1. Introduction

In recent years, related concepts such as collaborative consumption, sharing economy, peer-to-peer economy, use of economy, redistribution of market, and on-demand economy have gained increasing attention. Among them, collaborative consumption is the concept that focuses on the specific aspects of consumption.

Different papers give different definitions of collaborative consumption [

1,

2]. To describe the collaborative consumption completely, this paper considers aspect of collaborative consumption as comprehensively as possible based on previous papers, and defines collaborative consumption as: a kind of consumption pattern that consumers access, give, and share the right to use the same units of goods or services by sharing, exchanging, bartering, trading, and leasing using the Internet and mobile Internet platform to obtain monetary income or other compensation. Collaborative consumption as defined in this paper stresses drawing on the same units of material goods or services to share the right to use, i.e., the benefits of one material good or service unit are split among several individuals [

3]. For instance, the consumption pattern of consumer to consumer is not within the definition of collaborative consumption because consumers who own the goods do not share their goods that they use themselves but offer another “unit of goods”, and they exchange the ownership of the goods instead of the right to use it. The fundamental difference between collaborative consumption and traditional consumption patterns is that collaborative consumption emphasizes the same units of goods or services and the right to use products or services rather than owning them.

With the information technology, Web 2.0 and social networks, the industry scale and market size of collaborative consumption are developing so rapidly that it can no longer be ignored. According to the report of the Data Research Center, the scale of China’s sharing economy industry reached 539.48 billion yuan (79.84 billion dollars) in 2017, with a growth rate of 41.6% [

4]. In the “Annual Report on Sharing Economic Development in China”, the transaction volume of China’s sharing economic market in 2017 was about 4.9 trillion yuan (725.2 billion dollars), an increase of 47.2% over the previous year [

5].

However, since the development of collaborative consumption is still in its infancy, it has inevitably encountered some problems, which mainly reflect the following three aspects: First, the single way that collaborative consumption enterprises compete for users, namely, long-term low-price strategy, will bring uncertainty to the survival and development of the enterprise. Second, the blind investment of capital in collaborative consumption is hard to bring profit to venture capital enterprises and collaborative consumption enterprises, which is harmful to the sustainable development of the entire industry. Finally, the current situation that some enterprises develop rapidly and go bankrupt rapidly has caused a waste of resources.

The reason for the above problems is that the identification of user needs is unclear. The single marketing strategy of enterprises is due to the lack of exploration of the deep-seated needs of users; the blind investment of capital investment is reflected in the fact that the investment enterprises do not grasp the real needs of users; and the fundamental reason for the unsustainable development of some collaborative consumption enterprises is incorrectly treating the user’s incidental needs as necessary needs.

This paper argues that, to understand the necessary and real needs of collaborative consumption users, it is necessary to find the motivation for users to use collaborative consumption products or services from the user’s perspective. The question is, in such a user-oriented society, what kind of motivation leads users to choose one collaborative consumption enterprise rather than others, which is an urgent question that needs to be solved and is still pending. Understanding the motivation of users to participate in collaborative consumption deeply and finding the key points of users’ needs effectively are the basis for achieving sustainable development in collaborative consumer enterprises and even the entire industry.

2. Research Model and Hypotheses

2.1. Characteristics of Collaborative Consumption

This paper summarizes the following five distinctive characteristics of collaborative consumption based on existing studies. (1) Economy: Collaborative consumption based on the right to use can let participants gain benefits or save costs [

6]. This consumption pattern emphasizes the right to use so that two or more individuals involved in collaborative consumption can share costs, thus reducing consumption and saving costs. Freiberg et al. [

7] found the P2P leasing market can improve consumer welfare. (2) Technology: Collaborative consumption emerges as a high-tech phenomenon [

8]. Belk [

6] thought sharing activities are facilitated by the Internet. Only through the Internet or mobile Internet technology can we make previously impossible, cross-regional, peer-to-peer communication possible. (3) Ecology: Collaborative consumption is a kind of economic form that promotes sustainable development and is also a kind of consumer culture that save resources [

9]. Amasawa et al. [

10] found it can reduce 1.8% of greenhouse gas emissions and 16% of resource use by a behavioral shift from home washing to laundromat use. Collaborative consumption increases the surplus or limits the use of resources, thereby reducing waste. (4) Society: The community can be established by sharing activities [

