Abstract

Sustaining up-to-date land registers in the global south is an increasing concern for the protection of tenure, development of land markets and long-term sustainable planning practices and policy. It requires both the prompt reporting of land transfers and also an alignment between prevailing land rights and official recording systems. The literature on land registration highlights some effects of inheritance practices on the land register and land development. Taking these studies a step further, our research investigates how such effects evolve from the rules that guide inheritance practices using a qualitative research approach. We found that normative practices of inheritance mostly lead to communal property through numerous processes which have implications on the timing and likelihood of possible registration. Also, we found that the significance of land and buildings in the social context transcends the physical property per se and includes dimensions of spirituality and social identity. Our findings explain the misalignment between the official and social logics of property and suggest likelihood of non-reporting. We conclude that flexibility is required in recording communal rights in rural areas and that the transition to individual property is more likely in peri-urban and urban areas where the social logics of property have broken.

1. Introduction

Inheritance is multifaceted and exhibits complexities of diverse origins from customary, statutory and religious sources [1]; and it is one of the major sources of land ownership [2,3]. Across the globe including Africa, the different forms of law that regulate inheritance have been criticized over decades by scholars and development agencies for gender biases, landlessness, fragmentation and informality [4,5,6,7,8]. Although it is an area that has been widely researched and a focus for political debate, it still requires further research especially in relation to land registration. Established and well-maintained land rights registers and cadastres can provide an important basis for long-term, sustainable planning and development [9] (p. 34). Essential to this is, however, that the official information base remains up-to-date and as such reflects various forms of rights and property transfers, including inheritance.

In reality however, it is reported that inheritance transfers are seldom reported for official recording [8,10,11,12]. The non-reporting of inheritance transfers cuts across both the global north and south for different reasons. In the global north, non-reporting of inheritance transfers stems from the burden of inheritance taxes and the attempts to evade them [13]. In this context, the inheritance of property is regarded as a transfer of wealth [14,15]. In the global south including Africa, non-reporting of inheritance transfers also derives from socio-cultural practices of land transfer [8,12,16] where land inheritance is a function of multiple socio-cultural, political and economic confrontations. In this context, property systems are often rooted in a range of familial social units that function in varying degrees of relationships [17,18]. Whereas the non-reporting of inheritance transfers in the global north appears straightforward and may be addressed through technical and administrative fixes, the attempts to increase reporting of inherited land in the global south require political and economic transformations, because inheritance is regulated through a complex blend of plural legal systems [1,19,20].

Accordingly, recording land rights that derive from inheritance in the global south is not straightforward as the logics of local inheritance practices differ from the logics of the state’s recording systems. While the transfer of land by inheritance in local communities is regarded as a transfer of the physical land with its associated cultural appurtenances and spiritual beliefs, official processes of registration reduce land inheritance to a mere instance of transfer of a physical parcel. Thus, the development and sustainability of cadastres as a state-making endeavour is positioned at the confluence of society (within which land rights are produced) and the state’s bureaucratic apparatus (within which land rights are translated). Thus, to document land rights in a sustainable manner, understanding of the underlying productive social processes of land rights transfer and holding is important since they directly and indirectly influence the processes of registration and the overall maintenance of official registries.

In the literature on land registration and land development, inheritance is topical, and two schools of thought are dominant. The first school draws connections between inheritance and the apparent effects it has on land development, land markets and land registration. While some commentators of this school argue that inheritance practices are counterproductive to land information updating and land markets [8], others highlight the physical effects of inheritance such as land fragmentation [3,7,21,22]. The second school of thought highlights the connections between inheritance practices and the plural laws that regulate them [1,23,24,25]. However, neither of the two schools demonstrates how these effects are actually produced by diverse inheritance laws (statutory, customary and religious) as they manifest in practice. This is crucial to understand for the development of policy and land registration approaches that are fit-for-purpose. More specifically, there is a need to know the types of effect that different inheritance laws produce and what such effects imply for land registration in given contexts.

In this study, we investigate how inheritance laws are applied in practice and how such practices influence the updating of the land register. To achieve this, we zoom into the practices of inheritance to find out the particular aspects that have direct and indirect implications for Ghana’s current land registration practices.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we draw on research and theory in the domain of legal pluralism to understand how inheritance practices are situated within Africa’s legal plurality. In Section 3, we describe the geographic context and methods. In Section 4, we describe the three main practices of inheritance in Ghana highlighting their spiritual and cultural meanings and identify the types of property that emerge from the inheritance practices. In Section 5, we discuss the implications of inheritance practices for Ghana’s current land registration and draw more general conclusions in Section 6.

2. Plurality of Inheritance Laws

Inheritance is influenced by multiple laws deriving from both statutory and non-statutory sources. These laws define the manner of transfer, heir eligibility, associated rights, responsibilities and restrictions [26]. However, the plurality in the laws of inheritance reflects on the relative strengths of the state [19,27]. Where there is a strong state capacity, inheritance is often regulated by state law, as in the case of some western European countries. However, when state capacity is relatively weaker, different sets of laws regulate inheritance concurrently, affording people the opportunity to orient themselves to preferred laws or a combination thereof [1,19,20]. These concurrent laws often apply in contradictory ways, thereby leaving much interpretative and negotiating space in the outcomes of inheritance [5].

