Design for Sustainability: The Effect of Lettering Case on Environmental Concern from a Green Advertising Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Green Advertising and Sustainability

2.2. Lettering Case, Arousal, and Congruence

2.3. Congruence, Arousal, and Environmental Concern

2.4. Summerised Literature and Hypotheses

3. Research Method

3.1. Experiment Design and Stimuli

3.2. Subject and Procedure

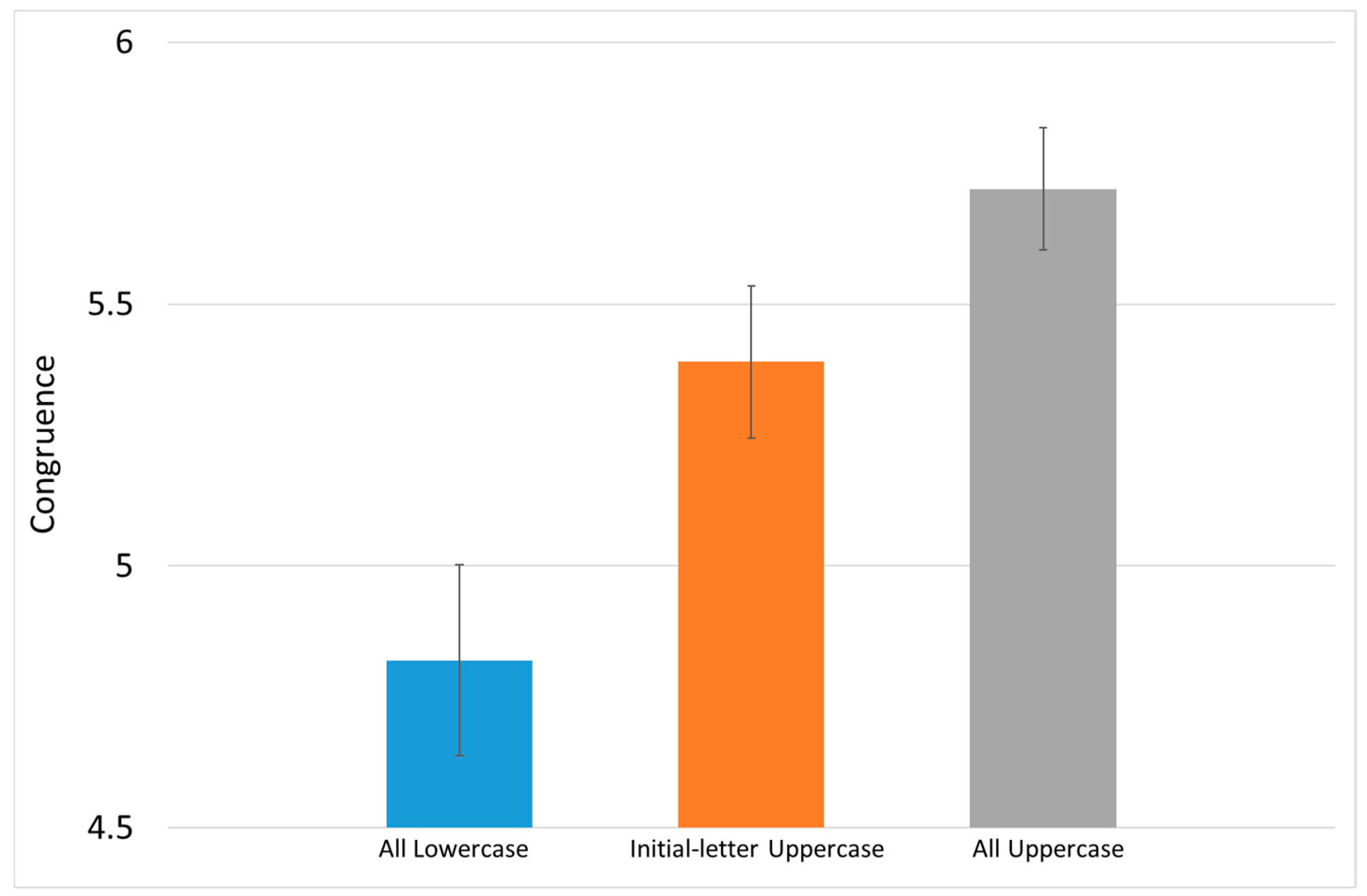

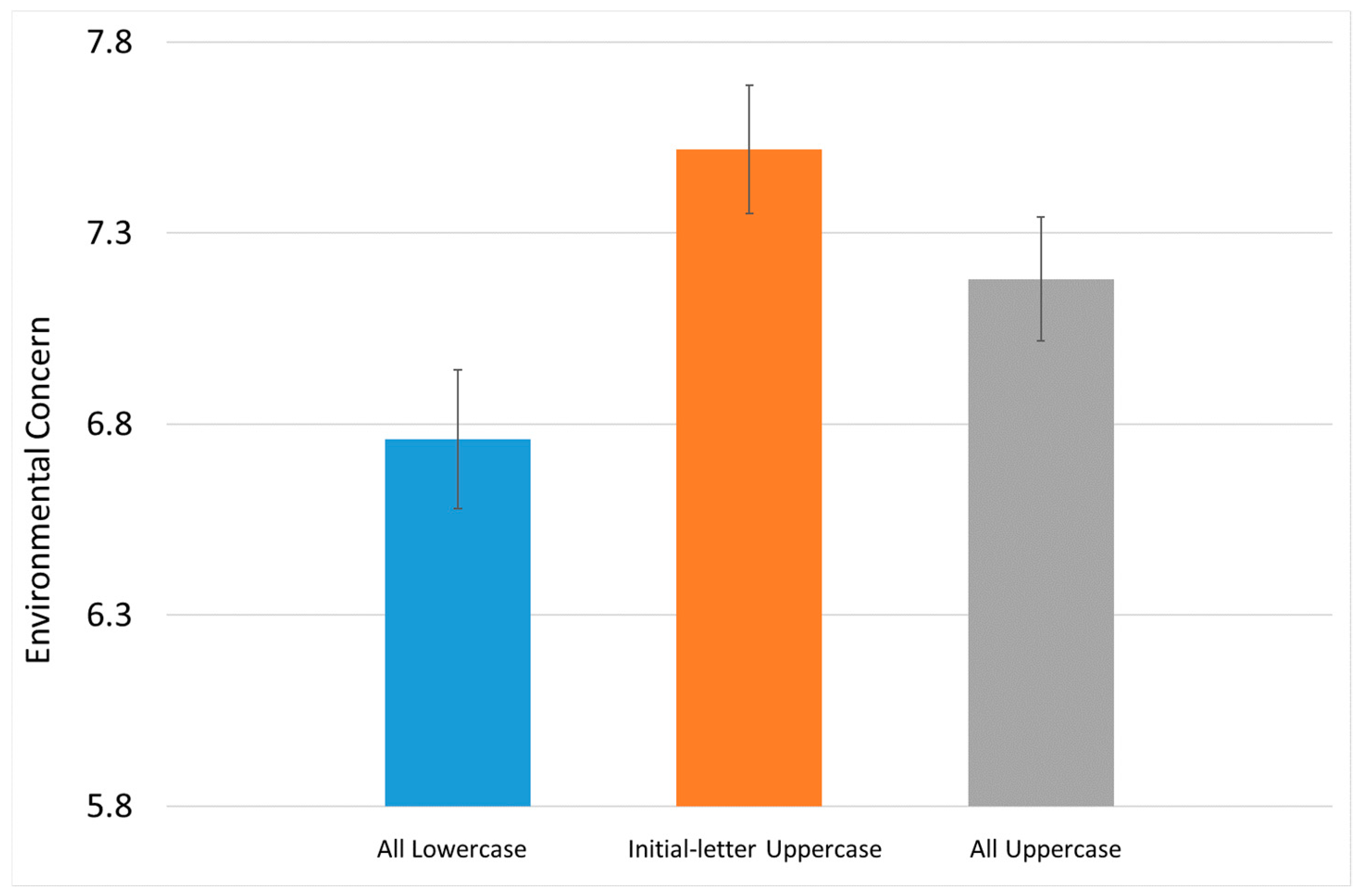

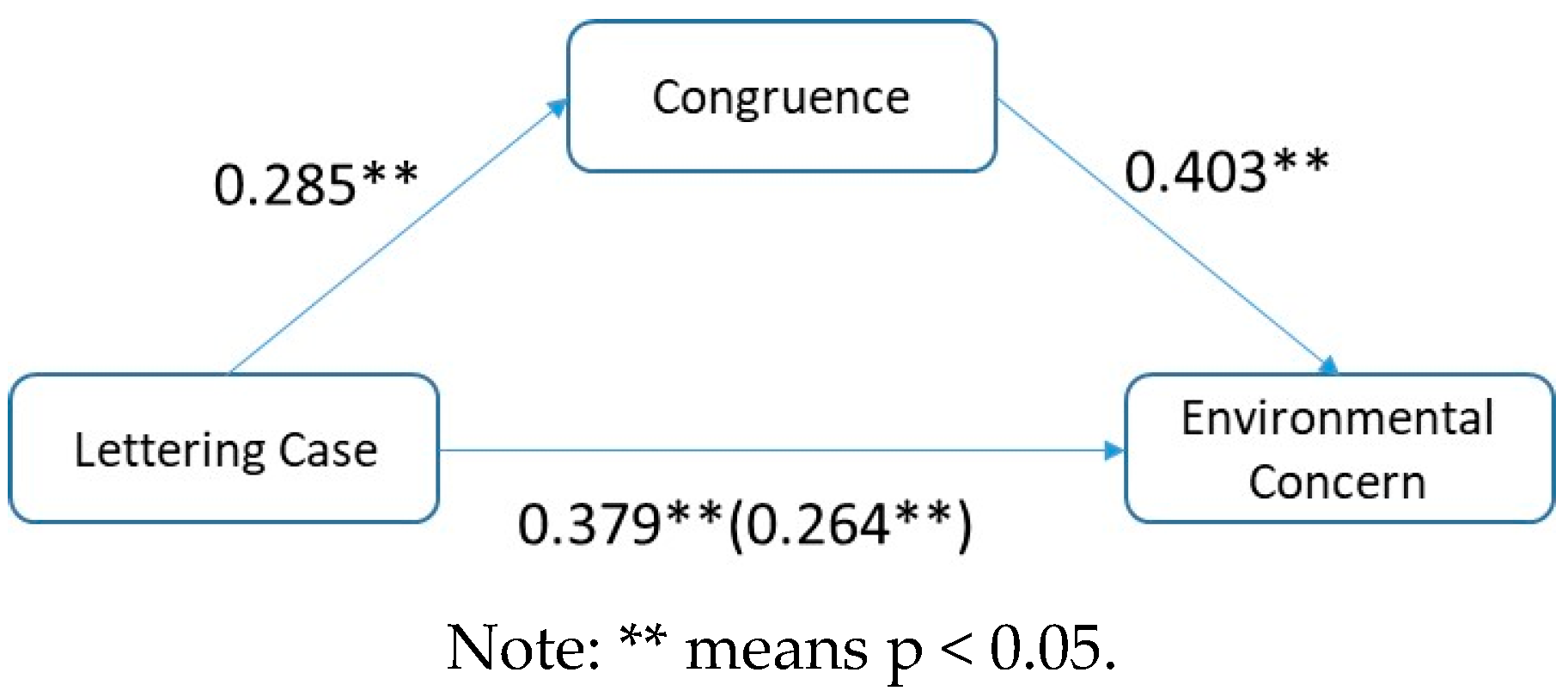

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Conclusions and Discussion

6. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haytko, D.; Matulich, E. Green advertising and environmentally responsible consumer behaviors: Linkages examined. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2008, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Royne, M.B.; Martinez, J.; Oakley, J.; Fox, A.K. The Effectiveness of Benefit Type and Price Endings in Green Advertising. