1. Introduction

The composition of the average classroom is changing as a result of world-wide human mobility. In recent decades, the proportion of students with at least one parent who had migrated across international borders, or who had themselves done so, has grown by an average of six percent across all member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [

1]. For example, more than half of school-age youth are members of ethnic minority groups in the United States of America for the first time in history. In particular, Latinos are the largest ethnic minority group [

2].

In Spain (Europe), the percentage of students of foreign origin has increased from 1.4% (in 1999–2000) to 8.8% (in 2018–2019), with the autonomous community of Catalonia being the region with the highest percentage of students of foreign origin (13.2%), mainly, from African countries, the European Union and the South America [

3].

The challenge we face is illustrated by the data showing a learning gap due to migrant condition. In line with previous studies, the latest Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) report has shown statistically significant differences in reading, science and mathematics learning competencies between young students (15 years old) with a migrant background and those without. Moreover, these differences in learning outcomes remain significant even when taking into account the language spoken at home and the family’s economic, social and cultural status (ESCS), as shown in

Table 1, in the case of science competencies. Neither familiarity with the local language nor the family’s socioeconomic status is enough to account for these differences in academic performance [

4]. Furthermore, not only do these disadvantaged students obtain lower scores, but they are also more likely to arrive late for school, show signs of disengagement, skip classes or skip school altogether [

1,

2,

3,

4].

One of the most common explanations of the learning gap between migrants and non-migrants involves the problem of deficit thinking in education, which stems from the notion that students of foreign origin or from minorities fail at school because they and their families experience deficiencies in terms of poor home socialization, language skills and cultural artifacts, which in turn hinder the students’ learning process [

5].

In a direct challenge to this way of thinking, the funds of knowledge approach emerged in the southwestern region of the United States of America (Tucson, Arizona State) as part of a range of social justice efforts in education aimed at making the curriculum and learning more equitable and engaging for students from historically marginalized communities. It was based on the premise that all students and families are valuable and accumulate knowledge, skills and cultural resources [

6,

7].

In this context, ‘funds of knowledge’ refers to the accumulated skills and cultural practices that enable families to function in their everyday lives within a given socio-cultural context [

6]. For example, a particular house could be considered a repository of diverse funds of knowledge, such as multilingual competence, mathematic knowledge or art skills, derived from their lived experiences and activities at work or in the community. The challenge is to use these funds of knowledge pedagogically to improve learning [

8].

To this end, teachers visit the homes of some of their students in order to empirically document their particular funds of knowledge so that they can then be used, pedagogically, in the context of the classroom, while at the same time developing collaborative relationships with the families based on mutual trust. In these ethnographic visits, teachers ask about the history of the family, in particular their work history, hobbies, activities and interests, literacy practices and so on, thus revealing the accumulated funds of knowledge within the household. For example, rich bodies of knowledge and skills have been identified among families of Mexican origin living in the state of Arizona: with material and scientific knowledge connected to construction (carpentry, roofing, masonry, painting, design and architecture), ranching and farming (including horse riding skills), mining (knowledge of timbering, minerals, blasting), repair (automobile, airplanes, tractors), economics and business, medicine, household management and religion [

6].

Once identified, teachers incorporate these skills and know-how into classroom activities, thus establishing links between the funds of knowledge accumulated by these families and the school curriculum and teaching practice. For example, a natural science teacher in a primary school used one father’s occupation in agriculture to develop learning objectives such as classifying animals according to what they eat [

9].

Several literature reviews have illustrated the significant benefits of this educational approach in at least three areas: a) improving academic performance by boosting significant learning as a result of connecting in-school and out-of-school learning experiences, b) improving family-school relationships by combating stereotypes and prejudices and c) improving and transforming educational practice towards more innovative pedagogical strategies that allow the curriculum to be contextualized [

10,

11].

However, there are certain constraints and limitations to the funds of knowledge approach which can make it difficult to put into practice and reduce its efficacy. Three problems in particular have been identified: (i) Implementing this approach requires time. In any given classroom, the teacher can only focus on a limited number of the students and their families. (ii) There is lack of specific focus on the learner while so much attention is on the families and their knowledge and abilities [

12]. (iii) Finally, only qualitative strategies and techniques are used [

13].

