The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Authentic Followership, Positive Psychological Capital, and Project Performance: Testing for the Mediation Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

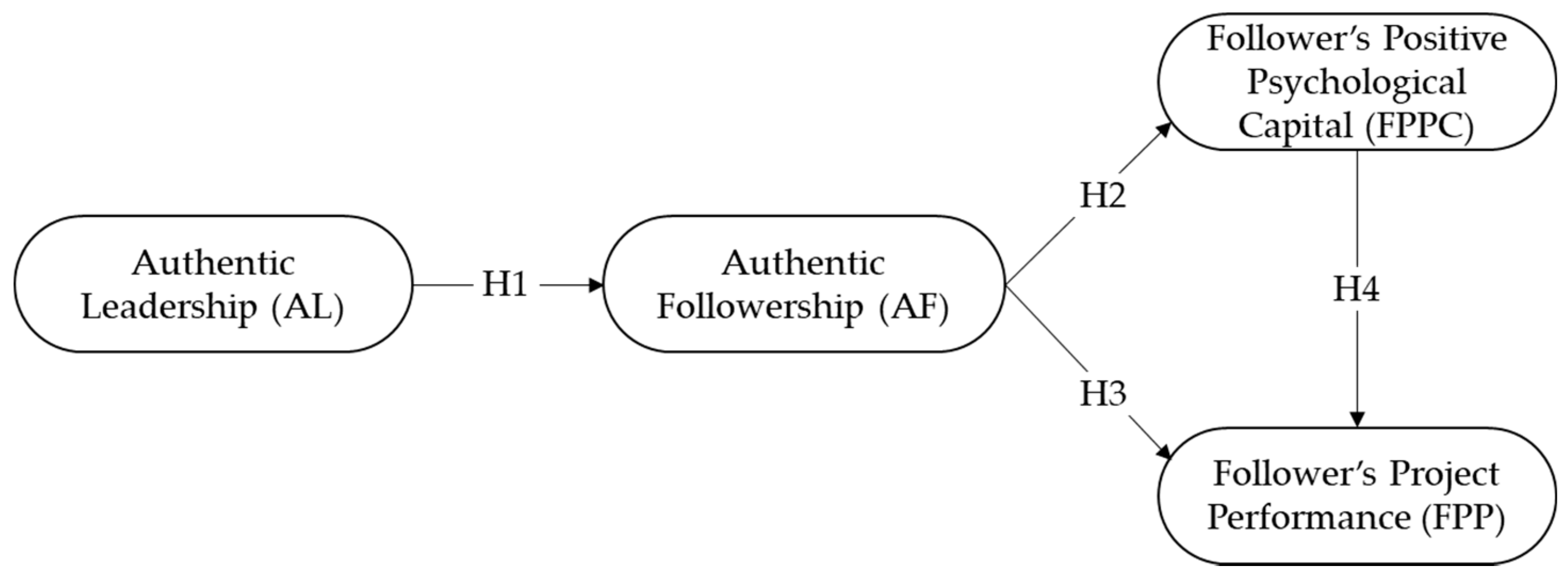

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Sustainability in Leadership for Education

