Company’s Sustainability and Accounting Conservatism: Firms Delisting from KOSDAQ

Abstract

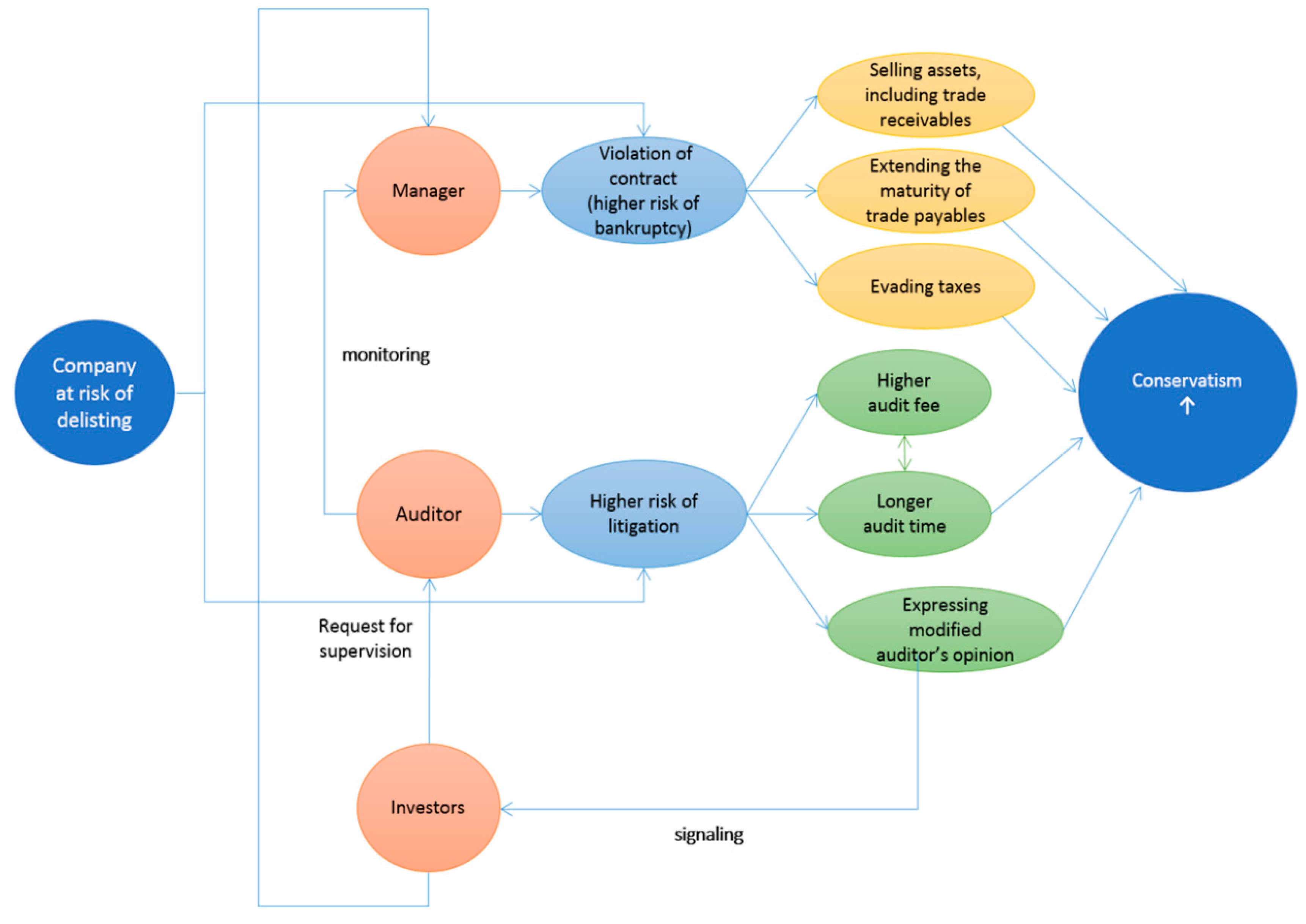

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Prior Studies

3. Development of Hypotheses

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Study Design

- TACC: total accruals (total accruals are the change in non-cash current assets, less the change in current liabilities (exclusive of short-term debt and taxes payable), less depreciation, and amortization expense.) divided by total asset at the beginning of the fiscal year

