Abstract

This article analyzes legal regulations concerning access to public waters. Public waters are surrounded by property belonging to various owners. The legal title to property is exercised throughout that property, but certain limitations apply to properties situated in the proximity of public waters. These limitations include the right to cross the property, and public access to water. The article discusses various legal restrictions that permit third parties to use land. The presence of legal limitations in the national information system was verified. Information on restrictions in land use considerably affect the owner’s right to property, which is why owners should be able to determine whether their property is encumbered by an easement. National information systems are currently being upgraded in Poland, and the availability of information on land use restrictions was analyzed in the existing databases.

1. Introduction

The proximity of state-owned property that is accessible to the public can infringe on the rights of other property owners. The state makes its property accessible to members of the public. This standard practice applies to various types of state-owned land, including forests, water bodies, and other types of property intended for public use.

The rights exercised by the owners of property located adjacent to flowing bodies of water were subject to certain legal restrictions already under the Roman water law. Any citizen who owned land along the coast of the sea or the bank of a river had to bear with anyone who used the property for the purposes of fishing or transportation. These owners also had to allow fishermen or boatmen to tie their boats to trees in their land or unload their cargo there. Especially during the classical law period, all coastline and rivers were open to the use of all citizens. The praetorian interdictuti priori aestate did forbid anything to be built in a public river or its banks as this could cause the water to flow in a reverse direction than usual. Being a public law remedy, any Roman could resort to the praetor and invoke this interdict. The praetor could also compel the defendant to undo what he had done in the river or its banks with aninterdictum restitutium [].

Property can be owned privately as well as by the State. In Polish law, property is defined by various legal acts, including the Civil Code, the Act on Land and Mortgage Registers and on Mortgage, the Geodetic and Cartographic Law, and the Water Law []. State-owned property can be made available to the public, but public access to such property can also be restricted or prohibited. Considerable research has been done in Europe and the USA into the distinction between public and private property and the extent to which third parties are entitled to use land that does not constitute their property []. Ownership of real property entails the definition of land boundaries that should not be crossed by unauthorized parties. However, property boundaries can be crossed with the aim of accessing public waters. Public waters are defined as water bodies owned by the State, including inland surface waters. The definition of public waters varies across countries. The Polish Water Law [] defines public waters and the extent to which the boundaries of private property can be crossed and private property can be encroached upon to access public waters. “Public rights are just as essential to a healthy and functioning democratic society as are private rights” [], and water interests should belong to the public. By expanding the public trust doctrine to support a public stewardship model, the management and allocation of this unique common resource will be entrusted to the government for the public good [].

Access to public waters can be analyzed in the legal, technical, and functional context. Public waters can be accessed for recreational use, fishing, to satisfy the needs of households and agricultural farms, and for transportation. Public waters can be used for various purposes under the existing laws. The consequences of the lack of access to public waters have been broadly discussed in the literature [,,,,,,]. This article focuses on the legal regulations that create or prevent access to public waters.

2. Materials and Methods

The article analyzes legal regulations which provide third parties with access to public waters and the right to use private property. The analysis focuses on inland waters in selected countries. Access to coastal waters was not examined. Only public waters were investigated, and private bodies of water were excluded from the study.

The main research problem was to identify similar regulations concerning access to public waters. The applicable laws were analyzed in several countries characterized by different levels of economic development. The following countries were analyzed in this study: Poland, Netherlands, France, United Kingdom, and the United States of America. The selected countries follow two different legal systems: the civil law and the common law. Poland, Netherlands, France, and the UK are European Union members which have to incorporate EU regulations into their national legal systems. Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) [] was introduced to guarantee the consistency of spatial data in the EU Member States. According to Art. 288 of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [], a directive is binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but it leaves to the national authorities the choice of form and methods. A comparison of these forms and methods demonstrates the manner in which directives are implemented in the EU Member States, including the types of data that are displayed in the national geoportals. The countries that were selected for this study share certain characteristics which can be used to verify the research hypothesis. The USA was chosen for the analysis because water access in that country is regulated by the common law, and the relevant solutions provide valuable information de lege ferenda.

A relatively extensive set of source data was reviewed for comparison and detailed analysis. Legal restrictions applicable to property ownership were analyzed in the public registers of selected countries. Only systems and databases that can be accessed by the general public without logging in or creating a user account were taken into consideration. Various legal norms concerning access to public waters were reviewed and compared. The laws governing the ownership of water bodies, private access to public waters, and the access to national geoportals were compared.

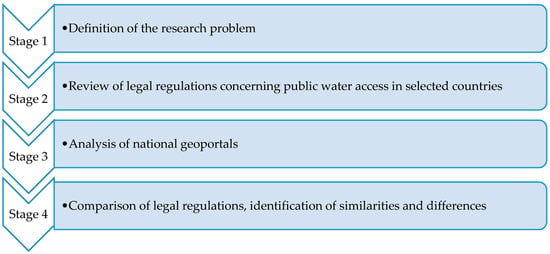

The stages of research are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A diagram of the research process. Source: Own elaboration.

The study relied on the formal dogmatic approach which is typically used in legal analyses. Legal regulations and case law were analyzed in several countries, and the relevant literature was reviewed. The aim of the study was to identify differences in legal acts concerning public water access.

