How Do Destinations Frame Cultural Heritage? Content Analysis of Portugal’s Municipal Websites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Culture, Heritage and Tourism: A Sustainable Synergy?

2.2. Online Communication: A Tool for Glocal Discourse

3. Materials and Method

- RQ1: What heritage assets stand out in Portugal’s municipal websites at the informative level?

- RQ2: Are there any differences between the tangible and intangible dimensions of heritage?

- RQ3: What identity frame is associated with the assets?

- RQ4: Are there any differences between the tangible and intangible dimensions in terms of their identity frames?

- RQ5: From the geographical point of view, are there any differences between regions?

- H1: There is a positive correlation between municipality population size and the amount of heritage information.

- H2: There is a positive correlation between municipal economic factors and the amount of heritage information.

- H2a: There is a positive correlation between municipal budget and the amount of heritage information.

- H2b: There is a positive correlation between municipal benefits in the field of tourism and the amount of heritage information.

- H2c: There is a positive correlation between municipal expenditure on cultural activities and the amount of heritage information.

3.1. Sample and Codebook

- Tangible cultural heritage assets—12—and their respective identity frames—12;

- Intangible cultural heritage assets—9—and their respective identity frames—9;

- Natural heritage assets—7—and their respective identity frames—7; and

- Location of heritage information on the official municipal website (0 = not located; 1 = located) or the thematic website on culture, heritage and tourism linked to the main website (0 = not located; 1 = located), which for the purposes of the sample would result in a single unit of analysis in combination with the previous variable.

- Personal and/or familial—of importance to the individual and/or the members of a family.

- Local—of importance to people of one village or local community.

- Regional—of importance to people of more than one village or local community group.

- Provincial—of importance to people extending beyond one city or town.

- National—of importance to people of more than one province.

- International—of importance to people of more than one nation [67] (p. 183).

- Official classification of assets: world heritage site, national historic site, national monument, monument of public interest, monument of municipal interest, etc.

- Nomenclature of assets. Examples are the conservation of unique heritage sites: ‘Southwest writing’, whose framing is regional; and the ‘National fair of green wine, gastronomy and crafts’ of Castelo de Paiva, the framing of which is national.

- Identification of keywords in the content of the information. For instance, the ‘Cod Festival’ of Ílhavo, where ‘local history and traditions are aligned’, the framing of which is local; and Ponte de Lima, ‘Portugal’s oldest village’, the framing of which is national.

3.2. Coding, Reliability and Created Indexes

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

- If what interests the tourist now is more than experiencing one aspect of a culture—nature, monuments, gastronomy, etc.—experiencing a culture as a whole, its identity, its way of life, then all cultures end up having the same opportunities to attract visitors, and not only those that have sea, or monuments, or festivals, etc.

- As a result of globalization, cultures become hybrid and even homogeneous. What is increasingly valued by potential visitors is the difference, uniqueness and authenticity of each culture—as we also see in the growing demand for the distant, the exotic and the archaic. Each culture must therefore strive to maintain this difference, without yielding to the temptation to become increasingly ‘touristy’ in the worst sense of the term.

- The Information and Communication Technologies—in our case, websites—that characterize today’s digital society, accessible to everyone, more or less easy to use and of global and instant reach [80], allow each culture and community to ensure its public visibility. These technologies should be used in a persuasive way to attract visitors, but they also must represent locals.

- The success of a destination or a culture can lead to the attraction of a mass of visitors such that, in a short time, these visitors become invasive, endangering the traditions and ways of life of the community—as is currently happening in cities like Lisbon or Porto. The question that arises in this case is the sustainability of tourism: how to promote a destination without the risk of contributing to its destruction or degradation?

- As ‘the different’ is being incorporated into global tourist flows, it may tend to cancel out genuine difference, increasingly becoming culture created for the tourist.

