1. Introduction

Turkish Ministry of National Education has imposed a new model in school management through project schools (PS). According to this new model, length of service for PS managers and teachers is limited to 4 + 4 years, i.e., 8 years in total. In addition, PS principals have been given the authority to build their own teaching staff. This allows school managers to select their deputy directors and teachers and gives them the right to review their performance both internally and externally. These changes are brand new and innovative approaches in the Turkish National Education System.

Achieving the main goals of project schools, which involves building more efficient and successful schools with the new management approach, is believed to depend upon the balance between the objectives of organization and the individual purposes of the staff. This can be shortened to maximizing the organizational commitment (OC) of the staff [

1]. As the OC of the staff increases, it gets easier for them to adopt the organization’s objectives and identify themselves with the organization, their devotion deepens [

2], and they can effectively fulfill their roles and sustain their voluntary involvement in the organization [

3].

1.1. Organizational Sustainability

Sustainability is described as meeting modern-day needs without endangering the future generation’s ability to do the same [

4]. Global sustainability has been defined by the World Commission on Environment and Development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” [

5].

As the sustainability concept includes economic, societal, and environmental targets, it can be defined with these three different dimensions which are all interdependent [

4,

6]: economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, and social sustainability [

7]. Economic sustainability comprises financial health, economic performance, potential financial benefits, and trading opportunities of the organization. Social sustainability covers the areas of internal human resources, external population, stakeholder participation, and macro social performance [

8]. In terms of stakeholder theory, this implies that organizations should not only fulfill the wants and expectations of their stakeholders, but also avoid actions that reduce the ability of interested parties, including future generations, to meet their needs [

9].

Organizations are global partners for sustainable development and located at the core of organizational sustainability movement [

10]. Organizational sustainability is the management of opportunities and risks generated by economic, ecological, and societal development [

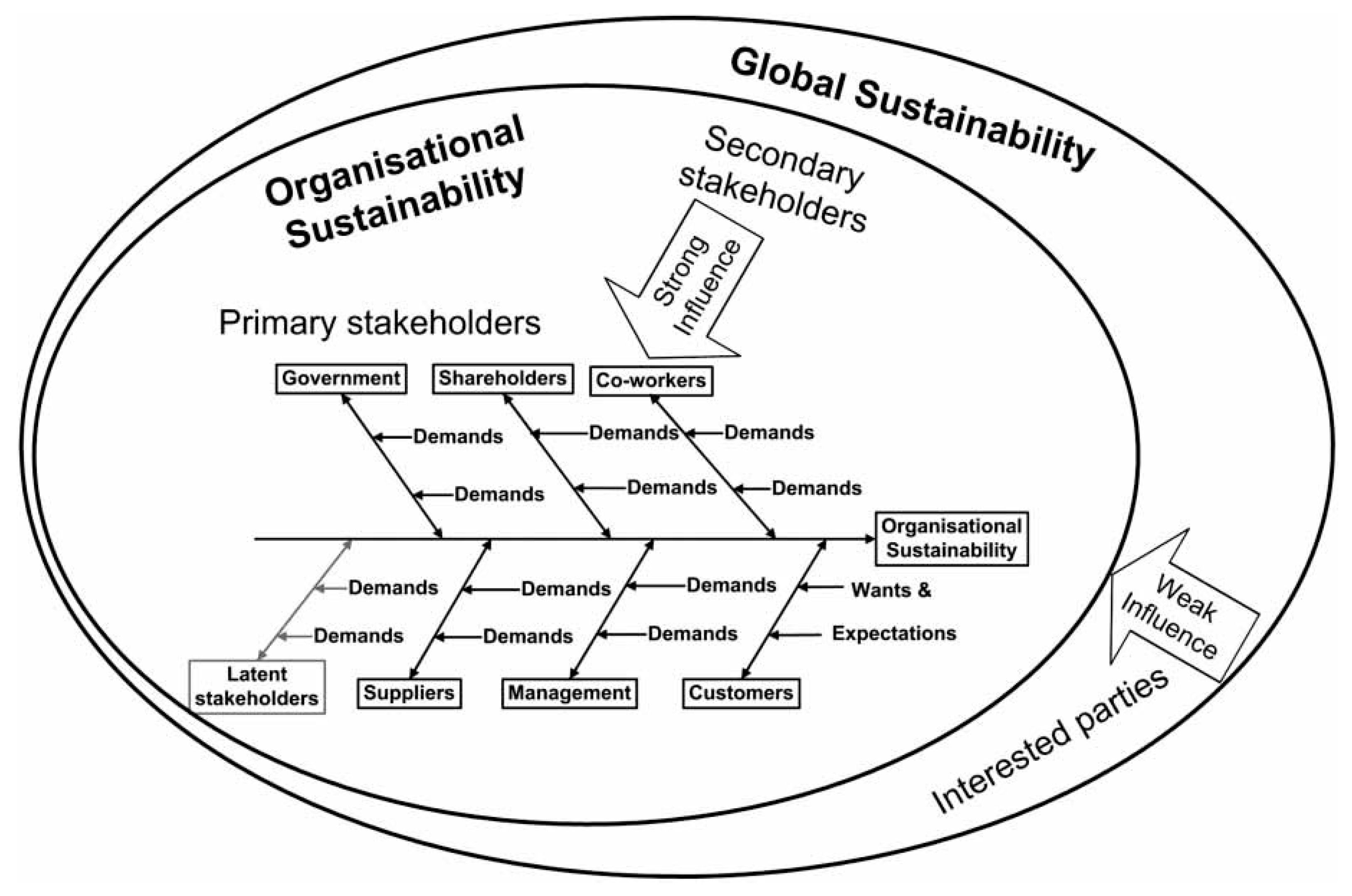

11]. The relation between sustainable development and organizational sustainability is shown in

Figure 1.

Organizations realize that economic, societal, and environmental sustainability contribute to the continuity of organizational life in connection with each other and try to meet these requirements [

12,

13,

14]. All organizations and corporations aim at surviving and they all are established for that purpose. It is not possible for an organization who cannot survive to meet current and future stakeholders’ needs in line with the organization’s organizational sustainability targets [

15]. Apart from the standard meaning to be attributed to the concept of sustainability, one of the conditions required for sustainable development is to ensure that the internal resources (human, financial, and infrastructural) of the organization are used in a profitable way and that they can be continuously renewed [

16].

Organizational sustainability can be defined as addressing the economic, societal, and environmental dimensions of sustainability in a balanced manner with organizational management principles [

17]. Organizational sustainability is based on the assumption that a qualified workforce with a high level of motivation and with certain abilities is rare and that these resources are sustained in the future. Therefore, organizations in general try to balance through the reproduction of their workforce [

18]. If environmental sustainability as an aspect of organizational sustainability also correlates with improved OC, then it may also serve as a strategy for reducing turnover in organizations, given that other necessary conditions are met, such as fair wages and safe working conditions [

19].

1.2. The Concept of Organizational Commitment

OC refers to the desire of employees to go to their workplace regularly, being at that workplace regularly, and integrating with that organization’s objectives [

4,

20,

21,

22]. High levels of OC may result in adopting the values and goals of the organization, exhibiting enthusiasm and utmost efforts in line with the organizational interests, and willingness to continue membership in the organization [

23,

24]. Researchers increasingly encourage OC and teamwork because teamwork is more important for group-oriented behavior and team effectiveness [

25,

26,

27]. Numerous studies have revealed the relationships between both OC and its outcomes and OC and its causes [

4,

28,

29]. OC has a positive effect on increasing employee performance, decreasing unwanted behaviors such as absenteeism and frequent tardiness [

30]; handling difficult work-related situations under pressure [

31]; and maintaining the assets, targets, and activities of organizations [

32,

33].