In most parts of the global south, including Africa, existing political landscapes are often characterized by weak state capacity and reflect combinations of different forms of hybrid governance [27]. In Africa, this plurality of laws derives historically from the interaction between African customs and those of the colonial administration [20]. Although with significant heterogeneity, pre-colonial Africa had its rules and norms commonly termed as customary or indigenous laws by the colonial and subsequent independent governments [28] which regulated human behaviour and social interactions including inheritance at different levels of social organisations; the family, clan, community and kingdom. With the advent of colonialism, additional legal systems were introduced by the colonial administration which they considered superior to native rules and norms (which they considered primitive) [29]. Religious and spiritual belief systems, which existed in Africa long before colonization; and before the introduction of monotheistic religions through colonization [30], still play an important role in the lives of many people. The work of Evans [31] on plural inheritance orders in Senegal demonstrates tensions that emerge from the contradictory terrains of law (the statutory family Code), custom and religion (especially Islam) and how such tensions reflect on the overall governance of inheritance and state capacity. Evans shows that different inheritance laws have points of convergence and divergence but how and where each is applied depends more or less on location (rural vs urban), ethnic group or religion. Similarly, Sodiq [32] explains the ambivalence of the Yoruba Muslims of Nigeria in the choice of inheritance laws. He noted that Yoruba Muslims tend to opt for whatever benefits them from Islamic law, Yoruba customary law or statutory law respectively.

In sum, the plural configuration of law in Africa which orders society, including inheritance, derives from three sources which in themselves are heterogenous: (a) the indigenous African customs termed as customary law (b) statutory laws which evolved from the colonial heritage of western legal systems into Africa and (c) the incursion of world religions into Africa through trade and colonialism [33]. Across Africa and other parts of the world, these three sets of laws run in parallel and co-exist at different scales of superiority and subordination [34].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Sites

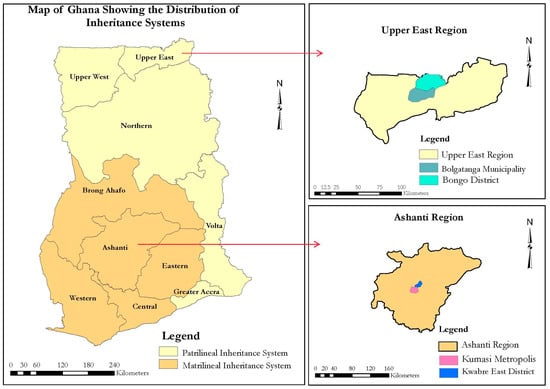

This study is conducted in two regions of Ghana that exhibit classic examples of matrilineal and patrilineal inheritance practices namely, Ashanti and Upper East regions respectively. At the same time, these regions fall under different land governance structures. The Ashanti region has a centralized land governance whereby chiefs hold land in trust and on behalf of their subjects (community members). They exercise political authority and fiduciary control over land. The Upper East region is decentralized and land control devolves from earth priests to clans and families. Historically, chiefs in the Upper East region have had political authority over land while the earth priest performs spiritual (religious) functions over land in terms of allocations, use and transfers [35]. Within each region we selected one urban and one rural district in order to observe the changing forms of inheritance laws as they manifest in different practices. In the Upper East region, we selected Bolgatanga (Urban) and Bongo (rural). In the Ashanti region we selected Kumasi (urban) and Kwabre East (rural). The study areas are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of Study Areas.

3.2. Data Sources

We use both primary and secondary data in this research. The primary data was collected through focus group discussions, semi-structured and in-depth interviews between May 2017 and August 2018. The focus group discussions consisted of 8 to 10 participants including family heads, earth priests, community elders and successors of inherited property (both male and female). We asked participants questions on the general practices of inheritance. Specifically, these questions relate to the processes of inheritance transfers, the people who are qualified to receive inheritance and the responsibilities associated with inheriting property (both spiritual and economic). Through this, we gathered information on the general rules on inheritance both according to the customs and the actual practices as they take place in the communities. In total, 13 focus group discussions were organized; 9 in villages found within the two rural districts and 4 in the urban districts. We also conducted semi-structured interviews in order to solicit information from individual heirs on the processes they followed during inheritance, what they actually inherited and why they follow a particular inheritance law(s). They were conducted in all the 13 communities which gave us insights at the individual level and enabled us to crosscheck some of the responses from the focus group discussions especially in relation to the real practices. In total, 72 were conducted; 46 from rural areas and 26 from the urban areas. In addition to the semi-structured interviews, we conducted in-depth interviews with heirs and prospective heirs in order to draw detail insights from their individual accounts of how inheritance actually took place or was planned to take place. Through the interviews we gained insights into the differences in sharing property and associated constraints in terms of property holding. To understand the influence of religion on inheritance regulation, we asked respondents about their religious affiliations and how that affected their practices of inheritance. In addition, and to get a more rudimentary understanding on the religious regulation of inheritance, we interviewed clerics from the predominant religious faiths namely; Islam, Christianity and African Traditional religion. For the in-depth interviews, 12 were conducted across the urban and rural areas. Interview respondents were identified first through the help of Assemblymen (community representatives of the District Assembly) and then followed by snowball sampling.

The study also draws on secondary data including the Intestate Succession Law, 1985 (PNDC Law 111) and the Ascertainment of Customary Law Series (2009 to 2011) compiled by National House of Chiefs and Law Reform Commission, Ghana.

3.3. Data Analyses

For the analysis across data sources, we describe the practices of inheritance and the associated socio-cultural meanings based on the narratives gathered from the focus group discussions and interviews. We then used conventional content analysis to synthesize [36] the responses from interviews and focus group discussions to identify and sort the emerging types of property. In a next step, we discuss how the chronology of events leading to the sharing of property in themselves cast a time lag on the prompt reporting of land transfers for formal recording. Then, we evaluate how the emerging types of property align with the types of property rights that are practically registrable at the Lands Commission. Finally, we look at the logics on inherited property from the part of successors and that of the state’s recording system to see how such logics relate and influence the registration processes.

4. Results

In this section, we first describe how each inheritance law is applied in practice including the spiritual and cultural beliefs that are associated with them. Second, we identify the types of property that the different practices produce. This focus is segmented along matrilineal and patrilineal practices as reflected in the customs of the study areas.

