How One Rural Community in Transition Overcame Its Island Status: The Case of Heckenbeck, Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Theoretical Considerations

3.1. Sustainability Transitions

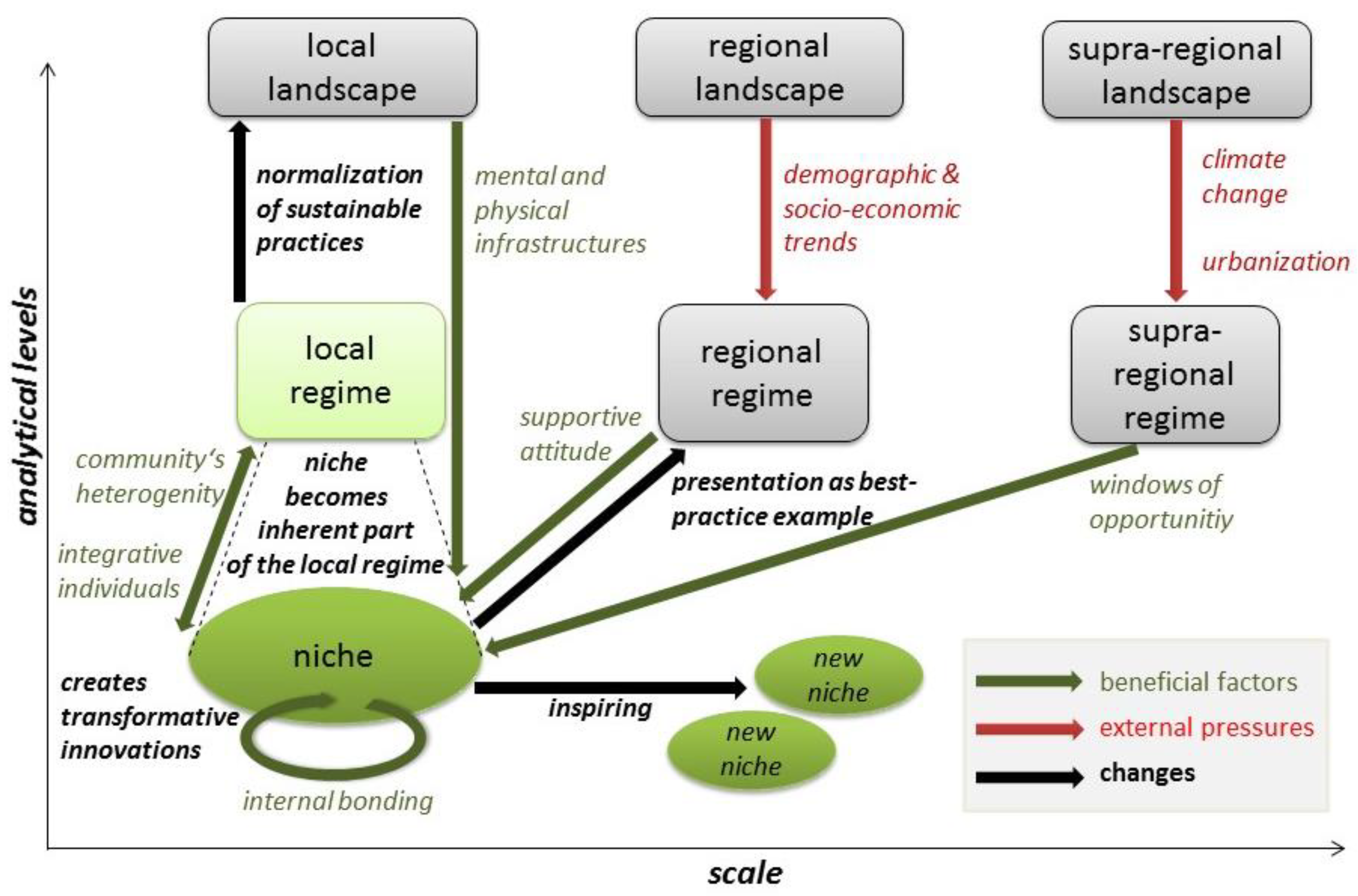

3.2. The Multi-Level Perspective

- (1)