3. Real Property Ownership

The right to property is classified as a human right. This right has evolved throughout history. In the Age of Enlightenment, human rights began to be perceived as rights that apply to individuals, rather than social groups or classes []. According to Locke, humans become entitled to a triad of rights, namely life, liberty, and property, at birth []. His primary contention was that property rights were self-evident rights []. Humans are free to exercise their property rights in any way they deem necessary and without the approval of others, as long as they observe the natural law. Property belongs to the owner who is free to protect his rights against other people []. When property rights are protected by State law, property owners cannot exercise their rights in a manner that violates the law. Therefore, when violations of property rights are penalized by the law, the owners should allow the State to interfere and enforce legal sanctions [].

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted at the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789. Art. XVII of the declaration states that “Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity” []. Property was construed as a law that can be restricted only under extraordinary circumstances pursuant to specific legal provisions. Before the French Revolution, only selected social classes were entitled to property rights. The declaration expanded property rights to all citizens regardless of their birth or status.

According to international documents and agreements, the right to property is a fundamental human right. These documents set forth the general rules regarding property rights as human rights and their protection. Various systems for the protection of human rights have been implemented, including international systems as well as regional conventions, such as those developed by the Council of Europe and the European Union. These systems and conventions set forth the principles for the acquisition, use, and enjoyment of property rights.

Many countries have implemented various legal instruments that guarantee the protection of property rights. In the Polish legal system, the relevant protective measures include the right to ascertain property ownership in court and the right to verify that the entry in the Land and Mortgage Register is consistent with the legal status of property [].

4. Laws Regulating Public Water Access in Selected Countries

4.1. Poland

In Poland, the management of national water resources is regulated by the Water Law of 20 July 2017. Inland waters are classified as bodies of flowing or standing water. Inland bodies of flowing waters include natural watercourses and their sources; lakes and other natural water bodies with continuous or periodic inflow or outflow of surface waters; artificial reservoirs developed in bodies of flowing water; and canals. Bodies of standing water include lakes and other natural water bodies that are not directly or naturally connected to inland bodies of flowing water. Inland bodies of flowing water constitute State property and are available to the public.

Pursuant to Art. 32 of the Water Law, all citizens have the right to use public inland bodies of surface water. Public waters may be used for various purposes, including to satisfy personal needs, to satisfy the needs of households and agricultural farms without the use of dedicated equipment, for recreation, tourism, water sports and, on the terms stipulated in separate regulations, for recreational fishing (Law, 2017, Art. 32). Public waters may be surrounded by private property. In such cases, the Water Law prescribes the terms on which the owners of private property adjacent to public waters can exercise their property rights.

To guarantee free access to public waters, a property owner is not allowed to fence off his property at a distance of 1.5 m from the shore line, and he may not forbid or block the public right of way. The Water Law; thus, imposes three restrictions on the owner of property that is located in the immediate vicinity of public waters (Law, 2017, Art. 232).

According to Art. 220 of the Water Law defines the shoreline as the edge of a water body, or the line between a water body and land that is permanently overgrown with grass, or a line that is defined based on the average water level over a minimum of 10 years. If the shoreline cannot be defined based on the average water level during the past 10 years, it can be defined by way of a binding decision. The defined shoreline is entered into the Land and Building Register. A property owner may not fence off his property at a distance of 1.5 m from the shoreline. The owner may not forbid or block access to public waters across the resulting strip of land, and he may not block the right of way across this part of property. A body of flowing water is thus surrounded by a strip of land with the width of 1.5 m which is accessible to the public.

Pursuant to the provisions of the Water Law, the owners of property adjacent to public waters are also under obligation to provide free access to public waters for the needs of water maintenance works, placement of navigation signs or hydrological and meteorological devices. Property owners who benefit from the installation of drainage devices and the owners of the adjacent land are obliged to provide free access to such devices during maintenance works. Property owners have to abide by the statutory limitations on the use of the owned property. Legal restrictions prevent owners from fully exercising their rights to property. The limitations applicable to the exercise of property rights are set forth by the Polish Civil Code. According to Art. 140 of the Civil Code, an owner may use his property, derive benefits and profits from his property, and dispose of the property.

The legal right of third parties to use private property significantly restricts an owner’s right to property. An owner should be in possession of full and valid information about the property’s status.

4.2. The Netherlands

In the Dutch Civil Code of 1992 [] (Art. 5:20), the ownership of land comprises the groundwater that comes to the surface naturally or through an installation, as well as the water above the soil, unless it has an open connection to water covering another owner’s land.

The owner of an immovable property adjoining public or streaming water may use that water for flushing, sprinkling and irrigating his land, for watering his cattle, or for similar purposes, provided that this does not cause nuisance to the owners of other premises to a degree or in a way which is unlawful []. The Dutch Civil Code also sets forth the principles for providing access to a public waterway. According to Art. 57, the owner of land that has no proper access to a public waterway may demand that the owner of neighboring land indicates the shortest possible access route over his land on behalf of the land that lacks access, against financial compensation.

When the boundary between two lands is situated in a lengthwise direction under a non-navigable flowing water, ditch, canal, or similar water stream, then each of the owners of these lands have the same rights and duties over the entire width (distance across) of that water stream as a co-owner. Every owner is compelled to maintain the embankment situated on his land [].

