Implementing Innovation on Environmental Sustainability at Universities Around the World

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art: Innovation and Sustainability at Universities Today

3. Methodology: A Survey of Innovation and Sustainability at Universities

3.1. Survey Design

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sustainability

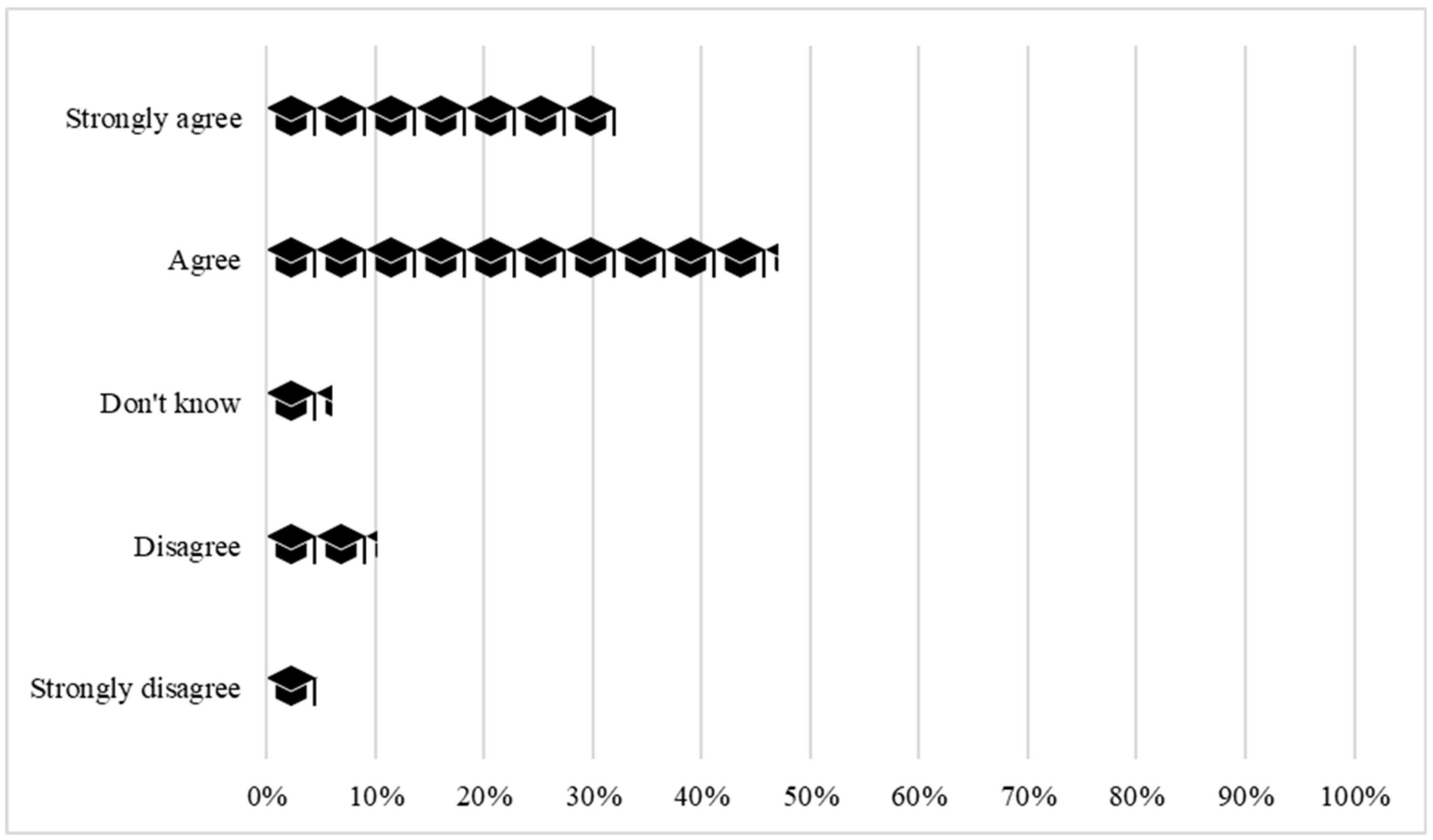

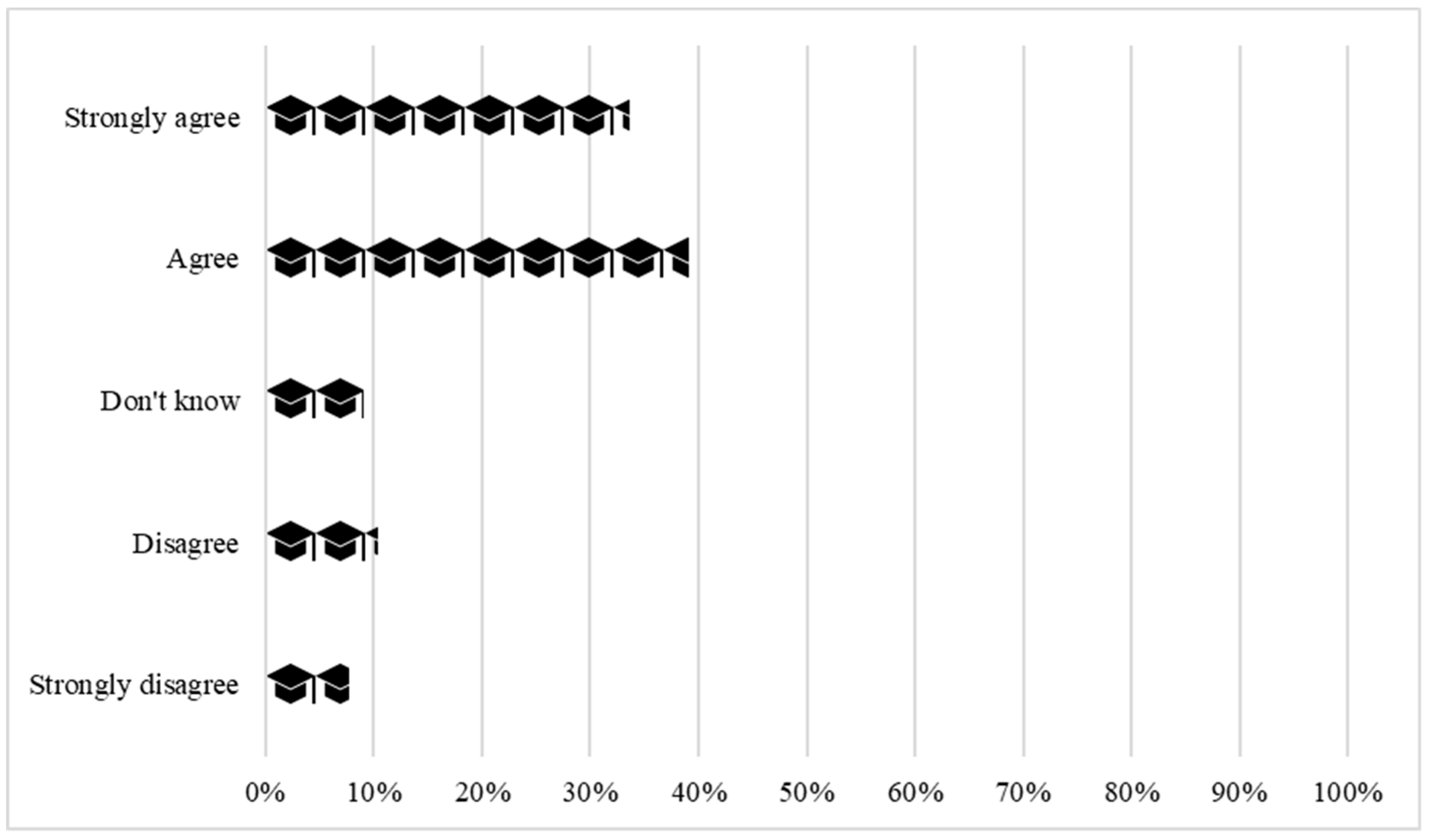

4.1.1. University Involvement

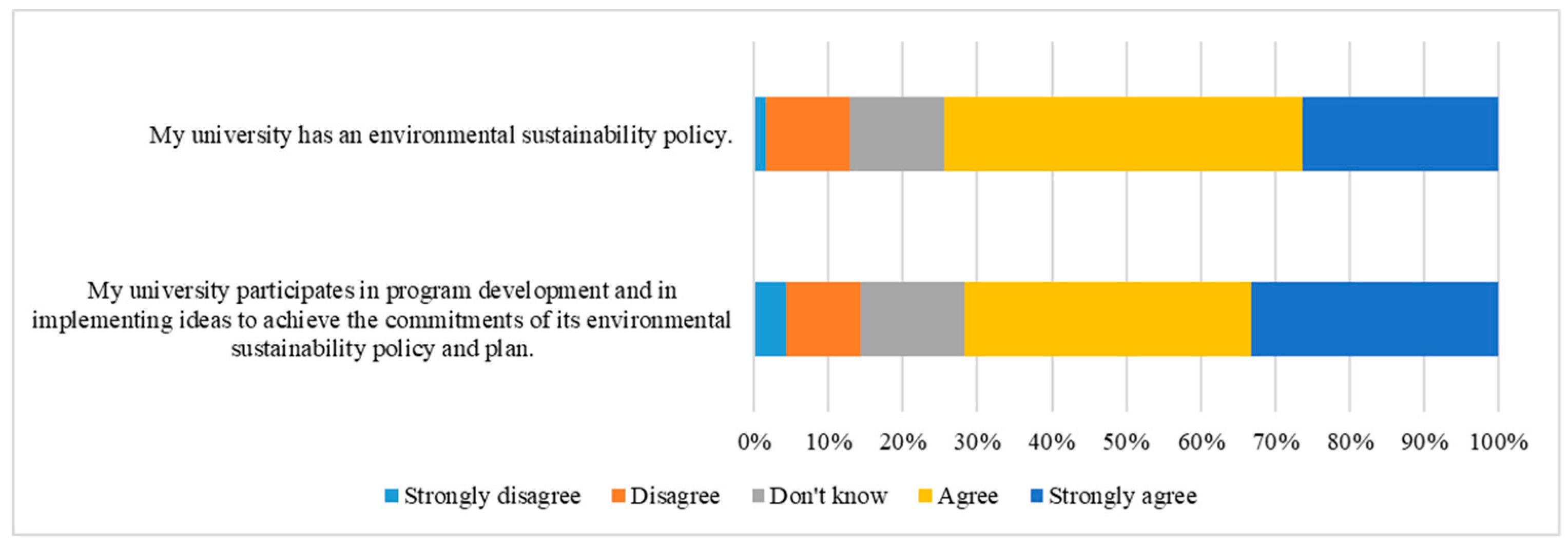

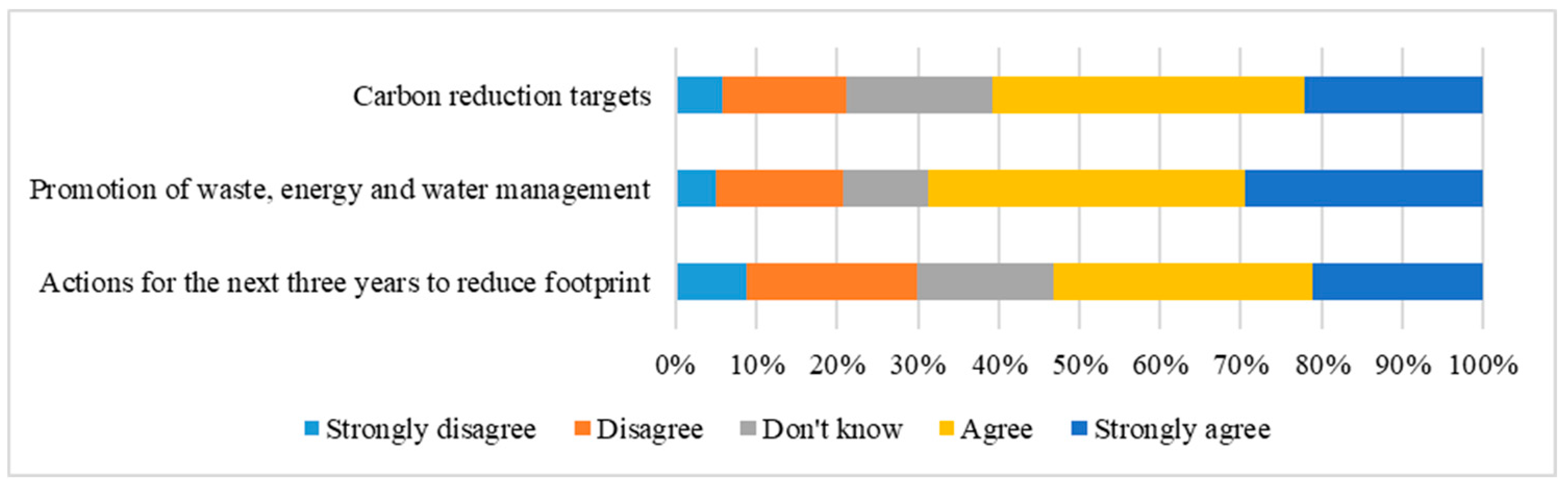

4.1.2. Operations

4.1.3. Student Involvement

