How DMO Can Measure the Experiences of a Large Territory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

- (a)

- investigation object: the experiences;

- (b)

- destinations;

- (c)

- platform of reviews; and

- (d)

- analysis techniques.

- historical and cultural (visit to churches, castles, monuments, museum, etc.);

- outdoor and nature (beaches, lake/sea; mountain, parks, etc.);

- sport and well-being (sailing, golf, hiking, spas, thermal baths, etc.);

- shopping and crafts;

- food and wine (tastings, cooking classes, etc.); and

- services (characteristic or unusual transport, for example steam train, etc.).

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

- the name of the experience reviewed;

- the number of reviews per experience;

- the type of experience: historical and cultural; outdoor and nature; sport and well-being; shopping and crafts; food and wine; services.

- The type of reviewing visitors: families/couples/solo/business/friends;

- the year period for which the traveller has posted a review: Mar–May/July–Aug/Sept–Nov/Dec–Feb; and

- the language used by the reviewer: Italian, English, German, Dutch, French, Russian, etc.

3.2. Sentiment Analysis

3.3. Bayesian Machine-Learning-Based Content Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

- (a)

- the selection of the experiences to be considered for the analysis;

- (b)

- the selection of the destinations to be considered for the analysis;

- (c)

- the collection of data/reviews from the TripAdvisor platform; and

- (d)

- the application of analysis techniques.

- Brescia and Hinterland Brescia: cultural destination. The city of Brescia (with its 200,000 inhabitants) and the municipalities of its hinterland. The art city of the Mille Miglia (historic classic car race on the Brescia-Rome-Brescia route) and with the largest Roman archaeological area in North Italy, now Unesco site;

- “Pianura Bresciana” (Brescian Lowland): rural destination. The lowland is one of the most important agricultural areas of Italy;

- Iseo Lake: relaxing/leisure destination. Iseo Lake is a romantic lake, with Monte Isola in the downtown, the largest island in Italy;

- Franciacorta: wine destination. The land of the prestigious Franciacorta DOCG.

- Camonica valley: sport and cultural destination. The valley of skiing and rock engravings national parks, the first Unesco site in Italy;

- Trompia valley: sport and cultural destination. The valley of mines, iron, nature and art;

- Idro Lake and Sabbia valley: sport and relaxing destination. The land of outdoor sports and Idro Lake, the highest of the Lombardy pre-alpine lakes. Peace and relaxing on the border with Trentino;

- Garda Lake: holiday destination. The largest lake in Italy, between beaches and liberty villas.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Sentiment Analysis

