Abstract

In this study, we explore the recognition of publicness as understood by everyday users of public space. By analyzing news articles in South Korea selected from 1 January 2010, to 31 December 2018, this study examines a discourse which is largely missing in the existing studies—the subjective experience and framing of contemporary spatial publicness by its end-users. After analyzing the contents from a total of 583 articles in the KINDS database, we develop a general typology of how contemporary spatial publicness is represented in South Korea. Although the scope and background of questions surrounding South Korea’s recognition of contemporary spatial publicness are different from that of Western countries, a similar debate has emerged about what publicness means in the context of the architecture and urban space around the globe. By developing different thematic dimensions in the representations of contemporary spatial publicness, we further discuss the implications for future research to examine the pragmatic sensibilities of individuals and utility of semi-public/private space.

1. Introduction

Traditional boundaries of public and private spaces are becoming increasingly ambiguous [1,2,3]. Direct provision of services (i.e., management) by the public sector is being replaced by various hybrid schemes between the public and private sectors. This transition raised questions regarding the conceptualization of contemporary publicness of space. When faced with the question, “what is the concept of contemporary publicness on space?”, the answer is seldom clear. The problem is that there is no universal pragmatic definition of traditional publicness among various academic fields. Publicness is defined in a slightly different sense in each area and is largely defined by abstract and nebulous definitions that do not convey clear distinctions [3,4].

A similar problem exists in the academic discourse on urban and architectural space. Use of the term “publicness” in relation to contemporary public space is also not yet an established terminology in the academic discourse [5]. Rather than to conceptualize publicness as a utilitarian tool, contemporary public spaces are far too often emphasized for their neoliberal qualities [6,7,8]. The existing scholarship on contemporary spatial publicness can be largely divided into the following content: (1) specific spatial characteristics such as evaluation model; and (2) public space as a site of politics such as equality, democracy, and inclusion that maintains publicness based on the identities of end users. These two main bodies of literature both have limitations. The first limitation is the tendency in the existing research to replicate and reproduce the same characteristics as legitimate evaluative criteria, falling short of incorporating how end-users experience and utilize public spaces. The second limitation is the lack of significant academic consideration of agency exercised in the public sphere. Individuals are not simply automatons without pragmatic sensibilities [9,10,11]. Above all, the discourse on the concept of publicness of space might wane, were it not always possible to update it under new conditions. Going into the intricacies of publicness theory, this study attempts an exploration of the variety of spatial publicness characteristics emerging in the contemporary city.

We contend that publicness as conceptualized by existing studies of public space lacks in-depth research on the subjective perception of publicness, which is paramount to understanding how public spaces are used, understood, and experienced by its everyday end-user. Yang [12]’s notion of “spatial publicness” is useful here to overcome the deficiencies in the existing conceptual frameworks, especially considering the complexity, fluidity, and multiplicity of modern urban phenomena in relation to publicness.

Through a dimensional understanding of diversity and heterogeneity in the use of the term “publicness”, we define and delineate the spatiality of what is authentically considered, or more precisely, what is more attuned to publicness to investigate the characteristics of contemporary urban and architectural spaces. Hence, the purpose of this study is to explore and define the concept of contemporary spatial publicness and, subsequently, to find ways to apply it to practical usages. In considering these contexts that fragment publicness, its utilization and interpretation in the academic discourse, we attempt to explore a subjective perspective beyond the view point of academic expertise by examining how spatial publicness is represented in the media.

We focused on South Korea as the mainstream communicative discourse such as news media outlets often use the term publicness more institutionally compared to other nation-states [13]. Since 1980s, South Korea has continuously developed robust social policies and institutions to facilitate the publicness of urban and architectural spaces. In 2008, South Korea newly enacted the Framework Act on Construction. Through this, spatial publicness is emphasized in the institutional aspect as well, with the realization of the architectural spatial, social, and cultural public character as the basic direction of architectural policy. In this context, spatial publicness in South Korea has been emphasized in terms of institutional and practical aspects. Juridical-political structures shaped the rights of social and cultural spatial publicness, which directly influenced architectural policies in South Korea.

By analyzing contents from news articles in South Korea selected from 1 January 2010, to 31 December 2018, we develop a general typology of how contemporary spatial publicness is represented in South Korea. Although South Korea’s recognition of contemporary spatial publicness is different from that of other countries, a similar debate has emerged about what publicness means in the context of architecture and urban space globally. We also derive new characteristics of contemporary spatial publicness by analyzing and condensing the existing narratives and discourses within and outside of the academia. By entering into this critical debate, we develop a pragmatic and utilitarian theoretical framework on contemporary spatial publicness. In so doing, we highlight a neglected dimension in the existing studies of public space—social—to better elucidate how public spaces are used by their end-users

2. The Concepts of Publicness across Academic Fields

2.1. Patterns and Types of Publicness

The beginning of the concept of publicness in social science, such as politics and social studies, is considered to stem from the theory of the public sphere developed in modern times. Among them, in the field of politics, public sphere is understood as a place where power dynamic is revealed. Thus, misuse of power in the public sphere is considered as an obstacle to the realization of democracy. Gripsrud et al. [14] offers a comprehensive collection of key texts of publicness in public sphere theory from the Enlightenment era to the early 21st century. The leading scholars involved in the public sphere theory were Jürgen Habermas and Hannah Arendt.

Habermas [15] understands communication practice as a mutual understanding process of those who participate in Communication Action (Theori des kommunikativen Handelns) [15,16]. In addition to language-speaking, the process also includes omitted or implicit remarks [15]. Habermas [15] also describes that each communication action should be judged comprehensively by whether they are “propositional truth”, whether they are “subjective truthfulness” as the speaker says they are, and whether they are following “normative rightness”. Arendt [17] demonstrates human activity as labor, work, and action in The Human Condition. Of these, action is something similar to a human privilege, which is possible based on relationships and plurality between people, unlike labor and work [18,19]. Arendt argues that the private sphere is the area needed to fulfil biological needs and that the public is the area of freedom where “who” is revealed through words and actions [17,18,19].