4.2. Innovation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD/Eurostat. Oslo Manual, Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hautamäki, A.; Oksanen, K. Sustainable innovation: Solving wicked problems through innovation. In Open Innovation: A Multifaceted Perspective; Mention, A.-L., Torkkeli, M., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2016; pp. 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre, B.S. A hard nut to crack! Implementing supply chain sustainability in an emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, J.; Holliday, C. Innovation, Technology, Sustainability and Society; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: http://www.bvsde.paho.org/bvsacd/cd30/society.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Boons, F.; Montalvo, C.; Quist, J.; Wagner, M. Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebode, D.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J. Managing innovation for sustainability. RD Manag. 2012, 42, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/ecosoc/en/sustainable-development (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- European Union. Report on the EU and the Global Development Framework after 2015. European Union. Committee on Development. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+REPORT+A8-2014-0037+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Lubchenco, J.; Karl, T.R. Predicting and managing extreme weather events. Phys. Today 2012, 65, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S.M.; Keng, K.C.; Cane, M.A. Civil conflicts are associated with the global climate. Nature 2011, 476, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, B. An integral framework for permaculture. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 3, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, B.; Salverda, W.; Checchi, D.; Marx, I.; McKnight, A.; Tóth, I.G.; Van de Werfhorst, H.G. Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; p. 784. [Google Scholar]

