Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics: Making a Link

Abstract

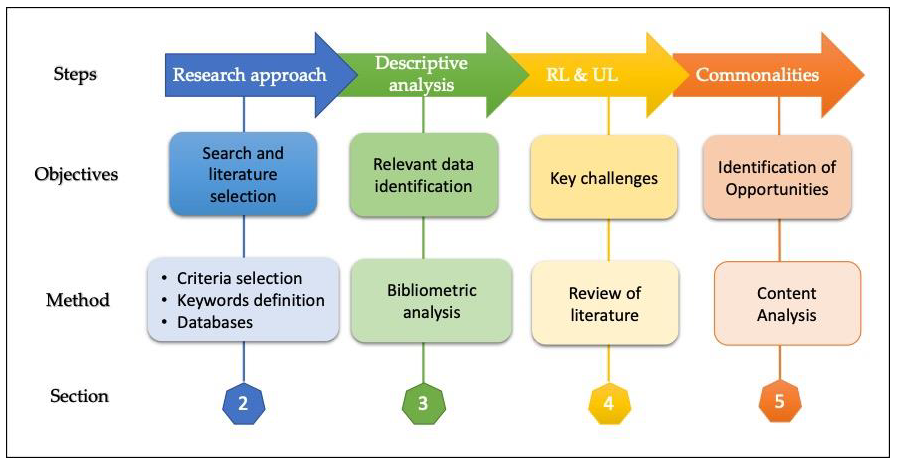

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics

3.1. Reverse Logistics

3.2. Urban Logistics

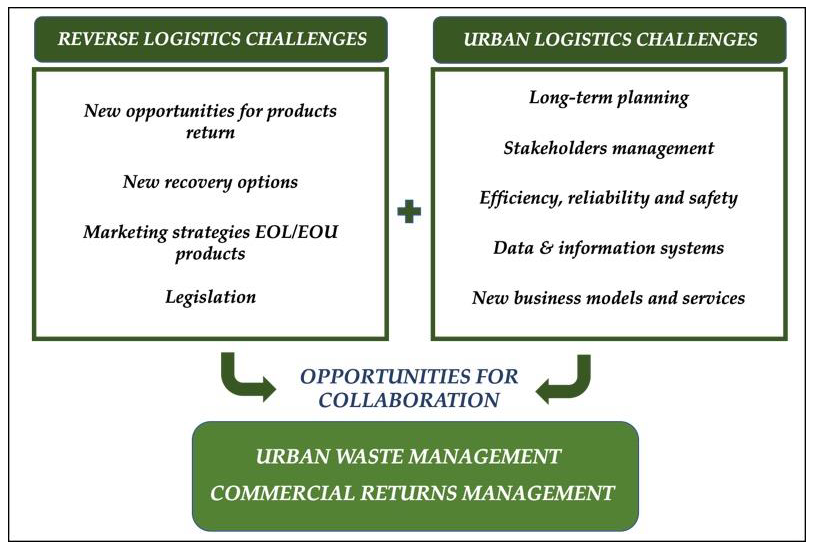

4. Areas of Collaboration Between Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics

4.1. Urban Waste Management

4.2. Management of Commercial Returns

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flapper, S.D.P.; Van Nunen, J.A.E.E.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Introduction. In Managing Closed-Loop Supply Chains; Flapper, S.D.P., Van Nunen, J.A.E.E., Van Wassenhove, L.N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-3-540-27251-9. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, S.; Singh, R.K.; Murtaza, Q. A literature review and perspectives in reverse logistics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 97, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flapper, S.D.P.; Gayon, J.P.; Vercraene, S. Control of a production-inventory system with returns under imperfect advance return information. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 218, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Soleimani, H.; Kannan, D. Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain: A comprehensive review to explore the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Bouzon, M. From literature review to a multi-perspective framework for reverse logistics barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Evangelinos, K.I.; Allan, S. A reverse logistics social responsibility evaluation framework based on a triple bottom line approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Chen, H.; Rogers, D.L.; Ellram, L.M.; Grawe, S.J. A bibliometric analysis of reverse logistics research (1992–2015) and apportunities for future research. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 666–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huscroft, J.R.; Hazen, B.T.; Hall, D.J.; Skipper, J.B.; Hanna, J.B. Reverse logistics: Past research, current management issues, and future directions. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2013, 24, 304–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. The evolution of closed-loop supply chain research. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.T. Strategic reverse logistics disposition decisions: From theory to practice. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2011, 10, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.C. Closed-loop supply chains: A critical review, and future research. Decis. Sci. 2013, 44, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.; Goel, L.; Francisco, K.; Stock, J. An analysis of supply chain management research by topic. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 23, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverse Logistics Association. Logistics Management. Shippers No Longer Reactive When It Comes to Reverse Logistics. Available online: https://www.logisticsmgmt.com/article/shippers_no_longer_reactive_when_it_comes_to_reverse_logistics (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Rubio, S.; Jiménez-Parra, B. La logística inversa en las ciudades del futuro. Econ. Ind. 2016, 400, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Crainic, T.G.; Ricciardi, N.; Storchi, G. Models for evaluating and planning city logistics systems. Transp. Sci. 2009, 43, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunder, T.H.; Aditjandra, P.; Zahurum, I.D.M.; Tumasz, M.R.; Carnaby, B. Urban freight distribution. In Handbook on Transport and Urban Planning in the Developed World; Bliemer, M.C.J., Mulley, C., Moutou, C.J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 106–129. ISBN 978-0-85793-725-4. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, G.; Kang, S.; Yuang, Q. Using proxies to describe the metropolitan freight landscape. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALICE/ERTRAC. Urban Freight Research Roadmap; Report from ALICE/ERTRAC Urban Mobility Working Group; ERTRAC: Bruselas, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.; Meyer, D. City Logistics Research. A Transatlantic Perspective; Working Knowledge Rapporteurs: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Savelsbergh, M.; Van Woensel, T. City logistics: Challenges and opportunities. Transp. Sci. 2016, 50, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, E.; Thompson, R.G.; Yamada, T. Recent trends and innovations in modelling city logistics. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Delivering Goods. 21st Century Challenges to Urban Goods Transport; OECD: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, S.; Chamorro, A.; Miranda, F.J. Characteristics of the research on reverse logistics (1995–2005). Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 1099–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, A.; Pinto, R.; Golini, R. Research in urban logistics: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrkal, K.; Larsen, A.; Ropke, S. The waste collection vehicle routing problem with time windows in a city logistics context. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 39, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.; Muñoz, J.C.; Giesen, R. How many urban recycling centers do we need and where? A continuum approximation approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Salas, Y.; Sarache, W.; Überwimmer, M. Fleet size optimization in the discarded tire collection process. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2017, 24, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, J.; Iwan, S.; Korczak, J. Usability of the parcel lockers from the customer perspective. The research in Polish cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 16, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhaief, N.; Bistorin, O.; Rezg, N. A modelling approach for city locating logistic platforms based on combined forward and reverse flows. IFAC PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 11701–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V.; Le Pira, M. Gamification design to foster stakeholder engagement and behavior change: An application to urban freight transport. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, R.A. Management Model for Closed-Loop Supply Chains of Reusable Articles. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Brito, M.P.; Dekker, R. A framework for reverse logistics. In Reverse Logistics. Quantitative Models for Closed-Loop Supply Chains; Dekker, R., Fleishchmann, M., Inderfurth, K., Van Wassenhove, L.N., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 3–28. ISBN 978-3-540-24803-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, I. The concept of reverse logistics. A review of the literature. Reverse Logist. Digit. Mag. 2003, 58, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, D.S.; Tibben-Lembke, R.S. Going Backwards: Reverse Logistics Trends and Practices, 1st ed.; Council of Reverse Logistics: Reno, NV, USA, 1999; pp. 1–280. ISBN 978-09-6746-190-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, S.; Jiménez-Parra, B. Reverse logistics: Concept, evolution and marketing challenges. In Optimization and Decision Support Systems for Supply Chains; Paula, B.-P.A., Corominas, A., Eds.; Springer: Dortmund, Germany, 2017; pp. 41–61. ISBN 978-3-319-42421-7. [Google Scholar]