- The public visibility of a community or a culture progressively depends on the information and messages of its own visitors, and less favorable opinions can become a serious risk to the tourist destination.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Heritage Elements (Dichotomous Nominal Variables) | αk | Frames (Ordinal Variables) | αk |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Religious buildings | 0.89 | 2. Religious buildings frame | 0.89 |

| 3. Museums and culture houses | 0.64 | 4. Museums and culture houses frame | 0.67 |

| 5. Civil and military buildings | 0.75 | 6. Civil and military buildings frame | 0.66 |

| 7. Libraries and archives | 0.80 | 8. Libraries and archives frame | 0.48 |

| 9. Archaeological remains | 0.88 | 10. Archaeological remains frame | 0.80 |

| 11. Statues and sculptures | 0.84 | 12. Statues and sculptures frame | 0.83 |

| 13. Parks and gardens | 0.71 | 14. Parks and gardens frame | 0.74 |

| 15. Theatres and amphitheatres | 0.63 | 16. Theatres and amphitheatres frame | 0.58 |

| 17. Urban complexes | 0.81 | 18. Urban complexes frame | 0.75 |

| 19. Squares and markets | 0.73 | 20. Squares and markets frame | 0.74 |

| 21. Bullrings | 0.66 | 22. Bullrings frame | 0.68 |

| 23. Cathedrals and basilicas | 1 | 24. Cathedrals and basilicas frame | 1 |

| 25. Gastronomy | 0.80 | 26. Gastronomy frame | 0.54 |

| 27. Religious events | 0.73 | 28. Religious events frame | 0.68 |

| 29. Festive events | 0.78 | 30. Festive events frame | 0.66 |

| 31. Traditional crafts | 0.89 | 32. Traditional crafts frame | 0.90 |

| 33. Performing arts | 0.54 | 34. Performing arts frame | 0.47 |

| 35. Important public figures | 0.65 | 36. Important public figures frame | 0.57 |

| 37. Oral traditions | 0.80 | 38. Oral traditions frame | 0.83 |

| 39. Popular customs | 0.79 | 40. Popular customs frame | 0.78 |

| 41. Bullfighting | 0.84 | 42. Bullfighting frame | 0.82 |

| 43. Rivers & fluvial environments | 0.68 | 44. Rivers & fluvial environments frame | 0.60 |

| 45. Landscapes and roads | 0.66 | 46. Landscapes and roads frame | 0.54 |

| 47. Flora and fauna | 0.72 | 48. Flora and fauna frame | 0.68 |

| 49. Mountains | 0.63 | 50. Mountains frame | 0.61 |

| 51. Nature reserves | 0.83 | 52. Nature reserves frame | 0.85 |

| 53. Coastal formations | 1 | 54. Coastal formations frame | 1 |

| 55. Caverns | 1 | 56. Caverns frame | 1 |

| Location of Heritage Information (dichotomous nominal variables) | |||

| 57. Institutional website | 1 | 58. Thematic website | 0.65 |

Appendix B

| Index | Variables | M | SD | αc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Heritage Information Index (CHI2) | 1. Religious buildings | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.60 |