Use of language-based public rationality, which is discussed in Kant’s concept of republicanism, is also in line with the concept of public sphere [20]. Pievatolo [21] explains that Kant sought an equal relationship with the order of the ruler and the approval of the citizen. He also said Kant advocated a public way of using reason publicly to stay away from authoritarianism and anarchism and maintain the republican state he claims exists [21]. Young [22] points out that discussions on communication, including Habermas’s theory, see participants as homogeneous social groups structurally discriminated by the domination and oppression of society, such as women, black people, sexual minorities, and people with disabilities. Young [22] also insisted that opinions of these structurally discriminated groups should be openly accepted for the just political community. This is also the way to achieve publicness through deliberative democracy [23].

Publicness as a conceptual tool underwent development in organizational theory and public policy studies [4,24,25]. Studies on publicness in organizational theory and public policy generally recognize the abstract definitions of publicness, embodying publicness in specific institutions and policy directions. They emphasize the juridico-political structure as a primary governing force of publicness. The first position views publicness as purely a legal existence through the initiatives of the nation-state. This position views the legitimacy of the public activities based on the constitution, the basic law of the state, as publicness. Since these activities deal with public affairs for the people, these activities have been considered aimed at increasing social publicness [26]. Second, publicness is considered as a process and procedural dimension. If publicness is most actively responsible for the communicative function of society, publicness is represented by the contents of the press, public interest profitability, democracy, and citizen-centered value, [27,28]. If the media, at its face value, is the locus of disseminating factual information, it is important that all citizens receive universal information on various social issues [29]. In this sense, publicness is realized when the process of contributing to social issues is explicitly implied and actualized. Im et al. [18] emphasize openness as a characteristic of information enabling consideration, discussion, and judgment on public issues.

In terms of the political process, Pesch [30] argues publicness is a generative process premised on debate and critical dialogues. Bozeman and Brestschneider [4] and Kaul [31] emphasize the communicative aspect of publicness, which highlights the various stakeholders’ positions for public projects reflected in the planning, decision making, and enforcement. Third, the meaning of publicness can be captured in the context of the resultant dimension. Moulton [32] conceptualizes publicness as embodying the public consensus, which she terms “realized publicness”. Lee [33] echoes this line of thought as the content of publicness needs to integrate and reflect social action. Kaul [31] highlights the benefit allocation, an aspect of publicness which considers how the resources of government, business, and civil society are distributed as a result. Ham [34] classifies sub-elements of publicness into (1) “publicness,” which should be able to solve problems that society wants to solve; (2) “sustainability,” where certain public services must be supplied continuously in a stable manner; (3) “fairness” in the sense that considerations should be given to those who are impoverished.

2.2. Reading Publicness in Light of the Spatial

When the term “publicness” is applied to a space or a place, existing analytic approaches operationalize various definitions of publicness in describing contemporary public spaces. The struggle against the contents of public space was one of the elements of the entire urbanist container. Since the quality of any place depends not only on its essential features, but also on the people who occupy it, the changes in the overall thinking of the social, economic and urban planning communities have had a significant impact on public space [1,3,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The term "public space", which has been disputed, has led to definitions that reflect various characteristics, including ownership [38], people’s behavior [42], accessibility [43] and democratic, responsive places [44]. The element of some degree of consensus in relation to public spaces is the concept that something has disappeared. Thus, in the past, seemingly shared and accessible public spaces have been replaced by more orderly places exposed to control, power, exclusion, and inaccessible narratives [38,45,46]. Uncertainty of diversity, urban spontaneity, and captivation of the urban flaneur have been replaced by expectations and knowledge of the urban environment. This is the cumulative result of a planning and governance structure that responds (or does not respond) to deeper structural changes occurring within society.

Most of the research focused on phenomena that occur in contemporary public places rather than on analyzing what characterizes disclosure itself. The recent discussions on spatial publicness can be largely divided into two distinctive categories: (1) contents of spatial characteristics; and (2) discursive spaces with a potential for political mobilization. Varna and Tiesdell [40] point out that there are two levels of publicness in space-conceptual and practical. The conceptual level focuses on the issue of equity, selection, and exclusion, depending on who uses and occupies the given space. It is the dominant definition of publicness in social science and humanities disciplines such as political science, geography, anthropology, and sociology. In contrast, the practical level emphasizes urban change as the main analytic focus. It is the dominant definition in conceptualizing publicness in practice-oriented fields such as architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning.

According to Carmona [1], the debates around the contemporary public space can be divided into two sides of interpretations. On one side, there are critics that focus on the concept of excessive control and management such as privatization and over-securitization [37,47,48,49,50,51]. Another consequence of this emphasis on space management is its commodification [38], leading to widespread criticism over the creation of idealistic spaces [52,53,54,55,56], characterized by an overall placeless-ness and a loss of authenticity [43,57]. In these new spaces, corporate cities are the epitome of the end of traditional public space amid a steady decline in public power [53], as political debates and the overall basic aspects of democracy are the first factors to disappear [49].

On the other hand, another side focuses on the visible effects of undermanagement, especially in terms of physical and social consequences. The development of the private realm or sector [58,59], the growth of the “third place” [60], and the spread of virtual space [45] have been triggers for new policies and development processes and have also been a factor in ending the social exclusion process [61,62,63,64,65]. These “cracks in the city” [49] are not, however, a recent phenomenon. In 1889, Sitte [66] discussed the deterioration of new public spaces and regretted the apparent loss of public life, at the height of the creation of a new public space in an industrial revolutionary era. Jane Jacobs [67] had also criticized this process in which new design theories originated uncivil behavior and consequently aggravated the concerns about crime, defending increased surveillance and territorial definition.

