Abstract

Many paramedics are working under levels of fatigue that would warrant immediate removal from the workplaces in other industries and such high levels of fatigue indicate a work system that is not sustainable. Sustainable work systems (SWS) build on a sociotechnical systems approach to work redesign. To diagnose the key issues in a work system, and inform any redesign or interventions, a powerful diagnostic tool, such as convergent interviewing, may be helpful. Convergent interviewing was applied to a paramedic context, extending the standard sociotechnical systems approach to work and non-work systems. The inductive convergent interviewing process was able to encapsulate the complexity of the key issues associated with fatigue and recovery in the system that is the paramedics’ lives. The issues raised could then be used to inform system changes in a move toward more sustainable work practices for paramedics.

1. Introduction

To be sustainable, work systems need to deploy their resources, including human resources, in such a manner that the resources can be regenerated by the system. The sustainability of employment relationships is particularly a concern in health services, a sector facing high levels of fatigue and other indicators of poor employee health. Fatigue can be defined as “a biological drive for recuperative rest”, where “fatigue may take several forms, including sleepiness, as well as mental, physical, and/or muscular fatigue depending on the nature of its cause”, where sleepiness and mental fatigue may be the most important forms of fatigue [1].

The levels of fatigue among a sample of paramedics in the United States of America (US) were so high that nearly six percent [2] were above a standard where commercial motor vehicle drivers would have been immediately taken off the job for evaluation [3], and as many as 10% of a sample of Dutch paramedics reported a level of fatigue that put them at risk of taking sick leave or work disability [4]. More generally, studies have found that relatively large proportions of the paramedic workforce have substantial daytime sleepiness (e.g., 36% in the US [2]), or experienced sleep problems (e.g., 30% in Sweden [5]).

The work system of these paramedics is not sustainable. Changing our orientation from focusing on work-intensity, to developing the regenerative capabilities of the system, will help make work systems more sustainable [6]. To move towards developing sustainable work systems (SWS) will require incorporating regenerative elements into our consideration, as well as the use of tools that can handle the complexity of the situation and a holistic consideration of the system. For example, incorporating regenerative elements in terms of content is demonstrated by a move from, intensity-oriented work system indicators (e.g., fatigue) to sustainable work system elements, such as the relationships in the system between fatigue and recovery. The potential of enhanced sustainability is demonstrated when emergency workers are able to recover from fatigue and their performance improves [7]. The following section reviews the complexity of the paramedic work situation, linking the key fatigue issues in work systems to an existing model of work from outside SWS including the regenerative elements of recovery. Then, the paper will review the systems-oriented nature of SWS, particularly how SWS builds on the work of sociotechnical systems.

1.1. Moving Consideration of Complex Work Systems to A More Regenerative Framework

Paramedics, also referred to as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) in some countries, do work involving stressful conditions, variable workloads, life or death decision making, complex interpersonal interactions under severe time constraints, as well as the stress of the circadian disruption arising from their shifts [2]. That is, paramedic work is complex, containing many possible stressors and causes of fatigue. To create and manage a sustainable work system where the human and social resources of the system are regenerated [6] for paramedics requires an understanding of these complicated inter-relationships among the key social, technical, and environmental issues at each level of the system and across levels of the system.

An initial set of issues could be derived from existing models of work. Stress oriented models such as the Demand-Control-Support (DCS) model represent a range of factors impacting on strain and those factors can be augmented to customize the DCS model to a particular context [8,9], but to be sustainable, models of work systems need to include recovery, and strive for a balance between work and recovery, an approach that is represented by the Effort-Recovery (E-R) model [10].

Experiencing high job demands (e.g., work overload and responsibility) requires effort that is associated with strain (e.g., acute fatigue) and the consequent symptoms as represented by the E-R model of stress [10]. There are many possible causes of effort and strain and many of those causes have varying impacts. For example, fatigue can be the result of many individual (e.g., age, circadian rhythm) and work system factors, such as repetitive tasks, shift work, and night time work [11]. Shift-work alone can be a chronic stressor that negatively impacts sleep and other aspects of health [12].