- Niches are different kinds of protected spaces, in which radical novelties are conceptualized that altogether challenge the present regime. In classical socio-technical transition theory, these niches are seen primarily in corporate research and development laboratories or in state-run demonstration projects. The niche actors are mostly entrepreneurs or scientists, who hope for their promising novelties to be eventually used in the regime or even replace it [30]. Yet, Lawhon & Murphy [37] convincingly criticized this narrow focus, which only accounts for a subset of actors who shape transitions. They speak up for also including consumers, workers, and activists into the framework in order to prevent the concept from getting trapped in techno-economic determinisms, and to enable developing pluralistic and participatory institutions for transition governance. Against this backdrop, we take CiTs as niches. By doing so, we extend the framework by another group of actors who shape transition and who have been left unacknowledged in socio-technological theory so far.

- (2)

- Regimes constitute the more pervasive and stable level of MLP, which is based on alignments of existing technologies and infrastructure, established institutions and networks, as well as routinized practices and cultural discourses [40]. In existing regimes, innovation is mostly incremental, as they are highly stabilized by path dependencies and by lock-in mechanisms of economic (sunk investments in competence, factories, and infrastructure), social (cognitive routines, social networks, user practices, lifestyles) and political kind (active opposition to change from groups with vested interests). While niches struggle against these well-entrenched socio-technical regimes, Shove [44] argues that this struggle cannot be limited to technical artefacts that may or may not prevail in the market. She demonstrates that artefacts do not necessarily arise to meet existing demands, since social needs themselves are created. This said, in this study we do not restrict our gaze on artefacts, which would lead to a rather apolitical lens on socio-technical transitions, but focus primarily on the shaping and reshaping of social practices that precede the development of specific social or technical solutions [44].

- (3)

- The landscape is the wider context that surrounds both the niches as well as the regimes. It comprises material aspects such as the geomorphic structure or climate of a region, slowly changing societal aspects such as demographics, political ideologies, or macroeconomic trends, but also sudden events of translocal impact such as oil price fluctuations, recessions, wars or major technical incidents like the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima [43]. All these factors can be combined in a single category, since as a whole they form the external context that cannot be influenced in the short term by niche or regime actors [37,40].

- (1)

- Experimentation: In the first phase, radical innovations emerge in niches, often outside or at the margins of the existing regime. Social networks of innovative actors are fragile in this phase, since there are no stable rules of interaction, various design options for artefacts and institutions, and overall much uncertainty. It is the phase of experimentation and testing [40].

- (2)

- Emerging trajectories: In the second phase, innovations break out of their protected niches to slowly establish a foothold in society. Learning processes of innovators stabilize into dominant patterns and the innovation develops a trajectory of its own.

- (3)

- Competition: In the third phase, the innovation diffuses into mainstream society where it competes with existing technology and the wider socio-technical regime. This phase is often characterized by struggles on multiple dimensions: Economically, there is market competition between new and existing technologies. On the business dimension, there are struggles between new entrants and incumbents. Politically, there are power struggles about the precise settings of policy instruments. Discursively, there are struggles about cultural interpretations, which frame problems and solutions in certain ways [40].

- (4)

- Regime change: The fourth phase, eventually, is characterized by the transition itself, which occurs “when there is a disruption in the system that results in a new ‘architecture’ or system structure” [37] (p. 357). Noteworthy, transitions usually take time to complete, often decades or more. They become anchored in institutions and new agencies, practices, mind-sets, professional standards, and technical capabilities. While they might provide solutions to some of the non-sustainable assemblages, they also create new unintended consequences that need to be monitored and potential losers might need to be compensated [40].

