Young Children’s Contributions to Sustainability: The Influence of Nature Play on Curiosity, Executive Function Skills, Creative Thinking, and Resilience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Nature Play and Nature Preschools

It is through play that children at a very early age engage and interact in the world around them. Play allows children to create and explore a world they can master, conquering their fears while practicing adult roles, sometimes in conjunction with other children or adult caregivers. As they master their world, play helps children develop new competencies that lead to enhanced confidence and the resiliency they will need to face future challenges. Undirected play allows children to learn how to work in groups, to share, to negotiate, to resolve conflicts, and to learn self-advocacy skills. When play is allowed to be child driven, children practice decision-making skills, move at their own pace, discover their own areas of interest, and ultimately engage fully in the passions they wish to pursue.[17] (p. 183)

2.2. Curiosity

2.3. Executive Function Skills

2.4. Creative Thinking

2.5. Resilience

2.6. Synthesis

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

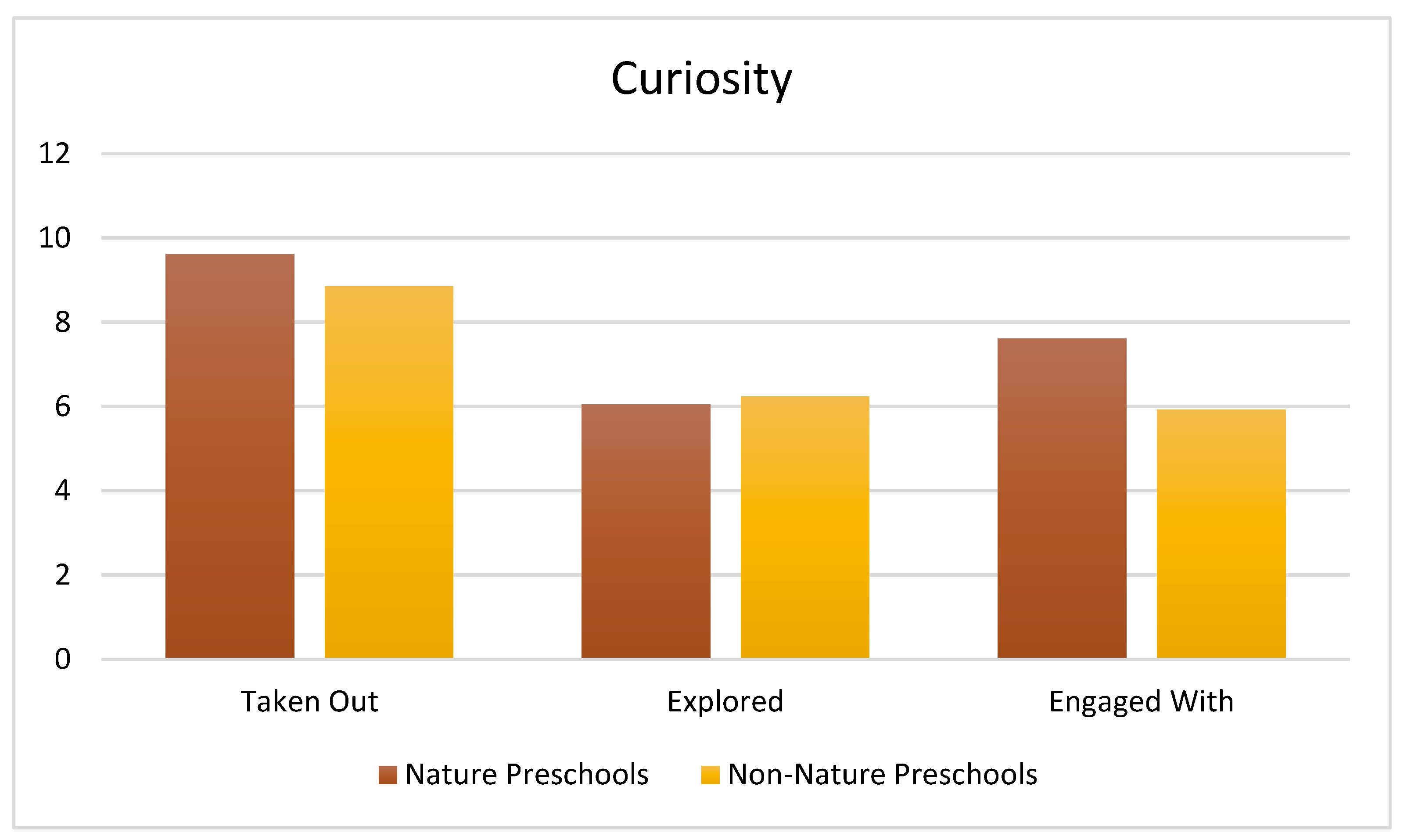

4.1. Curiosity Pilot Study

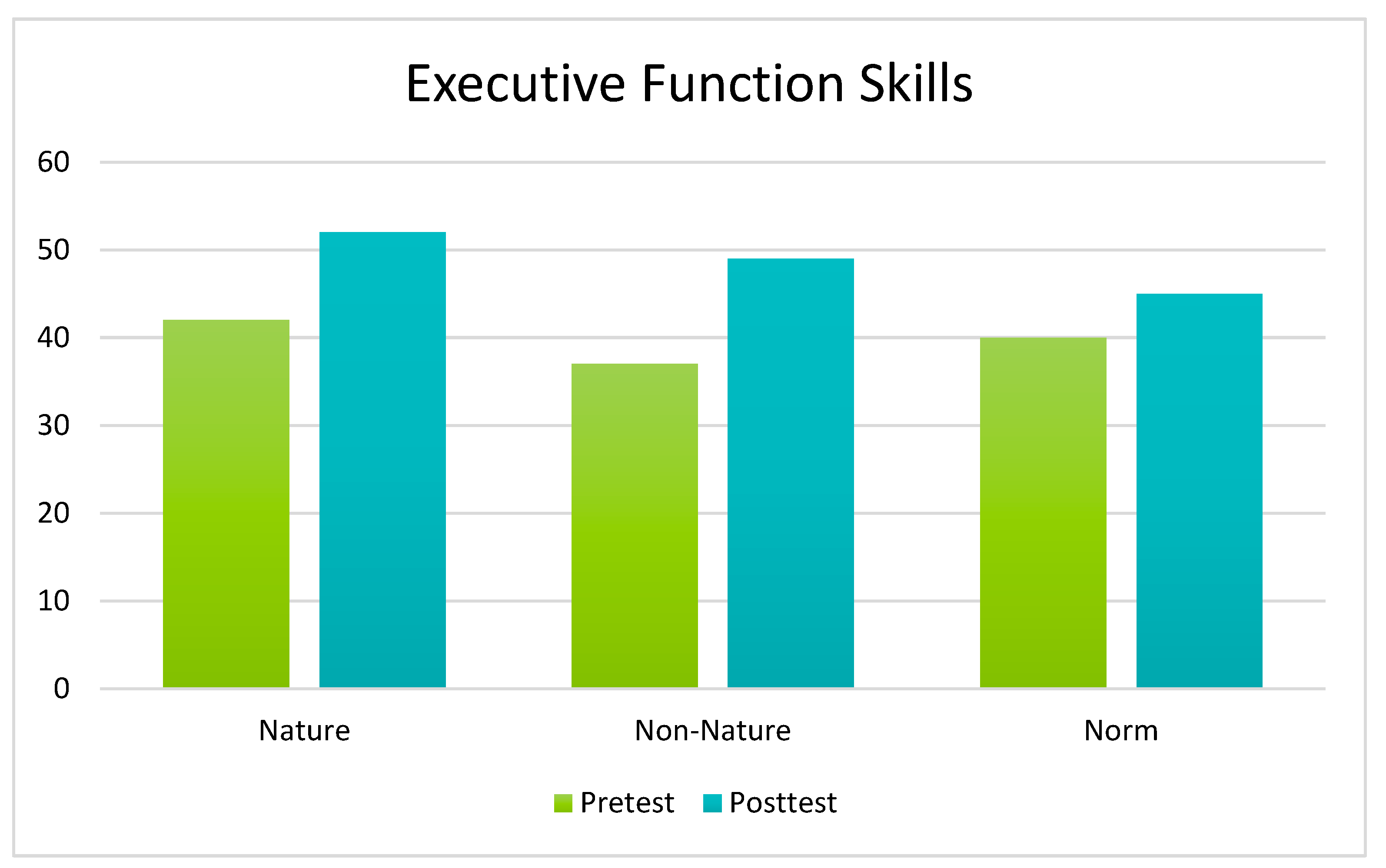

4.2. Executive Fucntion Skills Pilot Study

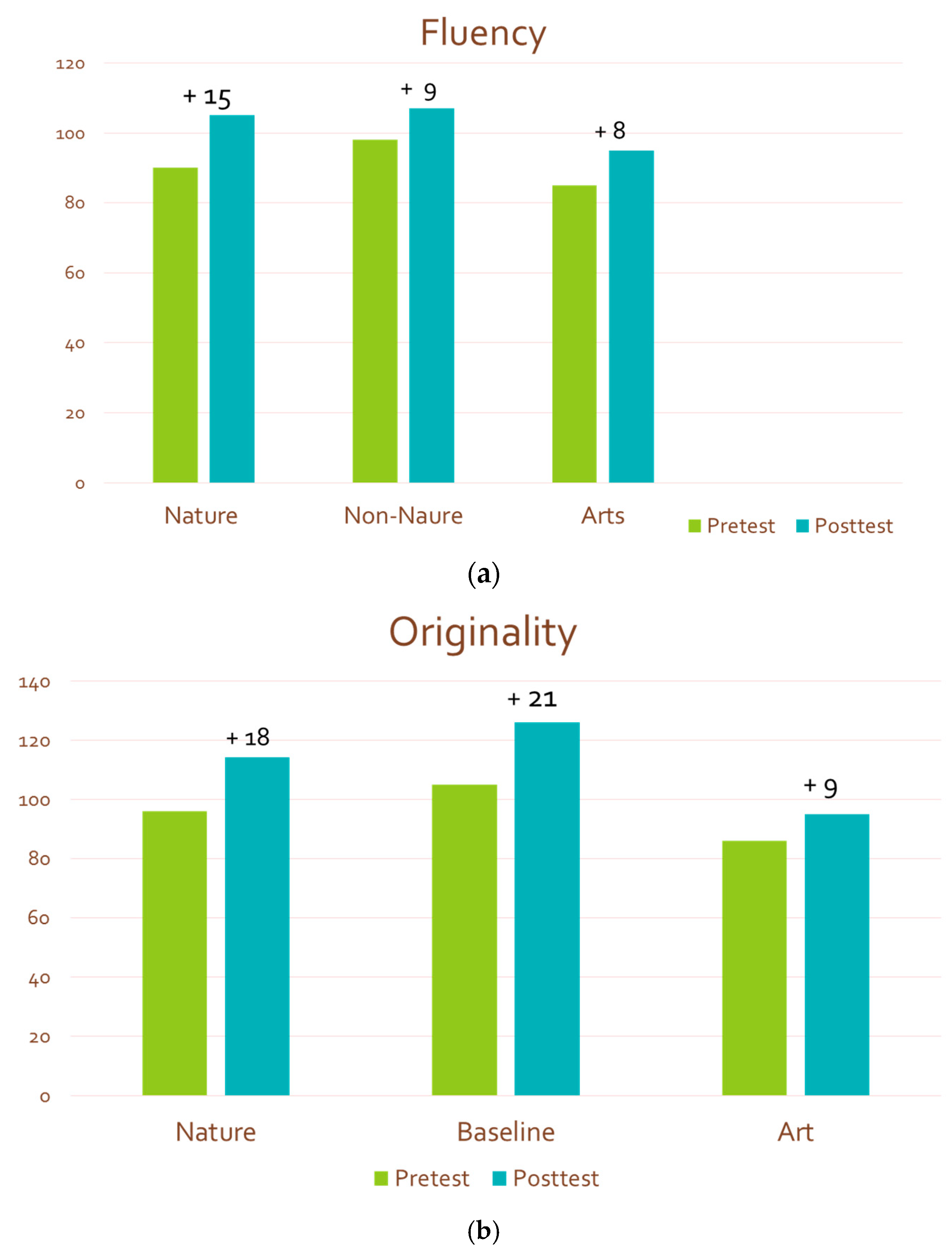

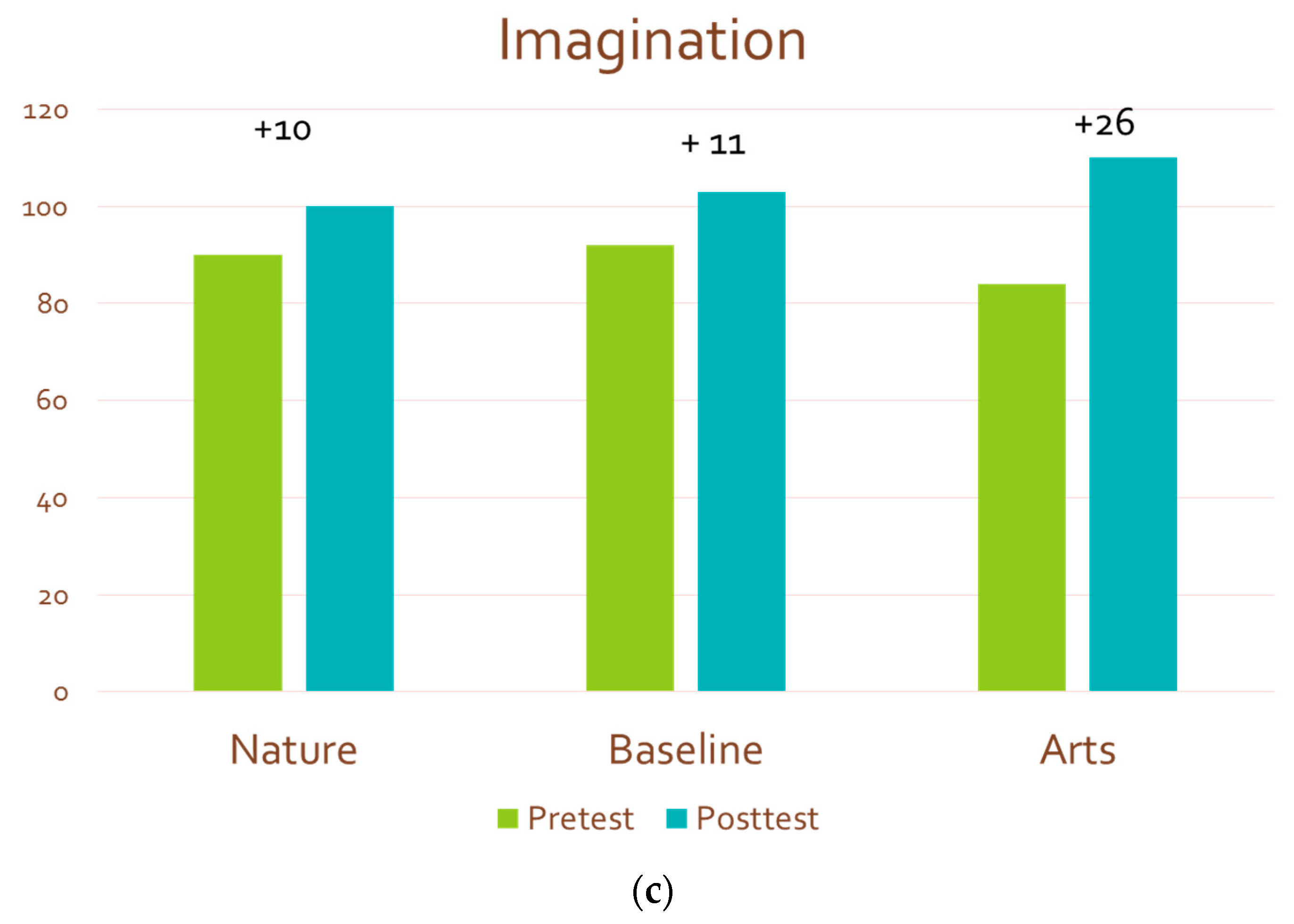

4.3. Creative Thinking Pilot Study

- “How Many Ways” asks participants to think of different ways to move from one side of the room to the other and is scored for fluency and originality;

- “Can You Move Like?” asks participants to take on six different roles, which are scored for imagination on a Likert scale ranging from “no movement” to “excellent, like the thing;”

- “What Other Ways?” asks participants to think of as many ways as possible to place a paper cup in a waste basket and is scored for fluency and originality; and

- “What Can You Do with a Paper Cup?” asks participants to think of as many ways as possible to play with a paper cup and is scored for fluency and originality.