Though the impacts of shiftwork can vary, a key mechanism for the impact of shiftwork on workers is through the disruption of the body’s circadian rhythm [13], which can result in chronic changes in physiological homeostasis or the disruption and desynchronization of circadian rhythms [14]. Night shifts have the largest circadian disruption, and health services workers working night shift have generally reported poorer health outcomes than day workers, though these effects have sometimes been found to vary by age [15]. Another influencing factor is the degree of autonomy over shiftwork scheduling, particularly in terms of the extent to which shiftwork can be aligned with family life [11].

Many of the key workplace issues impacting fatigue have multiple relationships with fatigue. Variables such as job demands affect workplace perceptions over and above the effect of shift [16]. However, the variability and continuity of demands may also impact fatigue, especially for paramedics.

Paramedic work can entail a combination of sedentary time, while waiting for a callout, followed by bursts of high demands when responding to a call [17]. The continuity of demands can be exacerbated when hospitals do not accept the quick transfer of medium acuity patients with symptoms, such that they cannot be transferred to the waiting room area of the Emergency Department and remain on the ambulance stretcher, resulting in paramedics waiting longer with the patient—a situation known as ‘ramping’ [18]. That is, demands can vary by patient acuity or be prolonged with no down-time, and/or be highly variable. Conversely, demands may not be a direct driver of strain outcomes in some situations at all, with protective factors, such as social support having a benefit and demands having no impact [19]. The availability of social support from colleagues, supervisors and outside work can impact paramedics’ sleep and lessen the impact of the stress of their work by facilitating more adaptive coping responses, or reducing rumination [20].

Most research on fatigue among paramedics or other health service workers has focused on the negative effects of stressors on health. However, the process of recovering from stressors is critical to regenerating the resources in a sustainable system and is increasingly getting attention, where either, the presence of recovery can be beneficial, or the lack of recovery can explain why work stressors translate into poor well-being and health problems [21]. Periods of rest and vacations can result in a decrease in perceived job stress and the recovery process that occurs during breaks from employment helps to ameliorate negative experiences at work [22]. Work breaks, non-work time during the evening or during the weekend, and vacations offer opportunities for such recovery processes and the restoration of threatened or lost resources, where the recovery process leads to reduced fatigue [23]. That is, life outside of work has an impact on how one feels and behaves at work [24]. However, for recovery effects to occur, not only the amount of time but other features of the activities (e.g., detachment, pleasantness) may be important [23].

Fatigue management approaches generally span multiple levels and offer increased flexibility in addressing risks, especially in shiftwork-based industries such as health services [11]. Further, expanding considerations of fatigue to include recovery may be critical with recovery potentially representing processes that could reverse health complaints, or prevent irreversible health complaints [21]. To better understand the variety of sources of fatigue and potential mechanisms of recovery requires an approach that reflects the complexity of the issues at, and sometimes across, varying levels of a system. A sociotechnical systems approach has previously been applied to better understand and address factors contributing to, and/or preventing, fatigue within hospital nurse work systems [11], and the systems analyses underpinning sociotechnical systems could be applied to paramedic work in order to make that system more sustainable.

1.2. The Systems-Oriented Nature of SWS

A sustainable work system is a system where human and social resources are regenerated through the process of work while still maintaining productivity and a competitive edge [6]. SWS has strong roots in the field of sociotechnical systems design and action research [25]. Sociotechnical systems approaches can be applied to help analyze and design sustainable work systems and typically consider relevant social, technical, and environmental variables and their interactions within each level of the system and across levels of the system [26].

The sociotechnical systems approach considers issues from the level of the individual, to the group/unit, the organization, the industry, and nation (e.g., see Figure 1 in [27], which is a modified excerpt from [28]). Analyses of sociotechnical systems are multi-level and nested in nature.

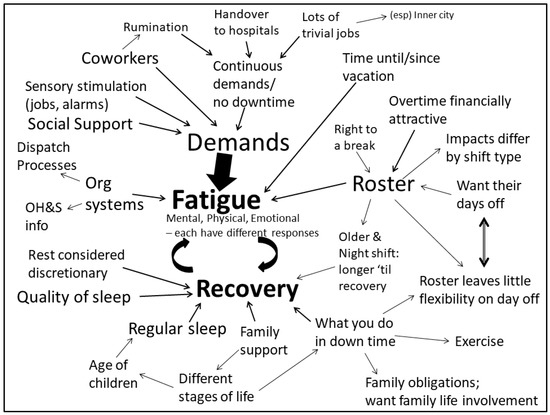

Figure 1.

