Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Foods with Traceability Information: Ex-Ante Quality Assurance or Ex-Post Traceability?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

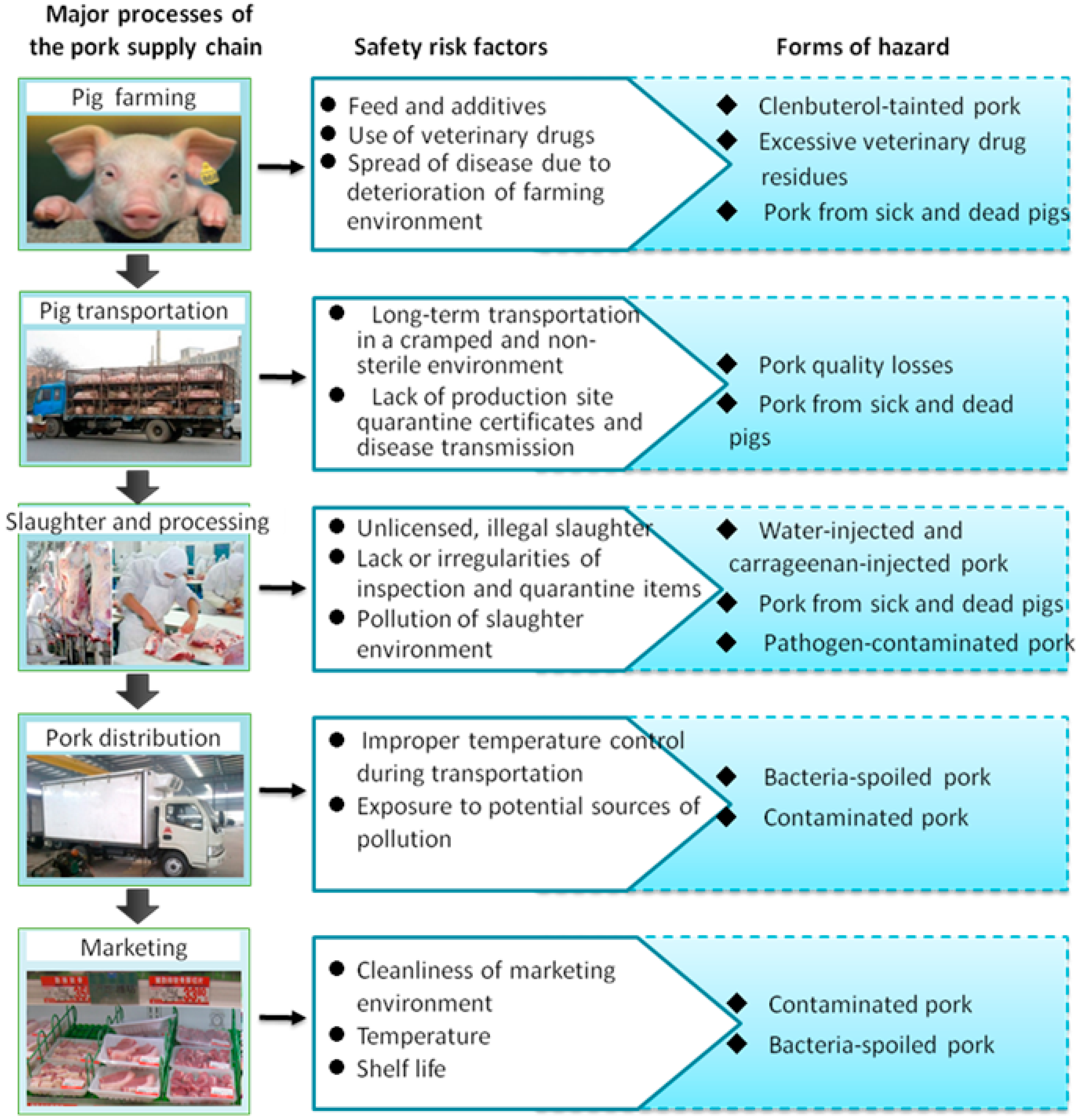

3.1. Selection of Food Type

3.2. Information Attributes

3.3. Selection of Experimental Method

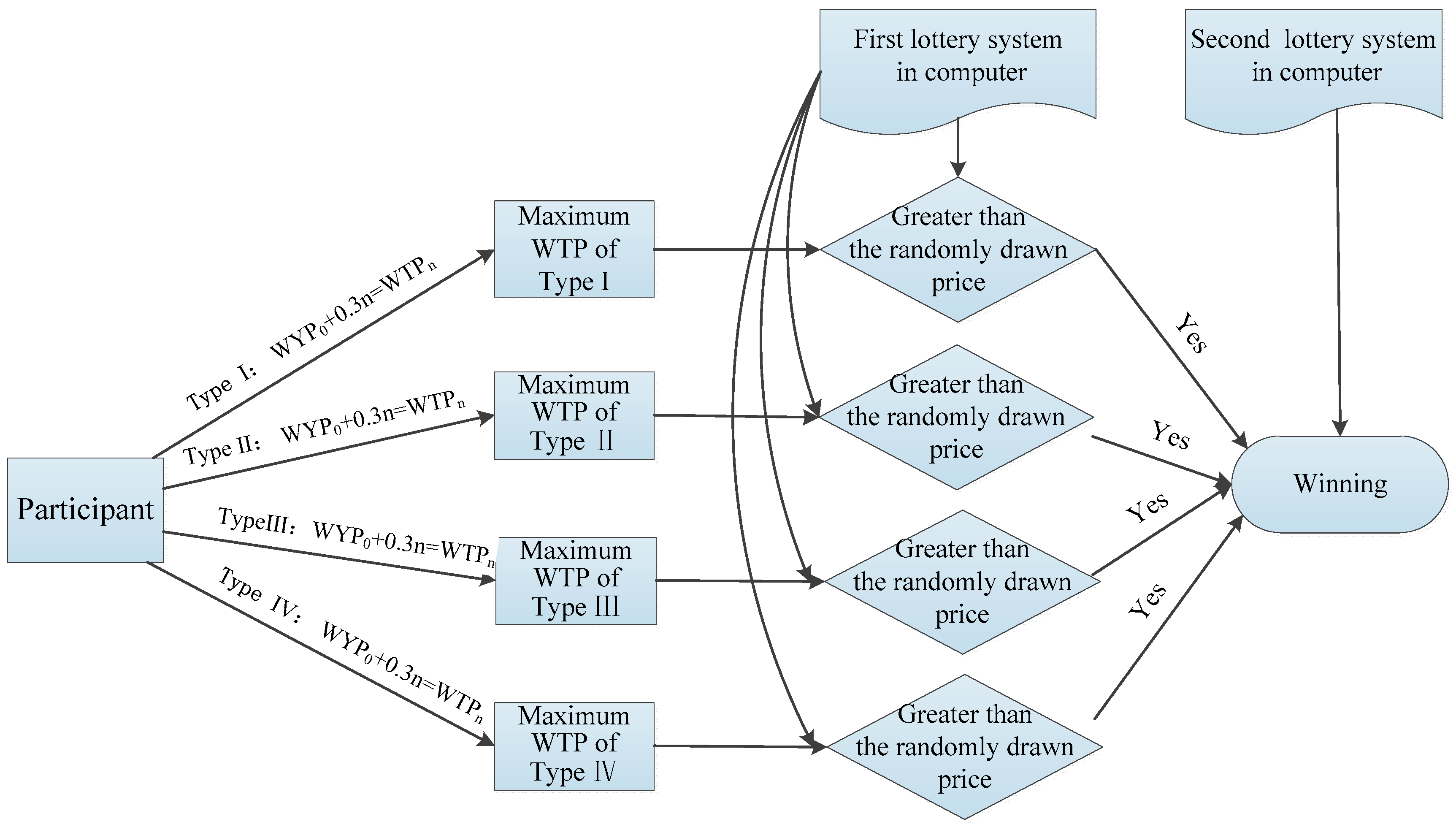

3.4. Preparation and Procedure of Experimental Auction

3.5. Implementation of Experiment Auction

3.6. Statistical Analysis of Participants

3.7. Consumer Bids in the Experiment Auction

4. Research Framework, Econometric Model and Analysis Results

4.1. Model Selection and Variable Setting

4.2. Results and Discussion

5. Main Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Traceability in a food supply chain: Safety and quality perspectives. Food Control 2014, 39, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kher, S.V.; Frewer, L.J.; Jonge, J.D.; Wentholt, M.; Davies, O.H.; Luijckx, N.B.L. Experts’ perspectives on the implementation of traceability in Europe. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, B.; Gooch, M.; Dent, B.; Marenick, N.; Miller, A.; Sylvia, G. Assessing the Value and Role of Seafood Traceability from an Entire Value-Chain Perspective. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 3, 205–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzuti, T.; Mirabelli, G. The Global Track &Trace System for food: General framework and functioning principle. J. Food Eng. 2015, 159, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, J.E.; Bailey, D.V.; Dickinson, D.L. Traceability in the Canadian Red Meat Sector: Do Consumers Care. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 1, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Wang, S.X.; Xu, L.L. Consumer demand for traceable food: The case of traceable pork. J. Public Manag. 2013, 3, 119–128. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.H.; Wang, S.X.; Zhu, D.; Hu, W.Y.; Wang, H.S. Chinese consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for traceable food quality and safety attributes: The case of pork. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 35, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Wang, H.H.; Widmar, N.J.O. Welfare and Market Impacts of Food Safety Measures in China: Results from Urban Consumers’ Valuation of Product Attributes. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 6, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A New Approach to Consumer Theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 6, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. Advertising as Information. J. Political Econ. 1974, 3, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. Information asymmetry and the role of traceability systems. Agribusiness 2004, 4, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Wang, H.S.; Zhu, D. Analysis of consumer demand for traceable pork in China based on a real choice experiment. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2015, 2, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E.; Sanderson, K.; Haghiri, M. Evaluating willingness-to-pay for bison attributes: An experimental auction approach. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 2, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Ward, R.W. Consumer interest in information cues denoting quality, traceability and origin: An application of ordered probit models to beef labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 6, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J. A choice experiment model for beef: What US consumer responses tell us about relative preferences for food safety, country-of-origin labeling and traceability. Food Policy 2007, 4, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W.Y.; Maynard, L.J.; Goddard, E.U.S. Consumers’ Preference and Willingness to Pay for Country-of-Origin-Labeled Beef Steak and Food Safety Enhancements. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 61, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Feldkamp, T.; Schroeder, T.C. Experimental auction procedure: Impact on valuation of quality differentiated goods. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 2, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Mainville, D.; You, W.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for grass-fed beef: Empirical evidence from in-store experiments. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 7, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Bai, J.; Wahl, T.I. Consumers’ willingness to pay for traceable pork, milk, and cooking oil in Nanjing, China. Food Control 2012, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, J. The role of certificate issuer on consumers’ willingness to pay for milk traceability in China. Agric. Econ. 2013, 4–5, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghiri, M. An evaluation of consumers’ preferences for certified farmed Atlantic salmon. Br. Food J. 2014, 7, 1092–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, A.; Vecchio, R.; Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Cembalo, L. Willingness to pay for insect-based food: The role of information and carrier. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.S.; Zhou, L. Consumer interest in information provided by food traceability systems in Japan. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 36, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Wang, H.S.; Liu, X.L. Traceable pork: Information combination and consumers’ wiliness to pay. