Abstract

Academic institutions like other business organizations strive to achieve, maintain, and sustain their competitive advantages. In this study, we examined the influence of the “strategic human resources management (HRM) practices” on the achievement of “competitive advantages” that will be sustainable, with an evaluation of the mediating role of “human capital” development, and the commitment of employees in an academic environment. Six hundred questionnaires were randomly distributed to the employees of selected universities in Erbil City of Iraq. Structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques were employed for the analysis with the use of Smart Partial Least Square PLS. Findings from our study revealed a linear and positive influence of the strategic HRM on the sustainability of “competitive advantages”; strategic HRM was also found to positively influence human capital development and the commitment of employees to the institutions; the influence of both human capital development and employees’ commitment were found to have a partial mediation in the strategic HRM practices and sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) relationship. Finally, theoretical and management implications were suggested.

1. Introduction

In the dynamic and competitive business world of today, where the exchange of ideas is proficient, a “sustainable competitive advantage” (SCA) is no longer deep-rooted in the organization’s physical resources but in the organization’s nonphysical human resources [1,2]. In view of these findings, the attention of scholars has been on the factors that could be instrumental to the achievement of SCA. O’Reily and Pfeffer [3] opined that the world we are in today is the one wherein “knowledge and intellectual capital” [4] is required instead of “physical capital”. Thus, the study believes it is becoming significant in the business world where people can be effective and efficient in developing innovative goods and services. It is on this note that other scholars have attempted to understand the particular factors that could enable an organization to achieve SCA. Barney [5] investigated the relationship between SCA and organizational resources and found that every organization operates with a tacit knowledge and has the potential to improve, SCA.

Meanwhile, in the efforts of scholars to examine the nexus in strategic human resources management practices, a behavioral approach has been commonly used. Behavioral approaches, which identify divergent role behaviors as significant to the kind of strategy that is being pursued by an organization, are found in the literature to be the most often used theory to explain the nexus in strategic human resources management (HRM) practices. Much emphasis is placed on individual employee behavior as a mediator between organization strategy and the result by this approach or as a mediator between strategic HRM and SCA [6]. The behavioral school of thought is of the view that divergent behavior roles are important in determining the kinds of strategies that an organization engages in [1]. It has been established in the literature that an employee stands out as one of the major sources of achieving SCA in an organization. Thus, the integrative model for strategic HRM, which combines rational and progressive approaches and is ingrained in some theories—for instance resource-based view (RBV), social exchange theory (SET), and behavioral-based view—are found as an appropriate approach to strategic HRM and SCA. This research utilized the perception of HRM practices to explain in detail from the angle of human capital development and the commitment of employees to their organization. Therefore, this study will examine the relationship between the strategies deployed by the universities in Iraq and the sustainability of their competitive advantages by also evaluating the mediation role of human capital development and employee commitment. In accordance with the theories highlighted above, this study aims at determining the impact of “strategic HRM practices” on the SCA within academic institutions through the evaluation of the mediating function of human capital development and “employee commitment”. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the theoretical background to the study and development of the hypotheses for the study. This is followed in the subsequent section with research methodology. In this section, the instrument and procedure for data collection are discussed. In Section 4, data analysis techniques employed for the study are discussed; the psychometric properties of the constructs and structural model testing results are also presented. The last section contains a discussion of the results in which the theoretical and managerial implications are discussed, and the study limitations and suggestions for further study are wrapped up the section.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

The essential factor that will lead an organization to have a competitive advantage is human capital, and strategic HRM is introduced to manage employee skills, capacity, and knowledge in an efficient and effective way to significantly influence the strategic target achievement of an organization. In view of these factors, McMahan, Virick, and Wright [6] refer to “strategic HRM practices” as the structure that firm’s HR implements towards achieving organization objectives. By way of its application, strategic HRM practices provide a link between the business requirement and the activity of a firm [7,8], “unite and guide the employees in line with the business strategies” [9], and make provisions for a firm to achieve a competitive advantage [10,11]. Boxall [12] further stated that “strategic HRM practices”, when applied in an organization, will enable a firm to have a competitive and inimitable advantage. Strategic HRM practices are more of an internal factor that influence an organization’s performance rather than the external resources. In this context, the human resource is perceived as a significant resource that should be deployed with other resources to enhance firm’s performance. In the view of Findikli, Yozgat, and Rofcanim [7], strategic HRM practices should be viewed as a scheme that sets to enhance, motivate, and reduce employee turnover so as to ensure the effective implementation and the success of the firm and its employees. This view corroborates the study of Chang and Huang [13], which proved that a significant influence of human resource practices is found on positive organizational outcomes. Guest [14] opined that the adoption and integration of strategy decisions into HRM systems is the significant distinction that links strategic HRM practices to HRM. Previous research on the relationship between strategic HRM practices and SCA has centered on motivation and how it influences employees in achieving organizational strategy. The study concludes that SCA can be built by aligning strategic HRM practices with organizational strategy [15]. The study argued that these are valuable assets to the organization, which are scarce, distinct, and difficult to substitute or imitate, so as to assist the organization to improve its sustainable competitive advantage.