- CFO: operating cash flow divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- DCFO: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if CFO is negative or 0 otherwise

- DELIST: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm is about to be delisted or 0 otherwise

- BIG4: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s auditor is a Big4 or 0 otherwise

- ΔREV: change of sales divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- PPE: property, plant, and equipment, divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- TACC: total accruals divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- CFO: operating cash flow divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- DCFO: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if CFO is negative or 0 otherwise

- SUBST: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm is about to be delisted by substantial investigation or 0 otherwise

- ΔREV: change of sales divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- PPE: property, plant, and equipment, divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

4.2. Selection of Samples

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

5.2. Difference Analysis

5.3. Companies Ahead of Delisting and Conservatism

5.4. Additional Analysis

- X: annual earnings per share for firm i in year t

- P: price per share for firm i in year t − 1

- RET: annual stock returns cumulated over 12 months from April in year t to March in year t + 1

- DRET: 1 if RET < 0 and 0 otherwise

- DELIST: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm is about to be delisted or 0 otherwise

- BIG4: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s auditor is a Big4 or 0 otherwise.

- SUBST: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm is about to be delisted by substantial investigation or 0 otherwise

- GHCON: Givoly and Hayn (2000) conservatism (GHCONit = (−1) × (TAit − OAit)/ASSETi,t−1)

- DELIST: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm is about to be delisted or 0 otherwise

- SIZE: natural log of total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- LEV: total debt divided by total equity at the beginning of the fiscal year

- ∆REW: growth rate of sales

- OCF: operating cash flow divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year

- RLS: the ratio of the largest shareholder and related party ownership at the beginning of the fiscal year

- ALTMAN: Altman (1968) Z score

- BIG4: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s auditor is a Big4 or 0 otherwise

- LOSS: dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s net income is negative or 0 otherwise

- IN: Industry dummy variable

- YR: Year dummy variable.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sohn, S.K.; Yum, J.I. Delisting Risk in the KOSDAQ Market and Earnings Management. Korean Account. Rev. 2013, 38, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Ji, H.M. The Effect of Substantial Investigation System of Delisting on Reliability of Accounting Information. J. Tax. Account. 2010, 11, 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.W.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, Y.G. An Empirical Study on Characteristics of Delisted Companies. Korean Account. J. 2011, 20, 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, S.P.; Leone, A.J.; Wasley, C.E. Performance Matched Discretionary Accrual Measures. J. Account. Econ. 2005, 39, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.T.; Lee, J.H. A Study on the Substantial Delisting and the Patterns of Earnings Management: A Case in the KOSDAQ Firms. Account. Inf. Rev. 2012, 30, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, M.; Leone, A.J.; Willenborg, M. An Empirical Analysis of Auditor Reporting and its Association with Abnormal Accruals. J. Account. Econ. 2004, 37, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S. Systematic Measurement Error in the Estimation of Discretionary Accruals: An Evaluation of Alternative Modelling Procedures. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 1999, 26, 833–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.I.; Jung, Y.J.; Kim, H.S.; Moon, S.H. Differences in Conservatism between Big5 and Non-Big5 Auditors. Study Account. Tax. Audit. 2002, 38, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, X. The Effect of Contracting, Litigation, Regulation, and Tax Costs on Conditional Unconditional Conservatism: Cross-Sectional Evidence at the Firm Level. Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 759–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Shawn, H.; Lee, H.I. Unqualified Opinion with Going Concern Explanatory Paragraph and Conservatism. Korean Account. J. 2013, 22, 77–105. [Google Scholar]