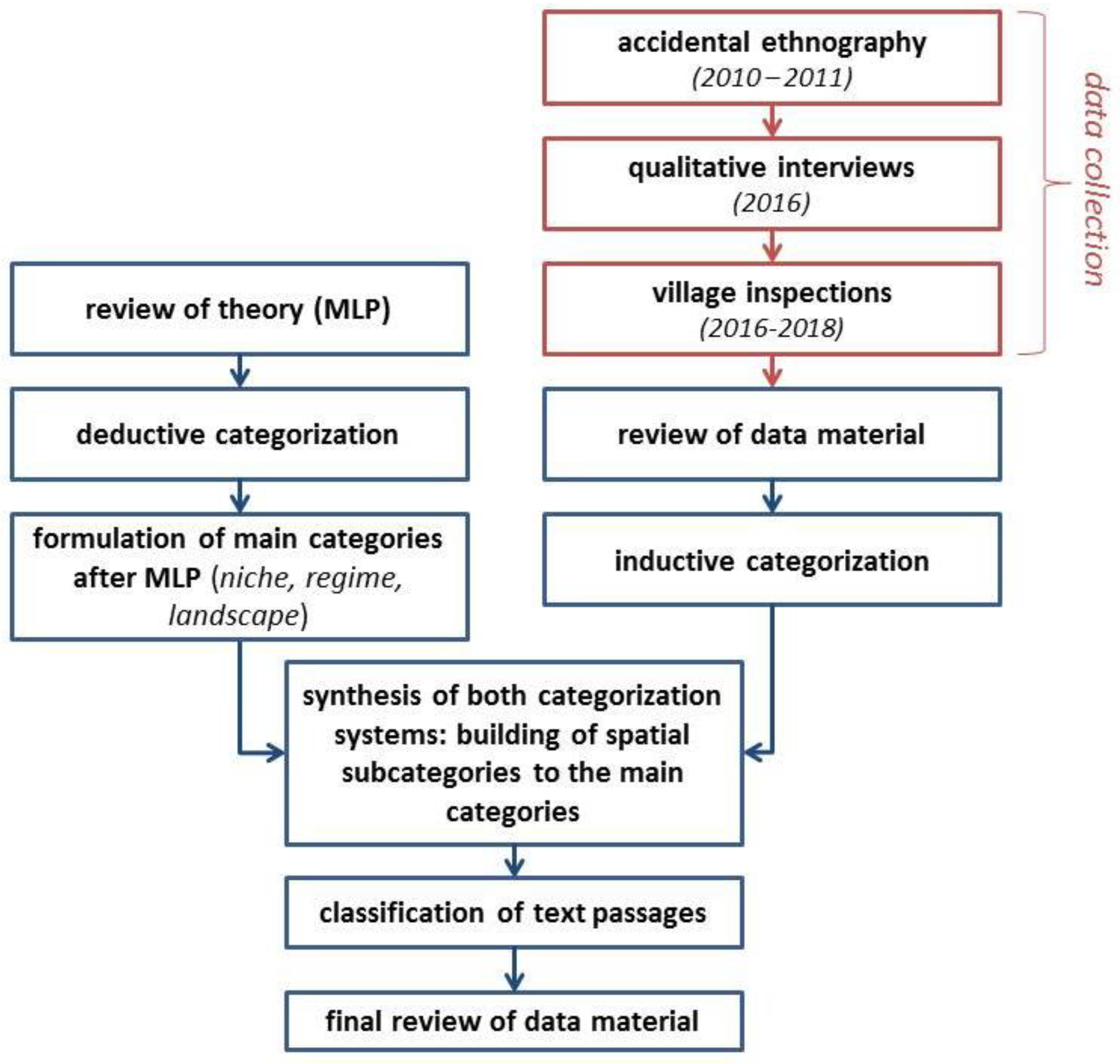

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Heckenbeck as CiT

5.2. Experimentation and Emerging Trajectories in Heckenbeck

5.2.1. The Socio-Technical Niche

5.2.2. Socio-Technical Regime

“There was a perspective like: ‘They [the newcomers] are a little mad […]. It’s all a bit strange and unfamiliar, […] they [the locals] had a personal distance to those people [the newcomers] at first, how they looked like, how they behaved and they rejected that […]. At first it was a relatively heavy divide”.(IP 2)

5.2.3. Socio-Technical Landscape

“[Heckenbeck’s overall development] proved against this [skeptical] attitude […], because it was unmistakable that this village generated so much energy, which also flowed into the region. And if people from southern Germany move to Heckenbeck to send their children to the [local] school […] then of course this has a charm and it can’t be rejected”.(IP 2)

