Understanding Attitudes towards Reducing Meat Consumption for Environmental Reasons. A Qualitative Synthesis Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. The Meta-Aggregative Approach

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

3. Results

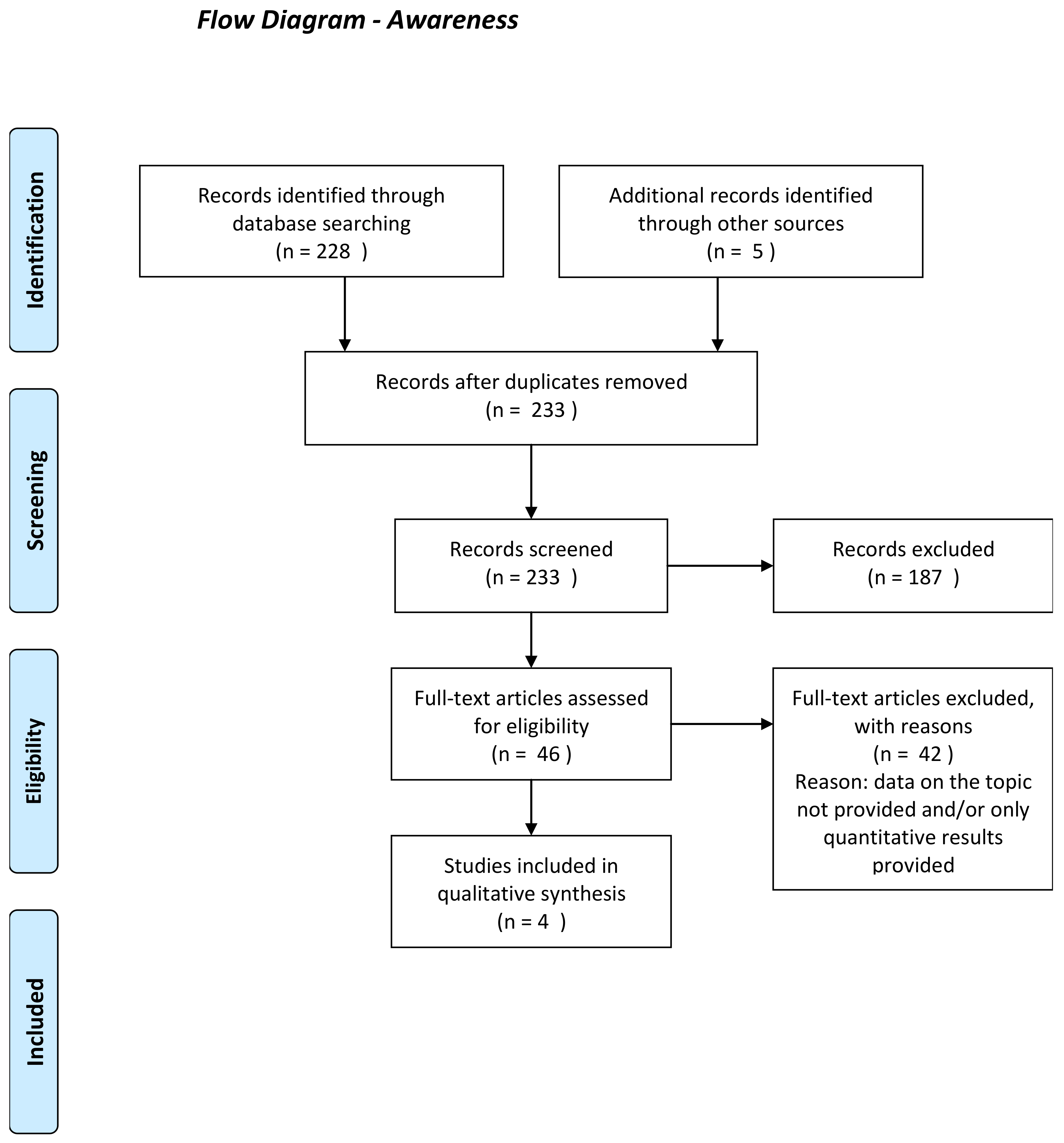

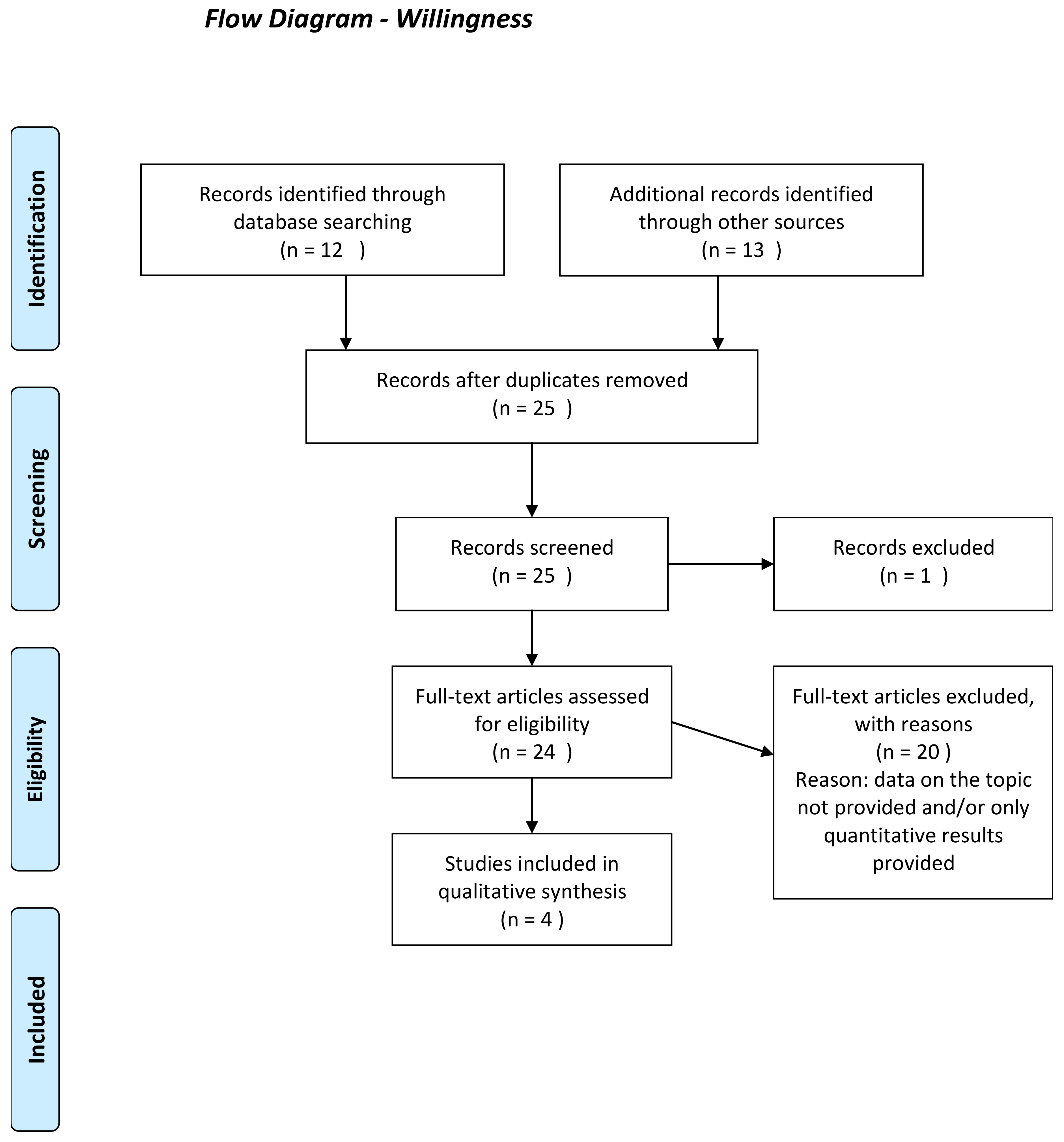

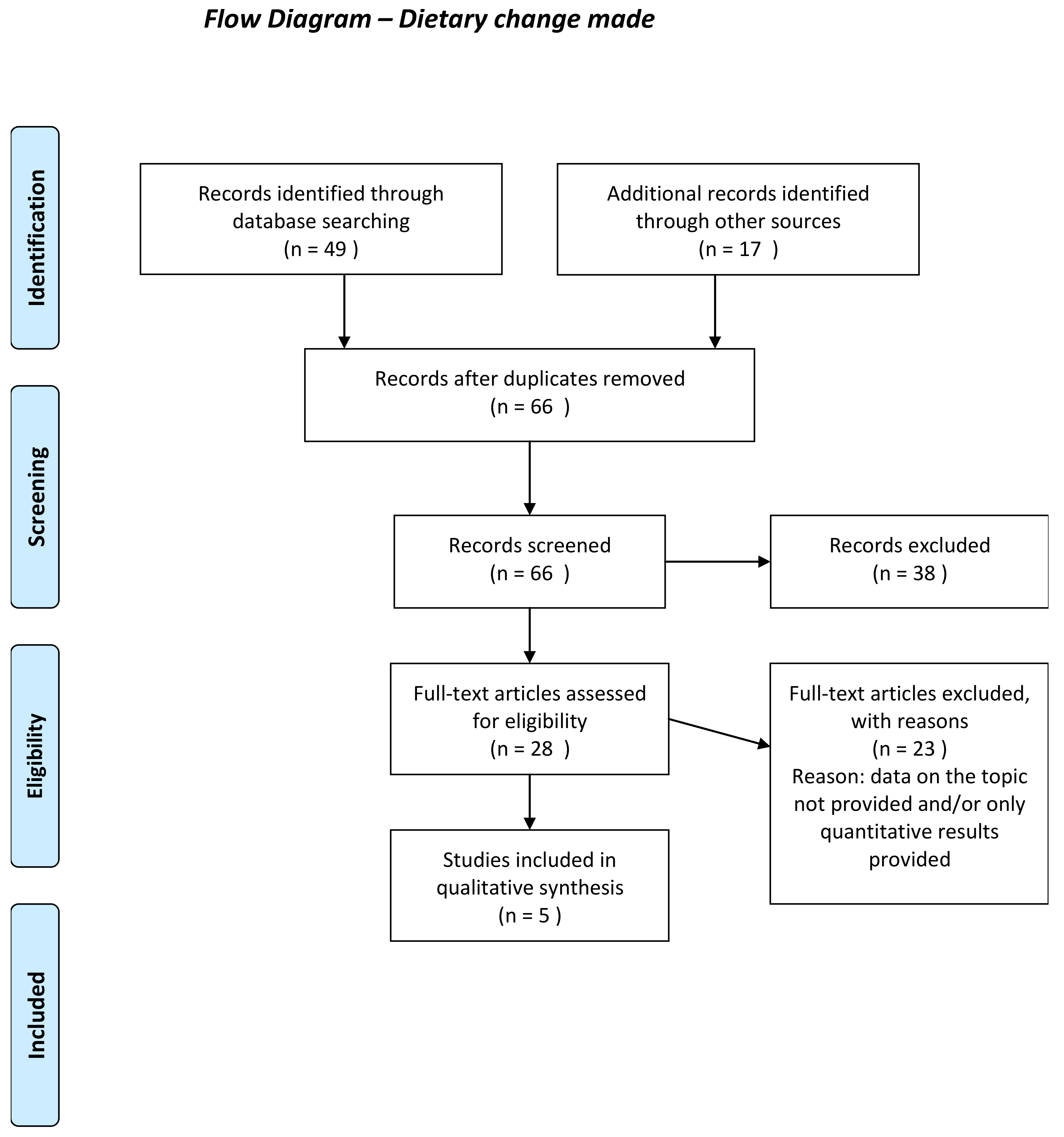

3.1. Studies Included and their Characteristics

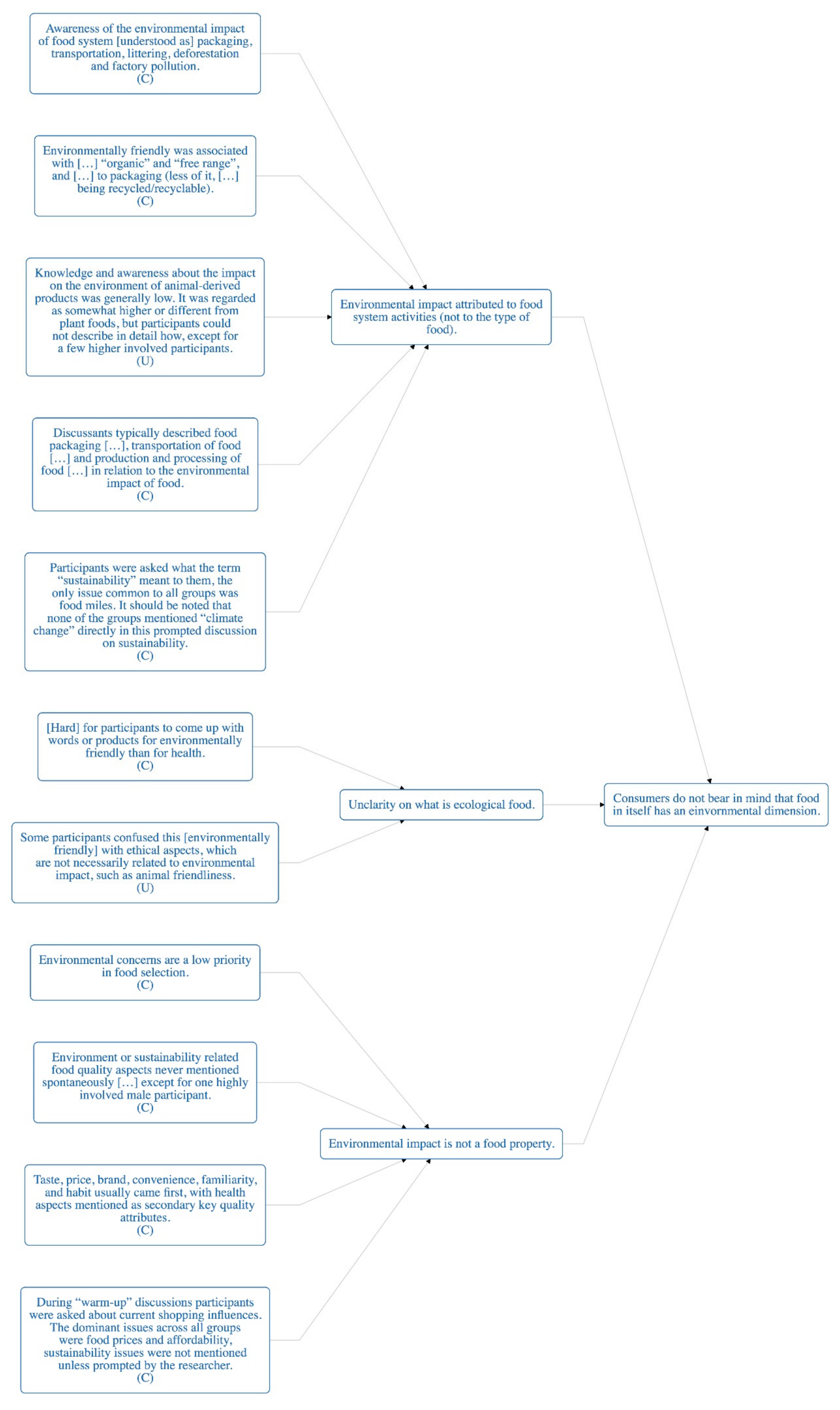

3.2. Awareness

3.3. Willingness

3.4. Change

4. Discussion

Recommendations

- Prepare consumers to understand that meat has an environmental impact by (1) informing that food, in general, has an environmental dimension, (2) addressing the positive image of meat consumption among consumers (strategies need to be found in order to persuade consumers that meat is not as good as they believe, (3) addressing skepticism towards the effectiveness of personal dietary change.

- Investigate consumers’ information sources. It would be necessary to compare information sources and credibility attributed to them for consumers already aware and not yet aware.

- Research how to overcome consumers’ beliefs and perceptions (barriers) that make it difficult for them to acknowledge the environmental impact of meat.

- Consumers need to feel nutritionally safe and enjoy their meals. Nutritional and culinary education on meatless diets may increase consumers’ willingness to reduce their meat consumption.

- Quantitative studies have shown that when prior information about the environmental impact of meat is given, willingness to reduce meat consumption increases. However, this could be attributed to social desirability. It would be necessary to observe if prior nutritional and culinary education would be more effective than prior information in increasing people’s willingness to reduce meat consumption.

- Since health/nutritional, economic, and taste reasons can be both enablers and barriers depending on who is asked, it is necessary to find out the social covariates that correlate with these reasons as enablers and barriers to reduce meat consumption.

