1. Introduction

A nation’s higher-education institutions are a repository of skills, talents, innovation and expertise that drive its economy and its social well-being. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive global-development project launched in September 2013, with the expectation that it has enormous potential to offer greater opportunities not limited to those of one country or of one region or of the business community, is also attracting international students to its universities, projecting the country as an increasingly coveted destination for them, and, as Wen and Hu [

4] stated, an emerging regional hub for higher education. Today, more than 60 percent of its more than 492,000 international students are from BRI countries [

5]. Those developments have been in the works since 1978, when China opened its doors to the international community, primarily for business partnerships. Since then, its political influence has also grown and its educational system transformed, making it an increasingly popular choice destination for international students. In light of the growing interest of international students in China’s higher-education institutions and the reaffirmation of China’s commitment to expanding educational opportunities for “Silk Road” countries through scholarship programs [

1,

6,

7,

8,

9], it is imperative, that China sustain the modernization of its educational system and explore strategies for strengthening its instructional capacity [

10]. It is against that backdrop that this article develops, within the BRI context, an integrated, conceptual framework for enhancing (classroom) instructional communication between international students and their Chinese faculty. Such a focus departs from the common research emphasis on the teacher’s communication skills in the classroom and on her or his competence as the sender of the message [

11,

12]. But, more important, the present study examines international students’ classroom experiences, a palpably missing dimension in instructional communication research in which “college students constitute the group of greatest interest to instructional communication scholars” [

13] (pp. 461–462).

Cast against the preceding background, then, the purpose of this article is two-fold. First, it examines classroom misunderstandings strictly as an artifact of interculturality or intercultural constraints [

14] and develops a framework that can be used to better respond to international students’ classroom concerns, thereby sustaining and enhancing the impact of BRI, specifically through higher education, as the second of the three epigraphs enunciates. The framework presented here is based on the results of previous studies; however, admittedly, it is yet to be confirmed empirically. It focuses and places the onus of understanding on the students’ communicative competence—that is, listening to and making meanings of their instructional faculty’s oral proficiency in the language of instruction, say, Mandarin Chinese. This article subscribes to the views of De Jager and Evans [

11] that even though misunderstandings can occur from a teacher’s utterances being insufficiently clear, the learner is conventionally obligated to listen and to pay attention to the speaker. Therefore, this article is not concerned about speech acts used by Chinese teachers to accomplish their communicative goals; rather, it focuses on “misunderstanding [as] ... exclusively related to the hearer” [

15] (p. 768). Similarly, as Nelson, Carson, Batal, and El Bakary [

16] noted, misunderstandings occur when a hearer perceives the message differently from that intended by the speaker. Thus, any pragmatic failure in understanding—that is, misunderstanding—is attributed to the hearer [

16].

Second, it presents an erumpent approach to sustaining BRI by enhancing instructional communication, an approach that departs from the dominant theoretical anchors in the General Theory of Instructional Communication [

17,

18,

19]. It focuses on the students’ lived experiences in a culturally disparate environment, even as it iterates the mission of BRI as a strategic, integrated undertaking geared toward both maritime and educational development of institutional charges—international students.

There are at least three reasons for our focus on higher-education institutions. First, to enhance the instructional capacity of China’s universities and colleges. China’s Ministry of Education statistics for 2018 indicate that there were 492,185 international students from 196 countries or areas studying in 1004 higher-education institutions in China’s 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and provincial-level municipalities [

20]. Nearly 60 percent came from Asia, 17 percent from Africa, 15 percent from Europe, and about 8 percent from the United States. International students’ communicative competence in a host country’s dominant language or in its communication styles is a sine qua non for their effective cross-cultural adaptation to and their success in their new milieu [

21,

22]. Absent of such competence, misunderstandings and communication mismatches tend to occur for a variety of reasons: the inaccurate expressions used by a sojourner in conversations with a native speaker, the mammoth difficulties and conflicts a student has in recognizing words and in ascribing meanings to and in interpreting them in a classroom, the pragmatic failure that results from a mismatch or discrepancy between a speaker’s expressions and a hearer’s unintentional misinterpretation, and an undeveloped communicative competence in a language in which nonnative speakers of the language of communication misunderstand a speech act or struggle with expressing themselves [

11,

12,

14,

15,

23,

24]. “Misunderstanding,” writes Weigand [

15], “is a form of understanding which is partially or totally deviant from what the speaker intended to communicate” (p. 769). Such misunderstandings can lead to negative judgments or stereotyping [

25], particularly on the part of the instructor.