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 4, 35–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- De-Magistris, T.; Gracia, A.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. On the use of honesty priming tasks to mitigate hypothetical bias in choice experiments. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 5, 1136–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnevehr, L.; Eales, J.; Jensen, H. Food and Consumer Economic. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 2, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Qin, S.S.; Zhu, D.; Li, Q.G.; Hu, W.Y. Consumer preferences for origin and traceability information of traceable pork. Chin. Rural Econ. 2016, 6, 47–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Reid, L.M.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Downey, G. Recent technological advances for the determination of food authenticity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaichi, F.; Gil, G.M.; Nayga, R.M. Assessing the market potential for a local food product Evidence from a non-hypothetical economic experiment. Br. Food J. 2012, 1, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, L.H.; Wang, S.X. Consumer preference and demand for traceable food attributes. Br. Food J. 2016, 9, 2140–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphonce, R.; Alfnes, F. Eliciting Consumer WTP for Food Characteristics in a Developing Context: Application of Four Valuation Methods in an African Market. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 1, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaichi, F.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Gil, G.M. Assessing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Different Units of Organic Milk: Evidence from Multiunit Auctions. Can. J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 4, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamukwala, P.; Oparinde, A.; Binswanger-Mkhize, H.P. Design Factors Influencing Willingness-to-Pay Estimates in the Becker-DeGroot-Marschak (BDM) Mechanism and the Non-hypothetical Choice Experiment: A Case of Biofortified Maize in Zambia. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 1, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginon, E.C.; Chabanet, P.; Combris, S.I. Are decisions in a real choice experiment consistent with reservation prices elicited with BDM ‘auction’? The case of French baguettes. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drichoutis, A.C.; Lusk, J.L. What can multiple price lists really tell us about risk preferences? J. Risk Uncertain 2016, 53, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamas Csermely, T.; Rabas, A. How to reveal people’s preferences: Comparing time consistency and predictive power of multiple price list risk elicitation methods. J. Risk Uncertain 2016, 53, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, G.M.; Degrooot, M.H.; Marschak, J. Measuring utility by a single response sequential method. Behav. Sci. 1964, 3, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginon, E.P.; Combris, Y.; Lohéac, G.; Enderli, S.I. What do we learn from comparing hedonic scores and willingness-to-pay data? Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 33, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z. Research on Retailer Dynamic Pricing and Procurement Strategy Based on Customer’s Willingness to Pay. Master’s Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.H.; Xu, L.L.; Zhu, D.; Wang, X.L. Factors affecting consumer willingness to pay for certified traceable food in jiangsu province of china. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 3, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, A.M.; Gil, J.M. Risk perception and consumer willingness to pay for certified beef in Spain. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 8, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Beriain, M.J.; Carr, T.R. Socio-economic factors affecting consumer behaviour for United States and Spanish beef under different information scenarios. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 24, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Xu, L.L.; Zhu, D.; Wu, L.H. Consumers’ WTP for certified traceable tea in China. Br. Food J. 2015, 5, 1440–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijenstolpe, C. Evaluating animal welfare with choice experiments: An application to Swedish pig production. Agribusiness 2008, 1, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Vidal, R.; Silva, R.; Vallejos, L.; Sepulveda, N. Consumer willingness to pay for beef meat in a developing country: The effect of information regarding country of origin, price and animal handling prior to slaughter. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilava, D.; Foster, K.A.; Lusk, J.L.; Nilsson, T. Effects of income and social awareness on consumer WTP for social product attributes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 4, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huo, X. Willingness-to-pay price premiums for certified fruits—A case of fresh apples in China. Food Control 2016, 64, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function | Attribute | Type | Explanation Given to Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ex-ante quality assurance | Pork quality inspection | Type I Labeling as acceptable | Labeling products as acceptable after testing of physical and chemical indicators, such as pesticide and veterinary drug residues and microbial indicators, such as number of Escherichia coli, by a qualified testing agency. |

