The Impact of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation on Sustainable Performance in Islamic Banks: A Mediation Analysis through a SEM Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Research Objectives and Questions

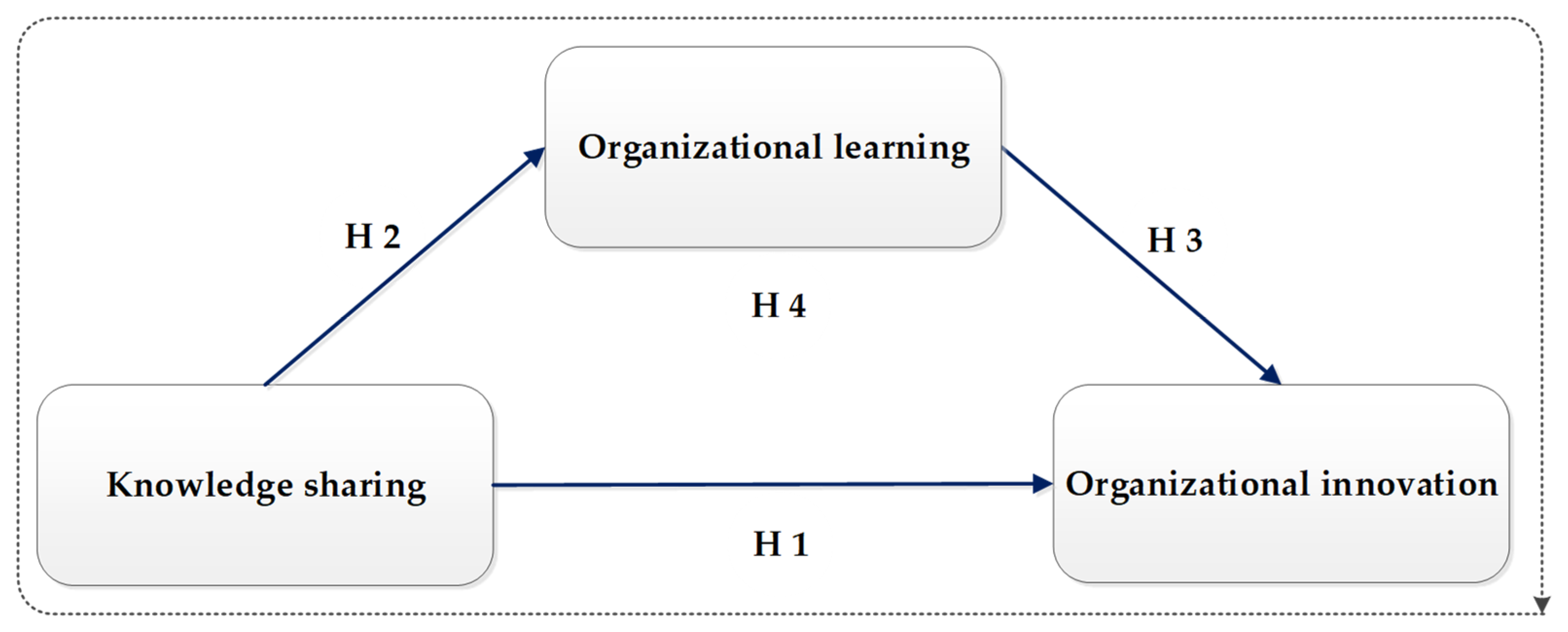

- To assess the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation in Pakistani Islamic banks;

- To assess the relationship between knowledge sharing and learning in Pakistani Islamic banks;

- To assess the relationship between learning and organizational innovation in Pakistani Islamic banks;

- To assess and test the mediating effect of learning on knowledge sharing and innovation in Pakistani Islamic banks.

