Internal and External Influential Factors on Waste Disposal Behavior in Public Open Spaces in Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

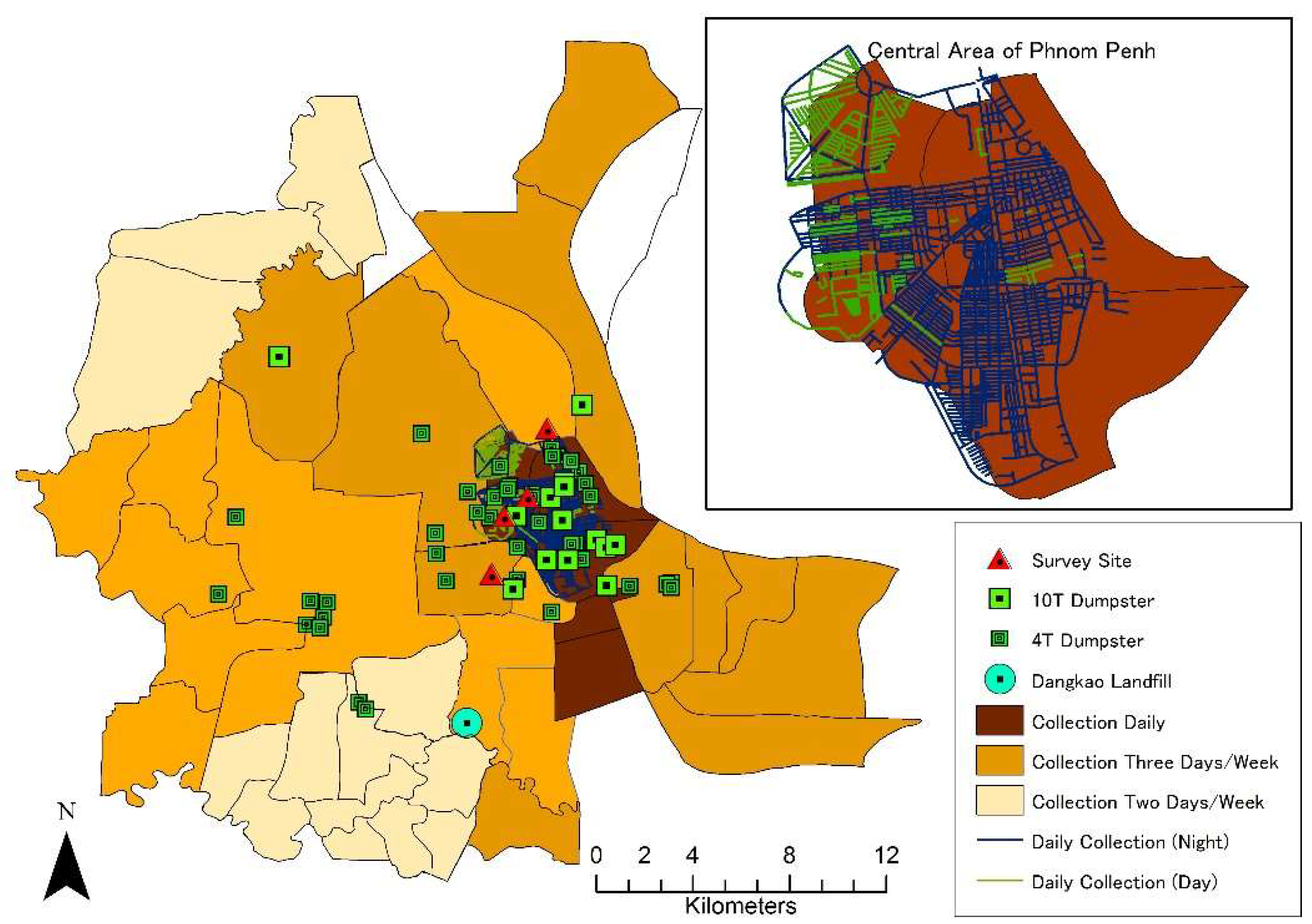

2.1. Study Area

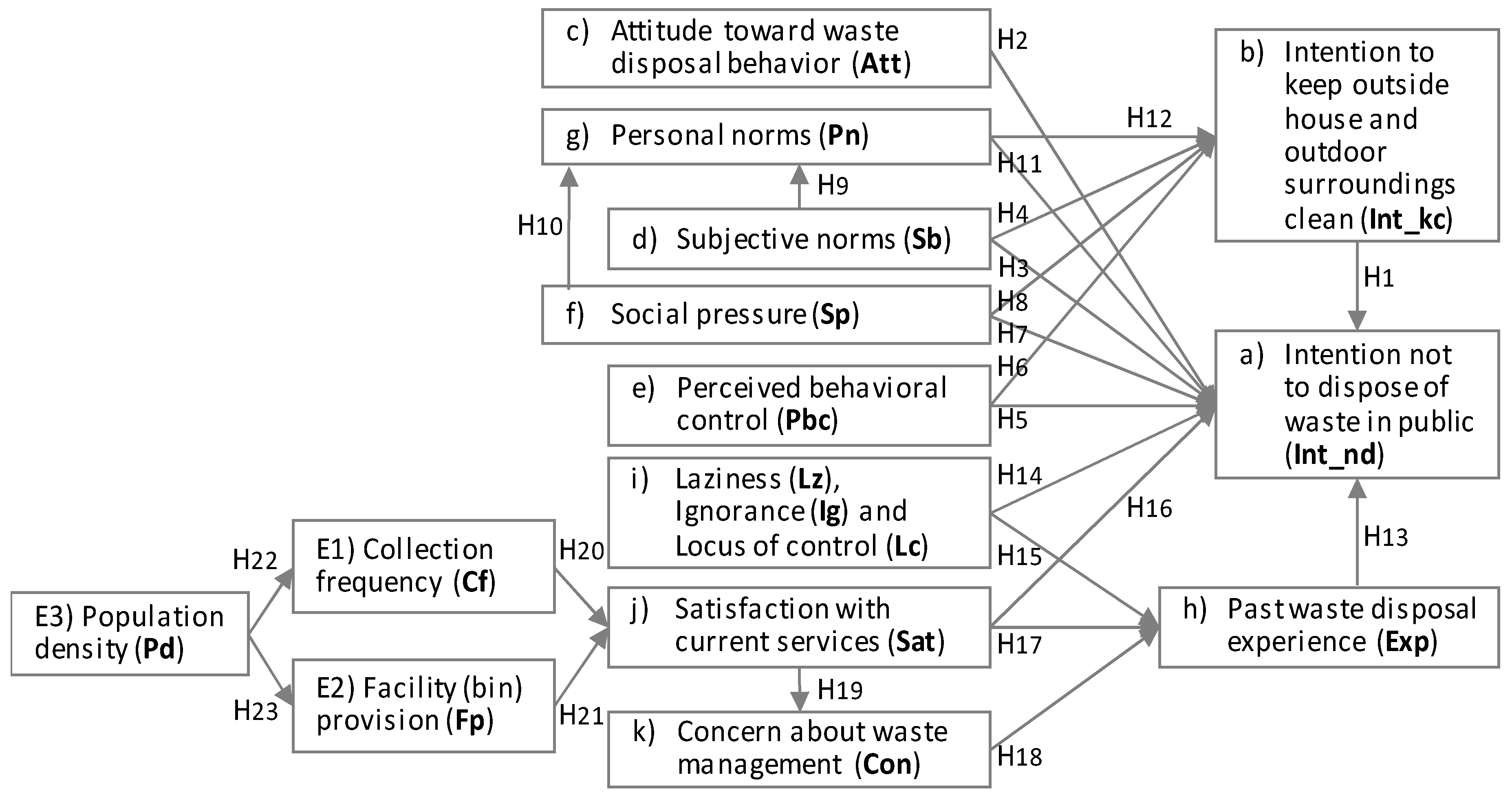

2.2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.3. Questionnaire Design

2.4. Questionnaire Survey

2.5. Analytical Method

3. Results

3.1. Sample Distribution

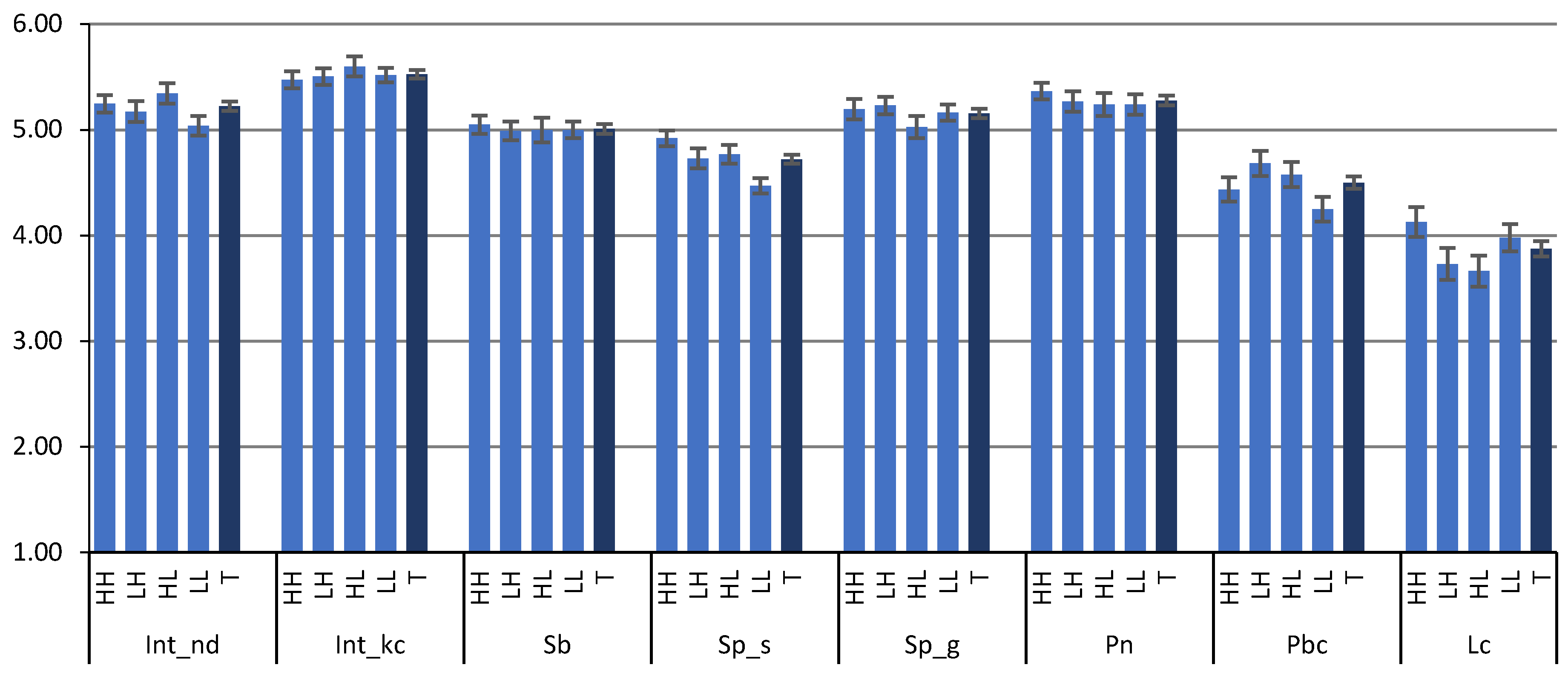

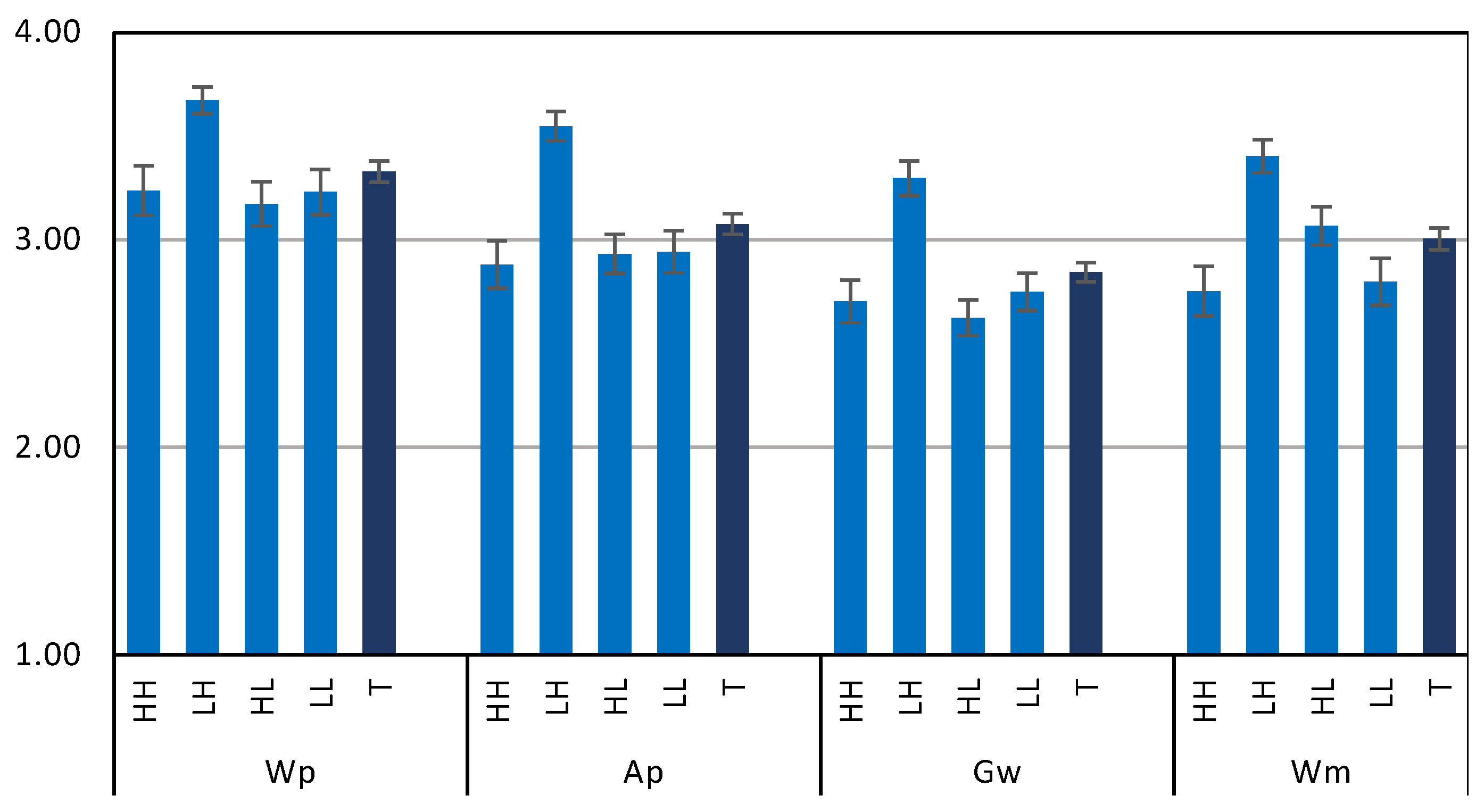

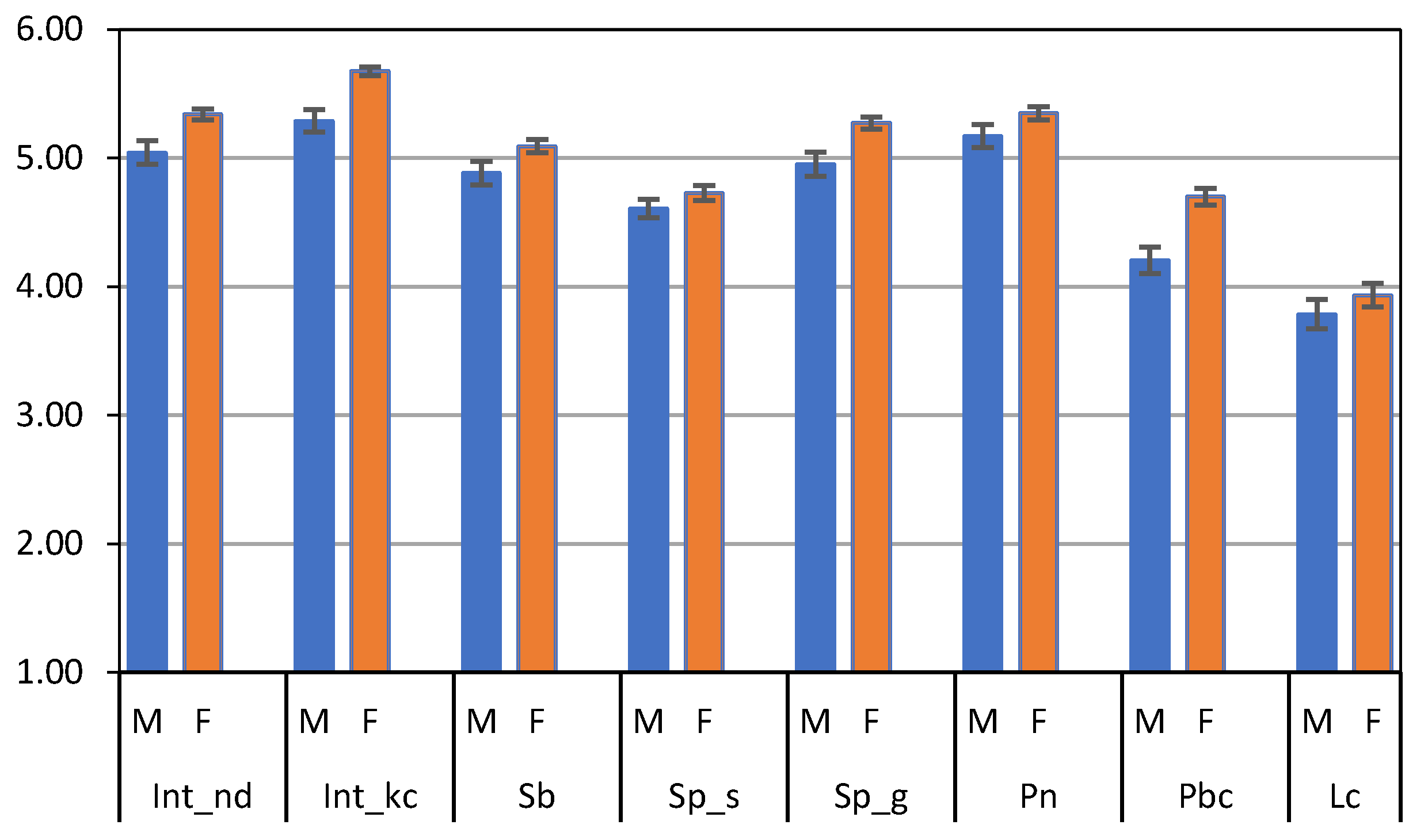

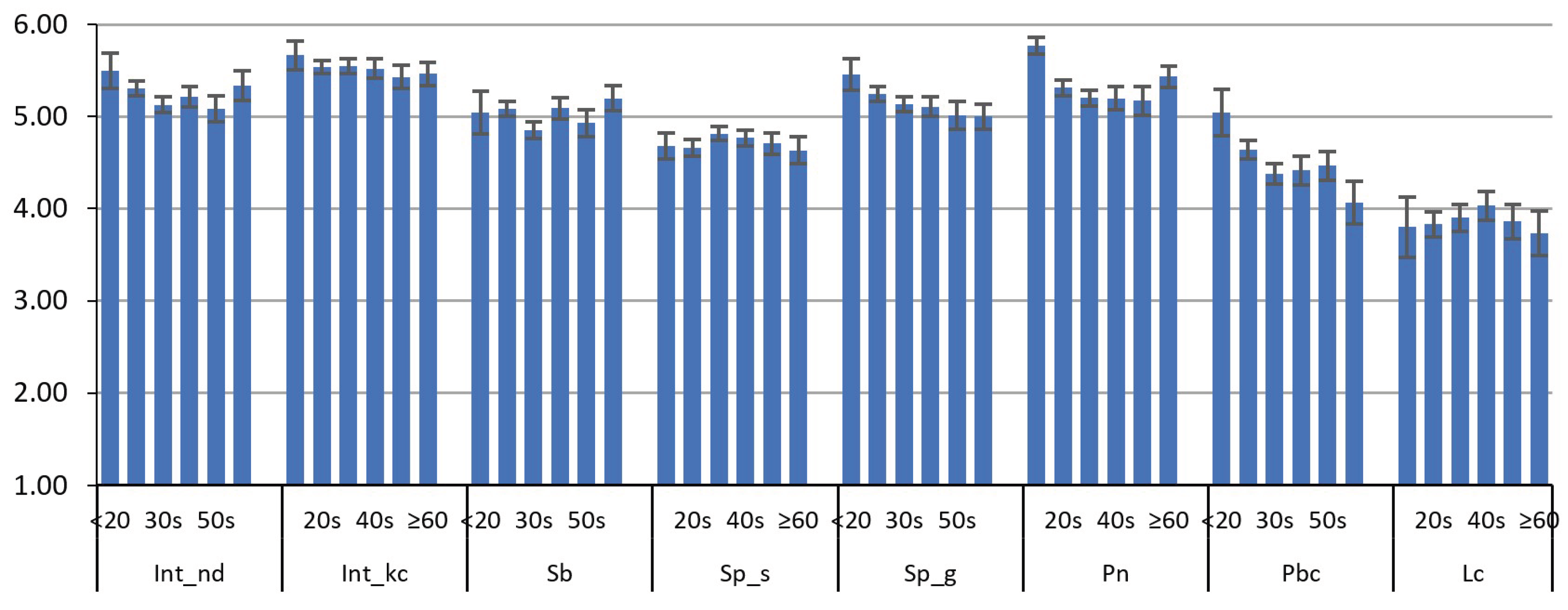

3.2. Summary of Obtained Data

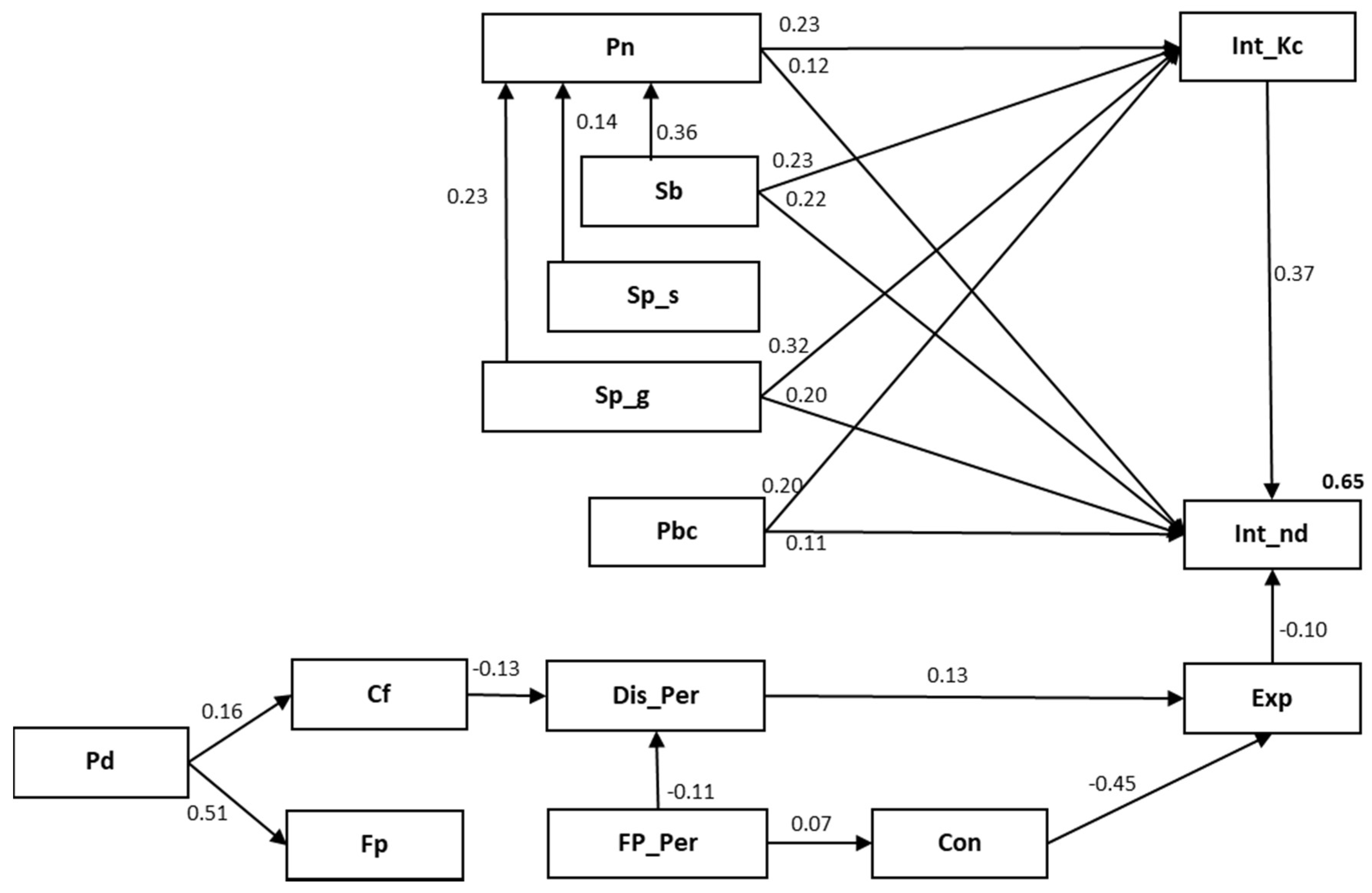

3.3. Model Estimation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kum, V.; Sharp, A.; Harnpornchai, N. Improving the solid waste management in Phnom Penh city: A strategic approach. Waste Manag. 2005, 25, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seng, B.; Kaneko, H.; Hirayama, K.; Katayama-Hirayama, K. Municipal solid waste management in Phnom Penh, capital city of Cambodia. Waste Manag. 2010, 29, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojedokun, O. Attitude towards littering as a mediator of the relationship between personality attributes and responsible environmental behavior. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2601–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thondhlana, G.; Hlatshwayo, T.N. Pro-environmental behavior in student residences at Rhodes University, South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Hung, R.J.; Lee, C.H.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Determinants of residents’ E-waste recycling behavioral intention: A case study from Vietnam. Sustainability 2019, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. External influences on forming residents’ waste separation behaviour: Evidence from households in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conke, L.S. Barriers to waste recycling development: Evidence from Brazil. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskamp, S.; Harrington, M.J.; Edwards, T.C.; Sherwood, D.L.; Okuda, S.M.; Swanson, D.C. Factors influencing household recycling behavior. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as altruistic behavior: Normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, G. Altruistic, egoistic, and normative effects on curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 733–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Foxall, G.R.; Pallister, J. Beyond the intention–behaviour mythology: An integrated model of recycling. Mark. Theory 2002, 2, 29–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, C.; Hernández, B.; Cuadrado, E.; Luque, B.; Pereira, C.R. A multilevel perspective to explain recycling behaviour in communities. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 159, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.-F.; Malesios, C. Extending the theory of planned behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, W. Applying the theory of planned behavior to recycling behavior in South Africa. Recycling 3.3 2018, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, J.; Cherian, J.; Madansky, M.; Narayana, C. Determinants of recycling behavior: A synthesis of research results. J. Socio Econ. 1995, 24, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Strategies for sustainability: Citizens and responsible environmental behaviour. Area 2003, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeva, K.; Alriksson, S. Influence of recycling programmes on waste separation behaviour. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Bator, R.J.; Large, L.B.; Bruni, C.M.; Tabanico, J.J. Littering in context: Personal and environmental predictors of littering behavior. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib, I.A.; Arafat, H.A.; Daoud, R.; Shwahneh, H. Enhanced solid waste management by understanding the effects of gender, income, marital status, and religious convictions on attitudes and practices related to street littering in Nablus—Palestinian territory. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintri. Waste Collection Reports for Khan Dongkor, Khan Prampir Meakkakra, Khan Chbar Amporv, Khan Chhroy Chongva, Khan Chomkar Mom, Khan Duon Penh, Khan Mean Chey, Khan Pousenchey, Khan Prek Pnov, Khan Reussey Keo District, Khan Sensok, and Khan Tuol Kork. 2016. Available online: http://www.cintri.com.kh/view.aspx?LID=KH&mID=H11 (accessed on 10 March 2019). (In Khmer).

- National Institute of Statistics of Cambodia (NIS). General Population Census of Cambodia 2008; National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2009.

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Levine, T.R.; Sharkey, W.F. The theory of reasoned action and self-construals: Understanding recycling in Hawaii. Commun. Stud. 2009, 49, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B. A moral basis for recycling: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arı, E.; Yılmaz, V. A proposed structural model for housewives’ recycling behavior: A case study from Turkey. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 129, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X. Determinants of residents’ e-waste recycling behaviour intentions: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoleto, A.P.; Kurisu, K.H.; Hanaki, K. Model development for household waste prevention behaviour. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, P.; Douglas, P. WR0112: Understanding Household Waste Prevention Behaviour; Technical Report 2007 No. 3: A Conceptual and Operational Model of Household Waste Prevention Behaviour; Defra: London, UK, 2018. Available online: http://randd.defra.org.uk (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative explanations for helping behavior: A critique, proposal, and empirical test. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 9, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J. Norms for environmentally responsible behaviour: An extended taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N.J. A conceptual framework for understanding and analysing attitudes towards household-waste management. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 2025–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.T.; Fang, W.T.; Kaplan, U.; Ng, E. Locus of control: The mediation effect between emotional stability and pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojedokun, O.; Balogun, S.K. Psycho-sociocultural analysis of attitude towards littering in a Nigerian urban city. Ethiopian J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2011, 4, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the theory of planned behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, J.C. Latent Variables Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, T. Statistics, an Introductory Analysis, 2nd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics of Cambodia (NIS). National Socio-Economic Census; National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2015.

- Matthies, E.; Selge, S.; Klöckner, C.A. The role of parental behaviour for the development of behaviour specific environmental norms—The example of recycling and re-use behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C. The impact of norms and assumed consequences on recycling behavior. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 630–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Explaining proenvironmental intention and behavior by personal norms and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. A model of recycling behaviour, with evidence from Danish source separation programs. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1994, 11, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.M.; Smith, J.R.; Terry, D.J.; Greenslade, J.H.; McKimmie, B.M. Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, T.; Zampetakis, L.A.; Lasaridi, K. Psychological determinants of household recycling intention in the context of the theory of planned behaviour. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 2013, 22, 2035–2041. [Google Scholar]

| Commune | Collection Frequency (Times/Week) | Population Density (pop/km2) | Streets Surveyed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HH | Phsar Depou Ti Pir | High | 7 | High | 53,700 | St. 134, 138, 146, 221, 225, 233 |