2.1. Strategic Human Resources Management Practices and Educational Institution

Universities, like every other organization, strive to survive in today’s dynamic and complex business environment. Universities aim to develop and survive in the challenging market environment, and as such, make efforts to develop its strategic resources so that its goals can be achieved. Meanwhile, the idea of human resource management in educational institutions, like universities, is a new trend. This could be because university employees are considered to be knowledgeable; therefore, more attention is paid to academic development in comparison to the attention devoted to the management of human capital. This is evident in the scant literature on the subject matter. Universities, like other organizations, are being confronted with the challenges of financial and nonfinancial challenges [16], coupled with international competition, and the dynamic and changing requirements from the labor market [17,18]. Warner and Palfrayman [18] examined management processes in a university environment, and they found that a “people-oriented approach” that places its focus on the best practices and acknowledges “academic excellence” is a viable system. However, while public university management structures are more nonprofit- and people-oriented, meaning the expenditures are more than just about profit, most of the private universities are the opposite. Similar to other organizations, universities are often influenced by political, social, and economic changes in society. As a result of these considerations, there is rivalry among the universities [19]. They all strive to attain their objectives and to also achieve sustainable competitive advantages [20]. Meanwhile, in order to bring strategic HRM into universities, the administrative framework needs to be integrated within the academic process. However, it is quite unfortunate that these will face some difficulties in aligning the academic process with the management system. This is a result of the nature of universities and colleges that create a distinction from other business. It is in line with this that Pausits and Pellert [21] conducted a study and suggested that universities and colleges must accept changes as a permanent feature in their culture, like any other business organization, and then introduce strategic HRM practices. Furthermore, Smeenk et al. [22] argued that variance availability and some different location consistencies in relation to the appropriate HRM policy and procedure will positively influence employee performance. For instance, in Iraq, the problem of achieving sustainable competition is unclear. The challenge is not different from the one pointed out by Middlehurst [23], who asserted that the challenge facing universities and colleges, among others, was a result of university education privatization, which increases competition. As such, Iraqi universities are faced with the challenge of determining a framework that is suitable to the achievement of SCA. Meanwhile, a recent study by Emeagwal and Ogbonmwa [1] suggests, among other things that for a university to achieve sustainable competitive advantage”, strategic HRM practices must be effectively applied.

2.2. Sustainable Competitive Advantage

In the competitive business world of today, there exists the need for every firm or organization to have the wherewithal to harness outstanding achievement through its distinctive organization structure in order to excel beyond others in the same market. This is often referred to as “competitive advantage.” The issue of how an organization can achieve these excellent results in today’s competitive market has been a subject of interest to researchers. Kuncoro and Suriani [24], and Mahdi and Almsafir [16] opined that the implementation of a value-creating strategy that is not simultaneously being implemented by any other organization in the same market is said to have a competitive advantage. In other words, a firm needs to successfully implement the strategy that will enhance their organization’s performance, which would cause the firm to have a competitive advantage over either the current or potential firm coming into the market. In order to achieve these competitive advantages, most organizations formulate a business strategy that will enable them to manipulate various resources that are under their control and which the firm knows have the ability to generate a competitive advantage.

Covin and Lumpkin, [25], supported by Pratono et al. [26], however, argued that in a rapidly changing world market where competitive advantage is believed to not be sustainable, strategic human resource practices are found to be a significant source through which we can have a clear understanding on why some firms fail in achieving and sustaining a competitive advantage, while others achieve it [25,26]. Kuncoro and Suriani [24] added that for a firm to be the market leader, which would be a result of having competitive advantage, such a firm must have what it takes to be ahead of the present or new entrants into the market. From the description of competitive advantage, it is clear that competitive advantage is significant to the performance of any organization in order to survive and be placed in a prominent position in the market. This advantage, thus, depends on the type of competitive advantage that the firm wants to deploy and the area to be covered with their activities [24]. The most important features that put any organization on the path to competitive advantage is when they are implementing strategies that are not similar to other players in the market. More so, the advantage will become sustainable when current or potential competitors find it difficult to imitate or have a substitute [27,28,29].

2.3. Strategic HRM Practices and Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Strategic human resources management (HRM), in the words of Saha and Gregar [4], is viewed as a planned structure of human resources being used by a firm and other activities that are targeted towards achieving the organizational goals. The idea in their description of strategic HRM is the ability of a firm to influence its performance with the management of its human resources and also combine with other activities to make it a system, rather than a single entity at a strategic level. Even though this idea has been criticized, the significant influence of human resources on organization performance has been documented in the literature. The number of studies that are in support of the significant relationship has been on the rise. Several measures have been employed in the literature to measure HRM, for instance, high-performance and high-involvement work systems, HR orientation, work–life balance, and individual aspects of HR [30,31,32,33,34]. However, the search for sustainable competitive advantages by the firms has largely been influenced by technological advancement, globalization, and other factors [35].

Meanwhile, literature on the competitive advantage is plentiful, especially on sustainability determinants. Some authors highlighted factors such as a company’s dynamic capabilities [36,37], innovation [5,9], intellectual capital [36], and human capital [38]. However, D’Aveni et al. [39] and Wiggins and Ruefli [40] argued that there are some forces that are likely to diminish the competitive advantages or cause them to evaporate over time, while Huang et al. [41] opined that such thinking of unsustainability of competitive advantage is a destructive assumption. In addition, some authors argue that for an organization to achieve long-term competitive advantages, there is a need for such firms to develop their human resources in a systemic way that will enable the firm to use their tacit knowledge in order to have an edge over its competitors [42,43]. By doing these things, the type of employee management system implemented is significant to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage [44]. Increases in strategic concepts and management gives room for the firm’s interest on how they can position their organization strategically so as to be able to compete effectively in the market. Subsequent to that, the firms will begin to develop more interest as to how they can harness the potential of their human resources with quality management that contributes to the process of having a competitive advantage [45]. Previous studies have concentrated on some aspect of HRM functions suggesting that it should be in tandem with the strategy deployed by the organization to achieve SCA. Meanwhile, there is a need to examine the direct influence of the bundles of HRM on the sustainable competitive advantage.

Based on the above thoughts, our first hypothesis is formulated:

H1:

Strategic HRM practices positively impact sustainable competitive advantage.

2.4. Relationship among Strategic HRM Practices, Employee Commitment, and Human Capital Development

The complexity and dynamism of today’s business world has made the development of human capital significant by having identified it as one of the elements of SCA [5]. Thus, the importance of human resource management as a system framework in human capital development that leads to sustainable competitive advantage cannot be ignored [46,47]. Collins and Clark [48] opined that an organization can have an impact on the “skills, attitude and behaviors” [48] of an individual employee to be efficient in their job and contribute to the organization’s objectives through human resource practices [47,48]. There are numerous studies in the literature that show the influence of human resource practices, either collectively or individually, to be positive on a firm’s performance [49]. A common trend in the empirical literature has been that strategic HRM practices impact positively on the firm’s performance through employee commitment. Though, some studies failed to agree with these findings [34]. Nevertheless, Jackson et al. [46] and Emeagwal and Ogbonmwan [1] found a positive influence of strategic HRM on employee behavior, and that this further led to a competitive advantage for the firm. The study of Emeagwal and Ogbonmwan [1] further revealed that holistic employee training enhances the employee’s knowledge, competency, and capacity. Jiang et al. [50] added that when a firm develops the human capacity of their employee, it enhances the usefulness and competency of the employee. The study further noted that other functions of HRM, for instance, job security, rewards, and incentives, boost the morale of the employee and reduce employee turnover, while nonrigid work schedules and team-learning will boost employee morale and the acquisition and transfer of new knowledge [46].

