Optimization of Crude Palm Oil Fund to Support Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting in Reducing Deforestation in Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Smallholders Contribution to National Palm Oil Production: Importance and Challenges

3.1.1. Palm oil as Indonesia’s Strategic Commodity

3.1.2. Challenges in the Palm Oil Sector in Indonesia

3.2. CPO Fund Policy: Implementation Challenges

3.2.1. Legal Basis

3.2.2. How Easy Is It for Smallholders to Receive Financing from the CPO Fund?

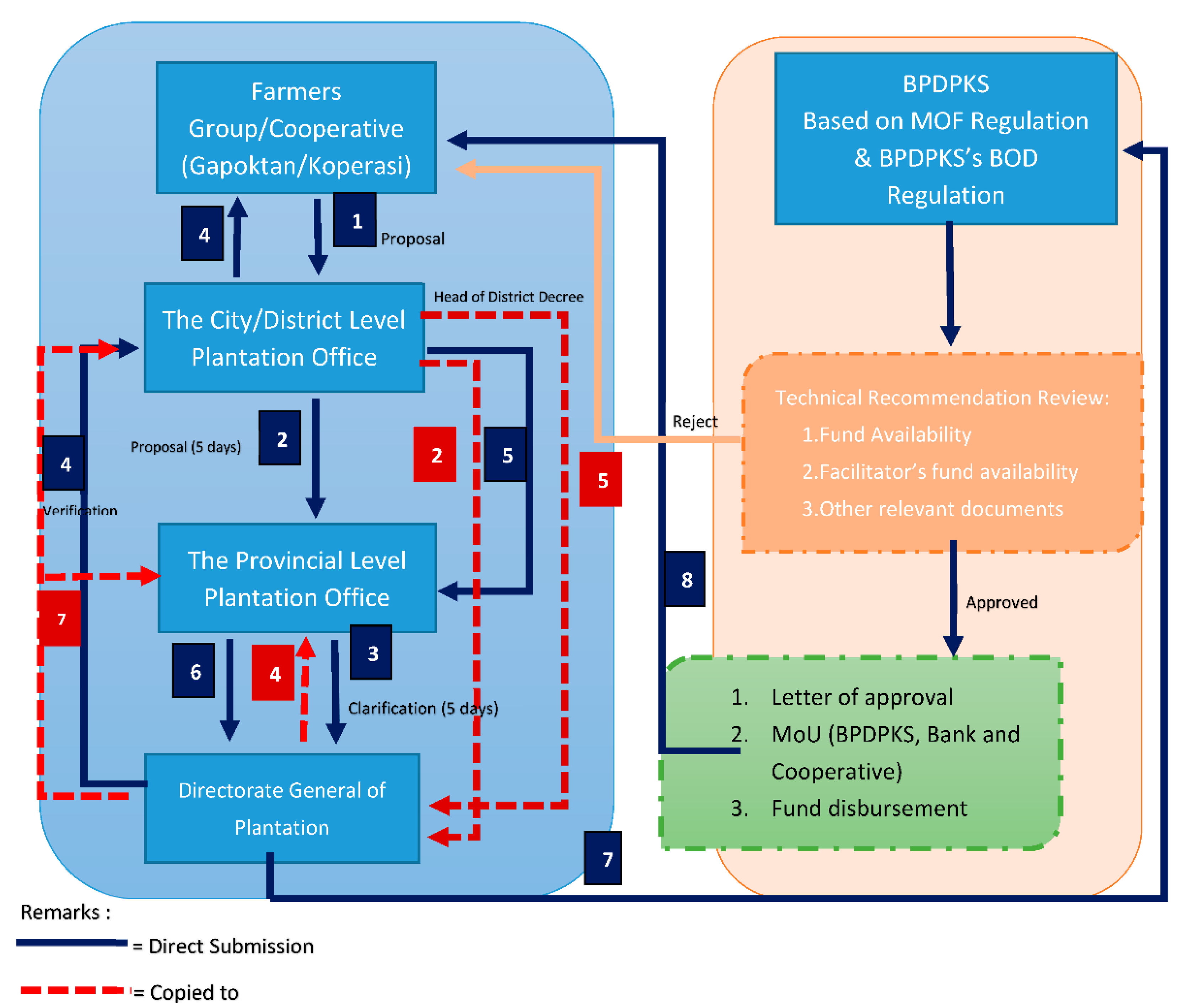

- Farmer groups submit replanting proposals, once they are considered to meet administrative requirements, to the district plantation office for verification.