| LH | Tuol Sangka | Low | 3 | High | 19,060 | St. 103, 105, 273, 518, 590 |

| HL | Toek Laak I | High | 7 | Low | 14,858 | St. 132, 138, 261, 265 |

| LL | Steung Mean Chey | Low | 3 | Low | 7864 | St. 23, 38, 62, 217, 371 |

| Item | Category | Sample (%) | Cambodia Average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 413) | Urban | Rural | |||||

| HH* (n = 101) | LH* (n = 104) | HL* (n = 104) | LL* (n = 104) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 39.7 | 40.6 | 46.2 | 32.7 | 39.4 | 48.64 [41] |

| Female | 60.3 | 59.4 | 53.8 | 67.3 | 60.6 | 51.36 [41] | |

| Age | <20 | 5.3 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 1.9 | 34.8 [22] |

| 20s | 31.2 | 23.8 | 50.0 | 35.6 | 15.4 | 19.4 [22] | |

| 30s | 26.5 | 36.6 | 14.4 | 26.9 | 27.9 | 11.5 [22] | |

| 40s | 15.8 | 19.8 | 13.5 | 12.5 | 17.3 | 10.3 [22] | |

| 50s | 13.8 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 8.7 | 26.9 | 6.6 [22] | |

| ≥60 | 7.5 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 17.4 [22] | |

| Education level | Uneducated | 6.0 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 10.6 | 20.7 [41] |

| Primary school | 19.8 | 18.8 | 16.3 | 11.5 | 32.7 | 57.9 [41] | |

| Secondary school | 18.8 | 7.9 | 15.4 | 24.0 | 27.9 | 11.4 [41] | |

| High school | 22.5 | 21.8 | 11.5 | 34.6 | 22.1 | 5.3 [41] | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 31.8 | 43.6 | 51.9 | 25.0 | 6.7 | 4.7 [41] | |

| Master’s degree | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Doctorate | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Monthly family income | <200 USD | 26.4 | 19.8 | 37.5 | 18.3 | 29.8 | About 400 USD [41] |

| 200–500 USD | 43.1 | 37.6 | 29.8 | 53.8 | 51.0 | ||

| 500–800 USD | 19.9 | 27.7 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 14.4 | ||

| >800 USD | 10.7 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 8.7 | 4.8 | ||

| Cars owned | None | 80.1 | 70.3 | 84.6 | 78.8 | 86.5 | None: 96% [41] |

| 1 | 16.0 | 21.8 | 11.5 | 19.2 | 11.5 | ||

| 2 | 3.7 | 7.9 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 1.9 | ||

| 3 or more | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Motorbikes owned | None | 7.3 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 8.7 | None: 36% [41] |

| 1 | 36.3 | 36.6 | 28.8 | 38.5 | 41.3 | ||

| 2 | 30.1 | 31.7 | 31.7 | 28.8 | 28.3 | ||

| 3 or more | 23.0 | 21.8 | 33.7 | 27.9 | 8.7 | ||

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int_nd | Int_kc | ||||||

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | ||

| (b) | Int_kc | 0.37 | - | 0.37 | |||

| (d) | Sb | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| (e) | Pbc | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.20 | - | 0.20 |

| (f-1) | Sp_s | - | 0.03 | 0.03 | - | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| (f-2) | Sp_g | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.31 |

| (g) | Pn | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.23 | - | 0.23 |

| (h) | Exp | −0.10 | - | −0.10 | - | - | - |

| (k) | Con | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| (l-1) | Dis_per | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.04 | - | −0.07 | −0.07 |

| (l-2) | Fp_per | - | 0.01 | 0.01 | - | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (E1) | Fp | - | −0.01 | −0.01 | - | - | - |

| (E2) | Cf | - | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0. | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (E3) | Pd | - | −0.01 | −0.01 | - | −0.01 | −0.01 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srun, P.; Kurisu, K. Internal and External Influential Factors on Waste Disposal Behavior in Public Open Spaces in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061518

Srun P, Kurisu K. Internal and External Influential Factors on Waste Disposal Behavior in Public Open Spaces in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061518

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrun, Pagnarith, and Kiyo Kurisu. 2019. "Internal and External Influential Factors on Waste Disposal Behavior in Public Open Spaces in Phnom Penh, Cambodia" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061518

APA StyleSrun, P., & Kurisu, K. (2019). Internal and External Influential Factors on Waste Disposal Behavior in Public Open Spaces in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Sustainability, 11(6), 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061518