In order to overcome these limitations, the concept of ‘funds of identity’ has been developed [

12,

13,

14]. This concept places the emphasis on the students’ lived experiences, identities and meaningful activities. Pedagogically, it is based on the use of “identity artifacts” [

15], that is, texts, drawings, pictures or other cultural tools made by the learners which can be incorporated in school by teachers to connect the curriculum with students’ lives. In this sense, funds of identity are understood to comprise those people, spaces, things and activities that, for the learners, are the most important and most relevant, and which, ultimately, best define them. They may involve significant people, such as partners or family (‘social funds of identity’), spaces or places such as a city, a mountain or the sea (‘geographical funds of identity’), institutions such as the Catholic Church or the Muslim religion (‘institutional funds of identity’), interests and activities (‘identity practices’) or cultural artifacts such as a flag, a mobile phone or a musical instrument (‘cultural funds of identity’) [

14].

In order to elicit the learners’ funds of identity, the teacher can use, for example, graphic-visual techniques such as ‘identity drawings’ which involve learners being asked to represent, in a drawing, those aspects which they believe best define them, or are most important and relevant to them [

13]. Once identified, these funds of identity—the aspects of their lives that make most personal sense to the learners—are then linked by the teacher to the school curriculum and educational practice [

9]. To give a simple example, funds of identity linked to comics were used to facilitate and improve the learning of Spanish [

16].

This conceptual and educational intervention approach is closely related to the culturally sustaining pedagogy that “seeks to perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” [

17] (p. 41). The purpose is not only legitimate cultural practices of students and their families, but also to guarantee the existence of these legacies in educational practice, in particular, and society, in general. It involves challenging the dominant values and classroom norms that position minority languages and identities as “less-than” or inferior and unworthy of a place in school practices. It is in that regard that we talk about sustaining students’ identities as a democratic and social justice purpose of school to make visible, legitimate, recognize and maintain (in one word: sustain) the multi-ethnic and multilingual societies described above. Hence, the term culturally sustaining pedagogy refers to a theoretical approach and an educational action that supports students in sustaining and revitalizing the value of their communities while simultaneously looking forward in order to promote the skills and knowledge needed to participate in our changing societies.

The main research question of this study was: how can school practice sustain students’ cultures using the funds of knowledge and funds of identity approaches? We describe two empirical examples from studies conducted in two different educational settings in Catalonia, Spain. One of them focuses on the funds of knowledge of the students’ families, the other, on the funds of identity of the students themselves. The general aim is to empirically illustrate methodologies that put culturally sustaining pedagogies into practice.

2. Materials and Methods

The study reported here was informed by the Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodology based on the assumption of the impossibility to separate the creation of knowledge, obtaining data and action-intervention research [

18]. It is a way of conceiving research and intervention as a bidirectional process where participation in the process is considered an opportunity to promote the understanding and changing of any social reality with the final purpose of transforming it collectively. According to the PAR, there is no separation between researcher and participant; it is only through the interaction between both that investigation-research-intervention is possible. It is a methodological strategy to legitimate social and cultural practices as an element to generate scientific knowledge through fostering change, both in the situation (educational practice, in our case) and in the participants and researchers, as a result of a continuous process of action-reflection [

19].

In particular, the funds of knowledge approach described above is based on the creation of study groups [

20,

21]. This consists of a community of practice composed of teachers and university researchers who discuss and share their knowledge collaboratively in order to link the analysis of students’ homes (via ethnographic visits and in-depth interviews) with the development of educational practices that could capitalize on and legitimate the funds of knowledge identified.

Ethical approval for conducting this intervention-research was provided by the ethical committee of the University of Girona. All participants in this study (teachers, families and students) took part voluntarily and agreed to sign a document of informed consent giving their permission to publish photographs, videos and other information resulting from this research. It should be noted that the families were expressly informed that the aim of the home visits and interviews was to learn from the students and their families; the teachers were not there as “experts” but as “learners”. Careful and sensitive communication with the students and their families is an indispensable element of this approach.

2.1. Participants and Context of the Intervention-research

Two education centers in Catalonia (Spain) participated in the study. The selection criteria used to choose the participating centers are given in

Table 2.

The educational project was presented, in each education center, to the management team and in a meeting of the school’s staff. After agreeing to participate, the study groups were set up, being made up of teachers who showed interest and who voluntarily agreed to implement the educational program.