Summary influence diagram of the key, common issues associated with paramedic fatigue and recovery.

Sociotechnical systems and SWS approaches to understanding paramedic fatigue and recovery need to reflect the relationships between and among levels, reveal cross-level interactions and can inform the design of improvements or interventions. For example, in a study of hospitals, a sociotechnical systems model enabled the testing of cross-level causal relationships between government targets, aimed at reducing bed occupancy, and the pressure placed upon managers and clinical staff to discharge patients, prioritizing finances over care delivery [29]. A sociotechnical systems approach enables analyses of issues from various levels of a system and can inform redesign activities in moving a system, such as that of paramedics, toward more sustainable systems of work.

The wide variety of potential causes of paramedic fatigue and recovery reviewed in the previous section and the systems-oriented nature of SWS highlight how an analysis of those potential causes requires a systems model that can summarize the issues occurring at different levels that sometimes operate across levels in paramedics’ lives.

Change processes for SWS design may be slightly more open than sociotechnical systems approaches. SWS relies on powerful and rich approaches to the preliminary analysis of the system to understand the organization and its environment [25], an approach similar to the initial diagnostic stages of some ergonomic models (e.g., to help pare-down the first stage of the “IDEAS” intervention framework of [30]), where accurate and effective diagnostics can greatly enhance the later SWS-oriented work.

This paper proposes that convergent interviews are a useful and powerful diagnostic tool for the critical initial analysis of the system that generates results highlighting the key issues and their inter-relationships [31]. Convergent interviews embody an action-oriented approach in the tradition of [31], and have been used for a variety of organizational development interventions [32]. Consequently, this study will apply convergent interviewing as an action research technique to inform the development of a SWS approach.

2. Materials and Methods

The focal sample of paramedics are from a state public health sector entity in Australia employing approximately 4000 employees including approximately 3300 clinical staff serving a population of approximately 6.5 million people. Australian paramedics have high rates of psychological injury such as stress, depression and fatigue. Overall, the rate of accepted injury claims for paramedics is as much as seven times the rate of non-health workers [33]. The paramedic work system is not sustainable.

Convergent interviewing is an inductive qualitative research method based on [32], that can surface and organize information, while maintaining the relevant context from each of the nested levels within a systems perspective. Convergent interviewing is a rigorous qualitative method for both consulting and academic projects [34], as well as for informing pragmatic change [35]. The method and its considerations are detailed in [32], with a more recent guide summarizing the main points [36]. The text in this section will summarize the main activities that were conducted as part of the convergent interviewing.

A steering committee of experienced professionals from across relevant sub-sectors of the health services industry finalized the main question and informed the choice of interviewees and their sequence, applying [32]. The focus of the interviews was the question: ‘What do you think are the contributing factors of fatigue and subsequent recovery of paramedics?’ This starting question and the probe questions that arose from later rounds were asked of the participants, applying the processes of [32]. Sixteen convergent interviews over eight rounds were conducted with experts in the fatigue of paramedics.

Convergent interviews typically have two interviews per round (per the key method text [32]), especially for problems that are specific and usually of the scope of an organization or a division within an organization. Convergent interviewing projects have been adapted to have three interviews per round where the scope of the problem being studied is wider than that of an organization, such as studies of a problem covering an entire industry. Our study was effectively within one organization, where the problem being studied was applicable to staff with patient contact of an ambulance service.

Note that, as in [32], the sequence of interviewees being interviewed was on the basis of their degree of expertise on the specific question of interest and the degree to which their knowledge was different to the other subject matter expert interviewees. That is, interviewees were not selected to be representative of the organization, nor as a function of their general expertise. The interviewees in the first few rounds had 25 years or more of experience and included people in management, as well as clinical roles, but they were selected because of their specific expertise on fatigue and recovery among paramedics.