Second, to provide an erumpent platform that reduces international students’ instructional misunderstandings that may result from their inadequate oral proficiency in the language of instruction (or learning) and lead to their failure to accomplish their educational goals, goals consistent with the spirit of BRI. Their pent-up frustration with the teacher–student interaction could result in their negative perceptions of the overall educational experience, threatening a major segment of BRI. Granted, misunderstandings occur in all encounters, including those among native speakers of the same language [

14]. For international students in China’s universities, however, the mismatch between their professors’ speech acts and the students’ interpretation of those acts is exacerbated by the students’ limited oral proficiency in the dominant language of instruction.

Third, to present a synergy between BRI and China’s higher education—an intersection not lost on China’s Ministry of Education. As Lavakare [

26] put it, China can “ensure economic development through higher education” (p. 13). Particularly noteworthy are that “the skills and talents cultivated by private universities can be adjusted to match emerging industries, and management can be changed according to policy trends” [

27] (p. 401). Thus “China’s private [and public] universities can help usher in new opportunities for social and economic development (p. 401), trajectories to which BRI is tethered.

The rest of this article is organized into five sections—that is, 2 to 6. In

Section 2, we note that our conceptual framework acknowledges the multicultural orientations of international students whose healthful experiences will contribute to sustaining BRI. In

Section 3 and

Section 4, we present a two-pronged theoretical perspective that underpins our conceptual framework. In

Section 5, we specify the three key constructs in our framework and conclude in

Section 6 with an answer to the question, What’s next for the innovative intersection of China’s higher education and BRI? We answer that question by presenting five implications of our framework for sustaining BRI.

2. Instructional Communication: Cultural Underpinnings and Classroom Challenges

Because this article emphasizes the cultural characteristics of international students as major antecedent variables in instructional communication in China’s university classrooms, it adopts a modified framework that combines key elements of two instructional communication models and two intercultural sensitivity models. The point here is that the conceptual framework will emphasize the multicultural orientations of international students as they communicate in an instructional setting, enabling and sustaining a major initiative that may have contributed in the first place to their presence in China. Higher education, more so in its international realm, is a hallmark of the growing significance of BRI; in other words, as assessment of its impact on the well-being of its participants requires a concomitant assessment of the experiences of international students from BRI countries.

As noted in an introductory paragraph in

Section 1, China’s universities and colleges are increasingly of interest to international students. Complementing that interest is the phenomenal sustained growth in the country’s global influence—politically, militarily and economically—resulting in its commensurate attraction to international students seeking higher education. That influx, partly a consequence of higher education as a state-directed effort under the Belt and Road Initiative, enhances China’s political and economic agendas globally, strengthens mutual understanding among Asian countries, and promotes the significance of the Chinese language in global economic and educational markets [

28].

In 1950, China received its first group of 33 international students, all of whom came from a handful of East European countries. In 2010, it launched its “Study in China Program” to make it even more competitive in the international student market [

28]. This interest in internationalizing China’s higher education is noted by Bentao [

29], who wrote, “The international mobility of university students is the most dynamic aspect of internationalization and a basic approach of Chinese research universities as they build world-class universities” (p. 88).

Such an increasing interest in international education is underscored by this article’s epigraphs, which suggest that education in the international realm reaps healthful tangible benefits for the People’s Republic. And international students continue heading to China for higher education. However, as Yu and Downing [

30] noted, “Despite these developments, this particular group of students remains one of the most under studied international student populations” (p. 458).

Even though some studies [

31,

32,

33,

34] have addressed the importance of international students’ acculturation in and adaptation to China and to its universities, instructional communication—that is, communication for the purpose of engaging students academically and reducing problematic understanding significantly—is a bane of the educational experience of international students in China. As Wang and Lin [

35] noted, “a good knowledge of Chinese learning culture and mutual communication are significant factors for both teachers and students” (p. 195). Moreover, Peng and Wu [

36] also suggested that host communication competence and host social communication are two significant pathways to international students’ cross-cultural adaptation.

