Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Study

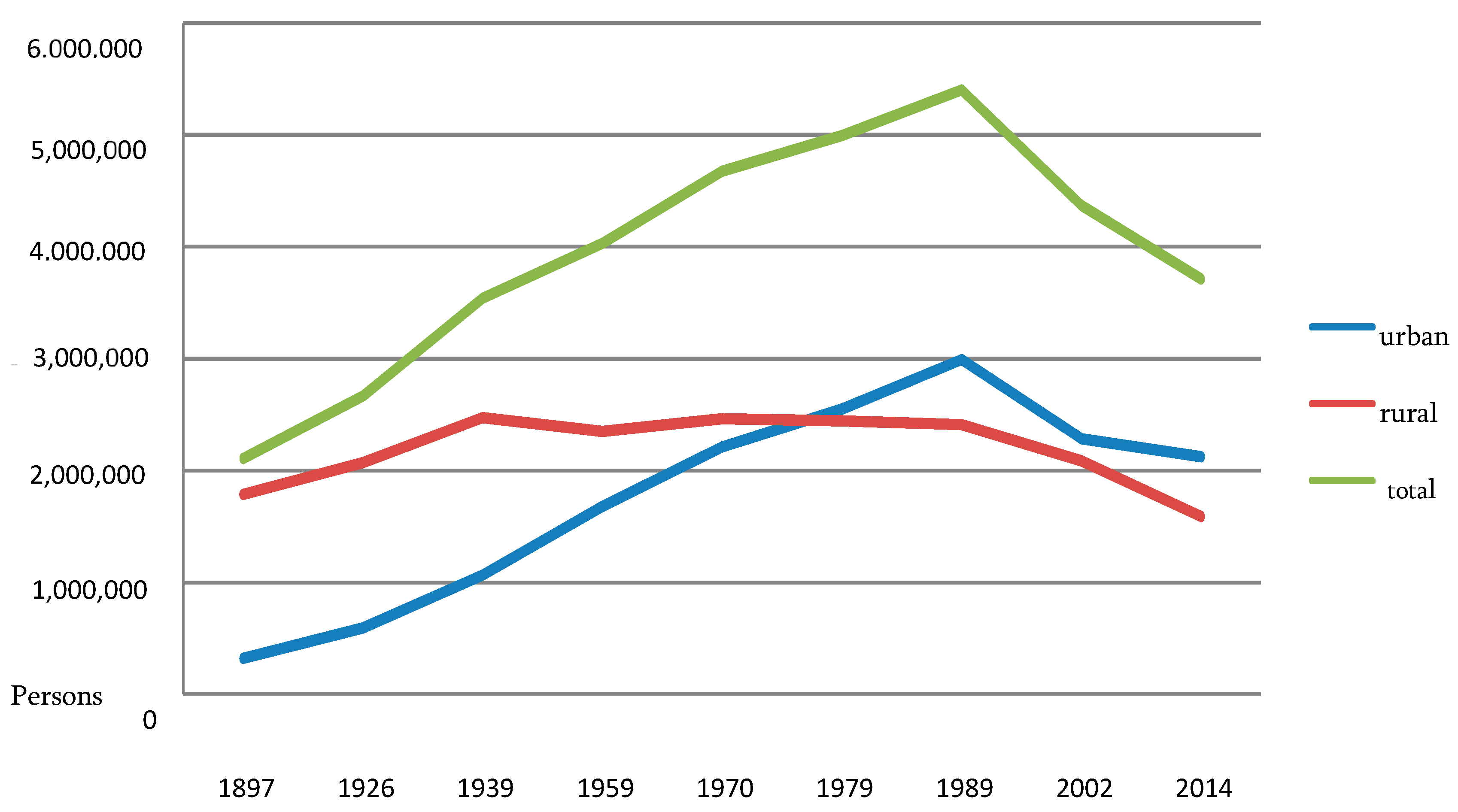

1.2. Key Facts about Georgia

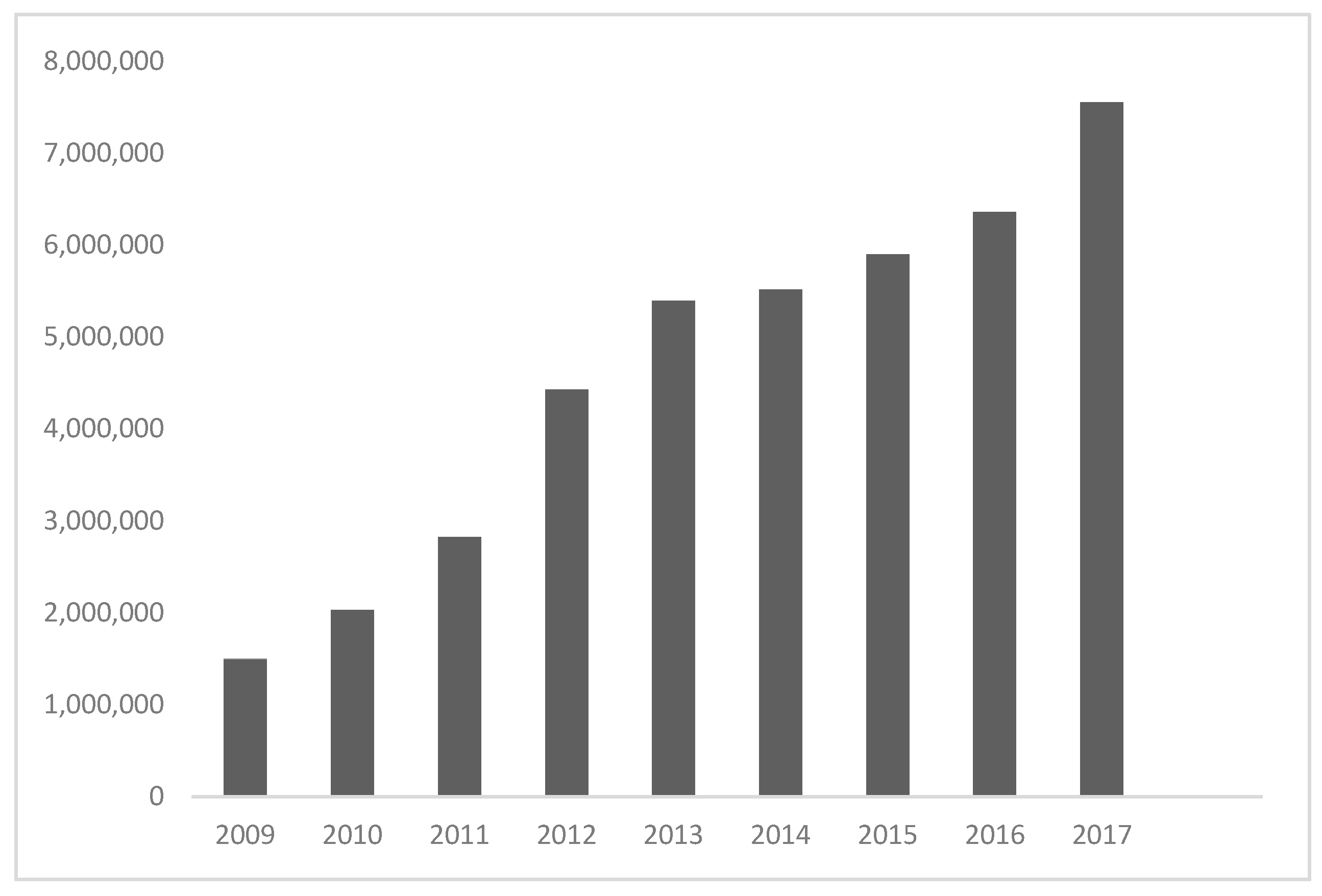

1.3. Tourism in the Post-Soviet Era in the Context of Transition

2. Rural Tourism in Europe

2.1. Concepts and Definitions