Convergent interviews focus on the issues raised in the interviews, not the interviewees. There were two interviews in each round and after every round the content of the interviews was analyzed for issues in common. If both interviewees in a round raised an issue and agreed about the issue’s effects on fatigue and/or recovery, the researchers generated probe questions to tease out possible exceptions to that agreed relationship. If a round’s interviewees raised an issue but disagreed about its’ nature, the researchers generated a probe question to explore the differences. For example, if both interviewees in a round commented on staff struggling over winter, the researcher could generate a probe question for later rounds that asked about why is it more difficult to work and recover in winter than during the warmer months. The interviewees then clarified that it was more that night shifts over winter were difficult, in terms of fatigue and recovery, due to not seeing the sun for 48 h or more, unlike night shifts in the warmer months. Similarly, if early rounds of the convergent interviews raise the common issue of having regular sleep being conducive to recovery, the interviewers could generate a probe question to ask later rounds of interviewees to clarify when regular sleep may not be conducive to recovery. For example, that probe question could be, “Under what conditions would regular sleep not help recovery?”

Convergent interviewing focuses on key common issues. Therefore, any issues raised by only one interviewee were excluded from the process. This focus on key, common issues between the interviewees is a key difference between open interviewing until saturation relative to convergent interviewing. Later rounds of the convergent interviews asked the core question and the probe questions, generating a list of key issues and their relationships. Unlike standard interviews, which often need to continue until some sort of subjective ‘saturation’, convergent interviews have a set end-point, when there are two rounds with no new common issues—making them efficient and cost-effective, as well as powerful.

Demonstrating Qualitative Soundness of Convergent Interviewing

Demonstrating the soundness of qualitative techniques can be problematic, particularly due to the lack of universally agreed criteria by which to assess the research, where the positivistic criteria for assessing the soundness of research are inappropriate [37,38]. The soundness of the method used in this paper will be assessed relative to the criteria proposed by [37,39]. The alternative criteria are: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability. The meaning of each of the four inter-related criteria and their application to convergent interviewing are examined below.

Credibility is parallel to the positivist idea of internal validity, wherein an assessment is made of the match between realities, but rather than matching to an alleged objective reality, the assessed match is between the realities of the investigated and the investigator [38]. That is, the research has stronger credibility if it is conducted such that the subject matter was accurately identified and described [39]. A core technique used to enhance the credibility of the convergent interviews is the process of progressive subjectivity—the process of monitoring the inquirer’s own developing construction [38]. Throughout the interviewing process the researchers jointly developed and agreed upon probe questions, based on the common issues raised by the interviewees. Additional probe questions were included from the second round of interviews to the second-last round of interviews, to investigate common issues raised by the interviewees. None of the probe questions were developed in advance by the investigators. Assessments against the credibility criterion are further enhanced in that the results from the interviews, summarized in Figure 1, show how the majority of the detailed issues raised were not present in the literature background for the study, and thus were not a reflection of the investigators’ expectations or preconceptions.

The transferability of the research from one context to another entails a judgement regarding the relevance of the first study to the second setting. The transferability of qualitative research is achieved through analytical or theoretical generalization rather than the statistical generalization of quantitative research [40]. In part, transferability is achieved relative to the original theoretical framework that shows how data collection will be guided by concepts and models [30]. The literature basis of the study highlights the applicability of the method to the theoretical issues that are the focus of SWS. Further, the transferability within the target industry is strengthened in that the original focus was on paramedics across an entire state (with one of the largest paramedic organizations in Australia). That is, a notable portion of the experts on this specific topic available in the country had been involved. The sourcing of interviewees was focused on the interviewees’ high levels of expertise in the specific area of the initial question, where sources included experts from outside the focal organization. Presentations of the results to consultants and representatives of other paramedic organizations in Australia provided feedback that was strongly supportive of the convergent interviewing process.

Dependability is parallel to the positivist criterion of reliability. The key concern of dependability is the stability of data over time [38]. With qualitative research, instability usually occurs due to the investigators are bored, exhausted, or under extreme stress. One technique for assessing dependability is to document the logic of the process and method decisions. The process of convergent interviewing is detailed and tightly specified (e.g., see [32]), suggesting that repeating the process, especially with trained interviewers as was done in this study, would have obtained very similar results. Dependability is closely related to the criteria of confirmability and some of the points below could also be applied to the above criterion.