When land is not fenced off, it may be freely crossed by members of the general public, unless such passage causes damage to the owner’s property. The owner may prohibit members of the public from entering his property (Art. 22). The State is presumed to be the owner of the bottom of the territorial sea, beaches between the sea and the foot of the dunes, and the bottom of public waterways (Art. 26, 27).

Generally, it is prohibited to carry out activities such as building, excavating or planting greenery on, in, over or under water-related structures without the permission of the regional water authority.

4.3. France

According to Art. 538 of the French Civil Code [], navigable or floatable rivers and streams, beaches, foreshore, ports, harbors, anchorages, and generally all parts of French territory that do not constitute private property are deemed to be in the public domain. The owner of property adjacent to a body of water has the right to use that water and is the legal owner of the alluvium carried by water onto his property. When a considerable part of land is removed by a sudden drift of a river or a stream, the owner of the removed part of land may claim his property from the owner of the land to which the removed part has been joined (Art. 556–559). Islands in the beds of rivers or streams that are not navigable or floatable belong to the owners of property adjacent to those rivers or streams (Art. 560).

Rivers in France are divided into two categories: State rivers (rivières domaniales), where the river bed and the banks constitute public property, and non-public rivers (rivières non domaniales) whose banks belong to riparian owners. The majority of State rivers are waterways, but small rivers that used to be of national interest for shipping can also belong to the State. The water in watercourses is always a public good regardless of whether the watercourse constitutes State or private property []. All citizens have the right to use the water in watercourses, but this right does not extend to the banks of private rivers. The only exception are springs which belong to the property owner (Art. 641–642). An owner of property can draw water from a private river and build the required devices on his property (Art. 644).

The owners of property adjacent to a public stream or river are legally obliged to permit fishing to persons with a finish license and to leave a space with a width of 3.5 m along the river bank for right of passage and fishing sites. For fishing purposes, this space can be reduced to 1.5 m by the local prefecture [].

4.4. Common Law Countries

It is worth considering whether the rules in the common law system countries are uniform and guarantee public access to water. Since the size of the study does not allow the analysis of a larger number of legal solutions, only the British and American systems will be analyzed. It should also be noted that American law is largely modeled on the British law and uses the British case law as its own (See: The common law of England upon this subject at the time of the emigration of our ancestors is the law of this country, except so far as it has been modified by the charters, constitutions, statutes, or usages of the several colonies and states, or by the Constitution and laws of the United States. Shively v. Bowlby, 152 U.S. 1, 14 (1894)), but the conditions for the creation of the law relating to public access to waters were much different in the US than in the United Kingdom. Hence, it could be expected that legal solutions will diverge from each other.

4.4.1. The United States of America

In general, the American concept of revised common law provided that water was available for anyone to take and use—there was no exclusive right for those buying land covered by water []. In contrast, there was no right in water itself in English law, instead there were rights to land covered with water []. Legislative solutions that differentiated the use of water in particular states evolved over time, leading to the creation of the English concept of riparian rights and the American concept of appropriation.

However, American approaches usually focused on the holder of the ownership title and the property itself: Is it the private owner who holds a title only to the beds of non-navigable waters with a title to the latter in the state or the United States, or to the beds of all inland waters, navigable or non-navigable, while the public has a right of passage, but only in case of navigable waters, or, inversely, is it the state that has a title to the bed and cannot dispose of it to anyone []. This gave rise to two lines of court decisions concerning the range of riparian rights in general. In the former case, the riparian owners enjoy their rights to the center of the main channel of the stream, subject to the public rights to navigate such stream. In the latter, ownership extends to the high-water mark or the low-water mark, while the state owns the bed of the stream and the shore below the high-water mark or the low-water mark [].

The Latin word ripa means a river bank []. In the American and English Encyclopedia of Law, Alexander Stronach defined riparian rights as the rights that are attached to the ownership of land through, or past which, a river runs (Then he writes: The rights of owners of land bounded by or abutting on the sea or great lakes are, more properly speaking, denominated littoral rights, but these terms are frequently used interchangeably; the word littoral comes from the Latin word litus (sea-shore)) [,]:

- The right to use the stream in connection with riparian land (Weston v. Alden, 8 Mass. 136 (1811));

- The right to free and unobstructed flow of the stream onto his land (Corse v. Dexter, 202 Mass. 31, 88 N.E. 332 (1909); New England Cotton Yarn Co. v. Laurel Lake Mills, 190 Mass. 48, 76 N.E. 231 (1906); Ware v. Allen, 140 Mass. 513, 5 N.E. 629 (1886); Merrifield v. Lombard, 95 Mass. (13 Allen) 16 (1866)) and from it (DiNardo v. DoVidio, 312 Mass. 398, 45 N.E.2d 269 (1942), McGowen v. Carr, 272 Mass. 573, 172 N.E. 787 (1930));

- The right to ordinary and reasonable use (any lawful and beneficial use that is not inconsistent with the reasonable use by other riparians) (Amory v. Commonwealth, 321 Mass. 240, 72 N.E.2d 549 (1947); Stratton v. Mt. Hermon Boys’ School, 216 Mass. 83, 103 N.E. 87 (1913). See Petraborg v. Zontelli, 217 Minn 536, 15 NW 2d 174 [1944]) of the water flowing in the watercourse, for domestic purposes and for watering livestock (even if it interferes with the water use rights of a downstream riparian owner);

