Abstract

Over the past forty years, income growth for the middle and lower classes has stagnated, while the economy (and with it, economic inequality) has grown significantly. Early automation, the decline of labor unions, changes in corporate taxation, the financialization and globalization of the economy, deindustrialization in the U.S. and many OECD countries, and trade have contributed to these trends. However, the transformative roles of more recent automation and digital technologies/artificial intelligence (AI) are now considered by many as additional and potentially more potent forces undermining the ability of workers to maintain their foothold in the economy. These drivers of change are intensifying the extent to which advancing technology imbedded in increasingly productive real capital is driving productivity. To compound the problem, many solutions presented by industrialized nations to environmental problems rely on hyper-efficient technologies, which if fully implemented, could further advance the displacement of well-paid job opportunities for many. While there are numerous ways to address economic inequality, there is growing interest in using some form of universal basic income (UBI) to enhance income and provide economic stability. However, these approaches rarely consider the potential environmental impact from the likely increase in aggregate demand for goods and services or consider ways to focus this demand on more sustainable forms of consumption. Based on the premise that the problems of income distribution and environmental sustainability must be addressed in an integrated and holistic way, this paper considers how a range of approaches to financing a UBI system, and a complementary market solution based on an ownership-broadening approach to inclusive capitalism, might advance or undermine strategies to improve environmental sustainability.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Inequality Challenge

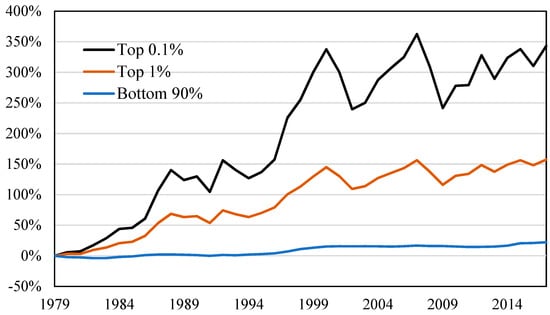

Until the 1980s, growth in U.S. labor productivity, private employment, median family income, and real GDP per capita grew in tandem (Figure 1) [1]. Since then, growth in private employment and median family income has lagged behind economic growth, and during the 2000s was largely stagnant. These trends reveal that compared to the rest of the population, the top 10 percent and, especially, the top 1 and 0.1 percent of the U.S. population measured by real annual earnings, have experienced by far the greatest financial gains (Figure 2). Since the 1970s, when compared with the 90th percentile, median family wealth in the U.S. has been flat, revealing that the U.S. middle class, and especially minority/disadvantaged populations, are no longer benefiting from gains in labor productivity and economic growth [2]. Further, since 2000, wages as a percentage of GDP have fallen sharply (dropping below 60% for the first time around 2005), while the share of GDP going to corporate profits has been increasing [1]. One outcome from these trends is that younger generations are finding it more difficult to accumulate wealth (Figure 3) [3].

Figure 1.

Key economic, productivity, and private employment trends, 1953–2018. Note: Index 1953 = 100. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Adapted and updated from Reference [1].

Figure 2.

Cumulative percent change in real annual earnings (by earnings group), 1979–2017. Note: Index 1979 = 0%. Sources: Adapted from Reference [4] and U.S. Social Security Administration wage statistics.

Figure 3.

Deviation of median wealth from predicted value. Note: Deviation of 2016 wealth from predicted values based on life cycle wealth trajectories. Source: Adapted from Reference [3].

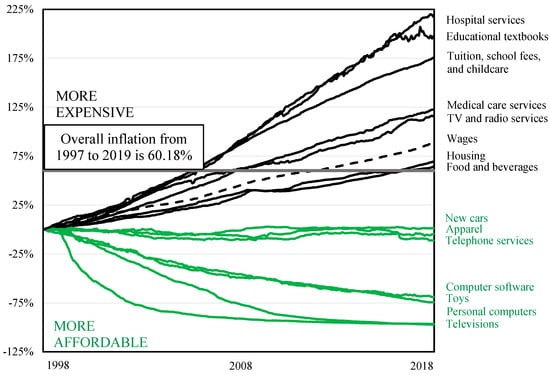

If these trends are considered alongside changes in the cost of living (Figure 4), it can be seen that growing healthcare and education expenses are most likely to impact the young and poor [5,6,7]. In contrast, the reduction in the price of tradeable goods and services such as communication has likely somewhat softened the impact of stagnant wages for the majority of workers.

Figure 4.

Price changes 1997 to 2018. Note: The black lines indicate prices (of non-tradeable goods and services) that are typically not subject to market forces. The green lines indicate the prices (of tradable goods and services) that are subject to competition/market forces. The dotted line represents wages. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Adapted and updated from Reference [13].

Given the above, a critical question is “why have workers (through wages) failed to maintain their share of GDP?” Earlier automation, the decline of labor unions, changes in corporate taxation, the financialization and globalization of the economy, deindustrialization in the U.S. and many OECD countries, and trade have surely played a role [8,9]. However, the transformative roles of more recent automation and digital technologies/artificial intelligence (AI) are now considered by many as the emerging forces undermining the ability of workers to maintain their foothold in the economy [8,10,11]. Automation is likely to impact 1.2 billion jobs globally (representing $14.6 trillion in wages) and 60.6 million jobs in the United States (equivalent to $2.3 trillion in wages) [12]. Jobs with highly predictable physical work are more likely to be automated with existing technological capabilities. Some of these jobs include, but are not limited to, food preparation and serving tasks in accommodation and food service businesses, aircraft assemblers, first-line supervisors in the resource extraction industry, and transportation and warehousing jobs [12]. The disruption caused by AI and automation technologies is likely to only continue to increase as their capabilities improve and costs decline.

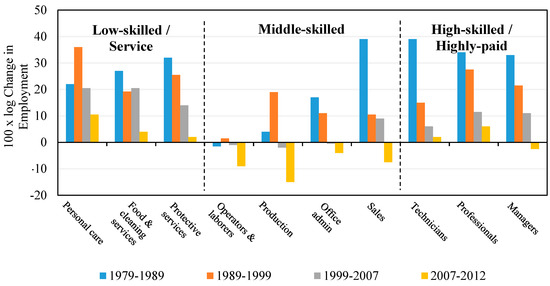

These drivers of change are intensifying the extent to which increasingly productive real capital is driving productivity and simultaneously hollowing out the middle class (Figure 5) [14]. The polarization of the workforce is increasing the skills needed to engage in the high-skilled/high-earning jobs, making them unattainable for many. From 1980 to 2015, the number of workers in jobs that require average or above-average education, training, and experience increased by 68 percent, whereas employment in lower-skill jobs had a weaker growth of 31 percent [15]. These lower-skill jobs do not provide the same income status that middle-income jobs used to provide and have a higher likelihood of becoming automated in the future [16]. Female workers may also bear the brunt of technological displacement, worsening the gender gap [17,18]. As middle-income jobs hollow out, the majority of workers find themselves searching for employment in the service sector. In fact, over 90 percent of net employment growth in the U.S. from 2005 and 2015 appears to have occurred in the service sector (in independent freelance/contract work, temporary work, etc.), with conventional full-time jobs in decline [19]. The polarization of the workforce is not just a U.S. phenomenon; it is also occurring in the majority of European countries [14,16]. In the OECD, over the past three decades an average of 1% of the population each decade has ceased to be middle income—defined as “households earning between 75% and 200% of the median national income” [16] (p. 13)—with one third moving into the upper-income category and two thirds moving into the lower income category.

Figure 5.

