Abstract

This study considers two types of consumers: those without preference difference, and those that prefer organic agricultural products. It constructs two two-stage hoteling behavior-based pricing models and solves for the optimal loyalty price and poaching price of the two types of enterprises. It analyzes the influence of subsidies on the pricing of the two types of products and corporate profits. The study also undertakes numerical simulation for further analysis, finding that green subsidies are negatively correlated with the loyalty price and poaching price of organic agricultural products, but that they will not affect the difference between the two types of prices. When the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, the size of green subsidy affects the relationship between the prices of the two types of products. However, when organic agricultural products do not dominate the initial market, green subsidies do not affect the size of the relationship between the two prices of the two types of products. When the initial market position of organic agricultural products is different, the types of competing customers are different between the two types of enterprises, and the intensity of competition will increase with the increase of subsidies. Green subsidies increase the profits of organic agricultural enterprises and reduce the profits of conventional agricultural enterprises.

1. Introduction

To promote sustainable agricultural development, organic agricultural products are encouraged to limit the use of artificial fertilizers and pesticides in the production process. As early as 1985, for the healthy and orderly development of agriculture, the United States and Europe implemented projects related to green environmental subsidies in agriculture [1], and formulated “environmental quality incentive plans” and other subsidies for agricultural production. In 2016, China passed a reform plan to establish a green ecology-oriented agricultural subsidy system, stating that it is necessary to steer agricultural development towards organic agriculture through subsidies. The types of green agriculture subsidies are various [2,3], e.g., ad valorem, specific, decoupled payments, etc., and the most widely used is the fund subsidy. Green agricultural subsidies can reduce the production costs of organic agricultural products, thus enhancing their competitiveness with conventional agricultural products in the market, and promoting the healthy development of organic agriculture.

Organic agricultural products have the characteristics of high quality and nutrition, in addition to being environmentally friendly, so their selling price is higher than that of conventional agricultural products. As income rises in developing countries such as China, more consumers are trying to buy organic products to improve their quality of life. In recent years, the market share of organic agricultural products in China has grown rapidly. According to the China green consumer report 2016 by Ali Research, the number of green consumers on the Alibaba platform increased fourfold from 2011 to 2015; some were consumers of organic products. When organic and conventional products are sold competitively in the market, especially online, more and more enterprises adopt behavior-based pricing strategies for new and existing customers. For example, on the Tmall mall in October 2018, an enterprise sold an infant milk powder (6–12 months old), Abbott Eleva pure (conventional product), to loyal customers at 30.33 CNY/100 g (loyalty price), and to new customers at 17.5 CNY/100 g (poaching price); Mead Johnson pure (green product) was sold to loyal customers at 46.67 CNY/100 g (loyalty price) and to new customers at 39 CNY/100 g (poaching price). At Sam’s in January 2019, for its own-brand northeast grain fragrant rice (conventional product), the price for loyal customers was 6.98 CNY/kg, and the price for new customers was about 6.28 CNY/kg (the reduced price after using the new coupons); the yudaofu-branded ecological rice (organic product) on sale was priced at 10.9 CNY/kg for loyal customers and 9.81 CNY/kg for new customers (after the coupon is used). Behavior-based pricing is focused on assuming that loyal customers will not easily change with respect to their spending habits, while offering a differential price to attract new customers, so as to realize the maximization of corporate profits.

Recent studies have shown that the quality of organic agricultural products is not different from that of conventional agricultural products and will not have different effects on human health [4,5]. Therefore, some consumers have no preference difference between organic agricultural products and conventional products. Therefore, when considering two types of consumers with different preferences for organic agricultural products in the market, this study takes into account the pricing decisions of enterprises producing organic agricultural products with green agricultural subsidies, and those producing conventional agricultural products. We will analyze the impact of green agricultural subsidies on the pricing and profits of both organic agricultural product enterprises and conventional agricultural product enterprises, to provide a decision-making reference for pricing in agricultural product enterprises, and further improve the green agricultural subsidies policy.

2. Literature Review

With the rapid development of information technology, enterprises can now track and store information about the purchase history of individual customers, such as location, preference, and so on, through information tracking tools. Acquiring such information makes it feasible for enterprises to set behavior-based pricing [6]; enterprises divide consumers into “loyal customers” and “poaching customers” [7]. For “loyal customers” and “poaching customers”, the enterprise will implement different degrees of premium or discount as per their historical purchase information [8,9]. There are many factors that affect the pricing of enterprise behavior. For example, Ki-Eun (2014) [10] analyzes the impact of switching costs on price, profit and consumers. Esteves and Reggiani (2014) [11] analyzes the impact of demand elasticity on behavior-based price discrimination’s profit, consumer, and welfare effects. Colombo (2018) [12] develops a discriminatory pricing model based on behavior and customer characteristics, believing that consumers are heterogeneous in taste and price sensitivity, and the influence of price discrimination depends on the type and level of heterogeneity of consumers.