2. Critical Literature Review and Hypothesis Building

2.1. The Linkage of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation in Pakistani Islamic Banks (KS and OI)

2.2. Linkage of Islamic Banks Knowledge Sharing and Organizational Learning (KS and OL)

2.3. Linkage of Islamic Banks/Organizational Learning and Innovation (OL and OI)

2.4. The Relationship among Learning, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovation (OL, KS, and OI) in Islamic Banks

2.5. Research Framework

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Research Instruments

3.2. Designing a Questionnaire

3.3. Sample Size—Target Population

3.4. Data Processing of the Questionnaires

3.5. Variable Measurement

3.5.1. Knowledge Sharing of Pakistani Islamic Banks

3.5.2. Organizational Innovation

3.5.3. Organizational Learning

3.5.4. Control Variables

3.6. Methods Used for Analyzing Data

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Evaluating the Measurement Model

4.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model

4.2.1. Analysis of the Study Model Showing a Direct Effect

4.2.2. Analysis of Total and Indirect Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Knowledge Sharing [76,77,78,79,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96] | VR | R | M | F | VF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS-1 | I expect to receive monetary rewards in return for my knowledge sharing. | |||||

| KS-2 | I expect to receive additional points for promotion in return for knowledge sharing. | |||||

| KS-3 | I expect to receive an honor such as educational opportunity in return for my knowledge sharing. | |||||

| KS-4 | My knowledge sharing would strengthen the tie between me and existing members in the bank. | |||||

| KS-5 | My knowledge sharing would get me well acquainted with new members in the bank. | |||||

| KS-6 | My knowledge sharing would expand the scope of my associations with other members in the bank. | |||||

| KS-7 | My knowledge sharing would draw smooth cooperation from members in future. | |||||

| KS-8 | My knowledge sharing would make strong relationships with members who have common interests in the bank. | |||||

| KS-9 | My knowledge sharing would help other members in bank to solve problems. | |||||

| KS-10 | My knowledge sharing would create new business opportunities for bank. | |||||

| KS-11 | My knowledge sharing would improve work processes in the bank. | |||||

| KS-12 | My knowledge sharing would increase the productivity in the bank. | |||||

| KS-13 | My knowledge sharing would help the bank to achieve its performance objectives. | |||||

| KS-14 | My knowledge sharing with other bank members is good. | |||||

| KS-15 | My knowledge sharing with other bank members is pleasant. | |||||

| KS-16 | My knowledge sharing with other bank members is valuable. | |||||

| KS-17 | My knowledge sharing with other bank members is wise. | |||||

| KS-18 | I will share my knowledge with more bank members. | |||||

| KS-19 | I will always provide my knowledge at request of other bank members. | |||||

| KS-20 | I intend to share my knowledge with other bank members frequently in future | |||||

| KS-21 | I try to share my knowledge with other organizational members in an effective way | |||||

| KS-22 | I will open my knowledge to anyone in the organization if it is helpful to the bank. |

| Items | Organizational Innovation [97,100,101,102] | MWC | WC | EC | SC | MSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OI-1 | Efforts to develop new products/services in terms of hours/person, teams and training involved. | |||||

| OI-2 | Pioneer disposition to introduce new products/services. | |||||

| OI-3 | Number of new products/services introduced. | |||||

| OI-4 | Efforts to develop new products/services in terms of hours/person, teams and training involved. | |||||

| OI-5 | Pioneer disposition to introduce new products/services. | |||||

| OI-6 | Number of new products/services introduced. | |||||

| OI-7 | Novelty of administrative systems. | |||||

| OI-8 | Search for new administrative systems by managers. | |||||

| OI-9 | Pioneer disposition to introduce new administrative systems |

| Items | Organizational Learning [103,104,105,106,108] | SD | D | N | A | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL-1 | The personnel often participate in shows and events. | |||||

| OL-2 | Our bank has a resourceful & consolidated research and development policy. | |||||

| OL-3 | Our bank test creative thoughts and tactics on workplace regularly. | |||||

| OL-4 | Our bank takes proper mechanisms to ensure the distribution of the best practices between the diverse fields of the activity. | |||||

| OL-5 | Some people in the bank participate in different divisions or teams, and they perform as connections among them. | |||||

| OL-6 | All employees of our bank convey the similar goal to which they sense dedicated. | |||||

| OL-7 | Workers exchange experiences and knowledge through mutual conversion. | |||||

| OL-8 | Our bank usually practices and encourage teamwork. | |||||

| OL-9 | Our bank has a complete record of employees/experts with respect to their area of specialization. If anyone needs, he/she can find at any time. | |||||

