Event and Sustainable Culture-Led Regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Culture and Sustainability

2.2. Culture-Led Regeneration

2.3. Dilemmas of Culture-Led Regeneration

3. Research Methods

4. Research Findings

4.1. The Issue of Cultural Funding Dilemma

4.2. The Issue of Economic Dilemma

4.3. The Issue of Spatial Dilemma

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duxbury, N.; Cullen, C.; Pascual, J. Cities, culture and sustainable development. In Cultures and Globalization: Cities, Cultural Policy and Governance; Anheier, H.K., Isar, Y.R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012; pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Palmer, R. Eventful Cities: Cultural Management and Urban Revitalization; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yudice, G. The Expediency of Culture: Uses of Culture in the Global Era; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Cultures of Cities; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. Measure for measure: Evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M. ‘Urban Regeneration’ to ‘Social Regeneration’: Culture and Social Regeneration through the Culture City of East Asia Event Initiative in Cheongju South Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, F.; Parkinson, M. Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Deffner, A.M.; Labrianidis, L. Planning culture and time in a mega-event: Thessaloniki as the European City of Culture in 1997. Int. Plan. Stud. 2005, 10, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dova, E. Organizing Public Space as a Framework for Re-Thinking the City: Pafos’s Bid for the 2017 European Capital of Culture. 2013. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11728/8988 (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- García, B. Cultural policy and urban regeneration in Western European Cities. Local Econ. 2004, 19, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, O.; Džupka, P. Culture-led regeneration through the young generation: Košice as the European Capital of Culture. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechita, F. Bidding for the European Capital of Culture: Common Strengths and Weaknesses at the Pre-Selection Stage; Series VII: Social Sciences, Law, 8; Bulletin of the Transilvania University: Brasov, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolaou, P. The European Capital of Culture: The challenge for urban regeneration and its impact on the cities. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, M.; McGillivray, D.; McPherson, G. Event Policy: From Theory to Strategy; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi-Vallbona, M.; Richards, G. The meaning of cultural festivals: Stakeholder perspectives in Catalunya. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer/Rae. European Cities and Capitals of Culture: Study Prepared for the European Commission; Part 1; Palmer/Rae Associates: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- García, B. Deconstructing the city of culture: The long-term cultural legacies of Glasgow 1990. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impacts 08. Creating an Impact: Liverpool’s Experience as European Capital of Culture; Impacts 08: Liverpool, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nobili, V. The role of European Capital of Culture events within Genoa’s and Liverpool’s branding and positioning efforts. Place Brand. 2005, 1, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.L. Cities of Culture and the regeneration game. Lond. J. Tour. Sport Creat. Ind. 2011, 5, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T.; O’Brien, D. The “scouse wedding” and other myths: Reflections on the evolution of a “Liverpool model” for culture-led urban regeneration. Cult. Trends 2012, 21, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D. Who is in charge? Liverpool, European Capital of Culture 2008 and the governance of cultural planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2011, 82, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, W.; Henry, I.; Jackson, G.; Goytia Prat, A.; Richards, G.; van der Straaten, J. Sustainable Tourism Management: Principles and Practice; Tilburg University Press: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Burksiene, V.; Dvorak, J.; Burbulyte-Tsiskarishvili, G. Sustainability and sustainability marketing in competing for the title of European Capital of Culture. Organizacija 2018, 51, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground Publishing: Altona, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cubeles, X.; Baro, F. Culture and Sustainability; Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DCMS. Sustainable Development Strategy: Arts. Available online: www.culture.gov.uk/images/publications/SDSARTS.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Council of Europe. In from the Margins: A Contribution to the Debate on Culture and Development in Europe; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development. Small States Econ. Rev. Basic Stat. 2006, 1, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fithian, C.; Powell, A. Cultural Aspects of Sustainable Development. Available online: http://webmail.seedengr.com/Cultural%20Aspects%20of%20Sustainable%20Development.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Sazonova, L. Cultural Aspects of Sustainable Development: Glimpses of the Ladies’ Market; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dessein, J.; Soini, K.; Fairclough, G.; Horlings, L. (Eds.) Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development; Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, C.D. On the Sustainability of Cultural Capital; Department of Economics, Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia, 2005; Volume 510. [Google Scholar]

- UCLG. Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable; UCLG Policy Statement, UCLG Committee on Culture and World Secretariat Policy Statement for Mexico City, United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG): Barcelona, Spain, 2010.

