Linking Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: The Drivers of Sustainability in High-Tech Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Direct Effect of Exploration and Exploitation on Organizational Performance

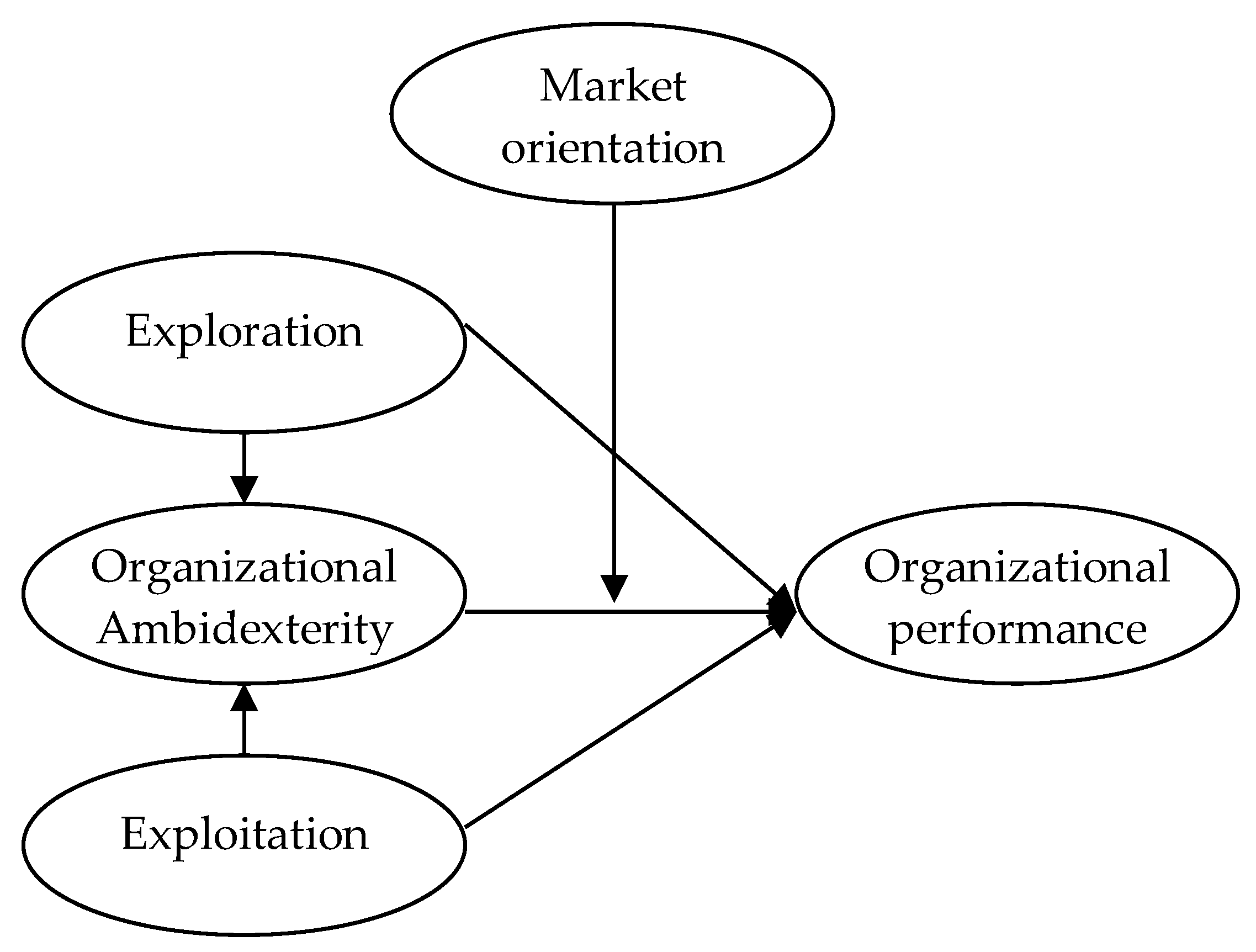

2.3. Effect of Combining Exploration and Exploitation on Organizational Performance

2.4. Moderating Effect of Market Orientation

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Assessment of Variables

4. Results

4.1. Measurement

4.2. Regression Results

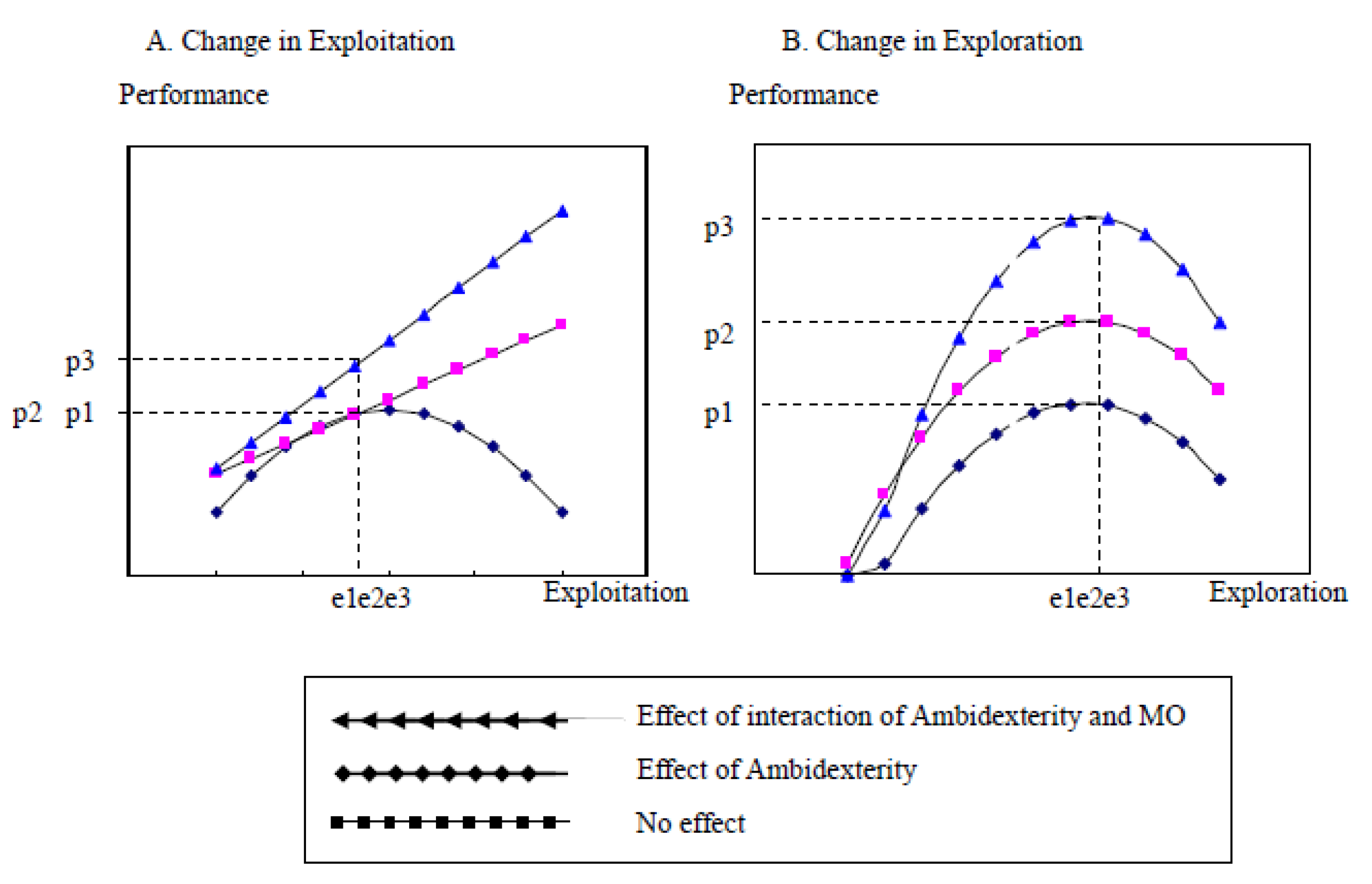

4.3. Post Hoc Examination of Findings

4.4. Analysis of Variance

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion and Implications

5.2. Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Botella-Carrubi, M.D.; González-Cruz, T.F. Context as a provider of key resources for succession: A case study of sustainable family firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.Y.P.; Lin, K.H. Impact of ambidexterity and environmental dynamism on dynamic capability development trade-offs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, S.; Shen, T. How can a firm innovate when embedded in a cluster? Evidence from the automobile industrial cluster in china. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Wang, P.K. Exploration and exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidextrous hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y. Entrepreneurial resources, dynamic capabilities and start-up performance of Taiwan's high-tech firms. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Hu, J.; Ouyang, T. Managing Innovation Paradox in the sustainable innovation ecosystem: A case study of ambidextrous capability in a focal firm. activities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.B. The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. In The Management of Organization Design: Strategies and Implementation; Kilmann, L.R., Pondy, D.S., Eds.; North Holland: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A. Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinit, P.; Tom, L.; Joakim, W. Exploration and exploitation and firm performance variability: A study of ambidexterity in entrepreneurial firms. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 1147–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance. Org. Sci. 2009, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.; March, J.G. The myopia of learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristal, M.M.; Roth, A.V.; Huang, X. The Effect of an ambidextrous supply chain strategy on combinative competitive capabilities and business performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking Organizational Ambidexterity: Dimensions, Contingencies, and Synergistic Effects. Org. Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S. The asymmetric role of market orientation on the ambidexterity firm performance relationship for prospectors and defenders. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkenshaw, J. The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Nieves, J.; Haller, S. Building dynamic capabilities through knowledge resources. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Reflections on “profiting from innovation”. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 1131–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y. Applicability of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views under environmental volatility. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, Z.J. Exploration versus exploitation in alliance portfolio: Performance implications of organizational, strategic, and environmental fit. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, P.; Shin, C.H. Becoming a sustainable organization: focusing on process, administrative innovation and human resource practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, S.; Ho, Y.P. Coworking and sustainable business model innovation in young firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Seo, Y.W. Strategies for sustainable business development: utilizing consulting and innovation activities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Org. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Org. Sci. 1991, 2, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; George, G.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Senior team attributes and organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of transformational leadership. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 982–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prange, C.; Verdier, S. Dynamic capabilities, internationalization processes and performance. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D. Organizing for Innovation. In Handbook of Organization Studies; Clegg, S.R., Hardy, C., Nord, W.R., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, P.S.; Goodman, J.M. Toward a workable framework. In New Perspectives on Organizational Effectiveness; Pennings, P.S., Goodman, J.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 146–184. [Google Scholar]

- Schreyogg, G.; Kliesch-Eberl, M. How dynamic can organizational capabilities be? Towards a dual-process model of capability dynamization. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Does competitive environment moderate the market orientation-performance relationship? J. Mark. 1994, 58, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.H.; Simek, Z.; Lin, Y.; Veiga, J.F. Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 646–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Celly, N. Strategic ambidexterity and performance in international new ventures. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2008, 25, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F.T.; Alexandre, M.T. Ambidexterity in technology sourcing: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Org. Sci. 2009, 20, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.F.; Hult, T. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: how do organizational antecedents. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2006, 57, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katila, R.; Ahuja, G. Something old, something new: A longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: managing paradoxes of innovation. Org. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Chen, R.R. Dynamic capability and IJV performance: The effect of exploitation and exploration capabilities. Asia Pacific. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 601–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, Y. An empirical investigation of knowledge management and innovative performance: The case of alliances. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebben, J.J.; Johnson, A.C. Efficiency, flexibility, or both? Evidence linking strategy to performance in small firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, A.M.; Posen, H. Is failure good? Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 617–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, R.A. Fading memories: A process theory of strategic business exit in dynamic environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 24–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, A.S.; Bassoff, P.; Moorman, C. Organizational improvisation and learning: A field study. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 304–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B.J. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and Organization: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.; Pflesser, C. A multiple-layer model of market-oriented organizational culture: measurement issues and performance outcomes. J.Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res. Org. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Management team learning orientation and business unit performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Tushman, M.L. Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Org. Sci. 2005, 16, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration | Introduce a new generation of products | He and Wong [4], Lubatkin et al. [32], Menguc and Auh [16], and Cao et al. [15] |

| Extend the product range | ||

| Open up new markets | ||

| Enter into new technology fields | ||

| Innovations in marketing techniques | ||

| Exploitation | Improve existing product quality | |

| Improve production flexibility | ||

| Reduce production cost | ||

| Improve yield or reduce material consumption | ||

| Customer orientation | Our business objectives are driven by customer satisfaction | Menguc and Auh [16], Narver and Slater [32], and Kohli and Jaworski [48] |

| We closely monitor and assess our level of commitment to serving customers’ needs | ||

| Our competitive advantage is based on understanding customers’ needs | ||

| Business strategies are driven by the goal of increasing customer value | ||

| We frequently measure customer satisfaction | ||

| We pay close attention to after-sale service | ||

| Competitor orientation | In our organization, our salespeople share information about competitors | |