4.1. Plurality in Ghana’s Inheritance Laws

Inheritance in the study areas and Ghana as a whole is regulated by statutory, customary and religious laws. Whereas the statutory laws are supposed to apply nationally, that of the customary and religious laws apply differently across communities and religious groups respectively. The statutory regulations on inheritance in Ghana are the Wills Act of 1971 (Act 360) and the Intestate Succession Law of 1985 (PNDCL 111) for testamentary and intestate disposition respectively. Customary laws on inheritance in the study areas take two forms namely, patrilineal and matrilineal inheritance. Religious laws on inheritance vary by the faith of religious groups and their written or oral doctrines. Religious laws are not confined to particular communities but cut across communities. In the following sections we describe how these three sets of laws are carried out in practice.

4.1.1. Customary Inheritance Practices

Customary practices of inheritance differ across the study areas. While patrilineal inheritance is practiced in the Upper East region (Bolgatanga and Bongo), matrilineal inheritance is practiced in the Ashanti region (Kumasi and Kwabre East).

• Patrilineal inheritance practices

In the Upper East region, the general practice is that property devolves from father to son or brothers in the absence of sons. According to the interviewed successors, it takes about a year or two to organize the funeral rites. After the funeral, land is shared among the sons either equally or according to seniority. However, depending on the disposition of the deceased’s patrilineage, especially when most of the successors are minors, the eldest successor holds and manages the property in trust for the other successors. In an interview, a successor holding property on behalf of the others says:

“….In this region, some people like to divide property..… But for us, we are not like that, the senior holds the property on behalf of the family. My grandfather built the house and gave it to my father, then to my senior brother and to me now. Everything in the house belongs to everybody, we have a cordial relationship among ourselves, we don’t fight over property.…”(Interview in Bolgatanga: 2018)

Females are deemed non-members of the patrilineage during property inheritance. So, they are given only use rights during inheritance. For example, in rural Bongo, where farmland is often the subject matter of inheritance, an unmarried adult daughter can farm on her late father’s land or stay in his house until she gets married. Even when there are no male successors, one of the daughters is required to stay at home to deliver a male child without marriage. Such a child is then considered as the successor. In both Bolgatanga municipality and rural Bongo district, when a daughter gets married, she is deemed to be part of her husband’s lineage. By this custom, daughters are excluded from all paternal property upon marriage. Similarly, widows also have only use rights in the property of the late husband without rights of appropriation and disposition, because they are members of a different lineage and would be considered a threat to the ability of the husband’s lineage to protect their lineal land. Widows can build and farm on the land but they can neither sell nor transfer it. Thus, the ownership rights of females to property are always embedded in a male connection; either son or husband.

Inheritance in the Upper East Region also takes place beyond the conjugal family and patrilineage. At the clan and community levels, heads of clans and earth priests in Bolgatanga and Bongo exercise fiduciary rights over sacred lands. These are undeveloped lands, which are used for farming by clan heads for burial and spiritual purposes (for example shrines). Heads of clans and earth priests of communities inherit these type of lands from their predecessors for a lifetime and it is a taboo for them to engage in any form of self-appropriation with respect to these lands.

At both the micro level of individual successors and the macro level of clans and communities, land inheritance carries certain meanings among the Frafra people who are the dominant tribe in Bolgatanga and Bongo. The transfer of land by inheritance marks distinct purposes of livelihood, spirituality and immortalization. In rural Bongo, land is the most important factor of production as it provides the basis for farming and livelihood. But even then, the productive capacity of land in farming is linked to the grace of the gods, to whom sacrifices are made at the beginning of the farming season for bumper harvest and to whom thanks is given after harvest (interview with earth priest in Bolgatanga: 2018). Thus, the transfer of land denotes the reception of spiritual responsibility. Within the patrilineage, members make figures of their ancestors, hence, to inherit the land is to inherit the responsibility of pacifying the ancestors. According to a family head in Bolgatanga, inheriting certain types of land requires the performance of spiritual actions, as for the land in front of the family house, which is considered the site of ancestral roots (called “Dabozuo”). The connection between land and spirituality at the clan and community levels is reflected in the title of the overall custodian of land, the “earth priest,” who is in charge of the gods, manages shrines, sacred groves and also sanctifies land allocations and transfers. Moreover, the fact that land inheritance in Bongo and Bolgatanga takes place patrilineally between fathers and son(s) or brothers means that inheritance processes define lineage membership and genealogy. Therefore, land inheritance does not only constitute a transfer of physical land for livelihood, it also marks the transfer of cultural heritage and spiritual identity. In this sense, inheritance creates and maintains one’s identity and genealogy through one’s connection to land through time.

This connection between property and genealogy is also present for developed property. Developed property, such as houses in Bongo and Bolgatanga, are occupied or rented out (mostly in Bolgatanga) by successors. Either way, successors refer to the property in the name of the ancestor who built it. This is regarded as giving honour to the ancestor and by so doing they immortalize his name. Regarding this, a respondent in Bolgatanga said:

“...When discussing matters of this house, we refer to my grandfather (the one who built it) a lot. We appreciate what he has done for us. Attaching his name to the property is an honour and for me, if there is a chance to even build a statue of him in front of the house I will like to do that.….”(interview in Bolgatanga: 2018)

Additionally, in urban Bolgatanga, the economic exploitation of property positions property inheritance as a transfer of economic power between father and son(s).

• Matrilineal inheritance practices

In the Ashanti region, property devolves matrilineally through female lines. Females and their children are considered to be permanent members of the lineage with respect to property. The children of male lineage members are considered non-members. Thus, property devolves from maternal uncles to nephews and from mothers to daughters. The property of a man devolves to his sister’s children while his children inherit from their maternal uncle. The sharing of the deceased’s estate takes place after the funeral rites on the 40th day after death. Under matrilineal inheritance systems, a distinction is always made between self-acquired property and lineage property. Self-acquired property can be given as a gift or through a will (written or oral) by the holder. But if he dies intestate, it becomes lineage property; and the lineage head decides on which of the nephews will succeed. For maternal property, the custom allows male children only a lifetime use right without any rights of appropriation and disposition.