Among the factors affecting OC, the intra-organizational factors play an important role in teachers’ OC. Scholars note that while personal factors such as age, marital status, and gender tend to be effective in groups of employees with low-status jobs [

34], intra-organizational factors such as management, leadership, organization type, organization culture, organizational justice, and teamwork are more effective in groups of employees with high-status jobs. For the latter group, variables such as participating in decision-making processes, role ambiguity, and autonomy come to the fore as much more important factors in terms of commitment [

28]. School principals paying more attention to cooperation and sharing and fair treatment to teachers increases teachers’ sense of justice and equality [

3] and are of great importance in terms of maintaining OC [

35,

36].

1.3. The Relationship between Organizational Sustainability and Organizational Commitment

According to the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, organizations that want to ensure their sustainability should have a high level of mastery to cope with global and industrial challenges in different fields [

37]. As it can be seen in

Figure 1, there are many shareholders that affect organizational sustainability. One of them is the human factor. This means directing human resources through the best organizational learning practices is important in order to maintain labor skills and employee satisfaction [

37]. Organizational sustainability includes improved employee morale, more efficient business processes, a stronger public image, and increased employee loyalty. By influencing how employees work, the effective utilization of human resources is critical to the success of sustainability endeavors in any organization. Studies done in the field have demonstrated that high-performance human resource practices are extremely valuable in enhancing competitive advantage [

38].

A country’s education has always served as one of the most important and sensitive barometers of its prosperity, integrity, development, and, above all, sustainability. In this context, sustainability refers not only to the ecology and the environment, but also to the ability of an organization or a system to be maintained at a certain level or rate of performance that can continue or be continued for an indefinite period. Sustainability, therefore, suggests an activity or, more properly, a set of interrelated activities that is viable for an extended period of time [

16]. It is possible to say that the sustainable management system stands at the core of various sustainability-driven business applications targeting transformation. The most important factor in achieving targets is human resources [

39,

40]. The most important problem organizations face in terms of maintaining sustainability is ineffective human power [

41]. Managers must use human capital elements effectively and productively along with the material resources in covering the needs of present and future human demands and expectations in accordance with sustainability principles [

42]. Leaders need to reconcile with others, assure their followers, and pay attention to efficient teamwork [

42,

43]. In addition, in order to ensure the sustainability of the quality in the organizations, it is necessary to provide training to the employees at the levels required by their duties, powers, and responsibilities and also make this training sustainable [

44].

Having teamwork, maintaining employee participation, keeping intra-organizational communication channels open, and evaluating employee performance based on objective criteria, thus getting positive worker output, clears the way for sustainability [

45,

46,

47]. Measuring employee performance periodically helps maintain the sustainability of employee development [

48]. Numerous works in the last century focus on human capital, namely, the skills of employees with respect to the success and development of organizations have posited that the success of an organization depends on the creativity, innovativeness, and sense of responsibility of its employees [

49]. Many organizations are highly concerned about employee behavior for a number of reasons. Poor employee behavior decreases organizational performance, increases financial losses, damages reputations, increases safety concerns, and causes loss of customers [

50]. In addition, there is a positive relation between sustainable management and organizational culture [

51,

52]. In order to achieve sustainable management, employees should benefit from the organizational culture, as satisfaction is among the key internal variables of sustainability [

53].

1.4. Characteristics of Project Schools and Their Relationship with Organizational Sustainability

A PS is defined as a school within the framework of cooperation agreements with domestic/foreign institutions/organizations or countries that implements certain educational reforms and programs together with the schools and institutions conducting national or international projects. The key distinctive features of a PS are as follows:

The PS introduces a new and different management and education model to the Turkish National Education System. The different education models that are adopted (intensive foreign language, physical sciences, or social sciences programs), the desire to integrate with international education societies (IB, IGCSE programs), and the authority and resources granted to the school management (building teaching staff, furnishing reports, and advisory board) are all regarded as steps for establishing a more efficient school. As long as the graduates of these schools achieve academic success and contribute to the society, it can be stipulated this education and management model be maintained and even popularized.

1.5. Program Diversity and Sustainability Studies in Project Schools

Program diversity is implemented in project schools to enable students to develop themselves in a field of their choice. With the variety of programs, students are encouraged to develop themselves by studying more intensively in the fields of science, social sciences, and foreign language. Other high schools provide education for four years while project schools offer five years of education [

56]. In the schools that implement the language project, English, German, Spanish, Russian, or Arabic is taught as a first foreign language and another as a second foreign language. During the training period, the students are sent to the countries where the languages they have learned are spoken. Kartal Anatolian Imam Hatip High School, one of the project schools, in terms of the number of students in IGCSE in school, is Turkey’s largest and most successful public school. Its IGCSE success in the last three years is 98.2% [

56].

In addition to the courses taught at the school, students at science and social sciences project schools receive academic support from universities. Two scientific workshops are held every week and one conference is held each month by academicians in the project school. Apart from the course materials, students read at least four books a year about their field and negotiate with their teachers. Students conduct scientific studies, experiments, examinations, travel, and observations. The project school model encourages students to learn through experience and produce more. That is to say, project schools are a new model for sustainable development. Students regularly attended projects in fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, ecology, history, and geography that were organized by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK). The number of scientific projects in the last five years has increased more than three times [

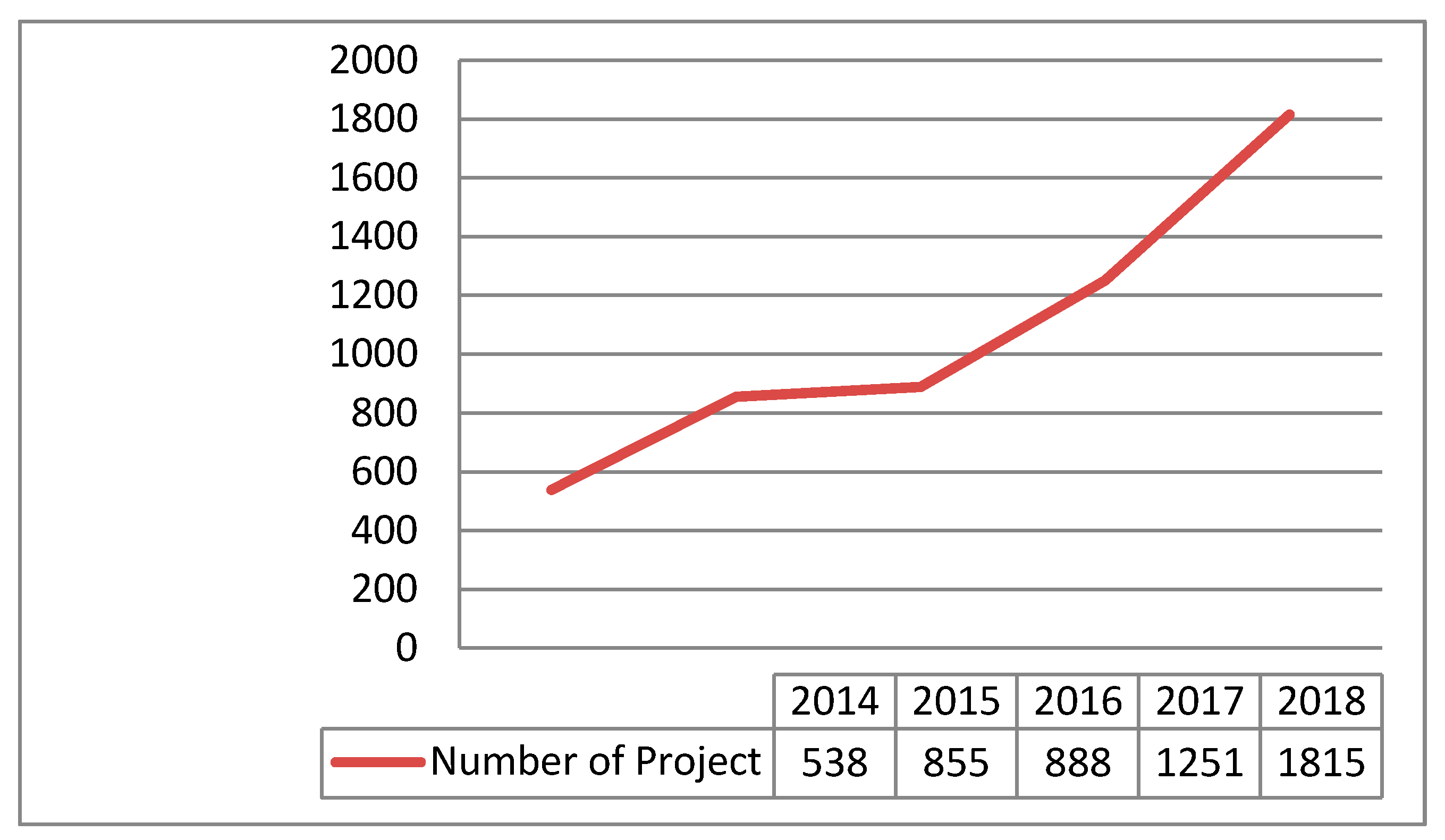

56].

