Servant Leadership and Innovative Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis of Ghana’s Manufacturing Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

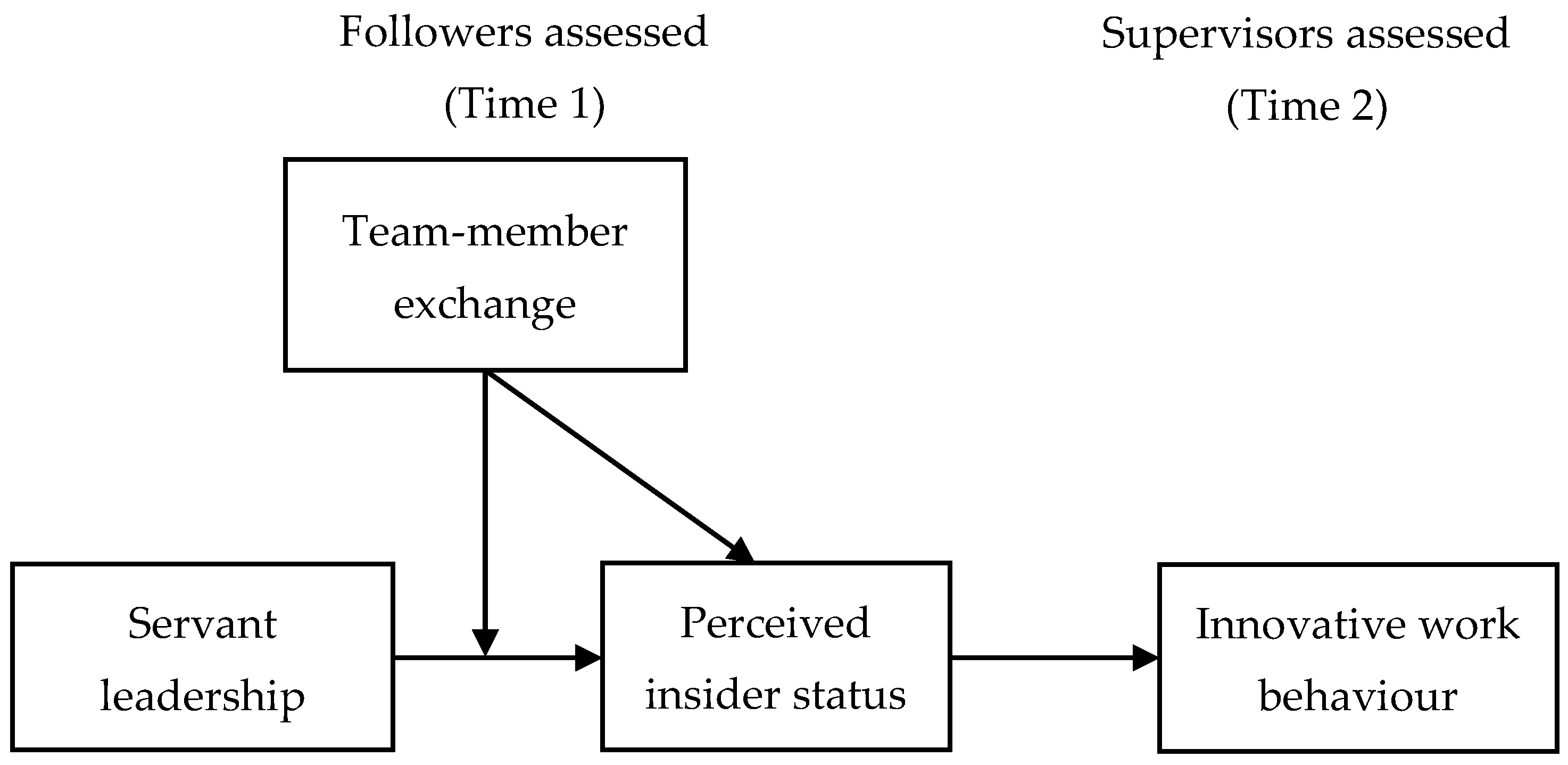

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Servant Leadership and Innovative Work Behaviour

