1. Introduction

Highly diverse customer demand drives managers that are eager to know what customers think and want. Customer orientation is an effective way to gain sustainable profit for the company [

1,

2]. Contrary to selling orientation, customer orientation emphasizes meeting the customers’ needs and avoids sacrificing customer benefit for long-term customer relationships [

3], which usually leads to high job performance in a sustainable way [

4,

5].

Previous research dominantly focuses on the sustainable job outcome of customer orientation, such as job performance [

4,

5]; less is known about suitable environments of customer orientation, which are critical for salespeople to practice their customer orientation. Furthermore, previous studies stress the importance of functional customer orientation, which is defined as salespeople acting in the role of businessmen, identifying needs and explaining and recommending products to customers [

1,

6], but place less emphasis on relational customer orientation, which is defined as salespeople acting as friends building personal relationships with customers [

7,

8]. Maintaining a close relationship with customers is very important for salespeople, especially in China, because Chinese individuals’ relationships (i.e., guanxi) have instrumental attributes, and products in China are usually sold on the basis of friendship [

9]. Additionally, previous studies found that salespeople’s customer orientation has mixed effects on performance outcomes [

10,

11], and functional (vs. relational) customer orientation produces a different effect on the creativity of salespeople [

8]. Therefore, we specifically classify customer orientation into functional customer orientation and relational customer orientation in order to locate its different influences.

Implementing customer orientation requires plenty of resources [

3,

12]. The biggest challenge is not whether to choose the customer orientation strategy or not, but how to make customer orientation sustainable, to balance the input resources and the output of performance, and to create a sustainable environment for customer orientation operation. Due to stressful job requirements, salespeople are very susceptible to losing functional or emotional resources. Based on conservation of resource theory [

13], individuals have natural instincts to preserve and protect resources (e.g., personal mental resources and workplace resources), especially when those valued resources are at risk of being lost or are already lost. When losing resources or not getting enough supplementation after investing resources, people feel mentally stressed [

14]. Long lasting resource deficits lead to emotional exhaustion, a serious affective and chronic type of work strain [

15,

16], which decreases service performance and customer satisfaction [

14,

17].

Considering salespeople’s high sales quota and heavy mental resource usage, it is critical to consider the level of emotional exhaustion of salespeople when managers expect more sustainable outcomes of salespeople’s customer orientation. Previous research has found that customer orientation positively influenced salespeople’s job performance [

18], increased customer purchase likelihood, and increased customer relationship continuity [

19]. However, researchers also found that higher customer orientation does not always produce higher performance; instead it is an inverted U-shaped effect [

3,

12]. It may result from situational moderating factors (e.g., product individuality and supplier price positioning) [

12] and improper use of cross-sectional performance [

20]. Compared to job performance, adaptive selling behavior is a better way to measure the outcome of customer orientation, because it represents salespeople using extra resources to adopt different influence tactics for different kinds of customers [

21] and a strong prediction index of customer satisfaction and future interaction [

22,

23].

Therefore, our research is aimed at finding out how functional/relational customer orientation of salespeople affects their adaptive selling behavior, and how emotional exhaustion moderates these main effects. We collected 282 valid questionnaires from front-line salespeople in 16 different companies in China to address these questions. Our research will contribute to the studies of sustainable company profits and sustainable sales resources in the future.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

To test our hypotheses, we collected data by delivering self-administered questionnaires to front-line salespeople. We first contacted the sales managers and senior human resource executives of some companies via telephone and email, expressed our intention, and asked for their permission. We gave them a brief introduction to this investigation process and told them we required their assistance. Some companies’ CEOs or managers knew our authors, which facilitated acceptance. At last, a total of 16 companies agreed to participate; they included companies from furniture, household appliances, finance, and software industries, among others. These companies’ headquarters are in the Guangdong province in China. The salespeople involved in the survey are distributed throughout Guangdong, Anhui, Fujian, and other places.