- The district plantation office verifies the proposals and recapitulates received proposals from farmers across district, and submits them to the provincial plantation offices, copied to the Director General of Plantations.

- The provincial plantation office submits verification results to Director General of Plantations.

- Director General of Plantations verifies all replanting proposals and resubmit verification results to the district plantation office, copied to the provincial plantation office. Once proposals are verified and considered to meet the requirements, the Head of district plantation office on behalf of the regent issues a decree determining prospective farmers and potential lands (CPCL) that are eligible for replanting funds. District plantation office delivers results of verification by the Director General of Plantation to the farmer group/cooperative proposer.

- District plantation office submits CPCL decrees to the provincial plantation office, copied to the Director General of Plantations.

- The provincial plantation office submits the verified CPCL decree to Director General of Plantations who will re-verifies relevant documents and conducts ground checks, if necessary.

- Based on the verification results, the Director General of Plantation provides BPDPKS with technical recommendations, copied to both provincial and district plantation offices.

- BPDPKS reviews technical recommendations and make decisions on those who are eligible to receive replanting funds, and issues a letter of approval, facilitates and disburses funds directly to targeted farmer groups through the Banks, according to stages of replanting activities.

3.3. Policy Options to Optimize the CPO Fund to Support Smallholder Planting and Reduce Deforestation

3.3.1. Strengthening the Implementation of Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting Policies

3.3.2. Financial Support to Legalize Smallholder Lands

3.3.3. The Allocation of Oil Palm Funds in Relation to Grace Periods after Replanting

3.3.4. Adjustment of Replanting Costs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pacheco, P.; Gnych, S.; Darmawan, A.; Komarudin, H.; Okarda, B. The Palm Oil Global Value Chain: Implications for Economic Growth and Social and Environmental Sustainability; Working Paper 220; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General of Plantation. Tree Crop Estate Statistics of Indonesia 2016–2018; Ministry of Agriculture: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Komitmen Perbaikan Sawit Indonesia; Rembug Nasional Pertani Kelapa Sawit Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 28 November 2018.