| Quality management system certification | Type II Labeling as certified | Labeling slaughtering and processing enterprises with a mark of quality management system certification after review of quality and safety management capability by a qualified certification agency. | |

| Ex-post traceability | Supply chain traceability | Type III Labeling with a traceability barcode | Scanning Type III barcode through a public inquiry platform, consumers can obtain the basic information about enterprise in the pork supply chain |

| Supply chain-and-internal traceability | Type IV Labeling with a traceability barcode | Scanning Type IV barcode through a public inquiry platform, consumers can obtain information about what type III has, as well as critical internal safety records such as the source of feed, veterinary drug use and inspection |

| Type | Initial Quotations (Yuan) | Final Quotations (Yuan) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Mean | Standard Deviation | Max | Min | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Type I | 9.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 2.1 |

| Type II | 8.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 9.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| Type III | 7.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 1.6 |

| Type IV | 8.5 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Group | Mann-Whitney U | Wilcoxon W | Z | Significance | ||||

| Mann-Whitney U test results between mean bids for different information attributes | Pair 1 | Type I–Type II | 26,635.500 | 60,305.500 | −4.064 | 0.000 | ||

| Pair 2 | Type I–Type Ⅲ | 24,791.000 | 58,461.000 | −5.150 | 0.000 | |||

| Pair 3 | Type I–Type Ⅳ | 28,961.500 | 62,631.500 | −2.693 | 0.007 | |||

| Pair 4 | Type II–Type Ⅲ | 30,726.000 | 64,396.000 | −1.656 | 0. 098 | |||

| Pair 5 | Type II–Type Ⅳ | 29,768.000 | 63,438.000 | −2.217 | 0.027 | |||

| Pair 6 | Type Ⅲ–Type Ⅳ | 29,020.500 | 62,690.500 | −2.661 | 0.008 | |||

| Variable | Definition | Expected Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Bid for type I safety information (Y1) | Continuous variable; the final WTP price (that is maximum WTP) gained from the MPL. | —— |

| Bid for type II safety information (Y2) | Continuous variable; the final WTP price (that is maximum WTP) gained from the MPL. | —— |

| Bid for type III safety information (Y3) | Continuous variable; the final WTP price (that is maximum WTP) gained from the MPL. | —— |

| Bid for type IV safety information (Y4) | Continuous variable; the final WTP price (that is maximum WTP) gained from the MPL. | —— |

| Low age (X1) | Dummy variable; 40 years of age or younger = 1, otherwise = 0 | + |

| High age (X2) | Dummy variable; 60 years of age or older = 1, otherwise = 0 | − |

| Low education (X3) | Dummy variable; junior high school and lower education = 1, otherwise = 0 | − |

| High education (X4) | Dummy variable; university and higher education = 1, otherwise = 0 | + |

| Low income (X5) | Dummy variable; monthly income of 2000 yuan and less = 1, otherwise = 0 | − |

| High income (X6) | Dummy variable; monthly income of 8000 yuan and more = 1, otherwise = 0 | + |

| History of foodborne disease due to consumption of unsafe pork (X7) | Dummy variable; yes = 1, no = 0 | + |

| Perceived harm caused by unsafe pork (X8) | Very great = 1; great = 2; moderate = 3; small = 4; no harm = 5 | + |

| Concern about food safety (X9) | Very concerned = 1; somewhat concerned = 2; moderately concerned = 3; not very concerned = 4; not concerned at all = 5 | + |

| Satisfaction with food safety (X10) | A score of 0 to 10 was assigned according to the level of satisfaction | − |

| Confidence in food safety labeling (X11) | Highly confident = 1; fairly confident = 2; moderately confident = 3; not very confident = 4; not confident at all = 5 | + |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I 1 | Type II 2 | Type III 3 | Type IV 4 | |

| Low age | 0.019 (0.259) | 0.175 (0.255) | 0.442 ** (0.207) | 0.465 ** (0.234) |

