Work Volition and Career Adaptability as Predictors of Employability: Examining a Moderated Mediating Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Employability

2.2. Career Adaptability

2.3. Work Volition

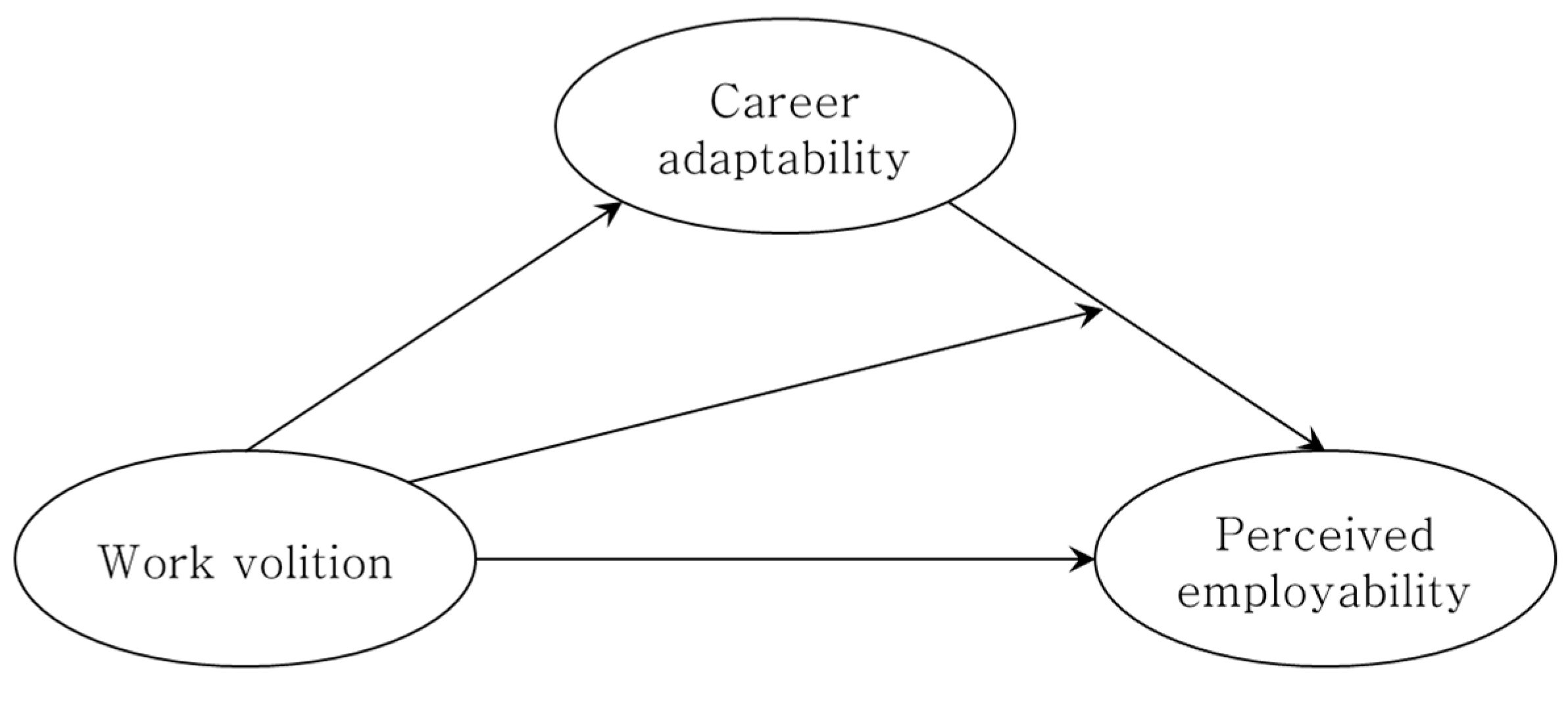

2.4. Research Model and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings and Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atitsogbe, K.A.; Mama, N.P.; Sovet, L.; Pari, P.; Rossier, J. Perceived employability and entrepreneurial intentions across university students and job seekers in togo: The effect of career adaptability and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tymon, A.; Harrison, C.; Batistic, S. Sustainable graduate employability: An evaluation of ‘brand me’ presentations as a method for developing self-confidence. Stud. High. Educ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedeman, D.V.; O’Hara, R.P. Career Development: Choice and Adjustment; College Entrance Examination Board: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.T. A theoretical model of career subidentity development in organizational settings. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1971, 6, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Guan, Y.; Wu, J.; Han, L.; Zhu, F.; Fu, X.; Yu, J. The interplay of proactive personality and internship quality in chinese university graduates’ job search success: The role of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 109, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnano, P.; Santisi, G.; Zammitti, A.; Zarbo, R.; Di Nuovo, S. Self-perceived employability and meaningful work: The mediating role of courage on quality of life. Sustainability 2019, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstrøm, V.H.; Drange, I.; Mamelund, S.E. Employability as an alternative to job security. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, R.; Fazi, L.; Guglielmi, D.; Mariani, M.G. Enhancing substainability: Psychological capital, perceived employability, and job insecurity in different work contract conditions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologa, R.; Lupu, A.-R.; Boja, C.; Georgescu, T.M. Sustaining employability: A process for introducing cloud computing, big data, social networks, mobile programming and cybersecurity into academic curricula. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokker, R.; Akkermans, J.; Tims, M.; Jansen, P.; Khapova, S. Building a sustainable start: The role of career competencies, career success, and career shocks in young professionals’ employability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Gorgievski, M.J.; De Lange, A.H. Learning at the workplace and sustainable employability: A multi-source model moderated by age. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelzet, E.; Picco, E.; Houkes, I.; Bosma, H.; de Rijk, A. Effectiveness of interventions to promote sustainable employability: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J.; Ashforth, B.E. Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillage, J.; Pollard, E. Employability: Developing a Framework for Policy Analysis; Department for Education and Employment: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; de Lange, A.H.; Demerouti, E.; Van der Heijde, C.M. Age effects on the employability–career success relationship. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Diemer, M.A.; Perry, J.C.; Laurenzi, C.; Torrey, C.L. The construction and initial validation of the work volition scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.R.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.H. Social support and occupational engagement among korean undergraduates: The moderating and mediating effect of work volition. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L. Career adaptability and academic satisfaction: Examining work volition and self efficacy as mediators. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadidian, A.; Duffy, R.D. Work volition, career decision self-efficacy, and academic satisfaction: An examination of mediators and moderators. J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Autin, K.L.; Bott, E.M. Work volition and job satisfaction: Examining the role of work meaning and person-environment fit. Career Dev. Q. 2015, 63, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukgoze-Kavas, A.; Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P. Exploring links between career adaptability, work volition, and well-being among turkish students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The theory and practice of career construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Lent, R.W., Brown, S.D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L. Career construction theory and practice. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 2nd ed.; Lent, R.W., Brown, S.D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bocciardi, F.; Caputo, A.; Fregonese, C.; Langher, V.; Sartori, R. Career adaptability as a strategic competence for career development: An exploratory study of its key predictors. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.S.; Luciano, E.C.; Maggiori, C.; Ruch, W.; Rossier, J. Validation of the german version of the career adapt-abilities scale and its relation to orientations to happiness and work stress. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, A.B.; Choi, K.O. The relations of employability skills to career adaptability among technical school students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H. Career adaptability predicts subjective career success above and beyond personality traits and core self-evaluations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 84, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; Sel, L. The concept employability: A complex mosaic. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2003, 3, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versloot, A.; Glaudé, M.; Thijssen, J. Employability: A Multiform Labour Market Phenomenon; MGK: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid, R.; Lindsay, C. The concept of employability. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesser, D.L. The employability skills initiative in colorado. J. Career Dev. 1984, 11, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaerman, R.; Spill, R. A dialogue on employability skills: How can they be taught? J. Career Dev. 1988, 15, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Dodd, L.J.; Steele, C.; Randall, R. A systematic review of current understandings of employability. J. Educ. Work 2016, 29, 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinares Insa, L.I.; Zacarés González, J.J.; Córdoba Iñesta, A.I. Discussing employability: Current perspectives and key elements from a bioecological model. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.G. Career Development Learning and Employability; Higher Education Academy: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, A.; Arnold, J. Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhercke, D.; De Cuyper, N.; Peeters, E.; De Witte, H. Defining perceived employability: A psychological approach. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, S.; Fiori, M.; Thalmayer, A.G.; Rossier, J. Investigating the link between trait emotional intelligence, career indecision, and self-perceived employability: The role of career adaptability. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hootegem, A.; De Witte, H.; De Cuyper, N.; Elst, T.V. Job insecurity and the willingness to undertake training: The moderating role of perceived employability. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yizhong, X.; Lin, Z.; Baranchenko, Y.; Lau, C.K.; Yukhanaev, A.; Lu, H. Employability and job search behavior: A six-wave longitudinal study of chinese university graduates. Empl. Relat. 