5.3. Competition and Regime Change in Heckenbeck

5.3.1. Dynamics in the Socio-Technical Niche

“That is, I think, the reason, why this is in a way so successful, because I do not perceive this compulsion to participate here and there or to champion a specific ideology. Therefore, it is a much more varied blend and also much less threatening”.(IP 3)

5.3.2. Niche, Regime and Landscape Interplay at the Local Level

“This is the clue from my perspective that it was quite simple for the newcomers here. Especially in our table tennis and football teams we always enjoyed a large clientele from the district. That’s why it wasn’t so difficult for the newcomers to arrive on the scene here […]. Because it wasn’t unusual, when suddenly a stranger appeared, whom no one knew”.(IP 7)

5.3.3. Niche, Regime and Landscape Interplay at the Regional Level

5.3.4. Niche, Regime and Landscape Interplay at the Supra-Regional Level

“The assessment team finally did not recognize what was a newcomers’ project and what was a project of the locals. We showed them everything together […]. We passed the gun club house [dt.: Schützenhaus], then we came to the local organic shop and then to the vegetable field of the community-supported agriculture”.(IP 7)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A strong social self-isolation of niche actors from the surrounding regime might create protective frames to provide spaces for experimentation. However, in the long run, these innovations will remain within their niches and fail to spread into mainstream society, if no relations to regime actors exist [10]. The chances for spreading increase the more the alternative lifestyles are practiced visibly and openly. An accessible alternative infrastructure as part of the established village structures helps to overcome barriers for participating in niche projects.

- (2)

- In contrast to technological innovations, the diffusion of sustainable practices and sufficiency-oriented lifestyles is a much more protracted process. Social practices and lifestyles embedded in structural non-sustainability are fixed by means of physical and mental infrastructures, which are difficult to change [1,30]. Our case shows that the bridging of distant milieus—in our case of ‘newcomers’ and ‘locals’—can successfully take place when face-to-face interactions happen on a regular basis. In Heckenbeck, the joint creation of a village identity and of social cohesion was highly successful. Furthermore, the important role of spaces for sustainability transitions became clear. Innovative practices lead to new physical infrastructure, which has in turn effects on the practices of others. In this way, the ideas of a CSA or the free school became experienceable by people outside the niche, who integrated them into their daily routines. On the basis of daily encounter, new lifestyles were thus taken up not (only) due to moral reasons, but (also) due to their mere practicability. As Smith et al. [43] (p. 444) phrase it, “places bring meaningful historical and social narratives into the realization of abstract goals. They generate regionally relevant visions whose symbolism and specificity carry greater moral authority as a result.”

- (3)

- Even on a local level, regime transitions are conflictual and generate resistance. This resistance can be overcome by intense efforts to organize events that enable encounters and successively create a mutual understanding between niche and regime actors. For fostering sustainable innovations in administrations, communicative and courageous actors, strategic networks and partnerships, media attention and/or scientific reputation can help. Yet, without specific windows of opportunity offered by the regime and landscape, niche innovations are at risk of failing by not spreading into mainstream society. Thus, the identification and utilization of windows of opportunity by niche actors play a crucial role and often are decisive of either success or failure. In the light of our findings, we confirm the statement of Smith et al. [43] (p. 441) that “both strong socio-technical alternatives and favorable openings in the regime selection environments” are essential factors for transitions to succeed.

- (4)

- These favorable openings do not occur by chance or automatisms but are mostly results of political decisions. The MLP enriches the transition research by the focus on the structural framework and its interplay with transformative niche actors. Against this backdrop, it is necessary to address politics and planning authorities to create structural framework conditions that facilitate civic transition processes by providing accessible windows of opportunity and dismantling obstacles for its realization on a local scale. The solution of urgent sustainability challenges must not be unilaterally shifted to individuals in a neoliberal logic, but is a central task of politics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schürmann, K. Die Stadt als Community of Practice: Potentiale der nachhaltigkeitsorientierten Transformation von Alltagspraktiken. Das Beispiel Seattle; Transformationen; oekom: München, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-86581-481-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Transition Research Network (STRN). A Research Agenda for the Sustainability Transition Research Network. Available online: https://transitionsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/STRN_Research_Agenda_2017.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2018).