- Guiltinan, J.P.; Nwokoye, N.G. Reverse channels for recycling: An analysis for alternatives and public policy implications. In New Marketing for Social and Economic Progress. Combined Proceedings; Curhan, R.G., Ed.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ginter, P.M.; Starling, J.M. Reverse distribution channels for recycling. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1978, 20, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlen, T.L.; Farris, M.T. Reverse logistics in plastic recycling. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. 1992, 22, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.R. Reverse Logistics, 1st ed.; Council of Logistics Management: Oak Brook, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kopicky, R.J.; Berg, M.J.; Legg, L.; Dasappa, V.; Maggioni, C. Reuse and Recycling: Reverse Logistics Opportunities, 1st ed.; Council of Logistics Management: Oak Brook, IL, USA, 1993; pp. 1–324. ISBN 978-99-9559-383-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, M.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; Dekker, R.; van der Laan, E.; van Nunen, J.A.E.E.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Quantitative models for reverse logistics: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1997, 103, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Souza, G.C. Closed-Loop Supply Chains: New Developments to Improve the Sustainability of Business Practices, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Ratón, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 1–257. ISBN 978-14-2009-525-8. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, V.V.; Atasu, A.; van Ittersum, K. Remanufacturing, third-party competition, and consumers’ perceived value of new products. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stindt, D.; Sahamie, R. Review of research on closed loop supply chain management in the process industry. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2014, 26, 268–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, A.; Mateo, M.; Ribas, I.; Rubio, S. Methodological elements of supply chain design. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5017–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoniam, R.; Huisingh, D.; Chinnam, R.B. Remanufacturing for the automotive aftermarket-strategic factors: Literature review and future research needs. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Circular Economy. Implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan; Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Fenton, R.W. Stewardship for packaging and packaging waste: Key policy elements for sustainability. Can. Public Adm. 1997, 40, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, S.; Ramos, T.R.P.; Leitão, M.M.R.; Barbosa-Povoa, A.P. Effectiveness of extended producer responsibility policies implementation: The case of Portuguese and Spanish packaging waste systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Ruiz-Roqueñi, M. Factores determinantes de la integración de la variable medio ambiente en los planteamientos de la economía de la empresa y el marketing. Cuad. Gest. 2002, 1, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel, S.; Mutha, A. Perspectives in reverse logistics: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahinski, C.; Kocabasoglu, C. Empirical research opportunities in reverse supply chains. Omega 2006, 34, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Parra, B.; Rubio, S.; Vicente-Molina, M.A. Key drivers in the behavior of potential consumers of remanufactured products: A study on laptops in Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramoniam, R.; Huisingh, D.; Chinnam, R.B.; Subramoniam, S. Remanufacturing decision-making framework (RDMF): Research validation using the analytical hierarchical process. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, M. Extended Producer Responsibility and Product Design: Economic Theory and Selected Case Studies; Disussion Paper 06–08; OECD: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Organization World Urbanization Prospects. The 2018 Revision (Key Facts); UN: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, F.; Comi, A. A classification of city logistics measures and connected impacts. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 6355–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Progress of EU Transport Sector Towards Its Environment and Climate Objectives. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/transport/term/term-briefing-2018 (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- WHO. Making the (Transport, Health and Environment) Link; Transport, Health and Environment Pan-European Programme and Sustainable Development Goals Report; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Together Towards Competitive and Resource-Efficient Urban Mobility. A Call to Action on Urban Logistics; Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, G.; Pastor, R. Metodología para la definición de un sistema logístico que trate de lograr una distribución urbana de mercancías eficiente. Dir. Organ. 2009, 37, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, W.J.; Bell, J.E.; Autry, C.W.; Cherry, C.R. Urban logistics: Establishing key concepts and building a conceptual framework for future research. Transp. J. 2017, 56, 357–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dablanc, L.; Browne, M. Introduction to special section on logistics sprawl. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín-Veras, J.; Leal, J.A.; Sánchez-Díaz, I.; Browne, M.; Wojtowicz, J. State of the art and practice of urban freight management. Part I: Infrastructure, vehicle-related, and traffic operations. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín-Veras, J.; Leal, J.A.; Sánchez-Díaz, I.; Browne, M.; Wojtowicz, J. State of the art and practice of urban freight management. Part II: Financial approaches, logistics, and demand management. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharis, C.; Keseru, I. Rethinking mobility for human city. Transpor. Rev. 2018, 38, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, M.D.; Serna, C.A.; Álvarez, K.C. Collaborative autonomous systems in models of urban logistics. DYNA 2012, 79, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Delaitre, L.; Molet, H.; Awasthi, A.; Breuil, D. Characterising urban freight solutions for medium sized cities. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2009, 2, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicilia, J.A.; Larrode, E.; Royo, B.; Escuín, D. Sistema inteligente de planificación de rutas para la distribución de mercancías. DYNA Ingeniería e Industria 2013, 88, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adtijandra, P.T.; Zunder, T.H. Developing a multi-dimensional policy parametric typology for city logistics. In City Logistics 2: Modelling and Planning Initiatives; Taniguchi, E., Thompson, R.G., Eds.; ISTE Ltd.: Washington, DC, USA; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 141–163. ISBN 978-1-119-49511-6. [Google Scholar]

