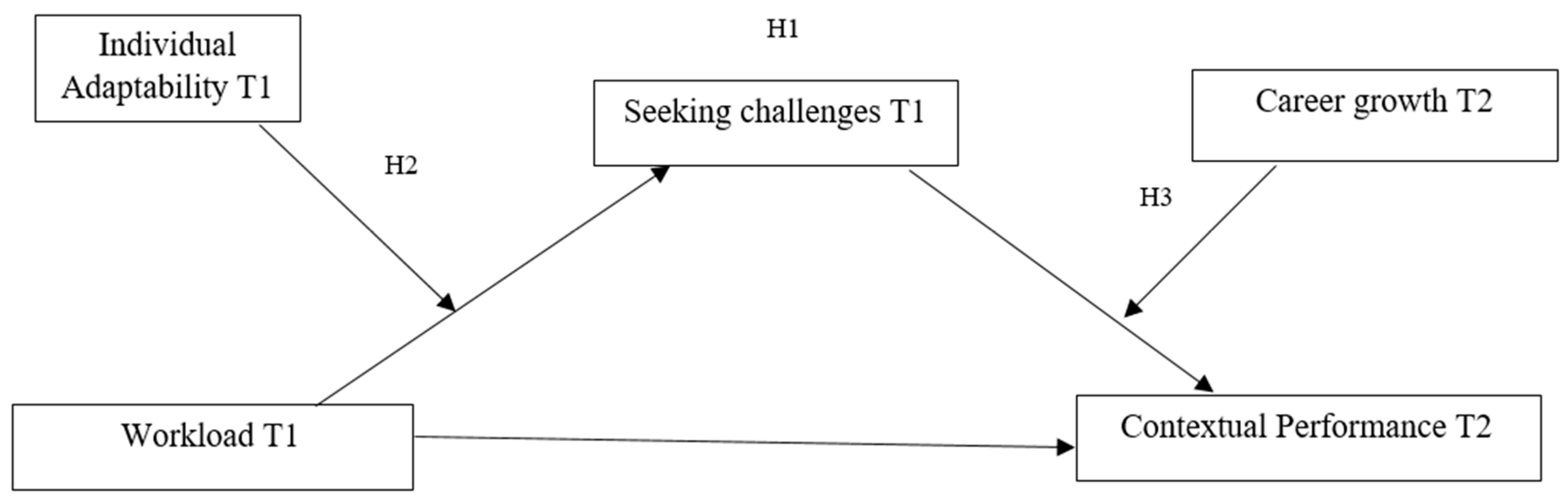

Seeking Challenges, Individual Adaptability and Career Growth in the Relationship between Workload and Contextual Performance: A Two-Wave Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Mediating Role of Seeking Challenges in the Relationship between Workload and Contextual Performance

1.2. The Moderating Role of Individual Adaptability in the Relationship between Workload and Seeking Challenges

1.3. The Moderating Role of Organizational Career Growth in the Relationship between Seeking Challenges and Contextual Performance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Ethical Aspects