- German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). Humanity on the Move: Unlocking the Transformative Power of Cities: Flagship Report; Wissenschaftlicher Beirat d; Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen: Berlin, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-936191-45-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kühnel, K. Von Verlusten, Peak Oil und Raumpionieren. Lokale Anpassungs- und Widerstandsstrategien in ländlichen Räumen. In Transformation der Gesellschaft für Eine Resiliente Stadt- und Regionalentwicklung: Ansatzpunkte und Handlungsperspektiven für die Regionale Arena; Hahne, U., Ed.; Rohn: Detmold, Germany, 2014; pp. 173–188. ISBN 978-3-939486-86-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, I. Soziale Innovationen für Eine Zukunftsfähige Lebensweise: Gemeinschaften und Ökodörfer als Experimentierende Lernfelder für Sozial-Ökologische Nachhaltigkeit; Ecotransfer: Münster, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-939019-07-7. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Karvonen, A. Living Laboratories for Sustainability. Exploring the Politics and Epistemology of Urban Transition. In Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Bulkeley, H., Castan Broto, V., Hodson, M., Marvin, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 125–141. ISBN 978-0-415-58697-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hahne, U.; Kühnel, K. Regionale Resilienz und postfossile Raumstrukturen. Zur Transformation schrumpfender Regionen. In Transformation der Gesellschaft für eine Resiliente Stadt- und Regionalentwicklung: Ansatzpunkte und Handlungsperspektiven für die Regionale Arena; Rohn: Detmold, Germany, 2014; pp. 11–32. ISBN 978-3-939486-86-2. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M.; Miskowiec, J. Of Other Spaces. Diacritics 1986, 16, 22–27. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/464648?origin=crossref (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Grewer, J. Transformationsraum Heckenbeck? Ein Dorf als Pionier des Wandels. In Transformationsräume: Lokale Initiativen des Sozial-Ökologischen Wandels; Keck, M., Faust, H., Fink, M., Gaedtke, M., Reeh, T., Eds.; ZELT-Forum; Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2017; pp. 33–58. ISBN 978-3-86395-343-0. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, M. Vom Neuen Guten Leben: Ethnographie Eines Ökodorfes; Kultur und soziale Praxis; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-8376-2828-9. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, M. Must Utopia Be an Island? Positioning an Ecovillage Within Its Region. Soc. Sci. Dir. 2013, 2, 9–18. Available online: http://www.socialsciencesdirectory.com/index.php/socscidir/article/view/98 (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). World in Transition: A Social Contract for Sustainability; German Advisory Council on Global Change: Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-936191-37-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stadt Bad Gandersheim Integriertes Städtebauliches Entwicklungskonzept (ISEK). 2016. Available online: https://www.bad-gandersheim.de/portal/seiten/integriertes-staedtebauliches-entwicklungskonzept-isek--900000013-23910.html (accessed on 18 October 2018).

- Landkreis Northeim Regionales Entwicklungskonzept (REK) Harzweserland zur Teilnahme am ILE- und LEADER-Auswahlverfahren für die Förderperiode 2014–2020 in Niedersachsen. Handeln für den Wandel. 2015. Available online: http://www.harzweserland.de/wp-content/uploads/REK-Harzweserland_WebVers.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2018).

- Klüver, D. Pampaparadiese. Soziokultur in ländlichen Räumen. In Soziale Arbeit in ländlichen Räumen; Debiel, S., Engel, A., Hermann-Stietz, I., Litges, G., Penke, S., Wagner, L., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 315–326. ISBN 978-3-531-17936-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kielhorn, M. Wenn die Menschen Interessiert Und Tolerant Sind, Entsteht Vieles Von Allein. LandInForm 2011, 4, 30. Available online: https://www.netzwerk-laendlicher-raum.de/fileadmin/sites/ELER/Dateien/05_Service/Publikationen/LandInForm/2011/Integration_LiF_11_4_Wolf.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2018).

