Boundary Conditions of the Curvilinear Relationships between Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and New Product Performance: Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility: A Double-Edged Sword

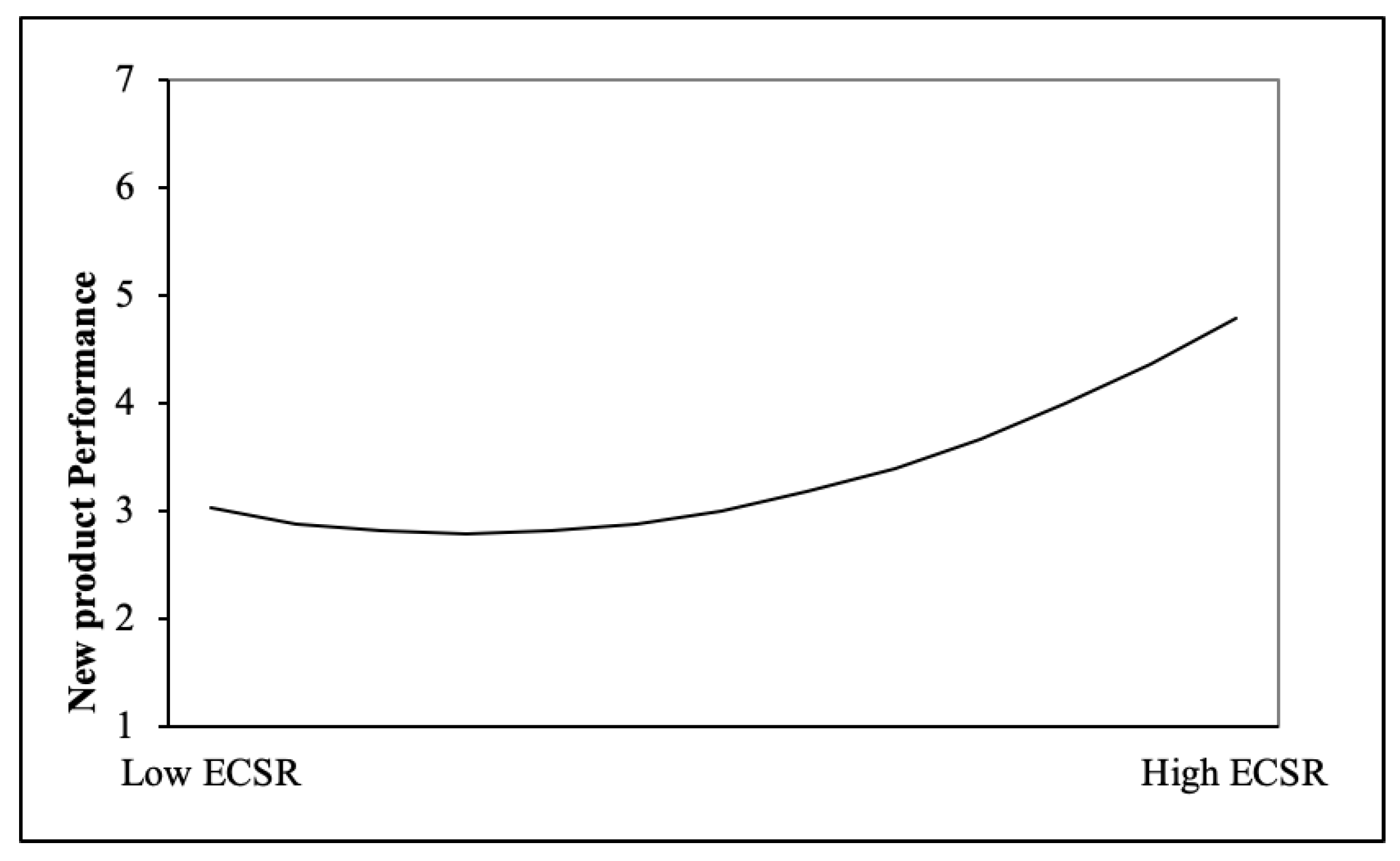

2.2. ECSR and New Product Performance

2.3. Influential Effects of Institutional Development Level and Ownership Types

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Independent Variable

3.2.2. Moderator Variables

3.2.3. Dependent Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Construct Validity and Reliability

4.2. Hypothesis Testing and Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item (Composite Reliability) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements according to your company? | ||

| Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility(0.92) | 0.90 | |

| (Adopted from Orsato 2006) | ||

| In the past three years, your company has Protected the environment | 0.86 | |

| Maintained an ethical working environment | 0.87 | |

| Utilized resources wisely and responsibly | 0.91 | |

| Economized the usage of raw materials | 0.85 | |

| Recycled our products | 0.72 | |

| New Product Development Performance (0.91) | 0.87 | |

| (Adopted from Kim and Atuahene-Gima, 2010) In the past three years, whether the new product development performance of your company is better than your major competitors’ in | ||

| Profit | 0.84 | |

| Sales | 0.90 | |

| Customer satisfaction | 0.78 | |

| Market shares | 0.87 | |

References

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Post, C. Measurement issues in environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR): Toward a transparent, reliable, and construct valid instrument. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. Study on the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. How does environmental corporate social responsibility matter in a dysfunctional institutional environment? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis and redirection of research on the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Ann. Arbor 2007, 1001, 48109-1234. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, C.; Zhou, K.Z.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, S. How green management influences product innovation in China: The role of institutional benefits. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Wang, L.F.; Lee, S.H. Strategic environmental corporate social responsibility in a differentiated duopoly market. Econ. Lett. 2015, 129, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Lee, S.H.; Matsumura, T. Environmental corporate social responsibility: A note on the first-mover advantage under price competition. Econ. Bull. 2017, 37, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Su, W.; Peng, M.W.; Tan, W.; Cheung, Y.L. The signaling effect of corporate social responsibility in emerging economies. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y. Regulatory uncertainty and corporate responses to environmental protection in China. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Jia, C.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, W. Environmental management under subnational institutional constraints. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Corporate social responsibility and the environment: A theoretical perspective. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2008, 2, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas-Cruz, Y.; Gil-Soto, E.; Oreja-Rodríguez, J.R. Environmental management in SMEs: Organizational and sectoral determinants in the context of an Outermost European Region. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Competing for government procurement contracts: The role of corporate social responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1299–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive Environmental Strategies: When Does It Pay to be Green? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, S.; Kalaignanam, K.; Eilert, M. Product and environmental social performance: Varying effect on firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Liu, H.; Fan, P.; Wei, Z. Does CSR practice pay off in East Asian firms? A meta-analytic investigation. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder’s value. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Cohen, M.A.; Elgie, S.; Lanoie, P. The Porter Hypothesis at 20: Can Environmental Regulation Enhance Innovation and Competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Does It Pay to Be Different? An Analysis of the Relationship between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1325–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zuzul, T.; Jones, G.; Khanna, T. Overcoming institutional voids: A reputation-based view of long-run survival. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2147–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Luo, J. An economic case for CSR: The comparative efficiency of for-profit firms in meeting consumer demand for social goods. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1650–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C.; Jbusres, J. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: The moderating role of reputation and institutional investors. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Vieira, E.T. Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights from oil companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, Y.M.; Yang, S.L. Does engagement in corporate social responsibility provide strategic insurance-like effects? Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Luo, J. Corporate social responsibility as an employee governance tool: Evidence from a quasi-experiment. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremeth, A.R.; Shaver, J.M. Strategic rationale for responding to extra-jurisdictional regulation: Evidence from firm adoption of renewable power in the US. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peloza, J. The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1518–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, D.; Wright, G.; Peattie, K. Green and competitive: Influences on environmental new product development performance. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, Y. Industrial Ownership and Environmental Performance: Evidence from China. Environ. Resour. Econ 2007, 36, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, D.P. A Positive Theory of Moral Management, Social Pressure, and Corporate Social Performance. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D.P.; Diermeier, D. Strategic Activism and Nonmarket Strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2007, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, C.E.; Lu, J.; Tao, Z. Property rights protection and access to bank loans: Evidence from private enterprises in China. Econ. Transit. 2006, 14, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N. Are collective political actions and private political actions substitutes or complements? Empirical evidence from China’s private sector. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, M.M. China’s New Business Elite: The Political Consequences of Economic Reform; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. J. Public Econ. 2006, 89, 1719–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.; Holzinger, I. The effectiveness of strategic political management: A dynamic capabilities framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 496–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonenshein, S.; DeCelles, K.A.; Dutton, J.E. It’s not easy being green: The role of self-evaluations in explaining support of environmental issues. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, T. Gaining access by doing good: The effect of sociopolitical reputation on firm participation in public policy making. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 1989–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, I.J.; Bhatt, M.; Bartunek, J.M. Organizational knowledge creation in the Chinese context. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2009, 5, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, C.V.; Peng, M.W.; Bruton, G.D. Slack and the performance of state-owned enterprises. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: Evidence from China. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Eden, L.; Lau, C.M.; Wright, M. Strategy in emerging economies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Qian, C. Principal-principal conflicts under weak institutions: A study of corporate takeovers in China. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Provinces 2011 Report; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, K.F. Picturing firms’ institutional capital-based radical innovation under China’s institutional voids. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bruggen, G.H.; Lilien, G.L.; Kacker, M. Informants in organizational marketing research: Why use multiple informants and how to aggregate responses. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Sun, S.L.; Peng, M.W. Sub-national institutional contingencies, network positions, and IJV partner selection. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1221–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yue, H.; Zhao, L. Ownership, institutions, and capital structure: Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2009, 37, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.; Makino, S.; Isobe, T. Does subnational region matter? Foreign affiliate performance in the United States and China. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Using exploratory and exploitative market learning for new product development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2010, 27, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Zeitz, G.J. Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.; West, S. The Effects of Predictor Scaling on Coefficients of Regression Equations; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Sun, S.L.; Pinkham, B.; Chen, H. The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Lau, C.M. Asian management research: Status today and future outlook. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 636–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Benefits | Behavioral | Infrastructural |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Organizational commitment and loyalty by employees [35] | Operational efficiency [13,22] Intangible resources [12] Legal and cleanup costs reduction [1] Improvements in waste reductions and process enhancements [37] A focus/differentiation-based strategy Reduce risk [36] |