- Rival, A.; Levang, P. Palms of Controversies: Oil Palm and Development Challenges; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette, J.F. Is Oil Palm Agribussiness a Sustainable Development for Indonesia? A Review of Issues and Options. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 37, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, J.; Wang, J.; Hooijer, A.; Liew, S. Peatland Conversion and Degradation Processes in Insular Southeast Asia: A Case Study in Jambi, Indonesia. Land Degrad. Dev. 2013, 24, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, L.P.; Wilcove, D.S. Is Oil Palm Agriculture Really Destroying Tropical Biodiversity? Conserv. Lett. 2008, 1, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savilaakso, S.; Garcia, C.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Ghazoul, J.; Groom, M.; Guariguata, M.R.; Laumonier, Y.; Nasi, R.; Petrokofsky, G.; Snaddon, J.; et al. Systematic Review of Effects on Biodiversity from Oil Palm Production; Occasional Paper No. 116; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gunarso, P.; Hartoyo, M.E.; Nugroho, Y. Analisis Penutupan Lahan Dan Perubahannya Menjadi Kelapa Sawit Di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Di 5 Pulau Besar Di Indonesia Periode 1990 s.d 2010. J. Green Growth Dan Manaj. Lingkung. 2013, 1, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, K.G.; Mosnier, A.; Pirker, J.; McCallum, I.; Fritz, S.; Kasibhatla, P.S. Shifting Patterns of Oil Palm Driven Deforestation in Indonesia and Implications for Zero-Deforestation Commitments. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.H.; Abood, S.; Ghazoul, J.; Barus, B.; Obidzinski, K.; Koh, L.P. Environmental Impacts of Large-Scale Oil Palm Enterprises Exceed That of Smallholdings in Indonesia. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 7, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoneveld, G.C.; Jelsma, I.; Komarudin, H.; Andrianto, A.; Okarda, B.; Ekowati, D. Public and Private Sustainability Standards in the Oil Palm Sector: Compliance Barriers Facing Indonesia’s Independent Oil Palm Smallholders; Info Brief No. 182; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General of Plantation. Dukungan Pendanaan Bagi Peningkatan Produktivitas Kelapa Sawit Nasional Serta Peningkatan Kesejahteraan Kelapa Sawit; USAID-Governing Oil Palm Landscapes for Sustainability (GOLS) Project Focus Group Discussion: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, A.; Mafira, T.; Sutiyono, G. Improving Land Productivity through Fiscal Policy: Early Insights on Taxation in the Palm Oil Supply Chain; Climate Policy Initiative (CPI): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sahara, H.; Kusumowardhani, N. Smallholder Finance in the Palm Oil Sector. Analyzing the Gaps between Existing Credit Schemes and Smallholder Realities; Infobrief no. 185; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alforte, A.; Matias, D.; Munden, L.; Perron, J. Financing Sustainable Agriculture and Mitigation: Smallholders and the Landscape Fund; Working Paper 52; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst, E.; Cavallo, E.; Medler, M.; Klinghammer, S.; Smit, H.; Gijsenbergh, A.; Laan, C. Current Practices and Innovations in Smallholder Palm Oil Finance in Indonesia and Malaysia: Long-Term Financing Solutions to Promote Sustainable Supply Chains; Occasional Paper 177; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.H.; Rist, L.; Obidzinski, K.; Ghazoul, J.; Koh, L.P. No Farmer Left behind in Sustainable Biofuel Production. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 2512–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, N.; Gelder, J.W.V.; Smit, H.; Pacheco, P.; Gnych, S. How Can the Financial Services Sector Strengthen the Sustainability and Inclusivity of Smallholder Farming in the Supply of Global Commodity Crops; White Paper; Global Landscape Forum: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, R.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; Hariyadi, M.A.; Purwawangsa, H.; Ginting, G. Reducing Agricultural Expansion into Forests in Central Kalimantan Indonesia: Analysis of Implementation and Financing Gaps; Institut Pertanian Bogor: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, V. Palm Oil’s Big Issue: Smallholders. Available online: http://www.eco-business.com/news/palm-oils-big-issue-smallholders/ (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Cavallo, E. Innovative Approaches for Oil Palm Smallholder Finance in Malaysia and Indonesia; International Ssustainability Carbon Certification (ISCC): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mariyah Syaukat, Y.; Hartoyo, S.; Fariyanti, A.; Krisnamurthi, B. The Role of Farm Household Saving for Oil Palm Replanting at Paser Regency, East Kalimantan. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2018, 8, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, D.; Smit, H.H.; Bronkhorst, E.; Medler, M.V.D.T.; Adjaffon, I.; Cavallo, E. Innovative Replanting Financing Models for Oil Palm Smallholder Farmers in Indonesia: Potential for Upscaling, Improving Livelihoods and Supporting Deforestation-Free Supply Chains; The Tropical Forest Alliance (TFA): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations General Assembly, Development and International Co-operation: Oslo, Norway, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R.; Bhatia, S. Palm Oil: Addressing Issues and towards Sustainable Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 13, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. Economics of the Public Sector, 3rd ed.; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barde, J.P. Environmental Policy and Policy Instruments. In Principles of Environmental and Resource Economics: A Guide for Students and Decision Makers; Folmer, H., Gabel, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giger, M.; Liniger, H.; Critchley, W. Use of Incentives and Profitability of Soil and Water Conservation (SWC) in Eastern and Southern Africa. In Sanders D, et al. 1999: Incentives in Soil Conservation; Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Enters, T. Incentives as Policy Instruments: Key Concepts and Definitions. In Incentives in Soil Conservation; Sanders, D.W., Huszar, P.C., Sombatpanit, S., Enters, T., Eds.; Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Comerford, E.; Jim, B. Choosing between Incentive Mechanisms for Natural Resource Management: A Practical Guide for Regional NRM Bodies in Queensland; Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy: Brisbane, Australia, 2004.

- Arifin, B. Ekonomi Pembangunan Pedesaan; IPB Press: Bogor, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nurrochmat, D. Telaah Kerangka Infrastruktur Dan Mekanisme Pengelolaan Hutan Berkelanjutan (SFM) Sebagai Opsi Penting Dalam Penurunan Emisi Dari Deforestasi Dan Degradasi Hutan (REDD); Kementerian Kehutanan RI dan ITTO: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2011.