Change in employment by major occupational category, 1979–2012. Note: This figure plots percentage point changes in employment (more precisely, the figure plots 100 times log changes in employment, which is close to equivalent to percentage points for small changes) by decade for the years 1979–2012 for ten major occupational groups encompassing all of U.S. nonagricultural employment. Agricultural occupations comprise no more than 2.2 percent of employment in this time interval, so this omission has a negligible effect. Source: Adapted from Reference [14].

The trends above paint a challenging picture that is increasingly apparent to growing numbers of people, but it is not new. In the mid-1960s, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. identified the problem through his work on civil rights and the Poor People’s campaign. In his final book, “Where Do We Go From Here? Community or Chaos”, Dr. King, Jr. made the following statement:

“Automation is imperceptibly but inexorably producing dislocations, skimming off unskilled labor from the industrial force. The displaced are flowing into proliferating service occupations. These enterprises are traditionally unorganized and provide low wage scales with longer hours”.[20] (p. 149)

Given the challenges presented above, two critical questions are (1) how to shape the economy so that it directly addresses current trends in income and wealth inequality and works for everyone [21], and (2) how to accomplish this in a way that is environmentally sustainable [22].

1.2. The Environmental Challenge

A corollary concern to inequality is the environmental challenge. There are four general areas of environmental concern that have emerged over the past fifty years [8]: (1) ecosystem integrity and the loss of biodiversity; (2) resource depletion; (3) toxic pollution; and (4) climate change.

Concerns about the disruption of ecosystems, the loss of biological diversity, and the indirect effects these have on human health and well-being were initially raised in the early 1960s, when industrial processes and the use of pesticides were revealed to have led to environmental degradation and a loss of wildlife [23]. Three decades later, public concern began to focus on endocrine disrupters that affect reproductive health in all species [24,25]. More recent concerns have been raised about the impacts of the loss of biodiversity on mental health, nutrition, and increased exposure to infectious diseases [26]. While significant technological progress has been made in improving industrial and agricultural practices, the negative impacts of these sectors still present a problem [27].

The second environmental concern relates to the world’s finite resources and energy supplies and asks whether there are sufficient resources to provide continuing economic growth—i.e., are there limits to growth [28,29,30,31]? A connected concern is what the environmental impact will be from using a significant proportion of the existing resources.

The third concern is toxic pollution that directly adversely affects human health and the health of other species [24,27,32,33,34,35,36,37]. As scientists began to understand how ecosystems, humans, and other organisms were affected by industrial and agricultural processes, the issue of how toxic chemicals interact with biological systems gained prominence. In the same way, the understanding of how communities of color in the U.S. suffer as a result of the disproportionate exposure to toxic pollutants that they themselves do not generate is gaining greater recognition [38,39,40,41].

The final, more recent, concern is that greenhouse gases from anthropocentric (human-driven) sources are leading to a disruption of the global climate [42]. Scientists predict (with high confidence) that relative to 1850–1900, these gases will cause the globally averaged surface air temperature to increase by at least 1.5 °C by the end of the 21st century (2081–2100) [42]. The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement (COP21) focuses on limiting a rise in global average temperature “to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels,” with an aspirational target of limiting the increase to 1.5 °C [43] (p. 3). Achieving the target of 1.5 °C of warming above pre-industrial levels will be extremely difficult without massive and targeted investment in low-carbon technology, and even if the 1.5 °C target is achieved, low-lying regions and the poor/vulnerable will still be adversely impacted [44]. At the other end of the continuum where predictions put the warming of the planet around 4 °C by the end of the century [45], the costs of doing little or nothing (i.e., business as usual) are catastrophic [46].

The first, third, and fourth environmental concerns are connected with the unintended effects of growing human production and consumption systems, while the second deals with increasing shortages of resources needed to fuel these systems.

Today, the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a comprehensive statement on the tenets of sustainable development. The SDGs also continue to advance a technologically optimistic and growth-oriented approach to development that has its roots in the Brundtland formulation of sustainable development. For example, SDG 9 calls for “inclusive and sustainable industrialization” supported by “innovation,” and SDG 8 for “sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all.” The challenge is that an innovation-fueled “green” growth agenda (SDG 9) is unlikely to realize the latter employment goals if technology continues to displace routine (physical and cognitive) tasks [10,47,48,49]. Thus, while environmental improvements may occur, the goal of addressing inequality via “full and productive employment” is unlikely to be achieved.

1.3. Moving Beyond Green Growth

While the notion of “green growth” [50] is an important step beyond the current growth paradigm, going green is not enough to handle the income/wealth disparities that have been developing [48,49]. Further, there is no empirical evidence that green growth has, or will in the near future, decouple the economy from its environmental impacts [51], highlighting the need for a fundamentally different approach to how we advance economic development and sustainability.

A more plausible outcome from innovation-fueled “green” growth might be that as production becomes more capital (i.e., technology) intensive, the ability to distribute wealth via wages will decline, revealing an urgent need for capital-based mechanisms for income/wealth distribution. Expressed in more general terms, as production becomes more capital intensive, there is an urgent need for income distribution to also become more capital intensive. This framing has important implications for the financing of a UBI designed to address income inequality. Further, as the comparative analysis in this paper reveals, while some UBI approaches do incorporate environmental concerns; many do not. Thus, selecting or developing a UBI approach that combines the earnings of capital ownership with a robust environmental protection regime, presents a unique opportunity to move beyond the green growth agenda.

1.4. The EKC Hypothesis

Given the core argument of this paper that any strategy to advance a UBI must be integrated with mechanisms to protect the environment, there may be some who might respond that the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis means the focus need only be on increasing income/wealth. The EKC hypothesis postulates that the relationship between a specific environmental pollutant (such as sulfur dioxide) and per capita income follows an inverted-U shape. This relationship implies that as a nation’s GDP per capita increases, environmental degradation will first increase up to a turning point that varies by pollutant [52,53,54], after which it will begin to fall. The EKC hypothesis challenges the need to consider UBIs from an environmental perspective, because if the relationship holds, the increased income could enable people to demand and pay for environmental improvements.

However, the EKC hypothesis is a somewhat academic idea that on balance is not supported by the empirical evidence [55,56,57,58,59]. While EKCs have been found in relation to local air pollutants, they do not hold for long-lived measures such as carbon dioxide (CO2), municipal waste, and persistent toxic chemicals, which increase monotonically with per capita income [60,61,62,63]. Studies focusing on the EKC hypothesis also do not consider the total impact of economic growth on the environment and whether this may (in some cases) be irreversible [61].

If a UBI is implemented without any consideration of the environmental impacts caused by a surge in consumption from a sudden increase in aggregate demand, it is highly likely that environmental problems will worsen and that—without an innovative regulatory regime that protects critical ecological systems and promotes disruptive technological change [8]—these may not decline over time. A similar concern was raised in the context of adopting a four-day workweek to allegedly reduce consumption [64,65].

The following section reviews a broad range of approaches to financing a UBI and highlights how these approaches (1) frame the driving forces of growing income/wealth inequality and (2) consider the impact that the proposed UBI might have on the environment.

2. Strategies to Provide a Universal Basic Income (UBI)

In response to growing trends in inequality across the world, the idea of a universal basic income (UBI) is increasingly gaining traction not only in academic circles, but also in policy arenas. Indeed, “[t]he idea of assured [guaranteed/basic] income is in the policy and political air” [9] (p. 10). Those advocating for a UBI tend to do so on the grounds of social justice, individual liberty, and financial security [66,67]. Some advocates argue that policies that more broadly distribute or redistribute income will promote fuller employment and per-capita growth [68,69].