- UN Environment. Global Environment Outlook GEO-6: Healthy Planet, Healthy People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-6 (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- United Nations. Conference on Environment and Development: Agenda 21, 1992. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Halifax Declaration. Creating a Common Future, 1991. Available online: www.iau-aiu.net/content/rtf/sd_dhalifax.rtf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- ULSF-University Leaders for a Sustainable Future. The Talloires Declaration 10 Point Action Plan, 2015. Available online: http://ulsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/TD.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- COPERNICUS-CAMPUS. Education for Sustainable Development, 2012. Available online: http://webarchive.unesco.org/20161026153813/http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=34756&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Holm, T.; Sammalisto, K.; Grindsted, T.S.; Vuorisalo, T. Process framework for identifying sustainability aspects in university curricula and integrating education for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, G. Policy, politics and polity in higher education for sustainable development. In Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Barth, M., Michelsen, G., Rieckmann, M., Thomas, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dlouhá, J.; Glavič, P.; Barton, A. Higher education in Central European countries-Critical factors for sustainability transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, L.; Nuttman, S. Engaging higher education institutions in the challenge of sustainability: Sustainable transport as a catalyst for action. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Christ, G.; Sterling, S.; Van Dam-Mieras, R.; Adomßent, M.; Fischer, D.; Rieckmann, M. The role of campus, curriculum, and community in higher education for sustainable development—A conference report. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R. Environmental Literacy in Science and Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; p. 656. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S.; Maxley, L.; Luna, H. The Sustainable University: Progress and Prospects; Abingdon: Routledge, UK, 2013; p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, J.; Cotton, D.; Warwick, P. The university as site of socialisation for sustainability education. In Teaching Education for Sustainable Development at University Level; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D.P.; Walker, C.; Williams, K.; Rayner, J.; Farrell, C.; Butt, A.; Rostan-Herbert, D. Engaging students with environmental sustainability at a research intensive university: Examples of small successes. In Teaching Education for Sustainable Development at University Level; Leal Filho, W., Pace, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Lambrechts, W.; Lukman, R.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I. Challenges for implementation of education for sustainable development in higher education institutions. In Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Barth, M., Michelsen, G., Rieckmann, M., Thomas, I., Eds.; London: Routledge, UK, 2016; pp. 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, C.; Creech, H. Shaping the Future We Want: UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development; Final Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230171 (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Ávila, L.V.; Leal Filho, W.; Brandli, L.; Macgregor, C.J.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Özuyar, P.G.; Moreira, R.M. Barriers to innovation and sustainability at universities around the World. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.; Tilbury, D.; Corcoran, P.B.; Abe, O.; Nomura, K. Sustainability in Higher education in the Asia-Pacific: Developments, challenges and prospects. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrán Jorge, M.; Herrera Madueño, J.; Calzado Cejas, M.Y.; Andrades Peña, F.J. An approach to the implementation of sustainability practices in Spanish universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.; Tassone, V.C.; Hampson, G.P.; Reams, J. Learning for walking the change: Eco-social innovation through sustainability-oriented higher education. In Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Barth, M., Michelsen, G., Rieckmann, M., Thomas, I., Eds.; London: Routledge, UK, 2016; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, D.D.; Bell, K.P.; Lindenfeld, L.A.; Jain, S.; Johnson, T.R.; Ranco, D.; McGill, B. Strengthening the role of universities in addressing sustainability challenges: The Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions as an institutional experiment. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, L.A.; Bossert, M. The University Campus as Living Lab for Sustainability—A Practitioners Guide and Handbook; TU Delft: Delft, The Netherlands; Fachhochschule fur Technik Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-940670-68-7. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, K.Y.G.; Van Bueren, E.M. Urban Living Labs: A Living Lab Way of Working AMS Research Report; AMS Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Available online: https://www.ams-amsterdam.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/AMS-Living-Lab-Way-of-Work-print.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Keyson, D.V.; Guerra-Santin, O.; Lockton, D. Living Labs: Design and Assessment of Sustainable Living; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, L.A.; Bossert, M.; Newman, J.; Ferraz, F.; Robinson, Z.P.; Agarwala, Y.; Wolff, P., III; Jiranek, P.; Hellinga, C. Towards a learning system for University Campuses as Living Labs for sustainability. In Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A.L., Pretorius, R., Brandli, L., Manolas, E., Alves, M.F.P., Azeiteiro, U., Rogers, J., Shiel, C., Paço, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, L.; Graamans, L.; Gioutsos, D.; van Wijk, A.; Geraedts, J.; Hellinga, C. ShowHow: A Flexible, Structured Approach to Commit University Stakeholders to Sustainable Development. In Handbook of Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Azeiteiro, U., Alves, F., Molthan-Hill, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. Does better for the environment mean less tasty? Offering more climate-friendly meals is good for the environment and customer Satisfaction. Appetite 2015, 95, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Pretorius, R.; Brandli, L.; Manolas, E.; Alves, F.; Azeiteiro, U.; Rogers, J.; Shiel, C.; Do Paco, A. Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development-Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, A.V. Experiential learning in “innovation for sustainability” An evaluation of teaching and learning activities (TLAs) in an international masters course. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1204–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, P.; Sciulli, N. Sustainability Reporting by Australian Universities. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2016, 76, 87–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheim, A. How green is green? Developing a process for determining sustainability when planning campuses and academic buildings. Plan. High. Educ. 2003, 31, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, A.D. Integrating sustainability in the learning community. Facil. Manag. 2005, 21, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Abubakar, I. An integrated approach to achieving campus sustainability: Assessment of the current campus environmental management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, D.E. How do Universities Make Progress? Stakeholder-Related Mechanisms Affecting Adoption of Sustainability in University Curricula. J. Bus. Eth. 2013, 118, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, L.A. De Campus als Living Lab voor de Circulaire Economie. In Circulariteit, Op Weg Naar 2050; Luscuere, P., Ed.; TU Delft Open: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018; p. 261. ISBN 978-94-6366-054-9. [Google Scholar]