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design Qualitative & Quantitative Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: California, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, W.N. Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting Them Together into Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfatriani, F.; Darusman, D.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; Yustika, A.E.; Muttaqin, M. Redesigning Indonesian Forest Fiscal Policy to Support Forest Conservation. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 61, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomm, M. Gap Analysis: Methodology, Tool and First Application; Universitat Hagen: Darmstadt, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Koordinator Perekonomian. Latar Belakang Pembentukan BPDP Kelapa Sawit; Universitas Muhammadiyah Jogjakarta: Jogjakarta, Indonesia, 2018.

- Nurfatriani, F.; Ramawati Sari, G.K.; Komarudin, K. Optimalisasi Dana Sawit Dan Pengaturan Instrumen Fiskal Penggunaan Lahan Hutan Untuk Perkebunan Dalam Upaya Mengurangi Deforestasi; Working Paper 238; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Susila, W.R. Contribution of Oil Palm Industry to Economic Growth and Poverty Alleviation in Indonesia. Agric. R D 2004, 23, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Syahza, A. Percepatan Ekonomi Pedesaan Melalui Pembangunan Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit. J. Ekon. Pembang. 2011, 2, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.K.; Ruesch, A.S.; Achard, F.; Clayton, M.K.; Holmgren, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Tropical Forests Were the Primary Sources of New Agricultural Land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16732–16737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BPDPKS. Replanting Financial Model for Smallholders Farmers to Increase Productivity and Welfare; Oil Palm Plantation Fund Management Agency (BPDPKS): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017.

- SPKS. Tantangan Dan Peluang Dukungan Dana Sawit Bagi Pengelolaan Sawit Berkelanjutan Dan Peningkatan Kesejahteraan Petani Sawit; USAID-Governing Oil Palm Landscapes for Sustainability (GOLS) Project Focus Group Discussion: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dinas Perkebunan Provinsi Kalimantan Barat. Peluang Dan Tantangan Pemanfaatan Dana Sawit Untuk Peremajaan Sawit Rakyat Di Kalimantan Barat; USAID-Governing Oil Palm Landscapes for Sustainability (GOLS) Project Workshop, Pontianak: West Kalimantan, Indonesia, 2018.

- Dinas Perkebunan Provinsi Kalimantan Tengah. Peluang Dan Tantangan Pemanfaatan Dana Peremajaan Sawit Rakyat Di Kalimantan Tengah; USAID-Governing Oil Palm Landscapes for Sustainability (GOLS) Project Workshop, Palangkaraya: Central Kalimantan, Indonesia, 2018.

- Hellin, J.; Schrader, K. The Case against Direct Incentives and the Search for Alternative Approaches to Better Land Management in Central America. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 99, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OJK. Roadmap Keuangan Berkelanjutan Di Indonesia 2015–2019; Otoritas Jasa Keuangan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014.

- Jelsma, J.; Schoneveld, G.C. Towards More Sustainable and Productive Independent Oil Palm Smallholders in Indonesia: Insights from the Development of a Smallholder Typology; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sawit Indonesi. Ini Prasyarat KUR Khusus Peremajaan Sawit Dengan Bunga 7%. Available online: https://sawitindonesia.com/rubrikasi-majalah/berita-terbaru/ini-prasyarat-kur-khusus-peremajaan-sawitdengan-bunga-7/ (accessed on 28 November 2017).

- PT.GAR. Program Inovasi Pembiayaan Sebagai Rancangan Insentif Ekonomi Untuk Petani Swadaya; USAID-Governing Oil Palm Landscapes for Sustainability (GOLS) Project Focus Group Discussion: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Objectives | Theory Used | Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| To analyze the optimization of the CPO fund to support sustainable oil palm management, particularly for strengthening smallholders in the palm oil industry | Public policy [35] Sustainable development [25,36] Incentives [29,30] and incentive-based natural resources management policy [27,28,32] | Gap policy analysis |

| No. | Legal Basis | Content | Implementation | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Law of The Republic of Indonesia No. 39/2014 on Plantations | Financing plantation business carried out by business actors, including companies and smallholders, sourced from business actors, financial institutions, public funds, and other legitimate funds (article 93 paragraph 3). Fund collected shall be used for developing human resources, research and development, promotion, smallholder replanting, and infrastructure development. | Funds collected take the form of the CPO fund, which has been used for designated allocations. However, some portions have also been allocated for other uses such as for food needs, downstream industries and biodiesel, which are not specified in this law. | Disharmony in regulations between Plantations Law No. 39/2014 and Presidential Regulation No. 61/2015 |