Figure 2 shows the increase in the number of scientific projects in the five years since the project schools were established.

The fact that education in project schools is based on scientific projects, experiments, and observations is closely related to economic sustainability, because sustainable development can only be possible with potential financial benefits [

8] and production. Students carried out projects related to sustainability education such as producing their own electricity and STEM work with waste materials [

57]. In addition, the students organized the Sustainable Humanity Symposium [

58] and the International Istanbul Biology Student Symposium [

59]. Ecosystem sustainability was one of the main topics of this symposium.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Model

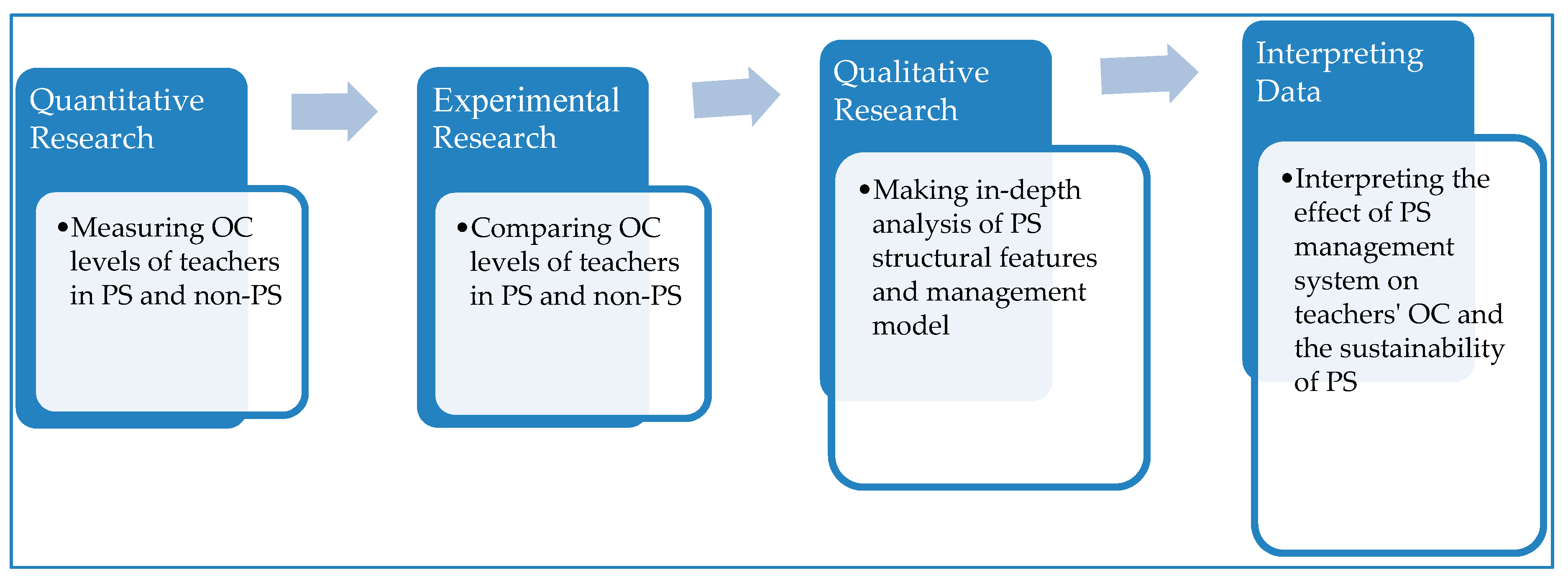

This research aimed at measuring the OC of teachers in PS offering religious education. It was conducted using a mixed method design model. Experimental research was carried out using a sequential mixed method that included scaling and interviewing (personal interview) techniques. A mixed method design means that quantitative research is first employed to collect and analyze data for the research topic, and then qualitative research is conducted to explain the quantitative results [

60], where the researcher draws conclusions based on the advantages of combining the two sets of data [

61]. In the initial phase of research, the teachers’ level of commitment was measured using a quantitative OC scale. The data obtained in the first stage was then analyzed in depth with the help of a semi-structured interview questionnaire.

A comparative experimental research model is a research method used to identify the characteristics of a certain problem and reveal the reasons for intergroup differences [

62]. Our research was conducted with teachers who had the same vocational competence and personal rights but who worked in different schools: PS or non-PS. The OC of the teachers in PS was the experimental group and was compared with the control group consisting of the teachers’ OC in non-PS. The experimental and control groups referred in this research are shown in

Table 1.

During our research, we examined whether the resources and authority granted to PS managers did or did not have a positive effect on teachers’ OC, examined teachers’ OC in non-PS, and then made a comparison between the two. The research model is shown in

Figure 3.

In the qualitative dimension of the research, the sustainability of PS, which is the research subject, was measured and analyzed in depth by examining the structural features of PS, the management model, school managers’ and teachers’ OC. In this part of the research, participants were given a semi-structured interview questionnaire.

2.2. Research Questions

Do the structural features and management model of PS create a difference in the education system?

Are the structural features and management model of PS sufficient for these schools to create their own tradition and be sustainable?

Do vocational development opportunities in PS create differences between teachers’ OC levels in PS and non-PS?

Does the feeling of being teammates in PS led by the principals’ building their own teams create differences between teachers’ OC levels in PS and non-PS?

Does the employees’ sense of justice and trust ensuing from their performance reviews in PS create differences between teachers’ OC levels in PS and non-PS?

Does the democratic management led by the teamwork in PS create differences between teachers’ OC levels in PS and non-PS?

2.3. Research Population and Sample

The research population consisted of all Imam Hatip Schools (IHL; Religious Vocational High Schools) in Istanbul that are PS and took place during the 2018–2019 school year. The experimental group included managers and teachers from PS IHL, and the control group included managers and teachers from non-PS IHL. Istanbul Provincial Directorate of National Education data showed that 8026 managers and teachers worked in IHL in Istanbul during that year.

For the quantitative dimension, 15 out of 55 PS IHL were chosen randomly for the experimental group, and 9 non-PS IHL were chosen randomly for the control group. In measuring the sample groups’ representative power of the research population, the confidence interval was accepted to be 0.01 and the margin of error was 0.05. Based on these figures, the minimum sampling size to represent the population of 8026 managers and teachers was calculated to be 370 [

63]. The obtained results showed that the representative power of the research sample consisting of 603 units can be said to be sufficient. The demographic characteristics of the participants included in the quantitative research are shown in

Table 2.

Thirty-seven managers and teachers were included in the qualitative dimension of the research: 23 from PS and 14 from non-PS. The demographic characteristics of the participants included in the qualitative research are shown in

Table 3.