- The right to extraordinary use of water, but only if it does not interfere with the rights of other riparian owners above or below (i.e., for keeping meadows moist and productive) ([]; []; []) (See: Embrey v Owen (1851) 6 Ex 353 (per Parke B); Miner v Gilmour (1859) 12 Moo. PCC 131; Chasemore v Richards (1859) 7 HL Cas 349);

- The right of navigation, boating, swimming, docking;

- The right of fishing (riparian’s exclusive right to non-navigable waters, which has to be shared with the public, as far as public access to water is concerned, in navigable waters [];

- The right to use the land added by accretion or exposed by reliction;

- The right to the alluvium deposited by the water;

- The right to build wharves and docks [];

- The right to take ice (See also Sanborn v. People’s Ice Co. 82 Minn 43, 84 NW 641 [1900] and Lamprey v. State, 52 Minn 181, 53 NW 1139 [1883]);

- The right to make use of the lake over its entire surface (Johnson v. Seifert 257 Minn 159, 100 NW 2d 689 [1960]).

Traditionally‚ every riparian owned the portion of a non-navigable river bed which adjoined his land usque ad filum aquae (i.e., to the central line or the middle of the stream) []. Riparians owning both banks of a non-navigable stream were entitled to private ownership of the stream with exclusive fishing rights (State ex rel State Game Comm. v Red River Valley Co., 51 NM 207, 182 P2d 421 (1945)). Riparian rights do not apply when a title extends only to the water’s edge (Osceola County v Triple E. Dev. Co. (Fla) 90 S2d 600 (1956)). Regardless of the size and attributes of their property, riparians could not dike off, drain, or fence off their part of the water []. Any infringement of property rights was regarded as trespass (Bino v City of Hurley, 273 Wis 10, 76 NW2d 571 (1956)) and the most controversial issue were not water rights, but the right of way through the lands of the United States (See Utah Power & Light Co. v. United States, 230 F 328, 337 (8th Cit. 1915)) [].

The legal solutions in selected US states are presented in Table 1 to illustrate various approaches to the ownership of water bodies and the public right of way through private property adjacent to water.

Table 1.

Laws governing access to water bodies in selected US states.

The above table indicates that the US’ states can pass their own laws regulating the ownership of water bodies, the use of water resources, and the public right of way through private property to access water bodies. In common law countries, case law derived from judicial decisions has a considerable impact on future cases and the shape of the law.

4.4.2. The United Kingdom

According to Maritime and Coastguard Agency, the UK presently has over 4000 miles of inland waterways, which include any area of water not categorized as sea: canals, tidal and non-tidal rivers, lakes, and some estuarial waters (arms of sea that extend inland to meet the mouth of a river). These water bodies are classified into four categories: A—narrow rivers and canals where the depth of water is less than 1.5 m; B—wider rivers and canals where the depth of water is 1.5 m or more and where the significant wave height could not be expected to exceed 0.6 m at any time; C—tidal rivers, estuaries, and large, deep lakes and lochs where the significant wave height could not be expected to exceed 1.2 m at any time; D—tidal rivers and estuaries where the significant wave height could not be expected to exceed 2 m at any time [].

The Scottish law provides a right of responsible, non-motorized access to all land and inland water in Scotland. According to Scottish Land Reform Act of 2003 [], everyone has statutory access rights to be, for any of the purposes set in the act, on land and to cross land. The former may be exercised only for recreational purposes, for the purposes of carrying on a relevant educational activity, or for the purposes of carrying on, commercially or for profit, an activity which the person exercising the right could carry on otherwise than commercially or for profit. Access rights are exercisable above and below (as well as on) the surface of the land. A person has access rights only if they are exercised responsibly. In determining whether access rights are exercised responsibly, a person is to be presumed to be exercising access rights responsibly if they are exercised so as not to cause unreasonable interference with any of the rights (whether access rights, rights associated with the ownership of land or any others) of any other person. The land in respect of which access rights are not exercisable is land: (a) To the extent that there is on it: (i) A building or other structure or works, plant or fixed machinery, (ii) a caravan, tent or other place affording a person privacy or shelter; (b) which: (i) Forms the curtilage of a building which is not a house or of a group of buildings none of which is a house, (ii) forms a compound or other enclosure containing any such structure, works, plant or fixed machinery, (iii) consists of land contiguous to and used for the purposes of a school or (iv) comprises, in relation to a house or any of the places mentioned in paragraph (a) (ii) above, sufficient adjacent land to enable persons living there to have reasonable measures of privacy in that house or place and to ensure that their enjoyment of that house or place is not unreasonably disturbed; (c) to which, not being land within paragraph (b) (iv) above, two or more persons have rights in common and which is used by those persons as a private garden; (d) to which public access is, by or under any enactment other than this Act, prohibited, excluded, or restricted; (e) which has been developed or set out (i) as a sports or playing field or (ii) for a particular recreational purpose; (f) to which: (i) For not fewer than 90 days in the year ending on 31st January 2001, members of the public were admitted only on payment and (ii) after that date, and for not fewer than 90 days in each year beginning on 1st February 2001, members of the public are, or are to be, so admitted; (g) on which: (i) Building, civil engineering or demolition works or (ii) works being carried out by a statutory undertaker for the purposes of the undertaking, are being carried out; (h) which is used for the working of minerals by surface workings (including quarrying); (i) in which crops have been sown or are growing; (j) which has been specified as land in respect of which access rights are not exercisable. The owner of land in respect of which access rights are exercisable shall not, for the purpose or for the main purpose of preventing or deterring any person entitled to exercise these rights from doing so: (a) Put up any sign or notice; (b) put up any fence or wall, or plant, grow, or permit to grow any hedge, tree, or other vegetation; (c) position or leave at large any animal; (d) carry out any agricultural or other operation on the land; or (e) take, or fail to take, any other action. The act also provides for the creation of two systems that enable the execution of rights, or at least make the statute regulation more practical: A system of core paths together with a detailed overview map, and the Scottish Outdoor Access Code. Both systems are sources of public information, and the latter additionally defines responsible access []. According to the leaflets printed by the local government, a core path can be a right of way, a farm track, an old drove road, a route published in a guidebook, or any location with a route on the ground or water, as well as any location without such routes, including elements of an old network of paths regulated by common law [] that are referred to as the right of way. The core paths should be signposted at key access points, all boundary crossings—gates, stiles and gaps through fences, hedges and walls—should be accessible to all legitimate users, and the path surfaces can be anything from grassy country paths to tarmac-surfaced paths [].

