Contextual Factors and Organizational Commitment: Examining the Mediating Role of Thriving at Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

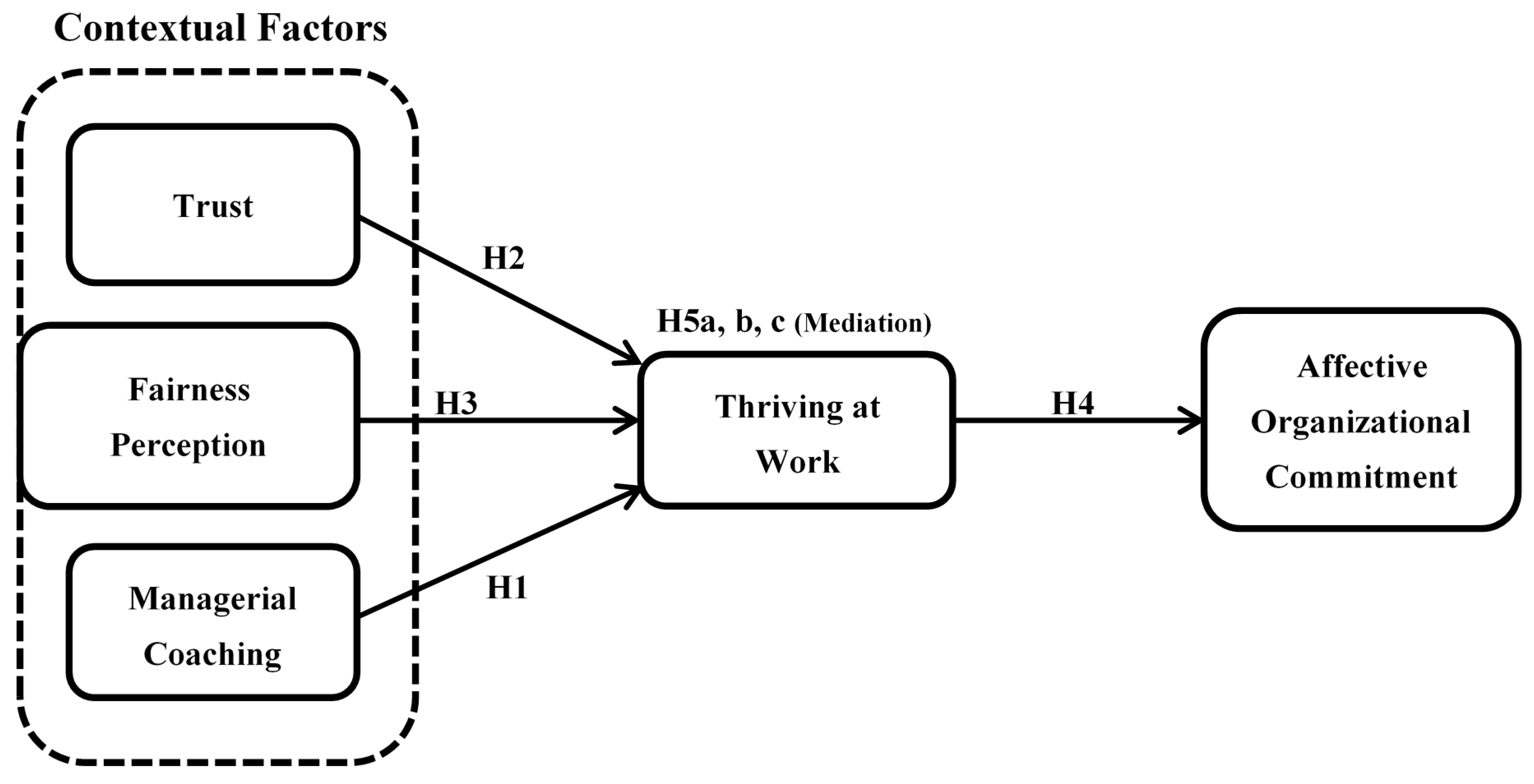

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Managerial Coaching

2.2. Trust and Fairness Perception

2.3. Thriving at Work and Commitment

2.4. Thriving at Work as a Mediator

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Managerial Coaching

3.2.2. Fairness Perception

3.2.3. Thriving at Work

3.2.4. Affective Organizational Commitment

3.2.5. Trust

3.2.6. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Internal Consistency

4.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

4.3. Multicollinearity Statistics

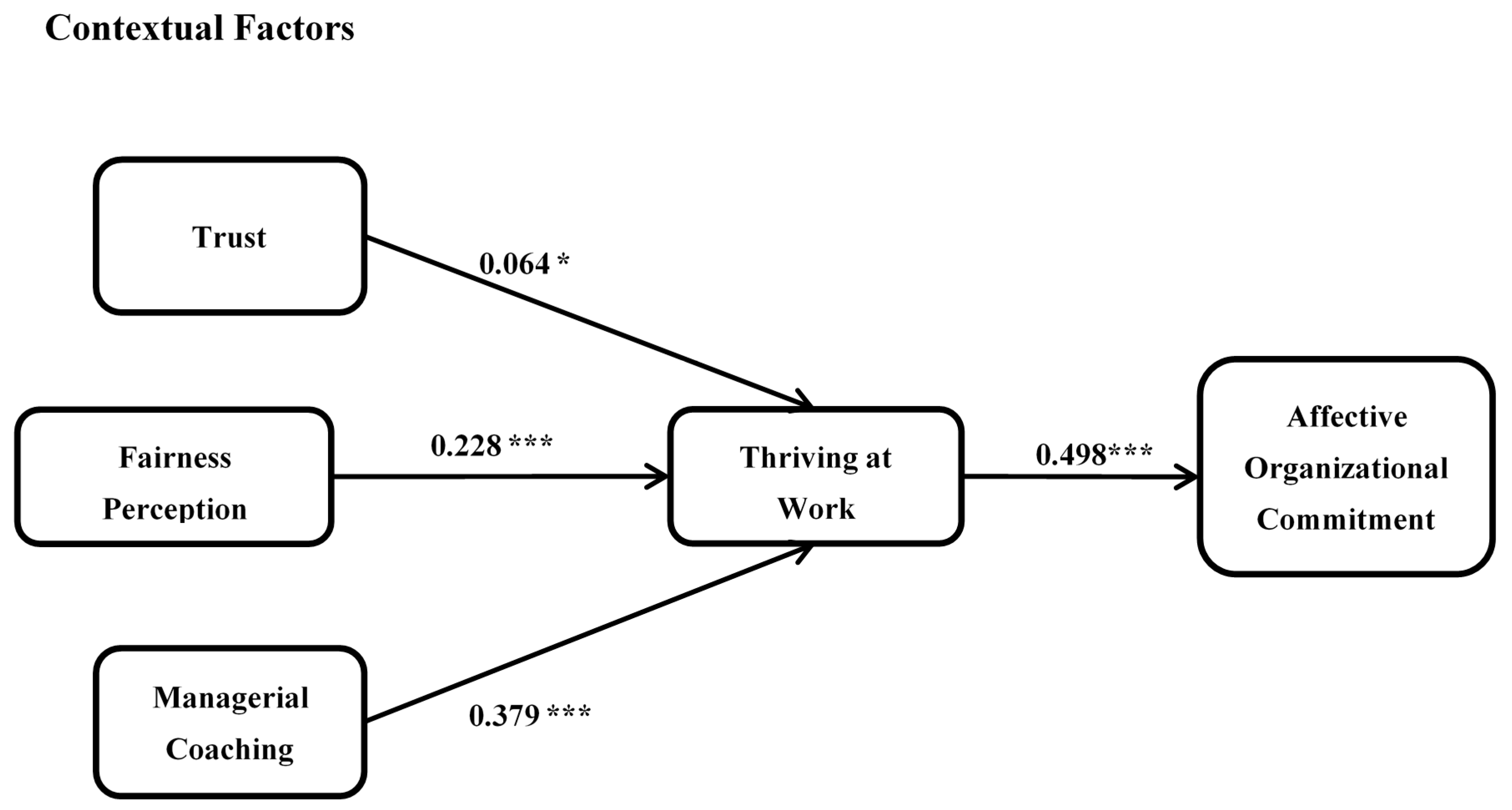

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paterson, T.A.; Luthans, F.; Jeung, W. Thriving at work: Impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J. Org. Beh. 2014, 35, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A Socially Embedded Model of Thriving at Work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Porath, C.L.; Gibson, C.B. Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Org. Dyn. 2012, 41, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Porath, C. Creating sustainable performance. Harv. B Rev. 2012, 90, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Arya, B.; Farooqi, S. Workplace behavioral antecedents of job performance: Mediating role of thriving. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Abid, G.; Arya, B.; Bhatti, G.A.; Farooqi, S. Understanding employee thriving: The role of workplace context, personality and individual resources. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2018, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Sustainable Work over the Life Course: Concept Paper; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Building Sustainable Organizations: The Human Factor. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, J.C.; Butts, M.M.; Johnson, P.D.; Stevens, F.G.; Smith, M.B. A multilevel model of employee innovation understanding the effects of regulatory focus, thriving, and employee involvement climate. J. Man. 2016, 42, 982–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Muchiri, M.K.; Misati, E.; Wu, C.; Meiliani, M. Inspired to perform: A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of thriving at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 39, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Peeters, M.C. The Vital Worker: Towards Sustainable Performance at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scheppingen, A.R.; De Vroome, E.M.; Have, K.C.; Zwetsloot, G.I.; Wiezer, N.; Van Mechelen, W. Vitality at work and its associations with lifestyle, self-determination, organizational culture, and with employees’ performance and sustainable employability. Work 2015, 52, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abid, G.; Zahra, I.; Ahmed, A. Mediated mechanism of thriving at work between perceived organization support, innovative work behavior and turnover intention. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2015, 9, 982–998. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, G.; Zahra, I.; Ahmed, A. Promoting thriving at work and waning turnover intention: A relational perspective. Future Bus. J. 2016, 2, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G. How does thriving matter at workplace. Int. J. Econ. Empir. Res. 2016, 4, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, M.L.; Tupper, C. Supervisor Prosocial Motivation, Employee Thriving, and Helping Behavior: A Trickle-Down Model of Psychological Safety. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 43, 561–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S. Thriving at workplace: Contributing to self-development, career development, and better performance in information organizations. Pak. J. Inf. Man. Lib. 2016, 17, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Spreitzer, G.M. Trust, Connectivity, and Thriving: Implications for Innovative Behaviors at Work. J. Creat. Behav. 2009, 43, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Sajjad, I.; Elahi, N.S.; Farooqi, S.; Nisar, A. The influence of prosocial motivation and civility on work engagement: The mediating role of thriving at work. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, R.A. Positive Psychology at Work: Psychological Capital and Thriving as Pathways to Employee Engagement. Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Flinchbaugh, C.; Luth, M.T.; Li, P. A Challenge or a Hindrance? Understanding the Effects of Stressors and Thriving on Life Satisfaction. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2015, 22, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Proactive personality and career adaptability: The role of thriving at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaiser, S.; Abid, G.; Arya, B.; Farooqi, S. Nourishing the bliss: Antecedents and mechanism of happiness at work. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2018, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C.; Sonnentag, S.; Sach, F. Thriving at work—A diary study. J. Org. Beh. 2012, 33, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; McLean, G.N.; Yang, B. Revision and validation of an instrument measuring managerial coaching skills in organizations. In Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development International Research Conference in the Americas, Panama City, FL, USA, 20–24 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppel, C.P.; Harrington, S.J. The Relationship of Communication, Ethical Work Climate, and Trust to Commitment and Innovation. J. Bus. Ethic 2000, 25, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M.S. Managerial coaching: A review of the literature. Perform. Improv. Q. 2012, 24, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, R.S.; Kim, S.; Hagen, M.S.; Egan, T.M.; Ellinger, A.D.; Hamlin, R.G. Managerial coaching: A review of the empirical literature and development of a model to guide future practice. Adv. Dev. Hum. Res. 2014, 16, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampa-Kokesch, S.; Anderson, M.Z. Executive coaching: A comprehensive review of the literature. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2001, 53, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, M.L.; Schminke, M. The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard-Oettel, C.; De Cuyper, N.; Schreurs, B.; De Witte, H. Linking job insecurity to well-being and organizational attitudes in Belgian workers: The role of security expectations and fairness. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1866–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, M.S.; Lee, C.B.; Joo, J.J. Organizational justice and organizational commitment among South Korean police officers: An investigation of job satisfaction as a mediator. Policing Int. J. 2012, 35, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.M.L. Distributive Justice, Procedural Justice, Affective Commitment, and Turnover Intention: A Mediation-Moderation Framework1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1505–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.L.; Lau, C.M. The impact of performance measures on employee fairness perceptions, job satisfaction and organisational commitment. J. Appl. Manag. Acc. Res. 2012, 10, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, A.D.; Ellinger, A.E.; Bachrach, D.G.; Wang, Y.L.; Elmadağ Baş, A.B. Organizational investments in social capital, managerial coaching, and employee work-related performance. Manag. Lear. 2011, 42, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, A.D. Supportive supervisors and managerial coaching: Exploring their managerial coaching on organizational commitment. Sustainability 2013, 9, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Har, C.L. Investigating the Impact of Managerial Coaching on Employees’ Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention in Malaysia. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Maiaysia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. Relationships among Managerial Coaching in Organizations and the Outcomes of Personal Learning, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intention; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, H.R. Exploratory Study Examining the Joint Impacts of Mentoring and Managerial Coaching on Organizational Commitment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, G.; Milner, J. Managerial coaching: Challenges, opportunities and training. J. Manag. Dev. 2013, 32, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theeboom, T.; Beersma, B.; van Vianen, A.E. Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, A.D.; Ellinger, A.E.; Keller, S.B. Supervisory coaching behavior, employee satisfaction, and warehouse employee performance: A dyadic perspective in the distribution industry. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2003, 14, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Egan, T.M.; Moon, M.J. Managerial coaching efficacy, work-related attitudes, and performance in public organizations: A comparative international study. Rev. Pub. Pers. Adm. 2014, 34, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue-Chan, C.; Wood, R.E.; Latham, G.P. Effect of a coach’s regulatory focus and an individual’s implicit person theory on individual performance. J. Man. 2012, 38, 809–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.J. The Effects of Managerial Coaching on Work Performance: The Mediating Roles of Role Clarity and Psychological Empowerment. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Batt, R. How supervisors influence performance: A multilevel study of coaching and group management in technology-mediated services. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 265–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousa, C.; Mathieu, A. Is managerial coaching a source of competitive advantage? Promoting employee self-regulation through coaching. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Egan, T.M.; Kim, W.; Kim, J. The Impact of Managerial Coaching Behavior on Employee Work-Related Reactions. J. Bus. Psychol. 2013, 28, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Assessing the Influence of Managerial Coaching on Employee Outcomes. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2014, 25, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.L.; Beimers, D. “Put me in, Coach”: A pilot evaluation of executive coaching in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2009, 19, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, A.D.; Bostrom, R.P. Managerial coaching behaviors in learning organizations. J. Manag. Dev. 1999, 18, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M.; Aguilar, M.G. The impact of managerial coaching on learning outcomes within the team context: An analysis. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2012, 23, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Curtayne, L.; Burton, G. Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: A randomised controlled study. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, H.K.; Liu, J.; Yim, F.H.K. Effects of mentoring functions on receivers’ organizational citizenship behavior in a Chinese context: A two-study investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, A.D.; Ellinger, A.E.; Keller, S.B. Supervisory Coaching Behavior: Is there a Pay off? In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Academy of Human Resource Development, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 27 February–3 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, B.S.; Kozlowski, S.W. Active learning: Effects of core training design elements on self-regulatory processes, learning, and adaptability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Khan, B.; Hong, M.C.-W. Thriving at Work: How Fairness Perception Matters for Employee’s Thriving and Job Satisfaction. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2016, 2016, 11948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Thriving in Organizations; Nelson, D.L., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Positive Organizational Behavior: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, M.; Abid, G.; Sarwar, K.; Ahmed, S. Forging ahead: How to thrive at the modern workplace. Iran. J. Man. Stud. 2017, 10, 783–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Tyler, T.R. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, S.S.; Lewis, K.; Goldman, B.M.; Taylor, M.S. Integrating Justice and Social Exchange: The Differing Effects of Fair Procedures and Treatment on Work Relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 738–748. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Truxillo, D.M.; Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Hammer, L. Perceptions of overall fairness: Are effects on job performance moderated by leader-member exchange? Hum. Perform. 2000, 22, 432–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Y.; Chang, P.L.; Yeh, C.W.; Chen, T.; Chang, P.; Yeh, C. A study of career needs, career development programs, job satisfaction and the turnover intentions of R&D personnel. Career Dev. Int. 2004, 9, 424–437. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Bern-Klug, M. Nursing Home Social Services Directors Who Report Thriving at Work. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2013, 56, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organization Linkages; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Aubé, C.; Rousseau, V.; Morin, E.M. Perceived organizational support and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of locus of control and work autonomy. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Zhu, W.; Koh, W.; Bhatia, P. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, S.; Qun, W.; Hui, L.; Shafi, A. Influence of Social Exchange Relationships on Affective Commitment and Innovative Behavior: Role of Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Butts, M.M.; Vandenberg, R.J.; DeJoy, D.M.; Wilson, M.G. Effects of management communication, opportunity for learning, and work schedule flexibility on organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S. Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.; Jacobs, R.L. Influences of formal learning, personal learning orientation, and supportive learning environment on informal learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.K.; Jo, S.J. Knowledge Sharing: The Influences of Learning Organization Culture, Organizational Commitment, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Solinger, O.N.; Van Olffen, W.; Roe, R.A. Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, Z.A. Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Hum. Res. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; Fonseca, M.A.; Ryan, M.K.; Rink, F.A.; Stoker, J.I.; Pieterse, A.N. How feedback about leadership potential impacts ambition, affective organizational commitment, and performance. Lead. Quar. 2018, 29, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedaner, F.; Kuntz, L.; Enke, C.; Roth, B.; Nitzsche, A. Exploring the differential impact of individual and organizational factors on affective organizational commitment of physicians and nurses. BMC Health Ser. Res. 2018, 18, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Luk, S.T.K.; Cardinali, S. The role of pre-consumption experience in perceived value of retailer brands: Consumers’ experience from emerging markets. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Process: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Kisbu-Sakarya, Y.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Miočević, M. The Distribution of the Product Explains Normal Theory Mediation Confidence Interval Estimation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2014, 49, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. Lisrel 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the Simplis Command Language; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. Regression Diagnostics; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.T.; Hsieh, H.H. Supervisors as good coaches: Influences of coaching on employees’ in-role behaviors and proactive career behaviors. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2015, 26, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, K.E.; Ragins, B.R. The Landscape of Mentoring in the 21st Century. The Handbook of Mentoring at Work: Theory, Research, and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 659–692. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, R.C. Increasing affective organizational commitment in public organizations: The key role of interpersonal trust. Rev. Pub. Pers. Adm. 1999, 19, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R.; Konovsky, M.A. Effects of Procedural and Distributive Justice on Reactions to Pay Raise Decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