Those opposing a UBI tend to raise questions about its affordability, the need to raise taxes in ways likely to suppress growth-enhancing investment and employment, and the possibility that a UBI would reduce people’s incentive to work. Indeed, labor work plays a role not only in financial stability, but also in psychological well-being and social integration; and a UBI could constitute, in some cases, a disincentive to find a job. This debate has been going for some time in EU countries, where there are typically systems in place covering shortfalls in earning capacity, with the state providing allowances for underprivileged households and/or unemployment compensations. A “solution” has consisted of making unemployment benefits temporary and dependent on the amount of days previously worked, so that beneficiaries have incentives to find a job. However, this arrangement is proving insufficient in cases (increasingly frequent) of the longtime unemployed who often find themselves unable to secure a job, lacking marketable skills, and without unemployment benefits.

Although the approaches may vary, there are only five ways to legitimately increase the funds available to people to cover their consumer needs and wants: (1) labor (wages); (2) capital (dividends, interest, and rent); (3) government redistribution of income and capital; (4) private charity; and (5) consumer debt. Because consumer debt without the future repayment ability is unsustainable, private charity has proven systemically inadequate, and capital acquisition based on mainstream market principles has produced an increasing concentration (rather than a broadening) of capital ownership, most approaches to enhancing income for poor and middle class people are based on increasing wages and/or government redistribution of income or capital.

As will be discussed below, there is an alternative approach to broadening capital ownership that is based on binary economics. This approach maintains that it is the increasing productiveness of capital enhanced by technological advance (not labor) that is doing an ever greater share of the work, creating more of the wealth, and is driving economic growth and inequality [70]. When understood through this lens, the mechanism of how a UBI is financed matters.

As automation and AI do an increasing share of work relative to labor, financing a UBI in a way that directly links income to the work being done, and wealth created, by capital is critical. When framed this way, people could receive an income from their labor and from the work that the capital they may own does for them. Thus, the understanding of work and its distributive consequences needs to be viewed not only as the work done by labor, but also the work increasingly done by capital. A key question raised by this approach is how people can acquire a capital ownership stake without using labor earnings (which for growing numbers of people are already insufficient to support their needs without being supplemented by growing consumer debt). A second and equally important question is how the ownership-broadening capital acquisition can be structured to advance sustainable, rather than destructive, production and consumption. These questions are addressed below and in Section 3.

A UBI could be provided through either a redistributive or distributive approach, or some combination of the two (as proposed in Section 3). The redistributive approach would finance a UBI by redistributing wealth through taxes on earned income/accumulated wealth. The distributive approach, would finance a UBI by profitable, credit-worthy enhanced growth prospects that can rationally be expected to result from a broader distribution of capital acquisition and future capital income. This approach would cause a broader future distribution, rather than a current redistribution, of wealth and income.

Regardless of the rationale for providing a basic income, the idea is now attracting support from many quarters [71]. This interest has prompted the launch of a number of basic income pilot projects around the world (Box 1). While these pilots seem structured to help deepen knowledge regarding the impact of different forms of a UBI on the recipients of the income, a number of proposals exist for implementing a basic income for all citizens/residents of a country/region. Table 1 provides a summary of several economy-wide approaches to providing a UBI (or guaranteed employment) and highlights their financing mechanism, whether the approach has an employment requirement, the income received (if known) and by whom, and whether a connection exists between the approach and sustainable development. A more detailed description of each program is provided in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Summary of strategies to address income inequality.

Box 1. Examples of basic income pilot projects.

Finland: Finland ran a pilot project from 1 January 2017, to 31 December 2018 [72]. The pilot consisted of granting €560 as a tax-free monthly unconditional benefit to 2000 randomly selected unemployed people for two years. The amount was not reduced if they earned an income, and they were not obliged to search for jobs.

Kenya: In Kenya, a charity called Give Directly launched in October 2016 a pilot UBI experiment, consisting of giving a number of villages different amounts of money (from $22.50 to several hundred dollars) during different periods of time (between two and 12 years) and observing the results [73].

California: In Oakland, California, Silicon Valley’s largest startup accelerator, Y Combinator, announced in 2017 it would be paying $1000 per month for three to five years to 1000 randomly selected people (from a sample population of 3000 people) across two states [74].

In Stockton, California, the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED) project has been disbursing $500 per month to 130 recipients. This pilot project started in February, 2019, and will run for 18 months. In order to be eligible, recipients had to be over 18 years old and reside in a neighborhood where the median income was equal or below $46,003. The payments are made to recipients regardless of their employment status [75].

Canada: In Ontario, Canada, the Ontario basic income pilot (which began in June 2017) was designed to provide up to CA $16,989 for a qualifying low-income single person and $24,027 for a couple (less 50 percent of any earned income) for up to three years [75]. However, the pilot was cancelled by a new conservative government and the 4000 recipients received their final payments on 31 March 2019 [76].

Germany: In Germany, a new program will be launched in 2019 where 250 qualifying citizens will be “sanction free” for three years under the Hartz IV social security system, enabling them to retain their benefits (income) while trying to search for employment [77].

India: In India, two basic income experiments in the state of Madhya Pradesh were undertaken in 2010, in which more than 6000 people received small monthly payments for 18 months. The state of Sikkim now plans to provide a universal basic income to more than 611,000 inhabitants, making it the largest pilot program in the world [78].

Namibia: In Otjivero–Omitara, Namibia, a pilot project ran from January 2008 to December 2009. It provided a monthly income of N$100 per person. The payments were made to residents who were under 60 years old regardless of their employment status [79].

Mississippi: In Jackson, Mississippi, The Magnolia Mother’s Trust will be giving 15 low-income families headed by Africa American females $1000 per month for one year as part of a pilot project, more than doubling the annual income of these households [80].

Spain: In Barcelona, the City and collaborating partners have been providing payments to 1000 households since October 2017. The pilot will be running until September 2019. The monthly payments can be up to €403 to cover basic needs and up to €260 to cover main dwelling expenditures [81].

Uganda: In Uganda, starting in 2017 the nonprofit Eight began providing unconditional weekly cash transfers (through mobile payments) to 56 adults (USD ~$16) and 88 children (USD ~$8) in a rural village [82].

United Kingdom: Provided that Labour is in control of the government, the political party has promised to run a pilot project that provides weekly payments of £100 to every citizen, and an additional £50 for every child in the household, regardless of income or wealth. The trials would be tested in Liverpool, Sheffield, and in some locations in the Midlands [83,84].

United States: Since 1996, and with now nearly 13,000 members enrolled, the Eastern Cherokee Reservation has disbursed two annual payments from the profits generated by a casino. Recipients must finish high-school to start collecting payments at age 18. Otherwise, the disbursements are postponed until members turn 21. The average per capita payment is approximately $4000 per year [85]. However, the largest disbursement took place in December 2018 with a payment of $7007 before taxes [86].

The proposals listed in Table 1 provide a range of ways in which a version of more broadly distributed income via a UBI or a guaranteed job program could be used to address income needs and inequality, to different extents and in different ways.

The Negative Income Tax (NIT) proposal can be implemented in a variety of ways. It is based on the principle that people who work receive more income than those who do not, which, in theory, incentivizes work. While the NIT has a strong employment focus, it is not concerned with the potential technological displacement of work and has no explicit environmental considerations.

The Cost of Living Refund [88] proposal is a form of NIT and focuses on modernizing the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The proposal broadens the eligibility requirements to all workers over 18 and includes childless workers, caregivers, and low-income students. The proposal does not have any explicit environmental considerations.