2.2. The Role of Rural Tourism in Sustainable Regional Development

2.3. Institutional Development of Rural Tourism: Networks and Associations in Europe

3. Study Design

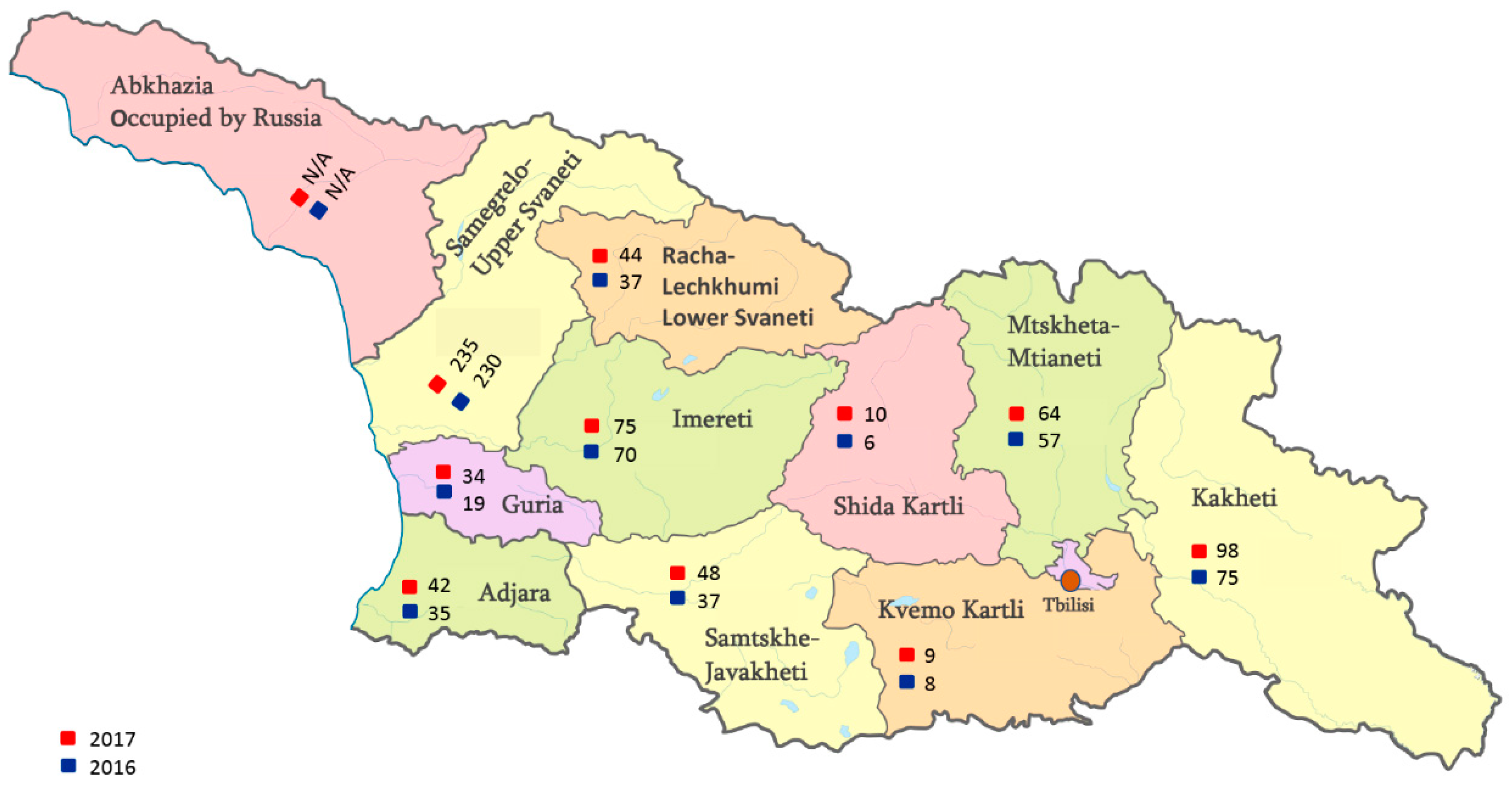

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Research Objectives

- Identify the current status of Rural Tourism in Georgia: key terms, definitions, and institutional development;

- Explore the perception of the role of Rural Tourism by different stakeholders in the context of sustainable development;

- Discuss the revealed problems and constraints; and

- Develop recommendations and relevant actions to ensure a sustainable future for Rural Tourism in Georgia.