2017, 39, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.S. A systematic review of the career adaptability literature and future outlook. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E.; Knasel, E.G. Career development in adulthood: Some theoretical problems and a possible solution. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1981, 9, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundson, N.E.; Harris-Bowlsbey, J.E.; Niles, S.G. Essential Elements of Career Counseling: Processes and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Neureiter, M.; Traut-Mattausch, E. Two sides of the career resources coin: Career adaptability resources and the impostor phenomenon. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.K.; Brotheridge, C.M. Does supporting employees’ career adaptability lead to commitment turnover, or both? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.E.; da Silva, J.T.; Paixão, M.P. Career adaptability, employability, and career resilience in managing transitions. In Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience; Maree, K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Arad, S.; Donovan, M.A.; Plamondon, K.E. Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, N.A. Work and vocational psychology: Theory, research, and applications. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. The Psychology of Working: A New Perspective for Career Development, Counseling, and Public Policy; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, L.S. Circumscription and compromise: A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. J. Couns. Psychol. 1981, 28, 545–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L. The role of work in psychological health and well-being: A conceptual, historical, and public policy perspective. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R.D.; Blustein, D.L.; Diemer, M.A.; Autin, K.L. The psychology of working theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, F.; Ngo, H.Y.; Leung, A. Predicting work volition among undergraduate students in the united states and hong kong. J. Career Dev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdonati, J.; Schreiber, M.; Marcionetti, J.; Rossier, J. Decent work in switzerland: Context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, L.M.; Nauta, M.M. College students’ health and short-term career outcomes: Examining work volition as a mediator. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Douglass, R.P.; Autin, K.L.; Allan, B.A. Examining predictors of work volition among undergraduate students. J. Career Assess. 2016, 24, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Bott, E.M.; Torrey, C.L.; Webster, G.W. Work volition as a critical moderator in the prediction of job satisfaction. J. Career Assess. 2013, 21, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Autin, K.L.; Duffy, R.D. Examining social class and work meaning within the psychology of working framework. J. Career Assess. 2014, 22, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autin, K.L.; Douglass, R.P.; Duffy, R.D.; England, J.W.; Allan, B.A. Subjective social status, work volition, and career adaptability: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chomeya, R. Quality of psychology test between likert scale 5 and 6 points. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 399–403. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J. Career adapt-abilities scale—korea form: Psychometric properties and construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Coxe, S.; Baraldi, A.N. Guidelines for the investigation of mediating variables in business research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.O.; Neyman, J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat. Res. Mem. 1936, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.52 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| 2. University1 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.05 | |||||||