11]. Users can have the opportunity to make friends and build meaningful relationships by participating in collaborative consumption, and collaborative consumption can connect dispersed individuals to form a community. Belk [

12] argued that sharing activities tends to make people feel like they are part of like-minded group. (5) Institution: Compared with the rapid development of collaborative consumption, the related policy system is far from perfect. Barnes and Mattsson [

13] found that “the lack of targeted public sector support” is an important factor hindering the development of collaborative consumption. For instance, some shared bicycle companies in China use the deposits paid by users without authorization and supervision, which makes the user deposit difficult to return, triggering a series of social problems. Currently, the People’s Bank of China and Ministry of Transport of China are trying to intervene in the supervision of deposit incidents.

2.2. Self-Determination Theory

There has been a long history of the user decision-making and adoption behavior. Until now, most studies are based on rational behavior theory and planned behavior theory. Among them, the most widely used is the technical acceptance model (TAM) model in rational behavior theory [

14,

15]. Except that, some scholars also use the theory of effect and the theory of value-based adoption model [

16,

17]. However, considering user’s intention and behavior only from the perspective of rationality and value is limited.

Self-determination theory believes that it is necessary to consider the motivation from rational and irrational level, and user’s decision-making is driven by both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. In the original definition, extrinsic motivation refers to people performing certain activities to obtain some separable result, and intrinsic motivation refers to people doing certain activities for inner pleasure and satisfaction [

18]. Therefore, to better interpret the motivation to participate in collaborative consumption of users, this paper uses the self-decision theory as the theoretical basis.

The studies based on self-determination theory are divided into two types: one is to directly use perceived usefulness as extrinsic motivation, and the enjoyment as intrinsic motivation to explore the influence on consumer behavioral intention [

19,

20] and the other is to find different motivations based on the field of research, and classify them into extrinsic motivations or intrinsic motivations according to their characteristics [

21,

22].

