Geochemical Characteristics of Rare Earth Elements in Soils from Puding Karst Critical Zone Observatory, Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

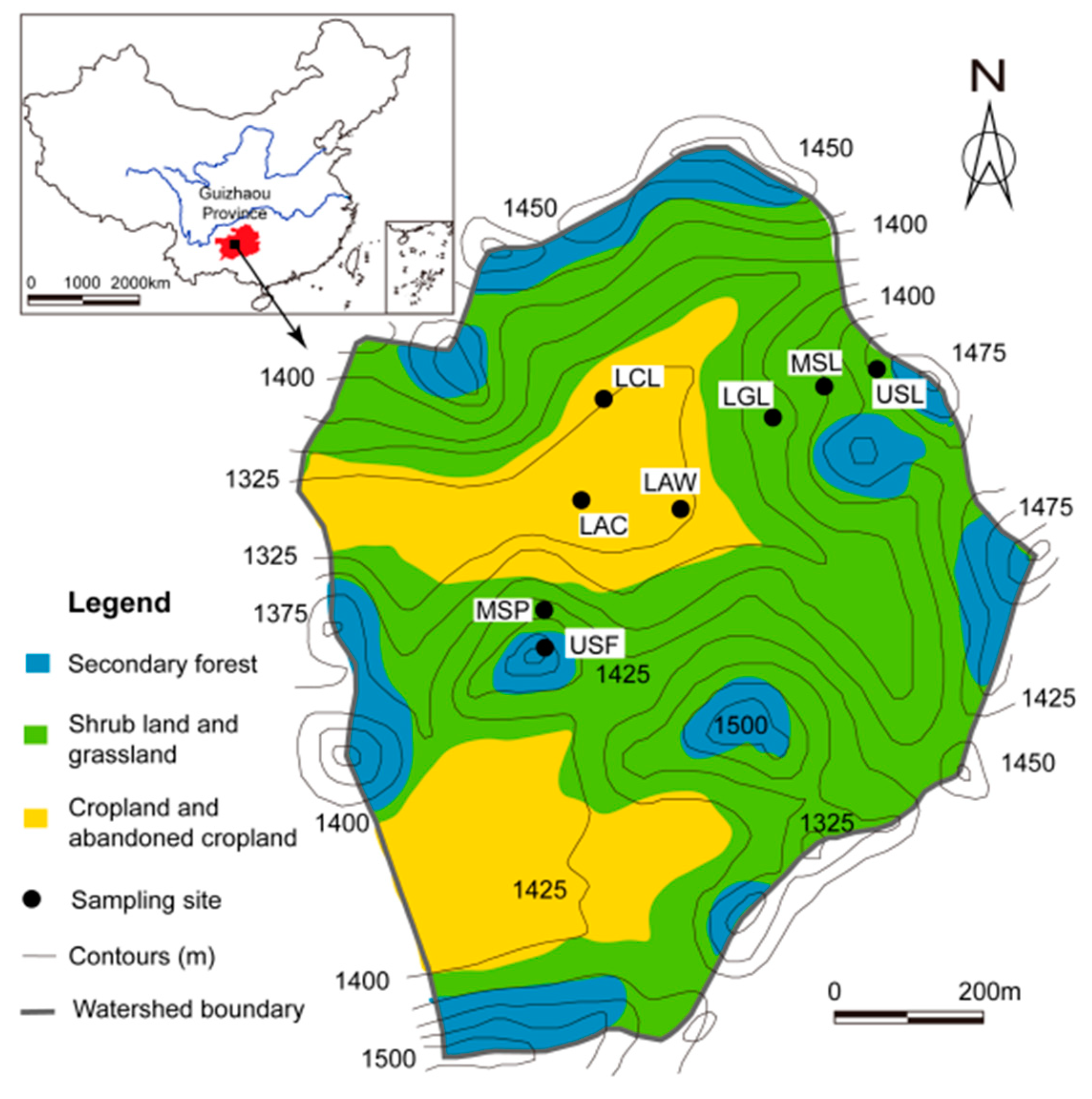

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Samples Collection and Analysis