The Federal Job Guarantee Program focuses on achieving full labor employment by providing a job to any individual willing to work at a specified wage. While there is a rich debate between the proponents of this type of “workfare” program [100,101] and the opponents who prefer a UBI [71,102,103], the focus here is on the scale of each program and its potential impact on inequality and the environment. When compared with a nation-wide UBI program, the targeted impact of the Jobs for All Act makes it considerably smaller (perhaps serving up to 10% of a developed economy’s labor force during a recession). This reduced scale would limit the environmental impact of the program, which does have an explicit focus on creating jobs with a minimal ecological impact. With regards to inequality, the program’s focus on creating employment opportunities in the areas of health, housing, education, and public infrastructure has the potential to reduce local inequalities but is unlikely to address the larger economy-wide polarization of the workforce and decline of meaningful middle-income jobs. The program also ignores unpaid reproductive and social roles and values people by their ability to earn a living through work [104].

UK Labour’s Inclusive Ownership Fund (IOF) is based on the argument that the financialization of the economy and concentration of corporate/economic ownership has led to the exclusion of workers (financially and politically) from the economy. The proposed plan is intended to provide both workers and society with a direct stake and say in the economy by reshaping the understanding of the firm under a “more pluralistic and inclusive vision” [105]. The Labour Party’s plan has no explicit concern for its potential impact on the environment from increased aggregate demand/consumption. Whereas Labour’s IOF proposal places workers first, the Citizen’s Wealth Fund at the center of Lansley and Reed’s [90] Fuller Basic Income (FBI) program would provide all British citizens with a direct ownership stake in, and income from, the fund. However, like Labour’s plan, the FBI program has no explicit components that target environmentally-sound investments or consumer spending. The idea of an IOF has also gained traction across the Atlantic, where Bernie Sanders is backing the approach as a way for workers to obtain a greater ownership stake and voice in companies, but the details of his proposal have yet to be articulated [106].

While Yang’s [11] proposal is based on the need to financially support workers because of technological (capital) displacement, the UBI financing mechanism is not linked to capital ownership. Due to its proven record outside of the U.S., a 10% value added tax (VAT) is considered to be an efficient mechanism to avoid corporate tax aversion. Yang’s [11] proposal has no explicit link between the growing aggregate demand it would likely generate and the environmental impacts of increased consumption. While Yang’s proposal built on Stern’s [91] earlier work, Stern’s UBI proposal presents a broader range of options to fund the basic income, including the idea of developing a common wealth fund based on Peter Barnes’ [97] UBI proposal (discussed below). If such a fund were to be established, it would link at least a portion of the UBI to an effort to protect ecosystems in the U.S.

The Assured Income [9] approach also includes a VAT as a potential revenue stream, along with taxes on unearned income, a carbon dioxide tax, and transaction fees on the trading of securities and derivatives. The monthly payments would be managed by the Social Security Administration (SSA). If a well-designed carbon dioxide tax is implemented, it could incentivize low-carbon investments, directly addressing the fourth environmental concern discussed previously.

Hughes’s [92] UBI proposal is financed using a tax on high-income earners that would be redistributed among adults earning less than $50,000 a year. The approach is based on the rationale that work (and its incentivization) is essential, but it does not consider the possible implications of technology-displaced employment or consider the environmental implications of increasing aggregate demand. Like the NIT, it is a redistribution approach to addressing income needs and inequality.

The Alaska Permanent Fund (APF), the American Solidarity Fund (ASF), and the Common Wealth Trust (CWT) proposals provide a useful array of options for financing national funds/trusts. These range from taxing non-renewable resources (APF), to voluntary contributions (combined with a range of other financing options) (ASF), to protecting critical ecosystems by levying fees on corporations for the sustainable use of renewable/non-renewable environmental resources (CWT). When viewed through an environmental lens, it is important to assess both the way the funds/trusts are (1) financed and (2) how the principal of the funds/trusts is invested/managed. In general, it is the profits from the managed investments that will finance a UBI via dividend payments.

With regards to the financing of the funds/trusts, the APF and CWT provide two different options that aim to address unsustainable economic activities and promote sustainability. The APF levies a 25% tax on mineral leasing rentals that provides a revenue stream for the fund, which is combined with income generated by the fund’s investments. The fund’s principal may not be spent without approval from Alaskan residents, but its reserve (the realized earnings from investments) can be spent. The financing approach aligns with Herman Daly’s proposal for “taxing the bads, rather than the goods,” and can be used to influence the rate of non-renewable resource extraction. However, there is no explicit consideration of the finite nature of mineral resources or how these could be managed for future generations. In contrast, the CWT proposal addresses these shortcomings. Barnes [97] (p. 2) claims that organized common wealth “can help fix the two greatest flaws in contemporary capitalism—its relentless destruction of nature and its equally relentless widening of inequality—while preserving the benefits markets can provide.” By putting critical ecosystems and resources under the management of CWTs, the managers of the funds would be required to protect their assets for future generations and to share current income obtained from their sustainable use. Since no CWTs have been created, specific questions on how these funds would be established and managed have yet to be answered. In addition, since citizens would be free to spend their income as they choose, the CWT proposal would not impact environmental/social problems related to the production and delivery of goods/services from outside of U.S. borders.

It can be argued that similar goals (preserving the life-sustaining capacity of the planet and addressing the widening wealth gap) can be achieved by taxing the use of public commons (i.e., the APF approach). Barnes [97] (p. 6), however, favors the creation of trust-administered property rights over redistributive taxation on the grounds that property rights tend to endure, whereas fiscal policies can fluctuate with the whims of politics.

With regards to investing the principal of the funds/trusts, the APF, ASF, and CWT present three approaches—(1) maximizing the return with no explicit concern for sustainable development (e.g., the APF); (2) maximizing the return, but without investing in firms engaged in human rights violations or environmental destruction (e.g., the ASF); and (3) maximizing the return, but with investments that focus on the sustainable use of resources for present and future generations (e.g., the CWT). The second approach is used by Norway to guide its sovereign wealth fund investments. The third approach has the potential to significantly advance the sustainable management of resources, but it is not clear how the principal of the CWT would be invested.

The final approach listed in Table 1 is based on Robert Ashford’s approach to inclusive capitalism. This approach to addressing inequality and advancing sustainability has similarities with several of the other approaches, but it also has significant differences. (1) Whereas the other strategies are based on what might be called the range of mainstream economic theories of growth, efficiency, and fuller employment, the inclusive capitalism approach is based on binary economics, which presently is not widely reflected in mainstream economics. As explained more fully below, binary economics adds a more nuanced understanding of growth, efficiency, and fuller employment by focusing on the distribution of capital acquisition with the future earnings of capital. (2) Consequently, only the inclusive capitalism approach recognizes the principle of binary growth (discussed below). (3) All of the other approaches require either redistribution from (or dilution of) existing wealth (including claims acquisition) or the distribution of public wealth (as in the case of the APF); whereas the more broadly distributed capital income associated with binary growth does not require redistribution. (4) As a further consequence, these other solutions compete with one another for the resources needed to supplement existing labor and welfare claims. In contrast, because it is premised on additional wealth creation incentivized by the broader distribution of capital acquisition, the inclusive capitalism approach does not require redistribution of existing wealth or distribution of public wealth, and is therefore an add-on, not a competitive alternative, to the other approaches. Rather than subtracting from the growth in wealth available for the other approaches, it adds to it.

The principle of binary growth distinguishes binary economics as a distinct paradigm for understanding market economics. The principle provides a theoretical foundation for structuring a private-property system that will tend to broaden rather than concentrate capital ownership and thereby produce enhanced earning capacity for poor and middle class people, greater and more broadly shared prosperity, and enhanced levels of sustainable growth [107] (p. 26).