In Wales, the right to access applies to lands designated as open access, public footpaths, and other public rights of way (bridleways, byways) classified as long distance routes, woodlands, and national nature reserves [].

5. Geoportals as Information Systems

Land administration systems (LASs) are implemented to support land management. These systems facilitate the implementation of land policies and land management strategies to promote sustainable development and management, and they are a source of spatial data on land rights, restrictions and responsibilities []. Land administration systems should be planned in a manner that meets various social needs, secures property rights, and promotes the implementation of sustainable land policies. The term “fit-for-purpose” is closely linked with the development of sustainable LASs []. National LASs differ in the scope of the presented data, and they are also developed in a different manner.

Pursuant to the INSPIRE Directive of the European Commission, the central and local governments of the EU Member States are under obligation to implement a common course of action in the development of real property information systems, including the introduction of uniform vocabulary and technology. The harmonization of legislation and spatial data sets was a considerable and multi-dimensional effort. The INSPIRE Directive is a legal instrument promoting the harmonization of data sets for joint use. The flow of data between various data sets should not be obstructed by technical or functional differences. Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) (OJ L 108, 25 April 2007) The Annexes to the INSPIRE Directive specify the types of spatial data relating to water resources that have to be indicated in the national databases.

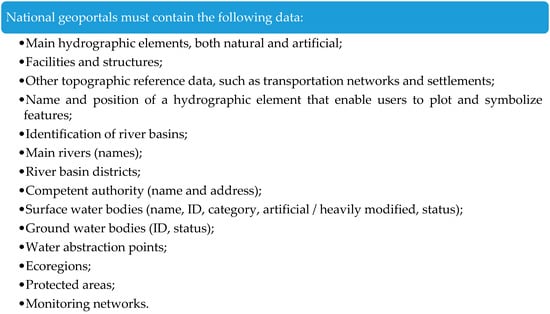

The INSPIRE Directive does not impose strict technical guidelines relating to the implementation of the LASs in different countries, but merely proposes the most effective models for achieving the interoperability of spatial data and services. European countries are not under obligation to keep their databases in an identical manner. The countries implementing the provisions of the INSPIRE Directive develop LASs, including geoportals where geographic data can be visualized in maps. The manner in which spatial data are presented in national geoportals is selected individually by every country. However, all geoportals have to feature the information specified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Types of spatial data relating to water resources that have to be indicated in the national databases.

These types of spatial data (Figure 2) can be presented in thematic layers or separate maps in national geoportals. The INSPIRE Geoportal website [] lists European geoportals and the types of metadata presented by each geoportal. The website contains links to national geoportals. The laws regulating water resources in the US were discussed in this article, and the American geoportal was also analyzed.

Figure 2.

Types of spatial data that must be included in national geoportals. Source: Own elaboration.

The following national geoportals were analyzed:

- Netherlands—https://www.pdok.nl/viewer/#

- United Kingdom—https://data.gov.uk/location

- Switzerland—https://www.geo.admin.ch/

In the analyzed geoportals, the information about water resources is visualized with the use of different approaches, such as thematic layers and separate thematic maps. Only technical data is presented, and legal information is not available. The information about the ownership status of waters and legal restrictions applicable to property adjacent to a body of water is not provided. The analyzed geoportals contain flood hazard maps, which enable users to determine whether their property is at risk of flooding. Selected geoportals, including the Dutch and German geoportals, contain information about public waterways and navigable water routes.

The Swiss geoportal deserves special attention in the group of the analyzed European websites. It contains information about the surface area, quality, biological parameters, catchment areas, drainage basins, and conservation status of rivers and lakes. The scope of spatial data relating to water resources in the Swiss geoportal complies with the requirements of the INSPIRE Directive. The geoportal features a highly intuitive user interface. Spatial data can also be displayed in 3D format.