4.4. Resilience Pilot Study

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samuelsson, I.; Kaga, Y. The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R. Nature and Young Children: Encouraging Creative Play and Learning in Natural Environments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fjortoft, I. Landscape as playscape: The effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development. Child. Youth Environ. 2004, 14, 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.E.; Huang, J.Y.; Bargh, J.A. The Scaffolded Mind: Higher mental processes are grounded in early experience of the physical world. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phenice, L.; Griffore, R. Young children and the natural world. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2003, 4, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Lekies, K.S. Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Child. Youth Environ. 2006, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, A.; Place, G.; Sibthorp, J. Early-life outdoor experiences and an individual’s environmental attitudes. Leis. Sci. 2005, 27, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North American Association for Environmental Education. Early Childhood Environmental Education Programs: Guidelines for Excellence; NAAEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the Twenty-First Century; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Elliot, S. (Eds.) Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: International Perspectives and Provocations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, S. Provocations for the “next big thing” in early childhood education for sustainability. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2019, 4, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Ed. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.; Wolf-Watz, D. Nature to place: Rethinking the environmental connectedness perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Marcus, C. Healthy planet, healthy children: Designing nature into the daily spaces of childhood. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Kellert, S., Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, T. The Best Schools: How Human Development Research Should Inform Educational Practice; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McCain, M.; Mustard, J.; McCuaig, K. Early Years Study 3: Making Decisions, Taking Action; Margaret & Wallace McCain Family Foundation: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg, K.; Committee on Communications; Committee on Psychological Aspects of Child and Family Health. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Am. Acad. Pediatr. 2006, 119, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.; Maudsley, M. Play, Naturally: A Review of Children’s Natural Play; National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2007.

- Noren-Bjorn, E. The Impossible Playground; Leisure Press: West Point, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, S. Children in the natural world. In Young Children and the Environment: Early Education for Sustainability; Davis, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2010; pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, N.; Evans, G. Nearby nature: A buffer of life stress among rural children. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C. Resurrecting free play in young children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, D.; Ernst, J. The real benefits of nature play every day. Exchange 2011, 33, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Banning, W.; Sullivan, G. Lens on Outdoor Learning; Redleaf Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Start Alliance and North American Association for Environmental Education. Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens National Survey; Natural Start Alliance and North American Association for Environmental Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://naturalstart.org/sites/default/files/staff/nature_preschools_national_survey_2017.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Larimore, R. Defining nature-based preschools. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2016, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P.E.; Weeks, H.M.; Richards, B.; Kaciroti, N. Early childhood curiosity and kindergarten reading and math academic achievement. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 84, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudeyer, P.Y.; Kaplan, F.; Hafner, V. Intrinsic motivation systems for autonomous mental development. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 2007, 11, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlyne, D.E. A theory of human curiosity. Br. J. Psychol. 1954, 45, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, J.K. Digitally Curious: A Qualitative Case Study of Students’ Demonstrations of Curiosity in a Technology-Rich Learning Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA, 2011. Available online: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc84250/ (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Dijkgraaf, R. Knowledge is infrastructure. Sci. Am. 2017, 316, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyler, E.; Wellings, L. Cultivating Joy and Wonder: Educating for Sustainability in Early Childhood; Shelburne Farms: Shelburne, VT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi, Y.; Chevalier, N.; Zelazo, P. Development of executive function during childhood. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Blair, C.B.; Willoughby, M.T. Executive Function: Implications for Education. National Center for Education Research; Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Cloud, J. Education for Sustainability: Standards and Performance Indicators; Cloud Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Lubart, T.I. Investing in creativity. Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A.; Jaeger, G.J. The standard definition of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. Imagination. In Encyclopedia of Creativity, 2nd ed.; Runco, M.A., Pritzker, S.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 637–643. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123750389001187 (accessed on 29 June 2019).

- Greenhill, V. 21st Century Knowledge and Skills in Educator Preparation: The Partnership for 21st Century Learning; Partnership for 21st Century Knowledge and Skills: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Wolfe, R. New Conceptions and Research Approaches to Creativity: Implications of a systems perspective for creativity in education. In The Systems Model of Creativity: The Collected Words of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S. Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.; Cicchetti, D. Resilience in development: Progress and transformation. In Developmental Psychology, 3rd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 271–333. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.; Masten, A. Resilience processes in development: Fostering positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In Handbook of Resilience in Children; Goldstein, S., Brooks, R., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, P. Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- LeBuffe, P.; Naglieri, J. Devereux Early Childhood Assessment for Preschoolers Second Edition: User’s Guide and Technical Manual; Devereux Center for Resilient Children: Villanova, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, B.; Moore, C. Measuring exploratory behavior in young children: A factor-analytic study. Am. Psychol. Assoc. Dev. Psychol. 1979, 15, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.; Hayden, B.Y. The psychology and neuroscience of curiosity. Neuron 2015, 88, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S.M.; Zelazo, P.D. Minnesota Executive Function Scale-Test Manual; Reflection Sciences: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zamzow, J.; Ernst, J. Supporting school readiness naturally: Investigating executive function growth in nature preschools. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2019. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, E.P. Administration, Scoring, and Norms Manual: Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement; Scholastic Testing Service: Bensenville, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Massillon Museum and Stark County ESC. Artful Living and Learning: Three Assessment Tests and the Results; Massillon Museum and Stark County ESC: Stark County, OH, USA, 2014. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED590201.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Wojciehowski, M.; Ernst, J. Creative by Nature: Investigating the Impact of Nature Preschools on Children’s Creative Thinking. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2018, 6, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, J.; Johnson, M.; Burcak, F. The nature and nurture of resilience: Exploring the impact of nature preschools on young children’s protective factors. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2019, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of the Child; General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20; Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 1989; Available online: www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm (accessed on 22 June 2006).

