Effects of Indoor Plants on Self-Reported Perceptions: A Systemic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.8. Summary Measure

3. Results

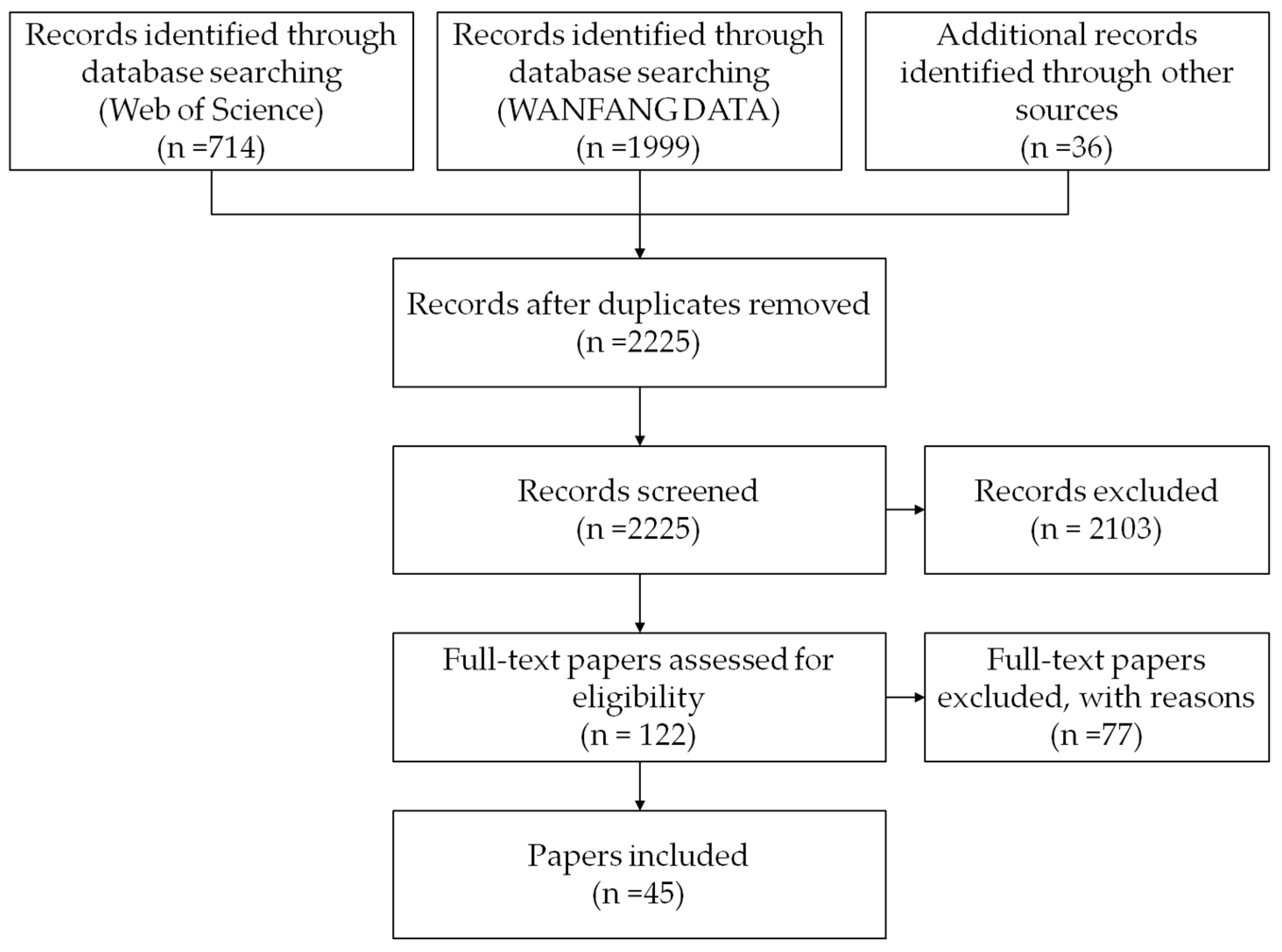

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Results of Individual Studies

3.4. Additional Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Lung Association. When You Can’t Breathe, Nothing Else Matters. Air Quality. 2001. Available online: www.lungusa.org/air/ (accessed on 27 September 2017).

- Dravigne, A.; Waliczek, T.M.; Lineberger, R.; Zajicek, J. The Effect of Live Plants and Window Views of Green Spaces on Employee Perceptions of Job Satisfaction. HortScience 2008, 43, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardon, R.C. Perception and aesthetics of the urban environment: Review of the role of vegetation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1988, 15, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaker, G.H. Interior Plantscapes: Installation, Maintenance, and Management, 3rd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, J.S.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. The Impact of Interior Plants in University Classrooms on Student Course Performance and on Student Perceptions of the Course and Instructor. HortScience 2009, 44, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.T. Influence of passive versus active interaction with indoor plants on the restoration, behavior, and knowledge of students at a junior high school in Taiwan. Indoor Built Environ. 2018, 27, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.T. Urban Forestry: Theories and Applications; Lamper: Taipei, Taiwan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, M.V.D.; Sang, Å.O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—A systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systemic review and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What Are the Most Spoken Languages in the World? Available online: https://www.fluentin3months.com/most-spoken-languages/ (accessed on 29 July 2019).