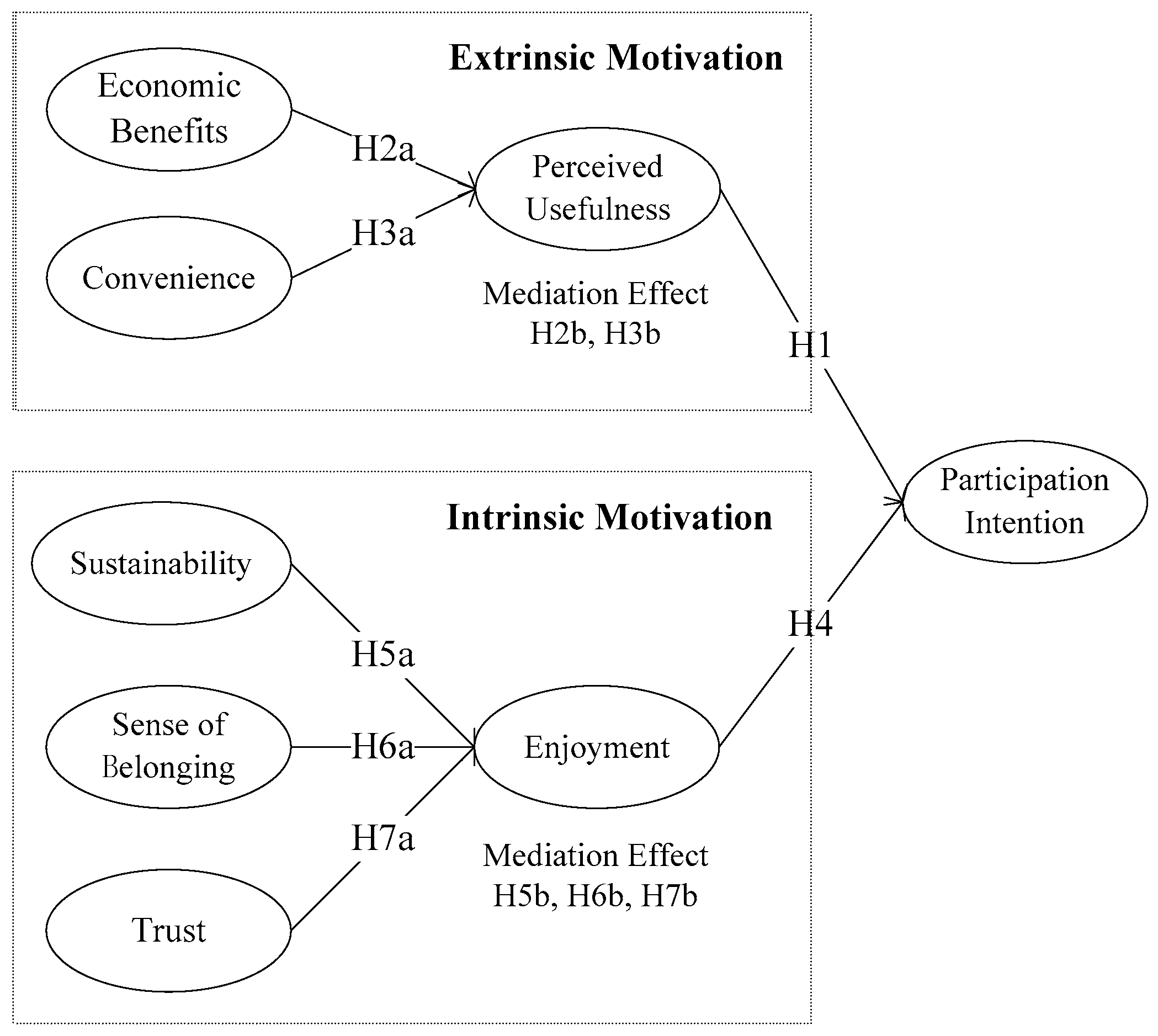

Considering the characteristics of collaborative consumption, this paper proposes the motivations for users to participate in collaborative consumption from rational and irrational level, namely economic benefit, convenience, sustainability, sense of belonging and trust. Combining the two above-mentioned research models of self-determination theory, this study used the motivations related to the characteristics of collaborative consumption as key antecedents of perceived usefulness and enjoyment to explore the internal mechanism of motivation. Among them, economic benefit represents a certain instrumental value, and convenience represents a kind of functional value, which both belong to the separable result that users can obtain, thus economic benefit and convenience were classified into extrinsic motivations and served as antecedents of perceived usefulness. Sustainability, sense of belonging and trust are more related to the satisfaction of different psychological needs, thus this study classified them into intrinsic motivation and as antecedents of enjoyment. Based on the above explanation, considering the context of this study, extrinsic motivation is defined as committing an action because of its perceived usefulness in achieving instrumental and functional value, and intrinsic motivation is defined as committing an action because of enjoyment related to the satisfaction of different psychological needs.

2.3. Extrinsic Motivations

Perceived usefulness is defined as the extent to which users believes that using collaborative consumption product or service can increase the efficiency of work or life [

23]. Möhlmann [

24] showed through empirical research that utility has a positive effect on user satisfaction with a sharing option and likelihood of choosing a sharing option again. Logically, people will use a product that helps them work and live better. The more useful users perceive the collaborative consumption product or service, the more they will intend to participate. This led to the following hypothesis:

H1: Perceived usefulness has a positive effect on the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

Economic benefit is defined as the extent to which users perceive that participating in collaborative consumption can provide money or reduce cost. Tang et al. [

25] found that personal gains positively affected the perceived usefulness of users in collaborative consumption. Bardhi and Eckhardt [

26] conducted a qualitative study of the access economy for cars and found consumers largely motivated by self-interest and utilitarianism. Collaborative consumption emphasizes the right to use, so that the providers of the product or service can obtain economic benefit or reduced costs by selling the short-term ownership of the product or service, while the recipients reduce their cost of having to own an item. The higher is the perceived economic benefit of the user, the higheris the perceived usefulness and the greater is intention to participate. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

H2a: Economic benefit has a positive effect on perceived usefulness.

H2b: Perceived usefulness is a mediator between economic benefit and the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

Convenience refers to the extent of time and effort savings perceived by a user. Moeller et al. [

27] found that users’ preference for non-ownership consumption patterns was significantly affected by being “convenience-oriented”. Collaborative consumption emerges as a high-tech phenomenon; its patterns are mostly composed of online and offline parts, namely the use of online applications or mobile applications, as well as the searching and matching of offline resources. Users can find the resource they need and how to get them at anytime and anywhere through a variety of technologies, instead of relying on traditional channels, which saves time and effort and facilitates the daily life of users. Such convenience is likely to have a positive impact on perceived usefulness and intention to participate in collaborative consumption. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

H3a: Convenience has a positive effect on perceived usefulness.