2.2. Servant Leadership and Perceived Insider Status

2.3. The Mediating Role of Perceived Insider Status

2.4. TMX and Perceived Insider Status

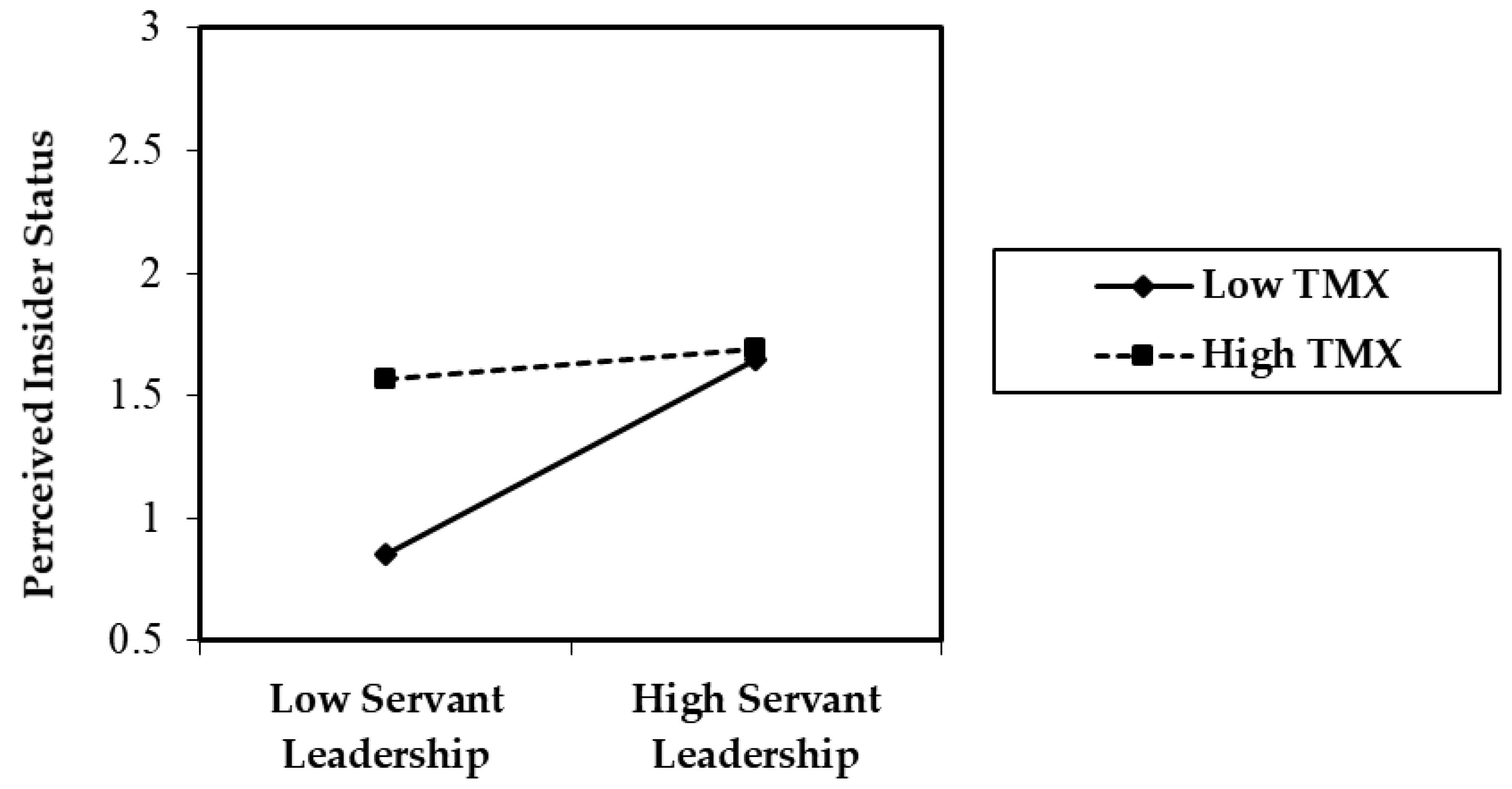

2.5. The Moderating Role of TMX on the Relationship between Servant Leadership and Perceived Insider Status

2.6. The Moderating Mediation Role of TMX

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Servant Leadership

3.2.2. Perceived Insider Status

3.2.3. Team-Member Exchange

3.2.4. Innovative Work Behaviour

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Common Method Bias

3.4. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Chi-Square Difference Test

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1.

- Servant Leadership (α = 0.88); [57].

- My leader can tell if something work-related is going wrong.

- My leader makes my career development a priority.

- I would seek help from my leader if I had a personal problem.

- My leader emphasises the importance of giving back to the community.

- My leader puts my best interests ahead of his/her own.

- My leader gives me the freedom to handle difficult situations in the way that I feel is best.

- My leader would not compromise on ethical principles in order to achieve success.

- 2.

- Perceived Insider Status (α = 0.86); [19].

- I feel very much a part of my work organisation.

- My work organisation makes me believe that I am included in it.

- I feel like I am an “outsider” at this organisation.

- I don’t feel included in this organisation.

- I feel I am an “insider” in my work organisation.

- My work organisation makes me frequently feel “left out.”

- 3.

- Innovative Work Behaviour (α = 0.84); [59].

- This employee searches out new working methods, techniques or instruments.

- This employee mobilises support for innovative ideas.

- This employee transforms innovative ideas into useful applications.

- 4.

- Team-Member Exchange (α = 0.74); [58].

- I often ask others for help.

- Members on this team willingly suggest better work methods to others.

- Other members on this team recognise my potential.

- 5.

- Competence (α = 0.72); [61].

- I am confident about my ability to do my job.

- I am self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities.

- I have mastered the skills necessary for my job.