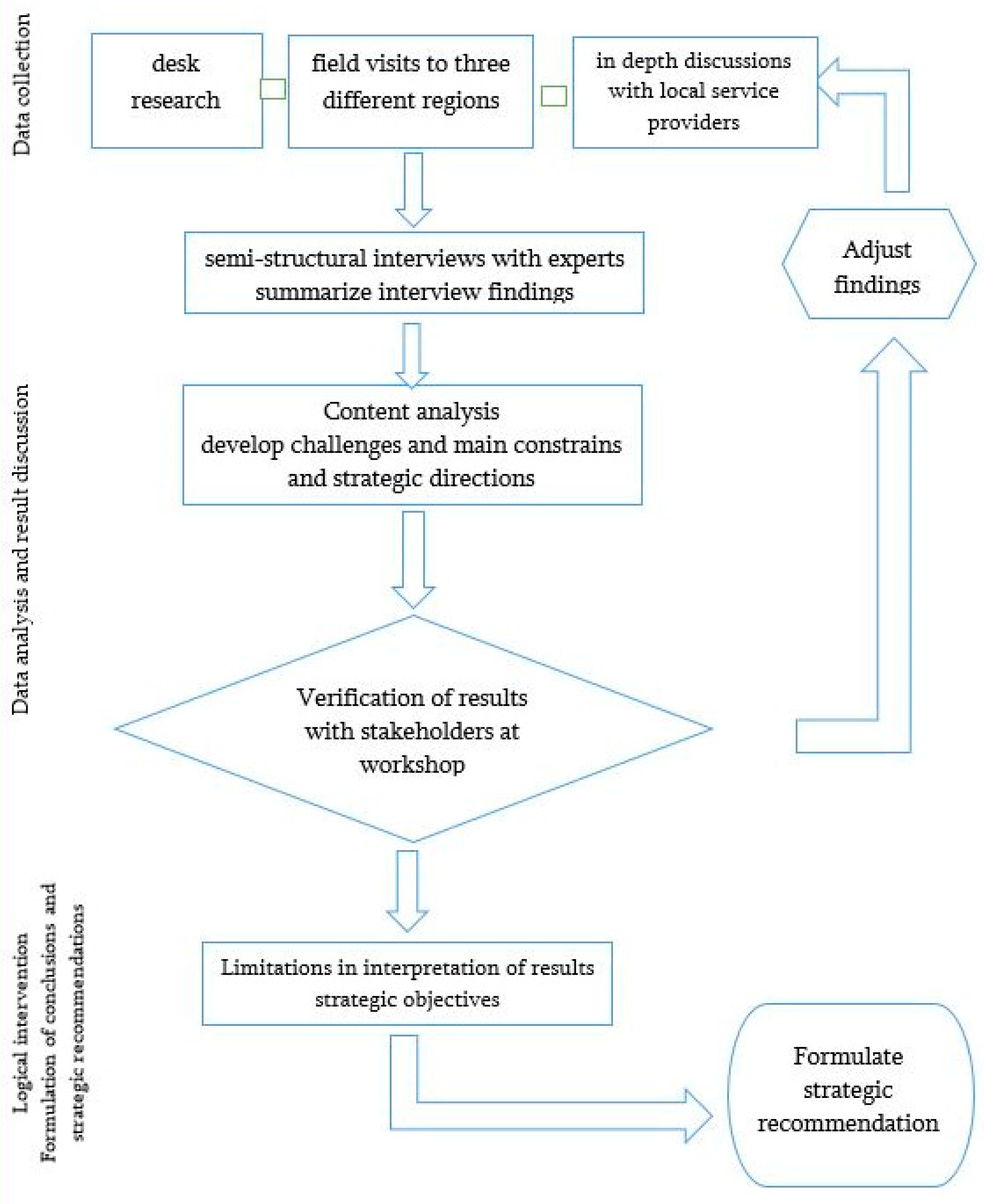

3.3. Research Methods

4. Findings

4.1. Rural Tourism in Georgia

4.1.1. Evolution and Development of Understanding

4.1.2. National Policy Framework for Rural Tourism

4.1.3. International Projects on Rural and Agritourism

4.2. Actors’ Views on Rural Tourism and Regional Development

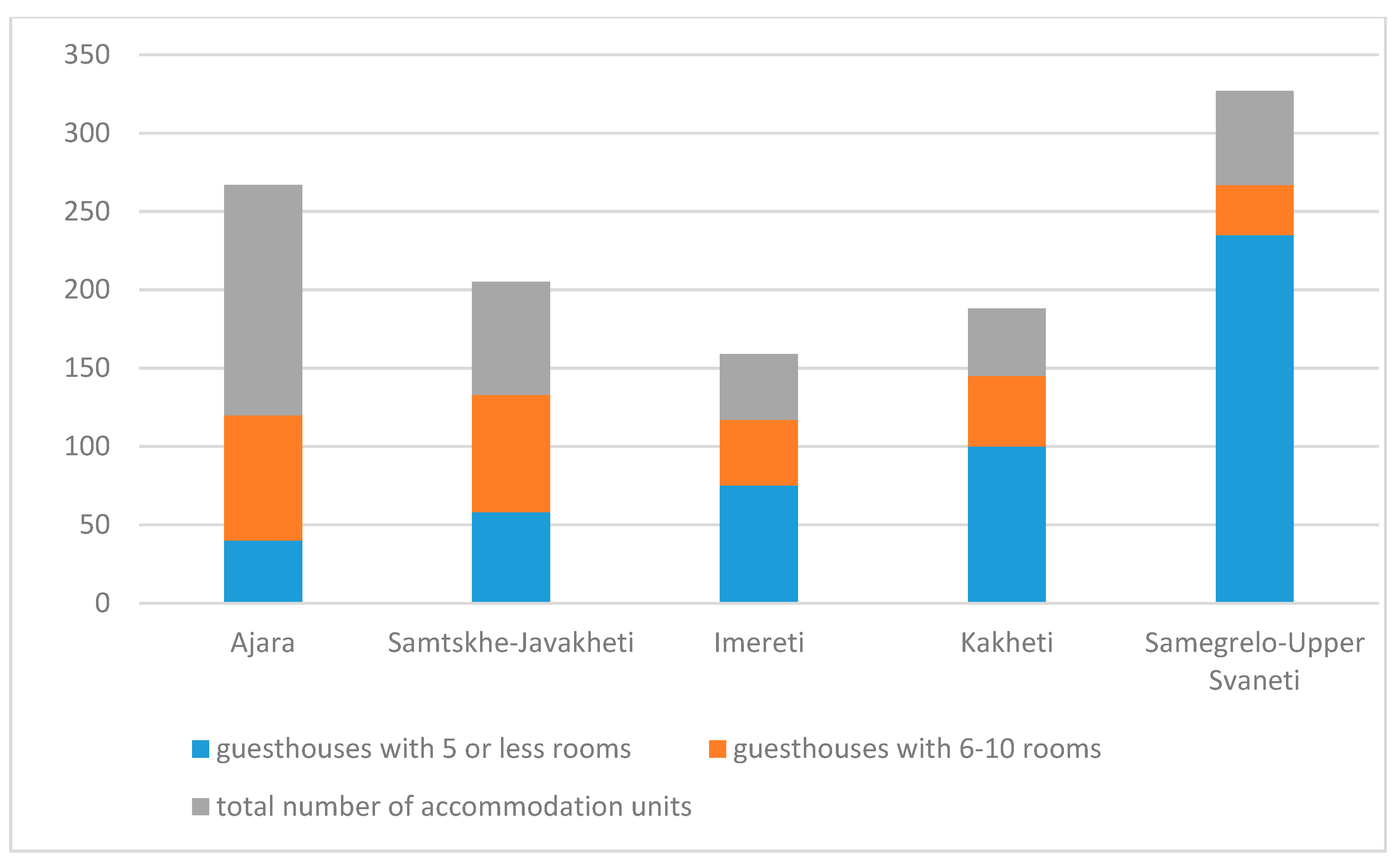

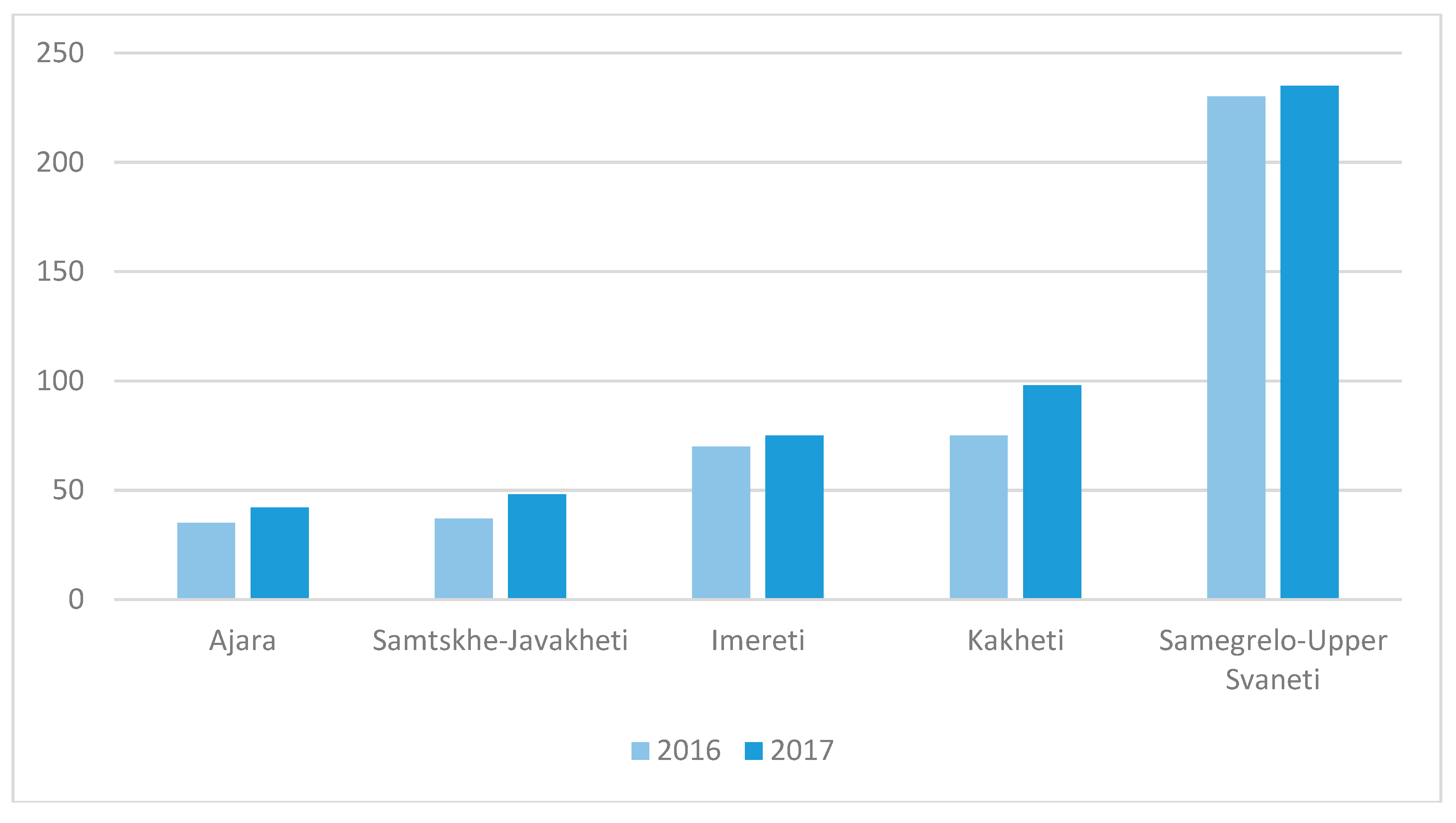

4.3. Rural Tourism Entrepreneurs and Tourism Products

5. Discussion: Problems and Constraints

5.1. Missing Central Support Structure for Rural Tourism

5.2. Limited Common Understanding of Rural Tourism

5.3. Lack of Innovative Rural Tourism Products

5.4. Lack of Awareness and Capacity on Local and National Levels

5.5. Low Visibility of Georgian Rural Tourism at the National and International Level

6. Possible Limitations of the Study

7. Proposals for Institutionalization and Further Management Actions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lane, B. Rural tourism: An overview: The SAGE Handbook of Tourism Studies; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Committee on Tourism Secretariat. Tourism Strategies and Rural Development; OECD: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches–Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizbarashvili, N.; Meessen, H.; Khoetsyan, A.; Meladze, G.; Kohler, T. Sustainable Development of Mountain Regions and Resource Management: Textbook for Students of Higher Educations; TSU: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2018; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville, P.; Lee, E.; Shavgulidze, R.; Kvitaishvili, I. Analytical Foundations Assessment–Agriculture (Rural Productivity); USAID/Georgia: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, D.J.; Wegren, S.K. (Eds.) Rural Reform in Post-Soviet Russia; Woodrow Wilson Center Press with Johns Hopkins University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liberal