| OL-10 | Our bank has a complete database of its customers. | |||||

| OL-11 | All the employees are having access to bank’s databases and records. |

References

- Tavakoli, I.; Lawton, J. Strategic thinking and knowledge management. In Handbook of Business Strategy; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2005; Volume 6, pp. 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, J.A. Knowledge Management as a Strategic Asset: An Integrated, Historical Approach; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mizintseva, M.F.; Gerbina, T.V. Knowledge Management: A Tool for Implementing the Digital Economy. In Scientific and Technical Information Processing; Pleiades Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 45, pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.M.; Ahmad, N.H. Nor Hayati Knowledge management in Malaysian bank: A new paradigm. J. Knowl. Manag. Pract. 2006, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.-G.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Fernández-Gil, J.-R. Improving customer capital through relationship memory at a commercial bank in Spain. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2014, 12, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barachini, F. Cultural and social issues for knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Busso, D.; Kamboj, S. Top management knowledge value, knowledge sharing practices, open innovation and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 39, 8899–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongurai, J.; Vithessonthi, C. The impact of the banking sector on economic structure and growth. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2018, 56, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.D.; Connolly, D.J. Experience-based travel: How technology is changing the hospitality industry. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2000, 41, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, C.S.; Awan, S.H.; Naveed, S.; Ismail, K. A comparative study of the application of systems thinking in achieving organizational effectiveness in Malaysian and Pakistani banks. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Aliyu, S. A contemporary survey of islamic banking literature. J. Financ. Stab. 2018, 34, 12–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Nawaz, H. Islamic financial system and conventional banking: A comparison. Arab Econ. Bus. J. 2018, 13, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Phan, D.H.B. A survey of Islamic banking and finance literature: Issues, challenges and future directions. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2019, 53, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontot, K.; Hamali, J.; Abdullah, F. Determining Factors of Customers’ Preferences: A Case of Deposit Products in Islamic Banking. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, U.; Burton, B.; Monk, L. Perceptions on the accessibility of Islamic banking in the UK—Challenges, opportunities and divergence in opinion. Account. Forum 2017, 41, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore Jain, K.; Sandhu, M.S.; Wai Ling, C. Knowledge sharing in an American multinational company based in Malaysia. J. Workplace Learn. 2009, 21, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, Z. Collective Creativity for Responsible and Sustainable Business Practice; IGI Global: Dauphin, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ciulli, F.; Kolk, A. Incumbents and business model innovation for the sharing economy: Implications for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, I.; Faems, D.; De Faria, P. Coopetition and product innovation performance: The role of internal knowledge sharing mechanisms and formal knowledge protection mechanisms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 53, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, H.d.J.G.; Pinheiro, P.G. Linking knowledge management, organizational learning and memory. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2444569X19300319 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Huang, J.C.; Newell, S. Knowledge integration processes and dynamics within the context of cross-functional projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudon, K.C.; Laudon, J.P. Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm, Student Value Edition Plus Mymislab with Pearson Etext—Access Card Package; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, H.; Villamor, I.; Aguinis, H. Innovation leadership: Best-practice recommendations for promoting employee creativity, voice, and knowledge sharing. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Mirakhor, A. Ethical Dimensions of Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F. Islamic Banking in Pakistan: Shariah-Compliant Finance and the Quest to Make Pakistan More Islamic; Taylor & Francis Group: Didcot, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C.H.; Henry, C.M.; Wilson, R. The Politics of Islamic Finance; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton, R.; Darroch, J. Beyond market orientation: Knowledge management and the innovativeness of New Zealand firms. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 572–593. [Google Scholar]