| 3. University2 | 0.48 | 0.46 | −0.03 | −0.05 | ||||||

| 4. College1 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | |||||

| 5. College2 | 0.28 | 0.45 | −0.09 | −0.31 | −0.27 | −0.29 | ||||

| 6. College3 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.20 | −0.02 | 0.19 | −0.06 | |||

| 7. Work volition | 4.87 | 1.04 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.37 | −0.31 | 0.16 | ||

| 8. Career adaptability | 4.52 | 1.26 | −0.02 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.18 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.26 | |

| 9. Perceived employability | 4.38 | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.20 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.49 |

| Career Adaptability a | Perceived Employability b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| University1 | 0.14 * | 0.12 * | 0.15 * | 0.12 * | 0.10 |

| University2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| College1 | 0.15 * | 0.11 | 0.15 * | 0.13 * | 0.09 |

| College2 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.13 * | −0.12 * | −0.11 |

| College3 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Work volition | 0.24 * | 0.29 * | 0.23 * | ||

| Career adaptability | 0.42 ** | 0.38 ** | |||

| Work volition × Career adaptability | 0.22 * | ||||

| R-squared | 0.063 * | 0.113 ** | 0.091 * | 0.374 ** | 0.401 ** |

| △R-squared | 0.050 * | 0.283 ** | 0.027 * | ||

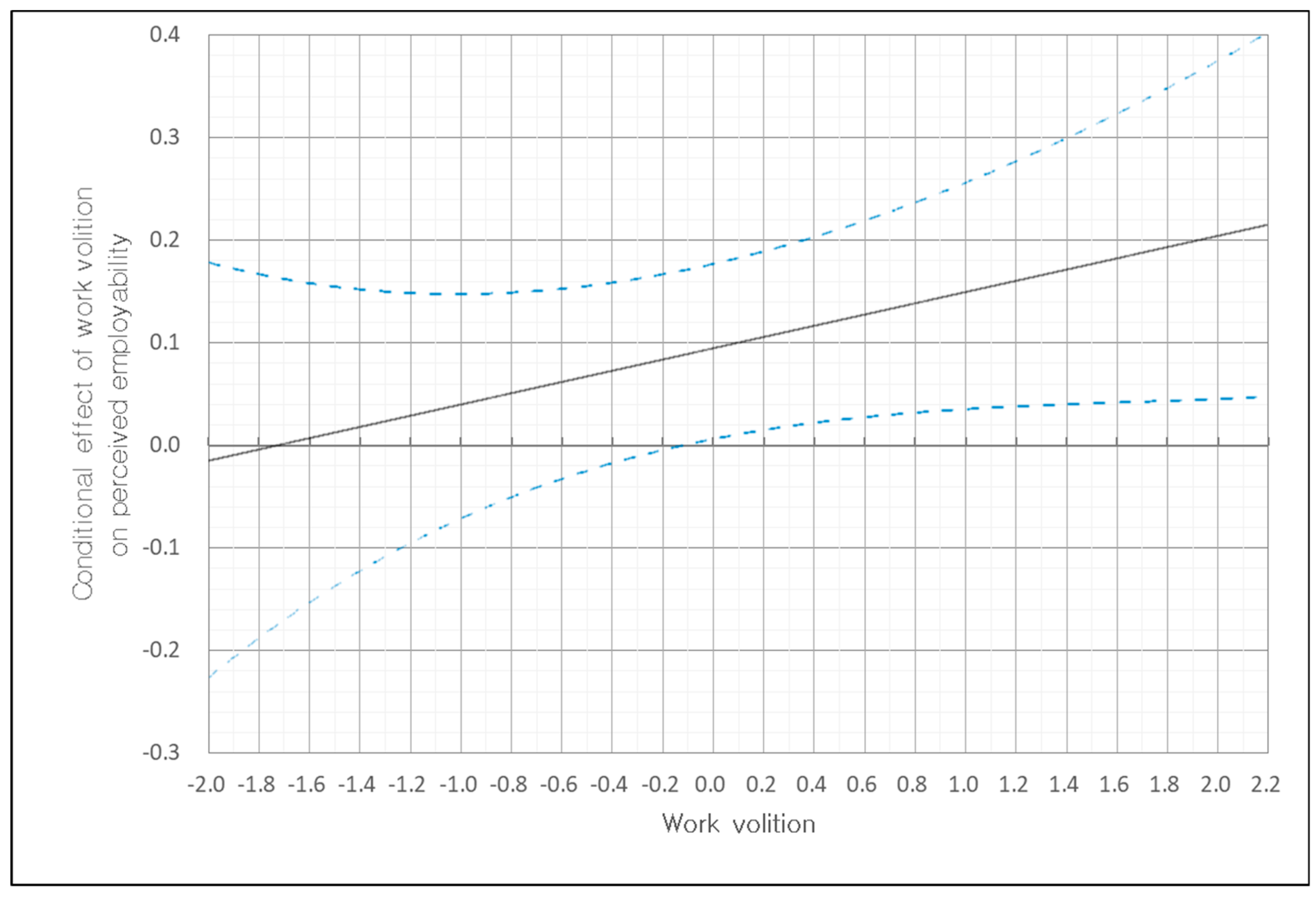

| B | SE | LLCI a | ULCI b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Conditional indirect effect | ||||

| Work volition(+1SD) | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.28 |

| Work volition(mean) | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Work volition(−1SD) | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.15 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, J.E. Work Volition and Career Adaptability as Predictors of Employability: Examining a Moderated Mediating Process. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247089

Kwon JE. Work Volition and Career Adaptability as Predictors of Employability: Examining a Moderated Mediating Process. Sustainability. 2019; 11(24):7089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247089

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Jung Eon. 2019. "Work Volition and Career Adaptability as Predictors of Employability: Examining a Moderated Mediating Process" Sustainability 11, no. 24: 7089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247089

APA StyleKwon, J. E. (2019). Work Volition and Career Adaptability as Predictors of Employability: Examining a Moderated Mediating Process. Sustainability, 11(24), 7089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247089