- Holthausen, R.W.; Watts, R.L. The Relevance of the Value-Relevance Literature for Financial Accounting Standard Setting. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 3–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero., J.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B. Effect of Financial Reporting Quality on Sustainability Information Disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. 2015, 22, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavana., G.; Gottardo, P.; Moisello, A. Earnings Management and CSR Disclosure. Family vs. Non-Family Firms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Shivakumar, L. Earnings quality in UK Private Firms: Comparative Loss Recognition Timeliness. J. Account. Econ. 2005, 39, 83–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Shivakumar, L. Earnings Quality at Initial Public Offerings. J. Account. Econ. 2008, 45, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S. The Conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. J. Account. Econ. 1997, 24, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givoly, D.; Hayn, C. The Changing Time-Series Properties of earnings, Cash Flows and Accruals: Has Financial Reporting Become More Conservative? J. Account. Econ. 2000, 29, 287–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.S. A Comparison of Earnings Management between KSE Firms and KOSDAQ Firms. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2005, 32, 1347–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J. The Effect of Substantial Investigation System of Delisting on Auditor Switching. Korea J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 24, 3351–3368. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, R.L. Conservatism in Accounting Part II: Evidence and Research Opportunities. Account. Horiz. 2003, 17, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.; Zimmerman, J. Positive Accounting Theory: A Ten Year Perspective. Account. Rev. 1990, 65, 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S.; Hwang, L.; Jan, C. Differences in Conservatism between Big Eight and Non-Big Eight Auditors; Working Paper; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R.; Shivakumar, L. The Role of Accruals in Asymmetrically Timely Gain and Loss Recognition. J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, L.E. Auditor Size and Audit Quality. J. Account. Econ. 1981, 3, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.L.; DeFond, M.L.; Jiambalvo, J.; Subramanyam, K.R. The Effect of Audit Quality on Earnings Management. Contemp. Account. Res. 1998, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, C.K. Informativeness of Discretionary Accruals Depending on Accruals Quality and Auditor Types. Korean Account. Rev. 2004, 29, 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Paek, W.S.; Lee, S.R. Conservatism, Earnings Persistence and Equity Valuation. Korean Account. Rev. 2004, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dechow, P.M.; Kothari, S.P.; Watts, R. The Relation between Earnings and Cash Flows. J. Account. Econ. 1998, 25, 133–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. Financial Ratios, Discriminate Analysis and the Prediction of Corporate Bankruptcy. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizińska, J.; Czapiewski, L. Towards economic corporate sustainability in reporting: What does earnings management around equity offerings mean for long-term performance? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4349. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.O.; Bae, G.S. The Relationship between Conservatism and Accruals. Korean Account. J. 2009, 18, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

| Panel A: Sample Selection | ||||||||||

| Sample Characteristics | Number of Firm-Year Observations | |||||||||

| Number of firm-year observations | 10,864 | |||||||||

| Other year-end | (1023) | |||||||||

| Unavailable data | (3493) | |||||||||

| Total | 6348 | |||||||||

| Panel B: Yearly Delisting Samples | ||||||||||

| Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |

| Substantial investigation | 16 | 28 | 15 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 99 | |

| Formal delisting criteria | 49 | 47 | 43 | 14 | 27 | 12 | 20 | 19 | 231 | |

| Total | 65 | 75 | 58 | 28 | 33 | 15 | 32 | 24 | 330 | |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | 1st Quartile | Median | 3rd Quartile | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DELIST | 0.076 | 0.266 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| BIG4 | 0.428 | 0.495 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| SUBST | 0.019 | 0.137 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| TACC | −0.046 | 0.145 | −1.116 | −0.097 | −0.030 | 0.030 | 0.396 |

| CFO | 0.044 | 0.107 | −0.551 | −0.014 | 0.045 | 0.105 | 0.384 |

| DCFO | 0.300 | 0.458 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| ∆REV | −0.055 | 0.263 | −1.271 | −0.159 | −0.034 | 0.067 | 0.897 |

| PPE | 0.157 | 0.129 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.127 | 0.225 | 0.677 |

| DELIST | BIG4 | SUBST | TACC | CFO | DCFO | △REV | PPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DELIST | −0.092 *** | 0.485 *** | −0.240 *** | −0.225 *** | 0.196 *** | 0.017 | −0.068 *** | |

| BIG4 | −0.081 *** | 0.040 *** | 0.118 *** | −0.088 *** | −0.012 | 0.031 ** | ||

| SUBST | −0.167 *** | −0.167 *** | 0.130 *** | −0.009 | −0.058 *** | |||

| TACC | −0.240 *** | 0.156 *** | −0.062 *** | 0.017 | ||||

| CFO | −0.725 *** | −0.088 *** | 0.129 *** | |||||

| DCFO | 0.041 *** | −0.118 *** | ||||||

| △REV | −0.067 *** | |||||||

| PPE |

| Variables | Group | Mean | Std. | t-Value | z-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIG4 | DELIST = 1 | 0.270 | 0.444 | −0.041 *** | 3.608 *** |