2.3. Data Treatment

3. Results and Discussion

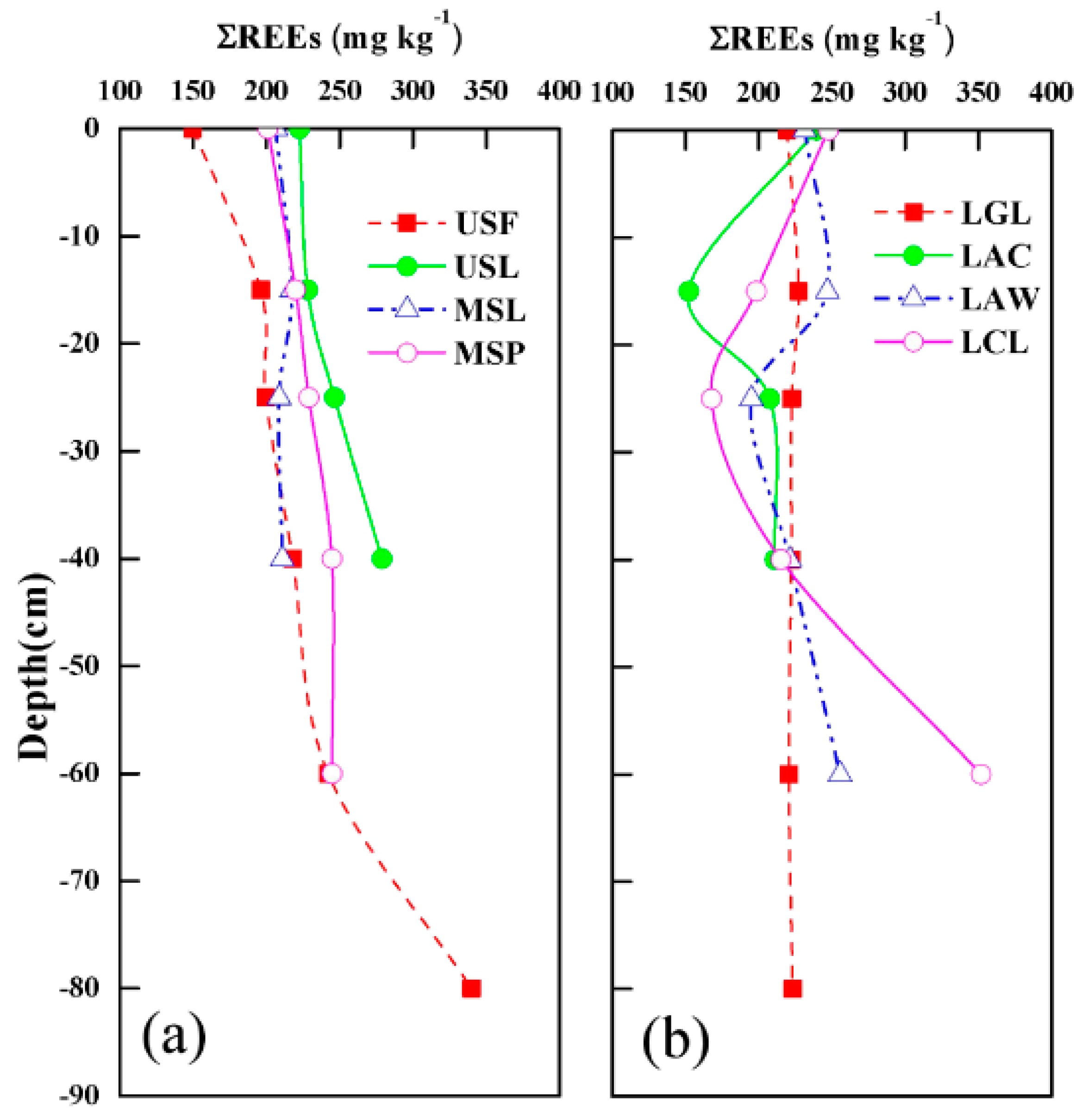

3.1. Distribution of REEs in the Soil Profile

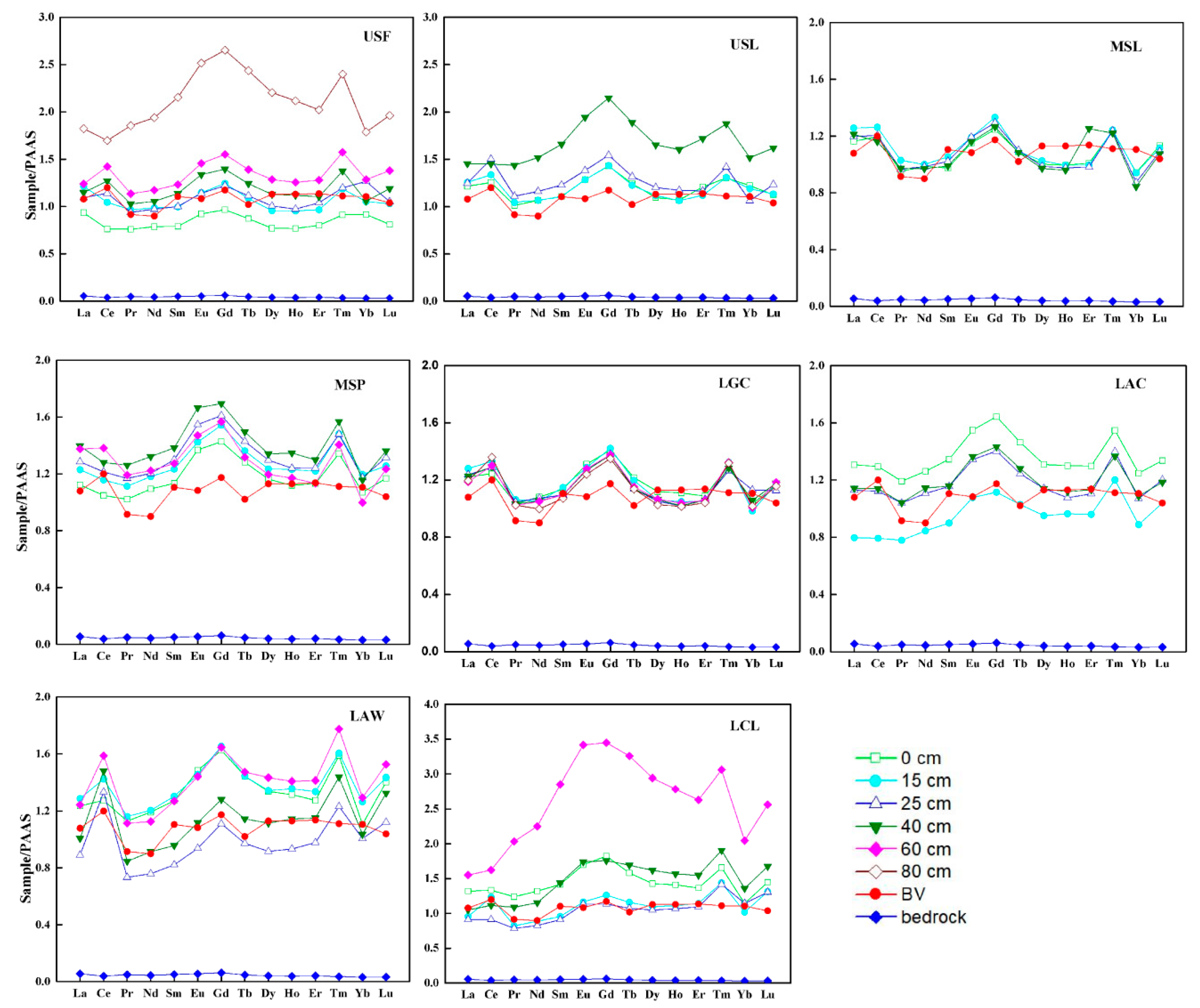

3.2. LREE/MREE/HREE Fractionation

3.3. Ce Anomalies

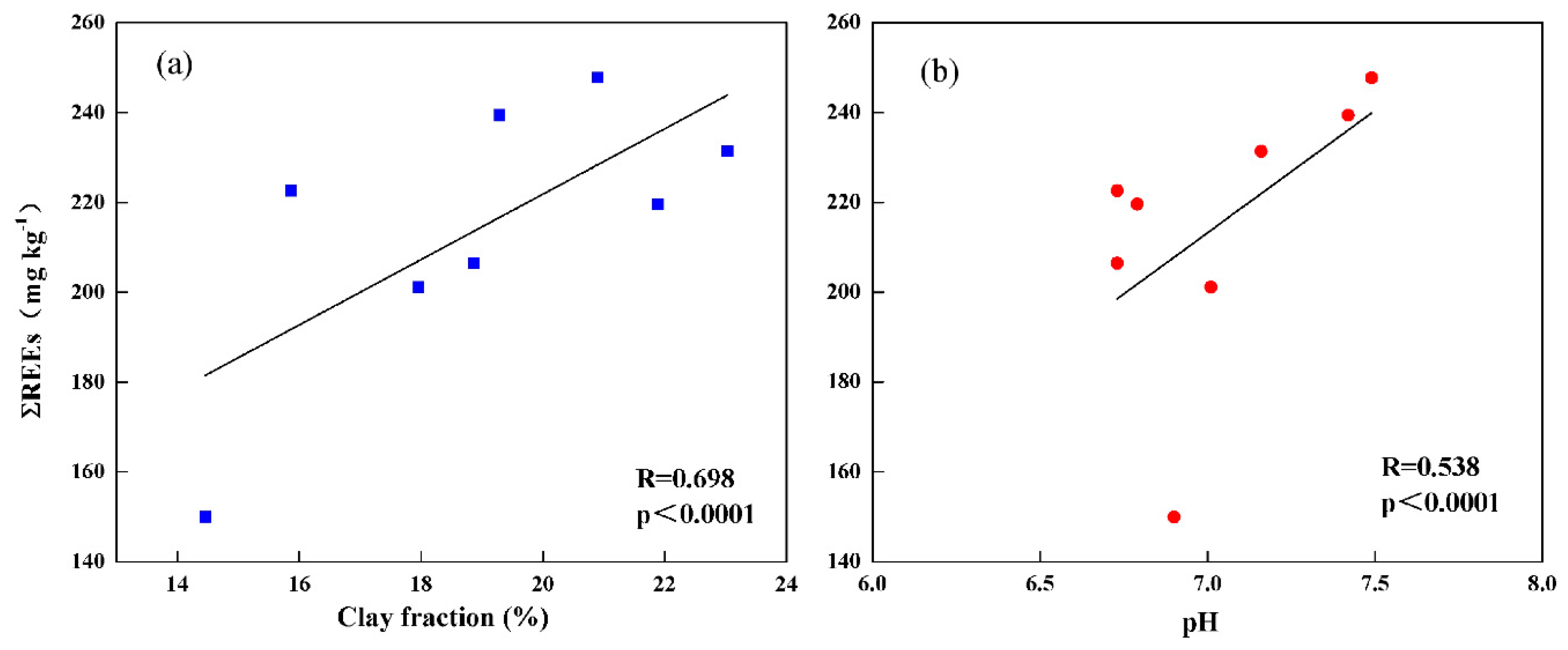

3.4. Influencing Factors for the REEs

3.4.1. Clay Content

3.4.2. Soil pH

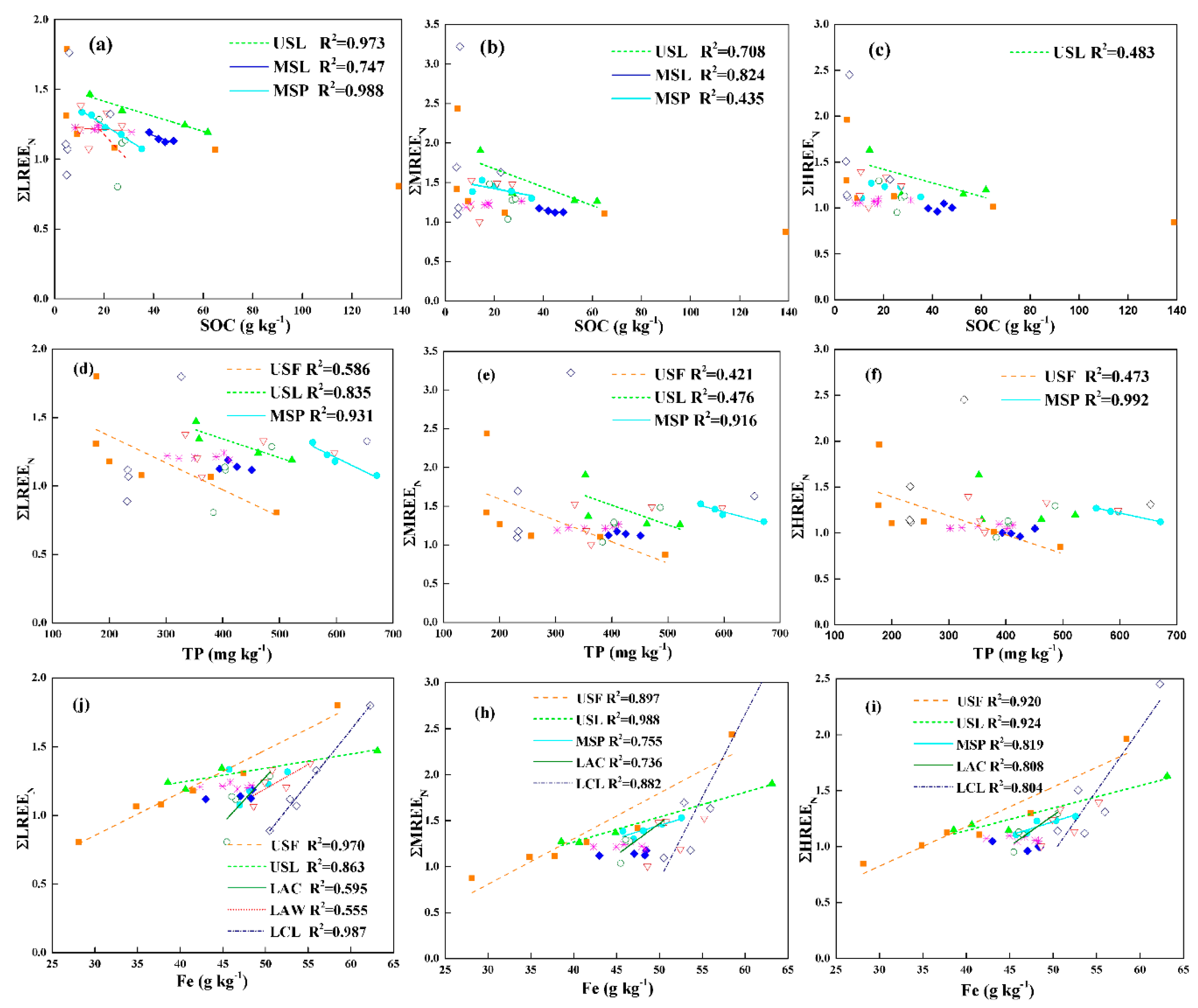

3.4.3. SOC

3.4.4. TP

3.4.5. Fe

3.5. Implication for the Transportation of Soil REEs

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The ΣREEs contents in most soils were higher than the local soil background value. The ΣREEs contents in bedrock was much lower than the level of soil layers, indicating that REEs distribution in studied soils were not mainly from bedrock.