| 2 | Republic of Indonesia Government Regulation No. 24/2015 on Plantation Fundraising | Funds collected from plantation business actors comprise levies on exported CPO and dues (article 5 paragraph 1). | Thus far, funds that have been collected are only levies on exported CPO. | The absence of dues from the plantation business operator |

| 3 | Presidential Regulation No. 61/2015 on Collection and use of CPO fund (as revised by Presidential Regulation No. 24/2016) | Plantation fund source from levies on CPO exported and/or its derivatives and dues (article 3, paragraph 1). This regulation governs the use of plantation funds, particularly levies on exported CPO, for other uses such as food, downstream industries, and biodiesel. | Larger portion of funds is allocated to biodiesel incentive (80–90%) than to those allocated for financing smallholder replanting (1%). | Disharmony in regulations between Plantations Law No. 39/2014 and Presidential Regulation No. 61/2015 |

| 4 | Minister of Finance Regulation (PMK) No. 133/PMK.05/2015 on tariff charged on services provided by CPO Fund Agency | Tariffs consist of levies and dues. CPO funds take the form of levies on exported CPO, and/or their derivative products (article 2). Dues are charged only to companies, not smallholders (article 8). The rate of tariff ranges from USD 20 to USD 50 per ton of CPO or its derivative products. | Levies have been collected based on this regulation. However, dues have not been implemented. Based on Finance Minister’s regulation No. 13/2017, export duty will only be charged if the CPO price is above USD 750/ton. | Potential loss of state revenues from export duties when CPO price is below USD 750 |

| 5. | PMK No. 113/PMK.01/2015 on CPO Fund Agency Organization and Work Procedure | CPO Fund Agency is an organizational unit under the Directorate General of Treasury, Ministry of Finance, responsible for the collection, management and distribution of the CPO fund (articles 1, 2 and 3). | The agency merely plays a role in distributing and disbursing fund. Disbursement of funds for smallholder replanting highly depends on technical recommendation from Directorate General of Plantation, Ministry of Agriculture. | Distribution of funds to support replanting is hindered by lack of implementing institution performance |

| 6 | Minister of Finance Regulation (PMK) No. 152/PMK.05/2018 on tariff charged on services provided by CPO Fund Agency | Amending the above-mentioned PMK No. 133/PMK.05/2015, the rate of tariff changes to USD 0 per ton of CPO if the CPO price is below USD 570 per ton. The tariff will be charged USD 25 per ton of CPO or its derivative products, if the CPO price ranges from USD 570 to USD 619. The rate of tariff charged is USD 50 per ton of CPO if the CPO price is above USD 619. | Due to the decline in CPO prices, the government issued this regulation in December 2018. Since then, the CPO price was lower than USD 570, and therefore no tariff has been charged. | Potential loss of revenues from CPO fund |

| Indicator | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Land | Uncertified | Certified |

| Fund | Commercial interest | Subsidized interest |

| Seeds | Uncertified | Certified and have a certain quality |

| Production | 2–3 tons CPO/ha/year | 5–6 tons CPO/ha/year |

| Land expansion | Tend to expand land to forest | Not expanding to the forest |

| Sustainability | ISPO uncertified | ISPO certified |

| Grace period assistance | No source of income in grace period | A source of income is available during the grace period |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nurfatriani, F.; Ramawati; Sari, G.K.; Komarudin, H. Optimization of Crude Palm Oil Fund to Support Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting in Reducing Deforestation in Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184914

Nurfatriani F, Ramawati, Sari GK, Komarudin H. Optimization of Crude Palm Oil Fund to Support Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting in Reducing Deforestation in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):4914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184914

Chicago/Turabian StyleNurfatriani, Fitri, Ramawati, Galih Kartika Sari, and Heru Komarudin. 2019. "Optimization of Crude Palm Oil Fund to Support Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting in Reducing Deforestation in Indonesia" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 4914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184914

APA StyleNurfatriani, F., Ramawati, Sari, G. K., & Komarudin, H. (2019). Optimization of Crude Palm Oil Fund to Support Smallholder Oil Palm Replanting in Reducing Deforestation in Indonesia. Sustainability, 11(18), 4914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184914