- Han, K.T. Restorative Nature: An. Overview of the Positive Influences of Natural Landscapes on Humans; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, H.J. Quantitative Research and Statistical Analysis in Social & Behavioral Sciences; Wunan Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort-Nachmias, C.; Nachmias, D. Reasearch Methods in the Social Sciences; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Quasi-Experimentation: Design & Analysis issues for Field Settings; Hougton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, L.; Adams, J.; Deal, B.; Kweon, B.S.; Tyler, E. Plants in the workplace: The effects of plant density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J.P.T., Green, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2008; pp. 187–241. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kim, E.; Mattson, R.H. Physiological and emotional influences of cut flower arrangements and lavender fragrance on university students. J. Ther. Hortic. 2003, 14, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.E. Interior office and visitor response. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979, 64, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, V.I.; Pearson-Mims, C. H.; Goodwin, G.K. Interior plants may improve worker productivity and reduce stress in a windowless environment. J. Ther. Hortic. 1996, 14, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fjeld, T.; Veiersted, B.; Sandvik, L.; Riise, G.; Levy, F. The Effect of Indoor Foliage Plants on Health and Discomfort Symptoms among Office Workers. Indoor Built Environ. 1998, 7, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Rohde, C.; Kendle, A.D. Effects of Floral and Foliage Displays on Human Emotions. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeld, T. The Effect of Interior Planting on Health and Discomfort among Workers and School Children. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, V.I.; Pearson-Mims, C.H. Physical Discomfort May Be Reduced in the Presence of Interior Plants. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Mattson, R.H. Stress recovery effects of viewing red-flowering geraniums. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H.; Mattson, R.; Kim, E. Pain tolerance effects of ornamental plants in a simulated hospital patient room. Acta Hortic. 2004, 639, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Suzuki, N. Effects of an indoor plant on creative task performance and mood. Scand. J. Psychol. 2004, 45, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Younis, A.; Riaz, A.; Abbas, M.M. Effect of interior plantscaping on indoor academic environment. J. Agric. Res. 2005, 43, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. Psychological Benefits of Indoor Plants in Workplaces: Putting Experimental Results into Context. HortScience 2007, 42, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, K.; Pieterse, M.; Pruyn, A. Stress-reducing role of perceived attractiveness. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Mattson, R.H. Effects of Flowering and Foliage Plants in Hospital Rooms on Patients Recovering from Abdominal Surgery. HortTechnology 2008, 18, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Song, J.S.; Kim, H.D.; Yamane, K.; Son, K.C. Effects of Interior Plantscapes on Indoor Environments and Stress Level of High School Students. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 77, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Han, K.T. Influence of limitedly visible leafy indoor plants on the psychology, behavior, and health of students at a junior high school in Taiwan. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 658–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.W.; Kim, H.H.; Yang, J.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, D.C. Improvement of Indoor Air Quality by Houseplants in New-built Apartment Buildings. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2009, 78, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Mattson, R.H. Therapeutic Influences of Plants in Hospital Rooms on Surgical Recovery. HortScience 2009, 44, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.Y.; Han, K.T. The Influence of Classroom Greening on Students’ Physical Psychology and Academic Performance-Taking Xinguang Guozhong in Taichung County as an Example. Sci. Agric. 2010, 58, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.H.; Park, J.W.; Yang, J.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, D.C.; Lim, Y.W. Evaluating the Relative Health of Residents in Newly Built Apartment Houses according to the Presence of Indoor Plants. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 79, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raanaas, R.K.; Patil, G.G.; Hartig, T. Effects of an Indoor Foliage Plant Intervention on Patient Well-being during a Residential Rehabilitation Program. HortScience 2010, 45, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.T.; Hung, C.Y. Influences of plants and their visibility, distance, and surrogate in a classroom on students’ psycho-physiology. J. Archit. Plann. 2011, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Yang, J.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Shin, D.C.; Lim, Y.W. Evaluation of Indoor Air Quality and Health Related Parameters in Office Buildings with or without Indoor Plants. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2011, 80, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brengman, M.; Willems, K.; Joye, Y. The Impact of In-Store Greenery on Customers. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.T.; Hung, C.Y. Influences of physical interactions and visual contacts with plants on students’ psycho-physiology, behaviors, academic performance and health. Sci. Agric. 2012, 59, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, M.; Jiang, D.Y.; Wang, J.; Lv, Y.M.; Zhang, Q.X.; Pan, H.T. Effects of plantscape colors on psycho-physiological responses of university students. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 702–708. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lu, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Pan, H.T.; Zhang, Q.X. The visual effects of flower colors on university students psycho-physiological responses. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Elsadek, M.; Sayaka, S.; Fujii, E.; Koriesh, E.; Moghazy, E.; Elfatah, Y. A. Human emotional and psycho-physiological responses to plant color stimuli. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, K.J.; Park, J.H.; Shin, D.C.; Lim, Y.W. Impact of Foliage Plant Interventions in Classrooms on Actual Air Quality and Subjective Health Complaints. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 82, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.B.; Zhang, X.J.; Zhou, X.; Sun, C.J.; Qin, J.; Lian, Z.W. Relationship between dominant feature of indoor plants and indoor environment satisfaction. J. Environ. Health 2013, 30, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Elsadek, M.; Fujii, E. People’s psycho-physiological responses to plantscape colors stimuli: A pilot study. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.S.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.S.; Pak, C.H. Human brain activity and emotional responses to plant color stimuli. Color Res. Appl. 2014, 39, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangone, G.; Kurvers, S.; Luscuere, P. Constructing thermal comfort: Investigating the effect of vegetation on indoor thermal comfort through a four season thermal comfort quasi-experiment. Build. Environ. 2014, 81, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.; Knight, C.; Postmes, T.; Haslam, S.A. The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: Three field experiments. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2014, 20, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Sun, C.; Zhou, X.; Leng, H.; Lian, Z. The effect of indoor plants on human comfort. Indoor Built Environ. 2014, 23, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Miyazaki, Y. Interaction with indoor plants may reduce psychological and physiological stress by suppressing autonomic nervous system activity in young adults: A randomized crossover study. J. Physiol. Anthr. 2015, 34, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Shin, D.C.; Kim, K.J.; Lim, Y.W. Evaluation of self-assessed ocular discomfort among students in classroom according to indoor plant intervention. HortTechnology 2016, 26, 386–393. [Google Scholar]