- Mardani, A.; Nikoosokhan, S.; Moradi, M.; Doustar, M. The Relationship Between Knowledge Management and Innovation Performance. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2018, 29, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nicolás, C.; Meroño-Cerdán, Á.L. Strategic knowledge management, innovation and performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, H.-C.; Chang, J.-C. The role of organizational learning in transformational leadership and organizational innovation. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2011, 12, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Management Association, I.R. Organizational Culture and Behavior: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Dauphin, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.; Dalkir, K.; Bidian, C. A holistic view of the knowledge life cycle: The knowledge management cycle (KMC) model. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 12, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Seleim Ahmed, A.S. Understanding the knowledge management-intellectual capital relationship: A two-way analysis. J. Intellect. Cap. 2011, 12, 586–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitić, S.; Nikolić, M.; Jankov, J.; Vukonjanski, J.; Terek, E. The impact of information technologies on communication satisfaction and organizational learning in companies in Serbia. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.S.; Adya, M. Knowledge sharing and the psychological contract. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Husted, K.; Michailova, S. Governing Knowledge Sharing in Organizations: Levels of Analysis, Governance Mechanisms, and Research Directions. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengmeng, Z.; Yamin, Z.; Zhiwei, Z.; Xiaomin, G. Research on Intensive Facts about Explicit Case of Tacit Knowledge. Procedia Eng. 2017, 174, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharo, M.; Gregg, D.; Ramirez, R. Virtual team effectiveness: The role of knowledge sharing and trust. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, J.C. Organizational knowledge, learning and memory: Three concepts in search of a theory. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1996, 9, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, J.C. Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adloff, F.; Gerund, K.; Kaldewey, D. Revealing Tacit Knowledge: Embodiment and Explication; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Jung, J.E. SocioScope: A framework for understanding Internet of Social Knowledge. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 83, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, M.A. Knowledge Management and Competitive Advantage: Issues and Potential Solutions: Issues and Potential Solutions; IGI Global: Dauphin, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.T.; Azam, N.; Khalid, S.; Yao, J. A three-way approach for learning rules in automatic knowledge-based topic models. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2017, 82, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Higginson, J.; Oborne, C.A.; Thomas, R.E.; Ramsay, A.I.; Fulop, N.J. Codifying knowledge to improve patient safety: A qualitative study of practice-based interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 113, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machacek, E.; Hess, M. Whither ‘high-tech’ labor? Codification and (de-)skilling in automotive components value chains. Geoforum 2017, 99, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabitza, F.; Ciucci, D.; Locoro, A. Exploiting collective knowledge with three-way decision theory: Cases from the questionnaire-based research. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2017, 83, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.T. The impact of knowledge sharing on organizational learning and effectiveness. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibella, A.J.; Nevis, E.C.; Gould, J.M. Understanding Organizational Learning Capability. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J.; Scarbrough, H.; Robertson, M. The Construction of ‘Communities of Practice’ in the Management of Innovation. Manag. Learn. 2002, 33, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtka, J. Linking Competitive Advantage with Communities of Practice. J. Manag. Inq. 1999, 8, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, G.L. Handbook of Research on Information Architecture and Management in Modern Organizations; IGI Global: Dauphin, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N.B.; Moesel, D.D.; Herschel, R.T. Using “knowledge champions” to facilitate knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manag. 2003, 7, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; García-Morales, V.J.; Cordón-Pozo, E. Leadership and organizational learning’s role on innovation and performance: Lessons from Spain. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M.M.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. Transformational leadership influence on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H. Creating competitive advantage: Linking perspectives of organization learning, innovation behavior and intellectual capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Vijande, M.L.; Sanzo-Perez, M.J.; Alvarez-Gonzalez, L.I.; Vazquez-Casielles, R. Organizational learning and market orientation: Interface and effects on performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2005, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.F.; Hult, G.T.M. Innovation, Market Orientation, and Organizational Learning: An Integration and Empirical Examination. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hurley, R.F.; Knight, G.A. Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İpek, İ. Organizational learning in exporting: A bibliometric analysis and critical review of the empirical research. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, L.; Zeng, S. Inter-organizational knowledge acquisition and firms’ radical innovation: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijande, M.L.S.; Sánchez, J.Á.L. The Effects of Organizational Learning on Innovation and Performance in Kibs: An Empirical Examination. in The Customer is NOT Always Right? In Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, M.L.; Chien, I. Rethinking organizational learning orientation on radical and incremental innovation in high-tech firms. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2302–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Van Niekerk, M.; de Martino, M. Knowledge Transfer To and Within Tourism: Academic, Industry and Government Bridges; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H. Role of restaurant employees’ intrinsic motivations on knowledge management: An application of need theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2751–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.E. Transferring Tourism Knowledge. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 7, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaol, F.L.; Hutagalung, F. The Role of Service in the Tourism & Hospitality Industry. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on Management and Technology in Knowledge, Service, Tourism & Hospitality 2014 (SERVE 2014), Gran Melia, Jakarta, Indonesia, 23–24 August 2014; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. The Study of Knowledge Sharing Willingness of Employees of International Tourism Hotel Industry in Taichung. Unpublished. Master Thesis, Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung, Taiwan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holste, J.S. Trust and tacit knowledge sharing and use. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas Leyland, M. The role of teams, culture, and capacity in the transfer of organizational practices. Learn. Organ. 2010, 17, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Consumer perception of knowledge-sharing in travel-related Online Social Networks. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-T.; Hou, Y.-P. Motivations of employees’ knowledge sharing behaviors: A self-determination perspective. Inf. Organ. 2015, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.P.; Stawarski, C.A. Data Collection: Planning for and Collecting All Types of Data; Wiley: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, G.-W.; Kim, Y.-G. Breaking the Myths of Rewards: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes about Knowledge Sharing. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2002, 15, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauch, L.R. Tailoring Incentives for Researchers. Res. Manag. 2016, 19, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Balkin, D.B.; Milkovich, G.T. Rethinking rewards for technical employees. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, J.W. Three Other R’s: Recognition, Reward and Resentment. Res. Technol. Manag. 1993, 36, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Y.; Galletta, D.F. Extending the technology acceptance model to account for social influence: Theoretical bases and empirical validation. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences 1999, HICSS-32, Abstracts and CD-ROM of Full Papers, Maui, HI, USA, 5–8 January 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deluga, R.J. Leader-member exchange quality and effectiveness ratings: The role of subordinate-supervisor conscientiousness similarity. Group Organ. Manag. 1998, 23, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrowe, R.T.; Liden, R.C. Process and Structure in Leader-Member Exchange. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 522–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seers, A.; Petty, M.M.; Cashman, J.F. Team-Member Exchange Under Team and Traditional Management. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 20, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.A.; Kozlowski, S.W.; Chao, G.T.; Gardner, P.D. A longitudinal investigation of newcomer expectations, early socialization outcomes, and the moderating effects of role development factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhe, A. Strategic Alliance Structuring: A Game Theoretic and Transaction Cost Examination of Interfirm Cooperation. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 794–829. [Google Scholar]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Social cognitive theory and self-efficacy: Goin beyond traditional motivational and behavioral approaches. Organ. Dyn. 1998, 26, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G.; Pierce, J.L. Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy within the Organizational Context. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 23, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Merritt, D.E. Divergent Effects Of Job Control On Coping With Work Stressors: The Key Role Of Self-Efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 738–754. [Google Scholar]