| 2. Museums and culture houses | ||||

| 3. Civil and military buildings | ||||

| 4. Libraries and archives | ||||

| 5. Archaeological remains | ||||

| 6. Statues and sculptures | ||||

| 7. Parks and gardens | ||||

| 8. Theatres and amphitheatres | ||||

| 9. Urban complexes | ||||

| 10. Squares and markets | ||||

| 11. Bullrings | ||||

| 12. Cathedrals and basilicas | ||||

| 13. Gastronomy | ||||

| 14. Religious events | ||||

| 15. Festive events | ||||

| 16. Traditional crafts | ||||

| 17. Performing arts | ||||

| 18. Important public figures | ||||

| 19. Oral traditions | ||||

| 20. Popular customs | ||||

| 21. Bullfighting | ||||

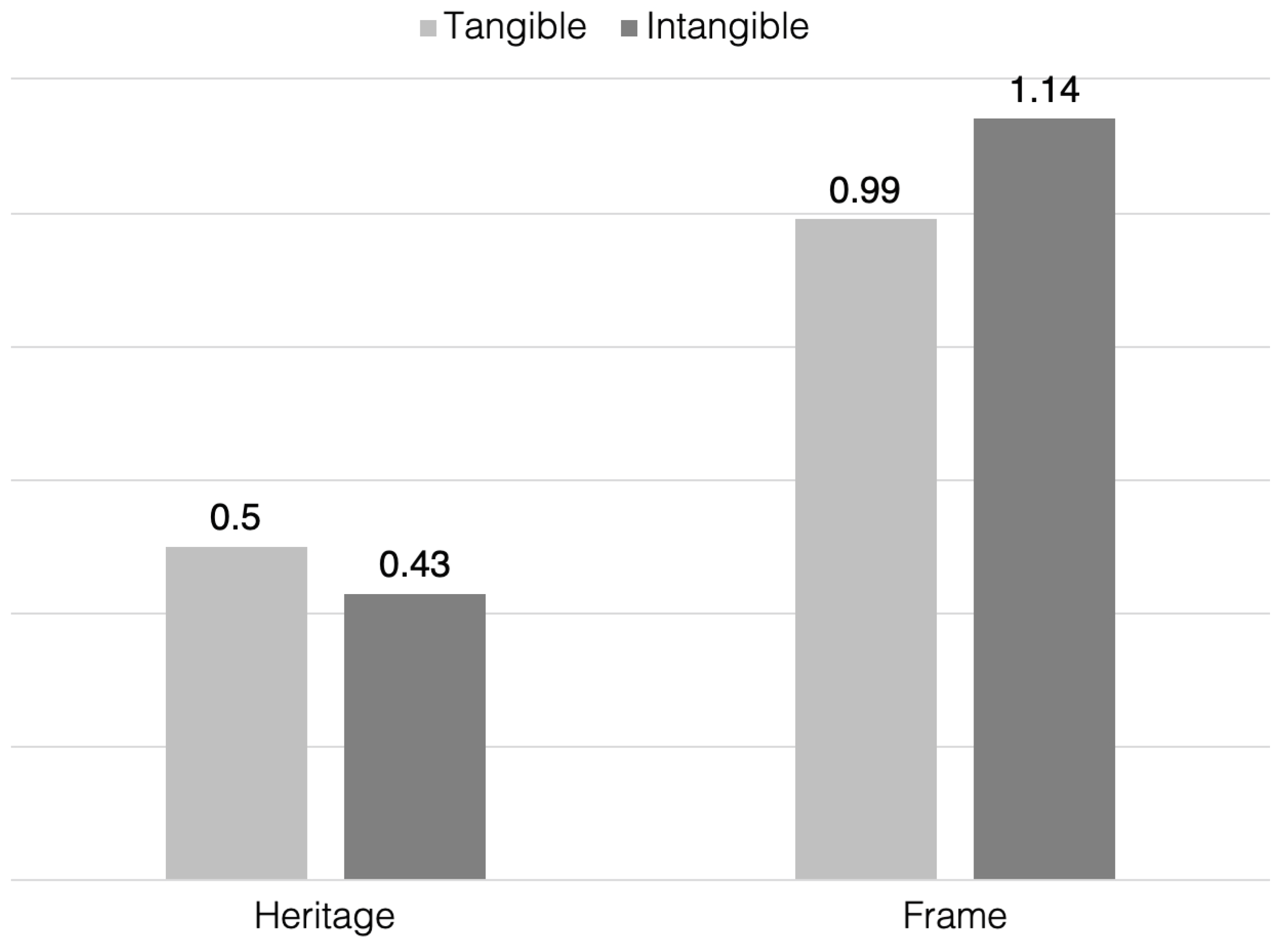

| Tangible Cultural Heritage Information Index (TCHI2) | 1. Religious buildings | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.55 |

| 2. Museums and culture houses | ||||

| 3. Civil and military buildings | ||||

| 4. Libraries and archives | ||||

| 5. Archaeological remains | ||||

| 6. Statues and sculptures | ||||

| 7. Parks and gardens | ||||

| 8. Theatres and amphitheatres | ||||

| 9. Urban complexes | ||||

| 10. Squares and markets | ||||

| 11. Bullrings | ||||

| 12. Cathedrals and basilicas | ||||

| Intangible Cultural Heritage Information Index (ICHI2) | 1. Gastronomy | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.52 |

| 2. Religious events | ||||

| 3. Festive events | ||||

| 4. Traditional crafts | ||||

| 5. Performing arts | ||||

| 6. Important public figures | ||||

| 7. Oral traditions | ||||

| 8. Popular customs | ||||

| 9. Bullfighting | ||||

| Cultural Heritage Frame Index (CHFI) | 1. Religious buildings frame | 1.02 | 0.59 | 0.95 |