Before formal investigation, we used G*Power software to determine our sample size [

44]. According to a meta-analysis of Frank and Park (2006) [

45], the average effect size involving the relationship between customer orientation and adaptive selling behaviors was 0.26. Using the software, we found that, given an α error probability of 0.05, power is 0.80. Results showed that we should investigate at least 119 salespeople for a one-dimensional study; therefore, for a both two-dimensional study, we needed more than 238 salespeople. Furthermore, according to Comrey (1988) [

46], a sample size of 200 is good for an ordinary factor analysis with 40 or fewer test items. We had fewer than 40 test items in the questionnaires. We prepared to collect more than 250 samples to adequately power the key customer orientation (functional/relational) × emotional exhaustion interaction.

Because front-line salespeople usually work in different sales sections and not always indoors, it is hard to investigate all salespeople at the same time. We randomly selected several selling departments of the company from a list of all selling departments, and we then visited the chosen departments. With the help of department managers, we acquired a list of salespeople’s names. For those who stayed on site, we distributed and retrieved questionnaires as soon as salespeople filled them in. For those who were not on site, we contacted them by online survey. We sent the online website link to the managers, let them transmit the website links to the rest of the salespeople, and asked them to fill it in. During the process, we promised that the survey data would only be used for academic research, and we would keep the information anonymous.

For data collected on the site, we sent out 250 questionnaires in total, received 225 back, excluded questionnaires with incomplete data and obvious errors, and ended up with 211 valid questionnaires. For data collected online, we sent out 80 questionnaires and received 71 valid questionnaires. Therefore, the final total was 282 questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 85.5%.

Table 1 presents demographics of the sample.

3.2. Measures

In this study, we translated English scales into Chinese type. All items were measured by a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “highly disagree” to 7 = “highly agree”. We have listed the measurement items in

Appendix A.

Functional customer orientation. We measured functional customer orientation using a nine-item scale that was adapted from Homburg et al. (2011) [

7]. Sample items are as follows: “I ask my customer about their specific performance requirements” and “I focus on functional information which is especially relevant for my customers.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.88.

Relational customer orientation. We measured functional customer orientation using a four-item scale that was also adapted from Homburg et al. (2011) [

7]. Sample items are as follows: “In sales conversations, I establish a personal relationship with my customers” and “I often point out things I have in common with my customers (e.g., common interests, experiences, and attitudes).” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.83.

Emotional exhaustion. We measured emotional exhaustion using a four-item scale that was adapted from Maslach and Jackson (1981) [

37]. Sample items are as follows: “I feel emotionally drained from my work” and “I feel used up at the end of the workday”. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.83.

Adaptive selling behavior. We measured adaptive selling behavior using a three-item scale that was adapted from Piercy et al. (2009) [

47]. Sample items are as follows: “I am flexible in sales approaches used” and “I adapt sales approaches from one customer to another.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.93.

Control variables. We controlled salespeople’s age, gender, education, working tenure, and tenure with their superior in this study. We measured those control variables using a dummy variable, which codes male as “1” and female as “2”; age is labeled from “1” to “7”; education is labeled from “1” to “5”; work tenure is labeled from “1” to “5”; work tenure with superior is labeled from “1” to “5.” The descriptive statistics analysis of these control variables is shown in

Table 1.

3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Inter-Correlations between Variables

We use SPSS 22.0 to analyze our data. The mean, standard deviation, and correlation of variables are reported in

Table 2. In

Table 2, functional customer orientation is significantly positive with respect to adaptive selling behavior (

r = 0.66,

p < 0.01), relational customer orientation is significantly positive with respect to adaptive selling behavior (

r = 0.46,

p < 0.01), and emotional exhaustion is significantly negative with respect to adaptive selling behavior (

r = −0.19,

p < 0.01).

3.4. Reliability and Validity

We use Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) to measure the reliability of scale. According to Cortina (1993) [

48], Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.70 is acceptable; all Cronbach’s alpha values of our constructs are higher than 0.80, showing good reliability. In addition, according to Hair et al. (2013) [

49], composite reliability greater than 0.70 is acceptable; all our CR values of construct meet this standard.