- Gecas, V.; Schwalbe, M.L. Parental Behavior and Adolescent Self-Esteem. J. Marriage Fam. 1986, 48, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. On construct validity: A critique of Miniard and Cohen’s paper. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 17, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.P.; Shaver, P.R. Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.L. Handbook of Organizational Measurement. Int. J. Manpow. 1997, 18, 305–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J.; Maltz, E.; Jaworski, B.J. Enhancing Communication between Marketing and Engineering: The Moderating Role of Relative Functional Identification. J. Mark. 2018, 61, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darroch, J.; McNaughton, R. Beyond market orientation. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manis, J.G.; Meltzer, B.N. A Reader in Social Psychology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Heide, J.B.; Miner, A.S. The Shadow of the Future: Effects of Anticipated Interaction and Frequency of Contact on Buyer-Seller Cooperation. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, F.A. Innovation Orientation, Environment and Performance: A Comparison of U.S. and European Markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1992, 23, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K. Resolving the Capability–Rigidity Paradox in New Product Innovation. J. Mark. 2018, 69, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Cummings, A. Employee Creativity: Personal and Contextual Factors at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, R.W.; Sawyer, J.E.; Griffin, R.W. Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Hoskisson, R.E.; Kim, H. International Diversification: Effects on Innovation and Firm Performance in Product-Diversified Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 767–798. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, D.; Slocum, J.W.; Pitts, R.A. Designing organizations for competitive advantage: The power of unlearning and learning. Organ. Dyn. 1999, 27, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Product-market Strategy and Performance: An Analysis of the Miles and Snow Strategy Types. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. The Synergistic Effect of Market Orientation and Learning Orientation on Organizational Performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez-Gómez, P.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.; Valle-Cabrera, R. Organizational learning capability: A proposal of measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippins, M.J.; Sohi, R.S. IT competency and firm performance: Is organizational learning a missing link? Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez López, S.; Manuel Montes Peón, J.; José Vázquez Ordás, C. Managing knowledge: The link between culture and organizational learning. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 2018, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, N.M. The Organizational Learning Cycle: How We Can Learn Collectively; Taylor & Francis: Didcot, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Titi Amayah, A. Determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector organization. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Raza, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Minai, M.S.; Bano, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Business Networks on Firms’ Performance Through a Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, H.; Raza, M.A.; Ali, G.; Aman, J.; Nurunnabi, M. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices and Environmental Factors through a Moderating Role of Social Media Marketing on Sustainable Performance of Business Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, J.; Duan, W. Social media and firm equity value. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Aqeel, M.; Abbas, J.; Shaher, B.; Jaffar, A.; Sundas, J.; Zhang, W. The moderating role of social support for marital adjustment, depression, anxiety, and stress: Evidence from Pakistani working and nonworking women. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 244, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Aman, J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The Impact of Social Media on Learning Behavior for Sustainable Education: Evidence of Students from Selected Universities in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Abbas, J.; Wenhong, Z.; Akhtar, T.; Aqeel, M. Linking infidelity stress, anxiety and depression: Evidence from Pakistan married couples and divorced individuals. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2018, 11, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Aqeel, M.; Wenhong, Z.; Aman, J.; Zahra, F. The moderating role of gender inequality and age among emotional intelligence, homesickness and development of mood swings in university students. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2018, 11, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.N.; Xiuchun, B.; Abbas, J.; Shuguang, Z. Analyzing predictors of customer satisfaction and assessment of retail banking problems in Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1338842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.T.; Abbas, J.; Lei, S.; Jamal Haider, M.; Akram, T. Transactional leadership and organizational creativity: Examining the mediating role of knowledge sharing behavior. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311975.2017.1361663 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Aman, J.; Abbas, J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The Relationship of Religiosity and Marital Satisfaction: The Role of Religious Commitment and Practices on Marital Satisfaction Among Pakistani Respondents. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, T.; Abbas, J.; Wei, Z.; Nurunnabi, M. The Effect of Sustainable Urban Planning and Slum Disamenity on The Value of Neighboring Residential Property: Application of The Hedonic Pricing Model in Rent Price Appraisal. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, J.; Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The Influence of Islamic Religiosity on the Perceived Socio-Cultural Impact of Sustainable Tourism Development in Pakistan: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency (f) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 232 | 80.8 |