In Context A (funds of knowledge intervention-research), the participants included five teachers (between 28 and 53 years old; mean age 38), the head of studies (54 years old) and the head teacher (55 years old), of a public school in the province of Girona, together with two research professors (35 and 38 years old) from the Culture and Education research group of the University of Girona, both experts in the funds of knowledge approach. Hence, the study group was formed by nine people in total, eight women and one man. The educational center itself was created in 2012 in a locality in the province of Girona of less than 20,000 inhabitants and, in the 2018-2019 academic year, 30 percent of the students were of foreign origin, mainly from Morocco, Gambia and China. More specifically, the five families that participated in the project originated from Morocco, Mali, Gambia and China. It was the teachers themselves, in the context of the study group, who decided which families to interview based on two criteria: that the students involved were not performing well at school, and that there was, as yet, a lack of knowledge or little contact between the teachers and the families of these students. In the section on procedure, we describe the phases of implementation of the project in this educational center.

Context B (funds of identity intervention-research) involved two classes in a school in the city of Barcelona: the participants included (i) 25 students aged 12 years old, one teacher aged 37 years old and three researchers (from 24 to 27 years old); and (ii) 18 students aged 13 years old, two teachers aged 24 and 35 years old and four researchers (from 24 to 30 years old). The school is situated in a lower-middle class suburb of Barcelona. Specifically, in these two classes, 50 percent of the students were Roma. Among the rest of the students, those who were of foreign origin had migrated (or their families had migrated) from the following countries: Morocco, Pakistan, Honduras, Bolivia and China. Since 2017, the school has been transformed into a new center, with project-based learning, collaborative work and a large number of alliances with entities in the immediate environment. The research group DEHISI [Human Development, Social Intervention and Interculturality], at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, accompanied the center in this transformation, with the participation of researchers and students, and collaborated with the teachers as well as with Roma educators from community organizations. The project consisted of the development of communities of practice in the primary and secondary school, following the Fifth Dimension model and, in the last year, the incorporation of FdC [continuous teacher training] projects in preschool and FdI [institutional development fund] in the secondary school.

It should be noted here that both educational contexts are characterized by their social and cultural diversity (at least 30% of students being of foreign origin). According to official data, the percentage of students of foreign origin in schools across Spain was, for the 2018-2019 academic year, 8.8%, although the autonomous community with the highest percentage of students of foreign origin was Catalonia, with 13.2% [

3].

2.2. Instruments

Funds of knowledge interview. Based on the interview used in the funds of knowledge approach developed at the University of Arizona, a shorter version, adapted to the local situation, was created. With the aim of encouraging the teachers to take control of the methodology used, it was the teachers themselves who, in the framework of the study group, selected the questions that seemed most relevant to them in order to document the families’ funds of knowledge. In the end, a six-part version was drawn up that asked about the socio-cultural structure and practices of the family. Specifically, there were questions about family structure, work experiences and history, literacy practices, languages used, hobbies, religion, education and ethnic identity. The researchers collaborated in this process of adapting the interviews, guaranteeing that the reduction in the number of questions would not impair the objectives of each section of the original interview. In this sense, all the sections that appeared in the original version were represented in the version used.

Meaningful circle. This consists of a graphical representation of people, activities, artifacts, places that the participant finds meaningful. It is based on relational mapping [

22]. The version used follows the statement: “Write down the people, activities, things or places that are most meaningful to you in a big circle. Write inside some smaller circles the most significant people and write inside a small square activities, things or places. Keep in mind that the closer to the center of the big circle you put the small circles and the squares, the more important they are to you.”

Artist’s book. This is a six-page individual book in which each student can express and reflect themselves through multiple techniques including collage, drawing, comics, painting or even writing. The objective is to create their own narrative of “who I am”, “what defines me” or “the most important things in my life”. It is one of the latest among a range of techniques used to elicit narratives on students’ identities through artistic productions (

Figure 1).

2.3. Procedure

Given that the object of study and intervention was different in both contexts (family funds of knowledge, in one case, and student funds of identity, in the other), different phases of implementation were developed in each context and these are described below.