Physical and social depiction is one of the most discussed topics as the abandonment of public space increases. Privatization is seen as a way to boost and optimize this underused urban resource. It also relates to another area of discussion on the safety and security of public space [68]. As public life also exists in private spaces, good quality of design is one solution [69] for improving publicness [59,70]. Many authors have provided deep investigation about public city life; how to improve urban vitality; the role of the hybrid space (private open to the public); how to design public open spaces in light of “utilitarian aspects of urban and architectural space”. Jacobs [67] emphasized the importance of urban vitality and suggested desirable urban planning principles around “diversity” as a key attribute. She then criticized the planning and development activities that destroyed the diversity of the city. Whyte [65] and Gehl [71] also examined how outdoor space was used for people, revealing through their observations that what people are most interested in is the life and behavior they are leading with others, detailing how outdoor space is used for people. Discussing the impact of the design of public spaces on social interactions, Gehl [71] points out that there are several stages of transitional form in the middle, when isolated and together, and offers a range of contact strengths to choose from. Valued, this approach is in line with Jane Jacobs’ argument that without a horizontal, loose, selective shared life, separation due to hierarchical differences would lead to greater isolation and mere symbiosis.

3. Methods

3.1. Content Analysis

Content analysis is a well-established set of techniques for making inferences from text about sources, content, or receivers of information [72]. In order to analyze the trends of research in specific academic fields, the most commonly used method is content analysis of journals and articles in related fields that are issued regularly for a certain period of time [73,74]. Content analysis is a systematic and objective measurement of the contents, not through interviews or questionnaires, in the humanities, social sciences, and communication fields [75,76,77]. Using content analysis, development of coding scheme, and the reliability test are the most significant processes of research [78,79].

3.2. The Selection of News Article and Criteria

Using content analysis, we analyzed news articles on publicness reported in South Korea. The mass media, including newspapers, play an important role by reflecting the way the public perceives public issues, which in turn leads to an understanding of the population’s issues [80,81]. The unit of analysis is an individual news article. The major newspapers included in the analysis are ten major newspapers in South Korea, which includes Chosun Ilbo, Joongang Ilbo, Donga Ilbo, Hankook Ilbo, Kyunghyang Newspaper, Hankyoreh, Munhwa Ilbo, Kookmin Ilbo, and Seoul Newspaper. As mentioned above, in 2008, South Korea enacted the Framework Act on Construction which is the new law in a basic direction to promote the publicness of urban and architectural space. In this context, we selected articles on the media listed above from 1 January 2010, to 31 December 2018. We used the KINDS database (www.kinds.or.kr) provided by the Korea Press Foundation to collect the articles selected for analysis. Articles related to spatial publicness in Donga Ilbo, one of the top ten major newspapers not included in the KINDS database, were extracted by using the Donga Ilbo search service. We used random sampling to select articles that refer to the publicness in relation to architectural and urban spaces by titles and texts.

The search terms were “public”, “space”, “architecture”, and their derivatives. As a result, we retrieved a total of 1849 news articles. The exclusion criteria were articles not directly related to spaces and articles that overlapped with other articles. Finally, a total of 582 articles related to spatial publicness were included in the analysis. Table 1 shows the list of newspapers and the number of selected articles in each newspaper.

Table 1.

The number of selected articles in each newspaper.

3.3. Development of Coding Scheme (Coding Frame)

As a criterion for conducting content analysis, it is necessary to determine exactly how the classification system, coding sheet, is structured in accordance with the research questions [73,74]. To develop the coding sheet, categories were derived inductively from the texts being analyzed [82,83]. Inductive content analysis is particularly appropriate for research that takes a grounded theory approach, which derives theory from data rather than verifying existing theories [72]. To enhance intercoder reliability, we developed the coding scheme and classification types used in the full-scale coding process collectively. Overall, we developed three main coding schemes that broadly applied to the majority of the data: (1) conceptualization of contemporary spatial publicness in South Korea; (2) recognition of contemporary spatial publicness as a dominant cultural concept in South Korea; and (3) overall attitude towards spatial publicness (positive, neutral or ambivalent, negative).

We used the KrKwic.exe program primarily to find words that appeared frequently in 582 articles. We then selected 58 (10% of total) randomized articles to develop a coding scheme. Using an inductive way, the meaningful keywords that applied to the main topics of coding scheme were retrieved. To finalize the coding scheme, one of the researchers read all selected articles two or three times and coded them with open-ended coding. Two remaining researchers manipulated the coding scheme developed initially. Afterwards, all of the researchers attempted to complete the inductive category items through repeated discussions in order to maintain objective criteria for the final coding scheme.

3.4. Reliability Test

Content analysis as a method is prone to subjective judgment of the research team, and therefore prone to objective scholastic fallacy [78]. In order to avoid this subjective bias and to obtain the objective results, inter-coder reliability plays an important role in the validity of analysis results between the coders. We used the reliability coefficient method by Holsti [75] to verify the validity and reliability of intercoder reliability between the three researchers. In prior studies, the effective reliability coefficients of coders were 90% for Holsti [75] and 85% for Kassarjian [76].

To conduct a reliability analysis of this study, two graduate students were trained on how to code a particular topic with twenty news articles not included in this study. Afterwards, the newspapers collected by the research team were coded by the two trained coders in accordance with the final coding scheme developed by the research team. As a result, this study obtained a reliability coefficient of 86.3%, which is higher than that of Kassarjian [76].

3.5. Data Analysis

The data summarized by content analysis were coded as a nominal scale. Descriptive analysis was performed using statistical analysis software SPSS Ver.20.0. We used frequency and percentage distribution for our analysis.