2.2. Reviews on AL and AF

2.3. The Positive Relation between AL and AF

2.4. The Effect of AF on FPPC and FPP

2.5. The Positive Relation between FPPC and FPP

3. Methodology

3.1. Variables

3.2. Samples

3.3. Analysis Methods

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

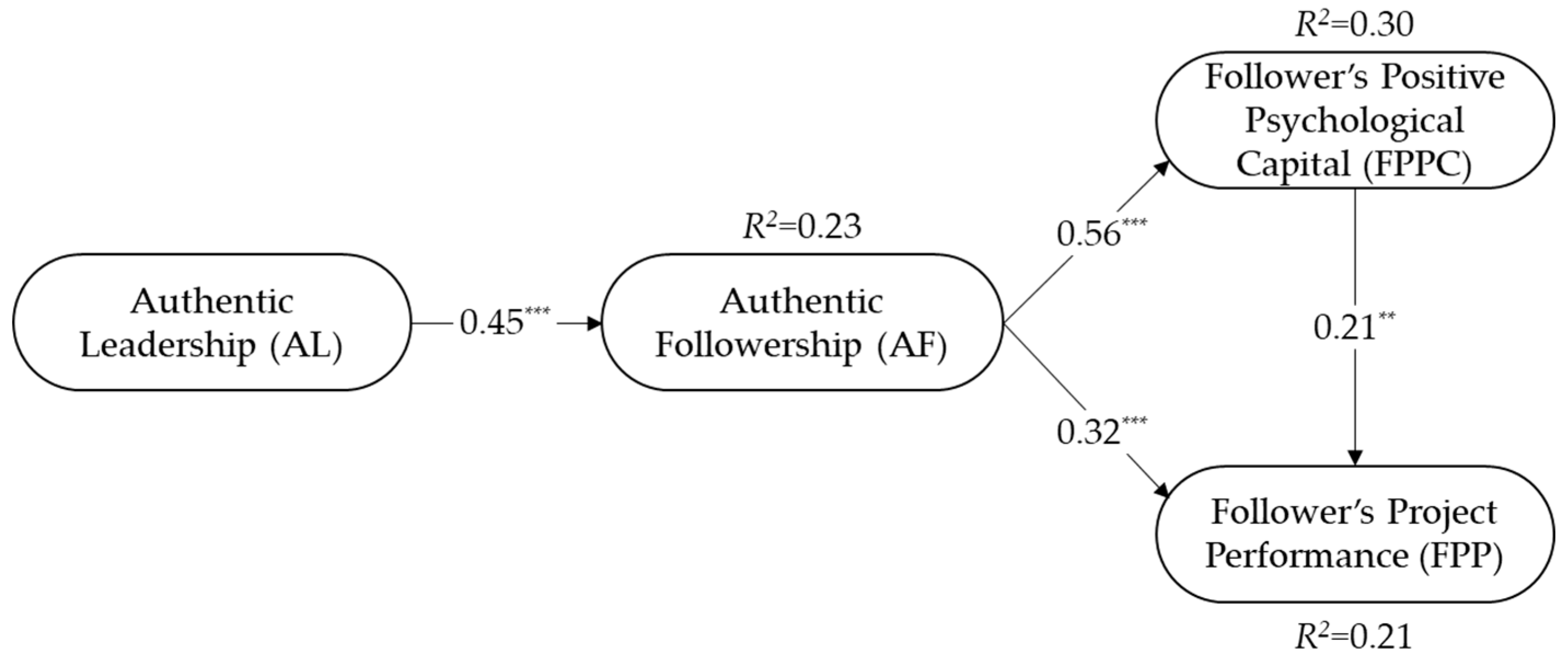

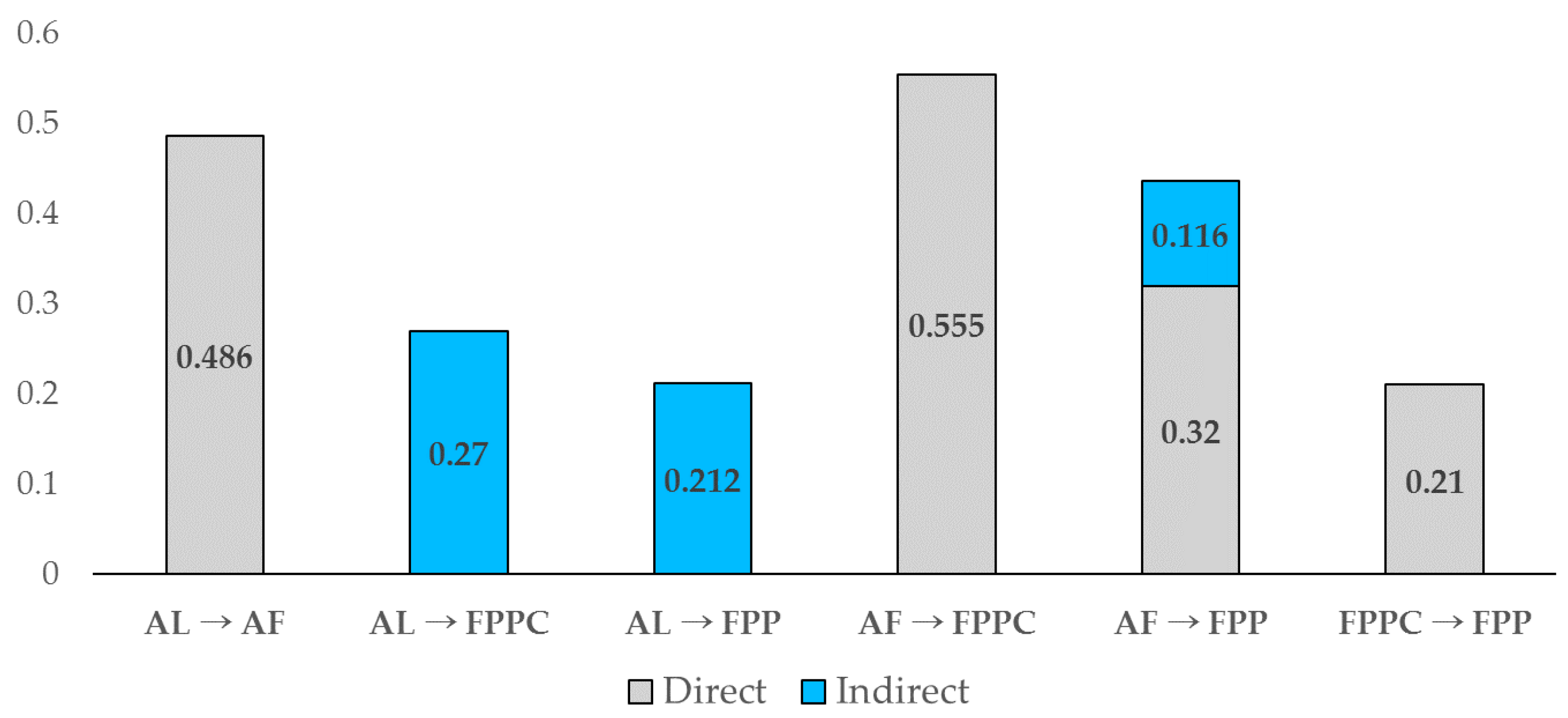

4.2. Structural Model Assessment Using PLS-SEM

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Telford, T.; Heat, T. Global Markets Rattled Amid Brexit, U.S.-China Trade War Standoffs; Dow Falls Nearly 300 Points. 2019. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/09/03/global-markets-wracked-with-anxiety-amid-brexit-us-china-trade-war-standoffs/ (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Hassan, A.; Ahmed, F. Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2011, 6, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Koene, B.A.; Vogelaar, A.L.; Soeters, J.L. Leadership effects on organizational climate and financial performance: Local leadership effect in chain organizations. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. Japan Ejects South Korea from Export ‘White List’ as Trade Relations Fray. 2019. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/donaldkirk/2019/08/02/japan-ejects-south-korea-from-export-white-list-as-trade-relations-fray/#4dd465a46eea (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Tepper, B.J.; Moss, S.E.; Duffy, M.K. Predictors of abusive supervision: Supervisor perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity, relationship conflict, and subordinate performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebel, M. These 7 Tech CEOs and Executives Lost Millions, along with the Companies They Helped Build. 2019. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/tech-ceos-executives-who-lost-millions-startups-failed-2019-8 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- De Lea, B. Theranos Founder Elizabeth Holmes in Court; Anatomy of a Fraud. 2019. Available online: https://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/theranos-elizabeth-holmes-sec-fraud (accessed on 20 August 2019 ).