Like Bolgatanga and Bongo, property inheritance in Kumasi and Kwabre East define lineage membership and genealogy. An important aspect of matrilineal inheritance is that the intestate estate of a deceased lineage member is considered as lineage property. The head of the lineage then appoints a successor to manage the estate on behalf of the lineage. In Kwabre East, such lineage property if farmland, is farmed by the appointed successor with the responsibility to take care of the deceased’s conjugal family and lineage members in general. In this context, succession of lineage property denotes leadership and control. By virtue of the elevated position of lineage property succession, nephews of a deceased male lineage member struggle among themselves and also lobby with lineage elders for appointment as successor. In Kumasi metropolis like Bolgatanga, successors of inherited property derive economic benefits such as renting of houses. Additionally, the immortalization of deceased’s name was found to exist in both Kumasi and Kwabre East for the same reasons of giving honour to the deceased as found in Bolgatanga and Bongo. Although the Akans have beliefs in the spirits of the earth, called “Asase Yaa,” the dimension of spirituality in land inheritance was found to be less influential in Kumasi and Kwabre East in comparison to Bolgatanga and Bongo.

In sum, inheritance in the context of the study areas denotes more than a mere transfer of land/property from one person to another or from one group to another. It also, defines lineage membership, genealogy and identity through time. The example of the naming convention above is especially illustrative, where the property in question remains named after the original ancestor as it passes from generation to generation of subsequent names. In this way the transfer of land and developed property through inheritance establishes a diverse array of relations between people and space across the spectrum of economic, social and spiritual dimensions in time. These relations coexist at varying levels of dominance and subordination according to situations and contexts.

4.1.2. Religious inheritance practices

Three religions are practiced in the study area in varying forms. These are Christianity, Islam and Traditional African religion. The Traditional African religion has local origins and predates Christianity and Islam, which have foreign origins. Thus, the practices of the Traditional African religion evolved over time and are rooted in almost every endeavour of the lives of people including inheritance and are often regarded as the custom. For example, in the Upper East region, families have figures of their ancestors (called “Bagre”) which they serve, while the earth priest functions as a traditional spiritual leader in pacifying the gods and pouring libation during land transfer, dispute settlement and farming. The practices of the polytheistic Traditional African religions are closely tied into everyday lives in West Africa. They originate in pre-colonial spiritual believes that formed in close association with the needs of West African settlers, especially the fertility of land and women [37]. The most important higher powers in traditional religion are ancestors and natural spirits, especially associated with the forest and earth [37] indicating the traditionally close association between land and spirituality. As Christianity and Islam are becoming more dominant, the practices of Traditional African religion are increasingly referred to as customary practices. The meeting of monotheistic world religions and indigenous spiritual believe systems has been characterized by a relatively eclectic and pragmatic mingling between believe systems and associated norms and practices [37]. For example, Muslim respondents in Bongo follow the customary practices of inheritance although they do not ascribe to the beliefs of the Traditional African religion. Thus, the customary practices of inheritance described in the previous section also reflect the practices of Traditional African religion.

Of the monotheistic beliefs, Christianity does not have strict religious codes that direct the distribution of inheritance. Interviews with some Christian heirs in Bolgatanga and Bongo revealed that they observe the customary practices of inheritance as there are no binding Christian directives to that effect. In the case of Kumasi and Kwabre East, Christians give priority to a mix of the Intestate Succession Law and customary law for the same reason as found in Bolgatanga and Bongo. To gain more understanding in this regard, we interviewed a Christian cleric in Bolgatanga, who said that:

“….there are no exact rules on how to share inheritance. As a religious body, we only complain when we see that there is injustice in the sharing of inheritance. But mostly, people don’t consult us on issues of inheritance, they only invite us for the funeral and burial of the deceased”.(Interview in Bolgatanga: 2017)

Islam however has a coded law pertaining to inheritance that is generally known by Muslims especially in urban areas. We found that Muslims in urban and rural areas do not evenly implement the Islamic inheritance rules. For example, in Bongo, Muslims follow the customary practices of inheritance without recourse to the Islamic law. Conversely, in Bolgatanga, we found that Muslims gave priority to Islamic practices of inheritance. In the case of Kumasi and Kwabre East, Muslims across rural and urban areas gave priority to Islamic inheritance law.

According to Islamic inheritance, a male successor takes twice the share of a female. It provides for the surviving spouse, parents and siblings (Qur’an 4:11–12) in varying shares depending on the availability of other beneficiaries. According to a Muslim cleric in Bolgatanga, Islamic inheritance prescribes that the estate of a deceased can only be shared after the settlement of his/her debts. Islamic practices require that the debts and promised gifts of the deceased be settled followed by the performance of the funeral rites before the remaining property is shared. Whereas the burial is done soon after death, the funeral rites take place from the following day but the debt might be settled sooner or later depending on the family and the amount of debt. We found that the practical implementation of Islamic inheritance takes forms that fit the local context and situations instead of the prescribed form. For example, in a particular case in Bolgatanga, due to limited space within an inherited house, the proportion of shares between male and females could not be maintained. Unmarried female and young male successors were made to share a space with their mothers so as to provide space for the elderly males who had their conjugal families in the house (Interview with a Muslim respondent in Bolgatanga: 2017). Also, we found in the case of both Kumasi and Bolgatanga that, even when the deceased leaves behind many houses, successors are not given full houses, instead, they are given different spaces (rooms) in different houses. The rationale for this is to keep them together to enhance the unity among the deceased’s children.

In sum, the different practices of inheritance among other things have different timings for the sequence of events leading to the sharing of inherited property (see Table 1). In both patrilineal and matrilineal areas, it is required that property be shared only after the performance of the deceased’s funeral. As shown in the Akan matrilineal communities, property is shared on the 40th day after death. In the Frafra patrilineal communities, sharing of property takes place after the funeral which takes about one or two years on average but could take longer. Islamic inheritance requires the performance of the funeral, settlement of the deceased’s debt and/or bequests before sharing of property and this may happen immediately or take longer to settle. The Intestate succession law is silent on the timing of sharing and the prerequisites before sharing. The timing and prerequisites affect how soon changes in landholding status can be reported. These are summarized on Table 1.