- Green Gown Awards. Available online: http://www.greengownawards.org.uk (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. L’analyse de Contenu; Presses Universitaires de France Le Psychologue: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, S.; Ijab, M.T.; Sulaiman, H.; Md. Anwar, R.; Norman, A.A. Social media for environmental sustainability awareness in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, A.; Steiner, G. Integrating research and teaching on innovation for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2006, 7, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomßent, M.; Grahl, A.; Spira, F. Putting sustainable campuses into force: Empowering students, staff and academics by the self-efficacy Green Office Model. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Brandli, L.L.; Becker, D.; Skanavis, C.; Kounani, A.; Sardi, C.; Papaioannidou, D.; Paço, A.; Azeiteiro, U.; Sousa, L.; et al. Sustainable development policies as indicators and pre-conditions for sustainability efforts at universities: Fact or fiction? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester University. MU’s Sustainability Policy. Available online: https://www.manchester.edu/about-manchester/university-priorities/green-campus-initiative/sustainability (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Harvard University. Harvard Sustainability Plan. Available online: https://green.harvard.edu/campaign/our-plan (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Vargas, V.R.; Lawthom, R.; Prowse, A.; Randles, S.; Tzoulas, K. Sustainable development stakeholder networks for organisational change in higher education institutions: A case study from the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Portela, N.; Benayas, J.; Pertierra, L.R.; Lozano, R. Towards the integration of sustainability in Higher Eeducation Institutions: A review of drivers of and barriers to organisational change and their comparison against those found of companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | Topic | Assessed Issues | Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| General | Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondent and university | Country, region, role | -- |