- Nejati, A.; Rodiek, S.; Shepley, M. Using visual simulation to evaluate restorative qualities of access to nature in hospital staff break areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.; Sun, M.; Fujii, E. Psycho-physiological responses to plant variegation as measured through eye movement, self-reported emotion and cerebral activity. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.H.; Raanaas, R.K.; Hägerhäll, C.M.; Johansson, M. Nature in the office: An environmental assessment study. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2017, 34, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd, N.V.D.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Seidell, J.C.; Maas, J. Greenery in the university environment: Students’ preferences and perceived restoration likelihood. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192429. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Li, S. Study on the relationship between green space around workplace and physical and mental health:IT professionals in Beijing as target population. Landsc. Archit. Health 2018, 34, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T. Restorative environments. In Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology; Spielberger, C., Ed.; Academic Press: San Deigo, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ittelson, W.H.; Proshansky, H.M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Winkel, G.H. An Introduction to Environmental Psychology; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Nurs. Stand. 2009, 24, 30.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP UK Critical Appraisal Checklists; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. 2013. Available online: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Han, K.T. Effects of Indoor Plants on the Physical Environment with Respect to Distance and Green Coverage Ratio. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.; Steemers, K. Living walls in indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innenraumbegrünungsrichtlinien. 2011. Available online: https://shop.fll.de/de/bauwerksbegruenung/innenraumbegruenungsrichtlinien-2011.html (accessed on 1 August 2019).

| Source | Population | Interventions | Exposure Time | Distance to Plants | Room Size | Climate | Study Design | Psychological Perceptions | Outcomes | Publication Languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell, 1979 [21] | 251 US college students | 16 slides of a faculty office with or without four plants | Experiment | Emotion | Slides with plants produced higher level of comfort and were more welcoming to visitors than those without. | English | ||||

| Lohr, Pearson-Mims, and Goodwin, 1996 [22] | 96 US adults | Presence of 17 pots of plants in an indoor space | 13.5 × 7.3 × 2.6 m | 27 °C, 38% humidity, 420 lux | Field experiment | Cognition | Participants exhibited higher concentrations in an environment with the plants. | English | ||

| Fjeld, Veiersted, Sandvik, Riise, and Levy, 1998 [23] | 51 Norwegian office workers | 13 plants and a pot with five plants | Two spring periods of 3 months | 10 m2 | 22–24 °C | Field experiment | Health | The percentages by which the score sum of negative reactions decreased were observed: Discomfort symptoms (23%); complaints for coughing (37%); complaints for fatigue (30%); and levels of dry and hoarse throat as well as dry and itchy facial skin (23%). | English | |

| Larsen, Adams, Deal, Kweon, and Tyler, 1998 [17] | 81 US adults | A room with 22 pots of plants occupying 17.88% of the space, a room with 10 pots of plants occupying 7.16% of the space, and a room without plants | 20–30 min | 12 m2 | Experiment | Emotion | The room with 22 pots of plants was the most attractive. | English | ||

| Adachi, Rohde, and Kendle, 2000 [24] | 58 adults | The presence of 3 flower pot arrangements and 5 pots of foliage plants while watching videos | Experiment | Emotion | Videos were perceived as more attractive with the presence of flower pot arrangements than were the videos watched without the presence of flower pot arrangements | English | ||||

| Fjeld, 2000 [25] | Study 1: 51 Norwegian office workers Study 2: 48 X-ray department staff of a Norwegian hospital Study 3: 120 Norwegian junior high school students | Study 1: Presence of 13 pots of foliage plants in an office Study 2: Presence of pots of 23 foliage plants and a full-spectrum fluorescent lamp in an office Study 3: Presence of plants and a full-spectrum fluorescent lamp in a classroom | Study 1: Two spring periods of 3 months Study 2: 4 months Study 3: 12 months | Study 1: 10 m2 Study 2: 80 m2 | Study 3: 700–800 lux | Study 1: Field experiment Study 2: Field quasi-experiment Study 3: Field quasi-experiment | Health | Study 1: The score of health complaints among employees was significantly lower when the foliage plants were present than when they were absent. Study 2: The score of health complaints among employees decreased by 25% with fewer instances of fatigue, sleepiness, headache, dry and hoarse throat, and dry and itchy hands when the foliage plants were present than when they were not. Study 3: Health complaints among students decreased by 21% with fewer occasions of headache, dry and itchy eyes, and dry and hoarse throat in the classroom displaying plants than in the classroom without plants. | English | |

| Lohr and Pearson-Mims, 2000 [26] | 198 US adults | Presence of 5 pots of plants in a room where a pain-tolerance test involving participants submerging their hands in ice water was performed | Approx. 17 min | 3.5 × 6 × 2.4 m | 23 °C, 34% humidity, 703 lux | Experiment | Emotion | Prior to the test, participants reported higher levels of feeling carefree and friendly in the room with plants than in rooms without plants. After the test, participants felt happier in the presence of plants than with the absence of plants. | English | |