4. Results

4.1. The Concept of Contemporary Spatial Publicness in South Korea

After analysis, we retrieved a total of 6 main categories and 58 subcategories related to spatial publicness based on our coding scheme. Among them, 26 terms referred to sites or subjects of spatial publicness while 27 categories referred to attributes of spatial publicness. Others in the main categories included words that framed spatial publicness as a main topic of importance. This category was divided into 5 sub-categories.

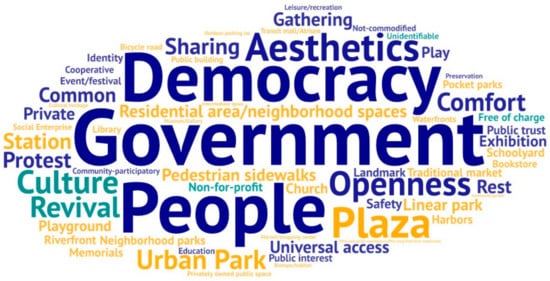

Table 2 shows the results for how spatial publicness is conceptualized in accordance with the coding scheme. This illustrates many similarities with the attribute of public space. Since many articles were related to introducing new projects initiated by institutions, “government” (475 times, 23.0%) was the most commonly cited keyword within the attribute category (Figure 1). “People” (368 times, 17.84%) was the second-most commonly cited word. The results of “business complex” (n = 21, 2.29%), “market/shopping center” (n = 12, 1.30%), “24 hours operation commerce/coffee shop/fast food restaurants” (n = 4, 0.43%), and “intermediate space” (n = 3, 0.32%) framed publicness in space as more related to accessibility than ownership. For example, “…[a]n example of public space is a large shopping center connecting the ground and the underground”[84]. As the influence of burgeoning of garden projects in South Korea, “pocket park” (n = 24, 2.61%), “outdoor parking lot” (n = 9, 0.98%), “community garden” (n = 3, 0.33%) framed public spaces as created by community-led efforts; “… [t]he well-kept gardens remained in the private space of rich people… But the experiment of pocket park is breaking this stereotype. The garden entered the city and began to turn into a public space with publicness” [85]. Profitability was framed in a manner that contrasted spatial publicness; “non-for-profit” (n = 32, 14.10%) and “free of charge” (n = 29, 12.78%), was closely related to publicness.

Table 2.

The concepts of contemporary spatial publicness in South Korea.

Figure 1.

Concepts of contemporary spatial publicness in South Korea.

From October 2016 to March 2017, South Korea witnessed the culmination of a political scandal leading up to the impeachment of the now former-president Geun-hye Park [86,87]. The political uproar that led to the mobilization of mass protests which took place in various public spaces in South Korea. During this time, mass protest against president Park was held around the main boulevards from the City Hall Plaza, Gwanghwamun Plaza, and Gyeongbok Palace on every Saturday. Articles that framed this context used words such the “plaza” (n = 128, 13.33%) with “democracy” (n = 231, 11.02%) such as "…[t]he space that enabled the direct democracy action of the sovereigns pouring into the streets…[88]”.

After the implementation of local self-governing system, each local government began to take an increasing interest in the construction of “cultural city” as a new developmental strategy. The strategy has been expanded since president Moo-hyun Roh’s administration (2002-2007) started to promote the project of “cultural city” to facilitate various local and regional development policies [89]. Since then, politicians often use the improvement of spatial publicness as a campaign pledge; “…[o]ne of the major promises of the new government…the new reorganization of the urban space must be based on publicness and the pursuit of urban regeneration in which the benefits are to all residents…[90].” Many local governments carried out projects similar to those of Seoul, the capital city of South Korea. Re-development of space as a way to improve publicness is widely recognized and accepted by the South Korean citizenry.

4.2. Recognition of Contemporary Spatial Publicness

Minimum search exclusion criteria were used to identify articles related to the architectural and urban spaces that contained the word “publicness”. Table 3 shows the various issues and contents as addressed by the articles.

Table 3.

Issues covered in news articles as a context of publicness.

“Projects regarding spatial publicness” was the most commonly appearing theme for articles published between 2010 and 2018 (381 articles, 65.46 %). The great majority of these articles focused on introductions, information, and resources over the new projects (311 articles). The topic that discussed ways to improve spatial publicness was the second-most popular theme (146 articles, 20.59%). Many articles on this subject (52 articles) criticized the environmental problems caused by the predominance of an economically-oriented planning, demanding the South Korean state and planners to consider issues of social inequality such as urban displacement and poverty. Other issues were broadly categorized as the factors that weaken spatial publicness (44 articles, 7.57%) and descriptions or opinions of phenomena relating to changes in perception of spatial publicness (11 articles, 1.89%).

4.3. Specific Concepts of Projects Regarding Contemporary Spatial Publicness

The specific concept of a project on spatial publicness is categorized according to who leads the project (Table 4). For projects that were led directly by the central government, there were many cases related to the residents’ environments such as “residential environment improvement project” (62 times) and “improvement of street environment” (29 times) (Figure 2). For example, “… [c]onsidering that there is a lack of publicness in the middle-class monthly rent apartment… the central government decided to strengthen publicness through rent cut and environment improvement”[91].

Table 4.

Specific concepts of projects regarding spatial publicness.

Figure 2.

Specific projects regarding spatial publicness.

In recent years, there has been a boisterous discussion regarding public design and design guidelines to improve urban landscape as well as regulation of outdoor advertisements that ruin urban aesthetics—this led to the various kinds of “public design project” (42 times). Public design project is also considered as an effective way of facilitating and visualizing spatial publicness; “our country is the republic and the core of the republic is the publicness. However, its publicness cannot be established without citizens. In some ways public design is the visualization of publicness on space of the republic”[92].