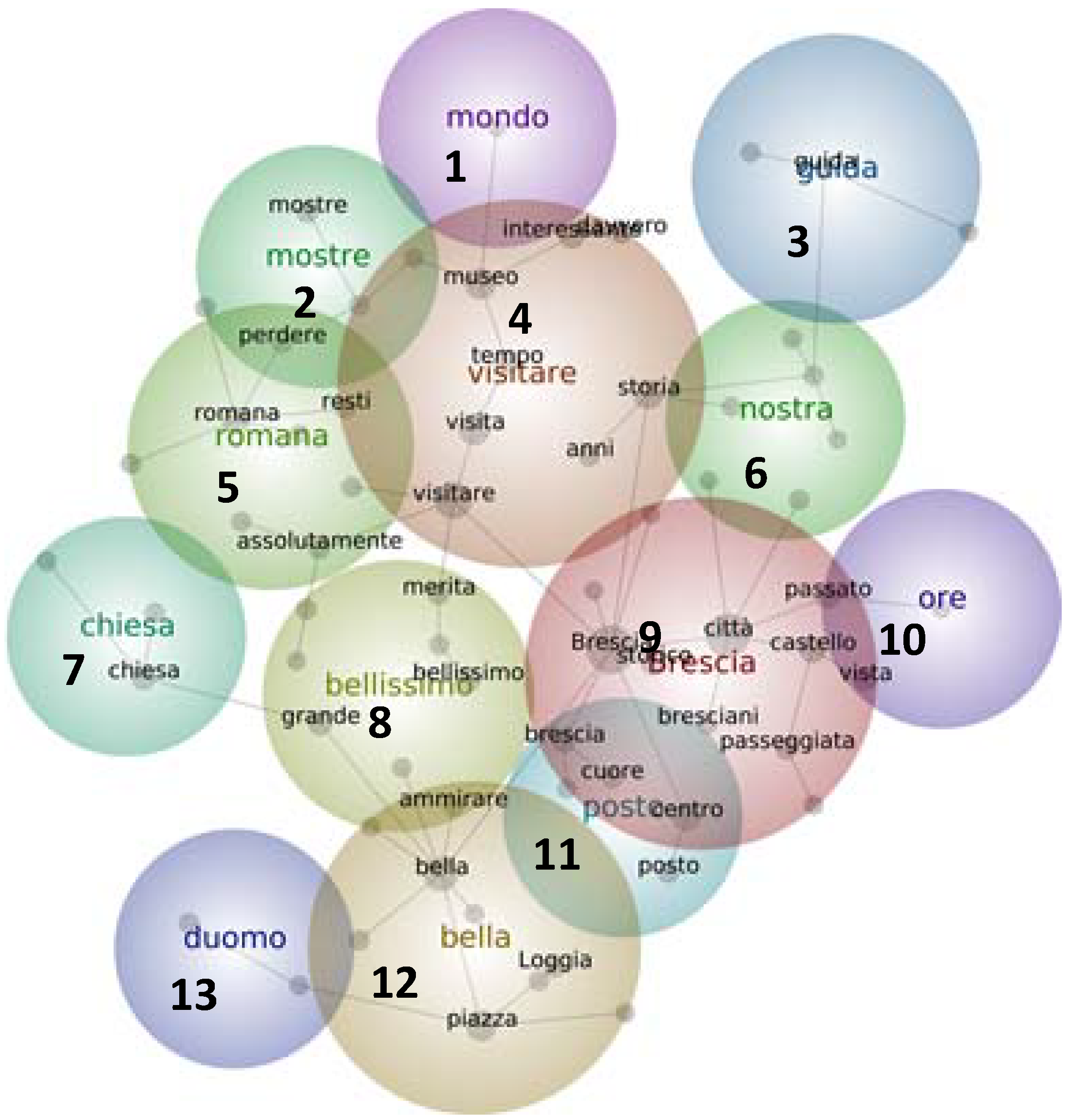

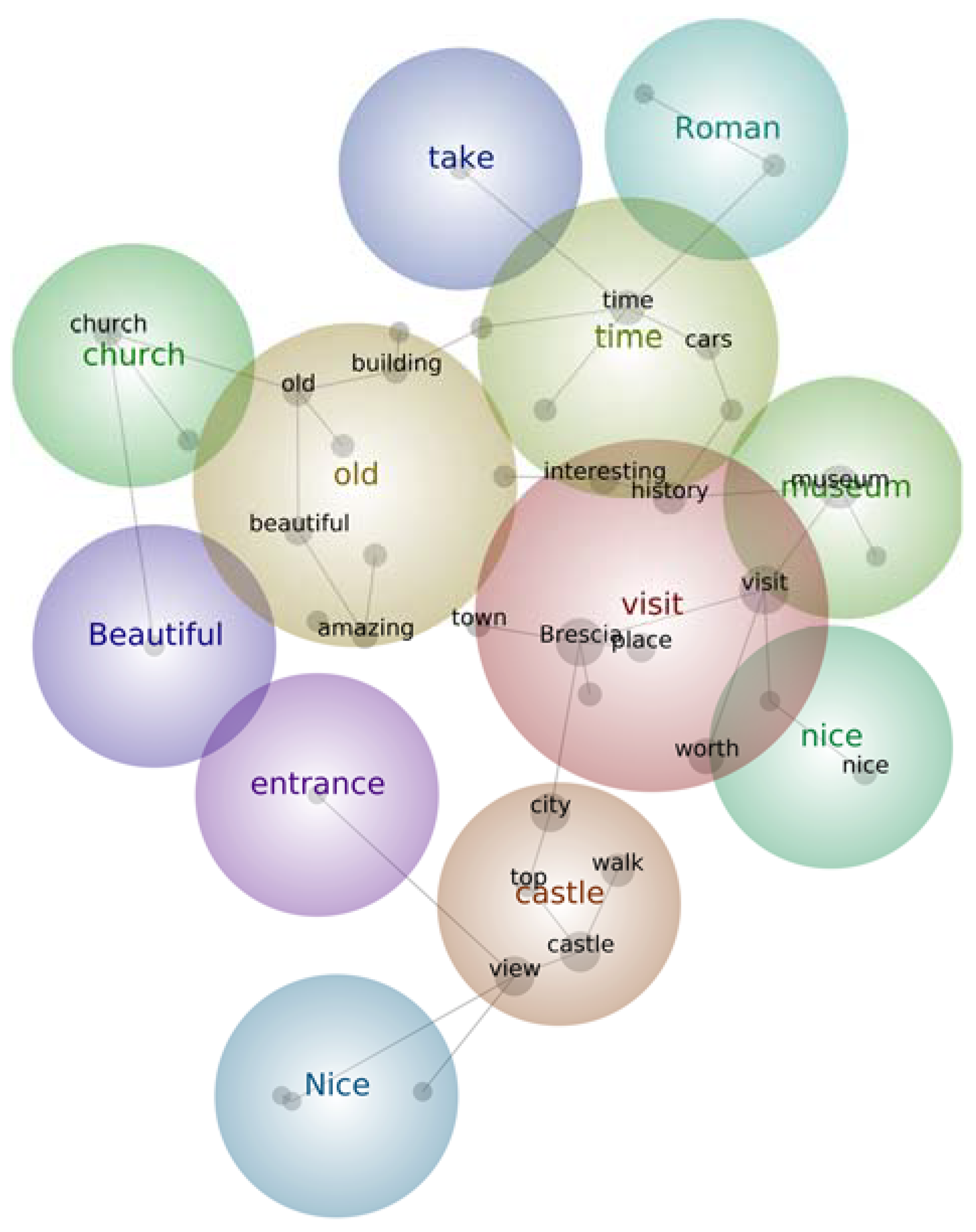

4.3. Bayesian Machine Learning-Based Content Analysis

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sparks, B.A.; Perkins, H.E.; Buckley, R. Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.; Plangger, K.; Bal, A. The new WTP: Willingness to participate. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Sharing tourism experiences: The posttrip experience. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travel Trends & Motiv, Global Findings. TripBarometer Report. 2016. Available online: www.tripadvisor.com/TripAdvisorInsights/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/TripBarometer-2016-Traveler-Trends-Motivations-Global-Findings.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Fuggle, L. The Travel and Tourism Statistics and Insights to Know about in 2016. Travel Trend Report. 2016. Available online: www.trekksoft.com (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Mauri, A.G.; Minazzi, R. Web reviews influence on expectations and purchasing intentions of hotel potential customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, R.A.; Racherla, P.; Bush, V.D. What we know and don’t know about online word-of-mouth: A review and synthesis of the literature. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroponte, N.; Maes, P. Electronic word of mouth. Wired Magazine 1996, 4, 1–2. Available online: http://archive.wired.com/wired/archive/4.10/negroponte.html (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Bilgihan, A.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Consumer perception of knowledge-sharing in travel-related online social networks. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, V. The becoming of user generated reviews: Looking at the past to understand the future of managing reputation in the travel sector. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.; Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Use of social media across the trip experience: An application of latent transition analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, I.E.; Seegers, D. Tried and tested. The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Lee, J.; Han, I. The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Electron. Comput. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Buhalis, D. A model of perceived image, memorable tourism experiences and revisit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 8, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas-Coll, S.; Palau-Saumell, R.; Matute, J.; Tárrega, S. How Do Service Quality, Experiences and Enduring Involvement Influence Tourists’ Behavior? An Empirical Study in the Picasso and Miró Museums in Barcelona. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Di Felice, M.; Mura, M. Facebook as a destination marketing tool: Evidence from Italian regional Destination Management Organizations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N. Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C. Trends in the Experience and Service Economy: The Experience Profit Cycle; London School of Economics: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Creating memorable experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 3, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, P.; Crotts, J.C. Antecedents of novelty seeking: International visitors’ propensity to experiment across Hong Kong’s culinary traditions. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.; Crouch, G. The competitiveness destination: A sustainability perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- D’Harteserre, A. Lessons in Managerial Destination Competitiveness in the case of Foxwoods Casiro Resort. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I. Modeling Destination Competitiveness: A Survey and Analysis of the Impact of Competitiveness; Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism: Gold Coast, OLD, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Franzoni, S. Measuring the sustainability performance of the tourism sector. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. Conceptualising technology enhanced destination experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. Smart technologies for personalized experiences: A case study in the hospitturnality domain. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.; Beck, J.; Him, S.; Cha, J. Identifying the Dimensions of the Experience Construct. J. Hosp. Leisure Mark. 2006, 15, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamboulis, Y.; Skayannis, P. Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Bilgihan, A. Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing: How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, and Relate to Your Company and Brands; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J. The Service Experience in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Vajic, M. The Contextual and Dialectical Nature of Experiences; Fitzsimmons, J.A., Fitzsimmons, M.J., Eds.; New Service Development: Creating Memorable Experiences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Soc. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Ryu, K.; Hussain, K. Influence of experiences on memories, satisfaction andbehavioral intentions: A study of creative tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J.; Sørensen, F. Remembered experiences and revisit intentions: A longitudinal study of safari park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.H.; Ritchie, J.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The theme parkexperience: An analysis of pleasure, arousal and satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonera, M.; Corvi, E.; Codini, A.P.; Ma, R. Does Nationality Matter in Eco-Behaviour? Sustainability 2017, 9, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, T. Indicators of tourism sustainability. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, J.F.; Ivars, J.A. Measuring sustainability in a mass tourist destination: Pressures, perceptions and policy responses in Torrevieja, Spain. J. Sustain. Tourism 2003, 11, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, V.; McCrum, G.; Blackstock, K.L.; Scott, A. Indicators and Sustainable Tourism: Literature Review; Macaulay Institute: Aberdeen, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. The development of indicators for sustainable tourism: Results of a Delphi survey of tourism researchers. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, J.; Wheeler, F.; Reeves, K.; Frost, W. Assessing the experiential value of heritage assets: A case study of a Chinese heritage precinct, bendigo, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.L.; Lu, S.J.; Guo, Y.R. Investigating the motivationeexperience relationship in a dark tourism space: A case study of the beichuan earthquake relics, China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriello, A.; Mason, P.R.; Davis, B.; Crotts, J.C. Farm tourism experiences in travel reviews: A cross-comparison of three alternative methods for data analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Wu, J.S. Understanding casino experiential attributes: An application to market positioning. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C.; Santos, C.A. Tourism, place and placelessness in the phenomenological experience of shopping malls in Seoul. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leiper, N. Tourist attraction systems. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.; Wall, G. Tourism: Economic, Physical and Social Impacts; Longman Scientific & Technica: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D. Tourism and the Autonomous Communties in Spain. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.; Rein, I. Marketing Places; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Destination benchmarking. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B.; Barrong, G.; Wood, R.C. Politics, policy and regional tourism administration: A case examination of Scottish area tourist board funding. Tour. Manag. 2011, 22, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Au, N.; Law, R. Do we believe in TripAdvisor? examining credibility perceptions and online travelers’ attitude toward using user generated content. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, D. Knowledge, economy, technology and society: The politics of discourse. Telemat. Inf. 2005, 22, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, K.; Farshid, M.; Bredican, J.; Humphrey, S. Making sense of online consumer reviews: A methodology. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 55, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.E.; Humphreys, M.S. Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behav. Res. Met. 2006, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamimaeda, N.; Izumi, N.; Hasida, K. Evaluation of participants’ contributions in knowledge creation based on semantic authoring. Learn. Org. 2007, 14, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.; Denize, S. Competing interests: The challenge to collaboration in the public sector. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Pol. 2008, 28, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Smith, A.E. Use of Automated Content Analysis Techniques for Event Image Assessment. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Pitt, L.F.; Parent, M.; Berthon, P.R. Understanding consumer conversations around ads in a Web 2.0 world. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Pitt, L.F.; Parent, M.; Berthon, P. Tracking back-talk in consumer-generated advertising: An analysis of two interpretative approaches. J. Advert. Res. 2011, 51, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Marquez, J.L.; Gonzalez-Carrasco, I.; Lopez-Cuadrado, J.L.; Ruiz-Mezcua, B. Towards a big data framework for analyzing social media content. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, F.; Vigolo, V.; Ugolini, M.M.; Baratta, R. Exploring city image: residents’ versus tourists’ perceptions. TQM J. 2018, 30, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.D.; Rossman, J.R. Creating value for participants through experience staging: Parks, recreation, and tourism in the experience industry. J. Park Recreat. Admin. 2008, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zehrer, A. Service experience and service design: Concepts and application in tourism SMEs. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2009, 19, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Xu, F. Student travel experiences: Memories and dreams. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Uncovering unconscious memories and myths for understanding international tourism behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. Destinations | No. Municipalities |