| Kim and Mattson, 2002 [27] | 150 US college students | The presence of 9 red-flowering geraniums | 20 min | 1.8 m | 22.4 °C | Experiment | Emotion, cognition | Participants reported more positive emotions and greater concentration in the presence of plants than in the space without plants. | English | |

| Liu, Kim, and Mattson, 2003 [20] | 66 US college students | The presence of a 45 x 45 x 45-cm flower pot arrangement | 30 min | 21 °C, 10.6 μmol·m−2s−1 | Experiment | Emotion | Participants reported more positive emotions when a flower pot arrangement was placed in the experiment room than in the room without plants. | English | ||

| Park, Mattson, and Kim, 2004 [28] | 90 female US college students | The presence of 10 pots of plants or seven pots of flowering plants when a pain-tolerance test was performed, in which participants submerged their hands in ice water | 40 min | 3.9 × 2.3 × 2.7 m | 21.7 °C, 904 lux | Experiment | Health | Participants perceived lower levels of pain and discomfort in the presence of plants than in the absence of plants. | English | |

| Shibata and Suzuki, 2004 [29] | 90 Japanese college students | A room with a 150-cm-tall plant, a magazine rack, or nothing placed 2.5 m in front of the participant | 15 min | Approx. 2.9 m | 2.78 × 5.81 × 2.35 m | Experiment | Emotion | Participants in the presence of plants reported more peaceful moods than when in the presence of the other two objects. | English | |

| Khan, Younis, Riaz, and Abbas, 2005 [30] | 250 faculty members and students from a university in Pakistan | The presence of indoor plants | Survey | Emotion, cognition | Indoor plants increased the pleasantness of the indoor landscapes; 76.8% of participants believed that indoor plants were helpful for improving academic performance. | English | ||||

| Bringslimark, Hartig, and Patil, 2007 [31] | 385 Norwegian employees | The presence of plants at several positions in a workplace | Survey | Health, productivity | The number of plants near work desks was correlated with health and productivity. | English | ||||

| Dijkstra, Pieterse, and Pruyn, 2008 [32] | 77 Dutch college students | Slides of a ward with and without 2 pots of plants | Experiment | Emotion | The slide of the ward with plants was perceived as more attractive than was the one without. Such attractiveness led to stress relief and physical and mental restoration. | English | ||||

| Dravigne, Waliczek, Lineberger, and Zajicek, 2008 [2] | 449 US office workers | The presence of plants | Survey | Emotion | People staying in the room with plants showed higher job satisfaction and higher quality of life than those in the room without plants. | English | ||||

| Park and Mattson, 2008 [33] | 90 patients receiving surgery | The presence of 12 pots of flowering plants in a ward | Field experiment | Emotion | Compared with patients staying in a plant-free ward, patients staying in the ward with plants exhibited lower anxiety and fatigue and greater satisfaction, relaxation, comfort, and warmth. | English | ||||

| Park, Song, Kim, Yamane, and Son, 2008 [34] | 23 South Korean female high school students | The presence of plants in a classroom | 15 weeks | Field quasi-experiment | Emotion | The presence of plants significantly reduced students’ stress. | English | |||

| Han, 2009 [35] | 76 Taiwanese junior high school students | The presence of plants (6 pots of plants 135 × 80 cm in height and width, with a green coverage of 6% in the room) | 12 weeks | Field quasi-experiment | Emotion | Students in the room with plants presented immediately stronger preferences, comfort, and friendliness than their control group counterparts. | English | |||

| Lim et al., 2009 [36] | 82 families | The presence of indoor plants | Survey | Health | Indoor plants and ventilation helped relieve symptoms of sick building syndrome. | English | ||||

| Park and Mattson, 2009 [37] | 80 South Korean female patients receiving surgery | The presence of 12 pots of flowering plants in a ward | Field experiment | Health | Patients in the ward with plants had lower perceived pain than those in the ward without plants. | English | ||||

| Hung and Han, 2010 [38] | 36 Taiwanese junior high school students | Placing 9 pots of plants or colorful photos of 9 pots of plants at the front or back of a classroom | 18 weeks | Field experiment | Emotion, restoration | When plants were placed at the front of the classroom, participants had greater friendliness. Students in the classroom with plants immediately perceived greater wellbeing. Real plants are associated with greater restorative components as well as higher student preferences, comfort, friendliness, perceived wellbeing and restoration than did the pictures. Sitting near a plant could immediately increase attractiveness. Levels of perceived preferences, comfort, wellbeing, restoration, and restorative components increased with the duration that plants were placed in the classroom. | Chinese | |||

| Kim et al., 2010 [39] | 82 residents of a newly built apartment in South Korea | The presence of plants in residences | Survey | Health | The presence of indoor plants and indoor ventilation created benefits for mental health and relieved symptoms of sick building syndrome. | English | ||||

| Raanaas, Patil, and Hartig, 2010 [40] | 282 Norwegian patients with heart or lung diseases | The presence of 28 pots of plants in the public area of a rehabilitation center | 4 weeks | Field quasi-experiment | Emotion | Patients in the ward with plants had higher satisfaction, yet only patients with lung diseases perceived greater wellbeing. | English | |||