| We respond rapidly to competitive actions | ||

| We regularly discuss competitors’ strengths and weaknesses | ||

| Customers are targeted when we have an opportunity for a competitive advantage | ||

| Inter-functional coordination | We share resources with other business units | |

| Our managers understand how employees can contribute to customer value | ||

| Our top managers from each business function regularly visit customers | ||

| Business strategies are driven by the goal of increasing the customer value | ||

| Business functions are integrated to serve the target market’s needs | ||

| Organizational effectiveness | Product quality | Narver and Slater [32,33], Jaworski and Kohl [34], Lubatkin et al. [35], and Han and Celly [36] |

| New product success rate | ||

| Customer retention rate | ||

| Growth/share | Sales | |

| Growth rate | ||

| Targeted market share | ||

| Profitability | Return on Equity (ROE) | |

| Gross margin | ||

| Return on Investment (ROI) |

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exploration | (0.831) | ||||||

| 2. Exploitation | 0.449 *** | (0.728) | |||||

| 3. Market orientation | 0.443 *** | 0.283 *** | (0.741) | ||||

| 4. Organizational performance | 0.281 *** | 0.569 *** | 0.376 *** | (0.755) | |||

| 5. Ambidexterity | 0.895 *** | 0.776 *** | 0.401 *** | 0.482 *** | - | ||

| 6. Firm size (square root) | −0.129 | −0.038 | 0.027 | 0.027 | −0.117 | - | |

| 7. Firm age (square root) | 0.130 | 0.063 | 0.046 | −0.064 | 0.104 | 0.458 *** | - |

| Means | 4.93 | 4.93 | 5.15 | 4.74 | 0.68 | 2.57 | 3.32 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.15 | 1.11 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 1.35 | 1.45 | 1.11 |

| α | 0.933 | 0.857 | 0.803 | 0.908 | - | - | - |

| AVE | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.57 | - | - | - |

| CR | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.92 | - | - | - |

| Variables | Organizational Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Control variables | ||||

| Firm size | 0.135 + | 0.128 + | 0.139 + | 0.094 |

| Firm age | −0.170 * | −0.179 * | −0.170 * | −0.158 * |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Exploration | 0.072 | 1.059 * | 0.236 | 0.120 |

| Exploitation | 0.552 *** | −0.482 | −0.142 | −0.598 |

| Explorative2 | −0.984+ | −0.999 * | −1.615 ** | |

| Exploitative2 | −0.836+ | 0.128 | 0.184 | |

| MO | 0.336 *** | |||

| Interaction | ||||

| Ambidexterity | 1.207 * | 1.915 ** | ||

| Ambidexterity * MO | 0.181 * | |||

| F-value | 19.695 *** | 14.193 *** | 13.115 *** | 15.362 *** |

| R2 | 0.349 | 0.370 | 0.389 | 0.493 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.331 | 0.344 | 0.360 | 0.461 |

| Max VIF | 1.832 | 1.984 | 2.132 | 2.323 |

| Firms | n | Exploration | Exploitation | Firm Size | Firm Age | Firm Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 36 | 3.73 | 3.51 | 2.50 | 3.22 | 4.26 |

| Group 2 | 22 | 3.78 | 4.95 | 2.82 | 3.55 | 4.50 |

| Group 3 | 10 | 5.80 | 4.10 | 2.20 | 2.80 | 4.38 |

| Group 4 | 84 | 5.63 | 5.63 | 2.57 | 3.36 | 5.15 |

| F | 152 | 91.837 *** | 94.208 *** | 0.455 | 1.169 | 13.081 *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, M.Y.-P.; Lin, K.-H.; Peng, D.L.; Chen, P. Linking Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: The Drivers of Sustainability in High-Tech Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143931

Peng MY-P, Lin K-H, Peng DL, Chen P. Linking Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: The Drivers of Sustainability in High-Tech Firms. Sustainability. 2019; 11(14):3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143931

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Michael Yao-Ping, Ku-Ho Lin, Dennis Liute Peng, and Peihua Chen. 2019. "Linking Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: The Drivers of Sustainability in High-Tech Firms" Sustainability 11, no. 14: 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143931

APA StylePeng, M. Y.-P., Lin, K.-H., Peng, D. L., & Chen, P. (2019). Linking Organizational Ambidexterity and Performance: The Drivers of Sustainability in High-Tech Firms. Sustainability, 11(14), 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143931