- Witziers, B.; Bosker, R.J.; Krüger, M.L. Educational leadership and student achievement: The elusive search for an association. Educ. Adm. Q. 2003, 39, 398–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanchukwu, R.N.; Stanley, G.J.; Ololube, N.P. A review of leadership theories, principles and styles and their relevance to educational management. Management 2015, 5, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P.; Heck, R.H. Exploring the principal’s contribution to school effectiveness: 1980–1995. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 1998, 9, 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Epitropaki, O.; Butcher, V.; Milner, C. Transformational leadership and moral reasoning. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Duane, R. The essence of strategic leadership: Managing human and social capital. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 2002, 9, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J. Authentic leadership development. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, I.G.; Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Management innovation and leadership: The moderating role of organizational size. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, T.; Keller, R.T. Leadership in research and development organizations: A literature review and conceptual framework. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youndt, M.A.; Snell, S.A.; Dean, J.W., Jr.; Lepak, D.P. Human resource management, manufacturing strategy, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 836–866. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, J. UK Economy Shrinks for First Time since 2012. Brexit could Tip it into Recession. 2019. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/08/09/economy/uk-gdp-brexit/index.html (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Hoffman, K. Business Transformation Part 1: The Journey from Traditional Business to Digital Business. 2019. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2019/08/23/business-transformation-part-1-the-journey-from-traditional-business-to-digital-business/#2d8b8ff86e80 (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Gardner, W.L.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R.; Walumbwa, F. “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, P.D.; Abolafia, M.Y. The creation of trust through interaction and exchange: The role of consideration in organizations. Group Org. Manag. 2006, 31, 628–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Schaubroeck, J.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Marques, C.; e Cunha, M.P. Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sui, Y.; Luthans, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y. Impact of authentic leadership on performance: Role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. J. Org. Behav. 2014, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Sousa, F.; Marques, C.; e Cunha, M.P. Hope and positive affect mediating the authentic leadership and creativity relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agote, L.; Aramburu, N.; Lines, R. Authentic leadership perception, trust in the leader, and followers’ emotions in organizational change processes. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 52, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubovnikova, J.; Legood, A.; Turner, N.; Mamakouka, A. How authentic leadership influences team performance: The mediating role of team reflexivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Peus, C. Crossover of work–life balance perceptions: Does authentic leadership matter? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianci, A.M.; Hannah, S.T.; Roberts, R.P.; Tsakumis, G.T. The effects of authentic leadership on followers’ ethical decision-making in the face of temptation: An experimental study. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Wang, D.-S. Does supervisor-perceived authentic leadership influence employee work engagement through employee-perceived authentic leadership and employee trust? Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2015, 26, 2329–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; Eilam, G. “What’s your story?” A life-stories approach to authentic leadership development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Anseel, F.; Gardner, W.L.; Sels, L. Authentic leadership, authentic followership, basic need satisfaction, and work role performance: A cross-level study. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1677–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M.H. Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychol. Inq. 2003, 14, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B. Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J. Authentic leadership: A positive developmental approach. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, R.; Morgeson, F.P.; Nahrgang, J.D. Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader–follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B. From passive recipients to active coproducers, followers’ roles in the leadership process. In Follower-Centered Perspectives on Leadership: A Tribute to the Memory of James R. Meindl; Shamir, B., Pillai, R., Bligh, M.C., Uhl-Bien, M., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, UK, 2007; pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.B., Jr.; Read, S.J. Self-verification processes: How we sustain our self-conceptions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 17, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, B.; Swann, J.; Buhrmester, M.D. Self-verification: The search for coherence. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 405–424. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.B., Jr.; Milton, L.P.; Polzer, J.T. Should we create a niche or fall in line? Identity negotiation and small group effectiveness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Org. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; McMahan, G.C. Theoretical perspectives for strategic human resource management. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.R., III; Van Buren, H.J. Organizational social capital and employment practices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Luthans, K.W.; Luthans, B.C. Positive psychological capital: Beyond human and social capital. Bus. Horiz. 2004, 47, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.L.; Cogliser, C.C.; Davis, K.M.; Dickens, M.P. Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, L.; Caza, A.; Levy, L. Authentic leadership and follower development: Psychological capital, positive work climate, and gender. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 2011, 18, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.M.; Luthans, F. Relationship between entrepreneurs’ psychological capital and their authentic leadership. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 254–273. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F. The impact of positivity and transparency on trust in leaders and their perceived effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, M.; Pringle, C.D. The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Buckley, F. Work engagement and its relationship with state and trait trust: A conceptual analysis. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2008, 10, 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Hannah, S.T. The relationship between authentic leadership and follower job performance: The mediating role of follower positivity in extreme contexts. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, A. Exploring predictors of organizational identification: Moderating role of trust on the associations between empowerment, organizational support, and identification. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 2010, 19, 409–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Res. Dev. Quart. 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.J.; Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhang, Z. Psychological capital and employee performance: A latent growth modeling approach. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Li, W. The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Manag. Org. Rev. 2005, 1, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M.H.; Goldman, B.M. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 38, 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate—Employee performance relationship. J. Org. Behav. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, Essex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Raykov, T. On measures of explained variance in nonrecursive structural equation models. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J.; Seo, J.; Roh, T. Leader’s authentic leadership and follower’s project performance. J. Dig. Converg. 2019, 17, 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Scully, J.A.; Sims, H.P., Jr.; Olian, J.D.; Schnell, E.R.; Smith, K.A. Tough times make tough bosses: A meso analysis of CEO leader behavior. Leadersh. Q. 1994, 5, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Focus | Study Sample | Source |