| Han and Hung, 2011 [41] | 35 Taiwanese junior high school students | Placing 9 pots of plants and colorful photos of 9 pots of plants at the front or back of a classroom | 18 weeks | Field experiment | Emotion, restoration | Indoor plants helped improve perceived wellbeing. Plants placed at the front of a classroom were more likely to alleviate anxiety than plants being placed at the back. Additionally, placing plants at the back increased the perceived wellbeing more effectively than did placing colorful plant photos at the same spot. Furthermore, students sitting near a real plant or plant photo perceived lower anxiety than their classmates sitting far away. | Chinese | |||

| Kim et al., 2011 [42] | 71 Korean office workers | The presence of 22 and 25 pots of plants in new and old office buildings, respectively | 10 months | New building: 105 m2 Old building: 135 m2 | Survey | Health | The plants and ventilation in the old building helped reduce symptoms of sick building syndrome. | English | ||

| Brengman, Willems, and Joye, 2012 [43] | 4293 Dutch consumers | The presence of plants in the picture of a store | Survey | Emotion | Placing plants in stores did not trigger excitement, but did trigger happiness and reduced stress derived from a complex store layout. | English | ||||

| Han and Hung, 2012 [44] | 36 Taiwanese junior high school students | Placing 34 pots of plants inside and outside a classroom (green coverage rate inside the classroom = 6.3%) | 18 weeks | Field experiment | Emotion, restoration | Students who cared for plants perceived decreased anxiety and increased wellbeing, compared with their counterparts who did not. Students sitting near a plant reported lower anxiety and perceived greater wellbeing and attractiveness of plants compared with those sitting farther away. | Chinese | |||

| Li et al., 2012a [45] | 30 Chinese college students | Presenting 5 photos of vegetation landscapes to participants | 2 min | 0.5 m | 7 × 4 × 3 m | 25 °C, 40% humidity | Experiment | Emotion | Purple and green plants more effectively reduced levels of anger, fatigue, and anxiety than red, yellow, and white plants. | English |

| Li et al., 2012b [46] | 30 Chinese college students | Presenting 12 photos of flowers to participants | 2 min | 0.5 m | 7 × 4 × 3 m | 25 °C, 40% humidity | Experiment | Emotion | Pink and white flowers alleviated negative emotions including anxiety, anger, and fatigue; red and yellow plants stimulated vitality. Participants viewing photos of different colors revealed significantly different anxiety levels, whereas such difference was nonsignificant regarding plant species. | English |

| Elsadek et al., 2013 [47] | 29 Japanese college students | Five Hedera helix L. of different colors | 5 min | 0.5 m | Experiment | Emotion | More women reported stronger preferences for white plants than did men; yellow plants helped increase positive emotions for both men and women, whereas red plants stimulated perceived warmth and luxury. | English | ||

| Kim et al., 2013 [48] | 115 Korean elementary school students | Presence of plants in classrooms at two newly built elementary schools | 95 days | 9 × 7.5 m | Quasi-experiment | Health | Indoor plants reduced symptoms of sick building syndrome. | English | ||

| Leng et al., 2013 [49] | 16 Chinese college students | Seven types of environment (a nonplant environment and six environments with different plants) | 5 min | 6 × 5 × 3.2 m | Experiment | Satisfaction | 75% of participants reported greater satisfaction with environments with plants than with a nonplant environment. The scent, color, leaf size, and number of plants were significantly correlated with satisfaction. | Chinese | ||

| Elsadek and Fujii, 2014 [50] | 28 Japanese college students | Three plants in different colors | 3 min | 1.5 m | 59.4 m2 | 23 °C, 55% humidity, 700 lux | Experiment | Emotion | Both men and women preferred the green Spathiphyllum wallisii, disliked the green–red Cordyline terminalis the most, and exhibited neutral preferences for the white Aglaonema pictum. | English |

| Jang, Kim, Kim, and Pak, 2014 [51] | 30 Korean college students | Five plants of different colors | 5 min | 1 m | 7 × 4.5 × 2.8 m | 25 °C, 70% humidity, 700 lux | Experiment | Emotion | Green plants, green plants with white flowers, and green plants with yellow flowers generated feelings of comfort and pleasantness, whereas green plants with pink flowers and green plants with red flowers stimulated active brain functions and anxiety. | English |

| Mangone et al., 2014 [52] | 67 Dutch office workers | The presence of plants in offices | 4 months | 10,000 m2 | Quasi-experiment | Thermal comfort | Plant placement significantly affected perceived thermal comfort. | English | ||

| Nieuwenhuis, Knight, Postmes, and Haslam, 2014 [53] | Study 1: 67 UK office workers Study 2: 81 Dutch office workers Study 3: 33 UK office workers | Study 1: Presence of plants Study 2: Presence of plants Study 3: Presence of plants | Study 1: 3 weeks Study 2: 2 weeks, 3.5 months | Study 1: 4875 m2 Study 2: 360 m2 | Study 1: Field experiment Study 2: Quasi-experiment Study 3: Field experiment | Study 1: Emotion, cognition Study 2: Emotion, cognition Study 3: Cognition | Study 1: Indoor plants helped improve concentration, air quality, and productivity. Study 2: Indoor plants helped improve satisfaction and air quality; these levels were maintained for 3.5 months. The adopted plants also helped reduce disengagement. Study 3: Indoor plants helped improve the spatial quality of an office. | English | ||

| Qin, Sun, Zhou, Leng, and Lian, 2014 [54] | 16 Chinese college students | Presence of 3 plants with different colors, scents, and sizes. | 10–15 min | Experiment | Emotion | Greater satisfaction was perceived in the presence of plants than in the absence of plants. Small green plants with a slight scent yielded the highest satisfaction levels. | English | |||