- Link personal and animal health to planetary health (since personal health and animal welfare are the most prevalent motives to become vegetarian).

- Conduct qualitative investigations on meat-reducers and flexitarians.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Characteristics of Included Studies - Interpretive and Critical Research Form [23].

| Study | Methods for Data Collection and Analysis | Country | Phenomena of Interest | Setting/Context/Culture | Participant Characteristics and Sample Size | Description of Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell J, Macdiarmid J, Douglas F. 2016. [27] | Focus groups. Grounded Theory, thematic analysis. | Scotland | Young people’s perceptions of the environmental impact of the food system and their willingness or openness to the idea of reducing meat consumption for the sake of the environment. Awareness of the environmental impact of the food system. | North East Scotland Schools in rural and urban areas | 14 focus groups (n = 103). Ages: 12–15 yrs. old. All socioeconomic groups. | "[there was] awareness of the environmental impact of the food system, which was commonly associated with excessive food packaging, the transportation of foods from other countries, environmental damage of littering, deforestation and factory pollution. Meat was rarely mentioned as a contributor, but when prompted some participants mentioned methane gas produced by cows and deforestation.” “environmental concerns are a low priority in food selection decisions with taste and enjoyment, price, desire for satiety and health properties the more salient issues.” |

| Hoek A, Pearson D, James S, Lawrence M, Friel S. 2017. [28] | Qualitative Web-based interview. Semi-structured virtual face-to-face in-depth interviews. Projective techniques | Australia | The subjective experiences and perceptions of consumers regarding healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviors. 1) Choose and describe three food products. 