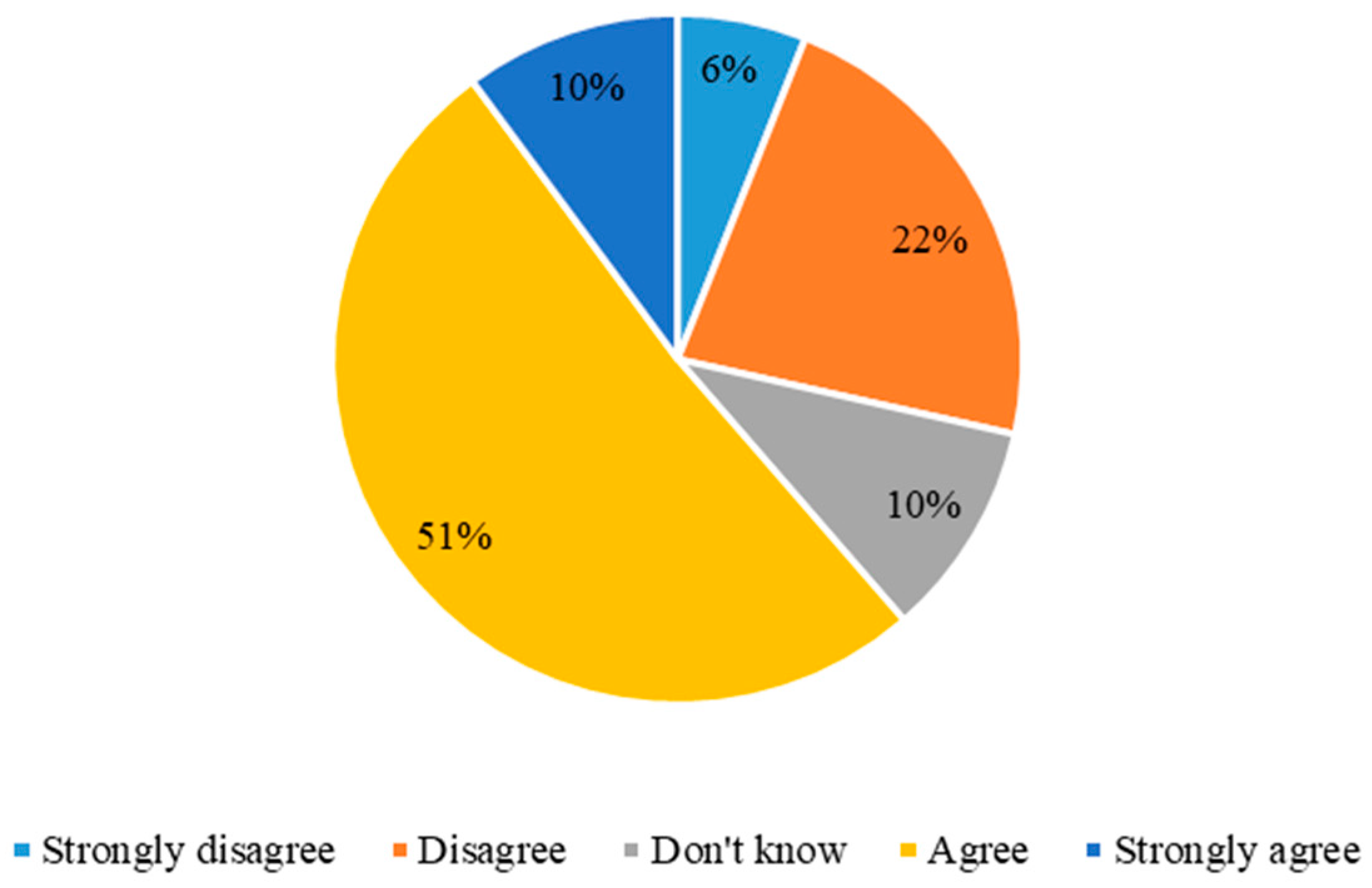

| Sustainability | University’s participation in awareness-raising activities | My university participates in awareness-raising activities and assists with distributing information and advice. | Strongly disagree, Disagree, Do not know, Agree, Strongly agree |

| Environmental sustainability team and environmental sustainability policy | My university has an environmental sustainability team who raise awareness of environmental sustainability across the organisation. My university has an environmental sustainability policy. | ||

| Importance given to programme development to achieve the commitments of its environmental sustainability policy and plan | My university participates in program development and in implementing ideas to achieve the commitments of its environmental sustainability policy and plan. | ||

| Actions planned to demonstrate the commitment to reduce the university’s environmental footprint and to improve the environmental performance | My university has planned its actions for the next three years to demonstrate its commitment to reducing the university’s environmental footprint and seeking to continually improve its environmental performance. | ||

| Promotion of waste, energy, and water management and the benefits of active travel | My university promotes improved waste, energy, and water management and the benefits of active travel. | ||

| Carbon reduction targets at the university | My university contributes in its operation to achieve the carbon reduction targets set by the government. | ||

| Education of students about the impact of climate change | My university educates its students about the impact of climate change on the discipline chosen by the student. | ||