4.4. Specific Concepts of Methods for Facilitating Spatial Publicness

Contents discussed in the articles about ways to improve spatial publicness can be divided into five categories: (1) increasing the open space for the public; (2) preventing unsustainable developmental projects; (3) participation of residents and enhancing the roles of professionals; (4) improvement of publicness with public design; and (5) others (See details in Table 5). Among the categories in this theme, discussions of improving spatial publicness alluded to “government” most frequently (227, 111, 65, 72 and 22 times, respectively) (Figure 3). “Necessary” was the second-most commonly cited concept in relation to increasing open spaces for the public and publicness of the private space (164 times). The articles discussed mainly about the “government,” describing where the government conducted, or should conduct, “necessary” projects to enhance spatial publicness. For example, “…the government has a plan to create a place for people where publicness should be premised…”[93].

Table 5.

Specific concepts of methods for improving spatial publicness.

Figure 3.

Concepts of methods for improving spatial publicness.

Regardless of ownership, “building” (22 times) and “street environment” (68 times) have been considered as public spaces if there is a pledge for the space to accommodate towards all people; “it can be said that the building itself is an ’”open building”’ that acts as a street. This openness enhances the publicness of urban space…”[94].

The state is aware that in order to improve spatial publicness, the participation of local residents and the roles played by various professionals are central to enacting implemented policies:

…The government will introduce nationwide general and public architects who are professionally responsible for projects to improve publicness on public architecture…The General Architect System is a system that systematically and collectively manages public buildings by collecting opinions from local residents by putting architectural experts into the planning and design stages of public buildings and maintenance projects [95].

Additionally, some articles addressed how local governments have improved publicness in creating “cultural facilities” (22 times) that are easily accessible to local residents, such as galleries, libraries, and gyms, which are open to the public. Cultural facilities are crucial components of spatial publicness, which enhance the end-user experience of public spaces.

4.5. Factors that Weaken Contemporary Spatial Publicness

Concerning factors that weaken spatial publicness, “capital” (14 times), “power” (8 times), and “gentrification” (11 times) were addressed as factors of “neoliberal forces” (3 times) which raised concerns about “crime and safety” (3 times) (Table 6). For example, “how to turn a capital and power-dominated city into a public place (occupation)…”[96]. Gentrification is considered as a phenomenon somewhat related to the “resident-led” (16 times) process and “management” (6 times); “…If the residential environment management project is not led by the residents, and they agonize over publicness of the space without considering phenomenon of the gentrification, the problem of the management of the space eventually comes out…”[97].

Table 6.

Concepts of factors that weaken spatial publicness.

4.6. Transition of Awareness on Spatial Publicness

There were several rigorous opinions by professionals regarding the transition of awareness on spatial publicness (Table 7). They emphasize the necessity of more cultural spaces, and the community built enough participation of residents, which receives attention in the public sphere. Thus, it is necessary to move away from the administration-led type and enhance the “roles of various stakeholders” (4 times) and “resident-led” (4 times); “…citizens make cities and cities make citizens again, in the same context, participation of residents enhances publicness and promotes democratization of space…”[98].

Table 7.

Concepts of transition of awareness on spatial publicness.

4.7. Overall Attitude of Articles toward Facilitating Spatial Publicness

In the context of South Korea, the overall attitude (455 articles, 78.2%) towards institutional ways of facilitating spatial publicness is received in a positive manner. Spatial publicness has a normative dimension that is often understood reciprocally with the development of a place, especially in the sociopolitical and sociohistorical context of South Korea. Most of the articles with contents that represented neutral or ambivalent attitudes (134 articles, 22.6%) addressed spatial publicness as a way of introducing policies or institutions; only 3 articles had negative attitudes toward spatial publicness. It is important to note that all of the articles cited the problems related to gentrification.

5. New Characteristics of Contemporary Spatial Publicness

Various statutes or actions were related to the realization of contemporary spatial publicness across context. In most articles, the core concept surrounding spatial publicness was "government," which is considered as the main provider of public space, as well as the owner of them from the past. Overall, the concept of contemporary spatial publicness in the South Korean discourse can be summarized as the following: (1) a legitimated act by public institutions such as the state or the government, which presupposes national interests; (2) a common and universal perception of a large number of people (i.e., democracy) with the premise of public interests; (3) a measure of the value of a place with accessibility that provides general visibility to all people. Reflecting our results, in a broader context, traditional definition of spatial publicness, which defines the concept of traditional outdoor space for public ownership, seems to be valid to some extent in modern times. The result of highly rated keywords like “Government”, “People”, “Democracy”, and “Necessary,” implies that the concept of “spatial” publicness, on the other hand, overlaps with its meaning in social-science academic fields.

Drawing a line between “continuous” and “new” characteristics of contemporary spatial publicness is abstruse. To distinguish, in what follows, we delineate the predominant positions on new characteristics of contemporary spatial publicness. The new characteristics of contemporary spatial publicness are derived from three distinct types of conditions: (1) prerequisite conditions; (2) subjective conditions; and (3) practical conditions (See details in Table 8).

Table 8.

New characteristics of contemporary spatial publicness.

Within this typology, five concepts have been specified as new characteristics of contemporary spatial publicness.

First, the mainstream of social discourse is receptive to the blurring of the boundary between private and public spaces. In South Korea, there have been active discussions on securing the spatial publicness by publicizing private spaces through the Opening of Fences Movement at public buildings or universities since the 2000s. The Opening of Fences Movement plays a significant role in fostering community cultures through diverse meetings and sharing between neighbors. Public buildings have recently been improved as cultural spaces by accommodating facilities that are readily available to local residents, such as galleries, wedding halls, local specialty product stores, reading rooms and fitness centers. Organizations in the private sector are also seeking ways to improve spatial publicness in order to increase accessibility and maximize spatial occupancy—doing so is a pragmatic fiscal decision to maximize consumption processes [13]. As such, contemporary spatial publicness should be recognized as a continuum and relativities of space [1,3,39,51,54,99,100].