Confirmability is concerned with assuring that data, interpretations, and the outcomes of enquiries are rooted in a basis apart from the evaluator, and that are not simply figments of the researchers’ imaginations [38]. Confirmability is a measure of two things; first, that the researchers’ conclusions are reasonable, given the data collected; and second, how well the research could be confirmed by another. The second point is not to imply replicability, obtaining the same results by doing another case, but rather, the ability of another hypothetical researcher doing the same method in the same context and obtain the same results [40]. The overall effect across the rounds of convergent interviews is that the series of rounds of interviews convergences towards a conclusion. Each interview begins as open-ended as the first interviews, starting with the one initial question and keeping the interviewee talking using interpersonal skills such as non-committal noises and prompts. However the interviews in the later rounds tend to converge more rapidly on the common issues, not least because the interviewees are not as dissimilar as the interviewees in the earlier rounds.

The detailed and structured process of convergent interviewing enhances confirmability (and dependability). Sub-processes are also designed to enhance confirmability, particularly in terms of the probe questions only being generated from issues in common within a round, where common issues, especially issues in common between two experts with different perspectives, are likely to be confirmed by another following the same process. These requirements of the process provide a structure that strengthens the confirmability and dependability of convergent interviewing.

3. Results

The convergent interviews generated a model of the key, common issues impacting fatigue and recovery for paramedics in the host state. Figure 1 represents an interconnected system of sources and stakeholders across levels from industry to organizational issues, the paramedic, their personality, their family situation, and surface tensions in the system, as well as indicating the complexity of the issues in system.

The results of the convergent interviews demonstrate how the method generates results that reflect the key common issues of the particular situation. The employee involvement in the convergent interviews provides ownership of the results, which can enhance the degree of acceptance by employees of later proposed changes. For example, starting with the relatively innocuous-sounding issue of continuous demands noted at the top of the simplified representation of the results in Figure 1, these continuous demands have a direct effect on the fatigue levels of paramedics, with little down time before the next call-out. However, an interesting effect of continuous demands as a contributor towards fatigue is demonstrated by ‘ramping’, where paramedics have to remain with a patient at a hospital until the hospital is able to take the patient. The impact of the continuous demands on fatigue is a relatively hidden consequence of ramping and is just one of several key, common contributors to the fatigue of paramedics. The details for the aggregated issues in Figure 1 are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The details of the broader key issues summarized in Figure 1.

The elements inherent to the nature of the work occurred mostly at the level of the individual, but a few occurred at the team level, and several at the level of the organization, especially as a consequence of organizational processes. However, there were also a few factors that resulted from inter-organizational issues at the industry level (e.g., union-management impacts) and perhaps, most importantly, there were a lot of issues particularly impacting recovery from the non-work context. There were also some issues that explicitly had an impact from the non-work context to the work context (e.g., the lack of flexibility for non-work activities arising from the design of the roster system).

4. Discussion

This study applied convergent interviewing to diagnose the core, common issues causing paramedic fatigue and recovery that could be used to inform the development of a nested, systems-based approach to sustainable work systems. The results from the convergent interviews summarize the issues occurring and operating at different levels in paramedics’ lives. The results reflect relationships between and among levels, revealing cross-level interactions and informing design improvements or interventions. Some issues (e.g., age, the roster) had multiple, simultaneous differential relationships with fatigue and recovery, highlighting the complexity of the issues and the relationships within real-world systems.

The demands of paramedic work had several characteristics that were associated with fatigue. The absolute workload led to fatigue, the lack of downtime exacerbated the impact of the workload, and demands inherent to different types of callouts had varying impacts. The different demands may reflect the nature of paramedic work (per [17]), and the inductive, systems-oriented approach of convergent interviewing was able to capture those various qualities and the various cross-level sources of demand (e.g., at task level, by the organizational processes allocating trivial jobs, and the decisions of the receiving hospitals causing ramping). In the spirit of the Demand-Control-Support model, E-R model, and in a similar manner to other contexts, for example [20], social support from colleagues and the lack of structured social support at the unit level, did appear to be associated with facilitating more adaptive coping responses, or reducing rumination.