2) Open question regarding the following statement and others: Do not eat too many animal-derived products and eat more plant-based foods | Participants were recruited via a professional market research agency from their opt-in consumer research panel | 29 participants with different degrees of involvement with healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviors | 1) Environment or sustainability-related food quality aspects were never mentioned spontaneously in the first phase of the interview, except for one highly involved male participant. 2) Knowledge and awareness about the impact on the environment of animal-derived products were generally low. |

| Macdiarmid JI, Douglas F, Campbell J. 2016. [29] | Grounded Theory; Thematic analysis; Focus groups. | Scotland | Public awareness of the environmental impact of food. Show agreement or disagreement with: “some people think what we eat is contributing to climate change” and second “some people think that eating less meat would be good for the environment”. | Rural and urban setting in Scotland | 87 participants. Age: > 24. 46% Men. Mixed sex. From high and low socio-economic areas | A lack of awareness of the association between meat consumption and climate change. Environmental impact of food associated with food system processes. Mixed response to the statement: “some people think that eating less meat would be good for the environment”. Perceptions of personal meat consumption playing a minimal role in the global context of climate change. |

| O’Keefe L, McLachlan C, Gough C, Mander S, Bows-Larkin A. 2016. [30] | 6 focus groups. Iterative coding. Practice theory. | England | Consumer responses to potential changes in food-related practices to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Discussion around "Eating less meat" | Greater Manchester area | N = 40 (21 males) general population. | Initial discussions with respondents indicated that climate change and sustainability did not feature in the current meanings associated with food or in purchasing decisions. When asked to reduce meat consumption by 20%, only a minority discussed the environmental impact of eating meat. |