- Clott, C.; Hartman, B.C. Supply chain integration, landside operations and port accessibility in metropolitan Chicago. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 51, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrellón-Torres, J.P.; Talero-Chaparro, J.S.; Manosalva-Barrera, N.E.; Torres-Acosta, J.H.; Adarme-Jaimes, W. Information technology in city logistics: A decision support system for off-hour delivery programs. In Exploring Intelligent Decision Support Systems. Current State and New Trends. Studies in Computational Intelligence; Valencia-García, R., Paredes-Valverde, M.A., Salas-Zárate, M.P., Alor-Hernández, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 221–238. ISBN 978-3-319-74001-0. [Google Scholar]

- Merchán, D.E.; Blanco, E.E.; Bateman, A.H. Urban metrics for urban logistics: Building an atlas for urban freight policy makers. In Proceedings of the Computers in Urban Planning and Urban Management (CUPUM 2015), Cambrige, MA, USA, 7–10 July 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, J.; Lone, S.; Chen, J.; Koene, M. Global Ecommerce Report 2017; Ecommerce Foundation: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, X.; Bloemhof, J.M.; Ramos, T.R.P.; Barbosa-Povoa, A.P.; Wong, C.Y.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J. Research challenges in municipal solid waste logistics management. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing, X.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J. Sustainable reverse logistics network design for household plastic waste. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2014, 26, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliën, J.; De Boeck, L.; Van Ackere, J. Municipal solid waste collection and management problems: A literature review. Transp. Sci. 2014, 48, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikopoulos, C.; Tagaras, G. Reverse supply chains: Effects of collection network and returns classification on profitability. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 246, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide, V.; Daniel, R.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Business Aspects of Closed Loop Supply Chains, 1st ed.; Carnegie Mellon University Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–381. ISBN 978-08-8748-402-5. [Google Scholar]

- Muñuzuri, J.; Cortés, P.; Guadix, J.; Onieva, L. City logistics in Spain: Why it might never work. Cities 2012, 29, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Study on Urban Freight Transport; Final Report by MDS Transmodal Limited in association with CTL; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wall Street Journal. The Rampant Returns Plague E-Retailers. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/rampant-returns-plague-eretailers-1387752786 (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Forbes. Is There a Real State Solution to E-Commerce’s Returns Problem? Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bisnow/2017/07/26/is-there-a-real-estate-solution-to-e-commerces-returns-problem/#4826fd806a7b (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Forbes. E-Commerce Is Boosting This Hidden Part of the Retail Market. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/elyrazin/2017/11/22/e-commerce-is-boosting-this-hidden-part-of-the-retail-market/#665a81b12de1 (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Röllecke, F.J.; Huchzermeier, A.; Schröder, D. Returning customers: The hidden strategic opportunity of returns management. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New York Times. In Season of Returning, a Start-Up Tries to Find Homes for Rejects. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/29/business/in-season-of-returning-a-start-up-tries-to-find-homes-for-the-rejects.html (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Swisslog. Returns: The Dark Side of E-Commerce: And How to Find the Light. Available online: https://www.dcvelocity.com/files/pdfs/whitepapers/forte-returns_dark_side_of_ecommerce_wp.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- UPS. UPS Pulse of the Online Shopper. Tech-Savvy Shoppers Transforming Retail; UPS White Paper: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, J.D.; Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; Souza, G.C.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Management for commercial returns. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, J.; Buckalew, L.; Chung, G. Internet of Things in Logistics: A Collaborative Report by DHL and Cisco on Implications and Use Cases for the Logistics Industry; DHL Customer Solutions & Innovation: Troisdorf, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colvero, D.A.; Gomes, A.P.D.; Tarelho, L.A.D.C.; Matos, M.A.A.D.; Santos, K.A.D. Use of a geographic information system to find areas for locating of municipal solid waste management facilities. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quak, H.J. Urban freight transport: The challenge of sustainability. In City Distribution and Urban Freight Transport: Multiple Perspectives; Macharis, C., Melo, S., Eds.; NECTAR Series on Transportation and Communication Network Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; pp. 37–55. ISBN 978-0-85793-274-7. [Google Scholar]