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.J.; Clark, T.N. Cultural policies in European cities. Eur. Soc. 2012, 14, 636–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, A. Urban Regeneration in the UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, P.C.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Cultural urban regeneration practice and policy in the UK and Singapore. Asia Pac. J. Arts Cult. Manag. 2010, 7, 512–527. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, C. Culture in the city, culture for the city? The political construction of the trickle-down in cultural regeneration strategies in Roubaix, France. Town Plan. Rev. 2011, 82, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.L.; Shaw, P. A Review of Evidence on the Role of Culture in Regeneration; Department for Culture Media and Sport: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dinardi, C. Unsettling the role of culture as panacea: The politics of culture-led urban regeneration in Buenos Aires. City Cult. Soc. 2015, 6, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. From cultural quarters to creative clusters: Creative spaces in the New City economy. In The Sustainability and Development of Cultural Quarters: International Perspectives; Legner, M., Ed.; Institute of Urban History: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; pp. 32–59. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Cultural quarters as mechanisms for urban regeneration. Part 1: Conceptualising cultural quarters. Plan. Pract. Res. 2003, 18, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. Cultural quarters as mechanisms for urban regeneration. Part 2: A review of four cultural quarters in the UK, Ireland and Australia. Plan. Pract. Res. 2004, 19, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunay, Z.; Dokmeci, V. Culture-led regeneration of Istanbul waterfront: Golden horn cultural valley project. Cities 2012, 29, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickery, J. The Emergence of Culture-Led Regeneration: A Policy Concept and Its Discontents; Centre for Cultural Policy Studies, University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, K.; Smith, I.; Banks, M.; O’Connor, J. Urban dilemmas of competition and cohesion in cultural policy. In Changing Cities: Rethinking Urban Competitiveness, Cohesion and Governance; Buck, N., Gordon, I., Harding, A., Turok, I., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2005; pp. 132–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Forbici, S. Power to the people: When culture works as a social catalyst in urban regeneration processes (and when it does not). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Hard-branding the cultural city: From Prado to Prada. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F. Remaking European cities: The role of cultural policies. In Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience; Bianchini, F., Parkinson, M., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1993; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, L. Capitalising on Culture: An Evaluation of Culture-Led Urban Regeneration Policy; Dublin Institute of Technology: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class; Basic Books/Perseus: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Della Lucia, M.; Trunfio, M. The role of the private actor in cultural regeneration: Hybridizing cultural heritage with creativity in the city. Cities 2018, 82, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M.; Di Trapani, G. Cultural tourism and creative regeneration: Two case studies. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 4, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Wilson, J. Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.A. Rotterdam: Redesigning the public domain. In Cultural Policy and Regeneration: The West European Experience; Bianchini, F., Parkinson, M., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1993; pp. 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, K.; Hughes, M.; Mair, J.; Carlsen, J. Events and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C.; Greene, L.; Matarasso, F.; Bianchini, F. The Art of Regeneration: Urban Renewal through Cultural Activity; Comedia: Stoud, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- DCMS. Culture at the Heart of Regeneration; Department of Culture, Media & Sports (DCMS): London, UK, 2003.

- Arts Council England. Arts and Regeneration: Creating Vibrant Communities; Arts Council England (ACE): London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ecorys. Ex-Post Evaluation of 2007 & 2008 European Capitals of Culture: Final Report; Ecorys: Birmingham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, C. Urban regeneration in Liverpool. In Urban Regeneration in Europe; Couch, C., Fraser, C., Percy, S., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- García, B.; Cox, T. European Capitals of Culture: Success Strategies and Long-Term Effects; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, P. Creative industries in a European Capital of Culture. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2011, 17, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.; Cox, T.; O’Brien, D. The social life of measurement: How methods have shaped the idea of culture in urban regeneration. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.G. The ‘Liverpool model(s)’: Cultural planning, Liverpool and Capital of Culture 2008. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2013, 19, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D. ‘No cultural policy to speak of’–Liverpool 2008. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2010, 2, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.; Miles, S. Cultural policy as rhetoric and reality: a comparative analysis of policy making in the peripheral north of England. Cult. Trends 2010, 19, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, P. ‘Capital of Culture- you must be having a laugh!’ Challenging the official rhetoric of Liverpool as the 2008 European cultural capital. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2010, 11, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impacts 08. Media Impact Assessment (Part II): Evolving Press and Broadcast Narratives on Liverpool from 1996 to 2009; Impacts 08: Liverpool, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