As Chiang [

37] noted, “Given that intercultural communicators do not possess the same stock of linguistic and cultural knowledge, problematic understanding is bound to occur” (p. 463). For example, Western students usually do not like their Chinese professors’ public reporting of student grades, their professors’ in-class criticisms of students who fail to answer questions correctly and their professors’ tendency to compare publicly student grades or learning outcomes [

33]. Most of the studies on international students enrolled in higher-education institutions analyzed English-medium instruction [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44] rather than focusing specifically on instructional communication in cross-cultural settings in China’s universities. He and Chiang [

39] highlighted three key issues: (a) English-medium programs in China’s higher-education institutions tend to have teachers and international students who are nonnative-English speakers, (b) international students tend to perceive their Chinese teachers’ instructional communication a challenge because of their unusual accent and their sometimes minuscule English-language proficiency, and (c) Chinese teachers’ instructional communication style is more culture-bound. Again, these studies are only limited to instruction in English-medium programs, while the present study applies an approach that integrates intercultural sensitivity models to provide a framework of instructional communication in an attempt to enhance international students’ academic experience and to reduce their misunderstandings. Therefore, the present study will

also help international students enrolled in Chinese-medium programs that are mostly offered through the China Scholarship Council.

Thus, it is critical to address instructional communication within the context of cultural differences. The conceptual framework presented here offers pointers toward addressing the challenges of instructional communication, thereby enhancing it between the growing number of international students in China and their Chinese faculty. Even though misunderstandings in instructional communication can reside in the teacher or professor as the message sender who uses inaccurate expression or inadequate speech acts that may result in misunderstandings [

11], this article focuses

not on the professor as the sender of classroom information but on the international student as the receiver of that information. Strictly within the instructional communication context in the Chinese educational environment, this article attempts to fill that gap in the scholarly literature.

We shall now turn our attention to a two-pronged theoretical framework that is the foundation of our integrated, conceptual insights into how the international student experience in China’s universities can be enhanced. The theories are deemed appropriate primarily because of their heuristic attributes—that is, their capacity to provide conceptual resources for organizing and explaining our knowledge about the international student in China’s multicultural classroom, to serve as guideposts in providing proper contexts for international students’ instructional challenges in the classroom, and to focus future research on the pivotal relevance of their experience to sustaining China’s landmark development agenda that is revamping the world order.

4. Theoretical Framework II: Intercultural Sensitivity Models

A number of sensitivity models have been developed to predict and explain the experiences of sojourners in a new cultural environment and their orientations toward cultural differences. From an intercultural communication perspective, the conceptual framework proposed in this article also draws upon two intercultural communication models, Chen and Starosta’s [

46,

47] intercultural communication competence model and Bennett’s [

48,

49] Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity, both of which are arguably the most investigated in the intercultural communication field. Both fill a gap in the need to better manage the challenges and limitations of—and to enhance—instructional communication between a growing number of Wuhan-area international students and their Chinese instructional faculty. And they also have national implications for China’s growing efforts to better structure learning and teaching in its higher-education institutions.

4.1. Chen and Starosta’s Intercultural Communication Competence Model

Chen and Starosta [

47] developed, in the U.S. context, the intercultural communication competence (ICC) model, which integrates features of both the cross-cultural attitude and the behavioral skills models and which has been tested in a variety of cultural settings. According to the authors, ICC comprised three dimensions: (a) intercultural awareness (cognitive), which refers to the person’s ability to understand similarities and differences of others’ cultures; (b) intercultural sensitivity (affective), which refers to the emotional desire of a person to acknowledge, appreciate, accept and embrace cultural differences; and (c) intercultural adroitness (behavioral), which refers to an individual’s ability to reach communication goals while interacting with people from other cultures. On the basis of this overarching conceptual direction, Chen and Starosta [

50] expounded on the nature and components of intercultural sensitivity and developed a measuring instrument, the intercultural sensitivity scale (ISS), by which they distinguished between intercultural sensitivity and intercultural communication competence, pointing out that the ICC includes cognitive, affective, and behavioral ability of interacting individuals in the process of intercultural communication while IS is an independent concept consisting of six variables: self-esteem, self-monitoring, open-mindedness, empathy, interaction involvement, and nonjudgment.

Self-esteem is an individual’s sense of self-worth and self-respect. Individuals with high levels of self-esteem are better able to cope with psychological and emotional difficulties in the process of intercultural communication in a host society. They believe that they can manage their interactions in a host culture and will be accepted by others. In other words, individuals with self-esteem have positive attitudes and respect toward intercultural differences, which can lead to effective interpersonal relationships with host members.