2.4. Data Collection Instruments

To determine which data collection instruments to use, we reviewed the literature and related research. The OC scale developed by Üstüner [

64] has a one-factor structure with 17 items based on the findings obtained from exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. While this scale has a high positive correlation with MSQ, it has an average negative correlation with MBI. The internal consistency of the scale was found to be 0.96, and the test-retest correlation coefficient was 0.88. These results show that the scale is valid and reliable to measure teachers’ OC [

64].

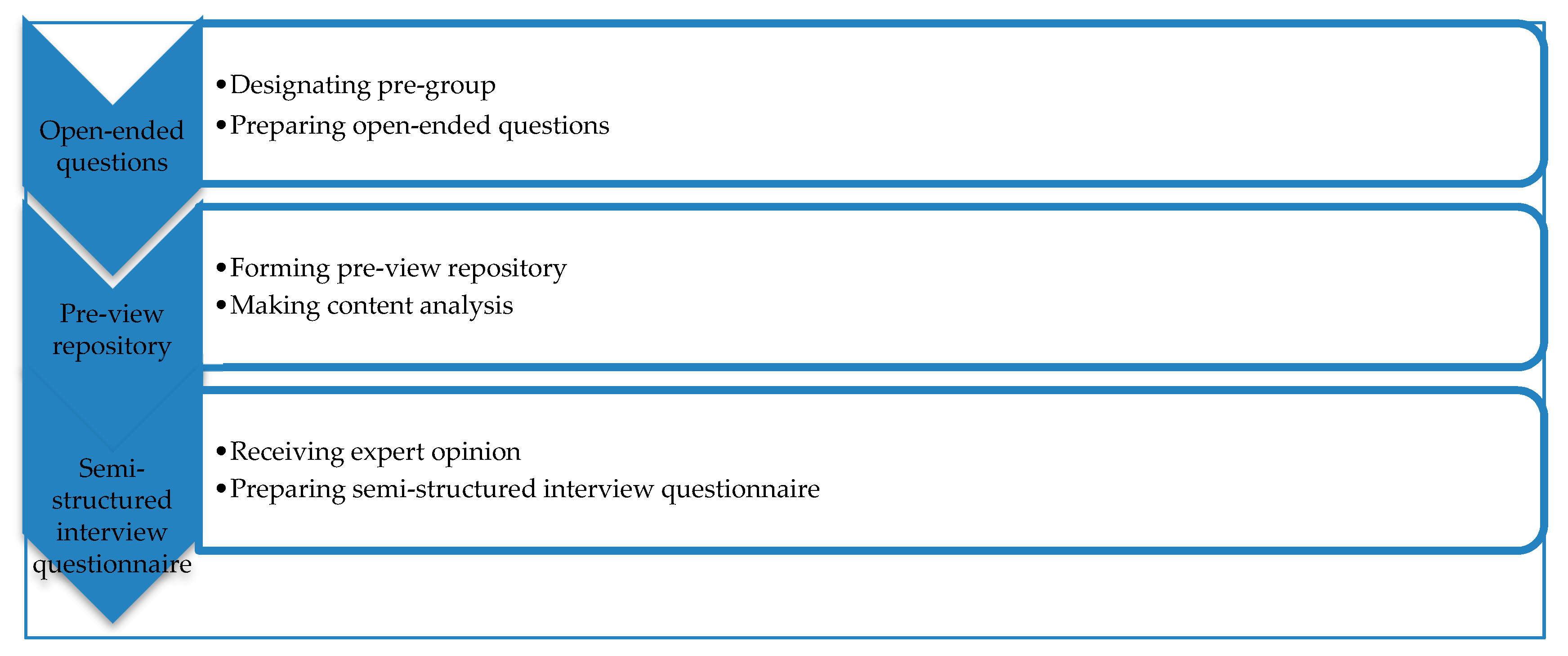

Before preparing the semi-structured interview questionnaire, the open-ended questions mentioned above were addressed to six participants who had similar features with the research group. The answers to these questions formed the pre-view repository and the data gathered from this repository were assessed in accordance with the content analysis. This was then used as a database for the semi-structured interview questionnaire. Finally, after receiving opinions from the field experts, we formed a semi-structured interview questionnaire with three questions:

How do you evaluate PS in terms of their distinctive features when compared to non-PS? Based on that comparison, what are the pros and cons?

How did the PS principal’s authority to build up a team and teachers’ limited length of service affect organizational behaviors in terms of OC, trust, and sense of justice?

Do you think structural features and management model of PS are enough for these schools to create a tradition and become sustainable?

The preparatory process of the semi-structured interview questionnaire is shown in

Figure 4.

2.5. Collecting Data

Data collection was done in Istanbul between 2 January 2019 and 8 March 2019. OC scales that were given permission for application before were delivered to the participants while we paid a visit to the schools. We handed them out during one-on-one interviews and we received their approvals at the same time. Data collection instruments were administered in these schools with the cooperation of school managers.

The interview method was used in the qualitative dimension of the research. We made appointments with participants before the interviews. Semi-structured interview questionnaires were also sent to all participants before the interviews. In all of the interviews, written approvals were received from participants. The interviews were also recorded and written notes were taken during the interviews. Interviews lasted from 16 to 53 min, with an average time of 27 min. Notes taken during the interviews, voice recordings, and the written answers of the participants were all resolved and subjected to content analysis.

2.6. Data Analysis

SSPS 25.0 was utilized for statistical analysis. In measuring teachers’ OC, arithmetic means were obtained. A five-point Likert scale used for the OC scale and score intervals corresponding to each option were determined. Here, when the rating is applied, the lowest score to be obtained from 17 items would be 17 and the highest score would be 85. A higher score implies higher OC and a lower score implies lower OC. In deciding whether or not the points obtained from the scale were high or low, the ratings described within a score interval were obtained by adding and subtracting standard deviations into the arithmetic mean as average: points lower than those were obtained by subtracting standard deviation from the arithmetic mean as low and points higher than those were obtained by adding the standard deviation into arithmetic mean as high [

64].

In this study, statistical methods compatible with every sub-problem were used. Reliability analysis was first conducted and then Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was calculated. For demographic factors with two groups, a t-test was applied. Intragroup differences were also observed. For factors with more than two groups, Levene’s test was first conducted to see if there was a homogenous distribution based on given answers, then ANOVA was administered to those with homogenous distribution and examined to see if there was any difference on intergroup 0.05 (95%) significance levels. In groups with differences, Tukey’s HSD test was applied. For groups with heterogeneous variances, the Brown–Forsyth test, an alternative of ANOVA, was administered as the difference test. For detecting groups who have differences in their significance level of 0.05, Tamhane’s T2 test was conducted.

In order to determine teachers’ OC, weighted mean and standard deviation values of the answers were calculated within the context of items and dimensions. Scoring was made to rate educators’ OC in non-PS and PS, which was one of the hypotheses being tested in this research. Points of answers were added and then arithmetic means were calculated by dividing the total into participant numbers according to the school types. In addition, the eighth item, “I feel myself completely a part of this school,” was accepted as the dependent variable in indicating OC, and together with other questions in the scale subjected to regression analysis. In this way, we rated the dimension of the relation.

The analysis of qualitative data was done using content analysis. In order to explain the collected data, content analysis aims at gathering similar data within the scope of certain concepts and organizing and interpreting them in such a way that readers can understand. We used the technique of coding for content analysis, which refers to researchers denominating parts to create a meaningful whole in itself with descriptive words or phrases [

65].

In qualified data analysis, persuasiveness and coherence are only possible if conciliation among coders is provided. Conciliation among coders is maintained through coding the gathered data by two or more researchers and checking coherency between these codings [

60]. Therefore, we can say that this research has a reliable result obtained by its qualified data analysis. In order to ensure the research’s validity, we referred to direct quotations of certain participants.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Dimension of the Research

The reliability analysis addressing teachers’ OC in PS and non-PS IHL was made and Cronbach’s Alpha was found to be 0.97. Such a value shows us that this research’s reliability is very high.