The rostering of shiftwork was found to have varying impacts depending on the system level and context. For example, in this particular organization there were specific shift patterns that were seen to have a more fatiguing effect. In a finding similar to [15], nightshifts in general were seen to have more of a negative impact and older paramedics on night shift tended to take longer to get back to their normal state. Similarly, there was a particular shift that was seen to be worse during winter (14 h night shifts) because it could mean the paramedic saw no daylight for 48 h or more at a time. The finding that the paramedic’s family stage at home impacted recovery is an extension of calls for shiftwork to be aligned with family life (e.g., [11]), where that aligning would vary depending on the family life stage. Unlike [11] though, this study found that scheduling was repeatedly and consistently given as a key source of fatigue problems and was problematic through several avenues.

The scheduling of rosters is an example of the complexity represented in the results. The complexity of the relationships with rostering found in this study suggests that, extending [11], fatigue management processes based on current bio-mathematical models calculated using hours worked, shift times, the number of hours between shifts and similar straightforward work-oriented variables may not be capturing much of the variance associated with causes of fatigue and drivers of recovery in this context. Future fatigue management models may need to incorporate more of the complexity of the relationships between issues across both the work and non-work spheres.

Further, within the complex set of relationships around rostering there was also a contradictory tension between paramedics wanting their days off to be protected in the industrial relations sense, yet by having the days off formally rostered, the overall structure of the roster was perceived to reduce the amount of flexibility paramedics had on their days off, thereby limiting what they could do in the down time to facilitate their recovery. (This contradictory tension is indicated visually with the double-lined, double-ended arrow in the mid-right hand side of Figure 1.) Similarly, while other sections of Figure 1 show how paramedics want more involvement in their family life, the financial demands of family make taking overtime shifts attractive, which together combine to both increase fatigue and simultaneously reduce recovery. Consequently, there are several contradictory or concerning combinations of issues associated with the rostering. One possible way forward in trying to resolve that focal point for these issues could be to develop processes and systems that allow more discretion by the paramedics over their shift scheduling. Similar suggestions have been proposed in nursing (e.g., see [11,41]), although in this context such systems may need to be explicitly matched to, or cater for, paramedics with families at different life stages.

Rest and vacation is associated with recovery, in a similar manner to [22], but the paramedics’ awareness of how long it’s been since their last vacation and the time until the next was also seen as a stressor, perhaps acting as a special form of rumination and consuming cognitive and emotional energy between vacations. Involvement in family life and the nature of the activities pursued during down time were just a few of the issues that impacted recovery and are similar to previous findings (e.g., [23]), although there was a specific recognition of the benefits of exercise. Again, the convergent interviewing method was able to delineate finely-specified issues that impact recovery, but a lot more of the issues were associated with fatigue.

Capturing the complexity of the inter-relationships between issues through the use of convergent interviews presents a level of diagnostic detail that can greatly enhance the later stages of any SWS or sociotechnical systems work. For example, the use of convergent interviews as part of the first stage of sociotechnical systems processes such as the IDEAS framework of [30], could help to pare-down and focus the efforts of later stages. The level of detail surfaced by the convergent interviewing at each level of the system and across levels of the system can substantially impact the likely success of later, tailored interventions regarding those issues. The synergies and complementarity between convergent interviewing and these diagnostic SWS analyses may be a reflection of their relatively inductive and participatory action-oriented organizational development heritage based on sociotechnical systems [31].

The convergent interviews also expanded the usual work-system focus of sociotechnical systems to more substantially include issues from outside work in order to reflect the broader system that is the paramedic’s life. The expansion in scope of the coverage to a broader system (covering work and non-work) may be a reflection of our aim to build towards sustainable models of work systems, where recovery mechanisms are included and the system can strive for a balance between work and recovery (as represented by the Effort-Recovery (E-R) model [10]). For example, on the fatigue side of Figure 1 the results include the core drivers of fatigue at the individual level and the organizational level in terms of work systems, but the inductive results show how analyses need to include many other issues and more clearly specify the varying nature of the relationships between the drivers of fatigue and/or recovery.