| Female | 55 | 19.2 |

| Experience | ||

| 1–5 years | 95 | 33.1 |

| 6–10 | 78 | 27.1 |

| 11–15 | 63 | 22.0 |

| >15 | 51 | 17.8 |

| Age | ||

| 21–30 years | 69 | 24.0 |

| 31–40 | 123 | 42.9 |

| 41–50 | 57 | 19.9 |

| >50 | 38 | 13.2 |

| Education | ||

| Intermediate | 23 | 8.0 |

| Graduation | 119 | 41.5 |

| Masters | 145 | 50.5 |

| Total | 287 | 100 |

| Construct | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Expected rewards | One’s belief that he/she will have rewards after sharing his/her knowledge with others. | [76,77,78,79] |

| Expected associations | One’s belief that after sharing knowledge, his/her ties with other employees will strengthen. | [80,81,82,83,84] |

| Expected contribution | One’s belief that after sharing his/her knowledge, the overall performance of the firm will increase. | [85,86,87,88] |

| Attitude toward KS | Level of someone’s pleasant emotions after sharing his/her knowledge | [89,90,91,92] |

| Knowledge sharing behavior | Level of knowledge shared by someone. | [93,94,95,96] |

| Construct | Definition of the Construct | References |

|---|---|---|

| Product innovation | Product innovation is the outcome of processes involving time, individuals, teams and training to develop and offer new products or services. It refers to a tendency to introduce new products or services. | [97,98,99,100,101] |

| Process innovation | The innovation process requires numerous changes. It also refers to the tendency to introduce new products or services. The innovation process demands a quick reaction to new procedures introduced by competitors in the market. | [97,98,99,100,102] |

| Administrative Innovation | Administrative innovation refers to the novelty within the systems of the organizations. Managers look for new and useful administrative systems. It also relates to a tendency to introduce new administrative systems. | [97,98,99,101] |

| Construct | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Acquiring Knowledge | The personnel often participate in shows and events to gain knowledge. Our firm has an original and consolidated research and development policy. The firm regarly tests creative thoughts and tactics in the workplace. | [105,106,108] |