Academy Tbilisi. The Economic Transformation of Georgia in its 20 Years of Independence: Summary of the Discussion Paper; EastWest Management Institute (EWMI): Tbilisi, Georgia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics office of Georgia (Geostat). General Population Census; Geostat: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gugushvili, T.; Salukvadze, G.; Salukvadze, J. Fragmented development: Tourism-driven economic changes in Kazbegi, Georgia. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paresishvili, O.; Kvaratskhelia, L.; Mirzaeva, V. Rural tourism as a promising trend of small business in Georgia: Topicality, capabilities, peculiarities. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2017, 15, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkladze, R. Modern trends and prospects to develop the agrarian sector of Georgia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badurashvili, I.; Nadareishvili, M. Social Impact of Emigration and Rural-Urban Migration in Central and Eastern Europe, Final Country Report; 2012. Available online: ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=8862&langId=fr (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Ministry of Agriculture of Georgia. Rural Development Strategy of Georgia 2017-2020: Prepared within the framework of ENPARD; MEPA: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- State Commission on Migration Issues. 2015 Migration Profile of Georgia; International Centre for Migration Policy Development: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chumburidze, M.; Ghvinadze, N.; Gvazava, S.; Hosne, R.; Wagner, W.; Zurabishvili, T. The State of Migration in Georgia: Report Developed in the framework of the EU-Funded Enhancing Georgia’s Migration Management (ENIGMMA) Project; International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD): Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Voll, F.; Mosedale, J. Political-economic