Table 1.

Time effect of inheritance practices on the reporting of changes in landholding status.

In a simplified model, the practices of inheritance described above apply to people in layers where the statutory is supposed to apply to people nationwide, the customary in specific communities and tribes and the religious according to membership in given religious faith. However, in most cases, more than one set of practices apply to an individual or even groups. These different multi-layer constellations allow room for choice making by heirs which creates interactions between different inheritance practices by which they shape one another and also compete for patronage. We discuss these interactions in the following section.

4.1.3. The Mingling of Statutory with Customary and Religious Practices

Prior to the passing of the current statutes, inheritance was regulated by marriage laws namely, the Marriage Ordinance of 1884 (CAP 127) and the Marriage of Mohammedans Ordinance 1907 (CAP 129). These laws were applicable to cases where the marriage was registered. Where the marriage was not registered, the customary laws took precedence. Due to the poor mechanisms of distributing property in the earlier laws and customary law, the Will’s Act of 1971 (Act 360) and the Intestate Succession Law, 1985 (PNDCL 111) were enacted to regulate testamentary and intestate succession respectively. However, during interviews and focus group discussions in the study areas, we found that written wills do not play any significant role in inheritance, rendering the Will’s Act relatively unimportant in practice. The Intestate Succession Law on the other hand has a prescribed scheme of property sharing and is applicable to most cases of inheritance in the study areas. Nonetheless, it is not implemented to the letter but mostly adapted in ways that fit local exigencies. The law constantly interacts with pre-existing customary and religious practices in varying degrees across rural and urban contexts. It has little influence on Islamic and patrilineal inheritance practices compared to the matrilineal practices. This is because the law implies the transmission of property from deceased parents to their direct children and surviving spouses which aligns more closely with the practices of patrilineality and Islam. In Kumasi and Kwabre East, the law implies a change in social structure of the matrilineage, because in these areas applying the law in practice means that property has to move from parents to children and spouse instead of nephews. Through the activities of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and gender rights activists on the mass media, conjugal families in matrilineal communities are increasingly becoming aware of the opportunities presented by the Intestate Succession Law as opposed to the disadvantages posed by the matrilineal practices. Such awareness strengthens the rights of the conjugal family of the deceased, and at the same time weakens the hitherto claim making powers of the matrilineage, which now take the form of negotiation and lobbying. In an interview, a successor praises the changes made by the Intestate Succession Law when she says:

“…The matrilineage has a share of inheritance but if the deceased was married, they can’t just go and take everything like they used to do and leave the children and the widow like that, no. Now they give some (inherited property) to the widow and especially the children. The matrilineage gets a small portion.”(Interview in Kumasi: 2018)

Although people do not follow the Intestate Succession Law very strictly to the letter, the overall effect of it has guided the behaviour of the lineage members and nephews from overpowering the conjugal family of the deceased. The conjugal family on the other hand explores ways to allocate a reasonable proportion to the matrilineage for fear of spiritual attacks and physical abuse. Thus, the application of the law is highly contextual and illustrates the shifting powers and tensions between the conjugal family of the deceased and his/her matrilineage. A widow in the Kumasi metropolis says:

“…You can follow the law and keep a large share of the property but you may not live to enjoy it peacefully. If the matrilineage is not happy with you, they can attack you spiritually and you and the children may die”(Interview in Kumasi: 2017)

In sum, the different set of laws in themselves and how they manifest in practice have variations in terms of their interactions across the study areas. In the Upper East region, customary practices of inheritance dominate in rural areas but compete with Islamic inheritance practices among Muslims of the Frafra ethnic group in urban areas, sometimes leading to a mixture of the two. Statutory practices of inheritance do not play any important role in both rural and urban areas in the Upper East. Thus, the only “space” for competition and interaction among inheritance practices in the Upper East is the urban context where Islamic and customary practices interact and compete. Across rural and urban areas in the Ashanti region, the three inheritance practices interact and compete but the nature of the competition is highly idiosyncratic and depends more on a combination of an individual’s religious affiliation and ethnic belonging. For example, customary practices of inheritance compete with both Islamic and statutory inheritance practices especially for Muslims who also belong to the Akan ethnic group. In this case all three practices apply to them. For non-Muslims, only customary and statutory practices compete and apply to them during inheritance. Unlike the Upper East region, the pronounced intermingling and competition between statutory and customary inheritance practices in the Ashanti region illustrates the tensions that emerge from the changes in social structure sought by statutory inheritance practices. The customary and statutory practices of inheritance sought to empower different groups of beneficiaries (i.e., heirs/conjugal family vs. the matrilineage) which provides room for forum shopping by successors but also fuels tensions between the two social units.

The different practices of inheritance described above result in various types of property. In the following section we have sorted these into four types of property.

4.2. Emerging Types of Property Across Different Inheritance Practices

The three inheritance practices and their combinations outlined in Section 4.1 produce various types of property namely, joint property (within the conjugal and extended family), individual property and secondary property (see Table 2 below). In the following section, we analyse the different types of property that emerge.

Table 2.

Emerging types of property from different inheritance practices.

4.2.1. Joint Property of the Extended Family

As shown in the matrilineal practices of Kumasi and Kwabre East, the intestate estate of a deceased devolves partly to his conjugal family and partly to the matrilineage. The part that devolves to the matrilineage whether developed or undeveloped land becomes a group property, jointly owned by all lineage members but is managed by an appointed successor. This means that any member of the lineage is capable of benefitting from such a property. For example, they can live in it if it is a residential property without fixed shares and claims. Upon the death of a member, his/her rights devolve to the surviving members. The appointed successor oversees the allocation of space within the property, undertakes maintenance and also manages the returns if the property is income generating. This type of property can be likened to a joint tenancy because there is a right of survivorship but in this case, the tenancy is not created by a legal instrument and also a member cannot dispose any part of the property.