|---|---|---|

| AL, organizational citizenship behavior, work engagement, empowerment | 387 followers, 129 supervisors from two Chinese telecom firms | [25] |

| AL, psychological capital, creativity | 201 employees from 33 commerce organizations in Portugal | [26] |

| AL perception, trust, follower’s emotions | 102 human resource managers in Spanish companies with over 50 employees | [29] |

| AL, reflexivity, self-regulation, team performance | 206 participants from 53 work teams in the UK and Greece | [30] |

| AL, leader-member exchange, psychological capital, follower performance | 801 employees from Chinese logistics | [27] |

| AL, positive affect, hope, creativity | 219 employees from 37 retail organizations in Portugal | [28] |

| AL, conservation of resources, crossover, job satisfaction, work-life balance | 121 employees from different German firms | [31] |

| AL, temptation, ethical decision-making, guilt appraisal | 118 MBA program students at two universities in United States | [32] |

| Employee trust, employee-perceived AL, employee work engagement, supervisor-perceived AL | 160 of supervisors and employees from firms in Taiwan | [33] |

| Variable | Classification | Total | Early Respondents | Late Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 100 | 57.14 | 48 | 55.81 | 52 | 58.43 |

| Female | 75 | 42.86 | 38 | 44.19 | 37 | 41.57 | |

| School year | 2 | 54 | 30.86 | 32 | 37.21 | 22 | 24.72 |

| 3 | 53 | 30.29 | 29 | 33.72 | 24 | 26.97 | |

| 4 | 68 | 38.86 | 25 | 29.07 | 43 | 48.31 | |

| Experience of leader | Yes | 112 | 64 | 56 | 65.12 | 56 | 62.92 |

| No | 63 | 36 | 30 | 34.88 | 33 | 37.08 | |

| Experience of team project | 0 | 10 | 5.71 | 5 | 5.81 | 5 | 5.62 |

| 1 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3.49 | 4 | 4.49 | |

| 2 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 6.98 | 8 | 8.99 | |

| 3 | 26 | 14.86 | 10 | 11.63 | 16 | 17.98 | |

| >4 | 118 | 67.43 | 62 | 72.09 | 56 | 62.92 | |

| International internship | Yes | 56 | 32 | 11 | 12.79 | 45 | 50.56 |

| No | 119 | 68 | 75 | 87.21 | 44 | 49.44 | |

| Major in Management | Yes | 137 | 78.29 | 64 | 74.42 | 73 | 82.02 |

| No | 38 | 21.71 | 22 | 25.58 | 16 | 17.98 | |

| Construct | Code | Scale Item | Factor Loading | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic leadership [25,27] | AL1 | Our team leader seeks feedback from team members to improve their interaction with them. | 0.83 *** | 3.97 | 0.96 |