According to the research results, the teachers’ OC in PS IHL was high, exhibiting a level of 4.28. The teachers’ OC in non-PS IHL, however, was average, exhibiting a level of 3.81. Based on the statistical analysis, the OC levels of the participants are shown in

Table 4.

3.2. Comparing Qualified Data with Respect to School Type

The t-test we administered showed that there were differences in significance levels (95%) in relation to the answers to all questions by teachers in PS IHL and non-PS IHL. According to the school type, we saw homogeneity in answers given to the items 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 17 and the rest were not homogenous. The significance level was only 0.001 in the fourth item. The rest, however, exhibited a value of 0.000. Based on these results and the answers of groups, the difference in significance levels was 0.05 in terms of all related factors.

When teachers’ OC was evaluated according to school type, the OC of teachers in PS was high for four reasons:

PS contribution to their teachers’ vocational development.

The positive effect of the principals building their teaching staff on teamwork in schools.

The positive effect of performance reviews in PS on teachers’ sense of justice and trust.

The positive effect of democratic management in PS on teachers’ OC.

3.2.1. PS Contribution to Teachers’ Vocational Development

As a PS is development oriented and offers good vocational opportunities for teachers, it increases teachers’ OC in a significant way. The student profile and project-based education the PS presents have a positive effect on teachers’ OC. The results obtained from fifth and seventh question explain this and are shown in

Table 5.

Teachers in PS IHL gave maximum points to the seventh item. This reveals that teachers in PS have a strong belief in their school’s development-oriented structure. Considered the high points teachers gave to the fifth item, vocational development opportunities, we can say that working in PS has a positive effect on teachers’ OC. In addition, teachers in non-PS IHL gave lower points to the same item. So, we see a significant difference in perceptions of teachers working in both schools on their school’s development. This fact also influences their OC.

3.2.2. Positive Effect of Principals Building their Own Teaching Staff Based on Teamwork

The most important feature of a PS that distinguishes it from other schools is the principals’ ability to build their own teaching staff. This drives teachers to feel more attached to the school, causes a positive climate in the school, and motivates teachers to volunteer for more work. Based on the research results, we see that the cooperation between teachers and management in PS is stronger than it is in other schools. That may be tied to the effect of teachers’ selection by the principal. To clarify, it strengthens the team spirit and teamwork in these schools. The results that explain the situation are shown in

Table 6.

3.2.3. Effect of Performance Reviews on Teachers’ Sense of Justice and Trust in PS

Related literature shows that a strong sense of justice and trust in an organization has a positive effect on the organization climate and workers’ OC. Principals build their own teaching staff in PS, thus paving the way for a strong environment of trust and the performance reviews being more objective all appear to have a positive effect on teachers’ OC in PS. The results of the questions 2, 6, 10, and 13 that explain the situation are shown in

Table 7.

It can be argued that assigning the right jobs to the right people and making more objective performance reviews in PS increase teachers’ sense of trust and justice. To compare, in non-PS, the lowest mean is seen in the 13th item. Higher points being given to the same item in PS seem to indicate that reviews are made in PS according to performance, not the performer. As a result, reviews made according to performance have a positive effect on participants’ OC.

3.2.4. Effect of Democratic Management on Teachers’ OC

Democratic management in organizations increases workers’ OC. It can be argued that a high level of cooperation between teachers and the management in PS when compared to non-PS has a positive effect on teachers’ OC. According to the research results, teachers in PS feel that they are paid attention to more and collaborated with more than their colleagues in other schools. The results are shown in

Table 8.

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

Because the expression “I feel myself to be completely a part of this school” in the eighth item of the scale was accepted as an indicator of OC, it was chosen to be the dependent variable and added in the model. Accordingly, it was included in multiple regression analysis with other questions and their interrelation was measured. Therefore, a new model with 16 questions was created. This model explains 70% of change in participants’ OC. There seems to be a positive relationship between the factors and the OC. The regression analysis is shown in

Table 9.

The analysis shows that the factors showing participants’ commitment level as 0.05 were Items 2, 7, 9, 10, 12, and 17. These factors correspond to ones that show that the teachers’ OC increases in PS. They are as follows:

Item 9 (0.000). The research results show that we may argue that the support and encouragement offered by the management increased commitment more than other factors.

Item 10 (0.001) best explains the model. Feeling that organizational justice is provided also affects OC in a positive way and increases the level of commitment.

Items 2 and 17 (0.002) have the same value. This factor shows that a sense of trust and appreciation has a positive relationship with commitment. Their commitment-increasing effects come to the fore as an important matter.

Item 12 (0.003). This can be said to be an outcome of the OC rather than a cause of OC. We can argue that as much as the teachers’ commitment level increases, the teachers’ working rate without expecting material gains would also increase, provided that all other factors have materialized.

Item 7 (0.021). Belonging to a structure wherein people would gain personal benefits has a positive effect on commitment levels.

3.4. Qualified Dimension of the Research

In the research, managers were coded from M1 to M19 and teachers from T1 to T18. Themes and codes were formed according to the assessments of the participants’ answers to three questions in the semi-structured interview form. Accordingly, a total of 12 codes were created under three themes. Based on observations made during the research in schools along with the views of the participants, we see that 7 codes out of 12 affected PS sustainability in a positive manner, while five had a negative impact. In the research, we have given both the code frequencies and participants’ views.

3.5. First Theme: Effect of PS’ Features on PS Sustainability

While the quantitative dimension of this research revealed that the distinguishing features of PS affected teachers’ OC in a positive manner, the qualitative dimension proved their positive effect on PS sustainability. Among those distinguishing features, admitting students via exam, the positive image of PS, and vocational development opportunities in PS affect PS sustainability positively. On the other hand, teachers not getting paid or feeling that they are poorly paid for projects, courses, and events in PS are the basic factors that have a negative impact on PS sustainability, according to the interviews made in these schools. The first theme of the research’s qualified dimension is given in

Table 10.

3.5.1. Admitting Students via Exam

Thirty-three percent of teachers participating in the research said that teaching to students who have already gained self-discipline in studying even before they were admitted to the PS increases their job satisfaction levels and thus strengthens their OC and PS sustainability. While T5 said: “The school’s high-profile students have led me to love my job again”, T8 stated:

The most important factor in the PS is its high level and qualified students. Teachers are working in project schools because they want “an understanding student, a student easy to control”. That increases their job satisfaction level, makes them much happier here.

Numerous teachers reported that they reached their vocational peak in these schools. T10 said: “We reach our vocational peak here and thanks to its qualified students”, M19 similarly thought that his motivation and jobs satisfaction increased since students with similar levels and background are existing in PS together.

T11 reported “As the student profile is good here, I can do my job feeling happier and more excited. I can feel job satisfaction more.” T6 said “Being with good students makes me happy.” These and many other similar statements we heard during our interviews and observations considered together with the high-profile students in PS have led us to the conclusion that these features positively affect teachers’ job satisfaction, OC, and thereby PS sustainability.

3.5.2. The ‘Good School’ Image

A PS is perceived to be a ‘good school’ by teachers, students, and parents. It can be said that this very image positively affects both students and teachers. As one manager, M7, stated “PS are like merchants already making gains when purchasing.” Students who are already good enter these schools.” Another manager, M6, pointed to the gains of students and teachers due to the “good school” image by saying:

Our schools were perceived to be good schools even before they were declared as PS but that positive perception is now much better. Because being declared as PS has led the students to take more responsibility and teachers make more self-sacrifice.

Also, teachers’ feeling willing to make more sacrifices can be said to be directly proportional to teachers’ OC. In addition, it can be stated that having a high-level of ‘good school’ perception among students, teachers, and concerning environment backed by projects positively contributes to PS sustainability.