The Polish geoportal displays the spatial data aggregated by the National Water Management Authority. These data were previously available in a dedicated information system that was kept and made available to users on the website of the National Water Management Authority. The system was incorporated into the Polish national geoportal upon the implementation of the INSPIRE Directive. At present, the national geoportal is the only source of spatial data required by the INSPIRE Directive [].

The US geoportal contains information about water resources, but the relevant data are displayed differently than in the European geoportals. The website does not feature thematic layers or maps that have been incorporated into the national geoportal, but it constitutes a dedicated site of the US Geological Survey. The displayed information includes the number, name, type, location, and surface area of water bodies, as well as the responsible agencies. Users can filter data to obtain information about water levels in different time periods.

In Europe, the required types of spatial data relating to water resources are specified by the INSPIRE Directive. The relevant information can be displayed in a different manner in national geoportals. Some countries display additional data that are not compulsory within the context of the INSPIRE Directive. However, none of the analyzed geoportals provide information about water rights, including the legal status of water bodies, or the legal restrictions and riparian rights awarded to land owners whose property is located in the immediate vicinity of water bodies.

The EU Member States are not legally obliged to provide information about property rights and restrictions in national geoportals. Property rights can also be encumbered by legal liabilities that are not related to water resources. Some encumbrances, such as easements, are revealed in land registers and cadasters.

The implementation of the 3D cadaster can resolve the above problem. The concept of the 3D cadaster has been widely discussed in the literature [,,,,,,,,,]. Its implementation will bring about important changes by introducing the concept of property rights in 3D space. The 3D cadaster will represent complete and comprehensive spatial information not only about land rights, but also about the restrictions and responsibilities imposed on property owners. The National Conservation Easement Database [] is the first national database of conservation easement information which compiles records from various sources and public agencies in the United States. However, property owners are not identified in the database, and only information that is available from the cadaster and private owners, such as easement boundaries, purpose and holder profiles, is disclosed. Users can filter data resources based on property rights, owner profile, type of access, and conservation goal.

The above solution indicates that the development of a database containing information about property rights as well as restrictions and responsibilities over land is not an impossible undertaking. For this goal to be achieved, spatial data have to be combined with property information and displayed in the cadaster. The 3D cadaster will be a useful tool, providing information about legal restrictions on the use of land.

6. Discussion

Water bodies have different legal status in various countries (Table 3). In the USA, the respective legal regulations also differ among the states. Land covered by surface waters has different ownership status. Some countries guarantee unlimited access to public waters, which are also open to public use. However, the information about the legal status of water bodies is not available in national geoportals. Most geoportals contain technical data about water bodies, but do not disclose their owners. As a result, members of the public cannot ascertain whether a given body of water constitutes State or private property. Information about the legal status of property covered by or adjacent to water bodies as well as the resulting restrictions on property rights is essential not only for public administration, but also for individuals. The incorporation of data describing the legal status of property, at least indicating whether it is public or private, can facilitate land management, transfer of property rights and other operations involving real estate. Many land owners are prevented from freely managing property that is located in the direct vicinity of water. In some cases, properties that are subject to legal restrictions cannot be developed or fenced off. Some riparian owners are legally obliged to obtain the relevant permits from the responsible authorities.

Table 3.

Synthetic presentation of access to public waters in selected countries.

Land owners require comprehensive information about the legal status of their property to effectively secure their property rights. Databases containing information about flood hazards are one of the tools that support effective protection of property.

National geoportals do not display information about the legal status of water bodies. The planned 3D cadaster will combine spatial data with information about property rights and restrictions that have been entered into land registers and other integrated systems, including the cadaster. The 3D cadaster is currently being developed by the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG). Modern cadastral systems should serve a variety of purposes other than land taxation and the management of land ownership records [,].

The information about the legal status of water bodies, public water access, and the right to water resources are presented differently in the analyzed countries and states. Those variations can be attributed to historical factors and the evolution of different legal systems. At present, legal acts and court verdicts are the only sources of information about potential land use restrictions for property owners. The rights and restrictions applicable to water bodies and the adjacent property are not disclosed in the existing databases or systems. The relevant data can be obtained from the LASs. In the implemented LASs, the information about land ownership (even if the land owners’ identity is not disclosed) should be disseminated to the public. As a result, land owners will have access to comprehensive information about their property. The relevant data will also benefit other users who require information about public water bodies and the existing access routes.

The LASs should be a source of information about property rights and restrictions not only for land owners and tenants, but also for other interested parties. Therefore, the existing LASs should be modified or expanded to display information about property rights and the restrictions and responsibilities over land.

The proposed solution will be initially verified on public surface waters. These waters are owned by the State; therefore, the relevant rights can be analyzed without infringing on the interests of private owners. The solution can be applied to all types of water bodies, but the particulars of owners and entities holding other rights to public waters will have to be kept anonymous.