- Chawla, L.; Keena, K.; Pevec, I.; Stanley, E. Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almon, J. Resiliency: More than bouncing back. In Community Playthings Resources; Community Playthings: Ulster Park, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.communityplaythings.com/resources/articles/2015/resilience (accessed on 8 July 2015).

- Sobel, D. Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education; The Orion Society: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Adjusted Posttest M (Stnd. Error) 1 | Statistical Significance 3 of Pairwise Comparisons of Adj. Posttest Means | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toys Taken Out | Nature 2 | 8.38 (3.39) | 9.76 (2.86) | 9.61 (0.46) | p = 0.21 |

| Non-Nature 2 | 7.81 (4.19) | 8.73 (3.14) | 8.85 (0.40) | ||

| Toys Explored | Nature 2 | 6.44 (3.09) | 6.47 (3.56) | 6.05 (0.66) | p = 0.83 |

| Non-Nature 2 | 3.50 (2.71) | 5.91(3.65) | 6.24 (0.57) | ||

| Toys Engaged With | Nature 2 | 4.15 (2.60) | 7.62 (2.58) | 7.61 (0.48) | p = 0.01 ** |

| Non-Nature 2 | 4.23 (2.89) | 5.91(3.46) | 5.92 (0.42) |

| Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | Adjusted Posttest M (Stnd. Error) 1 | Statistical Significance of Pairwise Comparison of Adj. Posttest Means | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature 2 | 41.78 (14.89) | 51.46 (14.57) | 50.86 (1.29) | p = 0.60 |

| Non-Nature 2 | 38.54 (14.40) | 48.66 (14.99) | 49.72 (1.73) |

| Pretest Mean (SD) | Posttest Mean (SD) | Statitical Significance 2 of Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluency | |||

| Treatment (nature preschools) 1 | 89.89 (17.76) | 104.76 (28.35) | p = < 0.001 ** |

| Baseline (non-nature preschool) 1 | 97.55 (14.64) | 106.55 (22.88) | p = 0.22 |

| Originality | |||

| Treatment (nature preschools) 1 | 96.13 (20.16) | 113.61 (36.58) | p = < 0.001 ** |

| Baseline (non-nature preschool) 1 | 105.20 (14.13) | 126.00 (30.59) | p = 0.07 |

| Imagination | |||

| Treatment (nature preschools) 1 | 89.85 (17.68) | 99.99 (18.42) | p = < 0.001 ** |

| Baseline (non-nature preschool) 1 | 92.30 (16.52) | 103.00 (12.03) | p = 0.06 |

| Nature Preschool 1 Teacher Rating | Nature Preschool Parent Rating | Non-Nature Preschool 2 Teacher Rating | Non-Nature Preschool Parent Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest Mean (SD) | Posttest Mean (SD) | Pretest Mean (SD) | Posttest Mean (SD) | Pretest Mean (SD) | Posttest Mean (SD) | Pretest Mean (SD) | Posttest Mean (SD) | |