In consideration of the above arguments, developing the capacity to ensure an employee commitment that will promote the firm’s performance is linked to the strategic HRM practices adopted by the organization. Therefore, from the perspective of a “behaviorally based view” [51], this gives an indication that strategic HRM practices used by an organization increase the positive behavior of the employee and, thus, lead to a desired outcome for the organization. Moreover, Conway and Monks [33] argued that enhancement of an employee’s positive behavior can be achieved with the organization’s commitment to development through HRM systems, and they concluded that strategic HRM significantly influenced employee commitment. Similar results were found in a recent study by Emeagwal and Ogbonmwan [1] that corroborated the positive and direct influence of “strategic HRM practices” on both human capital development and “employee commitment”.

Therefore, our second hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H2:

Strategic HRM practices have a direct and positive influence on (a) human capital development and (b) employee commitment.

2.5. Nexus among Sustainable Competitive Advantage, Employee Commitment, and Human Capital Development

In the literature, three categories are recognized in the concept of human capital [51]. Some view human capital as a tangible resource that is considered to be more productive than any asset that an organization could possess [52], which comprises the embedded skills, ability, and knowledge of the employees. [17,53,54,55]. Another aspect views it from the angle of how skill, knowledge, and capability are accumulated through formal education or experience [53,56]. The last category is from the perspective of production orientation. In addition, the process wherein an employee is engaged in training and development to enhance their performance by developing their expertise through organization development could be regarded as human capital [17,52,57].

In this regard, human capital development could be considered as a firm’s investment that will improve the competence of their employees to achieve competitive advantages [53]. This implies that any organization that aims at achieving SCA needs to invest in its employees to have all the requisite knowledge and skills that are required in a competitive business environment in order to be effective and efficient in the discharge of their duties [52]. The significance of human capital development in a firm’s performance and in achieving sustainable competitive advantages has been documented in the literature [9,17].

Looking at it from the RBV theory perspective, the tacit knowledge that will give an organization a competitive advantage will emanate from internal development [1,58]. It is when this is in process that the employee will have a sense of belonging in the company, and, in turn, they will enhance their commitment to the company. Employee commitment is when an employee has passion for what he/she is doing and feels secure and ready to invest him/herself with the aim of contributing to the success of the organization. In the words of Alnidawi [57], the study opined that when an employee has a positive emotional attachment to the company and is proud of being a member, he/she will be ready to exercise his/her efforts in the organization for achieving success. Some previous studies established that high-performance work practices (HPWP) enhance an employee’s knowledge and skills [49,59], and that the contribution of strategic HRM practice in enhancing the employee’s productivity has an attendant effect on a firm’s performance [60]. In addition, while some studies found that a positive influence of human capital development on organization performance gives them competitive advantages [1,47,61], some others found negative influences of “employee commitment” on the SCA [1,62,63,64].

In view of the above, we formulate our third hypothesis as follows:

H3:

(a) Human capital development and (b) employee commitment have a linear and positive relationship with sustainable competitive advantage.

2.6. Mediating Role of Human Capital Development and Employee Commitment

HPWP consists of different components, such as staffing, reward, and incentive for employee training and development, as well as employee performance management, which is aimed to develop an employee’s skills, knowledge, and behavior that will enable him/her to contribute to the organization’s competitive strategy [47,59]. With the advent of technology, an organization could seek the deployment of modern technological equipment; however, without a competent and trained employee to put this equipment into use, the organization’s purpose might not be achieved [65,66]. In other words, the objectives and mission of an organization can only be achieved through strategic HRM practices [60,65,67]. The uniqueness of an organization can only be achieved via a high performance from its employees [66]. It is believed that organizational performance can only be achieved through strategic HRM practices when the employees are committed [58,61,63]. Some studies claim that a bidirectional relationship exists between human capital development and organizational performance [55]. Even though a positive influence of strategic HRM practice on human capital development is documented in the literature, Godard [68] and Posthuma et al. [69] argued that strategic HRM practices are rare and partial.

The combination of RBV and behavioral theories to examine the mediating role of human capital development and “employee commitment” in this study proposed that strategic HRM practices will contribute to an organization’s competitive advantage with an effective management of human capita, its development, and “employee commitment”. The employee attitude and behavior, referred to here as “employee commitment”, emanate from the behavioral view that it will mediate the relationship between “strategic HRM practices” and SCA by integrating the social exchange theory (SET). It has been established in the literature that the development of human capital by any organization will result in the firm having a competitive advantage [66,70].

In the study of Widodo and Moch Ali Shahab [67], it was affirmed that a preoccupation with the intent of finding a strategic technique that drives the organization and the resultant HRM systems suggests that human resources are confined to and are required to drive the strategic objectives of the organization. Building an entire arrangement of work affiliations subject to a shared normal for targets and needs must have a touch of strategic HRM. Similarly, in resonance with the social exchange theory, strategic HRM practices elevate improvement practices that strengthen persuasive duties to react in a significant way [71]. According to the RBV theory, it is demonstrated that when an organization acknowledges an HRM approach, where an individual is gainful as an asset in accomplishing organization aims, there is a probability that the firm would have to arrange long-term investments to improve the employee’s aptitudes, learning, and restraints, and the organization will, in a similar way, center around arousing employees’ interests and to place more attention on the critical need of employees to be above profit-making. In that case, sustainable competitive advantages are relied on to be developed [72]. Organizations should acknowledge HRM practices that are most expected to improve the degree of developing human capital and to shape employee habits and behaviors to empower organizations to achieve their plan [46]. HRM is referenced to have the decision to give a powerful system that can bolster and direct the degree of competence, innovativeness, and inventiveness of its employees, to reveal to them satisfactory conduct, and to build up the competency of its employees so as to align them with their strategy.

In view of the above, the following fourth hypothesis are formulated:

H4:

(a) Human capital development and (b) employee commitment partially moderate the relationship between strategic HRM practices and sustainable competitive advantage.