| DELIST = 0 | 0.441 | 0.496 | |||

| SUBST | DELIST = 1 | 0.249 | 0.433 | 12.684 *** | 5.280 *** |

| DELIST = 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| TACC | DELIST = 1 | −0.167 | 0.242 | −11.794 *** | 6.655 *** |

| DELIST = 0 | −0.036 | 0.129 | |||

| CFO | DELIST = 1 | −0.040 | 0.134 | −14.509 *** | 7.237 *** |

| DELIST = 0 | 0.051 | 0.102 | |||

| DCFO | DELIST = 1 | 0.612 | 0.488 | 14.772 *** | 7.160 *** |

| DELIST = 0 | 0.274 | 0.446 | |||

| ∆REV | DELIST = 1 | −0.039 | 0.290 | 1.262 | 1.612 ** |

| DELIST = 0 | −0.056 | 0.261 | |||

| PPE | DELIST = 1 | 0.127 | 0.126 | −5.541 *** | 3.336 *** |

| DELIST = 0 | 0.160 | 0.129 |

| Variable | Ball and Shivakumar (2005) | Ball and Shivakumar (2008) |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate (t-Stat) | Parameter Estimate (t-Stat) | |

| Intercept | −0.014 * (−1.956) | −0.032 *** (−4.792) |

| CFO | −0.492 *** (−17.185) | −0.525 *** (−18.187) |

| ∆REV | −0.051 *** (−7.880) | |

| PPE | −0.002 (−0.143) | |

| DCFO | −0.001 (−0.140) | −0.001 (−0.150) |

| DCFO × CFO | −0.016 (−0.288) | 0.035 (0.622) |

| DLEIST | −0.138 *** (−9.009) | −0.140 *** (9.197) |

| DELIST × CFO | 0.340 ** (2.156) | 0.414 *** (2.628) |

| DELIST × DCFO | −0.053 *** (−2.608) | −0.053 ** (2.593) |

| DELIST × CFO × DCFO | 0.008 ** (0.041) | −0.082 (−0.449) |

| BIG4 | 0.011 *** (3.209) | 0.011 *** (3.170) |

| DELIST × BIG4 × CFO | 0.342 * (1.849) | 0.359 * (1.951) |

| DELIST × BIG4 × DCFO | 0.006 (0.195) | 0.009 (0.320) |

| DELIST × BIG4 × CFO × DCFO | −0.816 *** (−2.780) | −0.780 *** (−2.669) |

| ∑IND | included | |

| ∑YEAR | included | |

| F-stat. (Adjusted R-Square) | 35.191 (18.09%) | 35.320 (18.86%) |

| Variable | Ball and Shivakumar (2005) | Ball and Shivakumar (2008) |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate (t-Stat) | Parameter Estimate (t-Stat) | |

| Intercept | −0.013 * (−1.784) | −0.034 (−5.022) |

| CFO | −0.457 *** (−15.699) | −0.489 (−16.687) |

| ∆REV | −0.052 (−7.802) | |

| PPE | 0.005 (0.327) | |

| DCFO | −0.004 (−0.674) | −0.004 (−0.704) |

| DCFO × CFO | 0.123 ** (2.362) | 0.172 (3.299) |

| SUBST | −0.098 *** (−3.018) | −0.102 (−3.157) |

| SUBST × CFO | −0.372 (−1.048) | −0.345 (−0.978) |

| SUBST × DCFO | −0.111 *** (−2.763) | −0.108 (−2.705) |

| SUBST × CFO × DCFO | 0.662 * (1.735) | 0.618 (1.627) |

| ∑IND | included | |

| ∑YEAR | included | |

| F-stat. (Adjusted R-Square) | 24.685 *** (12.13%) | 25.214 *** (12.95%) |

| Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | t Value | Coefficient | t Value |