To explain the fuller employment and per-capita growth potential of broadening capital acquisition with the earnings of capital, binary economists focus on the distinction between productivity and productiveness. Productivity is a ratio of all factors of production divided by one factor, usually labor; whereas, retroactively productiveness means “work done” and prospectively means “productive capacity” [98].

Although most people believe that the primary role of capital in contributing to per-capita economic growth is to increase labor productivity, there is another (binary) way to understand the primary role of capital: to do an increasing portion of the total work done. According to the widely shared perception, per-capita growth might be understood by considering the work of moving products (food, consumer goods, etc.) between points A to B. For illustration purposes, consider the ability of one person to move one unit of product between points A and B in a day, 100 units with the help of a horse, and 10,000 units with a truck. From a binary perspective, the horse and truck are doing more than enabling the person to do more work; they are doing more of the total work (the same can be said for any capital employed in production). Thus, per-capita growth can be understood as capital increasing labor productivity (mainstream view), or as capital doing an ever-increasing portion of the total work done (binary economics view). Through the lens of productiveness, binary economists believe that in a modern industrialized economy (1) capital, not labor, is doing most of the additional work and is thereby creating most of the additional wealth and (2) capital ownership (if broadly acquired) is capable of distributing much more income than can be achieved through wages alone.

Now consider what happens in the above example if an automated truck (with no driver) moves the product from point A to B. In this case, all of the physical work of moving the product is being done by capital. In this scenario, many (if not most) economists typically point to (1) the creation of new jobs (e.g., those in the automated vehicle management center, the jobs for software programmers needed to continually update/advance the automated-driving software, etc.), and (2) the additional jobs that may be created as a consequence of the economy-wide increase in productivity. However, this argument fails to address what is really happening at the task level. With driverless trucks, the physical work of moving a product from point A to B is being done entirely by capital. While such a transformation will certainly create some new jobs in the automated transportation and robotics industries, focusing on these new jobs (that have different task categories) ignores that the specific task of moving a product from point A to B is no longer linked to income from wages. Instead, the only way income can be distributed from this task without redistribution is via a capital ownership stake in the automated truck. Note also that the typical “new-jobs” and “more jobs” response fails to address the income distribution consequences that flow from the fact that labor’s contribution to total production has decreased and capital’s contribution has increased. Now consider what happens if this simple example is extrapolated to specific routine manual and cognitive tasks across the entire economy that have or could be displaced by capital. Consider also the fact that the number of jobs displaced from specific tasks (e.g., driving trucks, providing services at truck service stations, etc.) are rarely replaced by an equivalent number of new jobs (e.g., in the automated truck sector). There is also the critical question of whether a displaced worker can transition into any of the new jobs that may become available in an increasingly-polarized workforce.

The binary economics view of economic growth has profound implications regarding how people can most efficiently participate and share in economic growth. Conventional economists assume that the gains for most people must come via more jobs and higher wages, lower prices for goods and services, and welfare redistribution—all functions of labor productivity. Binary economists see far greater potential for most people via the broader distribution of capital acquisition with the future earnings of capital. They argue that if the effect of technological innovation is to both replace and vastly supplement the work of labor with increasingly productive capital, and thereby reduce the contribution of labor to production while increasing the contribution of capital, then the preservation and enhancement of individual earning capacity and optimization of growth in a market economy requires practical market mechanisms that enable all people to acquire a share of this growing capital productiveness [107] (p. 34). Like well-capitalized people, everyone needs the competitive opportunity to acquire capital, not merely with the earnings of labor, but also increasingly with the earnings of capital. According to Robert Ashford, a widespread understanding of the principle of binary growth will enable market participants, by way of non-redistributive, voluntary transactions, to do exactly that.

If the basic premise of binary economics—that a broader distribution of capital acquisition provides the rational expectation of more broadly distributed capital income (and consumer demand) in future years and therefore greater market incentives for the fuller employment of labor and capital (and economic growth) in earlier years—is valid, it has implications that either do not follow from conventional economic analysis or may significantly vary from it. Several of these implications are that this premise provides:

- an additional approach to fuller employment and per-capita growth;

- an additional approach to enhancing the earnings of poor and middle-class people in the age of automation/AI beyond minimum wage legislation, government jobs programs, and guaranteed minimum income (financed via redistribution mechanisms);

- a means to reduce the need for welfare distribution;

- an additional approach to environmental sustainability by (a) making greener technologies and regulations more affordable and politically achievable and (b) targeting ownership-broadening financing so as to promote the production of inherently sustainable goods and services;

- an additional approach to development and foreign assistance;

- an additional approach to globalization;

- an additional approach to privatization; and

- a means to reduce the need for economic immigration.

The present market approach to capital acquisition (which limits capital acquisition primarily in proportion to the existing distribution of wealth) constitutes a major obstacle to sustainability for several reasons, including the following: (1) market prices and the regulatory system do not sufficiently internalize the negative externalities of unsustainable production and consumption nor the positive effects of sustainable ones, especially in the long run; (2) limiting capital acquisition of increasingly capital intensive production primarily to people in proportion to the existing distribution of wealth needlessly deprives most people the competitive opportunity to acquire capital earning capacity thereby making greener technologies less affordable; and (3) conversely, broadening capital acquisition with the earnings of capital renders greener technology more affordable and investment in them more profitable, while reducing the perceived conflict between sustainability and labor employment. Thus, broadening capital acquisition with the earnings of capital on the corporate level, and consequently on the individual shareholder level to increase both individual earning capacity and corporate investment in inherently sustainable goods and services, is thus a crucial endeavor of sustainable development.

Inherently sustainable goods and services can be defined as those which exploit renewable resources “on a profit-maximizing sustained yield basis” [108] (p. 45). Further, the use of replenishable (i.e., non-living) forms of natural capital (e.g., groundwater and the ozone layer) should not exceed their rates of replenishment or recharge [109]. The use of nonrenewable resources should be minimized and used in cradle-to-cradle (closed loop, circular economy) systems [110]. Such fundamental principles could be incorporated into a government-backed set of criteria for inherently sustainable goods and services, which could provide important market signals in much the same way as the U.S. ENERGY STAR system. With bank loans secured by private capital credit insurers, ownership-broadening trusts (Binary Trusts) could invest (on behalf of designated beneficiaries) in common stock voluntarily issued by companies that are advancing inherently sustainable forms of development. The trust could go one step beyond Norway’s list of excluded companies [111] by reviewing investments using lifecycle assessment and other accepted forms of sustainability analysis. In addition, the trust could finance the growth of employee-owned B Corporations that frequently outperform investor-controlled corporations from an environmental and social perspective [112].

Point 4(b) above directly focuses on the growth that an inclusive capitalism approach would generate from the development of inherently sustainable goods and services. Financing a transition to sustainability in this way would result in citizens/residents having a direct ownership stake (and voting rights) in the future (sustainable) economy, which could also have a powerful educational and economic democracy value. We believe that directly linking investment, more broadly distributed ownership, and spending on the consumption of the inherently sustainable goods and services created provides an alternative development paradigm that can grow to replace unsustainable production and consumption systems.