3. Research Methodology

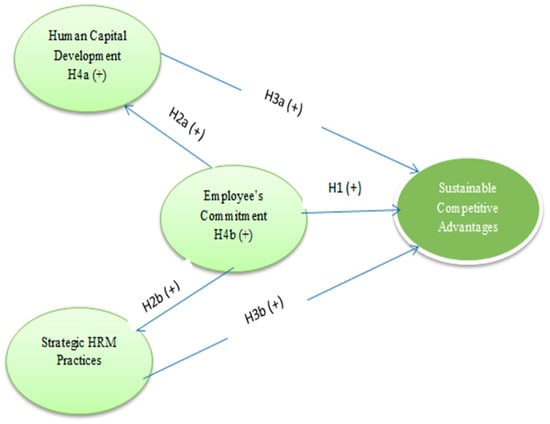

In our study, the research framework as depicted in Figure 1 indicates the relationships among our variables. A relationship between the strategy deployed by an organization to effectively manage their human resources and how their competitive advantage achieved could be sustained is proposed in the framework, evaluating the mediating function of human capital development and employee commitment. In our study, we contend that the strategy deployed by an organization for its HRM practices determines how the organization can sustain the competitive advantage achieved in the market by hypothesizing that human capital development and “employee commitment” will partially mediate the relationship. In other words, strategic HRM practices, human capital development, and employee commitment will have a linear and indirect influence on sustainable competitive advantage.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3.1. Measures

Our model was measured with four latent variables: strategic HRM practices (SHRMP), human capital development (HCD), employee commitment (EC), and sustainable competitive advantage (SCA). The items for each of the variables were adapted, modified, and were scaled on five-point Likert scale. SHRMP was measured with six items adapted from Aryanto, Fontana, and Afiff [30 Emeagwal and Ogbonmwan [1], Sahar and Gregar [4], and Zehir et al. [66] (see Appendix A). As for human capital development, it was measured with four items and was adapted from Kadir et al. [61], Mahdi, Nassar, and Almsafir [17], Sanches, Marin, and Morales [47], and Todericiu and Stanit [60] (see Appendix A). Employee commitment was measured with four items that were adapted from previous studies [1,66] (see Appendix A). Lastly, the sustainable competitive advantage was measured with three items that were adapted and modified from previous studies [1,17,24] (see Appendix A). In addition, gender, educational level, status of employment, and type of university (private/public) were utilized as the control variables.

3.2. Data Collection

The city of Erbil was randomly selected among the four cities within the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Out of the 4 public and 5 private universities that are available within the city, 3 public and 4 private universities allowed us to distribute the questionnaires to the university staff. In the 7 universities that were selected, 600 questionnaires were distributed. Out of the 600 distributed, 91 questionnaires (15.17%) were unreturned; in other words, 84.83% were returned. However, out of the 509 questionnaires (84.83%) that were returned, in the course of coding, 54 (9%) were found to be uncompleted, and these were removed, leaving us with 455 questionnaires (75.83%) that were utilized for the analysis. From the descriptive analysis, 241 (53%) of the respondents were male, while the remaining 47% were female. As for the age of respondents, 34.3% of the respondents were between the ages of 18–30 years, and the remaining age groups comprised 31–45 years (37.6%), 46–60 years (24%), and above 60 years (4.2%). Descriptive analysis of the educational level of the respondents comprised 5.3% (high school), 9% (diploma), 24% (bachelor’s degree), 25.88% (master’s), and 38.12% (PhD). The employment status of the respondents indicated that 41.1% of the respondents were academic staff, while 58.9% were nonacademic staff. Lastly, descriptive analysis for the type of university showed that 52.1% of the respondents were from private universities, while 47.9% were from public universities. The mean, standard deviation, and the correlations among the variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Correlations among the observed variables.

4. Data Analysis and Results

This study employed Partial Least Square- Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) with the path-weighing scheme to analyze our data. As argued by Dijkstra [73], the path-weighing scheme is preferable because it provides the highest R2 value for endogenous latent variables and is generally applicable for all PLS path mode specifications and estimations. The technique was in line with Petter [74], who posited that PLS-SEM is efficient for prediction by reducing the explained variance in the dependent variables, most especially when the data are in contrast to the normality assumption and certain important regressors are excluded from the model. SmartPLS 3 was utilized for data analysis, and the psychometric properties of the construct were examined through factor loadings of the items [75], including average variance extraction [76,77], composite reliability [77,78], variance inflation factor (VIF) [76], and, discriminant validity through Fornel–Larcker criteria [79] and Heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) [80]. The theoretical construct of the study was evaluated utilizing structural equation modeling. In order to increase the computational time and test for the significance of the PLS-SEM results, subsample of 5000 was used for bootstrapping. Model-based bootstrapping was used in order to obtain accurate estimates of the p value for our estimated coefficients [81]. Lastly, model fitness was evaluated with the chi-square (2) measurement, normed fit index (NFI), size effect (f2), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR).

4.1. Measurement Findings

The findings from the psychometric properties’ analysis of our construct, as presented in Table 2 showed that the measurement items for SHRMP, HCD, EC, and CSA ranged between 0.60–0.92. Though some authors suggest factor loadings that are greater than 0.70 [75], some authors argued that a factor loading value between 0.50–0.60 can be sustained and accepted. In view of this, our results, as presented in Table 1, indicated that none of the item loadings was less than 0.60. Thus, we sustained and accepted the loadings for further analysis. The average variance extractions values for our latent variables were 0.56, 0.51, 0.58, and 0.51 for SHRMP, HCD, EC, and SCA, respectively. The values obtained for AVE were in line with Henseler, Hubona, and Ray [76] and Henseler [77], who suggested that an AVE value greater than 0.50 was acceptable. The suitability of our AVE values was an indication that the dominant factors out of a set of indicators were extracted. As for composite reliability, the values were far above the 0.70 threshold, as suggested by Nunnally and Berstein [78] and Hensler [77]. The acceptability of our CR values was an indication that our scaled items were internally consistent. Moreover, in order to examine significant and substantial contributions of all the items, the sign and the strength of the indicator weights as well as their significance were evaluated by assessing the variance inflation factor (VIF). The results, as presented in Table 2, showed that the items had VIF ratios that ranged between 1.10 and 1.74. This implied that the result was consistent with Henseler, Hubona, and Ray [76], who suggested that a value not less than 1 and greater than 5 was considered to be acceptable. In addition, the model fit statistics of our data indicated the fitness of our model (SRMR = 0.092; 2 = 626.42; NFI = 0.574; rms theta = 0.175).