H3b: Perceived usefulness is a mediator between convenience and the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

2.4. Intrinsic Motivation

Enjoyment refers to the extent of inner pleasure and satisfaction that a user perceives in a certain consumption activity. Barnes et al. [

28] and Hamari et al. [

29] suggested that enjoyment is significantly positively correlated with the intention of users to participate in collaborative consumption. As an emerging consumption model, collaborative consumption has quickly attracted the attention of people from all walks of life. For today’s consumers, when a new product or service meets its functional needs, they pursue emotional pleasure. When they think that a product or service gives them a higher level of pleasure, they are more likely to use the product or service. This led to the following hypothesis:

H4: Enjoyment has a positive effect on the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

Sustainability is defined as the extent to which users perceive that participating in collaborative consumption can save resources and reduce consumption. Hamari et al. [

29] empirically demonstrated that sustainability significantly affects users’ behavioral intentions by affecting users’ attitudes toward collaborative consumption. Tussyadiah [

30] found that sustainability is one of the drivers of user engagement in collaborative consumption through exploratory study. However, Moeller et al. [

27] found that “environmentalism” does not affect users’ preference for non-ownership consumption. When an individual feels that collaborative consumption can save resources and reduce consumption, his/her demand for “altruism” is satisfied, and the individual tends to perceive that he/she has made some contribution to others, society, and even the natural world, thus extent of pleasure perceived is higher, which leads to greater intention to participate. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

H5a: Sustainability has a positive effect on enjoyment.

H5b: Enjoyment is a mediator between sustainability and the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

Sense of belonging is defined as the extent to which users consider themselves belonging to a certain group or a certain community. Albinsson and Perera [

11] believed that individuals involved in collaborative consumption have established communities through shared activities. Vaskelainen and Piscicelli [

31] found that offline communities are as important as online communities. In C2C-style collaborative consumption, direct human-to-human interaction and experience in sharing goods create and maintain social relationships with others, while, in B2C-style collaborative consumption, although there is no direct relationship between users, they may still think that they are part of a community that uses a certain common product, and this sense of community will make them feel psychologically fulfilled, happy and satisfied, thus increasing their intention to participate. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

H6a: Sense of belonging has a positive effect on feelings of enjoyment.

H6b: Feelings of enjoyment is a mediator between sense of belonging and the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

Trust is a psychological expectation or subjective desire that participants believe that other participants will perform their obligations in accordance with their own expectations [

32]. Because collaborative consumption is an emerging form of consumption and lacks complete institutional norms, users have suspicion about other participants in collaborative consumption, which affects the security required by users. Tussyadiah [

30] pointed out that lack of trust is a deterrence for users to participate in collaborative consumption in the tourism environment. Barnes et al. [

28] found that trust is not a factor that significantly affects people’s intention to participate in collaborative consumption. The general objective of trust aims at a good feeling; trust will reduce the anxiety and worry in the process of participation for users, and the more secure the user feels, the easier they will meet their inner needs. This suggests that trust is associated with enjoyment. Trust is likely to have a positive impact on the feelings of enjoyment and the intention to participate. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

H7a: Trust has a positive effect on feelings of enjoyment.

H7b: Feelings of enjoyment is a mediator between trust and the intention to participate in collaborative consumption.

Based on the above hypotheses, the research model proposed in this paper is shown in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Scales

This study adapted measurement items from existing self-determination theory scale, collaborative consumption scale, and supplemented them to capture bicycle sharing user behavior. The survey was delivered to respondents in China. Because it is a survey in China, whereas most of the items are based on English literature, for the accuracy of the description, after translating items into Chinese, this study back-translated them into English for comparison. The English version of the scale items are shown in

Table 1. This study used five-point Likert scales; respondents were asked to answer according to their actual perception and experience, by selecting: (1) “strongly disagree”; (2) “disagree”; (3) “neutral”; (4) “agree”; or (5) “strongly agree”.