| High age | −0.786 *** (0.299) | −0.355 (0.296) | −0.210 (0.240) | 0.069 (0.271) |

| Low education | −0.523 ** (0.260) | −0.593 ** (0.256) | −0.894 *** (0.207) | −0.892 *** (0.234) |

| High education | 2.169 *** (0.262) | 1.637 *** (0.258) | 0.774 *** (0.209) | 0.966 *** (0.237) |

| Low income | −1.170 *** (0.380) | −1.159 *** (0.377) | −0.943 *** (0.305) | −1.083 *** (0.344) |

| High income | 0. 499 ** (0.228) | 0.566 ** (0.225) | 0.540 *** (0.182) | 0.744 *** (0.206) |

| History of foodborne disease due to consumption of unsafe pork | 0.046 (0.218) | −0.404 * (0.214) | −0.213 (0.174) | −0.217 (0.196) |

| Perceived harm caused by unsafe pork | −0.267 (0.167) | −0.167 (0.165) | −0.185 (0.134) | −0.230 (0.151) |

| Concern about food safety | −0.023 (0.126) | 0.390 *** (0.124) | 0.164 (0.101) | 0.123 (0.114) |

| Satisfaction with food safety | 0.074 (0.047) | 0.092 ** (0.046) | 0.113 *** (0.038) | 0.094 ** (0.043) |

| Confidence in food safety labeling | −0.063 (0.126) | −0.190 (0.124) | 0.306 *** (0.101) | 0.113 (0.114) |

| Constant term | 3.675 *** (0.722) | 1.408 ** (0.710) | 1.497 ** (0.577) | 2.370 *** (0.652) |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx (Type I) | dy/dx (Type II) | dy/dx (Type III) | dy/dx (Type IV) | |

| Low age | 0.017 | 0.149 | 0.395 ** | 0.419 ** |

| High age | −0.705 *** | −0.302 | −0.187 | 0.062 |

| Low education | −0.469 ** | −0.503 ** | −0.798 *** | −0.803 *** |

| High education | 1.943 *** | 1.390 *** | 0.691 *** | 0.870 *** |

| Low income | −1.049 *** | −0.983 *** | −0.842 *** | −0.975 *** |

| High income | 0. 448 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.482 *** | 0.670 *** |

| History of foodborne disease due to consumption of unsafe pork | 0.041 | −0.343 * | −0.190 | −0.195 |

| Perceived harm caused by unsafe pork | −0.239 | −0.142 | −0.165 | −0.207 |

| Concern about food safety | −0.021 | 0.331 *** | 0.147 | 0.111 |

| Satisfaction with food safety | 0.066 | 0.780 ** | 0.101 *** | 0.085 ** |

| Confidence in food safety labeling | −0.056 | −0.161 | 0.273 *** | 0.102 |

| Constant term | 3.891 *** | 3.144 ** | 2.937 ** | 3.363 *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, B.; Wu, L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, D.; Ying, R.; Tsai, F.-S. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Foods with Traceability Information: Ex-Ante Quality Assurance or Ex-Post Traceability? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051464

Hou B, Wu L, Chen X, Zhu D, Ying R, Tsai F-S. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Foods with Traceability Information: Ex-Ante Quality Assurance or Ex-Post Traceability? Sustainability. 2019; 11(5):1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051464

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Bo, Linhai Wu, Xiujuan Chen, Dian Zhu, Ruiyao Ying, and Fu-Sheng Tsai. 2019. "Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Foods with Traceability Information: Ex-Ante Quality Assurance or Ex-Post Traceability?" Sustainability 11, no. 5: 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051464

APA StyleHou, B., Wu, L., Chen, X., Zhu, D., Ying, R., & Tsai, F.-S. (2019). Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Foods with Traceability Information: Ex-Ante Quality Assurance or Ex-Post Traceability? Sustainability, 11(5), 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051464