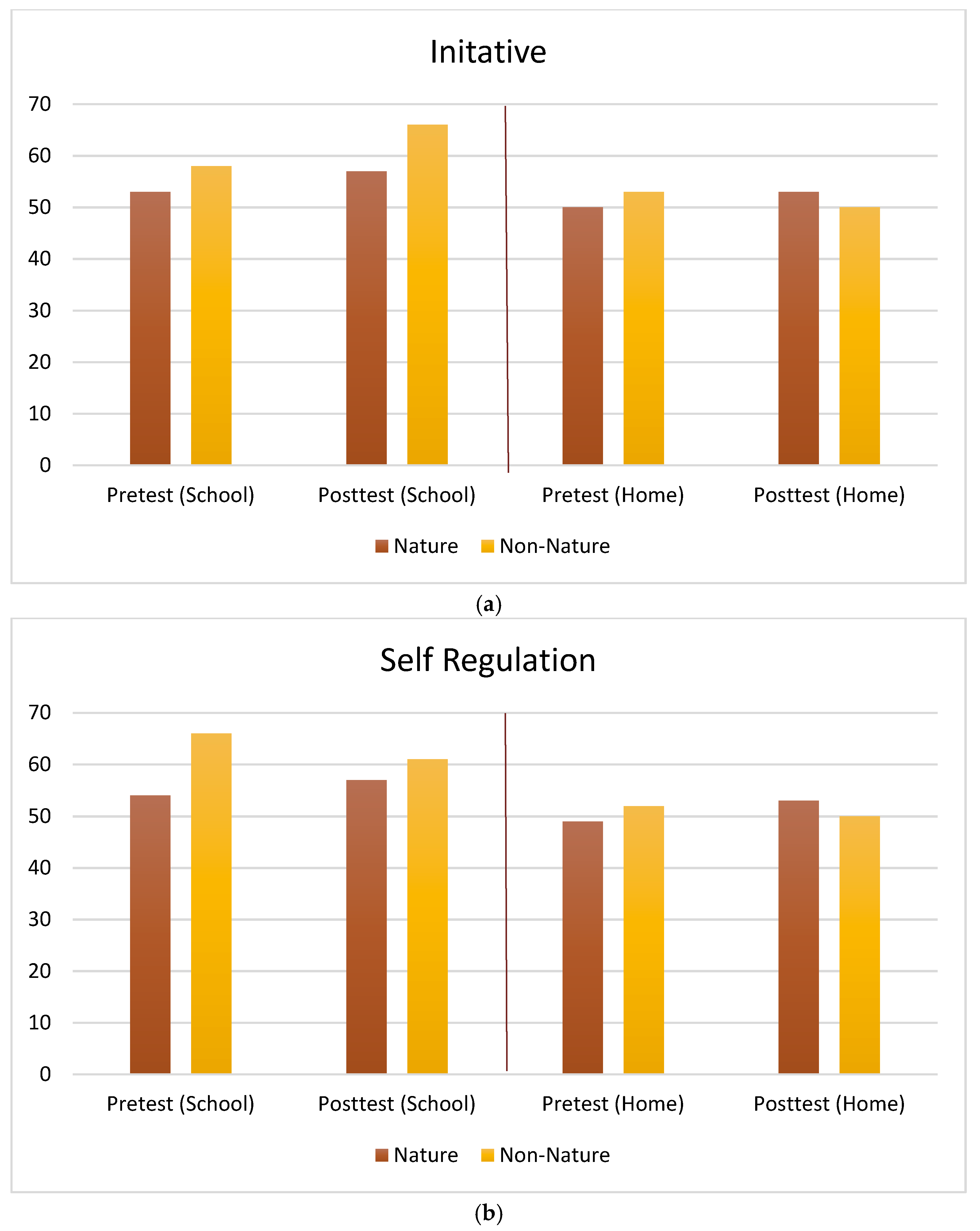

| Initiative | 52.74 (7.98) | 56.93 (8.55) ** | 49.84 (8.45) | 53.63 (8.17) ** | 57.93 (7.98) | 66.36 (5.62) ** | 53.21 (6.19) | 50.27 (8.60) |

| Self-Regulation | 54.49 (6.00) | 56.78 (8.05) ** | 49.31 (7.98) | 53.34 (9.34) ** | 66.36 (5.63) | 61.27 (5.08) | 51.71 (4.50) | 52.27 (9.12) |