However, teachers warned that having too many PS would damage the ‘good school’ image and pose a threat to these schools’ sustainability. T3 said “Having too many PS decreases the quality.” T8 stated “I think PS can be sustainable if the number of these schools does not increase too much.” M6 said “It is too difficult for a PS to create a unique culture if the numbers are kept as high as they are. PS should have certain standards such as TSI.” Teachers are concerned about not having standards for opening a PS. According to these teachers, lacking standards would pave the way for over multiplying, thus over time turning PS into ordinary schools. M12 stated “Having too many PS reminds me of ‘unplanned urbanization,’ so that makes me think that the PS is not sustainable.” T16 said “The biggest problem of these schools is their numbers. It decreases its quality. With these numbers, it seems hard for them to create a tradition.” M17 stated “Regional PS must be built. The number of these schools should be decreased. If the number is to be kept this high, creating a unique tradition is not likely.”

3.5.3. Vocational Development Opportunities

Participants stated that having numerous applied projects in PS and benefiting from the guidance of university teachers who are members of their school’s advisory board and work either in those projects or courses with them contributes to their vocational development. According to M8, “Teachers exhibit serious vocational development during their works in PS. The administered projects contribute considerably to the teacher’s vocational development.” M6 said “Teachers from universities have started to come to the PS and attend classes and support projects. That seriously increased our quality.” Teachers also commonly stated that having many projects in schools offers opportunities for them and the students. T6 said “I feel that those works are also beneficial for me as well as students and I renew and improve myself.” Therefore, having more vocational development opportunities when compared to others positively affects teachers’ OC in PS.

3.5.4. Pay Policy

There are a large number of projects, events, and courses requiring more work hours in PS. Although teachers are paid for exam preparation courses, they are not paid for other events and projects in return of the work hours they spend. We observed that the features of PS positively influence teachers’ OC, and that impels teachers to make more sacrifice. That being said, this may not be the case for everyone. That is a fact of life. M6 said “We cannot cover teacher supply. Offering no compensation for extra work is the most important reason.” M8 suggested that “Job satisfaction needs to be supported with pay, points, and rewards.” M13 warned that “Teachers not getting extra pay in return for their hard work and projects would over time create a teacher shortage.”

3.6. Second Theme: The Effect of Principals Building Their Own Teams on PS Sustainability

We can claim that the authority that the PS principals are allowed to offer to their deputies and teachers by the Ministry of National Education is the most important feature that distinguishes PS from others. We can assert that the central administration’s decision to share authority, even though it is partial, has increased the general sense of teamwork among the staff working in PS. Among the codes we formed under the theme of “principals building their own teams”, voluntary work and team spirit seems to have a positive effect on teachers’ OC and PS sustainability. On the other hand, the lack of inspection and objective criteria in teachers’ selection and reviews have a negative effect on teachers’ OC and PS sustainability. The second theme of the research’s qualified dimension is exhibited in

Table 11.

3.6.1. Team Spirit

We have chosen the title team spirit, which can easily be replaced with family environment, sense of trust, or positive organization climate, as our research has shown that teachers in PS feel like they are an important part of the school. Almost half of the participants (49%) emphasized these feelings during our interviews. Numerous teachers and managers working in both PS and non-PS expressed a positive opinion about the idea of principals building their own teams. A teacher in a non-PS (T18) said “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Based on this idea, I think principals building their own teams is grand and would have substantial positive effect on the school environment.” The opinions of other teachers working in different PS are as follows: T2 said “The most important thing here is its ‘environment.’ We strongly feel the team climate here, and it is much easier to overcome problems as we deal them together.” T5 said “We make a good team here; I am very happy.” T6 said “I receive principals building their own teams very well. Team spirit positively affects job satisfaction.” One of the managers, M3, working in a PS looked at the issue of team spirit from the perspective of teachers: “The factions formed among teachers in other schools do not take root here in the PS, thus teachers and managers would be able to create a better team climate.” The idea of teamwork with each other in harmony is the intended target of PS and seems generally to be realized. That realization makes us claim that the PS is sustainable. Teachers’ statements also depict its positive effect on their OC levels.

3.6.2. Voluntary Work

During our research, we observed that due to a PS’s structure, teachers generally assume a warm approach towards tasks assigned by the management and projects and events organized in schools, thus are willing to work more and make more sacrifices. In addition, managers’ statements supported our observations. One of the PS managers, M3, shared a very interesting example:

A substitute teacher who came to work in our school for only two days has kept on coming to our school after his working hours and continued to be a part of students’ projects due to his heartfelt job satisfaction and commitment here. In our school, teachers do not rush to their homes at the end of their working hours; they prefer to stay here for a while, either with the students who stayed in school or do joint work or have meetings or talks with other colleagues.

3.6.3. Lack of Inspection

Principals building their own teams is welcomed in general. Nonetheless, there are some reservations on teachers’ selection and reviews. Participants stated that a more inclusive decision mechanism should be adopted. According to T10, “I think principals building their own teams and teachers’ performance are increasing competition. But a control mechanism should be in play.” T17 said “Principals should be asked why when they select and remove teachers. That is to say, a control mechanism is required.” T11 said “Lack of inspection in selecting teachers causes serious self-concern among teachers and sometimes damages the positive school climate.” As reflected by teachers’ opinions, we can say that a system depending exclusively on a principal’s decisions negatively affects teachers’ OC. Not having an inspection in a timely manner and/or not having a sufficient inspection pose a threat to PS sustainability.

3.6.4. Objective Criteria

One of three research participants (35%) stated that the principal should select and review teachers according to objective criteria, although they were quite satisfied to work with compatible teams in PS. Based on teachers’ views, it may be concluded that subjective decisions may decrease teachers’ OC and PS sustainability. T3 stated “While selecting teachers, objective criteria such as exams, experience, and career should be taken into consideration.” T10 said “For selecting and assessing teachers, objective criteria such as specialization should be followed and control mechanisms should be enabled.” T11 said “There should be more objective criteria in selecting teachers and that process should not be left to the principal’s initiative alone.”

3.7. Third Theme: The Effect of Limiting the Length of Service to Eight Years on PS Sustainability

One of the innovations brought with PS is limiting teachers’ and managers’ lengths of service to 4 + 4, or 8 years total. This limitation led to both approval and disapproval among participants. On the one hand, there are some who think the time limitation contributes to efficiency, increases performance, and maintains accountability, but on the other hand, some claim a PS will in time have difficulties finding qualified teachers with high levels of OC and lead to self-concern among their teachers. The third theme of the research is given in

Table 12. 3.7.1. Efficiency

Vocational blindness, defined as being unable to see flaws in tasks and workplaces due to long-time work in the same place and sharing a single environment with the same people, is accepted as an efficiency-decreasing factor. Making service limited and compulsory in order to avoid any diminishing productivity seems to be welcomed in general. It can be concluded that limitation would increase efficiency. M4 said “Making staff work for a limited period of time is a good practice because building a team with spirit becomes easier.” T7 said “Having a limited time of work makes it easier to build a team among teachers, and as a result both individual and organizational efficiency rises.” Nonetheless, there are differing views among participants. M17 said:

My opinion about limited length of service is as such: If the teacher is efficient and if the management, students, and parents are satisfied and sustaining their excitement, they should be allowed to work not 8 years but 18 years.

Based on our observations and interviews, we can argue that teachers approve limited length of service even though they have concerns and that it positively affects their OC. In addition, it provides stability and certainty in the workplace: teachers work in and with teams whose members are familiar.

3.7.2. Performance and Accountability

Participants stated that teachers’ limited length of service increases their performance and accountability in schools. T7 said “Team building and limited length of service definitely are among the factors increasing teachers’ performance.” T6 said “Accountability increases success and performance.” Performance reviews, particularly objective performance reviews, help to increase the sense of justice among school staff in general. It can be concluded that the limitation on length of service, which can be considered among initiatives aimed at increasing accountability in public institutions, has a positive effect on schools’ environment of trust and teachers’ sense of justice and OC in general.