| Intercept | 0.041 | 3.154 *** | 0.040 | 3.103 *** |

| RET | −0.025 | −4.238 *** | −0.025 | −4.237 *** |

| DRET | −0.030 | −3.450 *** | −0.030 | −3.463 *** |

| RET × DRET | 0.175 | 9.091 *** | 0.175 | 9.084 *** |

| DELIST | −0.271 | −11.385 *** | −0.258 | −10.429 *** |

| DELIST × RET | −0.022 | −1.246 | −0.019 | −1.068 |

| DELIST × DRET | 0.192 | 4.898 *** | 0.190 | 4.838 *** |

| DELIST × DRET × RET | 0.504 | 8.560 *** | 0.495 | 8.384 *** |

| BIG4 | 0.019 | 3.130 *** | 0.019 | 3.100 *** |

| DELIST × BIG4 × RET | 0.056 | 2.144 ** | 0.054 | 2.042 ** |

| DELIST × BIG4 × DRET | −0.066 | −1.252 | −0.052 | −0.965 |

| DELIST × BIG4 × DRET × RET | −0.279 | −2.707 *** | −0.241 | −2.243 ** |

| SUBST | −0.054 | −2.047 ** | ||

| DELIST × BIG4 × SUBST × RET | −0.038 | −0.618 | ||

| DELIST × BIG4 × SUBST × DRET | −0.248 | −1.569 | ||

| DELIST × BIG4 × SUBST × RET × DRET | −0.431 | −1.424 | ||

| ∑IND | included | |||

| ∑YEAR | included | |||

| F-Value | 37.325 *** | 34.233 *** | ||

| Adj. R-Square | 19.53% | 19.07% | ||

| Variable | Coefficient | t Value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.355 | 8.113 *** |

| DELIST | 0.090 | 15.715 *** |

| SIZE | −0.036 | −8.799 *** |

| LEV | 0.079 | 11.020 *** |

| ∆REV | −0.028 | −5.879 *** |

| CFO | 0.266 | 20.668 *** |

| RLS | 0.000 | 2.285 ** |

| ALTMAN | 0.000 | −2.148 ** |

| BIG4 | 0.000 | −0.024 |

| LOSS | 0.086 | 27.762 *** |

| DELIST × BIG4 | −0.077 | −7.539 *** |

| ∑IND | included | |

| ∑YEAR | included | |

| F-Value | 58.318 *** | |

| Adj. R-Square | 26.54% | |

| Variable | H1 | H2 |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate (t-Stat.) | Parameter Estimate (t-Stat.) | |

| Intercept | 0.008 (0.921) | −0.001 (−0.070) |

| CFO | −0.592 *** (−20.564) | −0.572 *** (−19.654) |

| ∆REV | −0.056 *** (−8.797) | −0.058 *** (−8.875) |

| PPE | 0.048 *** (3.336) | 0.065 *** (4.433) |

| LEV | −0.100 *** (−10.622) | −0.128 *** (−13.406) |

| ALTMAN | 0.001 *** (5.826) | 0.001 *** (5.718) |

| DCFO | 0.003 (0.506) | 0.001 (0.181) |

| DCFO × CFO | 0.075 (1.373) | 0.213 *** (4.183) |

| DELIST | −0.122 *** (−8.088) | |

| DELIST × CFO | 0.434 *** (2.800) | |

| DELIST × DCFO | −0.059 *** (−2.969) | |

| DELIST × DCFO × CFO | −0.081 (−0.455) | |

| BIG4 | 0.010 *** (2.978) | |

| DELIST × BIG4 × CFO | 0.315 * (1.742) | |

| DELIST × BIG4 × DCFO | 0.016 (0.555) | |

| DELIST × BIG4 × CFO × DCFO | −0.739 ** (−2.569) | |

| SUBST | −0.085 *** (−2.682) | |

| SUBST × CFO | −0.313 (−0.905) | |

| SUBST × DCF0 | −0.123 *** (−3.142) | |

| SUBST × CFO × DCFO | 0.612 * (1.648) | |

| ∑IND | included | |

| ∑YEAR | included | |

| F-stat. (Adjusted R-Square) | 39.265 *** (21.34%) | 31.939 *** (16.66%) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shawn, H.; Kim, Y.-w.; Jung, J.-g. Company’s Sustainability and Accounting Conservatism: Firms Delisting from KOSDAQ. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061775

Shawn H, Kim Y-w, Jung J-g. Company’s Sustainability and Accounting Conservatism: Firms Delisting from KOSDAQ. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061775

Chicago/Turabian StyleShawn, Hyuk, Yun-wha Kim, and Jae-gyung Jung. 2019. "Company’s Sustainability and Accounting Conservatism: Firms Delisting from KOSDAQ" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061775

APA StyleShawn, H., Kim, Y.-w., & Jung, J.-g. (2019). Company’s Sustainability and Accounting Conservatism: Firms Delisting from KOSDAQ. Sustainability, 11(6), 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061775