Self-monitoring, a construct of intercultural sensitivity, is the ability to identify situational constraints in order to adjust and change one’s behaviors to result in competence in communication. Individuals with high self-monitoring can monitor their social behaviors and self-representation in a better way in a diverse cultural atmosphere, and are more observant, sensitive, other-oriented and adaptable in intercultural communication [

51,

52].

Chen and Starosta [

46] defined open-mindedness as “the willingness of individuals to openly and appropriately explain themselves and to accept other’s explanations” (p. 8). They further explained that open-minded individuals are more eager to “recognize, accept, and appreciate different views and ideas” (p. 9), and, thus, have a more diverse and broadened worldview and are more actively involved in the process of intercultural communication.

Empathy, also labeled intuition or telepathic sensitivity, is a vital element of intercultural sensitivity [

47,

48,

53]. It refers to an individual’s ability to enter into a “culturally different counterparts’ mind to develop the same thoughts and emotions in interaction” [

50] (p. 5). It enables individuals to be more sensitive to other people’s internal thoughts and emotions, more open to others’ reactions and understanding in an intercultural communication situation [

54,

55]. In other words, empathy is a strong indicator of one’s level of intercultural sensitivity.

Interaction involvement represents “a person’s sensitivity ability in interaction” [

46] (p.10). It consists of three important concepts associated with the ability to be interculturally sensitive: responsiveness, perceptiveness, and attentiveness [

56,

57]. An interculturally sensitive person has the ability to sustain an effective flow of communication by engaging in a culturally proper way during intercultural interactions and by receiving and giving culturally appropriate messages in such settings.

Nonjudgment reflects the quality of a sensitive person by “allowing oneself to sincerely listen to one’s culturally different counterparts, instead of jumping to conclusion without sufficient information” [

50] (p. 5). Being nonjudgmental can engender interaction and establish relationships with people from diverse cultural backgrounds, and, as an element of intercultural sensitivity, pave the way to a fulfilling intercultural communication experience. This analysis points to the overarching relevance—and the complexity—of the cultural landscape on which the international student navigates. That proess is further enabled—and fostered—by an intercultural development process to which we now turn.

4.2. Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity

The Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) is a six-stage process of intercultural learning. It is a journey from resistance to openness and from ethnocentrism to ethnorelativism. It assumes a linear development—that is, having a beginning, an intermediate point, an end. However, it is important to note that, regarding sojourners, the model also considers the possibility of “retreat” or “regress” in the process of cross-cultural adaptation.

The first three stages of the model—denial, defense, minimization—are conceptualized as ethnocentric, by which one’s own culture is experienced as a center of reality. In the denial stage, one’s own culture is experienced as the only real one, which could be because of isolation or wholly deliberate separation from other cultures. In the defense stage, one’s own culture is experienced as the only good one, thus categorizing experiences into “us and them” and generating a concept of “we”-superior and “they”-inferior in cultural perspectives. The last stage of ethnocentrism is minimization in which elements of one’s own cultural worldviews are experienced as universal and differences are accepted only at face value.

In ethnorelative stages—acceptance, adaptation, integration—a resident’s own culture is experienced within the context of other cultures. These stages represent a journey of the individual from an unknown cultural difference to a known or from the unfamiliar to the cultural difference.

In the acceptance stage, one’s own culture is experienced as one of complex worldviews. People at this stage are curious to know about the cultural differences and have respect for other cultures, yet cultural differences do not mean “agreement” and may be judged negatively. At the adaptation stage, one’s own worldview is expanded to include constructs from other worldviews and people are able to look at the world with “different eyes”, thus changing their behavior to accommodate effectively new and different cultures. This shift of mindset is not an artificial one, but one based on cognitive, affective and behavioral skills of adjustments to a new cultural environment.

The last stage of the Bennett model is integration, in which one’s experiences of oneself have become so multicultural that she or he can move into and out of other cultures freely and comfortably. Individuals often confront matters associated with their own “cultural marginality”, which Bennett further classified into two: encapsulated and constructive cultural marginality. Encapsulated refers to one’s separation from culture and experiences alienation, while constructive acknowledges cultural differences and becomes a necessary part of one’s identity and thus a person becomes bicultural, transcending cultural boundaries while maintaining her or his cultural identity.