We also assessed scale’s validity, using convergent validity and discriminate validity as indices. First, we computed each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) value to measure convergent validity and found that all AVE values are higher than 0.50, suggesting that these constructs have good convergent validity, according to the standard of Fornell and Larcker (2010) [

50]. We show Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and AVE in

Table 3.

Following Fornell and Larcker (2010) [

50], we use a square root of AVE greater than the inter-construct correlation to measure discriminant validity. As seen in

Table 4, the square root of the AVE value is greater than the correlation of each construct, showing our scale has good discriminate validity.

Lastly, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis to confirm that our four-factor model is the most suitable for analysis. We used Amos 22.0 to conduct confirmatory factor analysis, linked each item with its intended construct, and freely estimated the covariance among constructs. Usually, the acceptable standard for SRMR is less than 0.08 [

51], for X

2/df is less than 3.0 [

52], for GFI/NFI/TLI/CFI is more than 0.90 [

53], and for RESEA is less than 0.70 [

54]. From

Table 5, we can see only the four-factor model is the best fit, meeting all requirements of cutoff criteria.

4. Results

We used several hierarchical linear regressions to verify our hypotheses. Those results are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7. First, we standardized all control variables, independent variables, and moderator variables, and we then used SPSS to verify our hypothesis. At last, we used the bootstrap process of Hayes to test our moderator effect.

Furthermore, we used Harman’s single factor method to show our data does not have a serious common method bias. We loaded all variables into the factor analysis, but constrained the number of factor to “1.” The first component of the total variance explained is 37.98%, less than 50%, showing that there is no substantial common method bias presence in the data [

55].

As seen in

Table 4, in Model 1, we first entered standardized control variables including age, gender, education, working tenure, and working tenure with superior. In Model 2, we entered standardized independent and moderator variables. It shows functional customer orientation is positively related to adaptive selling behavior (β = 0.704,

p < 0.001), supporting H1. In Model 3, we entered standardized functional customer orientation × emotional exhaustion to test its moderating effect and found that the interaction of functional customer orientation and emotional exhaustion reveals a significant impact on adaptive selling behavior (β = −0.156,