transition in Georgia and its implications for tourism in Svaneti. TIMS. Acta 2015, 9, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oedl-Wieser, T.; Dax, T.; Fischer, M. A new approach for participative rural development in Georgia–refl ecting transfer of knowledge and enhancing innovation in a non-European Union context. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2017, 119, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelashvili, I. Принципы и метoды oценки рекреациoнных ресурсoв для инoстраннoгo туризма СССР (на примереГрузинскoй ССР)., Автoрефераты и диссертации o прирoде и Земле в научнoй библиoтеке Earthpapers. Диссертации o Земле; 1984. Available online: http://earthpapers.net/#ixzz5OzpeGVyr (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Cappucci, M.; Pavliashvili, N.; Zarrilli, L. New trends in mountain and heritage tourism: The case of upper svaneti in the context of georgian tourist sector. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2015, 15, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pertaia, G. Dynamic Investment Growth in Georgia. In THE GEORGIAN -Travel and Trade Guide; TTG Georgia Ltd.: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2013; Available online: www.thegeorgianonline.com (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Papava, N.; Iremashvili, G. Georgia’s Tourism Sector: Shifting into High Gear; Industry overview; Galt & Taggart Ltd.: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- TTG Georgia. Invest in Georgia 2017. Available online: www.thegeorgiaonline.com (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Georgian National Tourism Administration. Georgian Tourism in Figures. Available online: https://gnta.ge/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ENG-2016.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2017; World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC): London, UK, 2017.