- (2)

- The ΣREEs contents in surface soils of lower slopes sites (LGL, LAC, LAW, LCL) were higher than that of middle and upper slope sites, and the highest contents were observed in cropland (LGL). It might be related to farming activities long ago, or the nature soil erosion and movement of carriers from upper land.

- (3)

- The shale-normalized REEs pattern in soils showed MREEs significant enriched relative to LREEs and HREEs, and HREE enrichment relative to LREE. A positive Ce anomaly was found in soils, which might be related to the redox condition.

- (4)

- The clay content, pH, SOC, TP and Fe content are the main factors influencing the distribution of REEs in study areas, and SOC and Fe content showed the better linear relationship with REEs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic mean a (g kg−1) | 41.2 | 95.5 | 8.08 | 30.5 | 6.13 | 1.17 | 5.47 | 0.79 | 5.29 | 1.12 | 3.24 | 0.45 | 3.12 | 0.45 |

| Standard deviation | 13.5 | 47.3 | 3.61 | 11.9 | 2.51 | 0.521 | 2.21 | 0.361 | 1.931 | 0.385 | 1.086 | 0.126 | 0.917 | 0.124 |

| Sampling Sites | Depth (cm) | SOC (g kg−1) | Fe (g kg−1) | pH | Clay Fraction(%) | TP (mg kg−1) | Carbonate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USF | 0 | 139 | 9.6 | 6.90 | 14.5 | 495 | 0.65 |

