean | SD | GR | GV | EM | AM | MD | MI | UBI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR | 4.074 | 1.810 | 0.876 | (0.939) | ||||||

| GV | 4.410 | 1.688 | 0.817 | 0.070 | (0.827) | |||||

| EM | 3.404 | 1.705 | 0.828 | 0.585 ** | −0.103 | (0.883) | ||||

| AM | 5.383 | 1.566 | 0.837 | −0.330 ** | 0.434 ** | −0.391 ** | (0.891) | |||

| MD | 2.968 | 1.743 | 0.826 | 0.589 ** | −0.184 * | 0.772 ** | −0.580 ** | (0.916) | ||

| MI | 5.745 | 1.377 | 0.889 | 0.207 ** | 0.231 ** | 0.032 | 0.164 * | 0.018 | (0.931) | |

| UBI | 3.622 | 2.092 | 0.971 | 0.440 ** | −0.235 ** | 0.476 ** | −0.375 ** | 0.614 ** | 0.071 | (0.969) |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | Δχ2 | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-factor model | 3856.732 | 560 | 6.887 | 556.287 *** | 0.181 | 0.391 | 0.353 | 0.395 |

| Two-factor model | 3300.445 | 559 | 5.904 | 276.558 *** | 0.166 | 0.494 | 0.461 | 0.497 |

| Three-factor model | 3023.887 | 557 | 5.429 | 790.758 *** | 0.157 | 0.545 | 0.514 | 0.548 |

| Four-factor model | 2233.129 | 554 | 4.031 | 474.482 *** | 0.130 | 0.690 | 0.667 | 0.692 |

| Five-factor model | 1758.647 | 550 | 3.198 | 330.778 *** | 0.111 | 0.777 | 0.759 | 0.779 |

| Six-factor model | 1427.869 | 545 | 2.620 | 416.474 *** | 0.095 | 0.837 | 0.822 | 0.838 |

| Seven-factor model | 1011.395 | 539 | 1.876 | 0.071 | 0.912 | 0.902 | 0.913 | |

| Structural model | 700.143 | 357 | 1.961 | 0.073 | 0.921 | 0.910 | 0.922 |

| Paths | Coefficient Beta | F Value | R2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group recognition→Unethical behavioural intention | 0.405 | 10.313 | 0.265 | <0.001 |

| Group veto→Unethical behavioural intention | −0.258 | 5.825 | 0.169 | <0.001 |

| Egoism motivation→Unethical behavioural intention | 0.349 | 8.062 | 0.219 | <0.001 |

| Altruistic motivation→Unethical behavioural intention | −0.354 | 8.535 | 0.229 | <0.001 |

| Paths | Indirect Effect | Standard Error | 95% Bootstrapped Confidence Interval | Direct Effect | Standard Error | 95% Bootstrapped Confidence Interval | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR—MD—UBI | 0.271 *** | 0.054 | [0.176; 0.391] | 0.138 | 0.073 | [−0.006; 0.282] | Full |

| GV—MD—UBI | −0.123 ** | 0.046 | [−0.218; −0.040] | −0.132 | 0.062 | [−0.254; −0.011] | Partial |

| AM—MD—UBI | 0.382 *** | 0.065 | [0.257; 0.511] | −0.029 | 0.082 | [−0.190; 0.133] | Full |

| EM—MD—UBI | −0.307 *** | 0.058 | [−0.441; −0.209] | −0.041 | 0.074 | [−0.187; 0.105] | Full |

| Variables | Moral Disengagement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Controlled variable | |||||||

| Sex | −0.262 *** | −0.225 ** | −0.123 * | −0.217 * | −0.130 ** | −0.208 ** | −0.134 ** |

| Gender | −0.101 | −0.010 | −0.082 | −0.007 | −0.085 | −0.014 | −0.115 |

| Marriage | −0.014 | −0.019 | −0.033 | −0.027 | −0.020 | −0.015 | −0.018 |

| Education | 0.139 | 0.063 | 0.090 | 0.062 | 0.093 * | 0.047 | 0.095 * |

| Income | 0.147 | 0.094 | 0.112 | 0.095 | 0.110 | 0.117 | 0.117 * |

| Independent variables | |||||||

| GR | 0.563 *** | 0.574 *** | 0.545 *** | ||||

| GV | −0.258 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.218 *** | ||||

| EM | 0.517 *** | 0.509 *** | 0.476 | ||||

| AM | −0.410 *** | −0.425 *** | −0.424 | ||||

| Moderator | |||||||

| MI | −0.053 | 0.071 | −0.091 | 0.053 | |||

| Interaction terms | |||||||

| GR*MI | 0.061 | ||||||

| GV*MI | −0.151 * | ||||||

| EM*MI | 0.052 | ||||||

| AM*MI | −0.142 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.139 | 0.491 | 0.671 | 0.493 | 0.675 | 0.508 | 0.693 |

| ΔR2 | 0.139 | 0.352 *** | 0.532 *** | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.018 ** |

| Moderator | GV—UBI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Level of Moral Identity | −0.004 [−0.266, 0.140] | −0.074 [−0.477, 0.254] | −0.001 [−0.073, 0.045] | −0.075 [−0.517, 0.220] |

| High Level of Moral Identity | −0.219 *** [−0.479, −0.040] | −0.125 * [−0.250, −0.010] | −0.107 *** [−0.272, −0.015] | −0.232 [−0.478, −0.046] |

| Differences | −0.215 *** [−0.358, −0.001] | −0.051 [−0.24,0.251] | −0.106 ** [−0.182, −0.020] | −0.157 [−0.353, 0.174] |

| Moderator | AM—UBI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Level of Moral Identity | −0.374 *** [−0.658, −0.190] | 0.017 [−0.505, 0.283] | −0.096 [−0.307, 0.168] | −0.079 [−0.438, 0.252] |

| High Level of Moral Identity | −0.578 *** [−0.760, −0.348] | −0.049 [−0.280, 0.130] | −0.277 *** [−0.414, −0.136] | −0.326 *** [−0.517, −0.101] |

| Differences | −0.204 [−0.330, 0.140] | −0.066 [−0.242, 0.227] | −0.181 *** [−0.294, −0.038] | −0.247 ** [−0.395, −0.023] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Zhang, J. Acquiescence or Resistance: Group Norms and Self-Interest Motivation in Unethical Consumer Behaviour. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082190

Sun Y, Zhang J. Acquiescence or Resistance: Group Norms and Self-Interest Motivation in Unethical Consumer Behaviour. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082190

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yongbo, and Jiajia Zhang. 2019. "Acquiescence or Resistance: Group Norms and Self-Interest Motivation in Unethical Consumer Behaviour" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082190

APA StyleSun, Y., & Zhang, J. (2019). Acquiescence or Resistance: Group Norms and Self-Interest Motivation in Unethical Consumer Behaviour. Sustainability, 11(8), 2190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082190