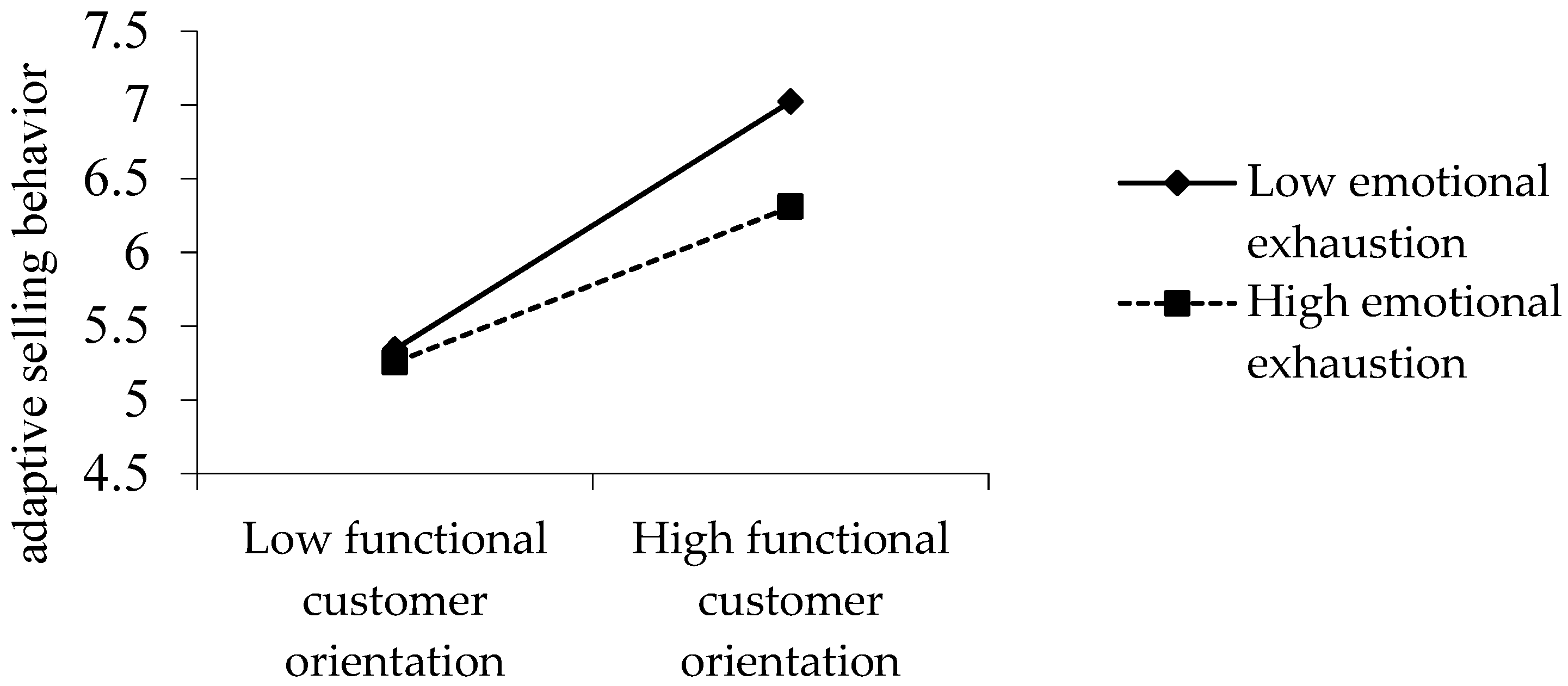

p < 0.05), supporting H3. Furthermore, we used the Hayes process to test our moderator model, bootstrapping 2000 samples. The result supports H1, that higher functional customer orientation leads to more adaptive selling behavior (β = 0.6830, SE = 0.0651, 95% CI = [0.5548, 0.8111]), and H3, that emotional exhaustion disrupts the positive relationship between functional customer orientation and adaptive selling behavior (β = −0.1564, SE = 0.0746, 95% CI = [−0.3033, −0.0095]).

Figure 2 shows the moderating effect of emotional exhaustion on the relationship between functional customer orientation and adaptive selling behavior. We plus/minus one standard deviation from the mean emotional exhaustion score, in order to represent high/low emotional exhaustion. We used the same method to calculate the high/low functional customer orientation.

Consistent with the steps above, we also conducted hierarchical linear regression analyses and bootstrapped the process to test Hypotheses 2 and 4.

In

Table 7, we can see relational customer orientation is positive related with adaptive selling behavior in Model 5 (β = 0.40,

p < 0.001), supporting H2. In Model 6, the interaction of relational customer orientation and emotional exhaustion reveals a significant impact on adaptive selling behavior (β = −0.08,

p < 0.05), supporting H4. Furthermore, we also used Hayes’s process to test our moderator model, bootstrapping 2000 samples. The result supports H2, that higher relational customer orientation leads to more adaptive selling behavior (β = 0.5064, SE = 0.0602, 95% CI = [0.3879, 0.6250]), and H4, that the emotional exhaustion disrupts the positive relationship between relational customer orientation and adaptive selling behavior (β = −0.1660, SE = 0.0693, 95% CI = [−0.3025, −0.0295]).

Figure 3 shows the moderating effect of emotional exhaustion on the relationship between relational customer orientation and adaptive selling behavior. We plus/minus one standard deviation from the mean emotional exhaustion score in order to represent high/low emotional exhaustion.

5. Discussion

5.1. Results

This study examines when customer orientation of salespeople cannot sustainably lead to a positive job outcome. We first identified the relationship between functional/relational customer orientations with the adaptive selling behavior of salespeople, and then investigated whether emotional exhaustion moderates the main effect. Results of this study are as follows.

First, we show that not only functional customer orientation but also relational customer orientation produces more adaptive selling behavior. Second, this positive effect will be moderated by salespeople’s emotional exhaustion level. When salespeople’s emotional exhaustion level is high (vs. low), the positive effect between functional/relational customer orientation and adaptive selling behavior is substantially weakened.