Table 2.

Validity and Reliability for Constructs.

In order to examine whether the constructs in our model correlated with each other, both the Fornel–Lacker [79] ratio and Heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt [80]) were utilized. Fornel–Larker postulates that a constructed AVE should be higher than all its squared correlations, while HTMT suggests that an HTMT value between 0.85 and 1 is sufficient to provide evidence of the discriminant validity of a pair of constructs. From our results, as presented in Table 3, the square roots of AVE that are indicated in the diagonal and bold (0.749, 0.713, 0.758, and 0.713) were all greater than the squared correlations for each construct respectively. Similarly, for the HTMT values, they were all less than 0.85, which is an indication that the two tests proved the discriminant validity of our construct. To ensure there was no common method bias (CMB) in our measurement, Harman’s one-factor test was employed to assess the common method variance, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. [82]. A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, and the result showed that no single factor was dominant. Moreover, due to the shortcomings of Harman’s one-factor test, a full collinearity test, through the examination of variance inflation (VIF) in PLS-SEM as argued by Kock [83], was performed. Results as presented in Table 2 showed that the measurements were free from CMB because none of the VIF values was less than 1 and greater than 5, as the recommended threshold.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

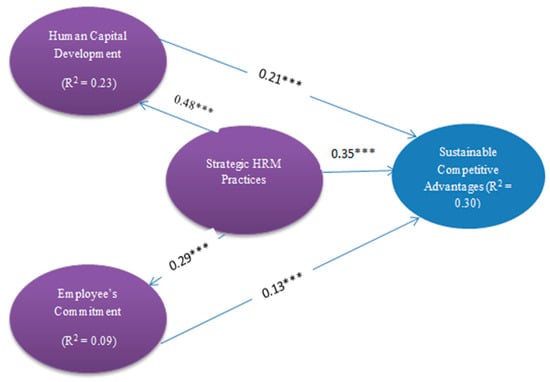

4.2. Structural Model Testing

The results for our model testing, as summarized and presented in Table 4 and Figure 2, showed that about 22% variance of human capital development could be explained by strategic HRM practices, 9% variance of employee commitment could be explained by strategic HRM practices, while 30% variance of sustainable competitive advantage could be explained by human capital development, strategic HRM practices, and employee commitment. This is a result of the coefficients of determination (R2) for DHC, EC, and SCA (0.22, 0.09, and 0.3, respectively) as depicted in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Hypothesis Testing.

Figure 2.

Structural model results. Note: *** denote 1% significance level

Moreover, the path coefficients, as presented in Table 4, showed that strategic HRM practices exerted a significant, positive, and direct influence on SCA (β = 0.345, t = 6.981); therefore, hypothesis 1 was accepted. This implied that a unit change in the strategic HRM practices of the Iraq universities, about a 0.35 increase, will impact the sustainable competitive advantage while holding all other variables constant. The findings further showed that hypothesis 2a,b was accepted as a result of the significant positive and direct influence of strategic HRM practices on human capital development (β = 0.477, t = 11.936) and the positive and direct influence of strategic HRM practices on employee commitment (β = 0.293, t = 6.691). This result implied that, while holding all other variables constant, a unit change in strategic HRM practices in Iraqi universities will influence about 0.48 unit positive changes in human capital development and 0.29 positive changes in EC. The direct influence of human capital development and employee commitment was evaluated on the sustainable competitive advantage. Results as presented in Table 4 indicated that both hypotheses 3a (β = 0.214, t = 4.292) and 3b (β = 0.132, t = 2.924) were accepted as a result of their positive and significant coefficients. In other words, a unit change of human capital development will increase the chances of Iraq universities to achieve competitive sustainable advantages by about 0.214, while a unit change of 0.132 in employee commitment will positively increase the chances of Iraq universities in achieving sustainable competitive advantages, when holding all other variables constant. Hypothesis 4a,b was to examine the partial mediating influence of both human capital development and employee commitment in the relationship between strategic HRM practices and sustainable competitive advantages. The findings revealed that human capital development partially mediated the influence of strategic HRM practice on sustainable competitive advantages (indirect effect = 0.102, t = 4.02), while employee commitment also showed a positive, partial mediation between strategic HRM practices and sustainable competitive advantages (indirect effect = 0.039, t = 2.7). Thus, the two hypotheses were accepted.

Furthermore, because the path coefficients were found to be influenced by the number of other explanatory variables, as well as the correlation among them, Cohen [84] opined that it is not helpful in comparing the size of an effect across the model. Cohen [84], therefore, suggested that effect sizes with values that are >0.35, >0.15, and >0.02 could be considered as strong, moderate, and weak, respectively. In view of the above, the effect sizes (f2) of our constructs showed that human capital development, employee commitment, and strategic HRM practices had weak effect sizes (0.048, 0.022, and 0.13, respectively) on sustainable competitive advantages, while strategic HRM was found to have a moderate effect size (0.29) on sustainable competitive advantage.

In addition, since the questionnaires were administered to both private and public universities, the type of university was included as a control variable. Gender, educational level, and employment status (whether academic or nonacademic) were also utilized as control variables. Our study found a positive relationship between the type of university and sustainable competitive advantages (β = 0.33, t = 7.58). The relationship was also found to be statistically significant. A negative and significant relationship was found between gender and sustainable competitive advantage (β = −0.078, t = 2.01), while negative and positive relationships were found between educational qualification and sustainable competitive advantage (β = −0.008, t = 0.21) and status of employment and sustainable competitive advantages, respectively (β = 0.029, t = 0.72).