| Study | Methods for Data Collection and Analysis | Country | Phenomena of Interest | Setting/Context/Culture | Participant Characteristics and Sample Size | Description of Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell J, Macdiarmid J, Douglas F. 2016. [27] | Focus groups. Grounded Theory, thematic analysis. | Scotland | Young people’s perceptions of the environmental impact of the food system and their willingness or openness to the idea of reducing meat consumption for the sake of the environment. Reducing meat consumption for environmental benefit | North East Scotland Schools in rural and urban areas | 14 focus groups (n = 103). Ages: 12–15 yrs. old. All socioeconomic groups. | A general resistance based on health and social reasons was found to reducing meat consumption for environmental benefit. |

| O’Keefe L, McLachlan C, Gough C, Mander S, Bows-Larkin A. 2016. [30] | 6 focus groups. Iterative coding. Practice theory. | England | Consumer responses to potential changes in food-related practices to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Discussion around "Eating less meat" | Greater Manchester area | N = 40 (21 males) general population. | Only a minority discussed the environmental impact of eating meat, when asked to reduce meat consumption in a 20% |

| Macdiarmid JI, Douglas F, Campbell J. 2016. [29] | Grounded Theory. Thematic analysis. Focus groups. | Scotland | Public awareness of the environmental impact of food. -1) ‘Would you be willing to reduce the amount of meat you eat? 2) Why (yes or not)? | Rural and urban setting in Scotland | 87 participants. Age: > 24. 46% Men. Mixed sex. From high and low socio-economic areas | Majority said no because meat is pleasurable, or they already eat few of it, or because they have already reduced meat consumption. Those ready to reduce meat consumption would rather do it because of health benefits. Skepticism towards scientific evidence that meat reduction is good for the environment. |

| Tucker CA. 2014. [31] | Focus groups. Frame thematic analysis. Sociodemographic and other quantifiable data statistically analyzed. | New Zealand | How individuals might respond to various meat consumption reduction strategies. Reducing meat consumption for environmental benefit. | Geographycally varied range of participants | N = 69 (32 males) (42.6% aged 36–65) (65.2% ate meat at least four times a week) | 69.7% saw favorably for New Zealanders to adopt meat curtailment strategies in order to address environmental issues. Only ten participants named the environmental benefits of reducing meat consumption. The majority referred to economic, taste, and health reasons. |

| Study | Methods for Data Collection and Analysis | Country | Phenomena of Interest | Setting/Context/Culture | Participant Characteristics and Sample Size | Description of Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beardsworth A, Keil E. 1991. [36] | Semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis. | United Kingdom | The motivations, beliefs, and attitudes of practicing vegetarians. Identify the single most important motive for vegetarianism or veganism. | Not specified | N = 76 self-defined as vegetarians or vegans and not members of ethnic groups in which some form of vegetarianism is customary practice. Age = 16 or older. (Majority 26–35 years old). Substantial proportion of participants were professional and white-collar workers. | Ecological concerns, related to arguments about the environmental aspects of animal husbandry, were indicated as a principal motive by just one respondent. |

| Fox N, Ward K. 2008. [35] | Online ethnographic research in participants from an international message board. Open-ended survey plus follow-up interviews. Data analyzed thematically using framework analysis. | International | The motivations of vegetarians. Open-ended questions designed to elicit participants’ motivations for vegetarianism, attitudes to meat-eating, health and animal welfare, and related life-style choices. | Online Westerners | International, mainly from North America, UK and Australasia. N = 33 questionnaire N = 18 follow-up e-mail interviews. 70% = females Age = 14–53 yrs. old. Median = 26 Vegans and vegetarians. | Only 1 respondent had become vegan for explicitly environmental motivations. For both health and ethical vegetarians, environmental concerns had become important, even though they were not the initial motivation for their dietary choices. |

| Menzies K, Sheeshka J. 2012. [32] | Semistructured interviews. Type of analysis: accurate description. | Canada | The experience, reasons, and contexts associated with leaving vegetarianism. Reasons for vegetarianism. | University Campus | N = 15 vegetarians (9 women) and 19 exvegetarians (14 women). Ages 18–35 Mean age: 24 Mainly university students. | 7/15 vegetarians because of animal/environmental concerns 16/19 ex-vegetarians because of animal/environmental concerns. Overwhelmingly, among the ex-vegetarians, the moral concern that led them to become vegetarian was a commitment to the welfare of animals and the environment. Ex-vegetarians came to believe that ways other than avoiding meat were available to support animal and environmental welfare, such as eating limited quantities of meat or only "organically farmed" meat. |

| Potts A, White M. 2008. [33] | Open-ended questionnaires sent via email or post. Thematic analysis. | New Zealand | Key antecedents to becoming vegetarian, early personal impressions on human-animal relationships, and the experience of being a vegetarian kiwi. List influences and antecedents for avoiding meat, and/or other animal-derived products. | 93% of participants lived in urban environments, although 34% had grown up on or around farms | N = 155 (35 men) Women aged 14–85 (mean age = 39; median age = 39); Men aged 19–71 (mean age = 45; median age = 44). 38% of participants (44 women and 16 men) classified as vegan; 37% as ovo-lacto vegetarians (42 women and 15 men); 7.5% as ovo-vegetarians (9 women and 3 men); 7.5% as lacto-vegetarians (10 women and 2 men); 5% as pescatarians (7 women and 1 man); and 8 as meat-eaters (all women). | Environmental reasons were listed by a total of 13 participants. |

| Testoni I, Ghellar T, Rodelli M, De Cataldo L, Zamperini A. 2017. [34] | Individual face-to-face interviews. Phenomenological Analysis and grounded ethnographic method. | Italy | Whether vegetarianism is symbolically mediated by disgust and whether this emotion ostensibly prevents us from being afraid of death. Reasons for adopting a vegetarian or vegan diet. | Northern and Central Italy. Formal and informal meetings (food-related gatherings, spiritual and prayer meetings). | N = 22 (12 women) Vegetarians 55% Vegans 45% | Ecological concerns were not the reason for refusing meat. However, this reason appeared in all narrations assuming a tripartite form: as 1) a way to help protect the planet, 2) a way to achieve environmental equilibrium, and 3) as part of affective and philosophical reasons evoking transcendence and spirituality. |