Various factors can affect consumer preference for organic agricultural products. Such factors as price [13,14,15], consumers’ environmental awareness [16,17,18], social and moral values [19], subjective norms [20,21], perceived behavioral control [20,22] and consumers’ trust in organic food [14,23] are considered to be important factors leading to consumers’ preference for organic products. Although organic products represent higher quality and better nutrition [24] compared to conventional products, products labeled “organic” are more likely to result in purchase intention [16,25]. On the other hand, some studies [26,27] show that organic food and conventional food are roughly similar in nutritional quality, and the actual pollution levels of these two kinds of food is generally lower than the acceptable limit [28]. Therefore, there is a group of consumers who prefers to buy organic agricultural products and a group of consumers who have no preference for organic agricultural products. The types of consumers will also directly affect the pricing of enterprises through the impact of product demand, thus affecting the profits of enterprises.

Capital subsidy has a significant impact on enterprise decision-making. Subsidies will directly affect companies’ pricing. Mu et al. [29] studied dynamic pricing of perishable assets under subsidy; a dynamic subsidy strategy was proposed for the government to uphold the principle of fairness. Government subsidies have an impact on the dual-channel recycling pricing of waste electrical and electronic products [30,31]. In addition, Chen et al. [32] analyzed the influence of consumers’ preference and government subsidies on the optimal decision-making, sales volume and profit of manufacturers, retailers and third parties. Shu et al. [33] discussed the influence of changes in government subsidy on decisions in the biological agricultural products supply chain, and performed a comparative analysis of two different subsidy models. All the above studies analyzed the impact of different subsidy methods and strategies on the price and profit of enterprises from the perspective of the supply chain, but did not analyze the impact of subsidies on behavior-based pricing.

In conclusion, the type of consumer affects purchasing preference, and thus affects the demand for organic agricultural products. In addition, green subsidies directly affect the cost of producing organic products. Previous studies have not considered the impact of the two factors on the behavior-based pricing of organic agricultural products. Based on the hoteling model, this paper discusses the behavioral pricing and decision-making of organic agricultural enterprises and conventional agricultural enterprises considering different consumer types under green agricultural subsidies, and analyzes the impact of subsidies on the pricing and profit of the two types of agricultural behavior-based pricing enterprises. Our analysis proceeds as follows. Section 3 sets up the pricing model, whereby enterprises can price discriminate between loyal buyers and consumers who purchase a viral brand, and examine the scope of green subsidy units. Section 4 analyzes the impact of green subsidies on enterprise pricing. Section 5 discusses the influence of green subsidies on corporate profits. Section 6 sums up the main idea and concludes.

3. The Model

3.1. Hypothesis of the Research Object

At present, most supermarkets have special organic produce counters to distinguish them from conventional produce. Based on the hoteling model, we suppose that there are only two firms, labeled G and L, who produce organic agricultural products and conventional agricultural products, respectively. Firm G is on the left side of the unit interval, and only produces organic agricultural products. Since the production and processing requirements of organic agricultural products are significantly higher than those of conventional agricultural products, we assume a certain marginal cost C (C > 0). To encourage and support the production of organic products, the state usually gives corresponding subsidies S (0 < S < C) to green agricultural enterprises. Firm L is on the right side of this interval, and only produces conventional agricultural products. Its marginal cost of production is 0. This study assumes that there are only two types of consumers in the market: no preference; and organic preference. No preference consumers think that conventional agricultural products are as healthy and safe as organic agricultural products, while organic preference consumers think that organic agricultural products are better than conventional agricultural products in health, taste, and quality.

This study rules out the possibility that a consumer may have purchased both organic and conventional agricultural products at each stage, and assumes that each consumer buys one unit of consumption from only one of the firms. Furthermore, consumers are uniformly distributed on the unit interval. Each consumer x, x ∈ [0, 1], is endowed with a history of purchase. There are two periods, t = 0 and t = 1. Our analysis starts in period t = 1, in which sales data from t = 0 are considered as recorded history. In period t = 0, firms that produce organic and conventional agricultural products engage in price competition. Purchase histories are public information. Let the function h(x): [0, 1] → {G, L} describe the purchase history of each consumer; thus, h(x) = G implies that the consumer indexed by x has purchased organic agricultural products in period t = 0. Similarly, h(x) = L denotes a consumer who purchased conventional agricultural products in period t = 0. In period t = 1, consumers seek diversification of purchase. Consumers who originally purchased conventional agricultural products may continue to purchase them, or may buy organic agricultural products for reasons of environmental protection, diversification, or novelty. Consumers who used to buy organic agricultural products will also have two choices: remain loyal to organic agricultural products or try conventional agricultural products. Research by Nandi et al. [32] shows that even deeply loyal organic consumers switch between organic products and conventional products. With perfect information about the purchase history of consumers, each firm can engage in behavior-based price discrimination. In this section, we analyze pricing decisions in the period t = 1. The relevant parameters are set as follows:

Γ: Proportion of no preference consumers in the total number of consumers

v: Additional effects perceived by consumption of organic agricultural products

C: Marginal cost of organic agricultural products

S: Government subsidies for organic agricultural products

pG: Loyalty price of firm G; the price firm G sets for consumers who have already purchased G (organic agricultural products) before

qG: Poaching price of firm G; the price firm G sets for those consumers who earlier purchased L (conventional agricultural products)

pL: Loyalty price of firm L; the price firm L sets for consumers who have already purchased L (conventional agricultural products) before

qL: Poaching price of firm L; the price firm L sets for consumers who earlier purchased G (organic agricultural products)

and γ + θ = 1, 0 < S < C < v < 1.

3.2. The Two-Stage Oligopoly Model

Based on the above hypothesis and referring to relevant literature such as Gehrig [9], the utility of non-preferred consumers with a ratio of γ indexed by xγ, and with a purchase history of brand h(x) ∈ G, L, is defined by

The parameter U measures the consumer’s basic satisfaction, while τ ≥ 0 is the “transportation cost” parameter. A low value of τ indicates intense brand competition, whereas a high value of τ indicates the significant market power of brand producing firms.

Since we assume only two types of consumers, 1 − γ represents the proportion of consumers who prefer organic agricultural products. Let 1 − γ = θ. The utility of organic preference consumers with a ratio of θ, indexed by xθ with a purchase history of brand h(x) ∈ G, L, is defined by

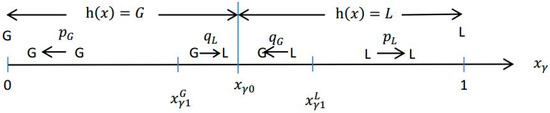

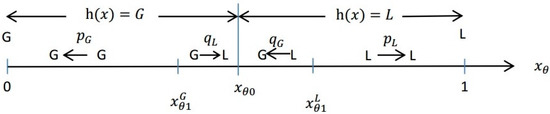

Consumers who bought organic agricultural products G in period t = 0 may buy conventional agricultural product L in period t = 1 due to various factors such as price. Let be given. Consumers indexed by continue to buy product G at period t = 1 and enjoy loyalty prices. Consumers indexed by , who have purchased product G before, switch to product L in period t = 1. They are denoted by , which is implicitly determined from , as shown in Figure 1. is analogously determined from . Similarly, by using as the demarcation points, we can distinguish the loyalty price and the poaching price of organic preference consumers in t = 1 period, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Consumption distribution of non-preferred consumers .

Figure 2.

Consumption distribution of organic preference consumers .

Substituting Equations (1), (2), (3), and (4) into equations (5) and (6), and solving the Nash equilibrium, it is clear that the Nash equilibrium price now is

Let

For profit:

The profit difference between Firm G and Firm L in the second stage is

3.3. Scope of Unit Green Subsidies

When subsidies are too small, green agricultural producers may withdraw from the market due to high costs and lack of competitiveness. Conversely, when subsidies are too high, conventional agricultural producers will withdraw from the market due to lack of competitiveness. Therefore, as this study focuses on the price competition between two types of products, we make the following assumptions for the scope of unit green subsidy S:

- When , ;

- When , ;

- When , .

Since the product prices are necessarily greater than or equal to the cost of producing the product, it satisfies:

Considering the purchasing situation of consumers in period t = 0, and that x0 represents the inherited market of organic agricultural products, .

According to formula (14)–(17), a value range of x0 can be obtained as follows:

then,

Therefore, when , that is, when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is inferior, green subsidies given by the government must be changed within the scope of [] to ensure that the two types of agricultural product enterprises do not lose money.

When , that is, when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is in a state of fierce competition, green subsidies given by the government must be changed within the scope of [] to ensure that the two types of agricultural product enterprises do not lose money.

When , that is, when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, green subsidies given by the government must be changed within the scope of [] to ensure that the two types of agricultural product enterprises do not lose money.

4. Impact of Green Subsidies on Enterprise Pricing

Proposition 1.

Regardless of the value of X0, S is linearly and negatively correlated with the pricing of organic agricultural products, with a coefficient of −2/3.