| 15 | 64.82 | 5.1 | 7.16 | 16.6 | 379 | 0.22 | |

| 25 | 24.2 | 2.4 | 7.26 | 18.5 | 256 | 0.37 | |

| 40 | 9.22 | 1.6 | 7.57 | 20.5 | 200 | 0.36 | |

| 60 | 4.73 | 1.3 | 7.63 | 18.1 | 176 | 0.49 | |

| 80 | 5.05 | 1.5 | 7.57 | 13.2 | 178 | 0.13 | |

| USL | 0 | 61.9 | 6 | 6.73 | 15.9 | 522 | 3.32 |

| 15 | 52.6 | 5.2 | 7.01 | 13.4 | 463 | 2.67 | |

| 25 | 27.3 | 3.1 | 6.99 | 16.1 | 358 | 1.85 | |

| 40 | 14.3 | 1.6 | 7.34 | 12.7 | 353 | 1.26 | |

| MSL | 0 | 48.1 | 4.1 | 6.73 | 18.9 | 394 | 3.38 |

| 15 | 38.3 | 4.1 | 6.94 | 17.9 | 409 | 3.14 | |

| 25 | 42.0 | 4.5 | 7.13 | 19.6 | 425 | 2.81 | |

| 40 | 44.7 | 4.4 | 7.19 | 16.5 | 451 | 2.04 | |

| MSP | 0 | 35.2 | 4.1 | 7.01 | 18.0 | 671 | 1.31 |

| 15 | 27.0 | 3.5 | 7.17 | 17.6 | 598 | 0.74 | |

| 25 | 20.5 | 2.7 | 7.30 | 16.5 | 584 | 0.46 | |

| 40 | 15.0 | 2.5 | 7.33 | 16.2 | 559 | 0.76 | |

| 60 | 11.1 | 2.4 | 7.40 | 16.6 | 418 | 0.25 | |

| LGL | 0 | 31.1 | 3.8 | 6.79 | 21.9 | 412 | 2.72 |

| 15 | 17.6 | 2.7 | 6.66 | 21.4 | 402 | 1.19 | |

| 25 | 17.9 | 2.6 | 6.66 | 20.2 | 389 | 0.86 | |

| 40 | 16.1 | 2.6 | 6.38 | 21.9 | 351 | 0.89 | |

| 60 | 10.5 | 2.2 | 6.36 | 19.3 | 323 | 0.97 | |

| 80 | 8.38 | 2.1 | 6.47 | 18.3 | 302 | 0.69 | |

| LAC | 0 | 18.1 | 2.6 | 7.42 | 19.3 | 487 | 1.42 |

| 15 | 25.5 | 2.9 | 7.75 | 21.1 | 383 | 1.46 | |

| 25 | 27.3 | 3.2 | 7.67 | 18.7 | 405 | 1.61 | |

| 40 | 28.6 | 3.3 | 7.58 | 17.7 | 404 | 1.12 | |

| LAW | 0 | 27.3 | 3.5 | 7.16 | 23.0 | 597 | 0.99 |

| 15 | 21.1 | 2.9 | 7.35 | 24.6 | 472 | 0.43 | |

| 25 | 13.9 | 2.4 | 7.52 | 21.4 | 363 | 1.08 | |

| 40 | 10.2 | 2.2 | 7.40 | 21.1 | 355 | 1.44 | |

| 60 | 10.6 | 1.9 | 7.39 | 23.2 | 334 | 0.21 | |

| LCL | 0 | 22.6 | 3.2 | 7.49 | 20.9 | 654 | 1.32 |

| 15 | 5.33 | 1.8 | 7.39 | 20.6 | 234 | 0.05 | |

| 25 | 4.94 | 1.8 | 7.51 | 20.0 | 231 | 0.25 | |

| 40 | 4.58 | 1.7 | 7.34 | 19.2 | 233 | 0.67 | |

| 60 | 5.96 | 1.8 | 7.25 | 18.7 | 327 | 0.61 |

References

- Henderson, P. Rare Earth Element Geochemistry: Developments in Geochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; Volume 2, p. 510. [Google Scholar]

- Laveuf, C.; Cornu, S. A review on the potentiality of rare earth elements to trace pedogenetic processes. Geoderma 2009, 154, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.J.; Mo, D.W.; Yang, J.H.; Shi, C.X. Geochemistry of trace and rare earth elements in red soils from the Dongting lake area and its environmental significance. Pedosphere 2009, 19, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1985; p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, G. Rare earth elements in soil and plant systems—A review. Plant Soil 2004, 267, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, D.; Stille, P.; Probst, A.; Gauthier-Lafaye, F.; Pourcelot, L.; Del Nero, M. Characterization and migration of atmospheric REE in soils and surface waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 3339–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, J.; Rinklebe, J. Rare earth elements in German soils—A review. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán, E.; Fernández-Caliani, J.C.; Miras, A.; Aparicio, P.; Márquez, M.G. Residenceand fractionation of rare earth elements during kaolinization of alkaline peraluminous granites in NW Spain. Clay Miner. 2007, 42, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jun, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, C. Adsorption isotherms of lanthanum to soil constituents and effects of pH, EDTA and fulvic acid on adsorption of lanthanum onto goethite and humic acid. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2001, 13, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Johannesson, K.H. Speciation of rare earth elements in natural terrestrial waters: Assessing the role of dissolved organic matter from the modeling approach. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 2321–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.J.; Carpenter, D.; Boutin, C.; Allison, J.E. Rare earth elements (REEs): Effects on germination and growth of selected crop and native plant species. Chemosphere 2014, 96, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liang, T. Geochemical fractions of rare earth elements in soil around a mine tailing in Baotou, China. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulaksız, S.; Bau, M. Rare earth elements in the Rhine River, Germany: First case of anthropogenic lanthanum as a dissolved microcontaminant in the hydrosphere. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germund, T.; Tommy, O. Rare earth elements in forest-floor herbs as related to soil conditions and mineral nutrition. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2005, 106, 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Haneklaus, S.; Sparovek, G.; Schnug, E. Rare earth elements in soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2006, 37, 1381–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volokh, A.A.; Gorbunov, A.V.; Gundorina, S.F.; Revich, B.A.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Pal, C.S. Phosphorus-fertilizer production as a source of rare-earth elements pollution of the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 1990, 95, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D. Sensitivity of karst process to environmental change along the PEP II transect. Quat. Int. 1997, 37, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S. Effect of different land use/land cover on karst hydrogeochemistry: A paired catchment study of Chenqi and Dengzhanhe, Puding, Guizhou, SW China. J. Hydrol. 2010, 388, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, M.; Waele, J.D.; Gutierrez, F. Current perspectives on the environmental impacts and hazards in karst. Environ. Geol. 2009, 58, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianchu, X.; Fox, J.; Vogler, J.B.; Yongshou, Z.P.F.; Lixin, Y.; Jie, Q.; Leisz, S. Land-Use and Land-Cover Change and Farmer Vulnerability in Xishuangbanna Prefecture in Southwestern China. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Turner, B.L.; Geist, H.J.; Agbola, S.B.; Angelsen, A.; Bruce, J.W.; Coomes, O.T.; Dirzo, R.; Fischer, G.; Folke, C.; et al. The causes of land-use and land-cover change: Moving beyond the myths. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2001, 11, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Song, Z.; Tang, Y. Geochemistry of rare earth elements in soils under different land uses in a typical karst area, Guizhou Province, Southwest China. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 97, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Li, F.; Tang, Y. Organic matter impact on distribution of rare earth elements in soil under different land uses. CLEAN–Soil Air Water 2017, 45, 1600235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Han, G.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Z. Variations and indications of δ 13C SOC and δ 15N SON in soil profiles in Karst Critical Zone Observatory (CZO), southwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Han, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, T.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Song, Z. Effects of slope position and land use on the stability of aggregate-associated organic carbon in calcareous soils. Acta Geochim. 2017, 36, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Environmental Monitoring Station. Background Values of Element in Soil of China; Chinese Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990; pp. 418–451. [Google Scholar]