Ethnorelative orientations are a way to acknowledge cultural differences, either by accepting their significance by adapting to or incorporating cultural differences into one’s own personality. Thus, development of intercultural sensitivity is a shift from a narrow, self-centered worldview to an open, mature one that emerges by engaging oneself in meaningful relationships with members of diverse cultures.

5. An Instructional Communication Framework for China’s University Classrooms

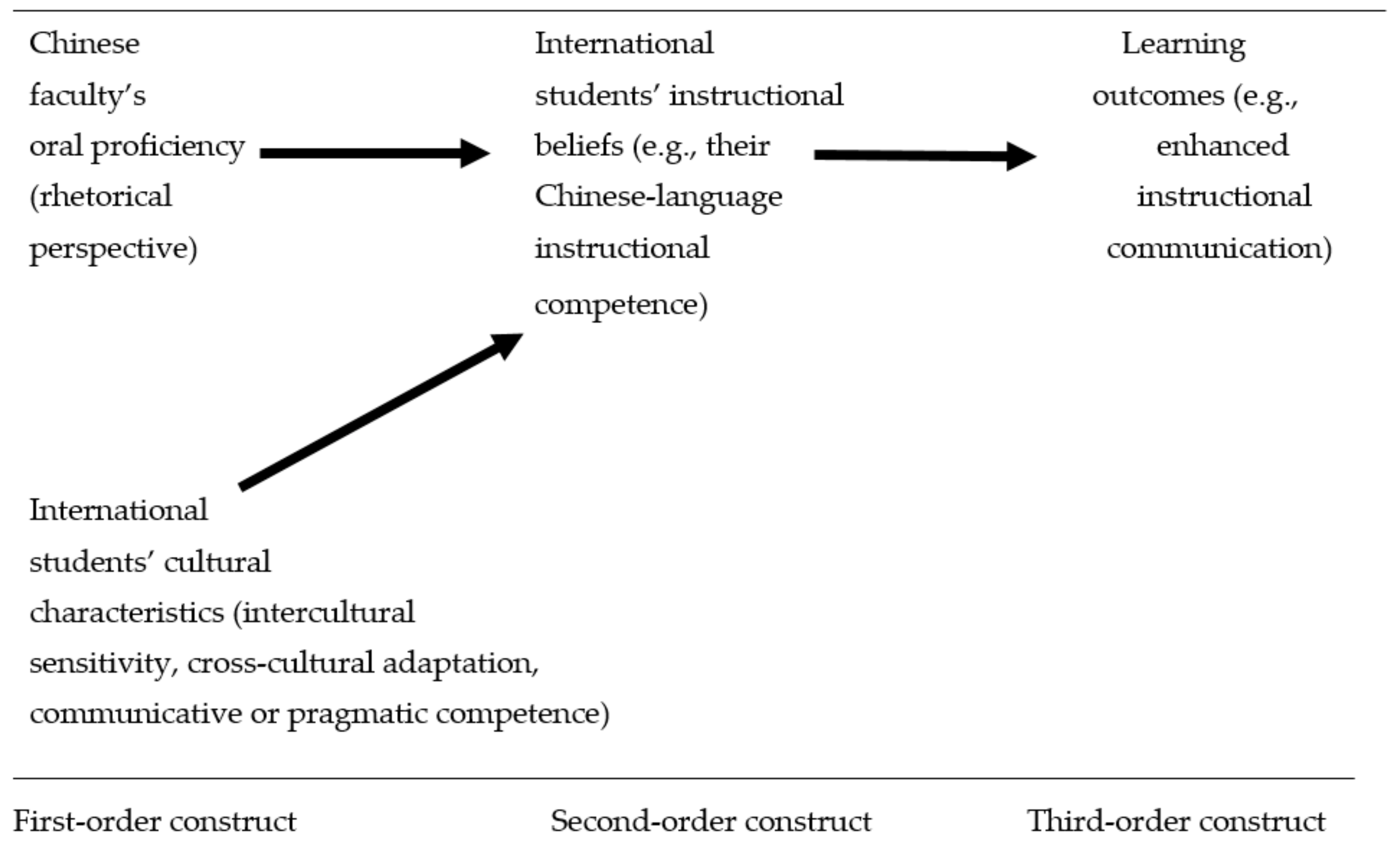

This article focuses on misunderstandings in intercultural settings in which international students’ difficulties with the dominant language of instruction could lead to negative learning outcomes. As both instructional models indicate, several variables determine the students’ learning outcomes; however, because of the focus of this article is on students’ perceptions of the oral proficiency of their professors vis-à-vis the students’ language limitations, the conceptual framework for enhancing instructional communication in the classroom is a linear relationship among three variables: Chinese professor’s oral proficiency as perceived by the international students whose instructional beliefs (e.g., the students’ instructional ability in Chinese-language) influence learning outcomes (