5. Discussion

Our study was unique among previous empirical designs and behavioral research because it employed SEM techniques for the analysis. Further, SmartPLS 3 was utilized to run the analysis. The focus of our study was to examine the influence of strategic HRM practices on the achievement of competitive advantages that are sustainable in an academic environment, and we also evaluated the mediating function of human development and employee commitment. Universities and colleges, like every other business organization, are facing some challenges in the dynamic and complex competitive business environment. The challenges, among others, as highlighted by some studies are the privatization of the educational system, the changes in the requirements from the labor market [16], and international competition [16,17]. The Iraq educational system is not an exception to these challenges. Moreover, the issue of the nature and culture of the academic environment is what makes this study significant.

The theoretical implication of our research is specifically the examination of the influence of strategic HRM practices on sustainable competitive advantage through the mediation of human capital development and employee commitment (which can be determined by the attitude and behavior of the employee) anchored on integrating both a “resource-based view” (RBV) and “behavioral theory” and applying it to a university management system. Our results, which established the significance of the relationship of the variables within a university systemprovide a deeper understanding on how strategic HRM practices can contribute significantly to the achievement of competitive advantage that is sustainable within a university system, and they also show the assessment of ideas around academic restrictions. Consistent with RBV theory, the achievement of SCA requires the support of strategic HRM practices through human expertise development with core values of an organization [6]. In the same vein, a behavioral perspective suggests that different behaviors are significant for an organization to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage [11].

Strategic HRM is found to have a direct and positive influence on the achievement of sustainable competitive advantages. Our results were in agreement with some similar previous studies and found that sustainable competitive advantages could be achieved in an academic environment. However, there is a need for academic institutions to ensure that the strategic policy is put in place to see how the human resources could be managed and integrated with other intangible components of human resources [1]. Our results corroborated similar previous studies, though not in an academic environment, but they found a significance influence of HRM practices on SCA [16,17,18]. Our findings show that the effect size of strategic HRM practices on sustainable competitive advantages is weak. Thus, Iraq universities should keep improving their HRM strategy so as to keep up with the challenges of dynamic business environments.

Findings from our study also indicate that strategic HRM practices will influence positively human capital development and employee commitment. In agreement with previous studies, Emeagwal and Ogbonmwan [1] in their study found similar results in an academic environment, that employee commitment and developing human capital are influenced by the HRM practices deployed by an academic institution. In addition, the study of Alnidawi et al. [57] establishedthat an employee’s engagement in training will be through the HRM system put in place by the organization. Our study, thus, suggests that the Iraq universities should place a greater premium on human resources management of their organizations, and these will enhance human capital development by enabling the employees to develop tacit knowledge that will be difficult for competitors to imitate. Moreover, efficient management of human resources will enhance employee engagement, which will make them see themselves as part of the organization; in turn, this will boost their morale, and they will be more committed to the organization. Moreover, the findings further reveal that the effect size of strategic HRM is found to be moderate on human capital development, while it was found to be weak on employee commitment. This implies that the management of Iraqi universities should endeavor to improve on some components of human resource management that will enable employees to be more committed to their university.

The direct influence of both human capital development and the commitment of the employees on SCA were evaluated. The findings reveal that both variables had a significant and positive influence on SCA. Our findings corroborated some previous studies that established the significance of human capital development on SCA [1]. Aryanto et al. [30] did a similar study and employed some aspect of HRM practices, like HR orientation, work–life balance, and high working performance, to measure HRM. A relationship was established between HRM and organizational performance, which has the potential of achieving SCA. Moreover, the direct and positive influence of employee commitment on SCA was also established by Zehir et al. [66]. The findings of Sanches et al. [47] emphasized that the significance of HRM in human capital development, which could lead to SCA, should not be ignored. Findings of Nico et al. [52] concluded that human capital is a valuable asset to organizational performance. These corroborated with our findings. Though, Emeagwal and Ogbonmwan [1] found a positive and significant influence of human capital development on sustainability of the competitive advantages achieved by the organization in a similar study, which was in contrast to our findings. In addition, the effect size of both human capital development and employee commitment on sustainable competitive advantages was found to be weak. The implication of these findings for university management in Iraq is to pay more attention to human capital development by involving the employees in more training to enhance their competency. These will improve the chances of the university to have tacit knowledge that will place them in an advantageous position above other competitors. Moreover, employee commitment should be given adequate attention. It is apparent from our findings that human capital development and the commitment of employees to their organization will play prominent roles in how the universities in Iraq will achieve competitive advantages that are sustainable.

Findings from our study contribute significantly to the literature on strategic HRM practices and sustainability of competitive advantages, and they establish the partial mediating role of both human capital development and employee commitment, which were found to be positive and statistically significant. The implication of our findings is for university management in Iraq to change their culture from being nonprofit to profit-making organizations. The dynamism of the business environment, international competition, and the changes in the labor market require the universities to also operate like other organizations so that the achievement of sustainable competitive advantages will be feasible.

An interesting finding from our study is the significance of the type of institution as a control variable. It is an indication that the private and public universities are operating on different structures, and this will go a long way in determining how universities in Iraq will achieve sustainable competitive advantages over their competitors. Similarly, gender was found to have a negative and significance influence as a control variable on sustainable competitive advantages.

In conclusion, findings from our study contribute to human capital development, employment, and sustainable competitive advantages literature. It also presents insight into the management of academic institutions in Iraq. Further contribution to employee commitment to sustainable competitive advantage achievement was argued in our study. Iraqi university management should identify some areas in human resources management that need to be enhanced so as to increase its emphasis on both human capital development and employee commitment. Also, as suggested by Pausits and Pellert [22], universities must accept changes in their culture, like other business organizations, and then introduce strategic HRM practices, and it must be effectively applied and practiced.

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

This study acknowledged a considerable boundary restriction in its explanation; thus, there is justification for further studies to be carried out. Our study is similar to some other social science studies that are cross-sectional in design, and, as such, it is open for further causality examination. It is assumed in the relevant literature that strategic HRM practices significantly impact SCA through the employee’s skills, knowledge, capacity, and his/her attitudes and behaviors towards the organization. Nonetheless, the relationship between strategic HRM practices and SCA could be mediated by human capital development. Our research provides an innovative perspective on this relation by empirically examining the mediating role of human capital development and employee commitment in the relationship between strategic HRM practices and sustainable competitive advantages in a university system, most especially in Iraq. In addition, the significance of the types of university (private/public) was established in our research. Further study can subsequently examine the relationship between strategic HRM practices and organizational outcomes through the mediating influence of human capital development and employee commitment in a university system. Moreover, a comparative study on the relationship between public and private universities will contribute to the literature on this subject matter. Future research on the achievement of sustainable competitive advantages in the academic environment through strategic HRM practices should include other constructs, like innovations and technology, which will expand literature on sustainable competitive advantage studies in an academic environment.