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V.; D’Souza, C.; Barrutia, J.M.; Echebarria, C. Environmental threat appeals in green advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2014, 33, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Endangered Species Conservation|World Wildlife Fund. Available online: https://www.worldwildlife.org/ (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Shin, S.; Ki, E.-J.; Griffin, W.G. The effectiveness of fear appeals in “green” advertising: An analysis of creative, consumer, and source variables. J. Mark. Commun. 2017, 23, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Muralidharan, S. A Green Picture is Worth A Thousand Words?: Effects of Visual and Textual Environmental Appeals in Advertising and the Moderating Role of Product Involvement. J. Promot. Manag. 2015, 21, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeals: Implications for Effective Public Health Campaigns. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, L.K.; Mathur, I. The Effect of Advertising Slogan Changes on the Market Values of Firms. J. Advert. Res. 1995, 35, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Chen, R.; Liu, M.W. The effects of uppercase and lowercase wordmarks on brand perceptions. Mark. Lett. 2017, 28, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, M.; Jiménez, M.; Talero, F.; López-Cañada, S. Letter-case information and the identification of brand names. Br. J. Psychol. 2015, 106, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesbitt, A. The History and Technique of Lettering, 1st ed.; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1957; ISBN 0486204278. [Google Scholar]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived Greenwashing: The Interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental Performance on Consumer Reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Palihawadana, D.; Hultman, M. Evaluating the green advertising practices of international firms: A trend analysis. Int. Mark. Rev. 2011, 28, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Indices Homepage. Available online: https://www.sustainability-indices.com/ (accessed on 14 December 2018).

- Sustainability Index|AIChE. Available online: https://www.aiche.org/ifs/resources/sustainability-index (accessed on 14 December 2018).