According to the different scopes of inherited market X0 of organic agricultural products, the range of green subsidies will also change accordingly. However, in any case, when green subsidies increase, pG, qG, pL, qL decrease, and the decrease of pG and qG is more significant than that of pL and qL. Therefore, under the Nash equilibrium condition, the pricing strategies of enterprises producing two types of agricultural products in the period t = 1 are typically linearly negatively correlated with the subsidies received by organic agricultural product manufacturers, and the increased subsidies have a more significant negative impact on the loyalty price and poaching price pricing of organic agricultural product enterprises. This is because subsidies will directly affect the pricing of organic agricultural products and indirectly affect the pricing of conventional agricultural products.

Therefore, when government subsidies for organic agricultural products increase, the pricing strategy of enterprises producing organic agricultural products is to reduce the overall pricing level (including loyalty price and poaching price), to take a higher market share. Companies that produce conventional agricultural products will also choose to lower the overall price level. Because at this time, if the enterprises producing conventional agricultural products do not lower their prices, their relative competitiveness will be insignificant or even disappear, confronted by consumers who pursue high quality and low price. However, the range of price reduction of such enterprises is relatively small.

Corollary 1.

No matter how S changes, it will not affect the price difference between the loyalty price of organic agricultural products and the poaching price.

, . Therefore, green subsidies will not affect the difference between the loyalty prices and poaching prices of enterprises manufacturing either organic or conventional agricultural products. As with the increase in green subsidies, the loyalty price of organic agricultural products will decrease by the same amount as the poaching price; therefore, the subsidy will not affect the price difference. Similarly, the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products will decrease by the same amount as the poaching price when the subsidy increases, and this change in subsidy will not affect the price difference.

Proposition 2.

When the inherited market of organic agricultural products is inferior (),, green subsidies will not affect the size of the relationship between the prices of two types of enterprises.

When , from , , then , , and there is no intersection between and . If , then . Set , If point S1 exists, it must satisfy the constraint condition in 3.3: , then . We know from , now τ has to satisfy both and . Therefore, the point S1 does not exist, that is, when , there is no intersection between and . As the price of the organic agricultural products is higher than that of average agricultural products, accordingly, .

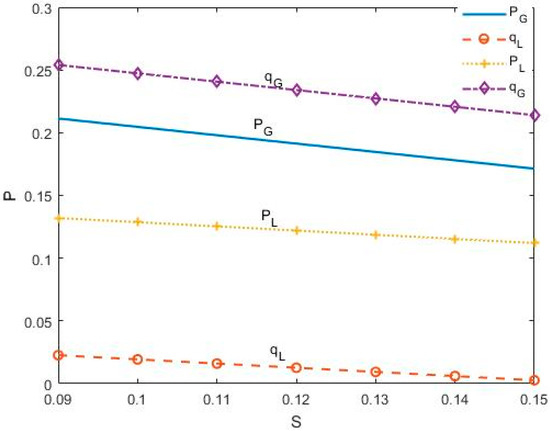

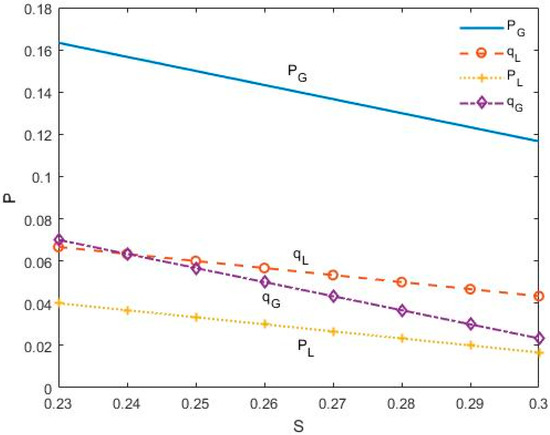

By numerical simulation, we can further test the relationship between the prices of two agricultural products. Assuming , , , we obtain the scope of green subsidy S: , If , subsidy S1 is 0.238, obviously point S1 does not exist. We used Matlab software to obtain the pricing strategies of organic agricultural product enterprises and conventional agricultural product enterprises at different subsidy levels, as shown in Figure 3. , which is to say, the pricing of two types of agricultural product enterprises is from high to low in the following order: the poaching price of organic agricultural products, the loyalty price of organic agricultural products, the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products, and the poaching price of conventional agricultural products. Thus, Proposition 2 is proved.

Figure 3.

Impact of subsidies on enterprise pricing ().

According to Proposition 2, when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is inferior, in order to stabilize existing loyal customer resources, organic agricultural product enterprises will give corresponding loyalty discounts to their loyal customers. However, the conventional agricultural product enterprises are in a strong position in the market at this time; therefore, they take charge of loyalty premium to loyal customers.