4.2.2. Joint Property of the Conjugal Family

In Kumasi and Kwabre East, the mix of statutory and matrilineal practices result in a situation where the conjugal family of the deceased and the matrilineage devise suitable ways of sharing the intestate property of the deceased. By virtue of the statutory backing, the matrilineage often allows the conjugal family to retain the house where they once lived with the deceased. The conjugal family holds such a property jointly as tenants in common according to the statutory inheritance practice. Also, under patrilineal practices, joint property is created when the eldest successor holds the inherited land on behalf of the other successors who are minors. Similarly, from Islamic inheritance practices in both Ashanti and Upper East regions, the allocation of space (rooms) to children (successors) across different buildings belonging to the deceased creates joint property among the conjugal family of the deceased. They can deal privately with their respective spaces. This type of property can be likened to tenancy in common since there is no right of survivorship following the death of a member especially for the statutory and Islamic inheritance practices.

4.2.3. Individual Property

Individual property rights are mostly created through patrilineal inheritance practices. For example, the distribution of a late father’s land among male successors in Bongo results in individual shares which are held and used as individual property. This type of property allows holders to exercise unilateral rights of disposition and use. Matrilineal inheritance scarcely produces individual property, because by custom the intestate property of the deceased belongs to the matrilineage. Even when matrilineal practices are mixed with statutory practices, it results in group ownership by the conjugal family if the deceased left behind one house. However, when the deceased leaves behind many houses, the mix of statutory and matrilineal practices might also create individual property.

4.2.4. Secondary Property

Under matrilineal inheritance, males have only use rights in the intestate estate of a deceased mother compared to their sisters who have ownership rights in the property. Similarly, females under patrilineal inheritance practices have secondary rights over the intestate estate of the father. Another category of secondary rights is headship property (land) held by earth priests and family heads in Bolgatanga and Bongo. By custom, they have the right to use such property for only a lifetime and in delineated ways only.

In sum, the different inheritance practices create a variety of property which define the scope of holders, use and disposition. Whereas patrilineal inheritance practices tend to create more of individual property, matrilineal and Islamic inheritance practices create more of group property and statutory practices create both individual and group property depending on the number of houses (property) the deceased left behind. From the perspective of land rights documentation, each type of property has different implications for registration. In the following section, we discuss these implications.

5. Discussion

Implications of Inheritance Practices for Current Land Registration

Our analysis reveals three sets of influences that inheritance practices have on land rights reporting and recording in the context of Ghana namely; (1) the timing of reporting transfers, (2) the production of complex forms of property and (3) conflicting logics between existing property holding notions and land registration.

Firstly, the timely reporting of property transfers is essential to keep the land register reflective of reality [38]. Earlier in 1995, Binns and Dale [39] already highlight this connection and argued that the success or failure of the land registration system depends on how prompt property transactions are reported for recording. Further, Binns and Dale [39] argued that in countries where the customs of inheritance absolutely prescribe succession to landed property, property will frequently change hands without any form of formal documentation. Both arguments put forth by Binns and Dale, hold to greater extents in the context of Ghana’s land registration and inheritance landscape. Inheritance laws in Ghana exhibit certain characteristics that influence when the reporting of inheritance transfers could take place. For example, the time it takes to perform funeral rites and other prerequisites such as the payment of the deceased’s debts dictate when property can possibly be registered (shown earlier on Table 1).

Secondly, inheritance practices produce complex forms of property which call for more flexibility in the way property is recognized and registered. As shown in Table 2, the emerging types of property are categorised into communal and individual property rights. Of the two categories, only individual property rights are practically registered by the Ghana Lands Commission as leaseholds in the study areas [40]. Other types of property that are communal in nature (such as the joint property within the extended family and the conjugal family and secondary property) fall outside the domain of practically registrable rights within the Ghana Lands Commission (see Table 3 below). Since the Intestate Succession Law does not apply to joint property held by the matrilineage, such property hardly reverts to individual property in which case it could get registered [41]. Property of the matrilineage has a host of unspecified transitory beneficiaries which further complicates the specificity that is required for recording into the land register. As a result, such property accumulates over time and is transferred from one generation to the other without any formal record of transfer [16,41]. The only time when a property of the matrilineage is recorded in the land register is when the original holder already registers it before death. Even then, updating seldom takes place after the inheritance transfer which renders the hitherto updated record out of date. However, it is important to mention that, the increasing competition over land and the creeping marketization of property may in effect break down this type of common property in the longer run [42]. Although the emergent types of property that are communal in nature tend to provide a safety-net for lineage members [43], there is a misalignment between them and the formal systems of registration (see Table 3). This explains in part why less property is registered in Ghana and Sub-Saharan Africa where inheritance is the most common source of property acquisition [2,3]. The relationships between the produced types of property and the current land registration system are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationships between different types of property and the current system of land registration.

Thirdly, some of the notions that inherently surround the transfer of property by inheritance do not match the logics of property registration. As demonstrated for the study areas, inheritance has spiritual connotations and is at the same time a process of honouring the dead (immortalization). For example, in the case of the latter, inherited property if registered, would remain in the name of the original ancestor in the land register as it passes from generation to generation of subsequent names. In such a situation, the registration itself is perceived as a mere definition of the boundaries of the property but not as benefiting whoever is named as the titleholder to the exclusion of other recognized lineal members [25]. Kingwill [23] in her study of family lands in South Africa highlights how families intuitively prefer for an ancestor’s name on the land title as a strategy to prevent living family members from having too much power on property. Although these strategies may work to support certain social logics, their effects on land information are the reverse of what the processes of updating the land register sought to achieve. They keep the land register out of date as it ceases to reflect the reality of property holdings and this weakens its capacity to support tenure security and land markets [8,38]. In the processes of land registration, property mostly remains while the names of subsequent holders change upon every instance of transfer. This is the process through which the land register is kept up-to-date as shown in the dynamic model of land registration [38] (p. 108).