| Lee, Lee, Park, and Miyazaki, 2015 [55] | 24 South Korean male adults | A task involving transplanting an indoor plant and a computer task | 15 min | 20.8 °C, 57.7% humidity, 1365.5 lux | Experiment | Emotion | Participants felt comfortable, soothed, and natural after completing the transplant task. | English | ||

| Kim et al., 2016 [56] | 115 South Korean elementary school students | The presence of plants in classrooms at two newly built elementary school | 113 days | 7.7 × 9 m | 15–25°C | Quasi-experiment | Health | Indoor plants helped reduce the frequency and alleviate symptoms associated with eye grittiness and other ocular discomfort. | English | |

| Nejati, Rodiek, and Shepley, 2016 [57] | 958 US nurses | 10 photos of indoor spaces | Survey | Restoration | Photos with plants were more conducive to relieving stress and restoring energy than non-plant photos. | English | ||||

| Elsadek, Sun, and Fujii, 2017 [58] | 30 Egyptian male adult students | Five Hedera helix L. of different colors | 3 min | 0.5 m | 59.4 m2 | 21 °C, 55% humidity | Experiment | Emotion | Yellowish-green and fresh green helped enhance comfort and calmness; red and dark green increased energy; and white increased negative emotions. | English |

| Evensen et al., 2017 [59] | Study 1: 56 Norwegian college students Study 2: 46 Norwegian college students | Study 1: An office with plants and inanimate objects, an office with only inanimate objects and an office without any plants or inanimate objects Study 2: Three slides of the office used in study 1 | Study 1: 15 min Study 2: 25 min | 2.1 × 3.9 × 3.6 m | Experiment | Emotion | Participants perceived significantly greater pleasantness in the office with plants than in the other two offices. | English | ||

| Han, 2018 [7] | 35 Taiwanese junior high school students | The presence of 45 plants inside and outside a classroom (green coverage inside the classroom = 3.1%) | 18 weeks | Field experiment | Emotion, restoration, knowledge | Participants who cared for plants had lower stress than those who did not. Interactions with plants helped students restore concentration. Plant-related knowledge increased with time spent caring for plants. | English | |||

| van den Bogerd et al., 2018 [60] | 722 Dutch college students | Six indoor photos and 4 outdoor photos | Survey | Emotion | Students preferred the picture of an indoor environment containing natural-landscape posters, green walls, and indoor plants. | English | ||||

| Yao et al., 2018 [61] | 351 employees working in the Chinese information technology industry | Changing the number of plants placed inside an office and those on office desks | Survey | Emotion, health | The number of indoor plants slightly affected participants’ health; the number of indoor plants in an office was significantly and negatively correlated with participants’ stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and somatic symptom disorders. | Chinese |

| Publication Year | Publication Languages | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | English | |||||

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| 1979–1988 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.22 |

| 1989–1998 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7.5 | 3 | 6.67 |

| 1999–2008 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 32.5 | 13 | 28.89 |

| 2009–2018 | 5 | 100 | 23 | 57.5 | 28 | 62.22 |

| Total | 5 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 45 | 100 |

| Study Design | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 19 | 38.78 |

| Field experimental | 11 | 22.45 |

| Survey | 10 | 20.41 |

| Field quasi-experimental | 5 | 10.20 |

| Quasi-experimental | 4 | 8.16 |

| Total | 49 | 100 |

| Psychological Perceptions | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Emotion | 31 | 56.36 |

| Health | 11 | 20.00 |

| Restoration | 5 | 9.09 |

| Cognition | 4 | 7.27 |

| Knowledge | 1 | 1.82 |

| Thermal comfort | 1 | 1.82 |

| Satisfaction | 1 | 1.82 |

| Productivity | 1 | 1.82 |

| Total | 55 | 100 |

| Participant Nationalities | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| American | 9 | 20.45 |

| South Korean | 7 | 15.91 |

| Norwegian | 5 | 11.36 |

| Dutch | 5 | 11.36 |

| Taiwanese | 5 | 11.36 |

| Chinese | 5 | 11.36 |

| British | 3 | 6.82 |

| Japanese | 3 | 6.82 |

| Pakistani | 1 | 2.27 |

| Egyptian | 1 | 2.27 |

| Total | 44 | 100 |

| Quality Indicators | Campbell, 1979 [21] | Lohr et al., 1996 [22] | Fjeld et al., 1998 [23] | Larsen et al., 1998 [17] | Adachi et al., 2000 [24] | Fjeld, 2000 [25] | Lohr and Pearson-Mims, 2000 [26] | Kim and Mattson, 2002 [27] | Liu et al., 2003 [20] | |

| Study Design | Power calculation reported | No | No | No | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria reported | No | No | Yes | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No | No | No | No | |

| Individual level allocation | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Random allocation to groups/Condition/order | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Study 1: Yes Study 2: No Study 3: No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Randomization procedure appropriate | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Study 1: Yes Study 2: No Study 3: No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | |

| Confounders | Groups similar (sociodemographic) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partial | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. Study 3: Un. | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Group balanced at baseline | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. Study 3: Un. | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Participants blind to research question | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | |

| Intervention integrity | Clear description of intervention and control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Consistency of intervention (within and between groups) | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Pa. Study 2: Yes Study 3: No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Data collection methods | Outcome assessors blind to group allocation | Yes | No | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Baseline measures taken before the intervention | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Unclear Study 2: Unclear Study 3: Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Consistency of data collection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Partial Study 2: Partial Study 3: Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Analyses | All outcomes reported (means and SD/SE) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No | No | No | No |