References

- Anderson, N.; de Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A. The routinization of innovation research: A constructively critical review of the state-of-the-science. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Picken, J.C. Changing roles: Leadership in the 21st century. Organ. Dyn. 2000, 28, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuveloo, R.; Ping, T.A. Achieving business sustainability via I-TOP model. Am. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2013, 15, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, P.A. Sustainability and organizational activities–three approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.; den Hartog, D. Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2010, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, M.M.; Neff, N.L.; Farr, J.L.; Schwall, A.R.; Zhao, X. Predictors of individual-level innovation at work: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 5, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, A.N.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.; Stam, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yidong, T.; Xinxin, L. How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeler, C.K.; Shipman, A.S.; Mumford, M.D. Managing the innovative process: The dynamic role of leaders. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2011, 51, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J.; Oldham, G.R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? J. Manag. 2004, 30, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y. The Influence of Managerial Mindfulness on Innovation: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R. The Servant as Leader; The Robert K. Greenleaf Center: Newton Centre, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Eva, N.; Robin, M.; Sendjaya, S.; van Dierendonck, D.; Liden, R.C. Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D.; Stam, D.; Boersma, P.; De Windt, N.; Alkema, J. Same difference? Exploring the differential mechanisms linking servant leadership and transformational leadership to follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 544–562. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, G.A.; Russell, R.F.; Patterson, K. Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2004, 25, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behaviour: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamper, C.L.; Masterson, S.S. Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 875–894. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.C.; Jien, J.-J.; Lin, J. Antecedents and consequences of psychological contract breach. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M.J.; Hunter, E.M.; Tolentino, R.C. A servant leader and their stakeholders: When does organizational structure enhance a leader’s influence? Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccio, A.; Henderson, D.J.; Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Cao, X. Toward an understanding of when and why servant leadership accounts for employee extra-role behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Schaubroeck, J.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J. Organizational creativity research: A historical overview. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, J.P.J. How leaders influence employees’ innovative behaviour. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2007, 10, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, D.T.; Sendjaya, S.; Hirst, G.; Cooper, B. Does servant leadership foster creativity and innovation? A multi-level mediation study of identification and prototypicality. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Masterson, S.S.; Stamper, C.L. Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee–organization relationship. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behavior. 2003, 24, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; de Gilder, D.; Haslam, S.A. Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Chen, Z.; Cheung, S.Y. Applying uncertainty management theory to employee voice behavior: An integrative investigation. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 283–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Meal, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W. An essay on organizational citizenship behavior. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1991, 4, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Aryee, S. Delegation and employee work outcomes: An examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N. Linking Transformational Leadership with Nurse-Assessed Adverse Patient Outcomes and the Quality of Care: Assessing the Role of Job Satisfaction and Structural Empowerment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokay, Ö.; Eyupoglu, S.Z. Employee perceptions of organisational democracy and its influence on organisational citizenship behaviour. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Sparrowe, R.T. An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Liu, D.; Loi, R. Looking at both sides of the social exchange coin: A social cognitive perspective on the joint effects of relationship quality and differentiation on creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1090–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapalme, M.