Context A (the funds of knowledge research-intervention):

In line with previous studies and interventions [

7,

20], having first presented the research-intervention project to the management team and the teaching staff, and having set up the study group with teachers who freely decided to be part of it, four phases were planned in order to implement the funds of knowledge approach. All four phases were implemented with no substantial changes made to them. The first phase, the training phase, took place over three sessions, each lasting an hour and a half, during which the study group read about, and discussed, other experiences based on the funds of knowledge approach [

7,

8] in order to familiarize themselves with the basic theoretical and methodological aspects. Specifically, in the first and second sessions, each teacher looked into another previous experience and then described it to her colleagues. From the various case studies, and with the help of the researchers, the teachers worked on various aspects involved in the approach, in terms of theory (for example, the notion of funds of knowledge) and method (for example, how to carry out the visits). In the third session, the revised version of the interview to be used in the home visits was developed collectively. The second phase consisted of carrying out the field work, i.e., the home visits. Over a period of one month, a total of five families were visited. In the third phase, again within the framework of the study group, educational activities were designed that were based on the funds of knowledge identified. Finally, having used these activities in the classrooms, the fourth phase consisted of evaluating the program by identifying the strengths, limitations and areas for improvement of the approach, according to the perceptions and experiences of the participating teachers.

Context B (the funds of identity research-intervention):

In this case, the educational research-intervention consisted of the following four phases: teacher training, design of the activities, implementation and evaluation. Since, in this case, the focus of analysis, study and intervention was on the students and their funds of identity rather than the family and their funds of knowledge, there was no phase involving home visits. Instead, we moved directly to familiarizing the participant teachers with the concept of funds of identity, and the creation and implementation of educational activities. The first phase, aimed at discussing the concept of funds of identity, consisted of a session lasting an hour and a half with the teaching staff and the management team of the educational center. In the second phase, researchers proposed the intervention to the teachers, who agreed and collaborated in the design of the activities. The third phase was carried out in seven sessions (one per week). In the first session, we introduced the activity to the students and they created their meaningful circle. During the next three sessions, we designed different activities based on funds of identity: identity practices, social, geographical, cultural and institutional funds of identity. Students had three modalities of activity to choose from: activities that involved creation and expression through plastic arts, through literacy and poetry and through theatrical performance. In the last three sessions, students focused on the creation of the artist’s book described above. Finally, the evaluation involved the students (self-evaluation and evaluation of the activities of this research-intervention), as well as teachers and researchers (discussion group to evaluate, collectively, the intervention carried out).

3. Results

We have divided the results into two sections that correspond to the two educational research-interventions: (3.1) The results obtained from the funds of knowledge research-intervention (context A described above); (3.2) The results generated from the funds of identity research-intervention (context B described above).