| AL2 | My team leader knows when to reconsider his position. | 0.83 *** | 3.70 | 1.00 | |

| AL3 | My team leader knows how his actions affect his team. | 0.80 *** | 3.98 | 0.99 | |

| AL4 | Our team leader makes good decisions. | 0.71 *** | 3.99 | 0.96 | |

| AL5 | My team leader strongly encourages me to act with confidence. | 0.83 *** | 3.94 | 1.02 | |

| AL6 | Our team leader follows ethical standards for difficult decisions. | 0.76 *** | 3.86 | 0.98 | |

| AL7 | Our team leader admits when he makes a mistake. | 0.79 *** | 4.17 | 0.83 | |

| AL8 | Our team leader encourages all team members to express their ideas. | 0.84 *** | 3.97 | 0.95 | |

| AL9 | Our team leader reviews the data thoroughly before making a decision. | 0.85 *** | 3.97 | 1.00 | |

| AL10 | Our team leader listens to various opinions carefully before making a conclusion. | 0.89 *** | 4.01 | 0.95 | |

| Authentic followership [35] | AF1 | I show a behavioral consistent with my beliefs as a team member. | 0.79 *** | 3.89 | 0.87 |

| AF2 | I make decisions that fit my values as a team member. | 0.87 *** | 4.16 | 0.71 | |

| AF3 | I act with confidence as a team member. | 0.82 *** | 3.98 | 0.88 | |

| AF4 | I express my feelings honestly as a team member. | 0.78 *** | 3.78 | 0.98 | |

| Follower’s positive psychological capital [26,64] | FPPC1 | I can easily cope with the stress of playing a role. | 0.80 *** | 3.29 | 1.10 |

| FPPC2 | I can cope well when faced with a demanding role. | 0.86 *** | 3.79 | 0.78 | |

| FPPC3 | I always try to be positive about what I’m doing. | 0.81 *** | 3.95 | 0.91 | |

| Follower’s project performance [61,62] | FPP1 | I do my job well in my team. | 0.84 *** | 4.29 | 0.67 |

| FPP2 | I get my work done within the time set by the team. | 0.74 *** | 4.19 | 0.75 | |

| FPP3 | I am responsible for my role in the team. | 0.89 *** | 4.27 | 0.67 | |

| FPP4 | I adhere to the formal requirements set by the team. | 0.75 *** | 4.29 | 0.69 |

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | rho | AVE a | AL | AF | FPPC | FPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.66 | 0.81 b | |||

| AF | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.49 | 0.81 | ||

| FPPC | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.82 | |

| FPP | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.81 |

| Statistics | AL → AF → FPPC | AL → AF → FPP |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| Standard error | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| z-statistic | 5.10 | 3.10 |

| p-value | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Conf. interval (N) | (0.166, 0.373) | (0.056, 0.254) |

| Conf. interval (P) | (0.173, 0.379) | (0.066, 0.261) |

| Conf. interval (BC) | (0.173, 0.379) | (0.071, 0.268) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tak, J.; Seo, J.; Roh, T. The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Authentic Followership, Positive Psychological Capital, and Project Performance: Testing for the Mediation Effects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216028

Tak J, Seo J, Roh T. The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Authentic Followership, Positive Psychological Capital, and Project Performance: Testing for the Mediation Effects. Sustainability. 2019; 11(21):6028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216028

Chicago/Turabian StyleTak, Jingyu, Jeongeun Seo, and Taewoo Roh. 2019. "The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Authentic Followership, Positive Psychological Capital, and Project Performance: Testing for the Mediation Effects" Sustainability 11, no. 21: 6028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216028

APA StyleTak, J., Seo, J., & Roh, T. (2019). The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Authentic Followership, Positive Psychological Capital, and Project Performance: Testing for the Mediation Effects. Sustainability, 11(21), 6028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11216028