Appendix B

| Citation | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beardsworth A, Keil E. 1991. [36] | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Campbell J, Macdiarmid J, Douglas F. 2016. [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Fox N, Ward K. 2008. [35] | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Hoek A, Pearson D, James S, Lawrence M, Friel S. 2017. [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Macdiarmid JI, Douglas F, Campbell J. 2016. [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Menzies K, Sheeshka J. 2012. [32] | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| O’Keefe L, McLachlan C, Gough C, Mander S, Bows-Larkin A. 2016. [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N/A | U | Y |

| Potts A, White M. 2008. [33] | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Testoni I, Ghellar T, Rodelli M, De Cataldo L, Zamperini A. 2017. [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Tucker CA. 2014. [31] | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| Question | Yes | No | Unclear | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | ||||

| 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | ||||

| 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | ||||

| 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | ||||

| 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | ||||

| 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | ||||

| 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | ||||

| 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | ||||

| 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | ||||

| 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | ||||

| INCLUDE _______________ EXCLUDE_____________________ | ||||

Appendix C: List of Study Findings with Illustrations

| Study: Campbell 2016 [27] - Awareness | |

| Finding | Awareness of the environmental impact of the food system [understood as] packaging, transportation, littering, deforestation and factory pollution. (C) |

| Finding | Meat rarely mentioned as a contributor […] prompted participants mentioned methane gas produced by cows and deforestation. (C) |

| Finding | Environmental concerns are a low priority in food selection (C) |

| Study: Hoek 2017 [28] -Awareness | |

| Finding | Environment or sustainability-related food quality aspects never mentioned spontaneously […] except for one highly involved male participant. (C) |

| Finding | Taste, price, brand, convenience, familiarity, and habit usually came first, with health aspects mentioned as secondary key quality attributes. (C) |

| Finding | Environmentally friendly was associated with […] “organic” and “free-range”, and […] to packaging (less of it, […] being recycled/recyclable). (C) |

| Finding | [Hard] for participants to come up with words or products for environmentally friendly than for health (C) |

| Finding | Some participants confused this [environmentally friendly] with ethical aspects, which are not necessarily related to environmental impact, such as animal friendliness. (U) |

| Illustration | Low involved female, age 61: …Well I’m sort of environmentally, I look towards our poor little creatures, our chickens and how, if they’re barn-laid or caged, and I just think those poor little animals. And yeah, I gotta tend to agree, I do pay a little bit for eggs and that. Just I suppose that’s peace of mind, more so than you get anything else. |

| Finding | Knowledge and awareness about the impact on the environment of animal-derived products were generally low. It was regarded as somewhat higher or different from plant foods, but participants could not describe in detail how, except for a few higher involved participants. (U) |

| Illustration | Interviewer: Do you think there that animal products have the same impact on the environment as plant foods? Medium involved male, age 64: Not exactly the same, but they’re going to have an impact on the environment in a different way. If you’ve got cattle grazing there…they have to eat the grass, but whether that changes the environment that much I don’t know much. |

| Finding | Meat production was not associated with the food industry and intensive production processes, but discussed more along the lines of small scale farming with cows and sheep grazing in the field, although some did reflect on animal welfare issues. (U) |

| Illustration | Medium involved male, age 64: Not exactly the same, but they’re going to have an impact on the environment in a different way. If you’ve got cattle grazing there…they have to eat the grass, but whether that changes the environment that much I don’t know much. |

| Study: Macdiarmid 2016 [29] - Awareness | |

| Finding | Discussants typically described food packaging […], transportation of food […] and production and processing of food […] in relation to the environmental impact of food. (C) |

| Finding | The environmental impact of meat production or its contribution to climate change was rarely spontaneously mentioned, (C) |

| Finding | Those who agreed with the statement [“some people think that eating less meat would be good for the environment”] were inclined to associate eating meat with deforestation and methane produced by cattle, (C) |

| Finding | Perceptions of personal meat consumption playing a minimal role in the global context. It was viewed by some that personally eating less meat would make very little difference to climate change mitigation. Within this theme two sub-themes emerged; i. personally unable to make a difference (me vs. others), and ii. bigger environmental issues (it is bigger than food). (U) |

| Illustration | “no, you know, you say well does not having a steak today help because it takes thousands of other people to do the same thing and how do you convince them? No I don’t think I would change either, it’s selfish but …” (M, LD, U) “it’s all to do with the population as well, in certain countries like India and obviously China, as well and they’re having an impact.” (M, HD, U) |

| Finding | The statement [“some people think that eating less meat would be good for the environment”] produced an emotive response evident by body language where participants strongly disagreed with the statement. Some […] expressed skepticism about the scientific evidence or were simply unconvinced by the argument, Others believed that compared with other behaviors meat consumption was trivial or that regardless of the impact meat was an essential component of our diet, for health reasons and tradition. A few participants had not considered the link between food/meat and the environment before coming to the group and said that they would want more evidence before they would accept the statement. (U) |

| Illustration | As illustrated by one woman, “Because I dunnae [don’t] see where their arguments is coming from [eating less meat]. Nobody’s convinced me otherwise”(W,HD,U). “If someone said meat is poor for the environment I would ask for a heck of a lot of information and material to convince me that that is a big issues, certainly compared to the rest of things in the world.” (M, LD, R) |

| Study: O’Keefe 2016 [30] - Awareness | |

| Finding | During “warm-up” discussions participants were asked about current shopping influences. The dominant issues across all groups were food prices and affordability, sustainability issues were not mentioned unless prompted by the researcher. (C) |

| Finding | Participants were asked what the term “sustainability” meant to them, the only issue common to all groups was food miles. It should be noted that none of the groups mentioned “climate change” directly in this prompted discussion on sustainability. (C) |

| Study: Campbell 2016 [27] - Willingness | |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] Participants expressed concern that reducing meat intake may be detrimental to human health as a result in not getting enough nutrients, especially protein. (C) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] They did not want to eat less meat due to the pleasure [of eating meat]. (C) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] They did not want to eat less meat due to the […] central place meat represented in their daily diet. (C) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] not wanting to eat differently from family or friends. (C) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] being concerned about the lack of palatable alternatives (C) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] they did not eat much meat anyway and there was no need to cut down. (C) |

| Study: O’Keefe 2016 [30] - Willingness | |

| Finding | [Price] Animal welfare issues were often mentioned alongside price and quality in discussions around respondents’ current reasons for reducing [20%] meat consumption. (U) |

| Illustration | “I’ve stopped buying meat because of the price, but also because of the way that it gets from being alive to on your plate. I’m not sure I’m particularly comfortable with that”. |

| Finding | Only a minority may reduce 20% meat consumption motivated by environmental reasons (U) |

| Illustration | Only a minority discussed the emissions implications (i.e., environmental impact) of eating meat: “Meat has the highest carbon emissions by such, you know, a high level. And meat: “Meat has the highest carbon emissions by such, you know, a high level." |

| Finding | Predicted reluctance by other family members was perceived as one of the biggest barriers to this 70% reduction. [Social reasons] (U) |

| Illustration | Females considered men in their families would find both a 20% and 70% reduction in meat consumption problematic: “I’d be happy to eat less meat but my husband likes to have meat on every dinner”. Males, however, expressed similar levels of personal willingness to reduce meat consumption. |