| 2. Museums and culture houses frame | ||||

| 3. Civil and military buildings frame | ||||

| 4. Libraries and archives frame | ||||

| 5. Archaeological remains frame | ||||

| 6. Statues and sculptures frame | ||||

| 7. Parks and gardens frame | ||||

| 8. Theatres and amphitheatres frame | ||||

| 9. Urban complexes frame | ||||

| 10. Squares and markets frame | ||||

| 11. Bullrings frame | ||||

| 12. Cathedrals and basilicas frame | ||||

| 13. Gastronomy frame | ||||

| 14. Religious events frame | ||||

| 15. Performing arts frame | ||||

| Tangible Cultural Heritage Frame Index (TCHFI) | 1. Religious buildings frame | 0.99 | 0.70 | 0.96 |

| 2. Museums and culture houses frame | ||||

| 3. Civil and military buildings frame | ||||

| 4. Libraries and archives frame | ||||

| 5. Archaeological remains frame | ||||

| 6. Statues and sculptures frame | ||||

| 7. Parks and gardens frame | ||||

| 8. Theatres and amphitheatres frame | ||||

| 9. Urban complexes frame | ||||

| 10. Squares and markets frame | ||||

| 11. Bullrings frame | ||||

| Intangible Cultural Heritage Frame Index (ICHFI) | 1. Gastronomy frame | 1.14 | 0.86 | 0.58 |