| Distributing Knowledge | This firm takes proper actions to ensure the distribution of the best practices between diverse activities. Some people in the firm participate in different divisions or teams, and they perform as connections among them. Some personnel have the responsibility of gathering, accumulating, and disseminating workers’ recommendations. | [104,105,106,108] |

| Interpreting Knowledge | All employees of our firm convey a similar goal to which they are dedicated. Workers exchange experiences and knowledge through mutual conversions. Our firm usually practices and encourages teamwork. | [103,106,108] |

| Organizational Memory | This firm has a complete record of employees/experts concerning their area of specialization. If anyone needs to, he/she can find it at any time. Our firm has a complete database of its customers. All employees have access to the business firm’s databases and records. The firm updates the databases regularly. | [103,104,106,107,108] |

| Construct | Mean | SD | Item | Loading | AVE | CR | Cα |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KS | 3.58 | 0.52 | KS-1 | 0.73 *** | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| KS-2 | 0.95 *** | ||||||

| KS-3 | 0.68 *** | ||||||

| KS-4 | 0.99 *** | ||||||

| KS-5 | 0.78 *** | ||||||

| OI | 3.72 | 0.60 | OI-1 | 0.88 *** | 0.79 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| OI-2 | 0.85 *** | ||||||

| OI-3 | 0.92 ** | ||||||

| OL | 3.52 | 0.50 | OL-1 | 0.76 *** | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| OL-2 | 0.77 *** | ||||||

| OL-3 | 0.67 *** | ||||||

| OL-4 | 0.75 *** |

| Construct | KS | OI | OL | RG | RE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge sharing | 0.74 | ||||

| Organizational innovation | 0.49 | 0.84 | |||

| Organizational learning | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.79 | ||

| Gender | –0.14 | –0.01 | –0.33 | 1 | |

| Education | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 1 |

| Fit Index | Score | Recommended Threshold Value |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Fit Measures | ||

| CMIN/df | 1.549 | ≤2 a; ≤5 b |

| GFI | 0.894 | ≥0.90 a; ≥0.80 b |

| RMSEA | 0.040 | ≤0.80 a; ≤0.10 b |

| Incremental Fit Measures | ||

| NFI | 0.920 | ≥0.90 a |

| AGFI | 0.869 | ≥0.90 a; ≥0.80 b |

| CFI | 0.974 | ≥0.90 a |

| Parsimonious Fit Measures | ||

| PGFI | 0.727 | Greater is good |

| PNFI | 0.803 | Greater is good |

| Hypothesis | Relationships | Proposed Effect | Estimates | p | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | KS–OI | + | 0.732 *** | <0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | KS–OL | + | 0.565 *** | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | OL–OI | + | 0.226*** | <0.001 | Supported |

| H4 | KS–OL–OI | + | 0.129 *** | <0.001 | Supported |

| (C/V) | Gender–OI | + | –0.035 | 0.358 | Not supported |

| (C/V) | Education–OI | + | 0.187 *** | <0.001 | Supported |

| Dependent Factor/Predictor | OL | OI | KS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||

| OI | 0.565 | 0.732 | 0.275 |

| OL | 0.129 | ||

| Total effect—OI | 0.683 | ||

| Indirect effect—OI | 0.408 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, J.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, S.; Akram, S.; Shaheen, I.; Niu, B. The Impact of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation on Sustainable Performance in Islamic Banks: A Mediation Analysis through a SEM Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154049

Abbas J, Hussain I, Hussain S, Akram S, Shaheen I, Niu B. The Impact of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation on Sustainable Performance in Islamic Banks: A Mediation Analysis through a SEM Approach. Sustainability. 2019; 11(15):4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154049

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Jaffar, Iftikhar Hussain, Safdar Hussain, Sabahat Akram, Imrab Shaheen, and Ben Niu. 2019. "The Impact of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation on Sustainable Performance in Islamic Banks: A Mediation Analysis through a SEM Approach" Sustainability 11, no. 15: 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154049

APA StyleAbbas, J., Hussain, I., Hussain, S., Akram, S., Shaheen, I., & Niu, B. (2019). The Impact of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation on Sustainable Performance in Islamic Banks: A Mediation Analysis through a SEM Approach. Sustainability, 11(15), 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154049