3. An Integrated and Environmentally Sustainable Approach to Providing a UBI

As advanced in this paper, inclusive capitalism based on binary economics recognizes that knowledge (i.e., technology) reflected in the understanding, training, and skills of people enables them to work more productively. It also recognizes the far greater ability of technology embedded in capital to do an ever-greater share of the work. This recognition mirrors Yang’s [11] thesis of the major driving forces of inequality and technology’s ability to claim in market transactions an ever-greater share of the value being created for those who own the capital. But in contrast to Yang, inclusive capitalism makes available to people (with little or no capital) the voluntary process of capital acquisition of, and thereby ownership in, the very technologies that are displacing workers the principle mechanism for addressing inequality. The IOF, APF, ASF, and the CWTs also have capital ownership as a core or supplemental part of their UBI, with or without explicit citizen/resident ownership of the capital/shares. In contrast to these funds/trusts, inclusive capitalism trusts (Binary Trusts) could invest in inherently sustainable goods and services in a way that would provide citizens/residents with ownership of, and a future income stream (dividend payment) from, these investments. By limiting the opportunity of ownership-broadening binary financing to sustainable production, this approach would create a structural change to investment that specifically encourages and promotes the development of more sustainable products and services. Put differently, the approach would begin to close the production, distribution, and consumption loop and generate future markets for inherently sustainable goods and services. The investment decision makers working for Binary Trusts would need to be able to integrate knowledge relating to corporate finance, green/sustainable engineering, environmental/ecosystem science, etc., and be highly competent with a broad array of environmental assessments techniques, such as life cycle analysis (LCA) and environmental/sustainability certification schemes.

The Binary Trusts would be private entities that would act independently from government. The institutions that can be used most effectively to competitively acquire capital with the earnings of capital in an ownership-broadening way are (1) the largest three thousand or so credit-worthy corporations (roughly comprising the Russell Index) working cooperatively with (2) professional Binary Trust fiduciaries (such as Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, TIAA-CREF, and Vanguard), (3) private lenders, and (4) private capital credit insurers. The capital acquisition approach would work as follows [113,114]. First, corporations that meet the government-backed inherently sustainable criteria would need to decide to finance their growth by selling common shares to a Binary Trust. This corporate decision would be based on an expectation that (1) the binary growth mechanism presents the best long-term growth potential for the corporation when compared with all other corporate finance options and (2) any financing received from the Binary Trust would provide a powerful market signal that the corporation is investing inclusively and sustainably. After a corporation makes this decision, the Binary Trust would then need to decide whether to purchase the shares (with bank loans secured by private capital credit insurers) and, in doing so, certify that the corporation’s planned growth (1) conforms with the established criteria for investing in inherently sustainable development and (2) is in the best interest of the Trust’s beneficiaries. Likewise, private lenders and capital credit insurers would need to be satisfied that the loans and insurance needed to finance the corporate capital acquisition are the best use of their available resources. This process of ownership-broadening binary financing is driven by market incentives with the winners being (1) the most competitive corporations seeking to advance sustainable production and consumption systems, (2) the Binary Trusts and their beneficiaries who will receive an income earned from these emerging systems, and (3) the lenders and capital credit insurers earning the best returns from their lending and insuring decisions, respectively. Thus, although the government would determine the sustainability standards needed to qualify for ownership-broadening financing, private decision-making subject to competitive market forces (not government) would determine the winners and losers in the financing and provision of goods and services and the resultant distribution of ownership and income. A more detailed description of ownership broadening financing based on binary economics can be found in [70,114].

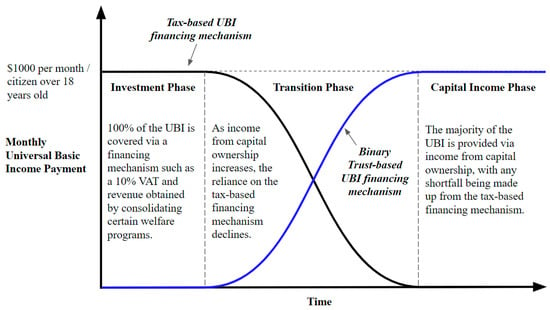

A valuable feature of a binary economics approach to inclusive capitalism is that it does not exclude the use of other financing mechanisms to provide a basic income—as mentioned previously, it adds to wealth. In fact, during the launch of an inclusive capitalism UBI program, other mechanisms may be required to ensure the agreed upon basic income can be paid to citizens while the capital invested by a Binary Trust pays for itself out of its future earnings. Figure 6 provides a visualization of this mechanism. For the purposes of this example, let’s assume that the agreed upon basic income will be $1000 per month for every citizen over the age of 18—i.e., Yang’s [11] proposed amount. During the Investment Phase, 100% of the basic income could be paid for via a 10% VAT combined with a consolidation of certain welfare programs. During this same period, the Binary Trust would begin the process of purchasing special full-dividend common shares from creditworthy corporations that are seeking capital to invest in inherently sustainable goods or services. These shares would be paid for with a bank loan to the Binary Trust, which is insured by a private capital credit insurer and a government reinsurer. Robert Ashford [99] (p. 20) explains that “once the capital acquisition loan repayment obligations are met, the full net capital earnings (net of reserves for depreciation, research, and development) would be paid to [… citizens] to help enable them to meet their needs and wants and to provide the basis for increased investment and production.” For example, if the expected timeframe for capital to pay for its acquisition cost (i.e., repay its acquisition debt obligations) out of its future earnings is between five and seven years, then (depending on the loans terms) the Binary Trust might make no contribution to the UBI payment during the initial Investment Phase (i.e., the capital cost repayment period).

Figure 6.

Providing a universal basic income (UBI) by integrating financing mechanisms. Note: This figure shows how, during the Investment Phase, the process of capital acquisition can be employed to (1) first acquire capital with capital credit repaid with its earnings and (2) progressively replace redistributed income used to initially fund the UBI during the Investment and Transition Phases.

During the Investment Phase and into the future, each year the Binary Trust would make a certain number (N) of investments which, if successful (net of investment losses), would pay for themselves with the future earnings of capital, growing the share of the UBI that could be covered by this financing mechanism. The Transition Phase begins the moment the Binary Trust-based financing mechanism has satisfied its obligations to repay the acquisition costs of a particular investment and starts to pay citizens an income from their share of the newly acquired capital managed by the Binary Trust. As the scale of Binary Trust investments grow, the share of the UBI covered by this financing mechanism would also grow as indicated conceptually in Figure 6. During this same period, the taxes used to finance the UBI during the Investment Phase could be reduced or the funds collected and not allocated to the UBI could be used to support other government initiatives.

Finally, during the Capital Income Phase the majority or all of the UBI would be provided to citizens from the dividend payments they receive from capital, with the tax-based UBI financing mechanism making up for any shortfall.

Of course, depending on the loan terms of specific ownership-broadening financings, in any year in which the Binary Trust’s income exceeds that year’s annual acquisition debt repayment obligation, trust income could be distributed in that year to the beneficiaries. Thus, the Transition Phase could begin years before the acquisition loan is fully repaid.

The above example outlines an inclusive capitalism approach to providing a UBI that is (1) grounded on an economic theory that explains the powerful role of technology in the modern economy, (2) provides citizens with a direct capital ownership stake in, and income (via dividend payments) from, the future growth of the economy, and (3) incentivizes investment in inherently sustainable goods and services. If the income received from capital were then spent on the inherently sustainable goods and services, this would create a circular flow of money and provide more incentives for corporations to finance their growth using the Binary Trust, furthering efforts to incentivize sustainability investments. This integrated approach presents a promising mechanism to realize the massive and targeted investments needed to transition to low-carbon technology and address other critical environmental challenges.

4. Conclusions

This paper explores the major drivers to income/wealth inequality and presents modern technology/AI as an emerging force that is likely to continue intensifying the rate at which capital is driving productivity at the expense of labor. Given the growing concern at increasing levels of inequality in many nations, the idea of providing a universal basic income (UBI) is gaining traction. However, few approaches (1) are based on an economic theory that helps explain the growing inequality, (2) highlight the potential environmental problems that a UBI might create with regard to growing effective (aggregate) demand/consumerism, and (3) present a voluntary way to finance a transition towards sustainable production and consumption.