3.2. Data Collection

In this study, data were collected using online and offline surveys of bicycle sharing users between October and December 2017. According to the address of the online questionnaire filled in by users (website background statistics), the questionnaire covered 22 provinces of China including Xi’an, Beijing, Shenzhen, Yunnan, Chongqing, Zhejiang and Shanghai. We collected 412 questionnaires in total with 373 useful responses. The characteristics of the final sample are shown in

Table 2. Male and female were evenly split. The median age was 18–25 years. The respondents were educated, with around 82.0% of the total sample holding an undergraduate degree. The proportion of samples using bicycle sharing for 7–12 months was the highest at 22.0%, and the proportion of not using ones was the lowest at 13.1%. Overall, 71.8% of users chose Ofo, which was the largest proportion, while the second largest was Mobike, with 60.1%. Ofo and Mobike are bicycle sharing companies founded in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

4. Results

The Shapiro–Wilk test result shows that the p values of the 22 measured variables were all less than 0.05. In addition, the absolute values of the skewness of 16 variables were between 0.51 and 1.225, and the absolute values of the kurtosis of 11 variables were between 0.51 and 2.28. Thus, the data for most variables did not match the normal distribution. Thus, this study tested partial least squares path modeling (PLSPM), a variance maximization technique for structural equation modeling (SEM) that makes no distributional assumptions for data. SmartPLS 3.2 (SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) was the main statistical tool in this study.

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the reliability, discriminant validity and convergent validity of the constructs.

Table 3 shows that all standard loadings of measurement items were above 0.7 and significant at the 0.001 level, and metrics for the final scales revealed that the Cronbach’s Alpha scores and composite reliability (CR) values were greater than 0.7 [

34]. The results support scale reliability.

Table 4 shows that the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) were greater than 0.71 (i.e., AVE was above 0.5), which means that the scale had good convergent validity.

Table 4 also shows the largest correlation coefficient (0.734) was lower than the smallest square root of AVE (0.792), supporting discriminant validity of the scale.