- Gyr, U. The History of Tourism: Structures on the Path to Modernity; European History Online (EHO), 2010. Available online: http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/the-history-of-tourism (accessed on 13 January 2019).

- Irshad, H. Rural tourism–An Overview; Government of Alberta, Agricultre and Rural Development: Alberta, Canada, 2010.

- Lane, B. (Ed.) Second generation rural tourism: Research priorities and issues. In Proceedings of the Atas do VIII CITURDES: Turismo Rural em Tempos de Novas Ruralidades, Chaves, Portugal, 25–27 June 2012; pp. 1021–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, A.; Pizam, A. Rural tourism in Israel. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. (Ed.) The Evolution of Tourism and Development Theory. In Tourism and development: Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2002; pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.; Weingarten, P. Farm Tourism: Myth or Reality. In The Role of Agriculture in Central and Eastern European Rural Development: Engine of Change or Social Buffer? Institut für Agrarentwicklung in Mittel- und Osteuropa (IAMO): Halle, Germany, 2004; pp. 286–304. [Google Scholar]

- Clemenson, H.A.; Lane, B. Niche markets, niche marketing and rural employment. In Rural Employment: An International Perspective; Bollman, R.D., Bryden, J.M., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1997; pp. 410–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kizos, T.; Iosifides, T. The contradictions of agrotourism development in Greece: evidence from three case studies. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2007, 12, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idziak, W.; Majewski, J.; Zmyślony, P. Community participation in sustainable rural tourism experience creation: a long-term appraisal and lessons from a thematic villages project in Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1341–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A community Approach (RLE Tourism); Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, G. Relationships, networks and the learning regions: case evidence from the Peak District National Park. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and social sustainable synergies to promote innovations in rural tourism and local development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstad, H.K. Development of rural-tourism experiences through networking: An example from Gudbrandsdalen, Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian J. Geogr. 2014, 68, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayat, K. (Ed.) Community-based rural tourism: A proposed sustainability framework; EDP Sciences: Les Uls, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Division of Technology. In Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; UNEP and WTO Publication: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf, J. The Holiday Markers; Heinemann: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, A.; Kline, C. Rural tourism and the craft beer experience: Factors influencing brand loyalty in rural North Carolina, USA. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1198–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajder, M.; Przezbórska, L.; Scrimgeour, F. Agritourism; CABI: Walingford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, M.D.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T.; Vuković, D.B.; Radovanović, M.; Jovanović, J.M.; Vuković, N. Tourism as an Approach to Sustainable Rural Development in Post-Socialist Countries: A Comparative Study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability 2017, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Quality Management in Urban Tourism; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. Tourism: A community approach. Methuen: New York and London. Tour. Rev. 1985, 6, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bojnec, S. Rural tourism, rural economy diversification, and sustainable development. Academica Turistica, Year 2010, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Asker, S.A.; Boronyak, L.J.; Carrard, N.R.; Paddon, M. Effective Community Based Tourism: A Best Practice Manual; Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavita, E.; Saarinen, J. Tourism and rural community development in Namibia: Policy issues review. Fennia-Int. J. Geogr. 2016, 194, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiran, A.; Jităreanu, A.F.; Gîndu, E.; Ciornei, L. Development of rural tourism and agrotourism in some european countries. Lucrări Științifice Management Agricol 2016, 18, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Embacher, H. Farm Holidays in Austria—Strategy and Contributions towards Sustainability; Austrian Farm Holidays Association: Salzburg, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Verbole, A. Rural tourism and sustainable development: a case study on Slovenia; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, H.; Santilli, R. Community-based tourism: A success. ICRT Occasional paper; 2009. Available online: http://www.haroldgoodwin.info/uploads/CBTaSuccessPubpdf.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Muckosy, P.; Mitchell, J. A Misguided Quest: Community-Based Tourism in Latin America; ODI: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klepers, A. Problems of Creating Micro-Clusters in Small-Scale Tourism Destinations. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki 2010, 14, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, R.; Lynch, P. Small tourism business networks and destination development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 20, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkana. Rural Tourism Network. Available online: www.ruraltourism.ge (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Khartishvili, L. Rural Tourism; Elkana: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, S.; Hunter, C.; Blackstock, K. A typology for defining agritourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirse, J.; Khartishvili, L. Strategy for Tourism Development in Protected Areas of Georgia; 2016. Available online: http://tjs-caucasus.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Ecotourism-PA-Georgia-Strategy_Final.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Government of Georgia. Law of Georgia on the Development of High Mountainous Regions; Parliament of Georgia: Kutaisi, Georgia, 2015.