3.1. Families’ Funds of Knowledge Go to School. The Case of Peanuts

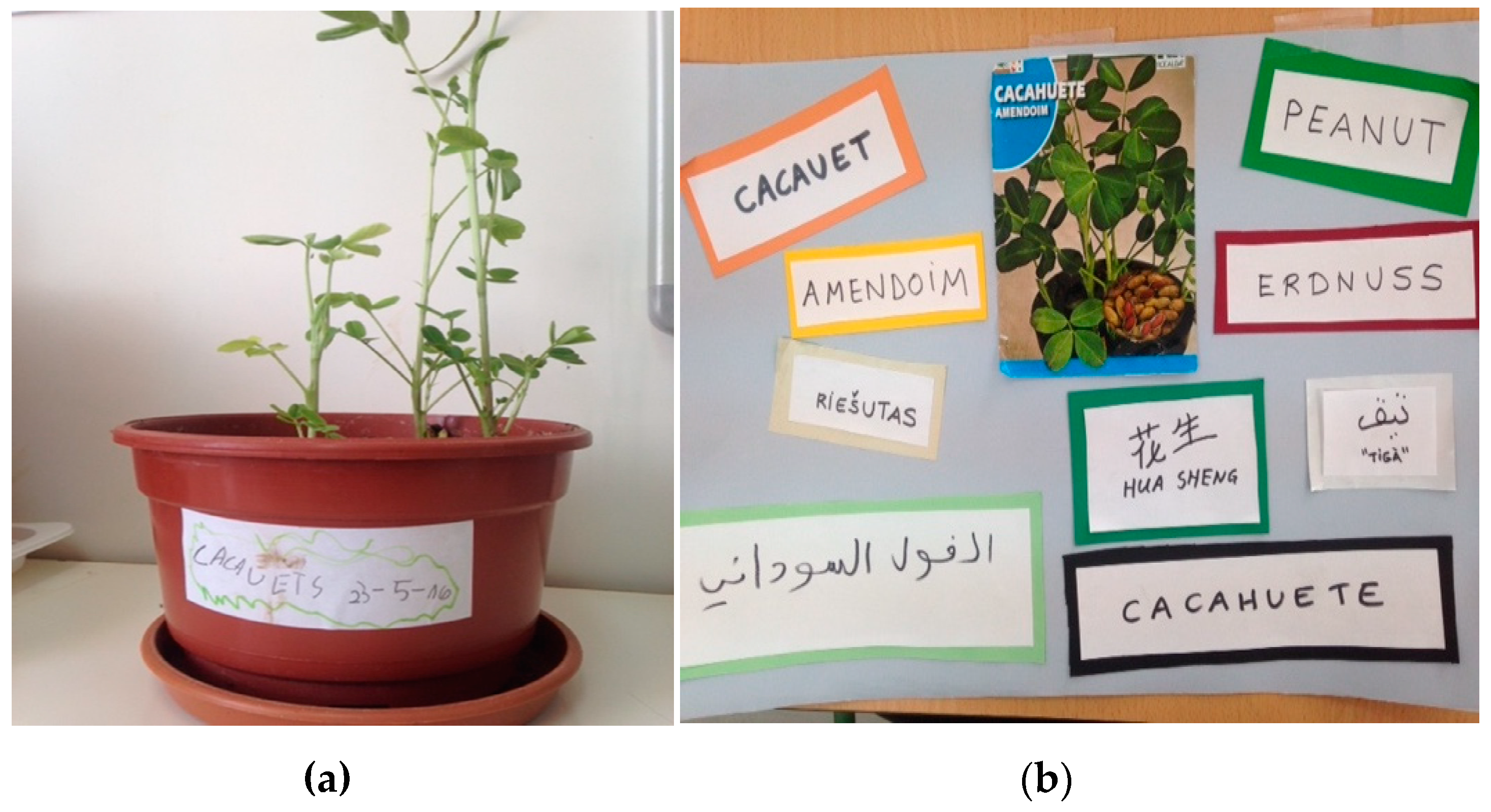

After the five visits were conducted by the teachers, a list of the funds of knowledge uncovered was collectively produced in the context of the study group. Teachers were in agreement that many of these funds of knowledge were the same in the different families visited, and were actually likely to be present in other families. They included, for example, plurilingual competences (various language were identified including Catalan, Spanish, English, French, Chinese and Sarahule, among other African languages), gardening knowledge, practices and skills (e.g., some had plots of land where they grew different products from their countries of origin), hobbies such sports, music (e.g., typical dances from African countries), or board games and skills relating to cooking. In particular, teachers were surprised at the importance of peanuts in the kitchens in two of the five homes they visited. The idea of using and mixing peanuts with other food (i.e., rice) came as a surprise to teachers, as well to other students when teachers explained this in class. For this reason, teachers decided to design and implement an educational activity focusing on peanuts for their students, who were aged 5 and 6.

The activity consisted of planting peanuts and observing the whole process of plant growth in order to connect this with the natural sciences. Moreover, the activity was connected with literacy and language acquisition using various languages present in the students’ families (see

Figure 2).

This educational activity enabled curricular areas in natural sciences and language to be linked with the knowledge and experience of some families linked to the uses of peanuts, as well as other family contexts even though they were not visited. For example, one student explained to the class group that they sold peanuts in their family store; indeed, they were one of their most successful products. This connection was so significant for the families that one of them even decided to cook a dish involving peanuts and bring it to the school party at the end of the semester.