| Models | χ2 | Df | χ2/df | GFI | NFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Factor (Full Measurement Model) | 1142.55 | 325 | 3.52 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| 4 Factor Model a | 2805.69 | 344 | 8.16 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| 4 Factor Model b | 2980.88 | 344 | 8.67 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| 3 Factor Model c | 3402.98 | 347 | 9.81 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| 2 Factor Model d | 4348.97 | 349 | 12.46 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| 1 Factor Model e | 5011.37 | 350 | 14.32 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 29.68 | 7.24 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Gender | −0.214 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Marital Status | 0.592 ** | −0.161 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. Education | 15.67 | 1.507 | 0.118 ** | 0.065 * | 0.082 * | 1 | |||||

| 5. Tenure | 5.066 | 5.177 | 0.739 ** | −0.153 ** | 0.428 ** | −0.046 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Affective Organizational Commitment | 4.133 | 0.679 | 0.018 | −0.008 | 0.005 | 0.063 | 0.014 | 1 | |||

| 7. Thriving at Work | 4.117 | 0.547 | −0.047 | −0.030 | −0.019 | −0.015 | −0.094 ** | 0.483 ** | 1 | ||

| 8. Fairness Perception | 4.962 | 0.989 | 0.010 | 0.012 | −0.011 | −0.082 * | −0.041 | 0.397 ** | 0.504 ** | 1 | |

| 9. Managerial Coaching | 3.849 | 0.704 | 0.006 | −0.023 | 0.003 | −0.102 ** | −0.028 | 0.434 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.573 ** | 1 |

| 10. Trust | 3.817 | 0.939 | −0.031 | −0.005 | −0.059 | −0.058 | −0.029 | 0.344 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.413 ** |

| Study Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affective Organizational Commitment | 0.812 | ||||

| 2. Fairness Perception | 0.424 | 0.75 | |||

| 3. Managerial Coaching | 0.438 | 0.596 | 0.798 | ||

| 4. Trust | 0.401 | 0.475 | 0.442 | 0.772 | |

| 5. Thriving at Work | 0.498 | 0.484 | 0.543 | 0.34 | 0.709 |

| Paths | Effect | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP -> Thriving -> AOC | 0.131 | 0.0159 | 0.1015 | 0.1643 |

| MC -> Thriving -> AOC | 0.178 | 0.0203 | 0.1391 | 0.2189 |

| Trust -> Thriving -> AOC | 0.096 | 0.0196 | 0.0616 | 0.1363 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abid, G.; Contreras, F.; Ahmed, S.; Qazi, T. Contextual Factors and Organizational Commitment: Examining the Mediating Role of Thriving at Work. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174686

Abid G, Contreras F, Ahmed S, Qazi T. Contextual Factors and Organizational Commitment: Examining the Mediating Role of Thriving at Work. Sustainability. 2019; 11(17):4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174686

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbid, Ghulam, Francoise Contreras, Saira Ahmed, and Tehmina Qazi. 2019. "Contextual Factors and Organizational Commitment: Examining the Mediating Role of Thriving at Work" Sustainability 11, no. 17: 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174686

APA StyleAbid, G., Contreras, F., Ahmed, S., & Qazi, T. (2019). Contextual Factors and Organizational Commitment: Examining the Mediating Role of Thriving at Work. Sustainability, 11(17), 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174686