Author Contributions

A.K., K.B.-K. and M.P. conducted the research, A.K. K.B.-K. and M.P. developed the research concept, Ź.Z. reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research prepared under the statutory research No. 28.610.020-300.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saym, Y.; Lehavi, A.; Oder, B.E.; Önok, M.; Francavilla, D.; de Silva, V.T.; Sudarshan, R. Land Law and Limits on the Right to Property: Historical, Comparative and International Analysis. Law Sch. Glob. Leag. Res. Pap. Ser. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chruściel, M. Formalno-prawne ujawnienie prawa własności w obrocie nieruchomościami. Studia z Zakresu Prawa Administracji I Zarządzania. UKW 2013, 4, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. Emerging Issue: Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning: Beach Access, Trespass, and the Social Enactment of Property. Roger Williams Univ. Law Rev. 2012, 17, 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- The Polish Water Law. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20170001566/U/D20171566Lj.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Brown, C.N. Drinking from a Deep Well: The Public Trust Doctrine and Western Water Law. Fla. State Univ. Law Rev. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxer, S.R. The Fluid Nature of Property Rights in Water. Duke Envtl. L. Pol’y F 2010, 21, 49–112. [Google Scholar]

- Laura, W.; Matodzi, M.M.; Lutendo, S.M.; Jo-Anne, G. Factors that impact on access to water and sanitation for older adults and people with disability in rural South Africa: An occupational justice perspective. J. Occup. Sci. 2017, 24, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.P.; Van Koppen, B.; Van Houweling, E. The human right to water: The importance of domestic and productive water rights. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2014, 20, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armar-Klemesu, M. Thematic paper 4: Urban agriculture and food security, nutrition, and health. In Growing Cities Growing Food: Urban Agriculture on the Policy Agenda: A Reader on Urban Agriculture; Bakker, N., Dubbeling, M., Guendel, S., Sabel Koschella, U., de Zeeuw, H., Eds.; DSE: Feldafing, Germany, 2000; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bluemel, E.B. The implications of formulating a human right to water. Ecol. Law Q. 2005, 31, 957–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.H. Basic water requirements for human activities: Meeting basic needs. Water Int. 1996, 21, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H. The human right to water. Water Policy 1998, 1, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.P.; Van Houweling, E.; Vance, E.; Hope, R.; Davis, J. Assessing the link between productive use of domestic water, poverty reduction, and sustainability. In Senegal Country Report; Virginia Tech.: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2011; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 Establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE); European Parliament and of the Council of the European Union: Brussel, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012E%2FTXT (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Hołda, J.; Hołda, Z.; Ostrowska, D.; Rybczyńska, J.A. Prawa Człowieka. Zarys Wykładu; Wolters Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. Dzieje Filozofii Zachodu; Fundacja Aletheia: Warsaw, Poland, 2000; p. 1014. [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of France. Available online: http://libr.sejm.gov.pl/tek01/txt/konst/francja-18.html (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Czerwińska-Koral, K. Ochrona prawa własności, czyli roszczenia przysługujące właścicielowi na podstawie przepisów kodeksu cywilnego. Rocz. Adm. i Prawa 2014, 14, 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Civil Law. Available online: http://www.dutchcivillaw.com/civilcodebook055.htm (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- France Civil Code. Available online: https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/text/450530 (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Richard, S.; Bouleau, G.; Barone, S. Water governance in France. Institutional framework, stakeholders, arrangements and process. In Water Governance and Public Policies in Latin America and Europe; Jacobi, P., Sinisgali, P., Eds.; Anna Blume: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2010; pp. 137–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lakes France. Available online: https://www.lakesfrance.com/fishing (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Freyfogle, E.T. Property Law in a Time of Transformation: The Record of the United States. S. Afr. L.J. 2014, 131, 883. [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray, D. Water Rights and Environmental Damage: An Enquiry into Stewardship in the Context of Abstraction Licensing Reform in England and Wales. Environ. Law Rev. 2013, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, F.; Clark, G.; John, S. Treatise on the Law of Surveying and Boundaries; The Bobbs-Merrill Company Publishers: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1959; p. 676. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, J.M. Treatise on the Law of Waters, including Riparian Rights, and Public and Private Rights in Waters Tidal and Inland; TheClassics.us: Chicago, IL, USA, 1900; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- David, S.; Lucius, P. American and English Encyclopaedia of Law; Edward Thompson Co.: Northport, NY, USA, 1896–1905; p. 978. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, E.A.; Wermuth, W.C. Modern American Law; Blackstone Institute: Chicago, IL, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, W. Burge’s Commentaries on Colonial and Foreign Laws; Alexander, W.R., George, G.P., Eds.; Sweet & Maxwell: London, UK, 1914; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Wiel, S.C. Water Rights in the Western States; Arno Press: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Water Law Basics. Available online: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/watermgmt_section/pwpermits/waterlaws.html (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Smith, J.C. This Land Is Your Land; But What about My Water; Applying an Exaction Analysis to Water Dedication Requirements for Facilities on Federal Land. Wyo. Law Rev. 2014, 14, 1. [Google Scholar]

- The Office of the Revisor of Statutes. Available online: https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/103G.005 (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- History of Water Protection. Available online: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/watermgmt_section/pwpermits/history.html (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Updated GIS-Based PWI Maps in an Electronic Format (Portable Document Format—PDF) Should be Available to the Public—They Replace a Scanned Paper PWI Maps. Public Waters Inventory (PWI) Maps. Available online: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/watermgmt_section/pwi/maps.html (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Haar, C.M.; Gordon, B. Riparian Water Rights vs. a Prior Appropriation System: A Comparison. Boston Univ. Law Rev. 1958, 38, 207–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood, F. Who Owns Alabama’s Coosa River: Citizens’ Impact on the Tri-State Water Wars Muted by Private Ownership of Riparian Rights. Va. Environ. Law J. 2016, 34, 230–254. [Google Scholar]