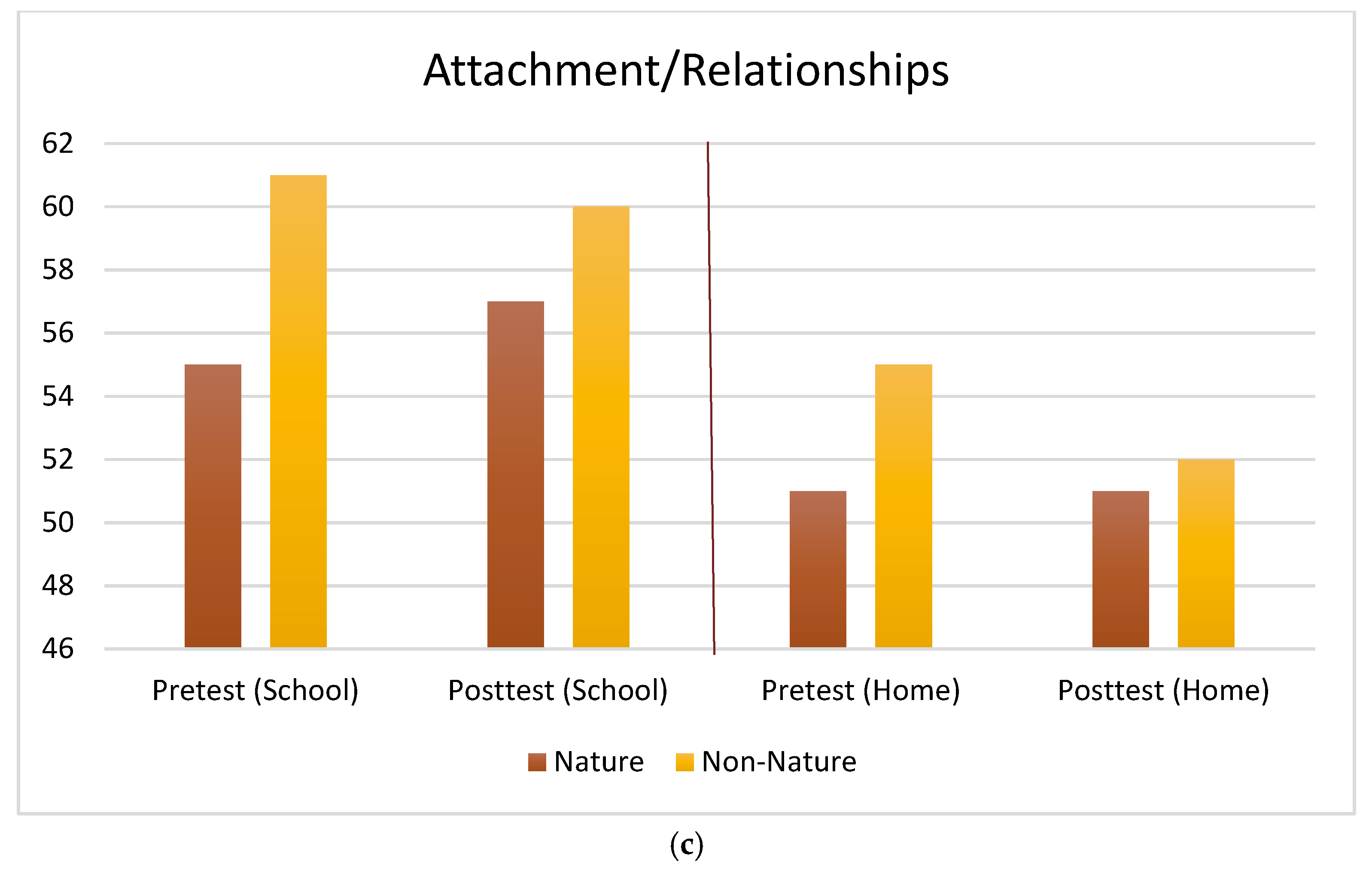

| Attachment | 55.26 (6.91) | 57.21 (7.45) | 51.64 (7.24) | 51.39 (9.93) | 61.27 (5.08) | 60.18 (5.09) | 54.57 (7.54) | 54.91 (7.26) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ernst, J.; Burcak, F. Young Children’s Contributions to Sustainability: The Influence of Nature Play on Curiosity, Executive Function Skills, Creative Thinking, and Resilience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154212

Ernst J, Burcak F. Young Children’s Contributions to Sustainability: The Influence of Nature Play on Curiosity, Executive Function Skills, Creative Thinking, and Resilience. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154212

Chicago/Turabian StyleErnst, Julie, and Firdevs Burcak. 2019. "Young Children’s Contributions to Sustainability: The Influence of Nature Play on Curiosity, Executive Function Skills, Creative Thinking, and Resilience" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154212

APA StyleErnst, J., & Burcak, F. (2019). Young Children’s Contributions to Sustainability: The Influence of Nature Play on Curiosity, Executive Function Skills, Creative Thinking, and Resilience. Sustainability, 11(15), 4212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154212