| Finding | Parents reported they would be happy to reduce [70%] meat consumption for themselves but not for their children, due to their perceptions of the role of meat in satisfying nutritional needs. (U) |

| Illustration | I prefer them to eat meat cause when they do they’re more full and I know they’re getting a proper meal inside them. |

| Finding | Participants discussed barriers to making the 70% reduction which included the need to develop new competences, expressed as a lack of awareness of reduced-meat recipes and the perceived effort involved in making vegetarian meals. (C) |

| Finding | [Lack of meat associated with being poor as resistance to a 70% meat intake reduction] (U) |

| Illustration | ... introducing additional meanings associated with meat consumption: “They’d say, ‘Mum, are you poor? Where is our meat? |

| Finding | Participants spoke of having grown up with traditional “meat and two veg” meals. [as resistance to 70% meat reduction] (U) |

| Illustration | Participants spoke of having grown up with traditional “meat and two veg” meals. |

| Finding | Participants […] felt unsure of how to incorporate satisfying meat-free meals into their diet concerned that reducing meat to such an extent [70%] would result in boring and repetitive meal times (U) |

| Illustration | “So if someone who eats a lot of meat like myself who doesn’t eat particularly a lot of veg, what would you eat then?” |

| Finding | Respondents stressed the need to be given positive messages on what could be eaten rather than simply being told not to eat meat [when asked for a 70% reduction]. (U) |

| Illustration | “If a campaign was like don’t eat meat twice a week, I think a lot of people would go, ‘So I starve for two days a week? You have to give people an alternative” |

| Finding | A 70% meat reduction was frequently referred to as a “vegetarian” diet by participants. (C) |

| Finding | [Animal Welfare] Animal welfare issues were often mentioned alongside price and quality in discussions around respondents’ current reasons for reducing [20%] meat consumption. (U) |

| Illustration | “I’ve stopped buying meat because of the price, but also because of the way that it gets from being alive to on your plate. I’m not sure I’m particularly comfortable with that”. |

| Study: Macdiarmid 2016 [29] - Willingness | |

| Finding | Three sub-themes emerged in the accounts of why people were not willing to eat less meat. i. Meat is pleasurable... (U) |

| Illustration | “It’s nothing to do with [disliking] the vegetables, I just like meat.” (M, HD, R). |

| Finding | Three sub-themes emerged in the accounts of why people were not willing to eat less meat. i. Meat is [...] social (C) |

| Finding | Three sub-themes emerged in the accounts of why people were not willing to eat less meat. i. Meat is [...] traditional. (C) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] (e.g., a proper meal has to include meat, meat fills you up), (U) |

| Illustration | “it’s not just me that’s eating meat in my house. My husband’s a bit of a ‘it’s not a meal unless it has meat in it’.” (W, LD, U) |

| Finding | [Resistance to meat reduction because of the environment…] it is part of a healthy diet… (C) |

| Finding | Some participants claimed that they only ate small quantities of meat and therefore did not need to reduce their consumption. (U) |

| Illustration | “I think we eat the right amount, as well, we don’t overindulge, we don’t have meat every night or whatever, but when we do have it it’s good, local, locally sourced as much as possible, but I wouldn’t like to eat any less.” (W, LD, R) |

| Finding | Those who claimed to have already reduced their meat intakes (particularly red meat) believed that they did not need to reduce it further. Reasons given for cutting down meat included health concerns, food scares (e.g., CJD, horse meat scandal), the high cost of meat, living with a partner who was vegetarian or changing dietary habits with aging. (C) |

| Finding | The minority who said that they would consider eating less meat were more inclined to do this for health benefits rather than environmental gains. (C) |

| Finding | Would only be willing [to reduce meat consumption] if there was evidence to support it would be beneficial [for the environment]. (U) |

| Illustration | “I’d eat less but they’d have to prove to me that it was going to make a difference.” |

| Finding | Some of those who thought they might be persuaded to cut down their meat consumption said that they would not know what to replace it with, which was seen as a potential barrier. (C) |

| Finding | Reluctance to reduce meat consumption persisted as a dominant theme throughout the discussions despite awareness of the potential environmental consequences. (U) |

| Illustration | “I am aware that ruminants cause a problem with methane, that wouldn’t stop me eating meat.” (M, LD, R). |

| Finding | Other non-food pro-environmental changes were described as preferable to eating less meat... (U) |

| Illustration | “I probably won’t eat less meat. I’m aware of the environment I take other steps, fine I do my bit, recycling, driving less but I probably wouldn’t change my diet.” (M, HD, R) |

| Study: Tucker 2014 [31] - Willingness | |

| Finding | In terms of economics, most of the participants that commented noted the relatively (and increasingly) expensive cost of meat. [As a reason to reduce meat consumption] (U) |

| Illustration | “It’s heaps cheaper to eat vegetarian. I’ve seen people on TV doing household budgets, saying that you don’t have to have meat every night” (10m), and “I think meat is going to be unsustainable because the price will go up and will prompt people to eat less meat” |

| Finding | On the appeal of meatless or reduced-meat meals, participants commented on the way such meals (can) look, and also on the texture. (U) |

| Illustration | “I’d love to eat [the vegetarian meals pictured on the hand out] all the time – every night – for sure! Gorgeous!” (39f); and “I think taste for me is important, but it’s also about texture. If you’re going to buy a meat replacement, eggplant is so meaty and you don’t really have to eat meat” (47f). |

| Finding | Comments related to health or nutritional reasons in favor of a reduced meat diet tended to either extoll the virtues of more vegetables and fruits in the diet, […] or point out the health issues associated with too much meat consumption – or consumption of unhealthy meat types. (U) |

| Illustration | “More fresh vegetables in your diet makes you feel better” (8m), In our household, it’s health reasons for eating less meat because I have got diabetes. So I look now at less meat and lower fat and all that kind of stuff...you know it’s a healthy diet and it’s not like you’re missing out on anything, it’s just less...red meat and more of your lower GI carbs and things like that. (21f) |

| Finding | Environmentally, participant comments reflected concerns about the environmental implications of agricultural production (U) |

| Illustration | “I don’t think the way we eat meat on this planet is sustainable for our health or the planet. [Meat production] is a pollutant to waterways and soil” |

| Finding | Opposition to reducing meat consumption was mainly expressed in relation to […] and due to economic reasons. (C) |

| Finding | The difficulties noted with a reduced (or meatless) diet were based on three main factors: first, the notion that meat is more convenient (and meatless meals less so): Second was that many people stated they did not know how to cook (appealing) meals without meat. (U) |

| Illustration | “That’s all very well if you’ve...got the time on your hands to do it...” (39f); “Vegetarian food can be delicious, but it requires more time and knowledge” (62m) |