| External | Green images reputation [11,12] Legitimacy [4,6] Long-term competitive advantages [23,24,38] Stakeholder relationship [11,30,39] Customer satisfaction [33] Trust and goodwill [28,29,31,40] | Reshape marketing rules in the market [13] |

| Costs | Behavioral | Infrastructural |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Internal resistance [41] | Decrease profits Cost of integrating environmental management philosophy with internal structure High fixed and variable costs [26] |

| External | Increasing market risk | Violate the contractual relationship with shareholders [1,24] |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ownership | -- | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Firm age | 0.25 ** | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Firm size | 0.18 ** | 0.50 ** | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Machinery manufacturing. | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.05 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Aerospace | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.05 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 6. Chemical | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.13 * | −0.04 | -- | ||||||||||||

| 7. Pharmaceutical | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.05 | -- | |||||||||||

| 8. IT | −0.15 ** | 0.10 | 0.16 ** | −0.12 * | −0.04 | −0.09 | −0.05 | -- | ||||||||||

| 9. Food | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.06 | -- | |||||||||

| 10. Other industries | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.14 * | −0.04 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.07 | -- | ||||||||

| 11. Market index | −0.26 ** | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.31 ** | −0.06 | 0.04 | -- | |||||||

| 12. ECSR | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.13 * | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.84 | ||||||

| 13. New product development performance | −0.13 * | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.17 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.85 | |||||