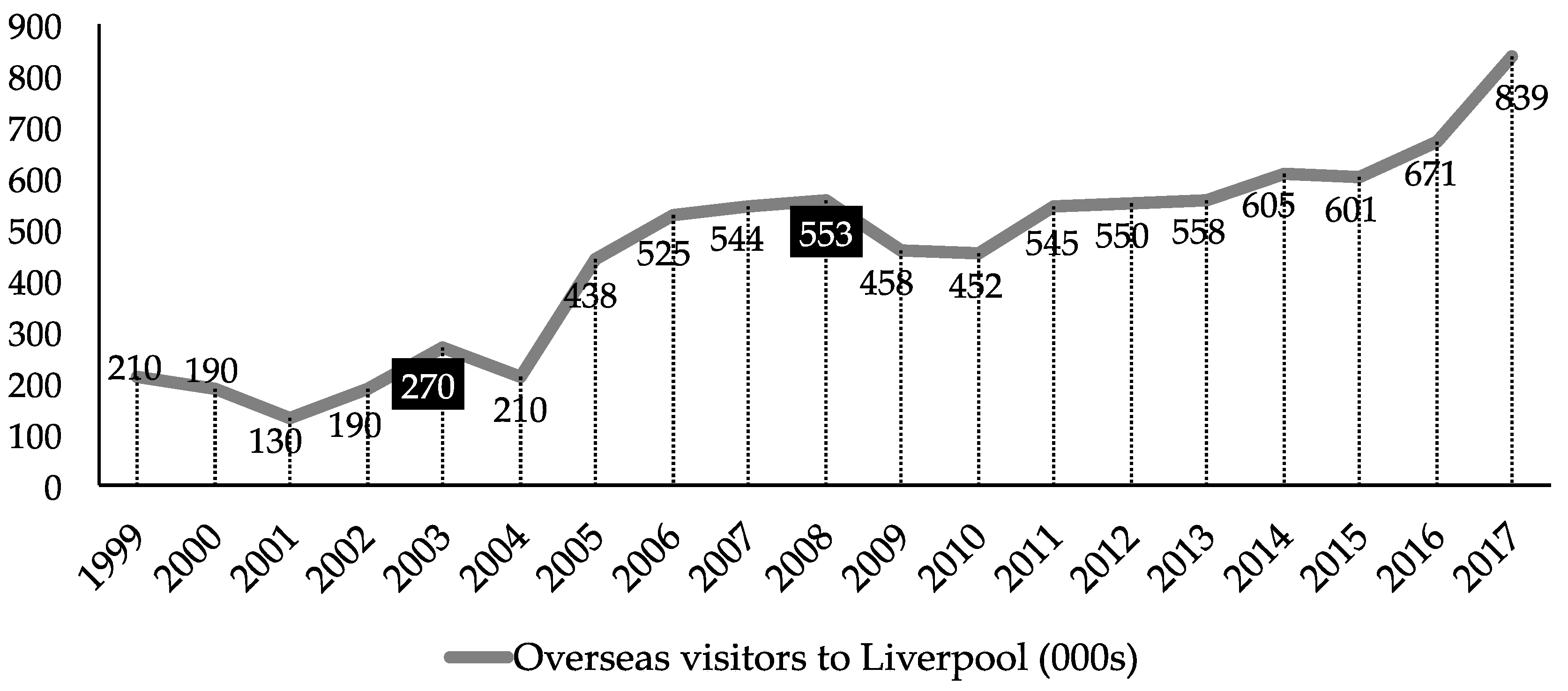

- Visit Britain. Top Town for Staying Visits by Inbound Visitors. Available online: https://www. visitbritain.org/town-data. (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Oerters, K.; Mittag, J. European Capitals of Culture as incentives for local transformation and creative economies. In Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference of the University Network of ECoC, Liverpool, UK, 16–17 October 2008; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Impacts 08. Liverpool’s Creative Industries: Understanding the Impact of Liverpool European Capital of Culture 2008 on the City Region’s Creative Industries; Impacts 08: Liverpool, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, C. European Capitals of Culture and Everyday Cultural Diversity: A Comparison of Liverpool (UK) and Marseilles (France); European Cultural Foundation: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Impacts 08. Neighbourhood Impacts: A Longitudinal Research Study into the Impact of the Liverpool European Capital of Culture on Local Residents; Impacts 08: Liverpool, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Communities. European Capitals of Culture: The Road to Success from 1985 to 2010; Publications Office of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Impacts 18. Legacies of Liverpool as European Capital of Culture, 10 Years on. Available online: http://iccliverpool.ac.uk/impacts18 (accessed on 1 July 2018).

- Landry, C.; Bianchini, F. The Creative City; Demos: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| Types | Key Elements |

|---|---|

| Agencies | Liverpool Culture Company → Culture Liverpool |

| Networks | Liverpool Arts Regeneration Consortium (LARC), Mersey Partnership |

| Events | Eight themed years: Year of Learning (2003), Year of Faith (2004), Year of Sea (2005), Year of Performance (2006), Year of Heritage (2007), ECOC Year (2008), Year of Environment (2009), and Year of Health, Well-Being & Innovation (2010) |

| Initiatives | Creative Community, Four Corners, 08 Welcome, 08 Volunteer |

| Parallel regeneration | Arena and Convention Centre Liverpool (ACCL), Liverpool ONE, Museum of Liverpool, Bluecoat Art Centre |

| Survey Items | Survey Result * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2009 | 2018 | |

| Participation in the Liverpool 08 event programmes | n.a. | 66% | n.a. |

| More interested in cultural activities because of the ECOC | n.a. | 37% | 44% |

| Attending galleries | 60% | 69% | n.a. |

| Attending museums | 42% | 52% | n.a. |

| Attending live events | 35% | 53% | n.a. |

| Everyone in Liverpool will gain from the ECOC | 42% | 46% | 63% |

| Only the city centre will benefit from the ECOC | 66% | 56% | n.a. |

| The ECOC won’t make any difference to the neighbourhood | 63% | 57% | n.a. |

| The city is a much better place after the ECOC | 56% | 57% | 81% |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.-D. Event and Sustainable Culture-Led Regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071869

Liu Y-D. Event and Sustainable Culture-Led Regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071869

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yi-De. 2019. "Event and Sustainable Culture-Led Regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071869

APA StyleLiu, Y.-D. (2019). Event and Sustainable Culture-Led Regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool. Sustainability, 11(7), 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071869