Figure 1). In classrooms, the relationship becomes all too apparent. Why? Because such settings can engender limited understandings that emanate from, among other factors, what Thomas [

58] labelled “cross-cultural pragmatic failure” to describe exclusively misunderstandings that arise from the hearer’s “inability to understand ‘what is meant by what is said’” (p. 91). And she uses “pragmatic competence” to describe the hearer’s “ability to use language effectively in order to achieve a specific purpose and to understand language in context” (p. 92).

Two approaches to the study of instructional communication dominate the research literature: the relational and the rhetorical [

17,

24]. In the relational approach, teachers and students exchange information and share understandings mutually. In the rhetorical approach, which is consistent with China’s high-context, implicit-communication style, instructional communication is a teacher-controlled process that views the teacher as the primary source of information (in additional to selected readings) and students as receivers and learners.

The framework presented in this article has two first-order variables: oral proficiency and student characteristics, both of which influence students’ instructional beliefs about their professors’ communication proficiency. Student characteristics include the five elements outlined in Byram’s [

59] model of intercultural communicative competence:

attitudes (savoir être), that is, one’s openness and readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and belief about one’s own;

knowledge (savoirs), that is, one’s interactions with individuals and with society;

skills of interpreting and relating (savoir comprendre), that is, one’s ability to interpret an event from another culture and relate it to one’s own;

skills of discovery or interaction (savoir apprendre or faire), that is, one’s ability to acquire new knowledge of another culture; and

critical cultural awareness or political education (savoir s’engager), that is, one’s ability to evaluate critically practices and outcomes in one’s own culture, as well as in others’.

In other words, students arrive in China with various levels of intercultural competencies and “different orientations or predispositions that influence their approach to and performance in the instructional setting” [

45].

Studies on intercultural sensitivity and cultural adaptation of international students indicate that intercultural sensitivity (e.g., language proficiency) has a positive effect on the sociocultural adaptation of international students [

30,

31,

60]. Thus, this article integrates the theories of intercultural sensitivity and of the six-stage cross-cultural adaptation to develop a framework that explains the importance of instructional beliefs of international students on university campuses in China. Additionally, it should be noted that, within the context of the two intercultural sensitivity models, this is the first comprehensive framework on the sociocultural and academic experiences of international students in China vis-à-vis instructional communication in the classroom.

The importance of students’ cultural characteristics as a first-order variable was established by Akhtar and Pratt [

61], who reported that intercultural sensitivity had a significant positive effect on sociocultural adaptation, but a weak effect on academic adaptation. Bringing that strand of research to bear on this proposed conceptual framework means that for international students to overcome academic barriers, a new perspective on sensitivity needs to be adopted and their competencies in the host language assessed. That study described that sensitivity as academic intercultural sensitivity in the Chinese context, which can help to enhance the level of academic adaptation of international students in China. The rationale behind that view is that general intercultural sensitivity only helps in sociocultural adaptation, but seldom offers a solution to the challenges of academic adaptation.

Second, Akhtar and Pratt [

61] reported that sociocultural adaptation had a weak impact on academic adaptation while academic adaptation had a strong impact on sociocultural adaptation, which meant, on the one hand, that if international students were satisfied with their academic environment, they could adjust with relative ease to the sociocultural environment. If, on the other hand, they were satisfied with their sociocultural environment but were not satisfied with their academic environment, their overall adaptation to China could be undermined. Furthermore, the students’ satisfaction with sociocultural adaptation and with their academic adaptation could enable them to adapt better to a new society. Failure in either case could negatively affect their adaptation to China.

Unlike in Western higher-education institutions, where most international students already have language skills to immerse themselves in the mainstream academic environment, a majority of international students in China’s universities arrive without any academic language competency and understanding of China’s educational system. Consequently, this lack of academic intercultural sensitivity creates significant problems for international students as they seek to adapt academically in China’s universities. Thus, a rationale for the conceptual framework presented in this article is predicated on the broad range of the importance of students’ cultural characteristics as precursors to their instructional experience. In other words, if the international students’ language competency were minuscule, then instructional barriers would be apparent, undercutting their instructional competence and compromising their overall classroom experience and their adaptation to a new environment: China’s universities.