6. Conclusions

The need to keep the land register up-to-date is triggered by land transfers which take place in different forms including sales, inheritance, gifts, mortgages and compulsory acquisition. Up-to-date land information can support land market activities and also enables landholders to claim their rights legally against other people and even against government for compensation during compulsory acquisition. In contexts with active land markets the need to update the land register is often triggered by sale transactions and inheritance in contexts with relatively dormant markets [38]. The global south is characterized by relatively less active land markets where inheritance is the most common means of land acquisition and is also governed by plural laws.

In the context of Ghana, different laws influence inheritance practices and also interact with one another to produce different types of property and property relations. These interactions take different forms and exhibit regional variations across Ghana and highlight the relative importance that statutory and religious laws have come to play in contexts where customary laws pre-existed and directed the choices made by individuals and groups of people in the structuring of social units and livelihoods. The types of property that are produced through inheritance practices are diverse and evolve depending on how inheritance laws interact, and also how people resort to different blends of practices. As Rose [1] observed in her study of inheritance in Southern and Eastern Africa, inheritance practices may be based less on specific laws than on people’s judgement of what is right. Since inheritance laws do not map to people only on one-to-one basis but could also be many-to-one (where more than two laws apply to a particular person/people), possibilities of having blends are high. Hence, there is no fixed typology of types of property or no uniform set of inheritance laws across Ghana, instead, there exist different blends of property and modified forms of laws in practice. This makes both need and possibility to register inherited property in many cases low. If we do make an attempt at simplifying the interplays of laws to the main types of property that they produce we see that they imply different timings for possible registration and that some types of property like individual property lend themselves to registration more while others do not. The connections between plural inheritance practices and the land register are not only found in Ghana’s context of property inheritance but are generally characteristic of Africa, where inherited colonial legal systems are thrust upon ongoing social arrangements in which there are complexes of binding obligations already in existence [20]. In many regions, including outside of Africa with weak state capacity, non-state laws and hybrid forms of governance are relatively durable [27].

The biggest challenge for full-fledged, uniform registration remains therefore; either to make a move from communal to individual rights registration or to incorporate sufficient flexibility into the current recording systems for the registration of communal rights as much as current technology can support. On the one hand, the push for individual property will call for the necessity of at least partially transforming the value of land and buildings from a means to structure social relationships through time into a physical asset, the value of which would mostly be expressed in monetary terms and which can be mobilized across existing social units by means of a recording system. That is to say, for the diversity of customary land rights to be assimilated into an administrative grid, it necessarily entails some form of transformation into a convenient shorthand [44] (p. 24). In other words, it would require for land to take on a different meaning than it currently has in many parts of the country, although not exclusively. It is likely that this process takes place first and foremost in urban and peri-urban areas, where the ties between social unit structure and land/buildings is already broken through migration, where new inheritance practices and related types of property emerge due to a mixing of people from different social groups in combination with a stronger statutory legal influence and influence of actors from outside of domestic markets; and where therefore financial markets around individual property begin to dominate. On the other hand, the development of sustainable recording systems as formal schemes of legibility making would be untenable if they do not incorporate some elements of the very complexity (diversity) they intend to simplify or dismiss [44] (p. 7). In the domain of land administration, land relations are modelled in the form of subject—rights, restrictions, responsibilities (RRR)—object [38,45,46] and keeping the land register useful in time and space requires the updating of these relationships [38] (p. 18). What if the reality to be captured in a land register does not present itself in the model: subject—rights, restrictions, responsibilities—object; but multiple subjects with different rights, restrictions and responsibilities connected to an object? This calls for flexibility in the manner in which land rights are recorded which could enable at least the partial capture of communal land rights including inheritance which are more pronounced in rural areas which cover much of Ghana’s land area and Africa more generally. In these areas, the ties between social structure and property are still strong and the interpretation of property goes beyond the physical asset, requiring some form of recording that will at least partially capture these complexities than is currently the situation at present. For example, in relation to the immortalization of ancestors name, property rights could be recorded in layers; the name of the broader landholding social unit (name of ancestor, extended or conjugal family), the name of the current trustee(s) (the family member holding the property in trust for the others) and the RRR at each level. Such a layered recording format has the potentials of keeping a balance between cultural values whilst at the same time meeting the administrative need to record. Similarly, in regards to the sharing of rooms for successors in different houses belonging to the deceased, emerging technologies such as 3D cadastres could be deployed to capture such interwoven property rights [47]. However, despite the potentials of 3D cadastres, the technology and capacity to support it are not readily available in most developing countries.

In conclusion, the variations of needs for registration across urban, peri-urban and rural areas require flexibility in the way land rights are recorded. Attempts at developing uniform nation-wide recording systems should be fit-for-purpose by providing nation-wide frameworks that allow room for contextual variations that meet local needs. In these areas future research on the development of land registries and cadastres might therefore want to focus specifically on the role played by various state actors vis-à-vis private societal and international actors from bottom-up instead of the traditional top-down approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A., C.R. and J.Z.; methodology, Z.A.; formal analysis, Z.A.; investigation, Z.A.; writing—original draft, Z.A.; writing—review and editing, Z.A., C.R. and J.Z.; supervision, C.R. and J.Z.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pauline Peters for the initial review of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rose, L.L. Children’s Property and Inheritance Rights and Their Livelihoods: The Context of HIV and AIDS in Southern and East Africa; Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakari, Z.; van der Molen, P.; Bennett, R.M.; Kuusaana, E.D. Land consolidation, customary lands and Ghana’s Northern Savannah Ecological Zone: An evaluation of the possibilities and pitfalls. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiama, K.O.; Bennett, R.; Zevenbergen, J. Land Consolidation for Sub-Saharan Africa’s Customary Lands—The Need for Responsible Approaches. Am. J. Rural Dev. 2017, 5, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat Handling Land: Innovative Tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure; UNON, Publishing Services Section: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012; ISBN 9789211324389.