| All participants accounted for (i.e., losses/ exclusions) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| ITT analysis conducted (all data included after allocation) | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Unclear Study 2: Unclear Study 3: Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Individual level analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Statistical analysis methods appropriate for study design | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| External validity | Sample representative of target population | No | No | No | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No | No | No | No |

| Overall quality score | Total number of points (out of possible 38) | 18 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 17 | Study 1: 14 Study 2: 11 Study 3: 9 | 18 | 20 | 22 |

| Quality rating as percent | 47.4 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 57.9 | 44.7 | Study 1: 36.8 Study 2: 28.9 Study 3: 23.7 | 47.4 | 52.6 | 57.9 | |

| Responded to query about “uncertain” ratings | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | No | No | NA | Yes | |

| Quality Indicators | Park et al., 2004 [28] | Shibata and Suzuki, 2004 [29] | Khan et al., 2005 [30] | Bringslimark et al., 2007 [31] | Dijkstra et al., 2008 [32] | Dravigne et al., 2008 [2] | Park and Mattson, 2008 [33] | Park et al., 2008 [34] | Han, 2009 [35] | |

| Study Design | Power calculation reported | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion/ exclusion criteria reported | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Individual level allocation | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No | No | |

| Random allocation to groups/ Condition/ order | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No | No | |

| Randomization procedure appropriate | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No | No | |

| Confounders | Groups similar (sociodemographic) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Partical | Unclear | Unclear | Partial |

| Group balanced at baseline | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Participants blind to research question | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | |

| Intervention integrity | Clear description of intervention and control | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Consistency of intervention (within and between groups) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Data collection methods | Outcome assessors blind to group allocation | Unclear | No | NA | NA | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No |

| Baseline measures taken before the intervention | No | Yes | Unclear | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Consistency of data collection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Analyses | All outcomes reported (means and SD/SE) | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| All participants accounted for (i.e., losses/ exclusions) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| ITT analysis conducted (all data included after allocation) | Unclear | Unclear | NA | NA | Unclear | NA | Unclear | Unclear | No | |

| Individual level analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ye | |

| Statistical analysis methods appropriate for study design | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| External validity | Sample representative of target population | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Overall quality score | Total number of points (out of possible 38) | 20 | 24 | 4 | 8 | 18 | 11 | 22 | 12 | 19 |

| Quality rating as percent | 52.6 | 63.2 | 10.5 | 21.1 | 47.4 | 28.9 | 57.9 | 31.6 | 50.0 | |

| Responded to query about “uncertain” ratings | NA | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |||

| Quality Indicators | Lim et al., 2009 [36] | Park and Mattson, 2009 [37] | Hung and Han, 2010 [38] | Kim et al., 2010 [39] | Raanaas et al., 2010 [40] | Han and Hung, 2011 [41] | Kim et al., 2011 [42] | Brengman et al., 2012 [43] | Han and Hung, 2012 [44] | |

| Study Design | Power calculation reported | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria reported | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Individual level allocation | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Random allocation to groups/ Condition/order | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Randomization procedure appropriate | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Confounders | Groups similar (sociodemographic) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| Group balanced at baseline | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Participants blind to research question | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | |

| Intervention integrity | Clear description of intervention and control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Consistency of intervention (within and between groups) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Data collection methods | Outcome assessors blind to group allocation | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | No |

| Baseline measures taken before the intervention | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Consistency of data collection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Analyses | All outcomes reported (means and SD/SE) | No | No | Partial | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| All participants accounted for (i.e., losses/ exclusions) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| ITT analysis conducted (all data included after allocation) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | |

| Individual level analysis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Statistical analysis methods appropriate for study design | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| External validity | Sample representative of target population | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Overall quality score | Total number of points (out of possible 38) | 6 | 22 | 21 | 14 | 13 | 22 | 10 | 22 | 24 |

| Quality rating as percent | 15.8 | 57.9 | 55.3 | 36.8 | 34.2 | 57.9 | 26.3 | 57.9 | 63.2 | |

| Responded to query about “uncertain” ratings | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | ||||

| Quality Indicators | Li et al., 2012a [45] | Li et al., 2012b [46] | Elsadek et al., 2013 [47] | Kim et al., 2013 [48] | Leng et al., 2013 [49] | Elsadek and Fujii, 2014 [50] | Jang et al., 2014 [51] | Mangone et al., 2014 [52] | Nieuwenhuis et al., 2014 [53] | |

| Study Design | Power calculation reported | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No |

| Inclusion/ exclusion criteria reported | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Study 1: Yes Study 2: No Study 3: No | |

| Individual level allocation | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No | |

| Random allocation to groups/ Condition/order | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Study 1: Yes Study 2: No Study 3: Yes | |

| Randomization procedure appropriate | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | Study 1: Yes Study 2: No Study 3: Yes | |

| Confounders | Groups similar (sociodemographic) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Pa. Study 2: Yes Study 3: Un |

| Group balanced at baseline | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Unclear Study 2: Unclear Study 3: Unclear | |

| Participants blind to research question | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | |

| Intervention integrity | Clear description of intervention and control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes |

| Consistency of intervention (within and between groups) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: No Study 2: Yes Study 3: No | |

| Data collection methods | Outcome assessors blind to group allocation | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No |

| Baseline measures taken before the intervention | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: No | |

| Consistency of data collection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | |

| Analyses | All outcomes reported (means and SD/SE) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: No |