| 14. Market share | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.22 ** | 0.27 ** | -- | ||||

| 15. R&D input | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −0.09 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.21 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.58 ** | -- | |||

| 16. Technology advancing | −0.04 | 0.14 * | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.11 * | −0.02 | 0.20 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.05 | 0.08 | -- | ||

| 17. Competition intensity | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.16 ** | 0.08 | 0.12 * | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.46 ** | -- | |

| 18. Manager as NPC member | 0.23 ** | 0.09 | 0.20 ** | −0.00 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.16 ** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.16 ** | 0.18 ** | -- |

| Mean | 0.39 | 23 | 6.42 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 7.25 | 5.31 | 4.98 | 5.48 | 4.81 | 4.61 | 4.81 | 4.18 |

| SD | 0.49 | 19.66 | 1.97 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 2.11 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.48 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | VIF | B | VIF | B | VIF | |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Firm age | −0.08 | 1.40 | −0.04 | 1.43 | −0.01 | 1.57 |

| Firm size | 0.12 + | 1.49 | 0.09 | 1.52 | 0.09 | 1.58 |

| Machinery manufacturing | −0.03 | 1.13 | −0.03 | 1.14 | −0.05 | 1.16 |

| Aerospace | 0.08 | 1.03 | 0.07 | 1.03 | 0.09 | 1.07 |

| Chemical | 0.01 | 1.08 | 0.00 | 1.08 | 0.01 | 1.11 |

| Pharmaceutical | 0.07 | 1.05 | 0.06 | 1.05 | 0.06 | 1.07 |

| IT | 0.03 | 1.13 | −0.01 | 1.16 | −0.05 | 1.30 |

| Food | −0.05 | 1.06 | −0.08 | 1.08 | −0.09 | 1.11 |

| Other industries | 0.12 * | 1.09 | 0.08 | 1.12 | 0.09 | 1.14 |

| Market share | 0.14 * | 1.72 | 0.11 + | 1.73 | 0.12 + | 1.76 |

| R&D input | 0.23 ** | 1.75 | 0.18 ** | 1.78 | 0.17 | 1.84 |

| Technology advancing | 0.18 ** | 1.34 | 0.11 + | 1.40 | 0.11 | 1.48 |

| Competition intensity | 0.07 | 1.36 | 0.09 | 1.39 | 0.10 | 1.42 |

| Manager as NPC member | −0.07 | 1.13 | −0.10 + | 1.14 | −0.10 | 1.22 |

| Direct Effects | ||||||

| Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility (ECSR) | 0.30 *** | 1.23 | 0.29 *** | 1.31 | ||

| ECSR × ECSR | 0.14 ** | 1.08 | 0.11 * | 1.13 | ||

| Market Index (MI) | 0.13 + | 2.09 | ||||

| Ownership | −0.01 | 1.94 | ||||

| Interactions | ||||||

| ECSR × MI | 0.04 | 1.24 | ||||

| ECSR × Ownership | 0.03 | 1.22 | ||||

| ECSR × ECSR × MI | −0.14 * | 1.93 | ||||

| ECSR × ECSR × Ownership | −0.14 + | 1.91 | ||||

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.32 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.26 | |||

| ΔR2 | 0.08 | 0.03 | ||||

| F-Value | 5.24 *** | 7.17 *** | 5.75 *** | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, S.; Huang, K.-F. Boundary Conditions of the Curvilinear Relationships between Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and New Product Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184968

Yang Z, Zhang Y, Gao Y, Gao S, Huang K-F. Boundary Conditions of the Curvilinear Relationships between Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and New Product Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184968

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Zhuoer, Yahui Zhang, Yu Gao, Shanxing Gao, and Kuo-Feng Huang. 2019. "Boundary Conditions of the Curvilinear Relationships between Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and New Product Performance: Evidence from China" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184968

APA StyleYang, Z., Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Gao, S., & Huang, K.-F. (2019). Boundary Conditions of the Curvilinear Relationships between Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and New Product Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 11(18), 4968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184968