Possible interventions that could arise from downstream SWS work could range from fixing the OH&S information—making it more useful and engaging for staff, to having more sleep hygiene training, redesigning call allocation processes such that more of the trivial calls are allocated or processed differently. Interventions higher in the system(s) could include engaging the inter-organizational issues associated with fixing the ramping (which may need its own set of convergent interviews and a whole project). A more complex intervention process could be to improve the rostering, a set of processes that has a large number of stakeholders across many levels and consequently would probably need to be widely participatory. Direct solutions such as having a wider and more tailored variety of shifts, possibly with more staff discretion and/or shifts that are able to be tailored to family situations could be complicated and would include union-management relationships.

Thus the results in Figure 1 may lead to later stages in the SWS process having a phased approach that first looks to reduce the risk of many of these harmful outcomes through better education about sleep (often referred to as sleep hygiene). For example, an effective use of resources in these psychoeducation programs has a multi-faceted approach incorporating ‘expert-led’ group presentations, ‘train-the-trainer’ programs, and online psychoeducation tools (e.g., [42]). Whereas engaging the cross-level relationships and interactions through the design of improvements or interventions, though important and powerful (e.g., as found by [29]), may be addressed in one of the later phases.

Limitations

Subsequent research would be able to expand on the method used in this study. That is, there may be a need to assess the transferability of the process for generating the common issues applicable to SWS to a paramedic workforce in another state or country, or to other workforces. Further, convergent interviews are often used in mixed methods projects to generate the key common issues that are the focus of later survey scales.

5. Conclusions

This study has applied the sociotechnical systems modelling approach underpinning SWS to the broader system of paramedic life, covering both work and non-work issues, and highlighting the power and flexibility of convergent interviewing. An improved fatigue management approach could be informed by the findings of this study across multiple levels of intervention and offering increased flexibility in addressing risks and enabling activities tailored to issues at the source. The resulting systems-based influence diagram (summarized in Figure 1) enables the creation of phased interventions, where a small specific change may be made quickly, whereas elements of larger changes can be planned and begun, but may need greater resourcing or coordination or a longer time span to implement.

Convergent interviewing was applied to a paramedic context, taking a systems-based approach to analyze the work systems and by extending the standard sociotechnical systems approach to non-work systems. The inductive convergent interviewing process was able to encapsulate the complexity of the issues associated with fatigue and recovery in the paramedics’ lives. The convergent interviews enacted the initial stages of a sociotechnical systems approach [26], by summarizing the key social, technical and environmental issues at each level of the system and across levels of the system, along with an understanding of their inter-relationships, with the aim of being able to create and manage a sustainable work system where the human and social resources are regenerated [6].