This paper reviews a broad range of proposals for providing a UBI and highlights how they rationalize the need for a basic income, how each proposal would work, and whether there is any attempt to connect the approach with strategies to advance sustainable development. Proposals that finance a UBI without considering the consumption-related environmental impacts from increasing effective demand or how the approach will enable a transition to sustainability present only a partial, non-integrated solution to the economic inequality and sustainability challenge.

To address this problem, the approach to inclusive capitalism advanced by Robert Ashford, premised on binary economics, is presented as a promising way to reduce economic inequality and advance sustainability. In contrast with the other proposals, an inclusive capitalism approach could be used to invest in inherently sustainable goods and services in a way that would provide citizens with ownership of, and a future income stream (dividend payment) from, these investments. This approach would begin to close the production, distribution, and consumption loop and generate future markets for inherently sustainable goods and services. Further, the flexibility of the approach means that it not only could be applied without significant disruption to existing and proposed mechanisms for addressing inequality, but also has the potential to profitably supplement, reduce, and replace reliance on these approaches as the extent of capital ownership and income received from this ownership grows. Because the income benefits of the inclusive capitalism approach would be distributed through the property system, the approach may be less vulnerable to the politics of changing administrations, which could easily reduce or halt any UBI program based on tax revenue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.H., R.A. and N.A.A.; methodology, R.P.H.; investigation, R.P.H., R.A., N.A.A. and J.A.-Q.; resources, R.P.H., N.A.A. and J.A.-Q.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.H. and R.A.; writing—review and editing, R.P.H., R.A., N.A.A. and J.A.-Q.; visualization, R.P.H., J.A.-Q. and R.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding, but support was provided by (1) the College of Architecture and Urban Studies (CAUS) at Virginia Tech and (2) the Canadian Society for Ecological Economics (CANSEE) to enable the first author to present an early draft of this work at conferences in the UK and Canada, respectively. We are also grateful to the Virginia Tech Open Access Subvention Fund for covering the article processing charges for this paper.

Acknowledgments

An earlier draft of this paper was presented at a conference on Endogenous Growth, Participatory Economics, and Inclusive Capitalism at St. Bennet’s Hall, Oxford University, on 9 February 2019, and the Canadian Society for Ecological Economics 12th Biennial Conference, from 22–25 May 2019, Waterloo, Canada. The paper also draws on analysis in [8]. Finally, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers who helped advance the scope and content of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Strategies to address income inequality.

Table A1.

Strategies to address income inequality.

| Scheme/Program | Financing Mechanism | Income/Money Flow | Comments | Environmental Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Negative Income Tax (NIT) (inspired by Milton Friedman [87]) | A Negative Income Tax (NIT) system would tax individuals earning an income above a specified income threshold and redistribute this income to individuals earning less than the threshold. The amount of taxes paid or received would depend on the tax rates and how far an individual’s income falls above or below the threshold, respectively. | An income would only be received by individuals whose income falls below a specified income threshold. The amounts received would vary by individual. | If implemented following Friedman’s approach, the NIT would be designed to replace all welfare and assistance programs, with the specified income threshold set at a level that would still encourage people to work. | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Cost of Living Refund [88] | Modernization of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) (also known as the Working Families Tax Credit) | Single people earning less than $50,000 a year would receive $4000 per year. Married couples earning less than $90,000 a year would receive $8000 per year. The payments can also be received monthly. | Over the past several years, a broad range of legislation has been proposed to modernize the EITC [115]. The Cost of Living Refund approach builds on these proposals and targets low-income and middle-class families by broadening eligibility to all workers aged 18+, including “childless” workers, and expanding the definition of work to include family caregivers and low-income students. | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Federal Job Guarantee Program (H.R. 1000−Jobs for All Act−submitted to the 116th U.S. Congress) | A National Full Employment Trust Fund (NFETF) would be held in the U.S. Treasury and funds would be appropriated to the NFETF from three sources (Sec. 102(1–3)): (1) revenues generated from a financial transaction tax (FTT); (2) funds from the Federal Unemployment Trust Fund that would have been provided to an unemployed individual if they were not participating in the proposed guarantee job program; and (3) an amount equal to the FICA (Federal Insurance Contributions Act), Medicare, and personal income taxes paid by participants in the proposed guarantee job program on their program earnings. Loans can also be made to the NFETF from the Federal Reserve to make up for any shortfall in the program, but these would need to be repaid (with interest equivalent to the return on 10-year Treasury bonds) over ten years unless the Federal Reserve decides that canceling the loans would have no negative effects on the economy. | The Federal Job Guarantee Program would prioritize the award of Employment Opportunity Grants to projects that provide affordable housing, childcare, transportation, and job training in areas with the greatest economic need. Participants enrolled in a work program would receive compensation that is comparable to public sector employees undertaking similar work (or work of comparable worth) in the geographic region of the program participant (Sec. 305(1)(D)). Participants enrolled in a job-training program would be eligible for a cost-of-living stipend set by standards established by the Secretary of Labor (Sec. 305(2)(A)). | The Jobs for all Act is based on the premise of the ‘right to work,’ whereas the other strategies included in this analysis primarily focus on ways to provide income support in the context of growing inequality. Of course, such support could help realize the human right to food, housing, healthcare, etc.In the context of this paper, a critical question is how resistant the jobs created by such a program would be to technological displacement? | The Federal Job Guarantee Program would require that all funded projects be carried out “in a manner that is as ecologically sustainable as is reasonably possible” (Sec. 304(10)). While a necessary requirement to limit the environment impacts of the program, the scale of the number of jobs created is unlikely to have a significant impact on the environmental performance of the U.S. economy. |