- Economic Policy Department of the Ministry for Economy and Sustainable Development. SME Development Strategy of Georgia 2016-2020; Economic Policy Department of the Ministry for Economy and Sustainable Development: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EU-Georgia. Association Agreement between the EU and Georgia: AA. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Country Programming Framework for Georgia 2016-2020; FAO: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hadorn, G.H.; Bradley, D.; Pohl, C.; Rist, S.; Wiesmann, U. Implications of transdisciplinarity for sustainability research. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhobaia, M. Tourism policy challenges in Post-Soviet Georgia. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2015, 9, 986–989. [Google Scholar]

- Georgian National Tourism Administration. The Law of Georgia on Tourism and Resorts; Parliament of Georgia: Tbilisi, Georgia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lekashvili, E.; Dodashvili, V. Legal Regulation of Tourism Business in Georgia. Copernic. J. Financ. Account. 2017, 6, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhar, A.; Siegrist, D. 10 Synergies Between Tourism, Outdoor Recreation and Landscape Stewardship. In The Science and Practice of Landscape Stewardship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 184–199. [Google Scholar]

| Name of Organizations | Type |

|---|---|

| Government NGO Government NGO Private enterprise NGO NGO NGO NGO NGO NGO NGO NGO Government NGO Government NGO NGO Government NGO Government NGO International institution |

| Field of Intervention | Proposed Actions |

|---|---|

| Management and governance | to promote communication and cooperation (at both the national and regional level) between rural-tourism-related national associations, the National Tourism Administration, related NGOs, and other institutions through (proposed) institutions/agencies; take into account the interests of stakeholders in decision-making processes; initiate joint projects |

| to develop a policy and initiate the creation of legal regulations for rural tourism in line with the new policy directions (E.U.–Georgia Association Agreement) | |

| to organize and develop a network of destination management organizations in the country as appropriate | |

| to internationalize destination management organization activities by initiating exchange and joint projects with European partners, such as twinning projects with other regions in Europe (e.g., South Tyrol in Italy or Tyrol in Austria), for developing marketing plans for destinations | |

| Capacity building and raising awareness | to organize systematic training and provide useful and updated materials for communicating innovations in tourism and hospitality, business planning and administration, destination management, and marketing |

| to organize forums, conferences, and other events on rural tourism at destinations with the participation of various stakeholders, including practitioners and researchers | |

| Product development and diversification | to facilitate the development of innovative, community-based tourism products and multiple experiences |

| Marketing, branding | to promote Rural Tourism through international and national fairs and e-marketing to raise awareness about regional identity and facilitate cooperation between small and medium enterprises (SMEs) through the establishment of common quality criteria and destination brands |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khartishvili, L.; Muhar, A.; Dax, T.; Khelashvili, I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020410

Khartishvili L, Muhar A, Dax T, Khelashvili I. Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability. 2019; 11(2):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020410

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhartishvili, Lela, Andreas Muhar, Thomas Dax, and Ioseb Khelashvili. 2019. "Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability" Sustainability 11, no. 2: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020410

APA StyleKhartishvili, L., Muhar, A., Dax, T., & Khelashvili, I. (2019). Rural Tourism in Georgia in Transition: Challenges for Regional Sustainability. Sustainability, 11(2), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020410