- Cooper, E. Inheritance Practices and the Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty in Africa: A Literature Review and Annotated Bibliography; CPRC Working Paper 116; Chronic Poverty Research Centre: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kameri-mbote, P.G. Gender Dimension of Law, Colonialism and Inheritance in East Africa: Kenyan Women’s Experiences. Verfass. Recht Übersee/Law Polit. Africa Asia Lat. Am. 2002, 35, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, D.; Stillwell, J.; See, L. A new methodology for measuring land fragmentation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 39, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, G.; Griffith-Charles, C. Assessing the formal land market and deformalization of property in St. Lucia. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, I.; Enemark, S.; Wallace, J.; Rajabifard, A. Land Administration for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; ESRI Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781589480414. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, K. “A Huge Problem in Plain Sight”: Untangling Heirs’ Property Rights in the American South, 2001–2017; Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Gaither, C.; Zarnoch, S.J. Unearthing ‘dead capital’: Heirs’ property prediction in two U.S. southern counties. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingwill, R. Papering over the cracks: An ethnography of land title in the Western Cape. Kronos 2014, 40, 241–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kalin, H.C. International Real Estate Handbook: Acquisition, Ownership and Sale of Real Estate Residence, Tax and Inheritance Law; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Szydlik, M. Inheritance and Inequality: Theoretical Reasoning and Empirical Evidence. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2004, 20, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingwill, R. An Inconvenient Truth: Land Title in Socisl Context. In Land Law and Governance: African Perpectives on Land Tenure and Title; Mostert, H., Verstappen, L., Zevenbergen, J., van Schalkwyk, L., Eds.; Juta & Company (PTY) Ltd.: Claremont, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tagoe, N.D.; Mantey, S.; Adjei, S.; Soakodan, M. The Role of the Land Surveyor in Land Acquisition and Compensation—A Case Study of the Tarkwa Mining Communities, Ghana. In Proceedings of the Territory, environment and cultural heritage, Rome, Italy, 6–10 May 2012; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Deere, C.D.; Doss, C.R. The gender asset gap: What do we know and why does it matter. Fem. Econ. 2006, 12, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takane, T. Customary Land Tenure, Inheritance Rules and Smallholder Farmers in Malawi. J. S. Afr. Stud. Cust. L. Tenure J. S. Afr. Stud. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2008, 34, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prill-Brett, J. Indigenous Land Rights and Legal Pluralism among Philippine Highlanders. Law Soc. Rev. 1994, 28, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.F. Law and social change: The semi-autonomous social field as an appropriate subject of study. Law Soc. Rev. 1973, 7, 719–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroula, G.S.; Thapa, G.B. Impacts and causes of land fragmentation and lessons learned from land consolidation in South Asia. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, G.B.; Niroula, G.S. Alternative options of land consolidation in the mountains of Nepal: An analysis based on stakeholders’ opinions. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingwill, R. Lost in translation: Family title in Fingo village, Grahamstown, Eastern Cape. Acta Juridica Plur. Dev. Stud. Access Prop. Afr. 2011, 2011, 210–237. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R. Gendered struggles over land: Shifting inheritance practices among the Serer in rural Senegal. Gend. Place Cult. 2016, 23, 1360–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.E. Revisiting the Social Bedrock of Kinship and Descent in the Anthropology of Africa. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Africa; Grinker, R.R., Lubkemann, S.C., Steiner, C.B., Gonçalves, E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, D.S. The Islamic inheritance system: A socio-historical approach. Arab Law Q. 1993, 8, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyntjens, F. Legal Pluralism and Hybrid Governance: Bridging Two Research Lines. Dev. Chang. 2015, 47, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allott, A.N. What is to be done with African customary law? The Experience of Problems and Reform in Anglophone Africa from 1950. J. Afr. Law 1984, 28, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, J.S. Inherited legal systems and effective rule of law: Africa and the colonial legacy. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2001, 39, 571–596. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, D. Law and Religion in Africa: Comparative Practices, Experiences and Prospects. Eccles. Law J. 2013, 15, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. Working with legal pluralism: Widowhood, property inheritance and poverty alleviation in urban Senegal. Gend. Dev. 2015, 23, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodiq, Y. An analysis of Yoruba and Islamic laws of inheritance. Muslim World 1996, 86, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndulo, M. African Customary Law, Customs and Women’s Rights. Indiana J. Glob. Leg. Stud. 2011, 18, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, M.O. Traditional governance and African customary law: Comparative observations from a Namibian perspective. In Human Rights and the Rule Law in Namibia; Horn, N., Bösl, A., Eds.; Macmillan-Namibia: Windhoek, Namibia, 2009; pp. 59–88. ISBN 978-99916-0-915-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. The past and space: On arguments in African land control. Africa 2013, 83, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliffe, J. African: The History of a Continent, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, J. Systems of Land Registration: Aspects and Effects; Netherlands Geodetic Commission: Delft, The Netherlands, 2002; ISBN 9061322774. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, B.O.; Dale, P.F. Cadastral Surveys and Records of Rights in Land: FAO Land Tenure Study 1; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakari, Z.; Richter, C.; Zevenbergen, J. Exploring the “implementation gap” in land registration: How it happens that Ghana’s official registry contains mainly leaseholds. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsoati, E.; Morck, R. Family Ties, Inheritance and Successful Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from Ghana; NBER Working Paper 18080; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A.; Payongayong, E.; Aidoo, J.B.; Otsuka, K. Women’s land rights in the transition to individualized ownership: Implications for tree-resource management in Western Ghana. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2001, 50, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owiredu, P.A. The Akan system of inheritance today and tomorrow. J. Afr. Aff. 1959, 58, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998; ISBN 0300070160. [Google Scholar]

- Whittal, J. A new conceptual model for the continuum of land rights. S. Afr. J. Geomat. 2014, 3, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Todorovski, D.; Potel, J. Exploring the nexus between displacement and land administration: The case of Rwanda. Land 2019, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.; Rajabifard, A.; Stoter, J.; Kalantari, M. Legal barriers to 3D cadastre implementation: What is the issue? Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).