Proposition 3.

When the inherited market of organic agricultural products is in a state of fierce competition,, green subsidies will not affect the size of the relationship between the prices of two types of enterprises.

When , competition in the market is fierce, and the pricing strategies of both types of agricultural product enterprises are higher than the poaching price, , . There is no intersection between . If = , then . Set , if point S2 exists, it must satisfy the constraint condition in 3.3: . Therefore, . We know from , now τ has to satisfy both and . Therefore, point S2 does not exist, which means that when , there is no intersection between and . Similarly, the prices of organic agricultural products of similar brands in the market are higher than that of conventional agricultural products, , .

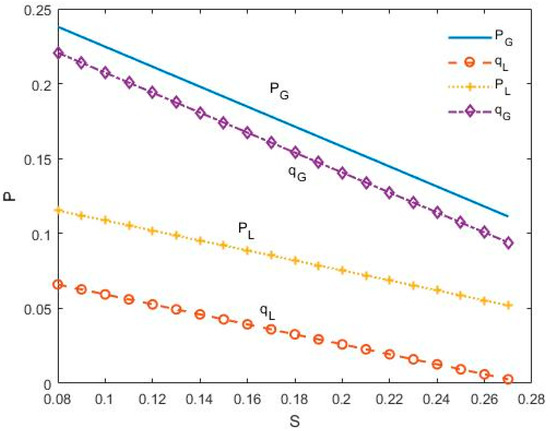

Assuming , , , we obtain the scope of green subsidy S: . If , subsidy S2 is 0.396, obviously point S2 does not exist. Similarly, through numerical simulation, we can obtain the pricing strategies of two types of agricultural product enterprises at this time, as shown in Figure 4, . At this time, the pricing of the two types of agricultural product enterprises is from high to low in the following order: the loyalty price of organic agricultural products, the poaching price of organic agricultural products, the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products, and the poaching price of conventional agricultural products. Thus, Proposition 3 is proved.

Figure 4.

Impact of subsidies on enterprise pricing ().

According to Proposition 3, when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is in a state of fierce competition, with the increase of green subsidies, in order to grab more market share, both agricultural product enterprises choose to give more discounts to poaching customers.

Proposition 4.

When the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, there is a threshold for green subsidies, when,; when,; when,.

When , the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, and the pricing strategies of the two types of agricultural product enterprises are as follows:, . At this time, organic agricultural product enterprises that have taken the dominant position will choose to charge loyalty premium to their loyal customers, while conventional agricultural product enterprises will choose to give loyal customers a certain discount to stabilize their existing market share from poaching. Comparing and , set , then . Set . If point exists, it must satisfy the constraint conditions in 3.3: , and ; therefore, . We know from , that point exists. Thus, when , there is a point , when , , ; when , , . When , , .

We can test this using a numerical simulation. Assuming , , , and , the scope of S is , is 0.24. Figure 5 shows the pricing strategies of the two types of agricultural product enterprises under different subsidy levels. Now, the price relationship between the two types of agricultural product enterprises is affected by the size of subsidies. If the green subsidy is relatively small , , that is, the pricing of the two types of agricultural product enterprises is from high to low in the following order: loyalty price of organic agricultural products, poaching price of organic agricultural products, poaching price of conventional agricultural products, and loyalty price of conventional agricultural products. When there are relatively large green subsidies , , that is, the pricing of the two types of agricultural product enterprises is from high to low in the following order: the loyalty price of organic agricultural products, the poaching price of conventional agricultural products, the poaching price of organic agricultural products, and the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products. In particular, the price of two types of agricultural products under green subsidies may be equal (when ), the loyalty price of organic agricultural products is higher than that of conventional agricultural products. Thus, Proposition 4 is proved.

Figure 5.

Impact of subsidies on enterprise pricing ().

According to Proposition 4, when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, if the subsidy is small, the poaching price of organic agricultural products will be higher than that of conventional agricultural products. With the increase in subsidies, the poaching price of organic agricultural products qG gradually decreases until it is equal to or even lower than the poaching price of conventional agricultural products qL, and the price advantage of conventional agricultural products over organic agricultural products will gradually disappear or even become a disadvantage. This also shows the support of green subsidies for organic produce.