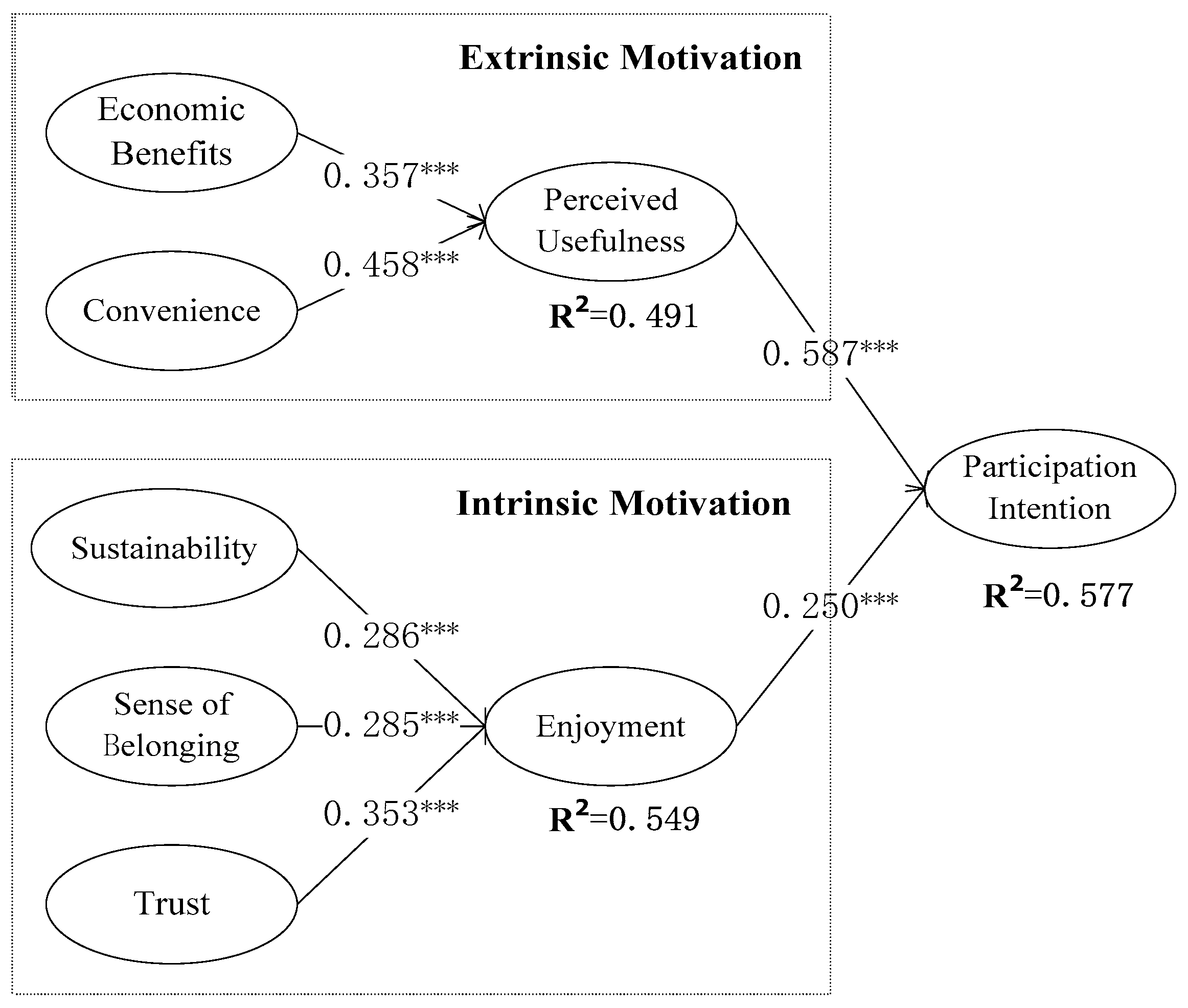

Figure 2 reports standardized regression coefficients in the research model. All of them were positive and significant at the 0.001 level, supporting hypotheses H2a, H3a, H5a, H6a, and H7a. In addition, the R-squared values indicated that the model explained most of the participation intention variation.

This study used a multi-level regression model to test the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and enjoyment. First, economic benefit, convenience, sustainability, sense of belonging and trust were used as independent variables; participation intention was used as the dependent variable; and the regression coefficient was represented by

c. Second, economic benefit and convenience were used as independent variables; perceived usefulness as dependent variable, and sustainability, sense of belonging and trust are respectively used was used as the independent variables; enjoyment was used as the dependent variable; and the regression coefficient was represented by

a. Finally, economic benefit, perceived usefulness, convenience, perceived usefulness, sustainability, enjoyment, sense of belonging, enjoyment, trust, enjoyment were used as independent variables; participation intention was used as the dependent variable; and the regression coefficient were represented by

c’ and

b. The results of testing the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and enjoyment are shown in

Table 5, and support hypotheses H2b, H3b, H5b, H6b, and H7b.

The results are shown in

Table 5. First, in Model 1, the regression coefficient (

c) of the independent variable to the dependent variable was significant, that is, economic benefit, convenience, sustainability, sense of belonging and trust had significant positive effects on participation intention (

p < 0.001). Second, in Model 2, the regression coefficient (

a) of the independent variable to the mediation variable was significant. Economic benefit and convenience had significant positive effects on perceived usefulness (

p < 0.001); and sustainability, sense of belonging and trust had significant positive effects on enjoyment (

p < 0.001). Third, in Model 3, when the independent variable and the mediation variable regressed the dependent variable at the same time, the regression coefficient (

b) of the mediation variable was still significant, but the regression coefficient (

c’) of the independent variable was significantly reduced or not significant. In addition, the coefficient of sense of belonging to participation intention was no longer significant (

p > 0.1), while the regression coefficients of other variables were still significant (

p < 0.001). In summary: (1) Perceived usefulness played a partial mediating role among economic benefit, convenience and participation intention, supporting hypotheses H2b and H3b. (2) Enjoyment played a partial mediating role among sustainability, trust and participation intention, supporting hypotheses H5b and H7b. (3) Enjoyment played a full mediating role between sense of belonging and participation intention, supporting hypothesis H6b.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The growing collaborative consumption is now bringing huge changes to consumer purchasing and consumption, and will affect their lives in the future. However, collaborative consumption enterprises need to know more about motivation affecting consumer participation to help them to survive, and sustainable development of collaborative consumption needs to capture the real needs of users. In an effort to better understand collaborative consumption, this study developed and tested an original model for explaining consumer outcomes in this new environment based on an extension of the theory of self-determination.