Author Contributions

The article was conceptualized and the methodology was designed by both H.H.H. and T.A. Data collection and analysis were done by H.H.H., while the results validation was carried out by T.A. The manuscript was drafted by H.H.H. with the support of T.A. for the editing and proofreading.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest is declared

Appendix A

Table A1.

Construct measurement items

Table A1.

Construct measurement items

| Variable | Indicator | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Human Resource Management Practice (SHRMP) | SHRMP1: Employee selection is taken very seriously by this university | Aryanto, Fontana & Afiff (2015) |

| SHRMP2: Employee selection places priority on the candidate’s potential to learn | Aryanto, Fontana & Afiff (2015) | |

| SHRMP3: Employee selection emphasizes capacity to perform well right away | Emeagwal & Ogbonmwan (2018) | |

| SHRMP4: Employees in this university have clear career paths | Emeagwal & Ogbonmwan (2018) | |

| SHRMP5: The training programs emphasize on-the-job experiences | Sahar & Gregar (2012) | |

| SHRMP6: Performance appraisals emphasize development of abilities/skills | Zehir et al., (2016) | |

| Human Capital Development (HCD) | HCD1: The employees working in this university are highly skilled | Kadir et al., (2018) |

| HCD2: The employees working in this university are considered the best | Mahdi, Nassar & Almsafir (2019) | |

| HCD3: The employees in the university are encouraged to be creative | Sanches, Marin & Morales (2015) | |

| HCD4: The employees working in the university are experts in their jobs | Todericiu & Stanit (2015) | |

| Employee Commitment (EC) | EC1: I am committed to this university | Emeagwal & Ogbonmwan (2018) |

| EC2: I really care about the future of this university | Emeagwal & Ogbonmwan (2018) | |

| EC3: I find my values and the university’s values very similar | Zehir et al., (2016) | |

| EC4: I really feel as if this university’s problems are my own | Zehir et al., (2016) | |

| Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) | SCA1: Our university employees are highly creative and innovative | Emeagwal & Ogbonmwan (2018) |

| SCA2: Our university employees are highly involved and flexible to change | Mahdi, Nassar & Almsafir (2019) | |

| SCA3: Our university employees more concern for quality and result | Kuncoro & Suriani (2018) |

References

- Emeagwal, L.; Ogbonmwan, K.O. Mapping the perceived role of strategic human resource management practices in sustainable competitive advantage. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, J.W.; Ismail, H.B. Sustainable competitive advantage through information technology competence: Resource-based view on small and medium enterprises. Communications IBIMA 2008, 1, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Pfeffer, J. Hidden Value: How Great Companies Achieve Extraordinary Results with Ordinary People; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, N.; Gregar, A. Human resource management: As a source of sustained competitive advantage of the firms. Int. Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, G.C.; Virick, N.; Wright, P.M. Alternative theoretical perspectives for SHRM: Progress, problems and prospects. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management; Wright, P.M., Dyer, L., Boudrean, J., Milkovich, G., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1999; pp. 92–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fındıklı, M.A.; Yozgat, U.; Rofcanin, Y. Examining organizational innovation and knowledge management capacity the central role of strategic human resources practices (SHRPs). Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 181, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, C.R. Strategic Human Resource Management: A General Managerial Approach, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.C.; Wang, C.H. Clarifying the effect of intellectual capital on performance: The mediating role of dynamic capability. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnham, D. Human Resource Management in Context: Strategy, Insights and Solutions, 3rd ed.; CIPD: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; Nishii, L.H. Strategic HRM and organizational behavior: Integrating multiple levels of analysis. In Human Resource Management and Performance: Progress and Prospects; Guest, D., Paauwe, J., Wright, P., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Björkman, I.; Xiucheng, F. Human resource management and the performance of Western firms in China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 835–864. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.A.; Huang, T.C. Relationship between strategic human resource management and firm performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2005, 26, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Personnel and HRM: Can you tell the difference? Pers. Manag. 1989, 21, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, R.S.; Jackson, S.E. Organizational strategy and organization level as determinants of human resource management practices. Hum. Resour. Plan. 1987, 10, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi, O.R.; Almsafir, M.K. The role of strategic leadership in building sustainable competitive advantage in the academic environment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 129, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, O.R.; Nassar, I.A.; Almsafir, M.K. Knowledge management processes and sustainable competitive advantage: An empirical examination in private universities. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.; Palfrayman, D. The State of UK Higher Education. Managing Change and Diversity; SRHE/Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taka, M. Paths of private higher education in Iraq for the next five years (2010–2015). J. Baghdad Coll. Econ. Sci. Univ. 2010, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M. Shared governance in the modern university. High. Educ. Q. 2013, 67, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausits, A.; Pellert, A. Higher Education Management and Development in Central, Southern and Eastern Europe; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2007; pp. 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk, S.; Teelken, C.; Eisinga, R.; Doorewaard, H. An international comparison of the effects of HRM practices and organizational commitment on quality of job performances among European university employees. High. Educ. Policy 2008, 21, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlehurst, R. Changing internal governance: Are leadership roles and management structures in United Kingdom universities fit for future? High. Educ. Q. 2013, 67, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.; Lumpkin, G. Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflection on a needed construct. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratono, A.H.; Darmasetiawan, N.K.; Yudiarso, A.; Jeong, B.G. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through green entrepreneurial orientation and market orientation: The role of inter-organizational learning. Bottom Line 2019, 32, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirisu, I.; Joy Iyiola, O.; Ibidunni, S.O. Product differentiation: A tool of competitive advantage and optimal organizational performance (a study of Unilever Nigeria PLC). Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 9, 258–281. [Google Scholar]