| Finding | A number of rationales were provided as to why meat is a necessity in the diet, including the need for animal-based healthy proteins, and why on the other hand a vegetarian diet could be bad. [...] Other reasons for opposition to a reduced meat diet included how humans are biologically meant to eat meat as omnivores, and that not eating meat can lead to ill health. (U) |

| Illustration | The vegetarian ‘cheese on cheese’ phenomenon, where everything has cheese slathered all over it...it’s not good for them. [Research] says that if you eat some meat you probably would be okay [and not get] all these cancers that people get, but if you eat a lot of cheese, dairy, you are in big trouble. (41f) |

| Finding | Another often cited reason [to resist meat curtailment] was based on satiety (and often linked to protein as well) that growing young people, and those engaged in physical labor in particular, need to have animal-based foods to get and keep them feeling full. (U) |

| Illustration | If you’ve got a young family you’ve got to think that basically they’re filling up with food for a certain length of time but not for long. It’s a bit like Chinese food; Chinese food is nice but it doesn’t last long. They’ve got to have protein to fill them, especially since they are growing, which comes back to needing meat. (20f) |

| Finding | Overall there was a firm view that it would be quite difficult to reduce meat consumption in New Zealand given that it is such an entrenched aspect of people’s lives and upbringing. (U) |

| Illustration | “...it’s probably quite engrained. We’ve been brought up with meat and there’s not a lot of advertising for other ideas and it’s so easy to slap something on the barbecue” (46f). |

| Study: Beardsworth 1991 [36] - Change | |

| Finding | Interestingly, the linkage between the idea of animal rights and human rights was made quite frequently, most often in the context of the argument that meat production for consumption in the West was an environmentally undesirable and inefficient mode of agricultural activity which condemned many Third World inhabitants to inadequate dietary standards. (C) |

| Finding | A typical pattern might involve an interviewee whose reasons for a move towards vegetarianism were primarily moral, but who was confident that s/he was also deriving health benefits from the dietary changes undertaken, and might also believe that a contribution, however small, was being made to the protection of the environment, or indeed, to the more equitable distribution of global food provision. (C) |

| Study: Fox 2008 [24] - Change | |

| Finding | Among our sample of 33 participants in the VegForum, only one respondent, 29-year-old Canadian Simon, had become vegan for explicitly environmental motivations. (U) |

| Illustration | Among our sample of 33 participants in the VegForum, only one respondent, 29-year-old Canadian Simon, had become vegan for explicitly environmental motivations, in order to ‘do something to maintain the planet’. |

| Finding | These data suggest that for both health and ethical vegetarians, environmental concerns had become important, even though they were not the initial motivation for their dietary choices. (U) |

| Illustration | Sometimes concern with the wider environment emerged directly from a perspective related to the impact of meat consumption for human or animal health. “I try and only eat organic egg and milk products, for the animal and human population health and well being. Non-organic farming of animals are breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and viruses, which can spread to humans. As well as not being very nice for the animal. I try and be environmentally friendly as I can.” |

| Finding | The ‘environmentally-friendly’ aspects of vegetarianism also often linked implicitly with a range of other non-diet behaviors concerning environmental protection. (U) |

| Illustration | I try and get organic food mostly and put a considerable amount of effort into being as environmentally friendly as possible: I recycle, try and cut down on waste, conserve energy, cycling instead of driving, etc. Most of my friends think I’m weird because in addition to the above I also refuse to eat anything with E numbers or hydrogenated oils and also boycott animal-testing companies. |

| Finding | Tim had been raised as a vegetarian, but said his move to veganism was a way to ‘do more for the environment. I just want to be as green as I can’ (U) |

| Illustration | Tim had been raised as a vegetarian, but said his move to veganism was a way to ‘do more for the environment. I just want to be as green as I can’ |

| Study: Menzies 2012 [32] - Change | |

| Finding | Most of the largely young adults embraced a vegetarian diet for ethical reasons, not health concerns. Among continuing vegetarians, the moral reasons for choosing vegetarianism were almost evenly split between a belief in animal rights […] and animal/environmental concerns […]. (C) |

| Finding | Overwhelmingly, among the ex-vegetarians, the moral concern that led them to become vegetarian was a commitment to the welfare of animals and the environment. Ex-vegetarians came to believe that ways other than avoiding meat were available to support animal and environmental welfare, such as eating limited quantities of meat or only "organically farmed" meat. (C) |

| Study: Potts 2008 [33] - Change | |

| Finding | Participants listed ethical, spiritual, and environmental reasons for avoiding meat and/or other animal-derived products. [...] environmental reasons (8% women and 4% men). There was some overlap here, as several cited multiple motives. (C) |

| Finding | These participants established a link between vegetarianism and a love for nature that fostered their thinking about nonhuman sentience. (C) |

| Study: Testoni 2017 [34] - Change | |

| Finding | Among the 22 participants in this study, different initial motivations for vegetarianism were identified: […], environmentalism, […]. (C) |

| Finding | Even though we have not found that this was the reason for refusing meat, this reason [environmental and ecological impact of meat production] always appeared in all the narrations, [of why not eating meat]. (U) |

| Illustration | Even though we have not found that this was the reason for refusing meat, this reason [environmental and ecological impact of meat production] always appeared in all the narrations, [of why not eating meat]. |

| Finding | Many participants, whose first explanations were personal health, also described a range of environmental commitments aimed at protecting the life of the Earth (U) |

| Illustration | Well, if we have a critical approach, it is far too evident; if we do not want tropical forests to be cut down, maybe, it would be better for the world not to eat meat, because we could feed much more people with field products than with meat. |

Appendix D: Flow Charts of the Different Phases of the Qualitative Synthesis Review