When considering behavior-based pricing strategies, the lower price between loyalty price and poaching price represents the types of customers that enterprises want to compete for. Proposition 2 shows that when the initial market of organic agricultural products is inferior, the loyalty price of organic agricultural products is lower than the poaching price, and the poaching price of conventional agricultural products is lower than the loyalty price. In addition, with the increase of subsidies, the loyalty price of organic agricultural products is closer to the poaching price of conventional agricultural products, which means that the two types of enterprises compete for loyal customers of organic agricultural products more and more fiercely. Proposition 3 shows that when the initial market for organic agricultural products and conventional agricultural products is in a state of fierce competition, the poaching price of organic agricultural products is lower than the loyalty price, and the poaching price of conventional agricultural products is lower than the loyalty price. In addition, with the increase of subsidies, the poaching price of organic agricultural products is more and more close to the poaching price of conventional agricultural products, which means that the two types of enterprises compete for loyal customers of each other’s products more and more fiercely. Proposition 4 shows that when the initial market of organic agricultural products is dominant, the poaching price of organic agricultural products is lower than the loyalty price, and the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products is lower than the poaching price. In addition, with the increase of subsidies, the poaching price of organic agricultural products is closer to the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products, which means that the two types of enterprises compete for loyal customers of conventional agricultural products more and more fiercely. To sum up the above points, we can corollary 2.

Corollary 2.

When the inherited market of organic agricultural products is inferior, increases in subsidy increase the competition between the two enterprises for loyal customers of organic agricultural products; when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is in a state of fierce competition, increases in subsidy increase the competition between the two enterprises for the other loyal customers; when the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, increases in subsidy increase the competition for loyal customers of conventional agricultural products.

5. Impact of Green Subsidies on Enterprise Profits

Proposition 5.

When other conditions remain unchanged, the relationship between green subsidy S and the profits of two types of agricultural production enterprises is as follows: When,; when,; when,.

Set , represents the cost of producing organic agricultural products minus the additional consumption effect of organic agricultural products perceived by consumers with organic preferences. The higher the proportion of no preference consumers, the higher the . The higher the production cost of organic agricultural products, the higher the . The greater the additional utility of organic agricultural products perceived by consumers, the lower the . Because , when , the profits of enterprises producing organic agricultural products are less than those of conventional agricultural production enterprises. With the gradual increase in green subsidy, increases, , the difference in profits of enterprises producing two types of agricultural products reduces gradually. When , the profits of the two agricultural enterprises are equal.

When , green agricultural production enterprises obtain more profits than conventional agricultural production enterprises, and S is linearly positively correlated with the profit difference between the two types of enterprises. As S increases, increases: with the increase in government subsidies for organic agricultural product enterprises, the profit gap between the two types of enterprises gradually increases, and those producing organic agricultural products will gain more benefits. As S increases, both types of agricultural enterprises will choose to reduce prices. However, the price reduction of enterprises producing conventional agricultural products is only half of that of enterprises producing organic agricultural products. The market share of the organic agricultural product enterprise will increase, while that of the other will reduce, and the change in share will be equal. Therefore, with the increase in green subsidies, more consumers will buy organic agricultural products. At this time, both the prices and market share of conventional agricultural products will decrease, causing a fall in the profits of conventional agricultural production enterprises. Therefore, the profit gap between the two types of enterprises will gradually increase. As S decreases, decreases. When government subsidies to organic agricultural enterprises reduce, the profit gap between enterprises producing two types of agricultural products gradually decreases. When green subsidy is reduced, the market share of organic agricultural production enterprises decreases and that of conventional agricultural product enterprises increases. Although both types of enterprises will increase their overall prices, the costs of organic agricultural production enterprises will increase relatively due to the reduction of subsidies; therefore, the profit gap between the two types of enterprises will increase instead.