- Midwood, A.J.; Boutton, T.W. Soil carbonate decomposition by acid has little effect on δ 13C of organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xiao, H.; Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, G. An indirect method for determination of soil total carbonate. Soils 2006, 38, 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Han, G.; Liu, M.; Liang, T. Spatial distribution and controlling factors of heavy metals in soils from Puding Karst Critical Zone Observatory, southwest China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S. Rare earth elements in sedimentary rocks; influence of provenance and sedimentary processes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 1989, 21, 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sholkovitz, E.R.; Landing, W.M.; Lewis, B.L. Ocean particle chemistry: The fractionation of rare earth elements between suspended particles and seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Xu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, G. Rare Earth Element Patterns in the Karst Terrains of Guizhou Province, China: Implication for Water/Particle Interaction. Aquat. Geochem. 2009, 15, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z. Weathering and Pedogenesis of Karst Catchment, Behavior of Mineral Elements and Environmental Quality; Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences Press: Guizhou, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duddy, L.R. Redistribution and fractionation of rare-earth and other elements in a weathering profile. Chem. Geol. 1980, 30, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne Nesbitt, H.; Markovics, G. Weathering of granodioritic crust, long-term storage of elements in weathering profiles, and petrogenesis of siliciclastic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1997, 61, 1653–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y. Rare earth element distribution in weathering crusts of carbonte rocks, Guizhou Province. Carsol. Sin. 1998, 17, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Johannesson, K.H. Ligand extraction of rare earth elements from aquifer sediments: Implications for rare earth element complexation with organic matter in natural waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 6690–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wei, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Cerium Anomalies in Supergene Geological Bodies and Its Effecting Factors. Chin. Rare Earths 2007, 28, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, W.; Tan, H.; Jiang, S.; Chen, J. Trace element and REE geochemistry of fine- and coarse-grained sands in the Ordos deserts and links with sediments in surrounding areas. Geochemistry 2011, 71, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimoto, A.; Nearing, M.A.; Zhang, X.C.; Powell, D.M. Applicability of rare earth element oxides as a sediment tracer for coarse-textured soils. Catena 2006, 65, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S.; Tsumura, A. Adsorption and Desorption of Exogenous Rare Earth Elements in Soils: I. Rate and Forms of Rare Earth Elements Sorbed. Pedosphere 1993, 3, 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, X. Effects of redox potential and pH value on the release of rare earth elements from soil. Chemosphere 2001, 44, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davranche, M.; Gruau, G.; Dia, A.; Marsac, R.; Pédrot, M.; Pourret, O. Biogeochemical Factors Affecting Rare Earth Element Distribution in Shallow Wetland Groundwater. Aquat. Geochem. 2015, 21, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhlander, B.; Land, M.; Ingri, J.; Widerlund, A. Mobility of rare earth elements during weathering of till in northern Sweden. Appl. Geochem. 1996, 11, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.K. Research advances in the behavior and fate of rare earth elements in soil-plant systems. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2005, 24 (Suppl. 1), 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Song, W.; Wang, L.; Kleinman, P.J.A.; Cao, H. Interactions between exogenous rare earth elements and phosphorus leaching in packed soil columns. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.H.; Liu, X.W.; Schjf, J. The influence of phosphate coprecipitation on rare earth distributions in natural waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 3341–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grawunder, A.; Lonschinski, M.; Merten, D.; Büchel, G. Distribution and bonding of residual contamination in glacial sediments at the former uranium mining leaching heap of Gessen/Thuringia, Germany. Chem. der Erde 2009, 69 (Suppl. 2), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Site | Slope Position | Land-Use Types | Elevation (m) | Land-Use Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USF | Upper slope | Secondary forest land | 1442 | The virgin forest land had been deforested and evolved to secondary forest land for over 50 years |