3.7.3. Teacher Shortage

The eight-year limitation on length of service in PS mostly distresses school managers. Because teacher doing their jobs well can find work in other PS. However, it is not always easy to build a team whose members know each other well and have high OC. Managers referred to this situation as follows. M4 said:

Limiting the length of service is basically a good practice. But it takes time for a teacher to have a full command of educational programs, such as in foreign language education programs. And when they do, they are sent to other schools. That negatively affects our human resources.

M6 said “We experienced such difficulties due to the 4 + 4 limitation. We have had very efficient, experienced, and good teachers. But when their time expired, to our regret we lost and could not replace them.”

3.7.4. Self-Concern

While the limitation on length of service increases schools’ efficiency and teachers’ performance, it sometimes leads to self-concern among teachers. At this point, objective criteria can be considered as a factor for reducing self-concern. T11 said “When objective criteria are not applied in teachers’ reviews, teachers can have serious self-concerns about their years to come.” T10 said “I think principals building and reviewing their own teams increases competition. But while it increases performance, it can also have a negative effect on school environment, relations, and even the school’s progress.”

4. Discussion

In the literature, the concept of societal sustainability has been given importance [

7]. Societal sustainability focuses on social relationships, interactions, and human needs. For this reason, it is important that managers increase the quality of life in organizations, ensure social integration, and value universal human and employee rights. This research is focused on social integration in the dimensions of managers, teachers, students, and parents in project schools. It is also focused on the quality of life and education in project schools. The results show that project schools are more advanced than other schools in terms of social integration, quality of life, and education. Organizational sustainability includes improved employee morale, more efficient business processes, stronger public image, and increased employee loyalty [

38]. High moral values and loyalty of employees, strong organizational image, and more effective business processes are among the findings of our research. The structure of the PS is consistent with the sustainable organizational structure in the literature.

As expressed in the social sustainability model of the Western Australian Social Services Council, it is important that managers who want to ensure social sustainability create a family environment that values the principles of equality, diversity, commitment, democracy, and quality living in their organizations [

66]. In this research, the PS was examined using social sustainability criteria in terms of diversity, commitment, and democratic management. The findings show that PSs have a sustainable organizational structure in terms of the diversity and commitment of teachers and the democratic nature of the administration.

Having teamwork, maintaining employee participation, keeping intra-organizational communication channels open, evaluating employee performance based on objective criteria, and thus getting positive worker output would clear the way for sustainability [

45,

46,

47]. In the literature, teamwork, intra-organizational communication, and performance evaluation, which are posited to open the way for sustainability, are applied in PSs. According to the results of this research, it is seen that the practices in PSs have a positive effect on teachers’ productivity, school quality, and sustainability.

The further development of the talents of the individuals with ability will ensure the sustainability of the organizations and pave the way for more productive individuals in society [

67]. In the PSs, scientific projects for students to learn by themselves enable teachers to develop themselves. With this feature, PSs are separated from other schools and thus reach their organizational goals more easily.

Johnson and his colleagues considered in-organization partnerships and cooperation an important factor for sustainability [

47]. This study shows that the participation of teachers in decision-making processes in PSs and continuous exchange of ideas between teachers contribute to the organizational sustainability of these schools. Performance evaluation in human resources practices can contribute positively to social sustainability, because one of the objectives of employee performance management is to pave the way for employee development and thus ensure human sustainability [

48]. There have also been similar findings in terms of a positive relationship between environmental sustainability and organizational commitment. Tilleman states that a collectivistic organizational identity orientation including organizational commitment is possible when a company works toward a greater good such as environmental sustainability [

19].

PSs are schools where performance evaluation is being done for the first time in public schools. The positive findings on this issue are consistent with the literature. This result indicates that performance evaluation will contribute to the sustainability of PSs.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This research aimed to compare OC levels of teachers working in PSs and non-PSs and measure PS organizational sustainability. Based on the results, we can claim that OC levels of teachers in PSs are higher than teachers in non-PSs. Therefore, the argument that structural features of the PS increase teachers’ OC; hence, their performance is correct: its management model is appropriate. The most effective factors that help increase teachers’ commitment are the ‘good school’ image of the PS and its teachers’ job satisfaction and development opportunities. Accordingly, admitting students who already have self-discipline in studying seems to increase PS teachers’ job satisfaction and development levels hence their OC levels.

PS principals building their own teams and attaching particular importance to teamwork have positive effects on teachers’ self-determination at work and their OC. This causes a serious increase in teachers’ willingness to volunteer for work in the PS without expecting any extra pay. Teachers state that they cooperate with the school management to a large extent. While a principal’s authority to select teachers has positive effects, there are some important concerns regarding the execution of that authority. The need for objective criteria for teacher selection and reviews and an operating control mechanism are among the most important concerns mentioned by the research participants. Despite these concerns, principals building their own teams is very well received by teachers in both PSs and non-PSs. In addition, the qualified and quantified dimension of the research confirmed the same conclusion.

The maximum eight-year limitation on teachers’ length of service working in PSs seems to have positive effects on teachers’ performance. That limitation is considered to be helpful in building a harmonized team. It can be said that this feature of the PS contributes to teachers’ OC. However, while managers have concerns about replacing teachers when their service ends, teachers have self-concerns about losing the family environment in a PS and finding a similar team spirit in their next schools. In this respect, limited length of service seems to need re-thinking for the sake of PS sustainability.

The PS seems to have brought a new excitement and offered a new horizon to the Turkish national education system. In this respect, we can claim that these brand new schools will make a difference in time, so they should be sustained. For the PS to easily achieve its goals and be sustainable, we make the following recommendations based on the participants’ views:

Strengthening the ‘good school’ image of the PS by applying objective criteria and bringing standards for PS opening and management, maintaining the student and teacher quality by limiting the number of PSs, and supporting PSs through legislation and auxiliary staff to help them become schools with unique targets and projects, almost as if they were ‘boutique PSs’, would contribute to PS sustainability.

Since a PS principal’s authority to select teachers has a positive effect on the school and its teachers, we think it would be wise to sustain that application. However, more objective criteria for selecting teachers need to be established. Pools can be built for teachers, comprising such things as their qualifications, such as centralized examinations, academic adequacy, and experience, and also for schools, comprising such things as their education models, physical environment, social opportunities, and national/international projects. After a while, they can be allowed to select each other.

Granting financial incentives to teachers for their involvement in school projects and events on a project basis would increase both the quality of projects and OC of teachers. This would also be beneficial for maintaining PS sustainability.

The maximum eight-year limitation on length of service in a PS has both positive and negative effects. It facilitates team building and averts vocational blindness but leads to pressure and self-concern among teachers. It would be pertinent to do more field research on PSs to get clearer conclusions about the effects of limiting length of service on schools and teachers’ OC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, A.K; validation, A.K.; investigation, A.K.; resources, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, M.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Y. Examining organizational citizenship behavior of Japanese employees: A multidimensional analysis of the relationship to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: An Examination of Construct Validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 49, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastas, M.; Öztuğ, Ö. Öğretmenlerin Örgütsel Adalet Konusundaki Algılarının Örgütsel Bağlılıkları Üzerindeki Etkisi. Hacet. Üniv. Eğitim Fak. Derg. 2012, 2, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kell, H.J.; Motowidlo, S.J. Deconstructing Organizational Commitment: Associations Among Its Affective and Cognitive Components, Personality Antecedents, and Behavioral Outcomes1: DECONSTRUCTING ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 213–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Session, S.W. World commission on environment and development. In Our Common Future; WCED, Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, economy and society: Fitting them together into sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.M.; Scavarda, A.; Hofmeister, L.F.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Vaccaro, G.L.R. An analysis of the interplay between organizational sustainability, knowledge management, and open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvare, R.; Johansson, P. Management for sustainability—A stakeholder theory. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2010, 21, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, A. Sürdürülebilirlik Raporları. Muh. Vergi Uyg. Der. 2012, 5, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- BIST, B.İ. Şirketler İçin Sürdürülebilirlik Rehberi. Available online: http://www.borsaistanbul.com/data/kilavuzlar/surdurulebilirlik-rehberi.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2019).