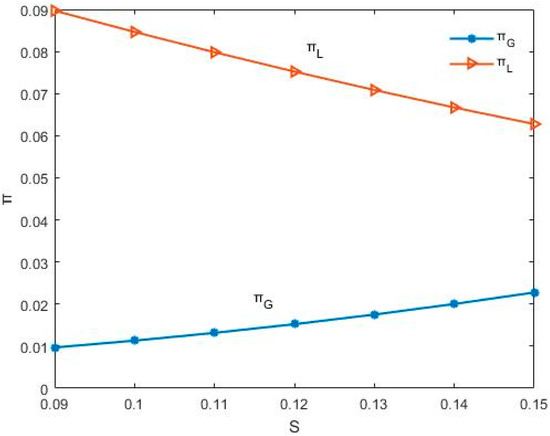

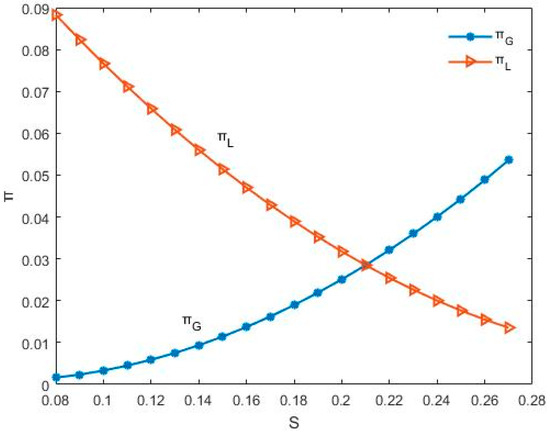

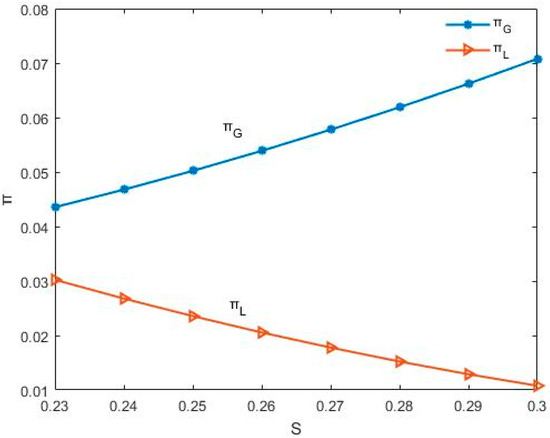

To better understand the impact of green subsidies on profits of the two types of agricultural enterprises, we assume , , and perform a numerical value analysis by selecting a representative value from each of the three different intervals of x0. Figure 6, Figure 7, and Figure 8, respectively, represent the inherited market of organic agricultural products as inferior, in a state of fierce competition, and dominant. From the graph, we find that the profits of organic agricultural enterprises increase with the increase in green subsidies, while that of conventional agricultural enterprises decreases with the increase in green subsidies. When the green subsidy is small (S < 0.21), the profits of organic agricultural enterprises is smaller than that of conventional agricultural enterprises. When , = = 0.0285, the profits of the two types of enterprises are equal. When the green subsidy is larger (S > 0.21), , it shows that when the green subsidy reaches a certain level, enterprises producing organic agricultural products will be more profitable than those producing conventional agricultural products, because of the large financial support, thus encouraging them to produce more organic agricultural products.

Figure 6.

Influence of subsidies on corporate profits ().

Figure 7.

Influence of subsidies on corporate profits ().

Figure 8.

Influence of subsidies on corporate profits ().

6. Conclusions

With increases in income and health awareness, more and more consumers in most developing countries are willing to try to buy organic agricultural products. At this time, there is indeed price competition between organic agricultural products and conventional agricultural products in the market. Compared with previous studies, which mainly analyzed the factors affecting the price of organic agricultural products, the consumer market we considered was different. The main research conclusions are as follows:

When the initial market of organic agricultural products is not dominant, green subsidies do not affect the size of all prices. When the inherited market of organic agricultural products is dominant, there is a threshold for green subsidies , when the amount of subsidy is less than the threshold, the order of price from big to small is: the loyalty price of organic agricultural products, the poaching price of organic agricultural products, the poaching price of conventional agricultural products and the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products. When the amount of subsidy exceeds the threshold, the order of price from big to small is: the loyalty price of organic agricultural products, the poaching price of conventional agricultural products, the poaching price of organic agricultural products and the loyalty price of conventional agricultural products.

When the initial market position of organic agricultural products is different, the types of competing customers are different between the two types of enterprises, and the intensity of competition will increase with the increase of subsidies.

When the green subsidy is less than the cost required to produce organic agricultural products minus the extra consumption effect perceived by organic preference consumers, the profit of organic agricultural enterprises is less than that of conventional agricultural enterprises. With the increase in government subsidies for organic agricultural products, the profits of organic agricultural enterprises increase, while those of conventional agricultural enterprises decrease. In particular, when the green subsidy is equal to the cost of producing organic agricultural products minus the extra consumption effect of organic preference perceived by consumers for consumption of organic agricultural products, the profits of the two types of agricultural enterprises are equal. Subsequently, with the continued increase in green subsidies, the profits of organic agricultural enterprises will be greater than the profits of conventional agricultural enterprises. Our research results will provide a decision-making reference for both types of enterprises to undertake behavior-based pricing, considering green subsidies, and contribute to improving the green subsidy policy, providing a reference for the government’s subsidy decisions.

This study does have some limitations. For example, future studies could consider the competition and cooperation behaviors of organic agricultural product sales in the context of “One Belt and One Road”. When considering environmental barriers, green barriers, tariff barriers or exchange rate risks, we discuss the behavior pricing and decision-making problems of agricultural production enterprises. However, agricultural products are of various types, which require different techniques of processing and storage. Therefore, when conducting behavioral pricing for different types of agricultural products, future studies should also consider their varying characteristics and categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology, K.L. and W.L.; Software, K.L.; Validation, K.L., Y.L. and W.L.; Writing, K.L., Y.L., W.L., and E.C.