Second, in the process of implementing spatial publicness, the administration role has shifted to supporting rather than leading. This shift characterizes the antiquated administrative protocols in the past to the current paradigm. Establishments of cooperative relations among the stakeholders are of utmost significance. In this context, the role of architects and planners is crucial to promote local publicness [13]. In addition, various ways of activating and invigorating spatial publicness of the local area should be extended to the role of their community. Doing so is crucial to fostering strategies that promote spatial publicness at the local level.

Third, the value sharing and consensus process among stakeholders increases the probability of making a public place truly “open and accessible.” To this end, the importance of a shared processes—a collective consciousness [101]—dissolves conflict through rational communication such as dialogue, argument essential to the public discourse (i.e., democracy) [15]. An emphasis is needed to allocate sufficient time in order to ensure the possibility of voluntary participation and consensus of the public, which is at the heart of the democratic process.

Fourth, we must recognize the importance of management and operations in relation to the diversification of its constituents. There has been a steady stream of research that highlights the need for a shift in perception toward managing and operating a space beyond the result-oriented perspective [3]. It is also necessary to establish a trust relationship between the relevant parties. This is crucial to the management and operation of the space in order to establish a continuous communication venue.

The fifth is the recognition and awareness of reckless development and respecting the historical context of regions and places, which promotes spatial publicness. This can be seen as an extension of the fact that the aspect of amenity has always appeared as an evaluation index on publicness of public spaces [40,102,103,104]. Projects related to public design, focusing not only on the quality of design but also on locality and sense of place, were carried out to promote spatial publicness. Various academic fields of architecture, art, design and landscape related to architectural urban space play an important role in establishing relationships aimed at creating a collective identity.

6. Conclusions

The concept of spatial publicness has been more comprehensively explored as a shift of responsibility from the public to the private sector in various spheres of society [30,105,106]. Spatial publicness is a useful concept that better captures the complexities of spaces accessible to the public because it goes beyond this binary distinction. It can also be varied depending on contextual factors such as time and environment. Various disciplinary fields utilize the term publicness, albeit not in a unified definition as operationalized in this study. Many studies have already contributed to public urban life, including ways to improve urban vitality and the role of “liminal spaces” [56]. Utilizing publicness in a single register of meaning has the potential to reduce its multidimensional nature but also allows for a unified explanation by isolating a particularly relevant aspect to publicness in a given space. In this way, utilizing publicness opens up potential to clearly conceptualize public space over the various obscure definitions that limits practical applicability.

We used a content analysis of news articles, which is a useful tool for measuring public awareness, apart from the vague and ambiguous definitions that permeate various academic tendencies and urban policies and plans. In 2008, South Korea newly enacted the Framework Act on Construction as a new law, which emphasized the spatial publicness in its institutional aspect while realizing architectural space, social and cultural public character as the basic direction of architectural policy. Doing so, they consciously considered the social, cultural, political, and historical aspects of Korean architecture and planning. Contemporary spatial publicness is a strong conceptual tool that contextualizes the contemporary backdrop of environmental degradation caused by reckless development projects in Korea.

Our results show that the traditional methods of defining public and private spaces are still valid in some respects and have difficulty distinguishing new characteristics of spatial publicness compared to the past. However, considering that spatial publicness is revealed through the whole process of creating a place, new features of contemporary spatial publicness can be delineated. Especially, enhancing participation and roles of various stakeholders is an important facilitating factor of contemporary spatial publicness. This study also highlights the social value of public consensus in relation to contemporary spatial publicness. A new approach is needed to assess the publicness of architectural and urban spaces by indicators of diversity, communication, cooperative relationships, and consensus processes of participants, based on procedures of making place.

There are two main suggestions for practical adaptations. First, a more in-depth theoretical study should be carried out around the humanities literature review to complement the theoretical completeness of establishing the concept of contemporary spatial publicness. The second is that further researches should be followed to ensure that the practical way for facilitating spatial publicness are more specific. With tendencies of burgeoning NGOs and various partnerships as new public entities and of changes in the public role of the administration from initiative to support, a systematic analysis of the desired roles that the relevant entities should play is necessary for encouraging the participation of the various entities. Consideration needs to be given to devising institutional measures to promote the role of administration in partnership and support. In addition, in order to share a common learning process for value sharing and social consensus processes and to ensure a sufficient planning period, a process is needed to demand consensus processes among the stakeholders. This requires a review of the design of the planning process and a review of the methodology for communication tools and support systems that support joint learning. Moreover, it is necessary to switch to the public monopoly by administration and to establish a communication structure between the relevant parties. To this end, a detailed review of the management system for division of roles between administration and the private sector is required. Establishing a collaborative-communication relationship between different stakeholders should be considered in terms of governance.