È.; Stamper, C.L.; Simard, G.; Tremblay, M. Bringing the outside in: Can “external” workers experience insider status? J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 919–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Batchelor, J.H.; Seers, A.; O’Boyle, E.H., Jr.; Pollack, J.M.; Gower, K. What does team–member exchange bring to the party? A meta-analytic review of team and leader social exchange. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; van Dyne, L.; Kamdar, D. The Contextualized Self: How Team–Member Exchange Leads to Coworker Identification and Helping OCB. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, C.I.; Lanaj, K.; Ilies, R. Resource-based contingencies of when team–member exchange helps member performance in teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1117–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I.; Janssen, O. Understanding employee innovative behavior: Integrating the social network and leader–member exchange perspectives. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.Z.; Cross, R. The strength of weak ties you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 1477–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, A.; Mclean, E.R. Expertise integration and creativity in information systems development. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort—Reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Shalley, C.E. The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic social network perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Shen, Y.M.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Chen, Q.; See, L.C. Effects of Co-Worker and Supervisor Support on Job Stress and Presenteeism in an Aging Workforce: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokisaari, M. The role of leader–member and network relations in newcomers’ role performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTernan, W.; Dollard, M.; Tuckey, M.; Vandenberg, R. Enhanced Co-Worker Social Support in Isolated Work Groups and Its Mitigating Role on the Work-Family Conflict-Depression Loss Spiral. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Instrumentality, identity and social comparisons. In Social Identity and Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982; pp. 483–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kesting, P.; Ulhøi, J.P. Employee-driven innovation: Standing the license to foster innovation. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Meuser, J.D.; Hu, J.; Wu, J.; Liao, C. Servant leadership: validation of a short form of the SL-28. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Seo, Y.; Lee, K.C. Effects of task complexity on individual creativity through knowledge interaction: a comparison of temporary and permanent teams. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 42, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, S.C.; Zhang, X.A.; Morgeson, F.P.; Tian, P.; van Dick, R. Are you really doing good things in your boss’s eyes? Interactive effects of employee innovative work behavior and leader–member exchange on supervisory performance ratings. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.; Lucianetti, L. Within-individual increases in innovative behavior and creative, persuasion, and change self-efficacy over time: A social–cognitive theory perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 10, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.-J.; Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.; Hayes, A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.; Judd, C.M.; Yzerbyt, V.Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C.; Hair, J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In Sociological Methodology; Leinhart, S., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Zelditch, M., Jr. Theories of legitimacy. In The Psychology of Legitimacy: Emerging Perspectives on Ideology, Justice, and Intergroup Relations; Jost, J.T., Major, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu-Appiah, F.; Agyapong, A.; Lituchy, T.R. Leadership in Ghana. In LEAD: Leadership Effectiveness in Africa and the African Diaspora; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Hierarchical power distance in forty countries. In Organizations Alike and Unlike: Towards a Comparative Sociology of Organizations; Lammers, C.J., Hickson, D.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1979; pp. 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Martin, R.; Epitropaki, O.; Mankad, A.; Svensson, A.; Weeden, K. Effective leadership in salient groups: Revisiting leader-member exchange theory from the perspective of the social identity theory of leadership. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Lam, S.S.; Peng, A.C. Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, P.B. Different Ponds for Different Fish: A Contrasting Perspective on Team Innovation. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 51, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; di Fabio, A. Intrapreneurial Self-Capital and Sustainable Innovative Behavior within Organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Qun, W.; Shah, S.G.; Fareed, Z. Do Hierarchical Jumps in CEO Succession Invigorate Innovation? Evidence from Chinese Economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 31.98 | 5.96 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Sex (0 = M; 1 = F) a | 0.51 | 0.50 | −0.09 | ||||||||