The second-order construct, instructional beliefs, include the students’ expectations for success, self-efficacy and empowerment [

45], and their Chinese-language instructional competence.

This framework is based on the proposition that a higher proficiency in host-country language will manifest itself in enhanced instructional communication that reduces the likelihood of cross-cultural pragmatic failure and enhances the likelihood of pragmatic competence. It is assumed that those learning outcomes—that is, products of a process—will inform future rhetorical activities of Chinese professors, making instructional communication an action, an interaction, and a transaction: “Instructional communication is the process by which teachers and students stimulate meanings in the minds of each other using verbal and nonverbal messages” [

19] (p. 5). It must be noted here that if (Chinese) instructional faculty are tethered to the rhetorical process in a manner that disregards student needs and motivations, then the likelihood that the students’ communicative competence will be stymied becomes feasible. Earlier studies (e.g., [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]) indicated only English-medium programs’ instructional issues and evaluated their challenges; therefore, our conceptual framework presents a more integrated approach to reducing misunderstandings between Chinese professors and their international students in classrooms. This present study is an effort to provide a more culturally sensitive instructional communication in the Chinese context to better accomplish a knowledge-based economy under BRI.

6. Conclusions and Implications of Framework for Sustaining BRI

What are the implications of instructional communication in China in an intercultural context for an innovative, synergistic sustainability of BRI? This article is the first attempt to conceptualize the key elements in students’ understanding of classroom material within the context of China’s growing multiculturalism in higher education and of its Belt and Road Initiative. Our discussion suggests five major implications of the instructional settings of China’s multicultural classrooms for sustaining and broadening BRI.

First, it is important to acknowledge the asymmetrical discourses or unequal encounters between native and nonnative speakers [

58] in China’s multicultural university classrooms. The implications of such outcomes for learning outcomes need to be better addressed within the context of China’s dominant high-context culture. That calls for using the results of an initial assessment of students’ awareness of speech acts to develop programs that demonstrably acknowledge the conceptual framework proposed here. But perhaps more than those, the administrators of BRI can be more aware of skills and expertise readily available regionally, if not internationally, as they develop projects for the mutual benefit of BRI partners.

Even though a stock-taking of resources for managing long-term projects is being undertaken by various BRI partners with the collaboration of career-development offices on various university campuses and research centers in China, there is a crucial need to develop programs that specifically require, as Cruz [

62] noted, role plays under pragmatic pressure and model dialogues with authentic discourses appropriate in communities of partners. Such participation can place a premium on honing international students’ expertise for BRI support and as an indicant of BRI effect in its own right; on enhancing international students’ communicative competence; and on reducing, if not avoiding, pragmatic failures that emanate from unequal, asymmetrical instructional encounters. As Bennett’s [

48,

49] linear development model states, there will be a progression in such enhancement, even as it is apparent from

Figure 1 that extraneous factors influence the outcome of such a process, ensuring that communication interculturality, which varies from person to person, is not entirely a discretely linear process. Student participants could be provided feedback on their role plays to make them better aware of speech acts and better recognize potential areas of difficulties between their own knowledge and that of a native speaker. But, more important, “students may become aware that their participation in communicative activities may be influenced to some extent by their ... knowledge [of a nonnative language] and sociocultural expectations” [

62] (p. 38).

Second, international students need to be more cognizant of the salient features of Chinese culture (e.g., differences in communication habits and in modes of thinking), the environment, and the educational system

before arriving in China. Inarguably, China’s higher-education system is “highly stratified” [

63] (p. 30): there are the more powerful and the less powerful universities, the leading and the ordinary universities [

64]; the private and the public [

25]; the more than 600 universities of applied technology, which have long been engines for research and development, and are being transformed to focus them on “regional economic development by cooperating with local small and medium enterprises in applied innovation projects” [

63] (p. 30), consistent with BRI mission; the higher-distance-education programs [

65,

66]; and the new, all-research university, the Westlake University, in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. The latter institution, “a cradle of innovative talent in advanced science and technology” [

67] and China’s first private institution approved to award doctoral degrees, emphasizes team-building and team projects that revolve around discovery through advanced basic research and applied, problem-solving, interactive approaches that are not nearly as embraced by other types of China’s universities. Such an institution, can, as Jin [

27] observes in private universities, “help usher in new opportunities for social and economic development” (p. 401), consistent with BRI’s infrastructural goals and with those of its other development programs.