| 2. Religious events frame | ||||

| 3. Festive events frame | ||||

| 4. Traditional crafts frame | ||||

| 5. Performing arts frame | ||||

| 6. Important public figures frame | ||||

| 7. Oral traditions frame | ||||

| 8. Popular customs frame | ||||

| M (αc) = 0.70 | ||||

References

- Standing, C.; Tang-Taye, J.P.; Boyer, M. The Impact of the Internet in Travel and Tourism: A Research Review 2001–2010. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.; Stark, J.F.; Cooke, P. Experiencing the Digital World: The Cultural Value of Digital Engagement with Heritage. Herit. Soc. 2016, 9, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidhardt, J.; Werthner, H. IT and tourism: Still a hot topic, but do not forget IT. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Zhan, F. Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatanti, M.N.; Suyadnya, I.W. Beyond User Gaze: How Instagram Creates Tourism Destination Brand? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Gibson, L.K. Digitisation, digital interaction and social media: Embedded barriers to democratic heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, L.M.; Motamed, B.; Ghadirinia, M. Investigating heritage sites through the lens of social media. J. Archit. Urban. 2018, 42, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Liang, C.; Gu, D. Heritage Image and Attitudes toward a Heritage Site: Do They Really Mediate the Relationship between User-Generated Content and Travel Intentions toward a Heritage Site? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieder, T.K.; Adukaite, A.; Cantoni, L. Mobile Apps Devoted to UNESCO World Heritage Sites: A Map. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014; Xiang, Z., Tussyadiah, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Ghali, K.; Cherrett, T.; Speed, C.; Davies, N.; Norgate, S. Tourism and the smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. Prediction, explanation and big(ger) data: A middle way to measuring and modelling the perceived success of a volunteer tourism sustainability campaign based on ‘nudging’. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Tourism on the Verge. Analytics in Smart Tourism Design. Concepts and Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.I.; Tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. User experience model for augmented reality applications in urban heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, R.; Khoo-Lattimore, C. New realities: A systematic literature review on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Tian, F.; Buhalis, B.; Weber, J.; Zhang, H. Tourists as Mobile Gamers: Gamification for Tourism Marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1124–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Abrantes, J.L.; Kastenholz, E. Innovation, tourism and social networks. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2014, 21–22, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, D.M.; Costa, C. Turismo: Tendências de evolução. PRACS Revista Eletrônica de Humanidades do Curso de Ciências Sociais da UNIFAP 2017, 10, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholitabar, S.; Alipour, H.; Costa, C. An Empirical Investigation of Architectural Heritage Management Implications for Tourism: The Case of Portugal. Sustainability 2018, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, P.M.C.; Alén-González, E.; Liberato, D.F.V.A. Digital Technology in a Smart Tourist Destination: The Case of Porto. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 25, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet World Stats. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- Banco de Portugal. Available online: https://www.bportugal.pt (accessed on 7 January 2019).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2016. Highlights; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.A.; Gretzel, U. Success factors for destination marketing web sites: A qualitative meta-analysis. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanitzsch, T. Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory. Commun. Theory 2007, 17, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations. Software of the Mind. Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Human Groups and Social Categories; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C.; Oakes, P.J.; Haslam, S.A.; McGarty, C. Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Globalisation and identity. A comparative perspective. Transfer. J. Contemp. Cult. 2006, 1, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. Natural and Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2005, 11, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, R.; Snyder, M. The role of heritage conservation districts in achieving community economic development goals. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehl, P.F.; Prescott, C. The Future of Heritage in a Globalized World. In Heritage in the Context of Globalization. Europe and the Americas; Biehl, P.F., Prescott, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, F.G.; Giusti, J.D. Cultural heritage, tourism and regional competitiveness: The Motor Valley cluster. Cityculture Soc. 2012, 3, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, C.; Valle, E. Tourist Intensity in the World, 1995–2015: Two Measurement Proposals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Pride, R. Destination Brands: Managing Place Reputation, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). The Impact of Culture on Tourism; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Galí-Espelt, N. Identifying cultural tourism: A theoretical methodological proposal. J. Herit. Tour. 2012, 7, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Principales tendencias en el turismo contemporáneo. Política Soc. 2005, 42, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.C.; Milne, S.; Fallon, D.; Pohlmann, C. Urban Heritage Tourism. The Global-Local Nexus. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, N.; Dredge, D. Local tourism governance: A comparison of three network approaches. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. On Glocalization: Or Globalization for some, Localization for some Others. Thesis Elev. 1998, 54, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G. Globalization: A Basic Text; Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity. In Global Modernities; Featherstone, M., Lash, S., Robertson, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1995; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D.C. Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1225–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L. The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, R.W.; Kaplan-Weinger, J. Official Tourism Websites: A Discourse Analysis Perspective; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M.; Matthes, J.; Pellicano, L. Nature, Sources, and Effects of News Framing. In The Handbook of Journalism Studies; Wahl-Jorgensen, K., Hanitzsch, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.; Gretzel, U. Designing persuasive destination websites: A mental imagery processing perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, P.; Li, L.H. Global and local interactions in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B. Tourism and Glocalization. ‘Local’ Tour Guiding. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kautsky, R.; Widholm, A. Online Methodology: Analysing News Flows of Online Journalism. Westminst. Pap. Commun. Cult. 2008, 5, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S.J. The microscope and the moving target: The Challenge of applying content analysis to the World Wide Web. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2000, 77, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjøvaag, H.; Stavelin, E. Web media and the quantitative content analysis: Methodological challenges in measuring online news content. Converg. Int. J. Res. Into New Media Technol. 2012, 18, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weare, C.; Lin, W.Y. Content analysis of the World Wide Web. Opportunities and challenges. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2000, 18, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Igartua, J.J. La difusión del Patrimonio a través de Internet. El caso de Castilla y León. Cuadernos de Turismo 2012, 30, 191–217. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Igartua, J.J.; Rodríguez-de-Dios, I. Identity-related implications of the dissemination of cultural heritage through the Internet: A study based on Framing Theory. Commun. Soc. 2018, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Serra, P.; Mangana, R. Local development and tourism. The socio-economic impact of digital communication in Portugal. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2017, 72, 1515–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffe, D.; Lacy, S.; Fico, F. Analyzing Media Messages. Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Feeney, M.K. Determinants of Information and Communication Technology Adoption in Municipalities. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2016, 46, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.W.; Bramley, R. Defining Heritage Values and Significance for Improved Resource Management: An application to Australian tourism. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydland, L.; Grahn, W. Identifying heritage values in local communities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M. Charting the liquidity of online news: Moving towards a method for content analysis of online news. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2012, 74, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Krippendorff, K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun. Methods Meas. 2007, 1, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Statistical Methods for Communication Science; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.; Smith, M. Politics, power and play: The shifting contexts of cultural tourism. In Cultural Tourism in a Changing World: Politics, Participation and (re) Presentation; Smith, M., Robinson, M., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2006; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, N.B. The glocalisation of heritage through tourism. Balancing standardisation and differentiation. In Heritage and Globalization; Labadi, S., Long, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 130–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Bussiness a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Serra, P. (Eds.) Cultura, Património e Turismo na Sociedade Digital: Uma perspetiva ibírica; Editora LabCom.IFP: Covilhã, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Marques, L. Creating Synergies between Cultural Policy and Tourism for Permanent and Temporary Citizens; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Framing theory: Towards a critical imagination in heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Law, R.; Wei, J. Knowledge mapping in travel website studies: A scientometric review. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heritage Assets | Framing | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Frame | Local | Regional | National | Global | ||