Appendix E: Meta-aggregative Flowcharts

References

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.D.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; Rosales, M.; De Haan, C. Livestock’s Long shadow: Environmental Issues and Options; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2006; ISBN 92-5-105571-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman, L.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Van Der Hoek, K.W.; Beusen, A.H.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Willems, J.; Rufino, M.C.; Stehfest, E. Exploring global changes in nitrogen and phosphorus cycles in agriculture induced by livestock production over the 1900–2050 period. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20882–20887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvergne, P. The Shadows of Consumption: Consequences for the Global Environment; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-262-04246-8. [Google Scholar]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, P.K. Livestock production: Recent trends, future prospects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2853–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slingo, J.M.; Challinor, A.J.; Hoskins, B.J.; Wheeler, T.R. Introduction: Food crops in a changing climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; O’Riordan, T. The sustainability challenges of our meat and dairy diets. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2015, 57, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, K.J.; Kraan, C.M.; Adger, W.N.; Buhaug, H.; Burke, M.; Fearon, J.D.; Field, C.B.; Hendrix, C.S.; Maystadt, J.-F.; O’Loughlin, J. Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict. Nature 2019, 571, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C. IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ruini, L.; Ciati, R.; Marchelli, L.; Rapetti, V.; Pratesi, C.A.; Redavid, E.; Vannuzzi, E. Using an Infographic tool to promote healthier and more sustainable food consumption: The Double Pyramid Model by Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Segovia-Siapco, G.; Sabaté, J. Health and sustainability outcomes of vegetarian dietary patterns: A revisit of the EPIC-Oxford and the Adventist Health Study-2 cohorts. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, J.; Ruby, M.B.; Loughnan, S.; Luong, M.; Kulik, J.; Watkins, H.M.; Seigerman, M. Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite 2015, 91, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabate, J.; Soret, S. Sustainability of plant-based diets: Back to the future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 476S–482S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleschuk, M.; Johnston, J.; Baumann, S. Maintaining Meat: Cultural Repertoires and the Meat Paradox in a Diverse Sociocultural Context. Sociol. Forum 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 0-470-43248-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer Attitudes Towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, C.; Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Using qualitative research synthesis to build an actionable knowledge base. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hannes, K.; Lockwood, C. Synthesizing Qualitative Research: Choosing the Right Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-119-95982-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Roberts, K. Including qualitative research in systematic reviews: Opportunities and problems. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2001, 7, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Porrit, K.; Munn, Z.; Rittenmeyer, L.; Salmond, S.; Bjerrum, M.; Loveday, H.; Carrier, J.; Stannard, D. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- JBI SUMARI. Available online: http://www.jbisumari.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Chapter 1: JBI Systematic Reviews. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garip, G.; Yardley, L. A synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people’s views and experiences of weight management. Clin. Obes. 2011, 1, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.; Macdiarmid, J.I.; Douglas, F. Young people’s perception of the environmental impact of food and their willingness to eat less meat for the sake of the environment: A qualitative study. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, E224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Pearson, D.; James, S.W.; Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S. Shrinking the food-print: A qualitative study into consumer perceptions, experiences and attitudes towards healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviours. Appetite 2017, 108, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.I.; Douglas, F.; Campbell, J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite 2016, 96, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, L.; McLachlan, C.; Gough, C.; Mander, S.; Bows-Larkin, A. Consumer responses to a future UK food system. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.A. The significance of sensory appeal for reduced meat consumption. Appetite 2014, 81, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, K.; Sheeshka, J. The Process of Exiting Vegetarianism: An Exploratory Study. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2012, 73, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, A.; White, M. New Zealand Vegetarians: At Odds with Their Nation. Soc. Anim. 2008, 16, 336–353. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Ghellar, T.; Rodelli, M.; De Cataldo, L.; Zamperini, A. Representations of Death among Italian Vegetarians: An Ethnographic Research on Environment, Disgust and Transcendence. Eur. J. Psychol. 2017, 13, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fox, N.; Ward, K. Health, ethics and environment: A qualitative study of vegetarian motivations. Appetite 2008, 50, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsworth, A.D.; Keil, E.T. Vegetarianism, Veganism, and Meat Avoidance: Recent Trends and Findings. Br. Food J. 1991, 93, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Pursuing a Low Meat Diet to Improve Both Health and Sustainability: How Can We Use the Frames that Shape Our Meals? Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylan, J. Sustainable consumption in everyday life: A qualitative study of UK consumer experiences of meat reduction. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Godinho, C.A.; Truninger, M. Reducing meat consumption and following plant-based diets: Current evidence and future directions to inform integrated transitions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussar, K.M.; Harris, P.L. Children who choose not to eat meat: A study of early moral decision-making. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, J.; Devine, C.M.; Sobal, J. Model of the process of adopting vegetarian diets: Health vegetarians and ethical vegetarians. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, R.J.; Tilston, C.H.; Gregson, K.; Stagg, T. Women vegetarians: Lifestyle considerations and attitudes to vegetarianism. Nutr. Food Sci. 1993, 93, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, A.; Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Consumer Response to Negative Information on Meat Consumption in Germany. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dagevos, H.; Voordouw, J. Sustainability and meat consumption: Is reduction realistic? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Schoesler, H.; Aiking, H. Towards a reduced meat diet: Mindset and motivation of young vegetarians, low, medium and high meat-eaters. Appetite 2017, 113, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018, 131, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Brussels DG Communication COMM A1 ´Research and Speechwriting´. Flash Eurobarometer 367—Attitudes of Europeans towards Building the Single Market for Green Products; GESIS Data Archive: Cologne, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schosler, H.; De Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J.; Aiking, H. Meat and masculinity among young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2015, 89, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwatt, H.; Sabaté, J.; Eshel, G.; Soret, S.; Ripple, W. Substituting beans for beef as a contribution toward US climate change targets. Clim. Chang. 2017, 143, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, J.; Sranacharoenpong, K.; Harwatt, H.; Wien, M.; Soret, S. The environmental cost of protein food choices. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2067–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Term | Operator | Term | Operator | Term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWARENESS | ||||

| consumer attitudes | AND | Meat | AND | climate change |

| GHG emissions | ||||

| consumer perceptions | global near/2 warming | |||

| people attitudes | livestock | environment | ||

| people perceptions | water near/3 use | |||

| land near/3 use | ||||

| WILLINGNESS | ||||

| consumer willingness | AND | “plant-based” near/3 diet | AND | climate change |

| vegetarian diet | GHG emissions | |||

| vegan diet | global near/2 warming | |||

| people willingness | meatless diet | environment | ||

| water near/3 use | ||||

| “less meat” | land near/3 use | |||

| CHANGE | ||||

| “Plant-based” near/3 diet | AND | reason | AND | environment |

| vegetarian near/3 diet | ||||

| vegan near/3 diet | climate change | |||

| meatless near/3 diet | motivation | |||

| “less meat” near/3 consumption | global warming | |||

| vegetarians | ||||

| vegans | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Badilla-Briones, Y.; Sabaté, J. Understanding Attitudes towards Reducing Meat Consumption for Environmental Reasons. A Qualitative Synthesis Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226295

Sanchez-Sabate R, Badilla-Briones Y, Sabaté J. Understanding Attitudes towards Reducing Meat Consumption for Environmental Reasons. A Qualitative Synthesis Review. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226295

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez-Sabate, Ruben, Yasna Badilla-Briones, and Joan Sabaté. 2019. "Understanding Attitudes towards Reducing Meat Consumption for Environmental Reasons. A Qualitative Synthesis Review" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226295

APA StyleSanchez-Sabate, R., Badilla-Briones, Y., & Sabaté, J. (2019). Understanding Attitudes towards Reducing Meat Consumption for Environmental Reasons. A Qualitative Synthesis Review. Sustainability, 11(22), 6295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226295