- Schröder, M. Lebensqualität im ländlichen Raum. Heckenbeck als Erfolgsmodell zukunftsfähiger Dorfentwicklung? 2014. Available online: http://www.alr-hochschulpreis.de/2014_Wettbewerbsbeitrag_Marit_Schroeder.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Hildebrandt, S. Die Mischung Macht’s. Land Forst 2013, 69, 60–61. Available online: http://www.heckenbeck-online.de/heckenbeck/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Land_und_Forst_Juni_2013.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Fertmann, M.; Wachhaus, S.; Pietscher, C.; Keunecke, F. Lust auf Dorf. NDR—Die Nord. 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVij5WVymE4 (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Wehmeyer, A. Die Mischung macht’s. LandInForm 2011, 4, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hollbach-Grömig, B.; Langel, N.; Wagner, A. Demographischer Wandel—Herausforderungen und Handlungsempfehlungen für Umwelt- und Naturschutz. Teil II: Aufstockung des F+E-Vorhabens; Umweltbundesamt (UBA): Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2013; pp. 53–55. Available online: edoc.difu.de/edoc.php?id=KPRJ4OXF (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Polzin, R. Ein Dorf, das wächst. In Chance Demographischer Wandel vor Ort; Deutsche Vernetzungsstelle Ländliche Räume, Ed.; Bundesanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Ernährung: Bonn, Germany, 2012; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-9169-143-2. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-0-87663-165-2. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford Paperbacks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-19-282080-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/461472a (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorman, A.H. Societal Metabolism. In Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era; D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., Kallis, G., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015; pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-1-138-00076-6. [Google Scholar]

- Keck, M.; Faust, H.; Fink, M.; Gaedtke, M.; Reeh, T. Transformationsräume: Lokale Initiativen des Sozial-Ökologischen Wandels; ZELT-Forum; Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-86395-343-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Schot, J.; Hoogma, R. Regime Shifts to Sustainability Through Processes of Niche Formation: The Approach of Strategic Niche Management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1998, 10, 175–198. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09537329808524310 (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Sommer, B.; Welzer, H. Transformationsdesign: Wege in eine Zukunftsfähige Moderne; Transformationen; oekom: München, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-86581-845-4. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J.W. From persistent problems to system innovations and transitions. In Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge Studies in Sustainability Transitions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-415-87675-9. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U.; Wissen, M. Social-Ecological Transformation. In International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology; Richardson, D., Castree, N., Goodchild, M.F., Kobayashi, A., Liu, W., Marston, R.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-470-65963-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U. Sozial-ökologische Transformation. In Wörterbuch Klimadebatte; Bauriedl, S., Ed.; Edition Kulturwissenschaft; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2016; pp. 277–283. ISBN 978-3-8376-3238-5. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Disruption and Low-Carbon System Transformation: Progress and New Challenges in Socio-Technical Transitions Research and the Multi-Level Perspective. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 224–231. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214629617303377 (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Roach, B. Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-138-65947-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hussen, A.M. Principles of Environmental Economics and Sustainability: An Integrated Economic and Ecological Approach, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-415-67690-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lawhon, M.; Murphy, J.T. Socio-Technical Regimes and Sustainability Transitions: Insights From Political Ecology. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 354–378. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0309132511427960 (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Peet, R.; Robbins, P.; Watts, M. Global Political Ecology; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-415-54814-4. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-Technical Systems. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0048733304000496 (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability. In Perspectives on Transitions to Sustainability; European Environment Agency, Ed.; EEA Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; pp. 45–69. ISBN 978-92-9213-939-1. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. The dynamics of transitions. A socio-technical perspective. In Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge Studies in Sustainability Transitions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 11–104. ISBN 978-0-415-87675-9. [Google Scholar]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability Transitions: An Emerging Field of Research and Its Prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S004873331200056X (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Voß, J.-P.; Grin, J. Innovation Studies and Sustainability Transitions: The Allure of the Multi-Level Perspective and Its Challenges. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 435–448. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0048733310000375 (accessed on 18 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Sustainability, System Innovation and the Laundry. In System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability: Theory, Evidence and Policy; Elzen, B., Geels, F.W., Green, K., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northhampton, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 76–94. ISBN 978-1-84376-683-4. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, L.; Benneworth, P.; Truffer, B. Toward a Spatial Perspective on Sustainability Transitions. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 968–979. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0048733312000571 (accessed on 19 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Fujii, L.A. Five Stories of Accidental Ethnography: Turning Unplanned Moments in the Field Into Data. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 525–539. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1468794114548945 (accessed on 19 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. Scaled geographies: Nature, place and the politics of scale. In Scale and Geographic Inquiry: Nature, Society, and Method; Sheppard, E.S., McMaster, R.B., Eds.; Blackwell Pub: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 129–153. ISBN 978-0-631-23069-4. [Google Scholar]