| Tangible Cultural Heritage | ||||||

| • Religious buildings | 38.3 | 19.5 | 5.2 | 21.1 | 3.2 | 87.3 |

| • Museums and culture houses | 33.1 | 27.3 | 12.3 | 9.7 | 3.9 | 86.3 |

| • Civil and military buildings | 35.7 | 17.5 | 5.2 | 23.4 | 3.6 | 85.4 |

| • Libraries and archives | 30.2 | 38.3 | 0.6 | 11.4 | 0.6 | 81.1 |

| • Archaeological remains | 26.6 | 8.4 | 4.5 | 10.1 | 3.6 | 53.2 |

| • Statues and sculptures | 29.5 | 11.4 | 1.6 | 6.5 | 1 | 50 |

| • Parks and gardens | 35.1 | 6.5 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 44.5 |

| • Theatres and amphitheatres | 24.4 | 11.7 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 41.6 |

| • Urban complexes | 15.3 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 2.9 | 32.1 |

| • Squares and markets | 19.2 | 2.3 | - | 1 | - | 22.5 |

| • Bullrings | 2.9 | 1.6 | - | 1 | - | 5.5 |

| • Cathedrals and basilicas | 1.3 | 0.3 | - | 3.2 | 0.6 | 5.4 |

| Intangible Cultural Heritage | ||||||

| • Gastronomy | 22.7 | 24.4 | 31.5 | 8.4 | 4.5 | 91.5 |

| • Religious events | 49.7 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 7.8 | 66.9 |

| • Festive events | 47.4 | 11 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 66.1 |

| • Traditional crafts | 26 | 20.1 | 6.2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 58.1 |

| • Performing arts | 14 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 9.4 | 37.7 |

| • Important public figures | 5.8 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 12.3 | 2.9 | 24.2 |

| • Oral traditions | 5.8 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 19.8 |

| • Popular customs | 5.2 | 8.4 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 17.1 |

| • Bullfighting | 2.9 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 7.1 |

| Natural Heritage | ||||||

| • Rivers and fluvial environments | 35.1 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 6.5 | 56.5 |

| • Landscapes and roads | 30.5 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 44.7 |

| • Mountains | 26 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 38 |

| • Flora and fauna | 16.2 | 6.8 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 34.7 |

| • Nature reserves | 6.8 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 11.7 | 4.9 | 27.6 |

| • Coastal formations | 13.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 22.3 |

| • Caverns | 4.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 7.3 |

| Variables (Hypotheses) | Sources | CHI2 | CHFI | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of residents (H1) | http://www.ine.pt/ | 0.13 * | 0.19 ** | 306 |

| Budget (H2a) | http://www.portalautarquico.pt/ | 0.28 *** | 0.37 *** | 306 |

| Benefits derived from tourism (H2b) | http://www.pordata.pt/ | 0.13 + | 0.14 + | 167 |

| Expenditure on cultural activities (H2c) | http://www.ine.pt/ | 0.18 ** | 0.24 *** | 306 |