- Butlin, J. Our common future. By World commission on environment and development. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 1, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J. Making Sustainability Work; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781351280129. [Google Scholar]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond ecolabels: What green marketing can learn from conventional marketing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A. The Skeptical Green Consumer Revisited: Testing the Relationship Between Green Consumerism and Skepticism Toward Advertising. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.M.F.; Reis, R. Factors Affecting Skepticism toward Green Advertising. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabzdylova, B.; Raffensperger, J.F.; Castka, P. Sustainability in the New Zealand wine industry: Drivers, stakeholders and practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.; Grove, S.J.; Kangun, N.; Polonsky, M.J. An International Comparison of Environmental Advertising: Substantive versus Associative Claims. J. Macromark. 1996, 16, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R.; Kabanoff, B. Computer-aided content analysis: What do 240 advertising slogans have in common? Mark. Lett. 1996, 7, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimofte, C.V.; Yalch, R.F. Consumer Response to Polysemous Brand Slogans. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 33, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlén, M.; Rosengren, S. Brands affect slogans affect brands? Competitive interference, brand equity and the brand-slogan link. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, S.; Dahlén, M. Brand–Slogan Matching in a Cluttered Environment. J. Mark. Commun. 2006, 12, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalch, R.F. Memory in a jingle jungle: Music as a mnemonic device in communicating advertising slogans. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rompay, T. Symbolic Meaning Integration in Design and Its Influence on Product and Brand Evaluation; MinD-Designing for People with Dementia View Project PhD Project on the Experience of Hospitality-Communication Studies; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherland, 2009; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, C.; Leuthesser, L.; Suri, R. Got slogan? Guidelines for creating effective slogans. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, P.; Sacristán, M.; Baño, A.; Fernández, E. Persuasion and advertising English: Metadiscourse in slogans and headlines. J. Pragmat. 2001, 33, 1291–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mulken, M.; van Enschot-van Dijk, R. Puns, relevance and appreciation in advertisements. J. Pragmat. 2005, 37, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rompay, T.J.L.; Pruyn, A.T.H. When visual product features speak the same language: Effects of shape-typeface congruence on brand perception and price expectations. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Jass, J. All Dressed Up With Something to Say: Effects of Typeface Semantic Associations on Brand Perceptions and Consumer Memory. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.R.; Bottomley, P.A. Font appropriateness and brand choice. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P.W.; Giese, J.L.; Cote, J.A. Impression Management Using Typeface Design. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.S.; Mothersbaugh, D.L. Effects of Typographic Factors in Advertising-Based Persuasion: A General Model and Initial Empirical Tests. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansard, T.C. Typographia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780511792762. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.N.; Mewhort, D.J.K. Case-sensitive letter and bigram frequency counts from large-scale English corpora. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avramides, A. Studies in the Way of Words. Philos. Books 1992, 31, 228–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Fonts and Fluency: The Effects of Typeface Familiarity, Appropriateness, and Personality on Reader Judgments. Masters’ Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. Authority; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.T. Cue Representation and Selection Effects of Arousal on Persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 1996, 22, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A.; Reese, L.; Adams, N.E. Microanalysis of action and fear arousal as a function of differential levels of perceived self-efficacy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; Volume 315, ISBN 0262130904. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, A.; Bond, S.D. Beyond beauty: Design symmetry and brand personality. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, J.M.; Dall’Olmo Riley, F.; Lomax, W. Generalizing spillover effects of goods and service brand extensions: A meta-analysis approach. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, M.; Evans, A. External Threat, Perceived Threat, and Group Identity. Soc. Sci. Q. 1985, 66, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Holbert, R.L.; Shah, D.V.; Kwak, N. Fear, Authority, and Justice: Crime-Related TV Viewing and Endorsements of Capital Punishment and Gun Ownership. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2004, 81, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.; Stenner, K. Perceived Threat and Authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 1997, 18, 741–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Kasser, T. Coherence and congruence: Two aspects of personality integration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K.L.; Nollen, S.D. Culture and Congruence: The Fit Between Management Practices and National Culture. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 753–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R.; Ashmore, R.D.; Longo, L.C. The Beauty Match-Up Hypothesis: Congruence between Types of Beauty and Product Images in Advertising. J. Advert. 1992, 21, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Mason, C. Responses to Information Incongruency in Advertising: The Role of Expectancy, Relevancy, and Humor. J. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.S.; Stammerjohan, C.A.; Coulter, R.A. Banner advertiser-web site context congruity and color effects on attention and attitudess. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.; Willer, R. The Moral Roots of Environmental Attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappin, B.M.; Capraro, V. Doing good vs. avoiding bad in prosocial choice: A refined test and extension of the morality preference hypothesis. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 79, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C.; Ariceaga, H.; Seiden, J. Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 65, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.L.; McLeod, P.; Bloomfield, R.; Allred, S. Which Moral Foundations Predict Willingness to Make Lifestyle Changes to Avert Climate Change in the USA? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capraro, V.; Rand, D.G. Do the right thing: Experimental evidence that preferences for moral behavior, rather than equity and efficiency per se, drive human prosociality. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2018, 13, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V.; Vanzo, A. Understanding Moral Preferences Using Sentiment Analysis. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, M.B.; Hepler, J.; Zimmerman, R.S.; Saul, L.; Jacobs, S.; Wilson, K.; Albarracín, D. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, L. The Extended Parallel Process Model. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V.; D’Souza, C.; Echebarria, C.; Barrutia, J.M. Nuclear power threats, public opposition and green electricity adoption: Effects of threat belief appraisal and fear arousal. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Commun. Monogr. 1994, 61, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M.W.; Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1954, 19, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kligyte, V.; Connelly, S.; Thiel, C.; Devenport, L. The Influence of Anger, Fear, and Emotion Regulation on Ethical Decision Making. Hum. Perform. 2013, 26, 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshner, G.; Bolls, P.; Wise, K. Motivated processing of fear appeal and disgust images in televised anti-tobacco ads. J. Media Psychol. 2011, 23, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.R.; Thornton, J. Fear-pattern analysis supports the fear-drive model for antispeeding road-safety TV ads. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 945–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Toffoli, R.; Zhang, Q.; Pons, F. A cross-cultural study of the persuasive effect of fear appeal messages in cigarette advertising: China and Canada. Int. J. Advert. 2001, 20, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M. Warkentin Fear Appeals and Information Security Behaviors: An Empirical Study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. Fear Won’t Do It: Promoting Positive Engagement With Climate Change Through Visual and Iconic Representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charry, K.M.; Demoulin, N.T.M. Behavioural evidence for the effectiveness of threat appeals in the promotion of healthy food to children. Int. J. Advert. 2012, 31, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurka, C.; Niederdeppe, J.; Romero-Canyas, R.; Acup, D. Pathways of Influence in Emotional Appeals: Benefits and Tradeoffs of Using Fear or Humor to Promote Climate Change-Related Intentions and Risk Perceptions. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zeev, T.; Fein, S.; Inzlicht, M. Arousal and stereotype threat. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 41, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, J.D. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation in the kitten. J. Anim. Behav. 1915, 5, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Beatty, S.E. Celebrity spokesperson and brand congruence: An assessment of recall and affect. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 21, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Only One Earth Day 200: Collapse of Global Civilization Inevitable?—Economist’s Journey to Life. Available online: http://economistjourneytolife.blogspot.com/2013/03/day-200-collapse-of-global-civilization.html (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- The 25 Most Used Typefaces in Advertising—MDirector.com. Available online: https://www.mdirector.com/en/digital-marketing/25-typefaces-advertising.html (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Capraro, V.; Rascón-Ramírez, E. Gender differences in altruism on Mechanical Turk: Expectations and actual behaviour. Econ. Lett. 2018, 170, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It Is a Match: The Impact of Congruence between Celebrity Image and Consumer Ideal Self on Endorsement Effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green Issues: Dimension of Environmental Concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, J.H. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. J. Educ. Meas. 2014, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottom, W.P. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A.; Damasio, H.; Damasio, A.R. Role of the Amygdala in Decision-Making. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 985, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A. The role of the amygdala in human fear: Automatic detection of threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolphs, R.; Gosselin, F.; Buchanan, T.W.; Tranel, D.; Schyns, P.; Damasio, A.R. A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature 2005, 433, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntoni, S.; de Langhe, B.; van Osselaer, S.M.J. Bilingualism and the Emotional Intensity of Advertising Language. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 35, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, I. Advertising as a site of language contact. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2003, 23, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauberghe, V.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W.; Dens, N. Fear, threat and efficacy in threat appeals: Message involvement as a key mediator to message acceptance. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2009, 41, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M.; Siponen, M. An Enhanced Fear Appeal Rhetorical Framework: Leveraging Threats to the Human Asset Through Sanctioning Rhetoric. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Ahn, E. The Effects of Fear Appeal: A Moderating Role of Culture and Message Type. J. Promot. Manag. 2013, 19, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Relationship | Measures | Technique | Direction | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lettering Case -> Arousal | Uppercase/lowercase—Authority/familiarity | Experiment | + | [9] |