- The Constitution of the State of Montana. Available online: https://courts.mt.gov/portals/189/library/docs/72constit.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Russell, I.S. Evolving Water Law and Management in the U.S.: Montana. Univ. Denver Water Law Rev. 2016, 20, 48. [Google Scholar]

- 2017 Oregon Revised Statutes. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/oregon/2017/volume-13/chapter-537/ (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Oregon Water Resources Department. Water Rights in Oregon. An Introduction to Oregon’s Water Laws. November 2013 Revised; p. 5. Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/OWRD/WRDPublications1/aquabook.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Cloran, W.F. The Ownership of Water in Oregon: Public Property vs. Private Commodity. Willamette Law Rev. 2011, 47, 627–672. [Google Scholar]

- Guidance. Inland Waterways and Categorisation of Waters. Details for Owners, Operators and Masters of Vessels on Inland Waters, including Categorisation, how to Apply, Safety Requirements and Best Practice. Published 14 September 2012, Last updated 21 November 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/inland-waterways-and-categorisation-of-waters (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Land Reform Scotland. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2003/2/part/1/chapter/1 (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Outdoor Access Scotland. Available online: https://www.outdooraccess-scotland.scot/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Stirling Council. Available online: https://my.stirling.gov.uk/planning-building-the-environment/environment/core-paths/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Where Can I Walk in Wales? Available online: https://naturalresources.wales/days-out/things-to-do/walking/?lang=en (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Dawidowicz, A.; Źróbek, R. A methodological evaluation of the Polish cadastral system based on the global cadastral model. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, S.; Bell, K.C.; Lemmen, C.; McLaren, R. Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration; International Federation of Surveyors (FIG): Copenhagen, Denmark; Jensen Print: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2014; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- D2.8.I.8 Data Specification on Hydrography—Technical Guidelines. p. 14. Available online: https://inspire.ec.europa.eu/id/document/tg/hy (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Inspire Geoportal. Available online: http://inspire-geoportal.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Klimach, A.; Dawidowicz, A.; Dudzińska, M.; Ryszard Źróbek, R. An evaluation of the informative usefulness of the land administration system for the Agricultural Land Sales Control System in Poland. J. Spat. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoter, J.; Ploeger, H.; Roes, R.; van der Riet, E.; Biljecki, F.; Ledoux, H. First 3D Cadastral Registration of Multi-Level Ownerships Rights. In Proceedings of the Netherlands 5th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop, Athens, Greece, 18–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, M.; Rajabifard, A.; Wallace, J.; Williamson, I. Spatially referenced legal property objects. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsakis, D.; Dimopoulou, E. 3D Cadastres: Legal Approaches and Necessary Reforms. Surv. Rev. 2014, 46, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsakis, D.; Paasch, J.; Paulsson, J.; Navratil, G.; Vučić, N.; Karabin, M.; Carneiro, A.F.T.; El-Mekawy, M. 3D Real Property Legal Concepts and Cadastre—A Comparative Study of Selected Countries to Propose a Way Forward. In Proceedings of the 5th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop, Athens, Greece, 18–20 October 2016; Available online: http://www.gdmc.nl/3dcadastres/literature/3Dcad_2016_11.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2018).

- Karabin, M. Registration of the Premises in 2D Cadastral System in Poland. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2011 “Bridging the Gap between Cultures”, Marrakech, Morocco, 18–22 May 2011; Article No 4818. Available online: www.oicrf.org (accessed on 23 April 2018).

- Karabin, M. A Concept of a Model Approach to the 3D Cadastre in Poland. Ph.D. Thesis, Warsaw University of Technology, Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Warszawskiej, Warsaw, Poland, May 2013. Scientific Work—Geodesy Series, Number of Book 51. 116p. [Google Scholar]

- Karabin, M. A concept of a model approach to the 3D cadastre in Poland—Technical and legal aspects. In Proceedings of the 4th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop, Dubai, UAE, 9–11 November 2014; Van Oosterom, P., Fendel, E., Eds.; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Bydłosz, J.; Czaja, S.; Dawidowicz, A.; Gajos, M.; Jasiołek, J.; Jasiołek, K.; Jokić, M.; Križanović, K.; Kwartnik-Pruc, A.; Łuczyński, R.; et al. Transition of 2D Cadastral Objects into 3D Ones—Preliminary Proposal; Źróbek, R., Ed.; Management of Real Estate Resources: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bydłosz, J. Developing the Polish Cadastral Model towards a 3D Cadastre. In Proceedings of the 5th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop, Athens, Greece, 18–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Siejka, M.; Ślusarski, M.; Zygmunt, M. 3D + time Cadastre, possibility of implementation in Poland. Surv. Rev. 2014, 46, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Conservation Easement Database. Available online: https://www.conservationeasement.us (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Enemark, S. Land administration infrastructures for sustainable development. Prop. Manag. 2001, 19, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pietkiewicz, M. The main directions of EU environmental strategy. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference (SGEM), Surveying Geology & Mining Ecology Management (SGEM), Sofia, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017; Volume 17, pp. 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).