- Marinov, M.; Giubilei, F.; Gerhardt, M.; Özkan, T.; Stergiou, E.; Papadopol, M.; Cabecinha, L. Urban freight movement by rail. J. Trans. Lit. 2013, 7, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.A.; Maas, G.; Hogland, W. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adtijandra, P.T.; Zunder, T.H. Exploring the relationships between urban freight demand and the purchasing behaviour of a University. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2018, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Topics | Context | Methodology | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buhrkal et al. [25] | Urban waste management and Reverse supply chain design | Denmark | Waste Collection Vehicle Routing Optimization Problem | Practical implications for waste collection companies and other relevant parties are missing |

| Soto et al. [26] | Chile | Optimization problem applied to a case study | Research applied to a very particular context so it would be difficult to generalize results | |

| Costa-Salas et al. [27] | Colombia | Simulation based on a case study | Case-specific results | |

| Lemke et al. [28] | E-commerce product return | Poland | Survey | Supply perspective, a key factor in urban freight transport analysis, is not considered |

| Ndhaief et al. [29] | Reverse supply chain design | Not applied to any specific country | Location-allocation mathematical problem | Relevant factors are missed in the framework developed |

| Marcucci et al. [30] | Stakeholder engagement | Italy | Gamification | Results are highly dependent on the research context |

| Challenges | Topics | References |

|---|---|---|

| New opportunities related to the return of products and new recovery options |

| Prahinski and Kocabasoglu [52] Rogers and Tibben-Lembke [34] Rubio et al. [23] |

| Marketing strategies for recovered products |

| Ferguson and Souza [42] Guide and Van Wassenhove [9] Jiménez-Parra et al. [53] Souza [11] |

| Specific legislation on the return of products in certain contexts |

| Rubio et al. [49] Subramoniam et al. [54] Walls [55] |

| Challenges | Topics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Long-term planning of cities |

| European Commission [60] Lagorio et al. [24] Rose et al. [62] Savelsbergh and Van Woensel [20] |

| Stakeholder management and cooperation |

| Aditjandra and Zunder [70] Clott and Hartman [71] Lagorio et al. [24] Rose et al. [62] Savelsbergh and Van Woensel [20] |

| Improvement of data and information management |

| ALICE/ERTRAC [18] Castrellón-Torres et al. [72] European Commission [60] Lagorio et al. [24] Merchán et al. [73] Savelsbergh and Van Woensel [20] |

| Research on efficiency, reliability, and safety |

| ALICE/ERTRAC [18] European Commission [60] Savelsbergh and Van Woensel [20] |

| New business models and services |

| Lagorio et al. [24] Savelsbergh and Van Woensel [20] Abraham et al. [74] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio, S.; Jiménez-Parra, B.; Chamorro-Mera, A.; Miranda, F.J. Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics: Making a Link. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205684

Rubio S, Jiménez-Parra B, Chamorro-Mera A, Miranda FJ. Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics: Making a Link. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205684

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio, Sergio, Beatriz Jiménez-Parra, Antonio Chamorro-Mera, and Francisco J. Miranda. 2019. "Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics: Making a Link" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205684

APA StyleRubio, S., Jiménez-Parra, B., Chamorro-Mera, A., & Miranda, F. J. (2019). Reverse Logistics and Urban Logistics: Making a Link. Sustainability, 11(20), 5684. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205684