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental Sustainability at Work: A Call to Action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S. The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4051-6402-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Green Organizations: Driving Change with I-O Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-203-14293-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, K.J.; Steimle, U.; Fischer, K. Human Factors, Business Excellence and Corporate Sustainability: Differing Perspectives, Joint Objectives. In Corporate Sustainability as a Challenge for Comprehensive Management; Zink, K.J., Ed.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-3-7908-2045-4. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Z.; Van der Merwe, D. Innovative management for organizational sustainability in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgül, B.; Gürol, Y. Content Analysis over Role of Sustainable Human Resources Management in Corporate Sustainability. J. Dogus Univ. 2016, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management (Contributions to Management Science); Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-7908-2187-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tilleman, S. Is Employee Organizational Commitment Related to Firm Environmental Sustainability? J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2012, 25, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, N.L.; Lambert, E.G.; Griffin, M.L. Loyalty, Love, and Investments: The Impact of Job Outcomes on the Organizational Commitment of Correctional Staff. Crim. Justice Behav. 2013, 40, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devece, C.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Pilar Alguacil, M. Organizational commitment and its effects on organizational citizenship behavior in a high-unemployment environment. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balay, R. Yönetici ve Öğretmenlerde Örgütsel Bağlılık; Nobel Yayınları: Ankara, Turkey, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Biskin, H. Examination of organizational commitment levels of physical education and sports teachers according to various variables (case study of Kutahya province). Turk. J. Sport Exerc. 2014, 16, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, M.P.; Gupta, M. Impact of procedural justice perception on team commitment: Role of participatory safety and task routineness. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2015, 12, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, M.; Portoghese, I.; Coppola, R.C.; Finco, G.; Campagna, M. Nurses well-being in intensive care units: Study of factors promoting team commitment: Nurses well-being in ICUs. Nurs. Crit. Care 2016, 21, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wombacher, J.C.; Felfe, J. Dual commitment in the organization: Effects of the interplay of team and organizational commitment on employee citizenship behavior, efficacy beliefs, and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. Antecedents of organizational commitment across occupational groups: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrasch, A.I. Antecedents and Consequences of Organizational Commitment. Mil. Psychol. 2003, 15, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, U. Örgütsel Iletişim ile Örgütsel Bağlılık Arasındaki Ilişkisellik-Bir Yükseköğretim Kurumu Olarak KTMÜ Uygulama Örneği; Lisans, Y., Ed.; Manas Üniversitesi: Biskek, Kırgızistan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Faraji, M.; Begzadeh, S. The Relationship between Organizational Commitment and Spiritual Intelligence with Job Performance in Physical Education Staff in East Azerbaijan Province. Int. J. Manag. Account. Econ. 2017, 4, 565–577. [Google Scholar]

- Sabuncuoğlu, E.T. Eğitim, örgütsel bağlılık ve işten ayrılma niyeti arasındaki ilişkilerin incelenmesi. Ege Akad. Bakış Der. 2007, 7, 613–628. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, M.; Uçar, İ.H. Öğretmenlere Göre İlköğretimde Öğrenen Örgüt Algısı ve Öğrenen Örgütün Örgütsel Bağlılığa Etkisi. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2013, 13, 1515–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Chih, W.-H.; Lin, Y.-A. The study of the antecedent factors of organisational commitment for high-tech industries in Taiwan. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2009, 20, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Minor, K.I.; Wells, J.B.; Hogan, N.L. Social support’s relationship to correctional staff job stress, job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Soc. Sci. J. 2016, 53, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şirin, E.F.; Dalkıran, E. The relation between organizational commitment and managerial effectiveness of instructors at schools of physical education and sports. Turk. J. Sport Exerc. 2017, 19, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sancar, G. Kurumsal Sürdürülebilirlik Bağlamında Kurumsal Yönetişim: Kavramın Doğuşu, Gelişimi ve Değerlendirilmesi. Selçuk Üniversitesi Ilet. Fakültesi Akad. Derg. 2013, 8, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Veiga, J.F. Putting people first for organizational success. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1999, 13, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L.; Haunschild, A.; Matten, D. The rise of CSR: Implications for HRM and employee representation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-F.; Wang, J.-J.; Lin, T.-J. Resource sufficiency, organizational cohesion, and organizational effectiveness of emergency response. Nat. Hazards 2011, 58, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Pedrini, M. The consensus between Italian HR and sustainability managers on HR management for sustainability-driven change—Towards a ‘strong’ HR management system. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1787–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesen, M. İşletme Yönetiminde Sürdürülebilir İnsan Kaynakları Yönetiminin Yeri ve Önemi. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. Res. 2016, 554–573. [Google Scholar]

- Genç, H. Toplam Kalite Yönetimi Dahilinde Hasta Memnuniyeti. Yüksek Lisans Tezi; Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İşletme Fakültesi: Sivas, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Sánchez, A.; Barba-Aragón, I.; Sanz-Valle, R. Effects of training on business results. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2003, 14, 956–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, N.; Zaugg, R.J. Nachhaltiges und innovatives Personalmanagement. In Nachhaltiges Innovationsmanagement; Schwarz, E.J., Ed.; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; pp. 215–245. ISBN 978-3-663-10863-4. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.; Hays, C.; Center, H.; Daley, C. Building capacity and sustainable prevention innovations: A sustainability planning model. Eval. Program Plan. 2004, 27, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Ramstad, P.M. Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlall, S.J. Enhancing Employee Performance Through Positive Organizational Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 1580–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, O.A.; Beisler, J.M.; Keel, J. Current Trends of Unethical Behavior Within Organizations. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 19, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, N.V.; Goldbach, I.; Goldbach, F. Relationships between human resources management and organizational culture. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Information Management and Evaluation, Como, Italy, 8–11 September 2011; pp. 486–496. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, N.; Ergün, E.; Kesen, M. The Effects of Human Resource Management Practices and Organizational Culture Types on Organizational Cynicism: An empirical study in Turkey. Br. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2014, 17, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dağhan, G.; Akkoyunlu, B. Modeling the continuance usage intention of online learning environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgül, B.; Mengi, B. Kurumsal Sürdürülebilirlik ve Güvencesi, İç Denetim; Beta Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Ministry of National Education. Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı Özel Program ve Proje Uygulayan Eğitim Kurumları Yönetmeliği,. Kanun no: 29818. md.6; Resmi Gazete: Ankara, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DOGM, Turkish Ministry of National Education. Project Schools Introduction Booklet; Turkish Ministry of National Education: Ankara, Turkey, 2018.

- DOGM, Turkish Ministry of Education. Project Schools Almanac October–December 2018; Turkish Ministry of National Education: Ankara, Turkey, 2019.

- Kartal Anatolian Imam Hatip High School. Sustainable Humanity Symposium; Kartal Anatolian Imam Hatip High School: İstanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Şehit Adil Büyükcengiz Anatolian Imam Hatip High School. Sustainability of Ecosystems. International Istanbul Student Biology Symposium; Şehit Adil Büyükcengiz Anatolian Imam Hatip High School: İstanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, W. Karma Yöntem Araştırmalarına Giriş; Pegem Akademi Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, J.R. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education; McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Büyüköztürk, S. Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemleri; Pegem Akademi Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Üstüner, M. Teachers’ Organizational Commitment Scale: A Validity and Reliability Study. Inonu Univ. J. Fac. Educ. 2009, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Sosyal Bilimlerde Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri, 10th ed.; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, V.; Garavan, T.; Sadler-Smith, E. Corporate social responsibility, sustainability, ethics and international human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2014, 17, 497–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).