Funding

This study was partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71540002; 71601074; 71420107027); general project of the Ministry of Education on humanities and social science research (11YJC790084).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hanrahan, C.E.; Zinn, J. Green Payments in US and European Union Agricultural Policy; Library of Congress (Congresional Research Service): Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Lopez, R.A.; He, X.; Falcis, E.D. What drives China’s new agricultural subsidies. World Dev. 2017, 93, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zong, Y.; Zhao, B. Analysis on policy evolution and policy system of EU agricultural green development support: Based on the policy evaluation of OECD. Agric. Econ. Prob. 2018, 5, 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Barański, M.; Rempelos, L.; Iversen, P.O.; Leifert, C. Effects of organic food consumption on human health; the jury is still out! Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1287333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancet, T. Organic food: Panacea for health? Lancet 2017, 389, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, C.; King, S.; Matsushima, N. Pricing with Cookies: Behavior-Based Price Discrimination and Spatial Competition. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 64, 5669–5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, R.B.; Cerqueira, S. Behaviour-Based Price Discrimination under Advertising and Imperfectly Informed Consumers; Nipe Working Papers; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, K.E.; Thomadsen, R. Behavior-based pricing in vertically differentiated industries. Manag. Sci. 2016, 63, 2729–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, T.; Shy, O.; Stenbacka, R. Behavior-Based Pricing and Market Dominance; Working Paper; Centre for Economic Policy Research Deutsche Zentralbibliothek für: Hanover, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, K.E. What types of switching costs to create under behavior-based price discrimination? Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2014, 37, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, R.B.; Reggiani, C. Elasticity of demand and behaviour-based price discrimination. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2014, 32, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S. Behavior and characteristic based price discrimination. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2018, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Bokelmann, W.; Gowdru, N.V.; Dias, G. Factors influencing consumers’ willingness to pay for organic fruits and vegetables: Empirical evidence from a consumer survey in India. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Gao, Z.; Zeng, Y. Willingness to pay for the “green food” in China. Food Pol. 2014, 45, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Shimizu, M.; Kniffin, K.M.; Wansink, B. You taste what you see: Organic labels bias taste perceptions. Food Qual. Preference 2014, 29, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Zhong, C.B. Do green products make us better people? Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suki, N.M. Green product purchase intention: Impact of green brands, attitude, and knowledge. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Wang, C.J. Do psychological factors affect green food and beverage behaviour? An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2171–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, M.; Jeger, M.; Ivković, A.F. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase green food. Econ. Res. Ekonom. Istraž. 2015, 28, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Mohammed Rafiul Huque, S.; Haroon Hafeez, M.; Noor Mohd Shariff, M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S.; Yang, I.S.; Choi, J.G. The roles of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in the formation of consumers’ behavioral intentions to read menu labels in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, A. Bringing green food to the Chinese table: How civil society actors are changing consumer culture in China. J. Consum. Cult. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, J.; Allès, B.; Péneau, S.; Touvier, M.; Méjean, C.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Dietary intakes and diet quality according to levels of organic food consumption by French adults: Cross-sectional findings from the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study Cohort Study. Pub. Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nina, M.; Louisem, H. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, M.; Mitelut, A.; Popa, E.; Stan, A.; Popa, V.I. Organic foods contribution to nutritional quality and value. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithspangler, C.; Brandeau, M.L.; Hunter, G.E.; Bavinger, J.C.; Pearson, M.; Eschbach, P.J.; Sundaram, V.; Liu, H.; Schirmer, P.; Stave, C.; et al. Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives? A systematic review. Ann. Int. Med. 2013, 158, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulet, J.M. Should we recommend organic crop foods on the basis of health benefits? Letter to the editor regarding the article by Barański et al. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1745–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.L.; Chen, B. Study on Dynamic Pricing of Perishable Asset under Subsidy. Ind. Eng. J. 2010, 13, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.H.; Huang, T.; Lei, M. Dual—Channel Recycling Model of Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment and Research on Effects of Government Subsidy. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 21, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Lei, M.; Deng, H.; Leong, G.K.; Huang, T. A dual channel, quality-based price competition model for the WEEE recycling market with government subsidy. Omega 2016, 59, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.Q. Decision research for dual-channel closed-loop supply chain under the consumer preferences and government subsidies. Syst. Eng. Theory Sz Pract. 2016, 36, 3111–3122. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, S.L.; Liu, J. The Influence of Government Subsidy Modes on the Decision of Bio-agricultural Products Supply Chai. East China Econ. Manag. 2017, 31, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).