Our conceptual framework emphasizes the utilitarian and functional aspects of contemporary spatial publicness, which opens democratic possibilities, such as movement mobilization through public consensus. The results confirm the existing theoretical frameworks while building a more nuanced definition through operationalizing contemporary spatial publicness in relation to urban and architectural space. Hence, further researches can be taken in two directions. First, in-depth theoretical studies in the field of humanities and sociology should be conducted to complement the theoretical concept of contemporary spatial publicness. Researches are also needed to further refine the items presented to enhance the spatial publicness and ensure their practicality.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to the intellectual content of this paper. The first author, S.H., developed the flow of this study and contributed to interpretation of all results and discussion. J.W.K. contributed to the discussion part and wrote the manuscript. Y.K. substantially contributed to the research design and developed the result part.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carmona, M. Contemporary public space: Critique and classification, part one: Critique. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aernouts, N.; Ryckewaert, M. Reconceptualizing the “Publicness” of Public Housing: The Case of Brussels. Soc. Incl. 2015, 3, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkar, M. The changing ‘publicness’ of contemporary public spaces: A case study of the Grey’s Monument Area, Newcastle upon Tyne. Urban Des. Int. 2005, 10, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, B.; Bretschneider, S. The “publicness puzzle” in organization theory: A test of alternative explanations of differences between public and private organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1994, 4, 197–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mantey, D. The ‘publicness’ of suburban gathering places: The example of Podkowa Leśna (Warsaw urban region, Poland). Cities 2017, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, U.Y. The typification of publicness. Korean Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 44, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gaus, G.F.; Benn, S.I. Public and Private in Social Life; Croom Helm: London, UK; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0-7099-0668-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, J.M. A Study on Publicness Perception Types using Q Methodology. Korean Soc. Public Adm. 2018, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Everyday Life in the Modern World; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheringham, M. Everyday Life: Theories and Practices from Surrealism to the Present; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. Investigation into Shanghai Spatial Publicness. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Youm, C.H.; Cho, J.; Sim, K.M. A Fundamental Study on the Contemporary Publicness of Architecture & Urban Space; AURIC Publication: Rambouillet, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H.; Benhabib, S.; Bohman, J.; Dewey, J.; Elster, J.; Fraser, N.; Habermas, J.; Hegel, G.F.; Kant, I.; Kluge, A.; et al. The Idea of the Public Sphere: A Reader; Gripsrud, J., Hallvard, M., Anders, M., Graham, M., Eds.; Lexington Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, T. Kantian constructivism and reconstructivism: Rawls and Habermas in dialogue. Ethics 1994, 105, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, H. The Human Condition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Im, E.Y.; Ko, H.G.; Park, J.H. Hannah Arendt‘s Public Sphere and Public Administration. J. Gov. Stud. 2014, 20, 71–101. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, S. Hannah Arendt and the Challenge of Modernity: A Phenomenology of Human Rights; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Raventós, D.; Casassas, D. Republicanism and Basic Income: The articulation of the public sphere from the repoliticization of the private sphere. In Proceedings of the Nineth International Congress of the Basic Income Guarantee Network, Geneva, Switzerland, 12–14 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pievatolo, M.C. Publicness and private intellectual property in Kant’s political thought 2008. In Proceedings of the 10th International Kant Congress, São Paulo, Brasil, 4–9 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Inclusion and Democracy; Oxford University Press on Demand: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Husband, C. The right to be understood: Conceiving the multi-ethnic public sphere. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 1996, 9, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozeman, B. All Organizations Are Public: Comparing Public and Private Organizations; Beard Books: State College, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeman, B. What organization theorists and public policy researchers can learn from one another: Publicness theory as a case-in-point. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.G. Publicness as legal justification of administration. J. Inst. Stud. Law Dong Univ. 2012, 5, 47–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, B.; Rosenstiel, T. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect; Three Rivers Press (CA): New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y.; Park, S.H. The Diachronic Change of Election Report in the Coverage of the Korean Presidential Election since 1992. Stud. Broadcast. C. 2014, 26, 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, J. Publicness; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pesch, U. The publicness of public administration. Adm. Soc. 2008, 40, 170–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, I. Private provision and global public goods: Do the two go together? Glob. Soc. Policy 2005, 5, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, S. Putting together the publicness puzzle: A framework for realized publicness. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.R. Cultural Policy and Publicness. Korean Assoc. Gov. 2011, 18, 119–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, Y.S. The Study of Factors and Publicness on Customer Satisfaction of the Public Service: Focus on the Subway Service in Seoul. Korean Assoc. Local Gov. Stud. 2011, 23, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, T. The future of public space: Beyond invented streets and reinvented places. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2001, 67, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Contemporary public space, part two: Classification. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveson, K. Publics and the City; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 80. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, M. Brave New Neighborhoods: The Privatization of Public Space; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ne’meth, J.; Schmidt, S. The privatization of public space: Modeling and measuring publicness. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2011, 38, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varna, G.; Tiesdell, S. Assessing the Publicness of Public Space:The Star Model of Publicness. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. City life and difference. In People Place and Space Reader; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 1990; pp. 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J.; Gemzøe, L. New City Spaces; Danish National Research Datebase: Copenhagen, Danish, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places-Urban Spaces; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Stone, A.M. Public Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. Introduction: Public space and the city. Urban Geogr. 1996, 17, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. Domestication by cappuccino or a revenge on urban space? Control and empowerment in the management of public spaces. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1829–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, N.R.; Bannister, J. The eyes upon the street. In Images Street Plan. Identity Control Public Space; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Banerjee, T. Urban Design Downtown: Poetics and Politics of Form; Univ of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.; Smith, N. The Politics of Public Space; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Public and Private Spaces of the City; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sircus, J. Invented Places’, in Carmona M and Tiesdell S (eds.) Urban Design Reader, Amsterdam (etc.) Architectural Press; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, M. See you in Disneyland. In Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space; Western Designers: Tokyo, Japan, 1992; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Van Melik, R.; Van Aalst, I.; Van Weesep, J. Fear and fantasy in the public domain: The development of secured and themed urban space. J. Urban Des. 2007, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Melik, R.; Van Aalst, I.; Van Weesep, J. The private sector and public space in Dutch city centres. Cities 2009, 26, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. The Cultures of Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellin, N. Postmodern Urbanism; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The Fall of Public Man; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Da Capo Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. Control as a dimension of public-space quality. In Public Places and Spaces; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1989; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, L.H. Social life in the public realm: A review. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 1989, 17, 453–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. City centre management and safer city centres: Approaches in Coventry and Nottingham. Cities 1998, 15, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, R. Gender, race, age and fear in the city. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; UC Berkeley Transportation Library: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sitte, C. City Building According to Artistic Principles; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1889. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; De Magalhaes, C. Public space management: Present and potential. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2006, 49, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbalds, F. Making People-Friendly Towns: Improving the Public Environment in Towns and Cities; Taylor & Francis: Milton Park, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World; Univ of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schamber, L. Time-line interviews and inductive content analysis: Their effectiveness for exploring cognitive behaviors. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 2000, 51, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.; Jung, W.; Kim, Y. Research trends regarding foodservice management: Review of Journal of Foodservice Management Society of Korea. J. Foodserv. Manag. 2007, 10, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, I. Content analysis: Applications to tourism research. J. Tour. Sci. 2000, 24, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O. Content analysis. In The Handbook of Social Psychology; Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content analysis in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications: Saunders Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Kim, Y. The impacts on foodservice quality through a content analysis: The differences of perceptions between consumers and scholars. J. Foodserv. Manag. 2008, 11, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Cho, M. Content analysis of the New York Times on Korean restaurants from 1980 to 2005. J. Foodserv. Manag. 2008, 11, 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M.; Ross, I.E.; Gasher, M.; Gutstein, D.; Dunn, J.R.; Hackett, R.A. Telling stories: News media, health literacy and public policy in Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, C. Health and media: An overview. Soc. Health Illn. 2003, 25, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B. Content Analysis. A Method in Social Science Research; Raswat Publications: Rajasthan, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative analysis of content. Appl. Soc. Res. Methods Quest. Inf. Library Sci. 2009, 308, 319. [Google Scholar]