- Zaini, A.; Hadiwidjojo, D.; Rohman, F.; Maskie, G. Effect of competitive advantage as a mediator variable of entrepreneurship orientation to marketing performance. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, S. A resource-based framework for strategically managing identity. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2019, 32, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryanto, R.; Fontana, A.; Afiff, A.Z. Strategic human resource management, innovation capability and performance: An empirical study in Indonesia software industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macher, J.T.; Mowery, D.C. Measuring dynamic capabilities: Practices and performance in semiconductor manufacturing. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, S41–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, S.A.; Youndt, M.A.; Wright, P.M. Establishing a framework for research in strategic human resource management: Merging resource theory and organizational learning. In Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 1996; Volume 14, pp. 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, E.; Monks, K. Human resource practices and commitment to change: An employee-level analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2008, 18, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E.; Michie, J.; Conway, N.; Sheehan, M. Human resource management and corporate performance in the UK. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2003, 41, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.L.P.; Nguyen, C.N.; Adhikari, R.; Miles, M.P.; Bonney, L. Exploring market orientation, innovation, and financial performance in agricultural value chains in emerging economies. J. Innov. Knowl. 2018, 3, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Prieto, I. Dynamic capabilities and knowledge management: An integrative role for learning? Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamish, G.H.E. SHRM best-practices & sustainable competitive advantage. Resour. Based View 2003, 1, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pandza, K.; Thorpe, R. Creative search and strategic sense-making: Missing dimensions in the concept of dynamic capabilities. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, S118–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aveni, R.A.; Dagnino, G.B.; Smith, K. The age of temporary competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, R.; Ruefli, T.W. Sustained competitive advantage: Temporal dynamics and the incidence and persistence of superior economic performance. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-F.; Dyerson, R.; Wu, L.-Y.; Harindranath, G. From temporary competitive advantage to sustainable competitive advantage. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 617–636. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, M.; Franklin, A.; Martinette, L. Building a sustainable competitive advantage. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 8, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntjoroadi, N.; Safitri, N. Analisis strategi bersaing dalam persaingan usaha penerbangan komersial, bisnis dan birokrasi. Bisnis Birokrasi J. 2014, 16, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human resources and the resource-based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allui, A.; Sahni, J. Strategic human resource management in higher education institutions: Empirical evidence from Saudi. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Jiang, K. An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.A.; Marín, G.S.; Morales, A.M. The mediating effect of strategic human resource practices on knowledge management and firm performance. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2015, 24, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J.; Clark, K.D. Strategic human resource practices, top management team social networks, and firm performance: The role of human resource in creating organizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 740–751. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Takeuchi, R.; Lepak, D.P. Where do we go from here? New perspectives on the black box in strategic human resource management research. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 1448–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.; Hu, J.; Baer, J. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analysis investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A. Measuring population happiness to inform public policy. In Proceedings of the 3rd OECD World Forum on ‘Statistics, Knowledge and Policy’ Charting Progress, Building Visions, Improving Life, Busan, Korea, 27–30 October 2009; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nico, C.; Paltingca, I.; Acosta, C.; Eduardo, P. Malagapo towards valuable source of sustainable competitive advantage in oil & gas sector through strategic human capital management. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon, J.M.; Roper, A.; Doherty, L. Strategic human resource management: Insights from the international hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 47, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youndt, M.A.; Snell, S.A. Human resource configurations, intellectual capital and organizational performance. J. Manag. Issues 2004, 16, 337–360. [Google Scholar]

- Garavan, T.N.; Morley, M.; Gunnigle, P.; Collins, E. Human capital accumulation: The role of human resource development. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2001, 25, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.; Vandenberg, R. Longitudinal research: The theory, design and analysis of change. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnidawi, A.A.B.; Alshemery, A.S.H.; Abdulrahman, M. Competitive advantage based on human capital and its impact on organizational sustainability: Applied study in Jordanian telecommunications sector. J. Mgmt. Sustain. 2017, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chaudhry, N.I.; Roomi, M.A. Accounting for the development of human capital in manufacturing organizations: A study of the Pakistani textile sector. J. Hum. Resour. Costing Account. 2010, 14, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar]

- Todericiu, R.; Stăniţ, A. Intellectual capital—The key for sustainable competitive advantage for the SME’s sector. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 27, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.R.A.; Aminallah, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Sulaiman, J.; Yusoff, M.F.M.; Idris, M.M.; Malek, Z.A. The influence of intellectual capital and corporate entrepreneurship towards small and medium enterprises’ (SMEs) sustainable competitive advantage: building a conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the 2nd Advances in Business Research International Conference; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, S.G.; Dajani, D.; Hasan, Y. The impact of intellectual capital on the competitive advantage: Applied study in Jordanian telecommunication companies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, M.; Jammu, M.A.; de Pablos, P.O. Intellectual capital and performance of electrical and electronics SMEs in Malaysia. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2015, 12, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, M.; Bontis, N.; Shaari, J.A.N.B.; Isa, A.H.M. Intellectual capital in small and medium enterprises in Pakistan. J. Intellect. Cap. 2015, 16, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, M.; Noor, W.S.; Isa, M.F.; Salleh, S.S. Developing human capital for sustainable competitive advantage: The roles of organizational culture and high performance work system. Int. J. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 10, 655–673. [Google Scholar]

- Zehir, C.; Gurol, Y.; Karaboga, T.; Kole, M. Strategic human resource management and firm performance: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, S.M. The model of human capital and knowledge sharing towards sustainable competitive advantages. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2015, 13, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, J. A critical assessment of the high-performance paradigm. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2004, 42, 349–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthuma, R.A.; Campion, M.C.; Masimova, M.; Campion, M.A. A high performance work practices taxonomy integrating the literature and directing future research. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1184–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, M.K.; Wali, M.F.I.; Islam, M.S. Strategic human resource management practices and its impact on sustainable competitive advantage: A comparative study between western and Bangladeshi local firms. IJABM 2013, 1, 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D.; Ostroff, C. Understanding, HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Macky, K.; Boxall, P. The relationship between high-performance work practices and employee attitudes: An investigation of additive and interaction effects. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 537–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K. Latent variables and indices: Herman wold’s basic design and partial least squares. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods, and Applications; Vinzi, V.E., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, S. “Haters gonna hate”: PLS and information systems research. DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2018, 49, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Ira, H.B. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; David, F.L. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Christian, M.R.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Savalei, V. Bootstrapping Confidence intervals for fit indexes in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2016, 23, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias: A full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).