| UK Labour−Inclusive Ownership Fund (IOF) [89] | Companies with 250 or more employees would create an “inclusive ownership fund” (IOF) and transfer at least 1% of their ownership to this fund each year, up to a maximum of 10%. Smaller firms could set-up an IOF on a voluntary basis. The IOFs would be held and managed collectively, and shares would be non-tradeable. Fund representatives would have voting rights in a companies’ decision-making processes. | Workers in a firm with an IOF could receive up to £500 per month, after which any remaining dividends would be paid into a national fund to support public services and welfare programs. | The IOF scheme was proposed by the UK Labour Party in 2018. If implemented, the scheme could benefit 10.7 million people (40% of the private sector workforce). | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Lansley and Reed’s [90] Partial Basic Income (PBI) Proposal in the UK | The Partial Basic Income (PBI) program is estimated to cost about £300.2 billion per year, of which £118.2 billion would be covered by eliminating child benefit payments and state pensions and reducing means-tested benefits. The remaining £182 billion would come from eliminating personal allowance payments and increased national insurance and income tax rates. | Every British citizen would receive a weekly tax-free payment of £40 for those younger than 17 (£2080 annually), £60 for those aged 18–64 (£3120 annually), and £175 for people older than 65 (£9100 annually). Couples under 65 would receive £120 per week (£6240 annually), couples with one child would receive £160 (£8320 annually), and couples with two children would receive £200 (£10,400 annually). | The PBI program is designed to be revenue neutral, making it an implementable first step towards a Fuller Basic Income (FBI) program (see below). It is also designed to make the tax system more progressive. | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Lansley and Reed’s [90] Fuller Basic Income (FBI) Proposal in the UK | The Fuller Basic Income (FBI) program would build on the PBI (discussed above) and increase the weekly payments. The additional £26 billion a year needed to provide the higher weekly payments would come from a Citizen’s Wealth Fund created at the start of the PBI program, which would take some 20 years to reach maturity and start payments. The fund could be developed by transferring a range of existing commercial and public assets and profitable state-owned enterprises into the fund, one-off taxes on windfall profits, payments from corporations for the use of personal data, and increased taxation on wealth. In addition, large corporations could issue 0.5% of new shares annually that would pay directly into the fund, up to a maximum of 10% over 20 years (an approach that is similar to the IOF discussed above). It is estimated that the fund would need to reach £650 billion to provide the £26 billion needed for the higher basic income payments. The fund would be managed with a long-term investment horizon and kept in trust in perpetuity. All British citizens would have a direct ownership stake in the fund. | The FBI program would increase the PBI weekly payments. Every British citizen would receive a weekly tax-free payment of £50 for those younger than 17 (£2600 annually), £80 for those aged 18-64 (£4160 annually), and £180 for people older than 65 (£9360 annually). Couples under 65 would receive £160 per week (£8320 annually), couples with one child would receive £210 (£10,920 annually), and couple of two children would receive £260 (£13,520 annually). | The FBI program’s focus on capital ownership is intended to provide all British citizens with a stake in the future of the economy. The independence of the Citizen’s Wealth Fund from the state is considered as necessary to protect the fund from government interference and provide greater income security, independent of government, to future generations. Interestingly, the fund’s ownership of corporate shares is considered as one way for citizens to financially gain from job-displacing productivity growth from AI/automation (see the discussion below on binary economics). | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Andy Stern’s [91] Universal Basic Income (UBI) Proposal | The Universal Basic Income (UBI) would be funded using a broad range of options, including: (1) eliminating many of the existing 126 welfare programs; (2) eliminating/reducing the government’s tax expenditures (e.g., removing tax deductions); (3) implementing a 5%–10% value added tax (VAT) on goods and services; (4) implementing a financial transaction tax (FTT); (5) creating a “common wealth” fund based on Peter Barnes’ idea for a Common Wealth Trusts (see below); (6) establishing a 1.5 percent wealth (or net worth) tax on personal assets over $1 million; and (7) considering ways to reduce government expenditure related to military spending, farm subsidies, subsidies to oil and gas companies, etc. | Every U.S. Citizen between 18 and 64 would receive $1000 a month, regardless of income or employment status. All senior citizens who do not receive at least $1000 per month in Social Security payments would also receive $1000 per month. | Stern’s [91] proposal is based on the premise that efficiency and labor productivity will continue to undermine/replace jobs, forcing people into more contingent forms of employment. | The proposal has the potential to consider the environmental impacts related to a UBI, but only if a common wealth fund is created based on the principles discussed by Common Wealth Trusts (CWTs)—see below. There is also the critical questions of the relative scale of the critical ecosystems that would be put into trust and the contribution of the common wealth fund to the UBI when compared to the other funding options—i.e., the greater the contribution, the greater the potential for consumer education and environmental protection. |

| Andrew Yang’s [11] Universal Basic Income (UBI) Proposal | A 10% value added tax (VAT) on the production of goods or services a business produces. Certain welfare programs (unspecified) would be consolidated. | Every U.S. citizen over the age of 18 would receive $1000 a month, regardless of income or employment status. If Andrew Yang is elected as U.S. President in 2020, the scheme would start in January 2021. | Like Stern’s [91] proposal, Yang’s [11] plan is based firmly on the idea that automation and AI are displacing jobs and that a UBI is necessary given the continued impact of this displacement. Yang also argues that the UBI would result in job growth from the increased effective demand among consumers and the need for industry to increase production to meet this demand. | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Assured Income [9] | Revenue streams from a range of potential sources would be deposited in a trust fund managed by the Social Security Administration (SSA). These sources include a value added tax (VAT), taxes on unearned income, a carbon dioxide tax, and transaction fees on the trading of securities and derivates. | Children (0–17) would receive $100–$200 per month; working age adults (18–64) would receive $200–$400 per month; older individuals (64+) would receive $100–$200 per month | The proposed program would benefit 326 million people. At the lower-benefit level, the cost of the program would be $632.4 billion. At the higher-benefit level the cost would be $1.265 trillion. An interesting aspect of the proposal is that the SSA could be authorized to invest in securities other than Treasury bonds, enabling the trust to act like a pension fund or Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Chris Hughes’ [92] Guaranteed Income for Working People | A tax on annual incomes of $250,000 or more would be used to underwrite the program. | A guaranteed income of $500 a month would be provided to every working adult who lives in a household with an annual income of less than $50,000. | It is estimated that 60 million adults would receive the guaranteed income at an annual cost of $290 billion. The program is designed to encourage work. | The program has no direct components that could improve the environmental performance of firms or shape consumer spending. |

| Iran’s Cash Transfer Program [93,94] | In 2010, Iran enacted a cash transfer program (via the Targeted Subsidy Reform law) to provide its citizens with a universal and unconditional income. The program is funded from revenues generated from removing price subsidies on fuel and food that accounted for around 80% of all subsidies. The program did not require new claims from the national budget, nor did it use oil export revenues. | In 2012, the program was providing monthly payments of 455,000 rials (worth USD $40 in 2012 and around $11 today) for approximately 70 million citizens (95 percent of Iran’s population). The transfers do not eliminate existing benefits. | In 2012, the program costs exceeded the available tax revenues by one third, forcing the government to print money that caused significant inflation (up to 40% in 2013), undermining the early gains made by the program. In 2016, the Iranian Parliament approved a bill to cut the cash payments to 24 million Iranians who already receive social welfare and who work in the public sector. | The removal of price subsidies on fuel can be viewed as a tax on the present consumption of oil. All countries (not only resource-rich ones) could use this scheme to ensure consumers pay the full market price for fuel. |

| The Alaska Permanent Fund (APF) [95] | At least 25% of all mineral lease rentals, royalties, royalty sale proceeds, federal mineral revenue sharing payments, and bonuses received by the State are placed in the Alaska Permanent Fund (APF)—valued at $64.9 billion (2018). The fund’s principal should be used for income-producing investments and cannot be spent without a constitutional amendment approved by Alaskan voters. | Each year, the Permanent Fund Dividend program provides Alaska residents with an annual dividend payout that typically falls between $1000–$2000. | The residents of Alaska have consistently voted to protect the Alaska Permanent Fund against efforts to use the fund’s principal to cover government deficits/spending. | While the APF is invested globally across seven asset classes—(1) Public Equities, (2) Fixed-Income Plus, (3) Private Equity and Special Opportunities, (4) Real Estate, (5) Infrastructure, (6) Absolute Return Strategies, and (7) Allocation Strategies—there is no explicit strategy to target sustainable investment opportunities. |

| American Solidarity Fund (ASF) [96] | The American Solidarity Fund (ASF) would be made up from a combination of voluntary contributions, ring-fencing existing state assets, levies (taxes and fees), leveraged purchases, and monetary seigniorage. The ASF would be managed by a public entity (a new state-owned enterprise—e.g., the America Solidarity Fund Corporation) to generate investment returns that would fund a universal basic dividend for U.S. citizens. | Every U.S. citizen over the age of 17 would be given one nontransferable share of ownership in the ASF, which would entitle them to receive a Universal Basic Dividend (UBD). The UBD would be equal to a five-year moving average of a percentage of the ASF’s market value. The amount received each year would depend on the size of the ASF and its five-year performance. | In contrast to the Alaska Permanent Fund, the ASF would provide citizens with a formal ownership share that cannot be sold and would return to the ASF upon death. | The allocation of the ASF’s assets would be determined by Congress or Treasury mandates. Companies could be excluded from the fund if they violate established guidelines—e.g., engage in human rights violations or environmental destruction. (The ASF could model their list of excluded companies following Norway’s sovereign wealth fund exclusion list [111].) |