| USL | Upper slope | Shrub land | 1425 | Natural evolution |

| MSL | Middle slope | Shrub land | 1404 | Natural evolution |

| MSP | Middle slope | Shrub land | 1385 | The pear orchard land had been abandoned and evolved to shrub land for over eight years |

| LGL | Lower slope | Grassland | 1376 | The cropland had been abandoned and evolved to grassland for five years |

| LAC | Lower slope | Abandoned cropland | 1335 | The cropland had been abandoned and covered by weed. for two years |

| LAW | Lower slope | Abandoned cropland | 1333 | The cropland had been abandoned for two years |

| LCL | Lower slope | Cropland | 1335 | The crop rotation and ploughed fallow had been for more than 50 years, and manure and fertilizer had been used |

| Sampling Sites | Depth (cm) | ΣREEs (mg kg−1) | (La/Yb)N | (La/Gd)N | (Gd/Yb)N | δCe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USF | 0 | 145 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.90 |

| 15 | 197 | 1.15 | 0.98 | 1.18 | 0.96 | |

| 25 | 200 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 1.12 | |

| 40 | 218 | 1.08 | 0.82 | 1.32 | 1.17 | |

| 60 | 242 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 1.21 | 1.20 | |

| 80 | 340 | 1.02 | 0.69 | 1.48 | 0.92 | |

| USL | 0 | 223 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 1.17 | 1.13 |

| 15 | 228 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 1.20 | 1.16 | |

| 25 | 247 | 1.18 | 0.81 | 1.45 | 1.27 | |

| 40 | 279 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.42 | 1.00 | |

| MSL | 0 | 207 | 1.23 | 0.93 | 1.32 | 1.13 |

| 15 | 217 | 1.34 | 0.94 | 1.42 | 1.10 | |

| 25 | 209 | 1.37 | 0.93 | 1.48 | 1.11 | |

| 40 | 206 | 1.44 | 0.96 | 1.50 | 1.06 | |

| MSP | 0 | 201 | 1.05 | 0.79 | 1.33 | 0.98 |

| 15 | 220 | 1.03 | 0.80 | 1.29 | 0.99 | |

| 25 | 229 | 1.10 | 0.80 | 1.37 | 0.99 | |

| 40 | 245 | 1.21 | 0.82 | 1.47 | 0.96 | |

| 60 | 245 | 1.38 | 0.88 | 1.57 | 1.08 | |

| LGL | 0 | 220 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 1.37 | 1.10 |

| 15 | 227 | 1.30 | 0.90 | 1.45 | 1.14 | |

| 25 | 223 | 1.09 | 0.90 | 1.22 | 1.13 | |

| 40 | 222 | 1.16 | 0.89 | 1.30 | 1.14 | |

| 60 | 221 | 1.18 | 0.86 | 1.37 | 1.18 | |

| 80 | 223 | 1.18 | 0.89 | 1.33 | 1.22 | |

| LAC | 0 | 239 | 1.05 | 0.79 | 1.32 | 1.04 |

| 15 | 152 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 1.26 | 1.01 | |

| 25 | 208 | 1.06 | 0.81 | 1.31 | 1.04 | |

| 40 | 211 | 1.05 | 0.80 | 1.32 | 1.04 | |

| LAW | 0 | 231 | 1.12 | 0.76 | 1.47 | 1.08 |

| 15 | 247 | 1.02 | 0.78 | 1.31 | 1.16 | |

| 25 | 195 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 1.64 | |

| 40 | 221 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 1.24 | 1.60 | |

| 60 | 256 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 1.27 | 1.35 | |

| LCL | 0 | 248 | 1.15 | 0.72 | 1.59 | 1.04 |

| 15 | 199 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 1.24 | 1.39 | |

| 25 | 168 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 1.07 | |

| 40 | 215 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 1.29 | 1.04 | |

| 60 | 352. | 0.76 | 0.45 | 1.69 | 0.91 | |

| bedrock | 8.05 | 1.77 | 0.90 | 1.98 | 0.75 | |

| BV | 203 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 1.06 | 1.20 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Han, G.; Liu, M.; Wang, L. Geochemical Characteristics of Rare Earth Elements in Soils from Puding Karst Critical Zone Observatory, Southwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184963

Zhang Q, Han G, Liu M, Wang L. Geochemical Characteristics of Rare Earth Elements in Soils from Puding Karst Critical Zone Observatory, Southwest China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184963

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qian, Guilin Han, Man Liu, and Lingqing Wang. 2019. "Geochemical Characteristics of Rare Earth Elements in Soils from Puding Karst Critical Zone Observatory, Southwest China" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184963

APA StyleZhang, Q., Han, G., Liu, M., & Wang, L. (2019). Geochemical Characteristics of Rare Earth Elements in Soils from Puding Karst Critical Zone Observatory, Southwest China. Sustainability, 11(18), 4963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184963