Granted, even though instructional behaviors in China’s university classrooms are not monolithic, they tend to perpetuate characteristics of China’s higher education: hierarchical, authoritarian relationships that tend to cast professors as all-knowing and superior to their students, to favor professor-to-student knowledge transmission and to limit teacher–student classroom interaction [

68,

69,

70,

71]. Such characteristics, therefore, require orientation classes and training workshops offered in and encouraged by China’s embassies and consulates worldwide on how to engage Chinese professors dialogically within much-vaunted cultural practices. Additionally, such embassies can provide videoconferencing and computer-assisted training to help incoming students to better adapt to their new cultural milieu. Because most international students are on financial support provided by the China Scholarship Council, it is also recommended that such a government agency, through China’s embassies and consulates worldwide, become involved in programs such as orientation sessions that better help students to adjust to their new environment. That way, international students’ over-expectations, often based upon misinformation, could be upended, giving way to realistic expectations that would make the students better prepared sociopsychologically for environmental demands and adjustment.

Third, university management of the international student experience [

72] and cultural sensitivity training for faculty members are critical to fostering an academic environment that some students perceive as restrictive culturally. BRI, at bottom, is multiculturalism extraordinaire. Consequently, instructional communication—that is, communication for the purpose of engaging students academically and reducing problematic understanding significantly—a bane of the educational experience of international students in China, must be more forcefully addressed head-on from a policymaking perspective. As Chiang [

37] notes, “Given that intercultural communicators do not possess the same stock of linguistic and cultural knowledge, problematic understanding is bound to occur” (p. 463). And such problems can engender discontent of international with academic programs. For example, Western students, as noted in a preceding section of this article, usually do not like their Chinese professors’ public reporting of student grades, their professors’ in-class criticisms of students who fail to answer professors’ questions, and their professors’ tendency to compare publicly students’ grades or learning outcomes [

35]. Chen and Starosta [

45,

46] aver that intercultural awareness, sensitivity and adroitness will enable interactants to reach their communication goals. Thus, training Chinese professors as a matter of academic expediency in a global context requires that they demonstrate knowledge and skill in nuanced communication with other cultures. For example, nonnative speakers of Mandarin Chinese are always advised to slow down considerably in their English-language presentations to their Chinese hosts. Part of that exhortation is justified in part by the time necessary to have a translator on hand navigate between two disparate languages.

Fourth, universities with substantial international student enrollments should provide on-campus orientations in several languages, including Chinese, English, French and Arabic, to incoming international students. Through such activities, the university staff should be able to answer student inquiries effectively. Students should know more about, say, the registration procedures, the local rules, conventions, practices, the environment and the educational system. Universities can provide profound opportunities for domestic–international student interaction and create a friendly classroom atmosphere for international students. One possibility is having rotating theme classrooms: one month, the theme may be Germany; another, England; and yet another, Egypt. Rotating themes can also be campuswide or schoolwide, providing enormous opportunities for students to connect much more easily with one another, to build friendships, and to foster better understanding and to communicate more in, say, Mandarin Chinese.

Finally, it is imperative that China’s universities have, as a matter of policy, annual university-wide events that showcase their international stature and interest, but strictly within the BRI context. As of today, such events occur, palpably absent BRI themes. Such events—say, “Global Instruction at Wuhan”—will include domestic and international students’ testimonials on personal exchanges on curriculum-related projects, classroom engagements between students and professors, in-class dialogues between international students and their Chinese faculty. Furthermore, partnerships and initiatives will highlight international students’ classroom engagement on a multicultural scale.

It is expected that, absent of empirical evidence, the prescriptions outlined here will require additional government support to participating universities. Such investment is justified by the growing and increasing presence of China on the global stage and by the expanding reach of BRI. The Communist Party of China understands full well that the country has expanded its global influence well beyond the Pacific Rim. As Callahan and Barabantseva [

73] observe, the country’s enhanced global role is being manifested in part in its model of international relations. That model, which informs China’s higher-education policy, intersects with BRI, which, in turn, ensures a pivotal role for China’s international higher education in sustaining and projecting BRI and for the latter in providing a vast network of resoures to the former.