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

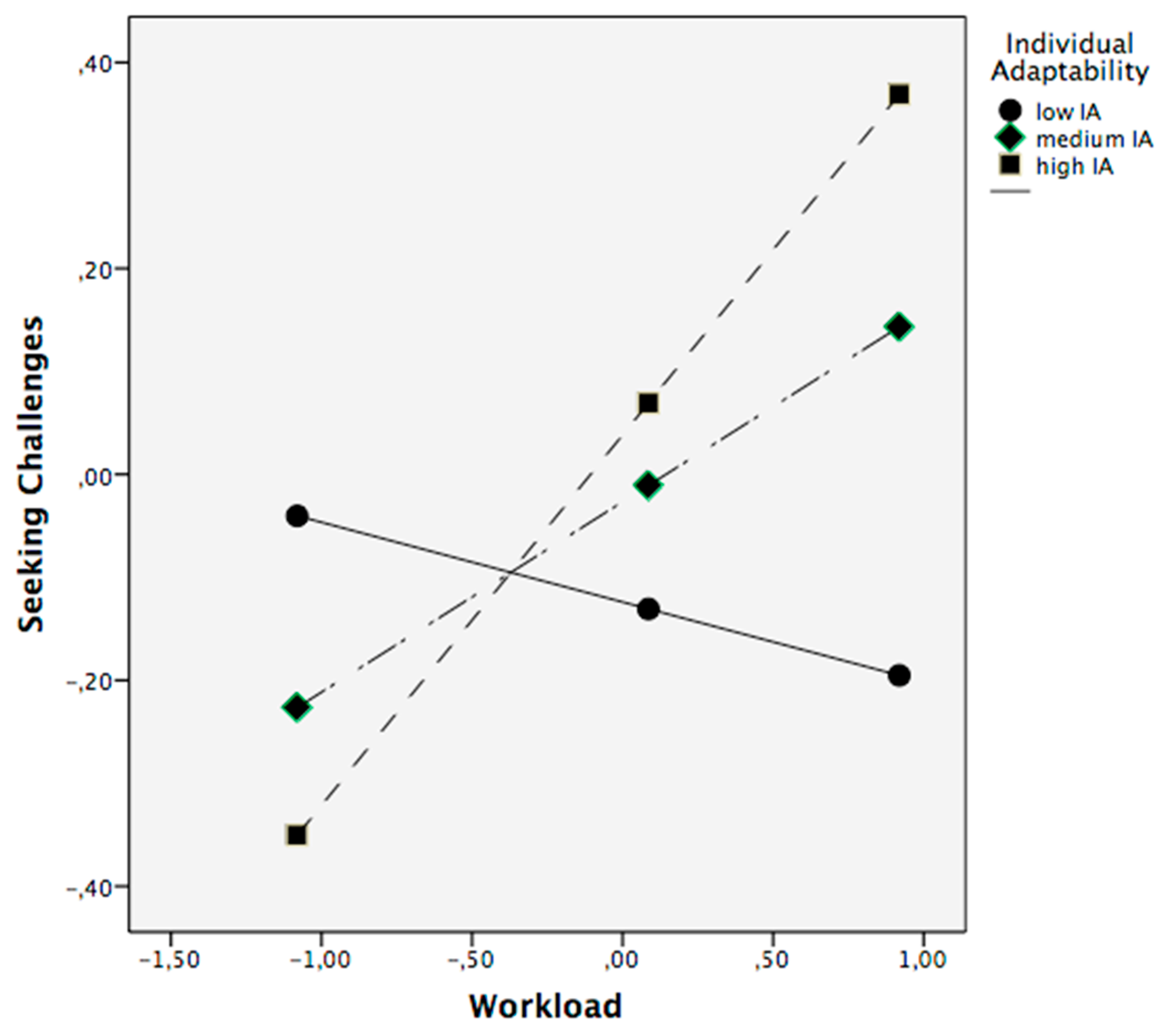

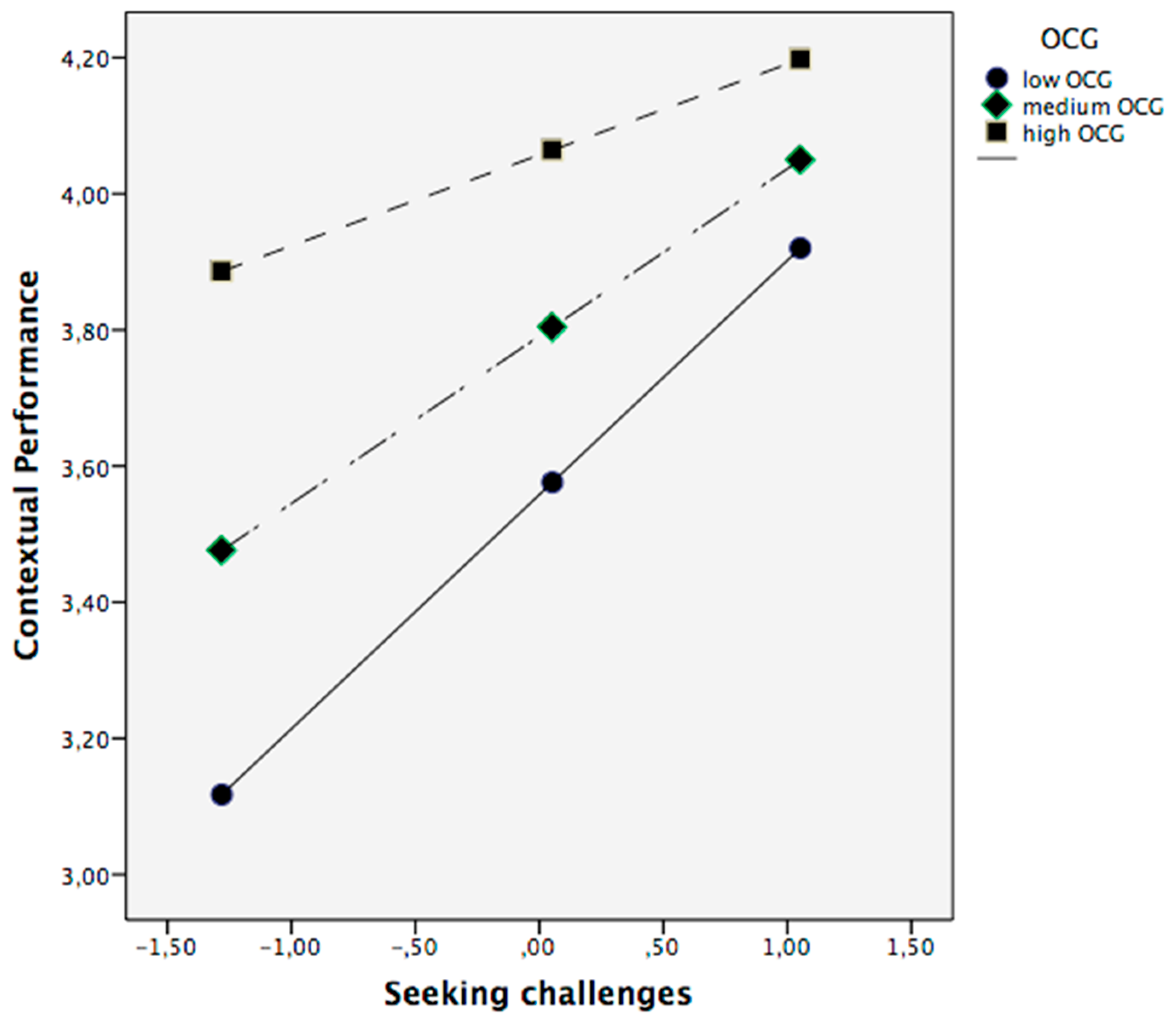

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Theoretical and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ingusci, E. Diversity Climate and Job Crafting: The Role of Age. Open Psychol. J. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, B.; Callea, A.; Urbini, F.; Chirumbolo, A.; Ingusci, E.; De Witte, H. Job insecurity and performance: The mediating role of organizational identification. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1508–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G.S. Creating Healthy Organizations: How Vibrant Workplaces Inspire Employees to Achieve Sustainable Success; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well–being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: A New Frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive healthy organizations: Promoting wellbeing, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Peiró, J. Human capital sustainability leadership to promote sustainable development and healthy organizations: A new scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M.A.; Boswell, W.R.; Roehling, M.V.; Boudreau, J.W. An empirical examination of self–reported work stress among US managers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, C.D.; Ruderman, M.N.; Ohlott, P.J.; Morrow, J.E. Assessing the developmental components of managerial jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenciotti, R.; Borgogni, L.; Callea, A.; Colombo, L.; Cortese, C.G.; Ingusci, E.; Miraglia, M.; Zito, M. The Italian version of the Job Crafting Scale (JCS). BPA Appl. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 277, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; De Vet, H.C.; Van der Beek, A.J. Construct validity of the individual work performance questionnaire. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Bipp, T. Job crafting and performance of Dutch and American health care professionals. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in–role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.M. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Schmitt, N., Borman, W.C., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Gevers, J.M. Job crafting and extra–role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D.; Seifert, C.; Schmutte, B.; Mertini, H.; Holz, M. Emotion work and job stressors and their effects on burnout. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F. A two–wave study on workplace bullying after organizational change: A moderated mediation analysis. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C. Do high workload and job insecurity predict workplace bullying after organizational change? Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2017, 10, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Balducci, C.; Scafuri Kovalchuk, L.; Maiorano, F.; Buono, C. Are Engaged Workaholics Protected against Job-Related Negative Affect and Anxiety before Sleep? A Study of the Moderating Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, A.; McBain, R. Putting the emotion back: Exploring the role of emotion in disengagement. In Individual Sources, Dynamics, and Expressions of Emotion; Zerbe, W.J., Ashkanasy, N.M., Härtel, C.E.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 9, pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A.; Mannix, E.A. The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belschak, F.D.; Den Hartog, D.N. Pro-self, prosocial, and pro-organizational foci of proactive behaviour: Differential antecedents and consequences. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.C.; Arts, R.; Demerouti, E. The crossover of job crafting between coworkers and its relationship with adaptivity. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J.; Ennis, N.; Jackson, A.P. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Bliese, P.D. Individual adaptability (I–ADAPT) theory: Conceptualizing the antecedents, consequences, and measurement of individual differences in adaptability. In Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research (Vol. 6). Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance within Complex Environments; Burke, C.S., Pierce, L.G., Salas, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Successful change leaders: What makes them? What do they do that is different? J. Chang. Manag. 2002, 2, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.Y.; Loi, R. Human resource flexibility, organizational culture and firm performance: An investigation of multinational firms in Hong Kong. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.L.; Edwards, B.D.; Casper, W.C.; Gue, K.R. Employees’ adaptability and perceptions of change-related uncertainty: Implications for perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and performance. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P. Organizational Socialization Learning, Organizational Career Growth, and Work Outcomes. A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Career Dev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Weng, Q.; McElroy, J.C.; Ashkanasy, N.M.; Lievens, F. Organizational career growth and subsequent voice behavior: The role of affective commitment and gender. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 84, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, P.C.; Turner, T.; Ramamoorthy, N.; Pearson, J. Causes and consequences of psychological contracts among knowledge workers in the high technology and financial services industries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 12, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, N.; Flood, P.C.; Slattery, T.; Sardessai, R. Determinants of innovative work behaviour: Development and test of an integrated model. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2005, 14, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Theorell, T.; Karasek, R.A.; Eneroth, P. Job strain variations in relation to plasma testosterone fluctuations in working men-a longitudinal study. J. Intern. Med. 1990, 227, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.X.; Hu, B. The structure of career growth and its impact on employees’ turnover intention. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2009, 14, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnoli, P.; Weng, Q. Factorial validity, cross-cultural equivalence, and latent means examination of the organizational career growth scale in Italy and China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression–Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J.; Almost, J. Testing Karasek’s demands-control model in restructured healthcare settings: Effects of job strain on staff nurses’ quality of work life. J. Nurs. Adm. 2001, 31, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; Jimmieson, N.L. A stress and coping approach to organisational change: Evidence from three field studies. Aust. Psychol. 2003, 38, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.; Hesketh, B. Adaptable behaviours for successful work and career adjustment. Aust. Psychol. 2003, 55, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E.; Manuti, A.; Callea, A. Employability as mediator in the relationship between the meaning of working and job search behaviours during unemployment. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 2016, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Bucci, O. Green positive guidance and green positive life counseling for decent work and decent lives: Some empirical results. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedeian, A.G.; Kemery, E.R.; Pizzolatto, A.B. Career commitment and expected utility of present job as predictors of turnover intentions and turnover behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 1991, 39, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okurame, D.E.; Balogun, S.K. Role of informal mentoring in the career success of first–line bank managers: A Nigerian case study. Career Dev. Int. 2005, 10, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okurame, D. Impact of career growth prospects and formal mentoring on organisational citizenship behaviour. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2012, 33, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Lo Presti, A.; Buono, C. The “dark side” of organizational career growth: Gender differences in work–family conflict among Italian employed parents. (unpublished manuscript).