3.2. Identities in Dialogue. Exploring Cultural Funds of Identity

The funds of identity that emerged in the development of the activities contributed to the creation of spaces for dialogue with educators based on their social realities. By way of example, in the theatrical expression workshop on cultural backgrounds, a dialogue was generated around cultural identities and, specifically, about those cultural manifestations that occurred in school-society and in the family. During this session all the participants were racialized—three students and two researchers/educators who shared experiences of transculturality—which generated a space of trust and dialogue to address the subject of identity without being judged or questioned. As a result of a theatrical dynamic that sought to make visible the malleable and liquid nature of identity, students shared personal reflections: on how people tried to pigeonhole them into one identity or another, on labels imposed on them such as the Muslim or the gypsy, on strategies of assimilation and/or resistance in relation to the use of languages and on the experience of dealing with the expectations and motivations of families. These types of issues, which usually emerge in the individuality of each person or in non-formal contexts, were able to be shared within the school and under the supervision of educational agents. More importantly, they were allowed to construct their own narratives about it, sharing their experiences and legitimizing them in the context of an institutional educational practice. In short, both the potentialities and the difficulties of a dialogue about cultures were shown, which is itself a dialogue between cultures.

Likewise, when working in small groups accompanied by an educator, apart from the aforementioned, there were other events that brought us closer to understanding and accompanying the students. In a first event, a student developed an unprecedented connection between the personal and family world and school practice, transitioning—through dialogue—from resistance to incorporating school practice into their own identity, to reflection on their personal trajectory. In a second event with another student, a dialogue without censorship occurred on the notion of culture from one’s experience of belonging. A third event evidenced the subtlety of processes of cultural assimilation and the actions of resistance to it, how emotions play a central role in processes of assimilation and how the dynamics of acceptance in relationships at school are fundamental in the generation of resistance actions.

All these events show, from the dialogue generated by funds of identity, the inadequacy of essentialist approaches to cultural diversity. Although in the dialogues of the students there are constant references to ‘payos’ and ‘moros’ (derogatory terms for non-Roma and Muslim North Africans, respectively) etc.—echoing popular language and laden with racist connotations—those elements that link students, through emotions, to a complex network formed by family, community, religion, friendships and the school itself, emerged as key elements of cultural identity.

4. Discussion

Recently, culturally sustaining pedagogy has been suggested to describe educational practices that seek to legitimate, perpetuate and foster linguistic, literate and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling and as a much-needed response to the current network-based, multicultural societies of the 21

st century [

17,

23]. By “multicultural societies”, we mean different nationalities, languages, religions, lifestyles or values living together in public spaces such as public schools. Thus, the intention was to go beyond highlighting the importance of cultural diversity, and address the need not only to recognize it, but also to maintain and develop it. Hence, there is talk of sustainability.

This pedagogical approach is, in fact, the result of several decades of research and intervention aimed at combating deficit thinking in education which flourishes in an atmosphere of supposed white superiority, engendered by systemic processes linked to exclusion, racism and xenophobia. Conversely, this new approach upholds the value and meaningful practices of students and communities of color, Latinas or other stigmatized and underrepresented groups in school culture and practice.

Pioneering research lines, such as funds of knowledge [

6,

7,

8] or, more recently, funds of identity [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], express a commitment linked to the nature and mission of public schools, committed to democracy and processes of social justice. This commitment entails the need to sustain students’ meaningful practices and their ways of being, experiencing and feeling, and their significant cultures. Here, it is important to clarify that by ‘culture’ we are not referring to homogeneous, perennial elements shared by a particular community recognized under a national, ethnic or cultural label, but rather to hybrid processes—concrete practices forged in the different scenarios and contexts of life and activity in which one participates [

24]. In this sense, in the case of activities and practices such as, for example, traditional sports and games, there are cultural, social and identity aspects that are often unknown, or simply disregarded, by school culture and practice [

25]. We believe this is something that, from a critical perspective, must be overcome, and efforts should be made towards educational models and practices that value, and indeed, guarantee, the survival of the different experiences, practices and life contexts of the learners, going beyond the typical assimilationist values and practices prevalent in schools, in which the curriculum, instruction and teaching practices are often disconnected from the meaningful experiences, life contexts and practices of the learners [

8].

The two examples described in this article allow us, on the one hand, to illustrate this intention and, on the other, to offer avenues of exploration for the development of more inclusive and culturally sustainable educational practices, by which we mean practices that not only recognize the languages, identities and meaningful reference points of the learners (as in the example of the funds of knowledge approach), but practices that also explain and safeguard diverse forms of cultural identity, even when the protagonists are unaware of them (as in the case described in the funds of identity intervention).