| All participants accounted for (i.e., losses/ exclusions) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: Yes | |

| ITT analysis conducted (all data included after allocation) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Un Study 2: Un Study 3: Un | |

| Individual level analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | |

| Statistical analysis methods appropriate for study design | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes Study 3: Yes | |

| External validity | Sample representative of target population | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No Study 3: No |

| Overall quality score | Total number of points (out of possible 38) | 24 | 24 | 22 | 12 | 18 | 20 | 20 | 16 | Study 1: 21 Study 2: 18 Study 3: 16 |

| Quality rating as percent | 63.2 | 63.2 | 57.9 | 31.6 | 47.4 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 42.1 | Study 1: 55.3 Study 2: 47.4 Study 3: 42.1 | |

| Responded to query about “uncertain” ratings | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Quality Indicators | Qin et al., 2014 [54] | Lee et al., 2015 [55] | Kim et al., 2016 [56] | Nejati et al., 2016 [57] | Elsadek et al., 2017 [58] | Evensen et al., 2017 [59] | Han, 2018 [7] | van den Bogerd et al., 2018 [60] | Yao et al., 2018 [61] | |

| Study Design | Power calculation reported | Yes | No | No | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion/ exclusion criteria reported | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Study 1: No Study 2: No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Individual level allocation | No | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | No | Yes | NA | |

| Random allocation to groups/ Condition/ order | Unclear | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | |

| Randomization procedure appropriate | Unclear | Yes | No | NA | Unclear | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. | Yes | Unclear | NA | |

| Confounders | Groups similar (sociodemographic) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. | Yes | Unclear | Unclear |

| Group balanced at baseline | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Participants blind to research question | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Intervention integrity | Clear description of intervention and control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Consistency of intervention (within and between groups) | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Partial | No | No | |

| Data collection methods | Outcome assessors blind to group allocation | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. | No | Unclear | Unclear |

| Baseline measures taken before the intervention | No | No | Yes | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No | Yes | No | No | |

| Consistency of data collection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Analyses | All outcomes reported (means and SD/SE) | No | No | No | Yes | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No | No | No | No |

| All participants accounted for (i.e., losses/ exclusions) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| ITT analysis conducted (all data included after allocation) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | NA | Unclear | Study 1: Un. Study 2: Un. | Unclear | No | No | |

| Individual level analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Statistical analysis methods appropriate for study design | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Study 1: Yes Study 2: Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| External validity | Sample representative of target population | No | No | No | No | No | Study 1: No Study 2: No | No | No | No |

| Overall quality score | Total number of points (out of possible 38) | 14 | 18 | 12 | 16 | 18 | Study 1: 16 Study 2: 18 | 23 | 12 | |

| Quality rating as percent | 36.8 | 47.4 | 31.6 | 42.1 | 47.4 | Study 1: 42.1 Study 2: 47.4 | 60.5 | 31.6 | ||

| Responded to query about “uncertain” ratings | Yes | NA | ||||||||

| Quality Indicators | Yes | Partial | No | Unclear | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | (%) | Frequency | (%) | Frequency | (%) | Frequency | (%) | |

| Power calculation reported | 2 | 4.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 48 | 96.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria reported | 16 | 32.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 34 | 68.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Individual level allocation | 24 | 53.33 | 0 | 0.00 | 21 | 46.67 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Random allocation to groups/Condition/order | 30 | 66.67 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 26.67 | 3 | 6.67 |

| Randomization procedure appropriate | 23 | 51.11 | 1 | 2.22 | 12 | 26.67 | 9 | 20.00 |

| Groups similar (sociodemographic) | 8 | 16.00 | 4 | 8.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 38 | 76.00 |

| Group balanced at baseline | 2 | 4.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 48 | 96.00 |

| Participants blind to research question | 22 | 44.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 26 | 52.00 |

| Clear description of intervention and control | 47 | 94.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 1 | 2.00 |

| Consistency of intervention (within and between groups) | 32 | 64.00 | 3 | 6.00 | 14 | 28.00 | 1 | 2.00 |

| Outcome assessors blind to group allocation | 3 | 6.25 | 0 | 0.00 | 13 | 27.08 | 32 | 66.67 |

| Baseline measures taken before the intervention | 19 | 38.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 20 | 40.00 | 11 | 22.00 |

| Consistency of data collection | 44 | 88.00 | 4 | 8.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| All outcomes reported (means and SD/SE) | 12 | 24.00 | 1 | 2.00 | 37 | 74.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| All participants accounted for (i.e., losses/exclusions) | 38 | 76.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 24.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| ITT analysis conducted (all data included after allocation) | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 13.04 | 40 | 86.96 |

| Individual level analysis | 49 | 98.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Statistical analysis methods appropriate for study design | 47 | 94.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 1 | 2.00 |

| Sample representative of target population | 1 | 2.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 49 | 98.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, K.-T.; Ruan, L.-W. Effects of Indoor Plants on Self-Reported Perceptions: A Systemic Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164506

Han K-T, Ruan L-W. Effects of Indoor Plants on Self-Reported Perceptions: A Systemic Review. Sustainability. 2019; 11(16):4506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164506

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Ke-Tsung, and Li-Wen Ruan. 2019. "Effects of Indoor Plants on Self-Reported Perceptions: A Systemic Review" Sustainability 11, no. 16: 4506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164506

APA StyleHan, K.-T., & Ruan, L.-W. (2019). Effects of Indoor Plants on Self-Reported Perceptions: A Systemic Review. Sustainability, 11(16), 4506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164506