- Emanuel, F.; Molino, M.; Lo Presti, A.; Spagnoli, P.; Ghislieri, C. A crossover study from a gender perspective: The relationship between job insecurity, job satisfaction and partners’ family life satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; Tims, M. Crafting your career: How career competencies relate to career success via job crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 66, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Contextual performance T2 | 3.77 | 0.69 | (0.82) | |||||||

| 2. Workload T1 | 3.57 | 0.91 | 0.16 | (0.86) | ||||||

| 3. Seeking challenges T1 | 2.95 | 1.09 | 0.38 | 0.13 | (0.83) | |||||

| 4. Individual adaptability T1 | 3.76 | 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.01 | (0.66) | ||||

| 5. Organizational career growth T2 | 2.78 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.27 | −0.01 | (0.95) | |||

| 6. Gender * | 1.63 | 0.48 | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.18 | 0.16 | −0.22 | |||

| 7. Age | 40.56 | 12.59 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.23 | 0.16 | −0.22 | 0.19 | ||

| 8. Tenure | 15.74 | 12.17 | 0.12 | 0.07 | −0.21 | 0.14 | −0.13 | 0.21 | 0.89 |

| Models | B | LLCI | ULCI | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Model 1: Mediation of seeking challenges T1 in the relationship between workload T1 and contextual performance T2 Outcome variable: Seeking challenges T1 | 0.10 * | |||

| Workload T1 | 0.18 * | −0.70 | −0.02 | |

| Covariate: Gender | −0.36 | −0.70 | −0.02 | |

| Covariate: Age | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.01 | |

| Covariate: Tenure | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 | |

| b. Model 1: Mediation of seeking challenges T1 in the relationship between workload T1 and contextual performance T2 Outcome variable: Contextual performance T2 | 0.20 ** | |||

| Seeking challenges T1 | 0.25 * | 0.17 | 0.35 | |

| Workload T1 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.17 | |

| Covariate: Gender | −0.05 | −0.26 | 0.14 | |

| Covariate: Age | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Covariate: Tenure | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.13 | |

| c. Model 2: Mediation model including interaction terms Outcome variable: Seeking challenges T1 | 0.13 ** | |||

| Workload T1 | 0.15 | −0.02 | 0.33 | |

| Adaptability T1 | 0.16 | −0.14 | 0.46 | |

| Workload T1 × Adaptability T1 | 0.44 ** | 0.11 | 0.76 | |

| Covariate: Gender | −0.37 | −0.71 | −0.04 | |

| Covariate: Age | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | |

| Covariate: Tenure | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | |

| d. Model 2: Mediation model including interaction terms Outcome variable: Contextual performance T2 | 0.32 ** | |||

| Workload T1 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.17 | |

| Seeking challenges T1 | 0.24 ** | 0.15 | 0.33 | |

| Organizational career growth T2 | 0.25 ** | 0.15 | 0.35 | |

| Seeking challengesT1 × Organizational career growth T2 | −0.10 * | −0.19 | −0.20 | |

| Covariate: Gender | 0.02 | −0.16 | 0.22 | |

| Covariate: Age | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Covariate: Tenure | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Index of moderated mediation | Index | |||

| −0.05 | −0.11 | −0.01 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ingusci, E.; Spagnoli, P.; Zito, M.; Colombo, L.; Cortese, C.G. Seeking Challenges, Individual Adaptability and Career Growth in the Relationship between Workload and Contextual Performance: A Two-Wave Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020422

Ingusci E, Spagnoli P, Zito M, Colombo L, Cortese CG. Seeking Challenges, Individual Adaptability and Career Growth in the Relationship between Workload and Contextual Performance: A Two-Wave Study. Sustainability. 2019; 11(2):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020422

Chicago/Turabian StyleIngusci, Emanuela, Paola Spagnoli, Margherita Zito, Lara Colombo, and Claudio G. Cortese. 2019. "Seeking Challenges, Individual Adaptability and Career Growth in the Relationship between Workload and Contextual Performance: A Two-Wave Study" Sustainability 11, no. 2: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020422

APA StyleIngusci, E., Spagnoli, P., Zito, M., Colombo, L., & Cortese, C. G. (2019). Seeking Challenges, Individual Adaptability and Career Growth in the Relationship between Workload and Contextual Performance: A Two-Wave Study. Sustainability, 11(2), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020422