In this sense, we believe the main contribution of the project described here is to be found in its methodology, since it offers us a strategy for intervention that is sensitive to the resources of a family unit, as well as the learners’ own areas of sense (or ‘meaningful circles’); the project illustrates how to design an educational activity that recognizes and sustains the intellectual and meaningful practices of the learners and their families. In addition, although it is not our focus here, the study suggests there is a need to create environments and spaces for teacher training aimed at improving their intercultural pedagogical abilities. A recent study, carried out with primary and middle school teachers, pointed out how important it is to create training practices that help teachers to reflect on pedagogical practices and models designed to improve their intercultural teaching skills [

26].

From both the example of peanuts and that of cultural identity, it can be inferred that an inclusive educational practice must be aligned with pedagogies of cultural sustainability, legitimizing in the school the sources of meaning and diverse cultural expressions, as well as linking them to the curriculum and pedagogical objectives, and even developing their practice so that they can become known and adopted by other students, other families. To this end, we believe that a pedagogy of cultural and identity sustainability should normalize diversity (incorporating it into school practice), as well as diversify normality. For instance: Why not incorporate sign language for all students? Why not offer the learning of Arabic or Chinese in a context in which they are the mother tongues of students? Why not speak of a Peninsular [Iberian Peninsula] history incorporating the history of the Roma people? Why not also talk about people from the Global South who have marked historical milestones in humanity? Or why not revitalize the knowledge of Latin American countries, and cease proclaiming a false discovery of America?

The aim is to cultivate the development of practices and languages, to recover meaningful models at risk of disappearing, for example through the recovery of traditional stories and games shared in the family culture; to mark a curricular agenda that moves away from the “whiteness” [

23] that maintains an educational practice which restrains diversity and does not allow the attainment of social equity in terms of legitimacy. It is in this sense that education for cultural sustainability involves going beyond mere tolerance or recognition of the cultural fact. It also entails, from the perspective of funds of identity, incorporating the voices of learners through artifacts created by them that allow the objectives, subjects and curricular content to be contextualized and personalized [

27,

28,

29]. This, in addition, could facilitate processes of transcultural or hybrid construction that broaden the repertoires of significance and meaning, often reduced in school practice and activity [

30,

31]. By hybrid and transcultural identities, we mean forms of construction and expression that do not lead to ethnic flight or withdrawal (rejecting the host society) or to simple cultural assimilation (rejecting the culture of origin and its society and legacy), and instead help to integrate, manage and allow creative movement between the acceptance of family cultural practices and referents, and other codes, values and practices of the host society. This translates into greater multicultural competence, which we all need in today’s diverse contexts [

30,

31].

Nevertheless, one limitation of the study described here is that it does not analyze the impact of the two educational projects (funds of knowledge and funds of identity) on the possible construction of transnational identities in students, or their learning and academic performance; the impact on the families visited, or on the teachers themselves based on their experience and participation in the project. On the other hand, since we are dealing with two specific contexts of intervention, it would not be possible to generalize the results. In addition, in terms of the two approaches described here, there is another limitation of the study that suggests a future line of research-intervention involving the documentation of both funds of knowledge and funds of identity in order to incorporate these into school-educational practice. Within the available literature, there is, in fact, an educational activity based on the convergence of funds of knowledge and identity, on two levels of analysis—families and learner [

9]. However, this activity has not been implemented, only designed. The reason for this is that it was the final project of a Master’s degree by a trainee teacher whose main aim was to design, for the first time, an educational activity based on the synergies between funds of knowledge identified and funds of identity elicited. Therefore, it was not a fully authentic context—the teacher was carrying out his training in the education center, but was not a member of the teaching staff—and hence the educational activity designed could not actually be implemented.

Thus, future research is needed to precisely account for the relationship we predict here, between cultural sustaining pedagogies and promotion of the construction of transcultural identities, and future participatory research-action projects are needed to allow both approaches to converge, as we believe this may enrich both the perspective of funds of knowledge and that of funds of identity. That is to say, it would be profitable, in future research, to incorporate both sets of funds in the design of educational activities: the family funds of knowledge together with the learners’ funds of identity, which was not the case in the two interventions described here. On the other hand, we also need an in-depth analysis of the impact of the educational interventions such as these on both students and teachers. We need to know if students improve in terms of school performance. We also need to know more about what teachers think with regard to the funds of knowledge and the funds of identity approaches—the strengths and weaknesses, and the areas for improvement.