| 3. Education b | 14.62 | 2.09 | 0.40 ** | −0.05 | |||||||

| 4. Tenure c | 3.14 | 2.25 | 0.18 ** | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| 5. Competence | 3.62 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.72 | ||||

| 6. Servant Leadership | 3.80 | 0.65 | −0.06 | −0.15 * | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.42 ** | 0.88 | |||

| 7. Team-member Exchange | 3.94 | 0.55 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.15 * | 0.01 | 0.28 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.74 | ||

| 8. Perceived Insider Status | 3.61 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.30 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.86 | |

| 9. Innovative Work Behaviour | 3.73 | 0.81 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.18 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.84 |

| Measurement Model | df | p-Value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ∆df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (hypothesised) five-factor model | 270.26 | 199 | 0.001 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.04 | ||

| Alternative 1 (four-factor model) ¹ | 365.74 | 203 | 0.000 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 95.48 ** | 4 |

| Alternative 2 (three-factor model) ² | 498.35 | 206 | 0.000 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.08 | 228.09 ** | 7 |

| Alternative 3 (two-factor model) ³ | 746.92 | 208 | 0.000 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.11 | 476.66 ** | 9 |

| Alternative 4 (one-factor model) 4 | 909.02 | 209 | 0.000 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.13 | 638.76 ** | 10 |

| Perceived Insider Status | Innovative Work Behaviour | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Controls | ||||||

| Sex | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.00 |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.00 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Tenure | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Competence | 0.31 ** | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.18 ** | −0.04 | −0.08 |

| Independent Variable | ||||||

| Servant Leadership | 0.30 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.32 ** | ||

| TMX | 0.21 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.14 * | 0.06 | ||

| Interaction | ||||||

| Servant Leadership x TMX | −0.17 * | −0.03 | ||||

| Mediator | ||||||

| Perceived Insider Status | 0.32 ** | |||||

| Model Fit | ||||||

| F | 4.49 *** | 9.68 ** | 9.49 ** | 1.98 | 9.24 ** | 10.58 ** |

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.32 |

| ΔF | 20.53 ** | 6.41 * | 26.20 ** | 11.83 ** | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.08 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Opoku, M.A.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. Servant Leadership and Innovative Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis of Ghana’s Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226273

Opoku MA, Choi SB, Kang S-W. Servant Leadership and Innovative Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis of Ghana’s Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226273

Chicago/Turabian StyleOpoku, Mavis Agyemang, Suk Bong Choi, and Seung-Wan Kang. 2019. "Servant Leadership and Innovative Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis of Ghana’s Manufacturing Sector" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226273

APA StyleOpoku, M. A., Choi, S. B., & Kang, S.-W. (2019). Servant Leadership and Innovative Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis of Ghana’s Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability, 11(22), 6273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226273