- Pae, Y.S. Asking the representative of Zaha Hadid Architectural Office and the two young Korean architects “The Way of Architecture” 자하 하디드 건축사무소 대표와 한국의 두 젊은 건축가에게 ’건축의 길’을 묻다. Joongang Ilbo, 2017. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/21941564(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Im, J.U. Garden Goes to City 도시로 간 정원, 잿빛 공터에 풀빛 물들이다. Hankyoreh, 2013. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/culture_general/607528.html(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Doucette, J. The Occult of Personality: Korea’s Candlelight Protests and the Impeachment of Park Geun-hye. J. Asian Stud. 2017, 76, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.-W.; Moon, R.J. South Korea after impeachment. J. Democr. 2017, 28, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShinYoon, D.W. ‘Passion Theater’ embracing the Plaza 블랙리스트들이 만든 광화문광장의 ‘블랙텐트’에 넘치는 열정과 해방의 쾌감. Hankyoreh, 2017. Available online: http://h21.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/43097.html(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Lee, J.-H.; Yun, S.-J. A comparative study of governance in state management: Focusing on the Roh Moo-hyun government and the Lee Myung-bak government. Dev. Soc. 2011, 40, 289–318. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, S.C. Busan Regional Innovation Movement Headquarters, Hold Forum for 2018 Local Autonomy Election 부산분권혁신운동본부, ‘2018 지방선거’ 포럼 개최. Joongang Ilbo, 2017. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/22178248(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Lee, S.H. Ministry of Land erased the name of Newstay, symbol of Park Geun-hye and publicness is greatly strengthened 국토부 박근혜식 ‘뉴스테이’ 명칭 지웠다···공공성은 대폭 강화. Kyunghyang Newspaper, 2017. Available online: http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?art_id=201709151119001(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Choi, B. The public design that’s alienated from the citizens 시민과 동떨어진 공공디자인은…이렇게 조용히 잊혀진다. Kyunghyang Newspaper, 2018. Available online: http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?art_id=201801032148005(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Kim, S.H. Jamsil Sports Complex, changed to MICE base 잠실운동장 일대 국제 비즈니스센터로. Chosun Ilbo, 2016. Available online: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2016/04/26/2016042600102.html(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Oh, M.H. Rotterdam, the leader of a state-of-the-art modern architecture experiment 최첨단 현대건축 실험의 장, 로테르담. Hankook Ilbo, 2010. Available online: https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201008181243242718(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Jeon, S.P. The Government is planning for the introduction of the General Architect System nationwide 정부, 총괄건축가 제도 전국 도입 추진. Chosun Ilbo, 2018. Available online: http://biz.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/10/04/2018100401859.html(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Back, S.C. The city dominated by capital and power, and the hidden conceit 자본·권력이 지배하는 도시, 감춰진 속내를 들추다. Kyunghyang Newspaper, 2014. Available online: http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?art_id=201410142154315(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Kim, B. A resident leaves a village built by a resident… an enemy of village making… gentrification 주민이 만든 마을에서 주민이떠난다…마을만들기의 적(敵) ‘젠트리피케이션’. Kyunghyang Newspaper, 2015. Available online: http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?art_id=201504241943161(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Kim, Y.N. Mayor Park Won-soon won the World Urban Award for Lee Kuan Yew: “The Great Citizens have made a great city-renewal triumph.” 박원순 시장, 리콴유 세계도시상 수상 “위대한 시민이 도시재생 쾌거 일궜다”. Kookmin Ilbo, 2018. Available online: http://news.kmib.co.kr/article/view.asp?arcid=0923977818(accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Németh, J. Defining a Public: The Management of Privately Owned Public Space. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 2463–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varna, G. Measuring Public Space: The Star Model; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life [1912]; NA: Van Nuys, CA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Space Syntax: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Cities as movement economies. Urban Des. Int. 1996, 1, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, S.; Crucitti, P.; Latora, V. Multiple centrality assessment in Parma: A network analysis of paths and open spaces. Urban Des. Int. 2008, 13, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U. The Predicaments of Publicness: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Ambiguity of Public Administration; Eburon Uitgeverij BV: Vredenburg, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Q. The Ludic City: Exploring the Potential of Public Spaces; Routledge: Abington, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).