- Welzer, H. Mental Infrastructures How Growth Entered the World and Our Souls; Heinrich Böll Foundation: Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-86928-060-8. [Google Scholar]

- Petzold, T.D. Bis die Kreativität explodierte. Anfang und Wachsen einer Gemeinschaft. KursKontakte 2006, 144, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Global Ecovillage Network (GEN). Auftaktveranstaltung. In Proceedings of the Conference Leben in zukunftsfähigen Dörfern (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (BMUB); Umweltbundesamt (UBA)), Bad Gandersheim/Heckenbeck, Germany, 9–11 June 2017; Available online: https://gen-deutschland.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/9.-11.06.2017_BildProtokoll_Auftaktveranstaltung_Heckenbeck.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2018).

- Klüter, H. Wettbewerbe und Rankings der Gebietskörperschaften. Regionale Entwicklung als Ergebnis eines Spiels? In Städte und Regionen im Standortwettbewerb: Neue Tendenzen, Auswirkungen und Folgerungen für die Politik; Kauffmann, A., Rosenfeld, M.T.W., Eds.; Forschungs- und Sitzungsberichte der ARL; ARL; Akad. für Raumforschung und Landesplanung: Hannover, Germany, 2012; pp. 49–70. ISBN 978-3-88838-067-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, D.; Antpöhler, J.; Bergengruen, K.; Emanuel, R.; Frenzel, H.-G.; Günther, J.; Kielhorn, M.; Petzold, T.D.; Stenz, I.; Wiese-Günther, G. Unser Dorf hat Zukunft—Bewerbung; Heckenbeck, 2012; Available online: http://www.heckenbeck-online.de/heckenbeck/wpcontent/uploads/2012/04/Unser_Dorf_hat_Zukunft.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2018).

| Interview Partner (IP) | Role | Social Group | Sex | Profession |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP 1 | Teenager who grew up in Heckenbeck | Newcomer | Female | Student |

| IP 2 | Employee in Heckenbeck and inhabitant of the neighboring town Bad Gandersheim | External | Male | Biologist and teacher |

| IP 3 | Inhabitant and employee in Heckenbeck | Newcomer | Male | Headmaster of the local school |

| IP 4 | Inhabitant and first village leader of the newcomers’ group from 2011–2015 | Newcomer | Female | Former village leader |

| IP 5 | Administrative head of the building authority and deputy mayor of the borough Bad Gandersheim | External | Male | Administrative staff |

| IP 6 | Regional Manager of the district Northeim who provides support for regional village development and moderation including Heckenbeck | External | Female | Administrative staff |

| IP 7 | Inhabitant of Heckenbeck; actively involved in many local associations; editor for local newspaper | Local | Male | Press officer of the borough Bad Gandersheim |

| IP 8 | Inhabitant of Heckenbeck | Newcomer | Female | Gardener in the local community supported agriculture |

| Niche | Regime | Landscape | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local level |

|

|

|

| Regional level |

|

|

|

| Supra-regional level |

|

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grewer, J.; Keck, M. How One Rural Community in Transition Overcame Its Island Status: The Case of Heckenbeck, Germany. Sustainability 2019, 11, 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030587

Grewer J, Keck M. How One Rural Community in Transition Overcame Its Island Status: The Case of Heckenbeck, Germany. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030587

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrewer, Janes, and Markus Keck. 2019. "How One Rural Community in Transition Overcame Its Island Status: The Case of Heckenbeck, Germany" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030587

APA StyleGrewer, J., & Keck, M. (2019). How One Rural Community in Transition Overcame Its Island Status: The Case of Heckenbeck, Germany. Sustainability, 11(3), 587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030587