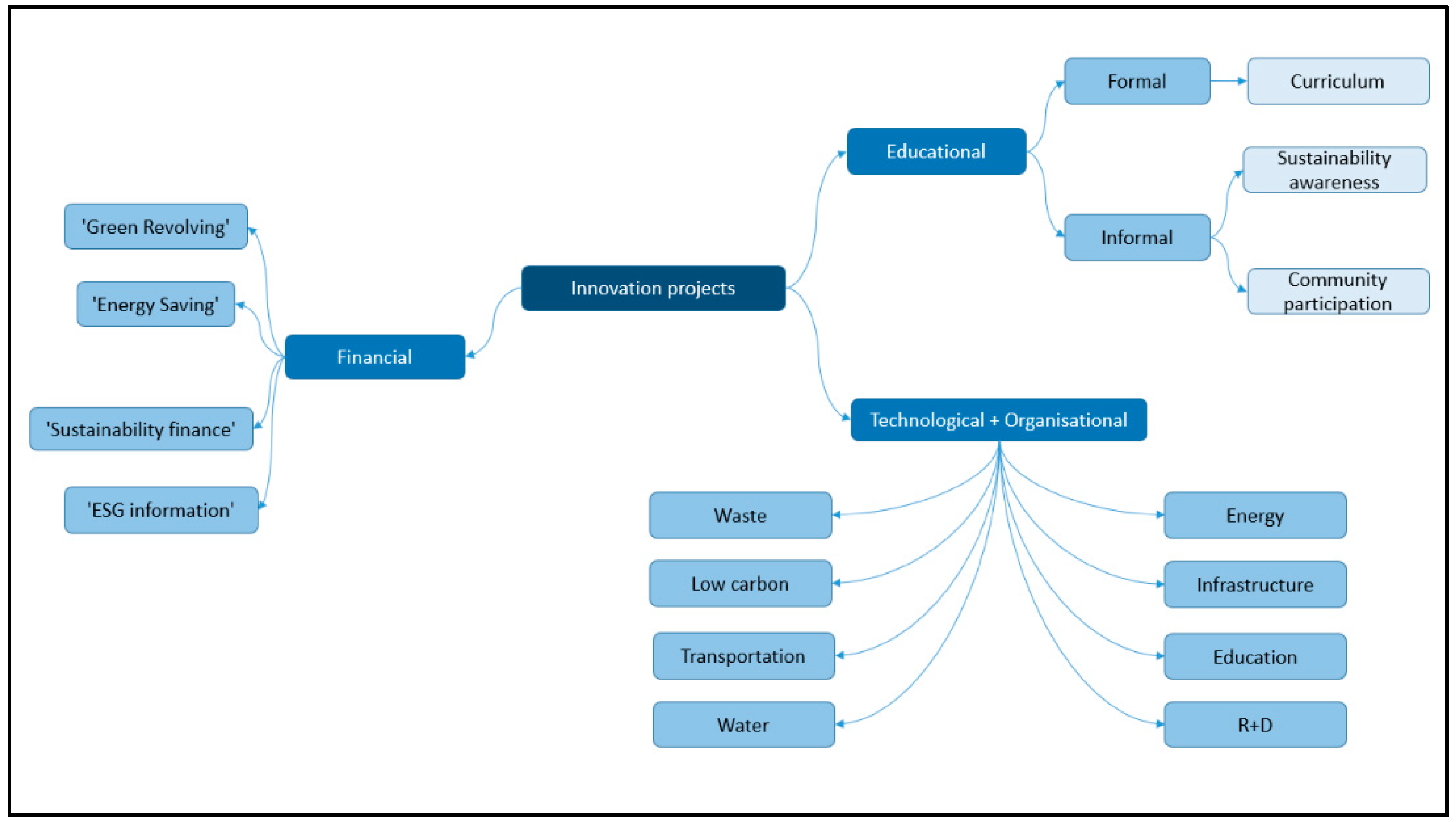

| Innovation | Scope of last/current project of innovation and the objectives involved in the project | What scale is the scope of your current or last project/programme? What objectives were involved in this project? | university-wide, faculty, department, support services, other new buildings, renovations, mobility, services, other |

| Innovation implemented in the program and how the innovation was managed | What kind of innovation was implemented? How did you manage/organise innovation? | technological, organisational, educational, financial, other living lab tools, technology readiness levels (TRLs), research and development (R&D) management, adoption theories, other | |

| Standards used to reach a better performance | Which standards were used to come to new/better performance? | BREEAM, WELL, ISO14000, in-house standard, other | |

| Open questions | Description of the most successful project/program on innovation and sustainability, their nature, innovative aspects, benefits, challenges/problems and publication of results. | -- |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leal Filho, W.; Emblen-Perry, K.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Mifsud, M.; Verhoef, L.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Bacelar-Nicolau, P.; de Sousa, L.O.; Castro, P.; Beynaghi, A.; et al. Implementing Innovation on Environmental Sustainability at Universities Around the World. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143807

Leal Filho W, Emblen-Perry K, Molthan-Hill P, Mifsud M, Verhoef L, Azeiteiro UM, Bacelar-Nicolau P, de Sousa LO, Castro P, Beynaghi A, et al. Implementing Innovation on Environmental Sustainability at Universities Around the World. Sustainability. 2019; 11(14):3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143807

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeal Filho, Walter, Kay Emblen-Perry, Petra Molthan-Hill, Mark Mifsud, Leendert Verhoef, Ulisses Miranda Azeiteiro, Paula Bacelar-Nicolau, Luiza Olim de Sousa, Paula Castro, Ali Beynaghi, and et al. 2019. "Implementing Innovation on Environmental Sustainability at Universities Around the World" Sustainability 11, no. 14: 3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143807

APA StyleLeal Filho, W., Emblen-Perry, K., Molthan-Hill, P., Mifsud, M., Verhoef, L., Azeiteiro, U. M., Bacelar-Nicolau, P., de Sousa, L. O., Castro, P., Beynaghi, A., Boddy, J., Lange Salvia, A., Frankenberger, F., & Price, E. (2019). Implementing Innovation on Environmental Sustainability at Universities Around the World. Sustainability, 11(14), 3807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143807