This paper presents convergent interviews as a tool for the diagnostic stage of SWS analyses and interventions. Convergent interviews address the need for an organizational change planning tool that is pragmatic and applicable across levels within the system to inform moving that system to sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and L.T.; methodology, J.R. and L.T.; formal analysis, J.R. and L.T.; investigation, L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.; writing—review and editing, J.R. and L.T.; project administration, L.T.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Williamson, A.; Lombardi, D.A.; Folkard, S.; Stutts, J.; Courtney, T.K.; Connor, J.L. The link between fatigue and safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirallo, R.G.; Loomis, C.C.; Levine, R.; Woodson, B.T. The prevalence of sleep problems in emergency medical technicians. Sleep Breath. 2012, 16, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartenbaum, N.; Collop, N.; Rosen, I.M.; Phillips, B.; George, C.F.P.; Rowley, J.A.; Freedman, N.; Weaver, T.E.; Gurubhagavatula, I.; Strohl, K.; et al. Sleep apnea and commercial motor vehicle operators: Statement from the joint Task Force of the American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and the National Sleep Foundation. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 48 (Suppl. 9), S4–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Ploeg, E.; Kleber, R.J. Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: Predictors of health symptoms. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60 (Suppl. 1), i40–i46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasa, U.; Brulin, C.; Angquist, K.A. Barnekow-Bergkvist, M. Work-related psychosocial factors, worry about work conditions and health complaints among female and male ambulance personnel. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2005, 19, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docherty, P.; Forslin, J.; Shani, A.B.; Kira, M. Emerging work systems: From intensive to sustainable. In Creating Sustainable Work Systems: Developing Social Sustainability; Forslin, J., Docherty, P., Shani, A.B., Eds.; Routledgel: London, UK, 2002; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery, health and job performance: Effects of weekend experiences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Noblet, A.; McWilliams, J.; Rodwell, J.J. Abating the consequences of managerialism on the forgotten employees: The issues of support, control, coping and pay. Int. J. Public Adm. 2006, 29, 911–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological aspects of workload. In A Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology: Volume 2: Work Psychology, 2nd ed.; Drenth, P.J.D., Thierry, H., De Wolff, C.J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1998; pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Steege, L.M.; Dykstra, J.G. A macroergonomic perspective on fatigue and coping in the hospital nurse work system. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 54, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saksvik, I.B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Hetland, H.; Sandal, G.M.; Pallesen, S. Individual differences in shift work tolerance: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore-Ede, M.C.; Richardson, G.S. Medical implications of shift-work. Annu. Rev. Med. 1985, 36, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roennberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Juda, M.; Kantermann, T.; Allebrandt, K.; Gordijn, M.; Merrow, M. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, J.B.; Tom, J.; Zhai, Y.; Criswell, L.; Leo, E.; Ogoussan, K. Shiftwork impacts and adaptation among health care workers. Occup. Med. 2009, 59, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagie, A.; Krausz, M. What aspects of the job have most effect on nurses? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2003, 13, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, L.; McEachern, B.M.; MacPhee, R.S.; Fischer, S.L. Patient acuity as a determinant of paramedics’ frequency of being exposed to physically demanding work activities. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 56, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Carter, D. The ethics of ambulance ramping. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2017, 29, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblet, A.; Teo, S.T.T.; McWilliams, J.; Rodwell, J.J. Which work characteristics predict employee outcomes for the public sector employee? An examination of generic and occupation-specific Characteristics. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pow, J.; King, D.B.; Stephenson, E.; DeLongis, A. Does Social support buffer the effects of occupational stress on sleep quality among paramedics? A daily diary study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Zijlstra, F.R.H. Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M.; Eden, D. Effects of a respite from work on burnout: Vacation relief and fade-out. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Work, recovery activities, and individual well-being: A diary study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebbins, M.W.; Shani, A.B. Toward a sustainable work systems design and change methodology. In Creating Sustainable Work Systems: Developing Social Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Docherty, P., Kira, M., Shani, A.B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, B.M. Macroergonomics in large-scale organizational change. In Macroergonomics: Theory, Methods and Applications; Hendrick, H.W., Kleiner, B.M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; Chapter 13; pp. 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Karsh, B.T.; Waterson, P.; Holden, R.J. Crossing levels in systems ergonomics: A framework to support ‘mesoergonomic’ inquiry. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsh, B.; Holden, R.J.; Alper, S.J.; Or, K.L. A human factors engineering paradigm for patient safety e designing to support the performance of the health care professional. Qual. Saf. Healthc. 2006, 15 (Suppl. I), i59–i65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterson, P.E. A systems ergonomics analysis of the Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells infection outbreaks. Ergonomics 2010, 52, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.; Henning, R.; Warren, N.; Nobrega, S.; Dove-Steinkamp, M.; Tibirica, L.; Bizaro, A.; CPH-NEW Research Team. The Intervention Design and Analysis Scorecard: A planning tool for participatory design of integrated health and safety interventions in the workplace. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55 (Suppl. 12), S86–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, W.L.; Bell, C.H. Organization Development: Behavioral Science Interventions for Organization Improvement, 3rd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, R. Convergent Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Interchange: Brisbane, Australia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.; Collie, A. Worker’s Compensation Claims Among Nurses and Ambulance Officers, 2008/09-2013/14; ISCRR Report No. 118-0516-R03; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen, D.M.; Rodwell, J.J. Convergent Interviewing: A qualitative diagnostic technique for researchers. Manag. Res. News 2008, 31, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thynne, L.; Rodwell, J. A pragmatic approach to designing changes using convergent interviews: Occupational violence against paramedics as an illustration. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, R. Convergent Interviewing, version 20140907; Interchange: Brisbane, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation; Sage: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G.B. Designing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.L. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, J.; Fernando, J. Managing work across shifts: Not all shifts are equal. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, L.K.; O’Brien, C.S.; Rajaratnam, S.M.; Qadri, S.; Sullivan, J.P.; Wang, W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Implementing a sleep health education and sleep disorders screening program in fire departments. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).