| Familiarity—Authority | Experiment | – | [42] | |

| Authority—Arousal | Experiment | + | [9,44,45] | |

| Lettering Case -> Congruence | Appropriate typeface—Congruence | Experiment & survey | + | [34,35,36,37,38] |

| Appropriate slogan—Congruence | Experiment | + | [30] | |

| Appropriate culture—Congruence | Survey | + | [54] | |

| Arousal & Congruence -> Environmental Concern | Congruence in ad context—Ad attitude | Experiment | + | [57] |

| Congruence in ad elements—Ad effectiveness | Experiment | + | [77] | |

| Fear appeal—Environmental behavior | Experiment & interview | + | [64,74] | |

| Fear appeal—Healthy behavior | Experiment | + | [7,72,75] | |

| Threat appeal—Severity evaluation | Experiment & survey | + | [70,73,76] |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 28.023 | 2 | 14.011 | 6.228 | 0.002 |

| Within Groups | 542.166 | 241 | 2.250 | ||

| Total | 570.189 | 243 |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 33.877 | 2 | 16.938 | 9.220 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 442.745 | 241 | 1.837 | ||

| Total | 476.621 | 243 |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 23.320 | 2 | 11.660 | 4.864 | 0.008 |

| Within Groups | 577.673 | 241 | 2.397 | ||

| Total | 600.993 | 243 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Luximon, Y. Design for Sustainability: The Effect of Lettering Case on Environmental Concern from a Green Advertising Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051333

Song Y, Luximon Y. Design for Sustainability: The Effect of Lettering Case on Environmental Concern from a Green Advertising Perspective. Sustainability. 2019; 11(5):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051333

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yao, and Yan Luximon. 2019. "Design for Sustainability: The Effect of Lettering Case on Environmental Concern from a Green Advertising Perspective" Sustainability 11, no. 5: 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051333

APA StyleSong, Y., & Luximon, Y. (2019). Design for Sustainability: The Effect of Lettering Case on Environmental Concern from a Green Advertising Perspective. Sustainability, 11(5), 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051333