The motivation for participating in collaborative consumption for users are both intrinsic and extrinsic, and extrinsic motivation is a more prominent factor than internal motivation. However, from the perspective of long-term development, with the upgrading of consumption structure, intrinsic motivation cannot be neglected. In extrinsic motivation, the regression weight associated with convenience was larger than economic benefit. This result indicates that, as the living standard rises, economic benefit is no longer the primary factor for users to consider; they pay more attention to the improvement of living efficiency brought by convenience. In intrinsic motivation, trust was the most important factor, which shows that the insecurity and uncertainty caused by the asymmetry of information and the imperfection of the system in collaborative consumption will greatly affect users’ intention. The regression weight of sense of belonging and sustainability had no big difference. Users feel part of the community in collaborative consumption, adding to a feeling of enjoyment and intention to participate. Users realize that participating in collaborative consumption is an activity that protects the environment and saves resources, thereby increasing inner satisfaction and participation intention.

The model in this study not only makes a significant contribution to the emergent stream of literature on the sharing economy, but also enriches the theory of self-determination. This study found that factors related to collaborative consumption or perceived usefulness and enjoyment did not affect intention alone. In fact, perceived usefulness and enjoyment as mediating variables, and variables related to collaborative consumption were key antecedents of them. Particularly, enjoyment played a full mediation between sense of belonging and participation intention. This study contributes by discovering the important role of perceived usefulness between instrumental/functional value (i.e., economic benefit and convenience) and participation intention, and the important role of enjoyment between psychological needs (i.e., sustainability, sense of belonging and trust) and intention. The final research model not only provides a comprehensive coverage of extrinsic and intrinsic factors to understand consumer self-determination behavior, but also explores the internal mechanism of motivation in a collaborative consumption context.

This research has implications for practice of collaborative consumption stakeholders.

From the perspective of extrinsic motivations, economic benefit and convenience should be considered to improve consumers’ perceived usefulness and intention to participate. Enterprises can increase consumers’ economic benefit through discount and free strategy, thereby enhancing their usage habits and “stickiness”. However, enterprises also need to consider the negative effects of single economic stimulus, relying solely on low-price strategies does not have the momentum for sustainable development. In terms of convenience, enterprises should increase innovation in product function design, make it simpler, and let users get feedback as soon as possible. In the product launch, scientific planning and layout should be made so that resources and users can match quickly and accurately, saving users time and effort.

From the perspective of intrinsic motivations, psychological needs on trust, sense of belonging and sustainability should be focused to enhance consumers’ enjoyment and intention. In terms of trust, enterprises should transfer positive information through social media to establish a good reputation; they can also establish special complaints and suggestions channels and provide timely feedback so that users can have ways to compensate for the loss of profits to reduce the user’s inner insecurity. Meanwhile, enterprises should establish a comprehensive mechanism to protect the privacy of consumers. From sustainability, products or services should be closely linked to the theme of “green” and “environmental protection” and root it in the heart of users, so that they feel that using the products or services is conserving resources and contributing to the ecological environment, thereby creating a pleasant experience. For example, some shared bicycle companies organized various activities with other Internet green public welfare departments to stimulate users to form a conditional reflection between bicycle sharing and environmental protection. For the sense of belonging, enterprises should be committed to building communities to satisfy users’ social relationship needs. Sabitzer et al. [

35] found communities should reduce conflicts through soft regulation to promoting sustainability in sharing economy. Community managers can encourage community members to cooperate with each other through physical rewards, virtual points, level promotion, etc., or interact with community users online or offline, so that users can feel that they are members of a product or service community, thereby increasing pleasure and intention to participate. For instance, DiDi, a car-sharing company, organizes offline communication activities “Di Di Park” from time to time and provide gifts to users.

This study has limitations that point to the directions of future research. First, collaborative consumption has various types, and bicycle sharing is just one of them; other collaborative consumption types should be used to test the model in the future. Second, there is a lack of diversity in the sample; because young people with higher education are more open to collaborative consumption, a new concept, and they are the main users of its products and services, they are the majority in the survey. It is expected that more middle-age consumers will join collaborative consumption and future studies may include them in the samples to test the model and compare the results. Third, conducting the research in a certain environment and country is a limitation. Different contexts could affect different motivations and alter the results. The geographic scope of this work is limited to one country, and future research should aim to collect more observations from other countries involved in collaborative consumption and test the research model.