|---|---|

| 1. Brescia City and Hinterland | 10 |

| 2. Pianura Bresciana | 57 |

| 3. Iseo Lake | 8 |

| 4. Franciacorta | 19 |

| 5. Camonica Valley | 41 |

| 6. Trompia Valley | 18 |

| 7. Sabbia Valley and Idro Lake | 27 |

| 8. Garda Lake | 26 |

| Province of Brescia | 206 |

| Destinations | No. Municipalities | No. Experiences | No. Reviews at 15 June 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |||

| 1. Brescia City and Hinterland | 10 | 60 | 4727 | 18.74 |

| 2. Pianura Bresciana | 57 | 32 | 1095 | 4.34 |

| 3. Iseo Lake | 8 | 38 | 1955 | 7.75 |

| 4. Franciacorta | 19 | 52 | 1860 | 7.38 |

| 5. Camonica Valley | 41 | 57 | 1669 | 6.62 |

| 6. Trompia Valley | 18 | 11 | 133 | 0.53 |

| 7. Sabbia Valley and Idro Lake | 27 | 12 | 307 | 1.22 |

| 8. Garda Lake | 26 | 130 | 13,474 | 53.43 |

| Total | 206 | 392 | 25,220 | 100.00 |

| Type of Experience | Experiences | Reviews | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Historical and cultural | 192 | 48.98 | 14,144 | 56.08 |

| Outdoor and nature | 58 | 14.80 | 3742 | 14.84 |

| Sport and well-being | 81 | 20.66 | 5197 | 20.61 |

| Shopping and crafts | 12 | 3.06 | 886 | 3.51 |

| Food and wine | 42 | 10.71 | 938 | 3.72 |

| Services | 7 | 1.79 | 313 | 1.24 |

| Total | 392 | 100.00 | 25,220 | 100.00 |

| Experiences | No. Reviews of Experiences/Total Reviews |

|---|---|

| 1. Thermal Baths of Sirmione–SPA–Termale Aquaria | 7.74 |

| 2. Scaligera Fortress and Castle | 7.41 |

| 3. Catullo Cavern | 7.19 |

| 4. Vittoriale degli Italiani | 6.83 |

| 5. Brescia Castle | 3.22 |

| 6. Lake of Iseo | 2.99 |

| 7. Old cathedral of Brescia | 2.70 |

| 8. S. Giulia Museum | 2.44 |

| 9. Thermal Baths of Boario | 1.92 |

| 10. Outlet Village Franciacorta | 1.92 |

| No. Destinations | Excellent (%) | Very Good (%) | Average (%) | Poor (%) | Terrible (%) | No. Reviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Brescia City and Hinterland | 59.61 | 31.14 | 6.94 | 1.48 | 0.83 | 4727 |

| 2. Po Valley | 52.43 | 35.17 | 7.46 | 2.33 | 2.61 | 1072 |

| 3. Iseo Lake | 46.83 | 38.88 | 10.43 | 2.24 | 1.61 | 1610 |

| 4. Franciacorta | 42.74 | 37.99 | 12.35 | 3.91 | 3.02 | 1790 |

| 5. Camonica Valley | 53.61 | 34.42 | 7.88 | 2.71 | 1.38 | 1662 |

| 6. Trompia Valley | 62.41 | 32.33 | 3.01 | 1.50 | 0.75 | 133 |

| 7. Sabbia Valley and Idro Lake | 55.37 | 31.92 | 7.82 | 1.63 | 3.26 | 307 |

| 8. Garda Lake | 54.30 | 33.46 | 8.30 | 2.06 | 1.88 | 13,474 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franzoni, S.; Bonera, M. How DMO Can Measure the Experiences of a Large Territory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020492

Franzoni S, Bonera M. How DMO Can Measure the Experiences of a Large Territory. Sustainability. 2019; 11(2):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020492

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranzoni, Simona, and Michelle Bonera. 2019. "How DMO Can Measure the Experiences of a Large Territory" Sustainability 11, no. 2: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020492

APA StyleFranzoni, S., & Bonera, M. (2019). How DMO Can Measure the Experiences of a Large Territory. Sustainability, 11(2), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020492