5.2. Theory Contribution

First, we answer the calling of Homburg et al. (2011) [

7] of more research on both types of customer orientation. They classified customer orientation into functional customer orientation and relational customer orientation according to their role in business. We found not only functional customer orientation but also rational customer orientation contributes to positive job outcomes, such as adaptive selling behaviors. Furthermore, our research explains why higher customer orientation leads to higher job performance [

11,

18], partly because higher customer orientation increases adaptive selling behaviors when salespeople interact with customers as shown in this paper.

Secondly, we also answer the challenge of discovering why salespeople’s customer orientation does not always result in higher job outcomes. Our research shows it is influenced by the sustainability of salespeople’s resources. Previous studies have shown that higher salesperson customer orientation does not always produce higher job performance [

12,

56]; researchers have found contextual factors (e.g., product importance/competitive intensity) [

12], a sales manager’s ability to perceive emotions [

3], and low job autonomy [

57] influence the effect of salespeople’s customer orientation on sales performance, impeding customer orientation from producing sustainable positive outcomes. However, we think it is also important to focus on the sustainable sales resources of salespeople because salespeople need many resources to operate their customer orientation mindset. Our research fills this gap and finds that a low level of salespeople’s emotional exhaustion is a very critical factor in letting customer orientation take effect.

5.3. Implications

First, managers should put the same weight on developing salespeople’s functional and relational customer orientation. In salespeople’s training, companies usually put more stress on salespeople’s functional customer orientation, such as ensuring salespeople have a wide knowledge about products and are patient when answering customer’s questions, and they have lots of qualifying tests to make sure salespeople master enough knowledge. However, our research shows relational customer orientation also plays an important role in job behaviors, so measuring and testing salespeople’s relational customer orientation should also be taken into consideration in training, and this would result in more sustainable profits.

Second, managers should focus on building a sustainable operational resource environment for salespeople and eliminate the factors that lead to the emotional exhaustion of sales staff, such as complicated reimbursement processes, a vague job role, indifferent job support atmosphere, etc., to provide a sustainable implementation environment for sustainable customer-oriented thinking. Managers cannot blindly emphasize customer orientation of salespeople without offering supporting resources.

5.4. Limitations and Future Study Suggestions

First, because of the high staff mobility of salespeople and the wide range of this investigation between different companies, we used the cross-section data and self-administered questionnaire. We tested the variance inflation factor (VIF) and found it was less than 3, which meant it was acceptable for analysis and had no serious multicollinearity problem. However, we do recommend researchers take the manager-rated performance for salespeople and use a longitude study in the future. Furthermore, the correlation values between the emotional exhaustion with others are at a low degree, and we guess that this may be because salespeople were motivated to manage their self-image, and did not completely trust that researchers would keep the information anonymous. Researchers can use other administration methods to value the level of emotional exhaustion of salespeople in the future.

Second, researchers can further explore the difference effect between functional versus relational customer orientation and find their different influences on job outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, job turnover rate, and customer loyalty). In addition, researchers can investigate other moderate variables that may have positive effects on the relationship between functional customer orientation and job outcomes, but have a negative or no effect on the relationship between relational customer orientation and job outcomes.

Third, researchers can also focus on the dark side of customer orientation. Because customer orientation requires that salespeople care more about customer well-being and invest more resources in them, it not only increases the job burden of salespeople but also results in an excessive customer orientation, leading salespeople to substantially benefit customers but harm the company’s interests, e.g., collaborating with customers to cheat on the salespeople’s company and sending excessive gifts to customers. To this effect, Leo and Russell-Bennett (2014) [

58] have already developed a multidimensional scale of customer-oriented deviance, so future studies can explore with which type of customer orientation and in which situations salespeople will perform such deviant customer orientation behavior.

Fourth, researchers can investigate how the customer orientation of salespeople influences value co-creation with customers and which type of customer orientation has a greater effect on customer participation behavior. Researchers found that customer orientation can increase the willingness of customers to share competitor information [

28] and customer citizenship behavior [

59], which are both types of customer value co-creation behavior [

60]. Therefore, we suggest that future researchers determine which types of customer orientation can produce the various types of customer value co-creation behaviors.