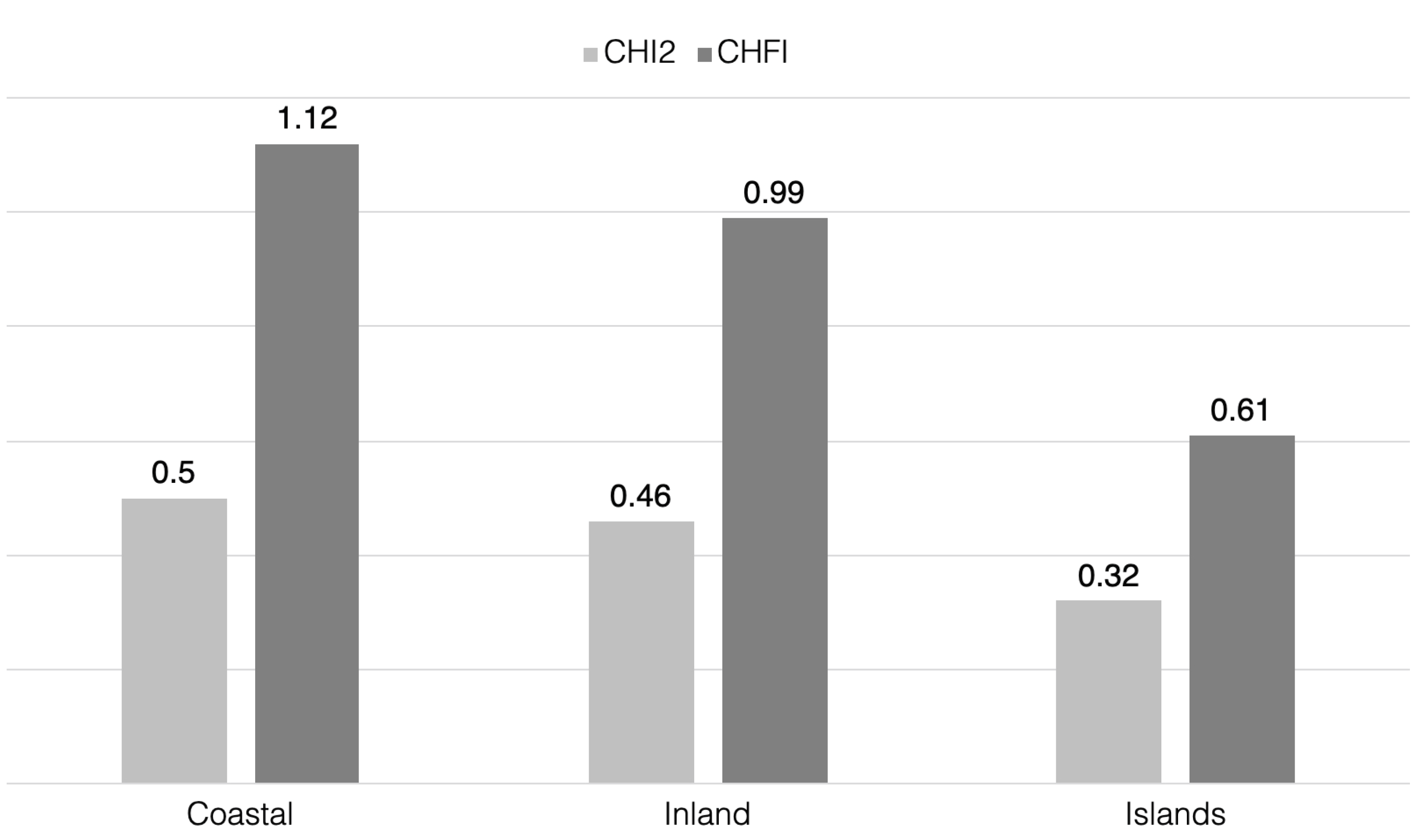

| NUTS II Region | M CHI2 | SD | M CHFI | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 0.50 | 0.12 | 1.14b | 0.63 | 86 |

| Centre | 0.46 | 0.12 | 1.08 | 0.52 | 100 |

| Alentejo | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 58 |

| Metropolitan Area of Lisbon | 0.51a | 0.14 | 1.06 | 0.61 | 18 |

| Algarve | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 16 |

| Autonomous Region of Azores | 0.31a | 0.12 | 0.46b | 0.46 | 19 |

| Autonomous Region of Madeira | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 11 |

| Total | 0.47 | 0.14 | 1.02 | 0.59 | 308 |

| Thematic Website | Total % | Institutional Website | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, the Information Is Located Here | No, the Information Is not Located Here | ||

| Yes, the information is located here | 25.6 | 25.2– | 100+ |

| No, the information is not located here | 74.4 | 74.8+ | 0– |

| N | 308 | 306 | 2 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Serra, P. How Do Destinations Frame Cultural Heritage? Content Analysis of Portugal’s Municipal Websites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040947

Piñeiro-Naval V, Serra P. How Do Destinations Frame Cultural Heritage? Content Analysis of Portugal’s Municipal Websites. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040947

Chicago/Turabian StylePiñeiro-Naval, Valeriano, and Paulo Serra. 2019. "How Do Destinations Frame Cultural Heritage? Content Analysis of Portugal’s Municipal Websites" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040947

APA StylePiñeiro-Naval, V., & Serra, P. (2019). How Do Destinations Frame Cultural Heritage? Content Analysis of Portugal’s Municipal Websites. Sustainability, 11(4), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040947