Prospects of Public Participation in the Planning and Management of Urban Green Spaces in Lahore: A Discourse Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Discourse Analysis

1.2. Case Study

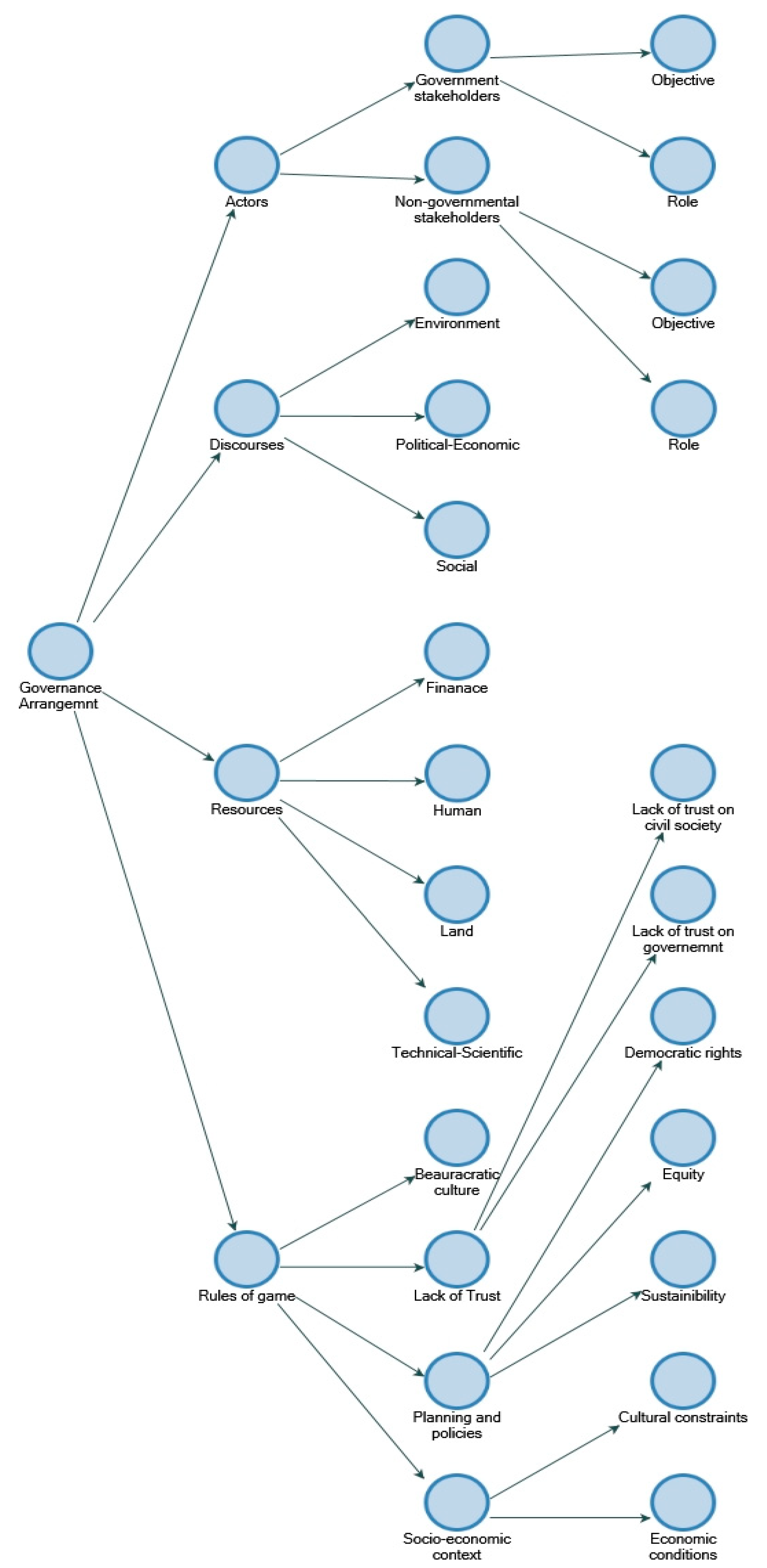

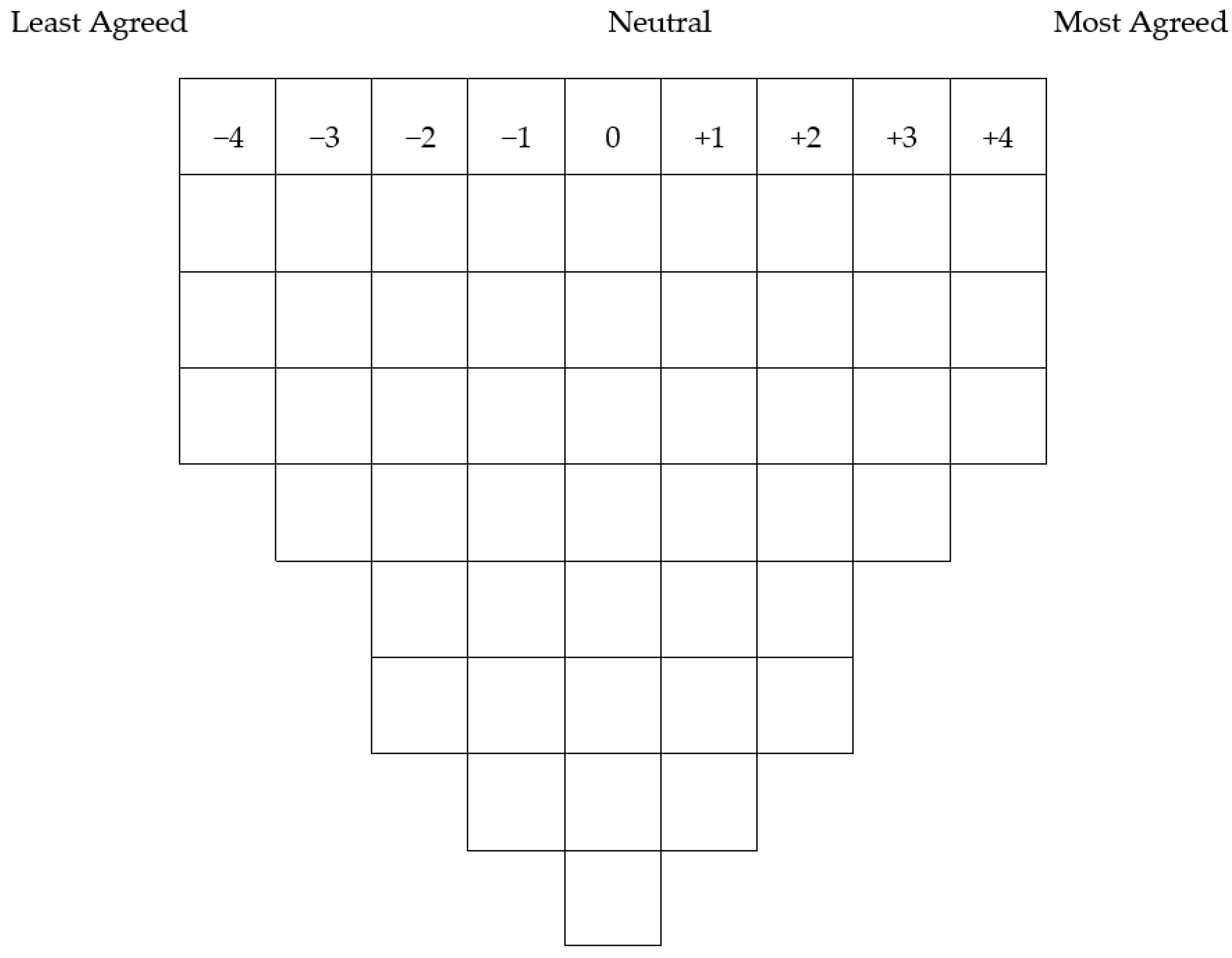

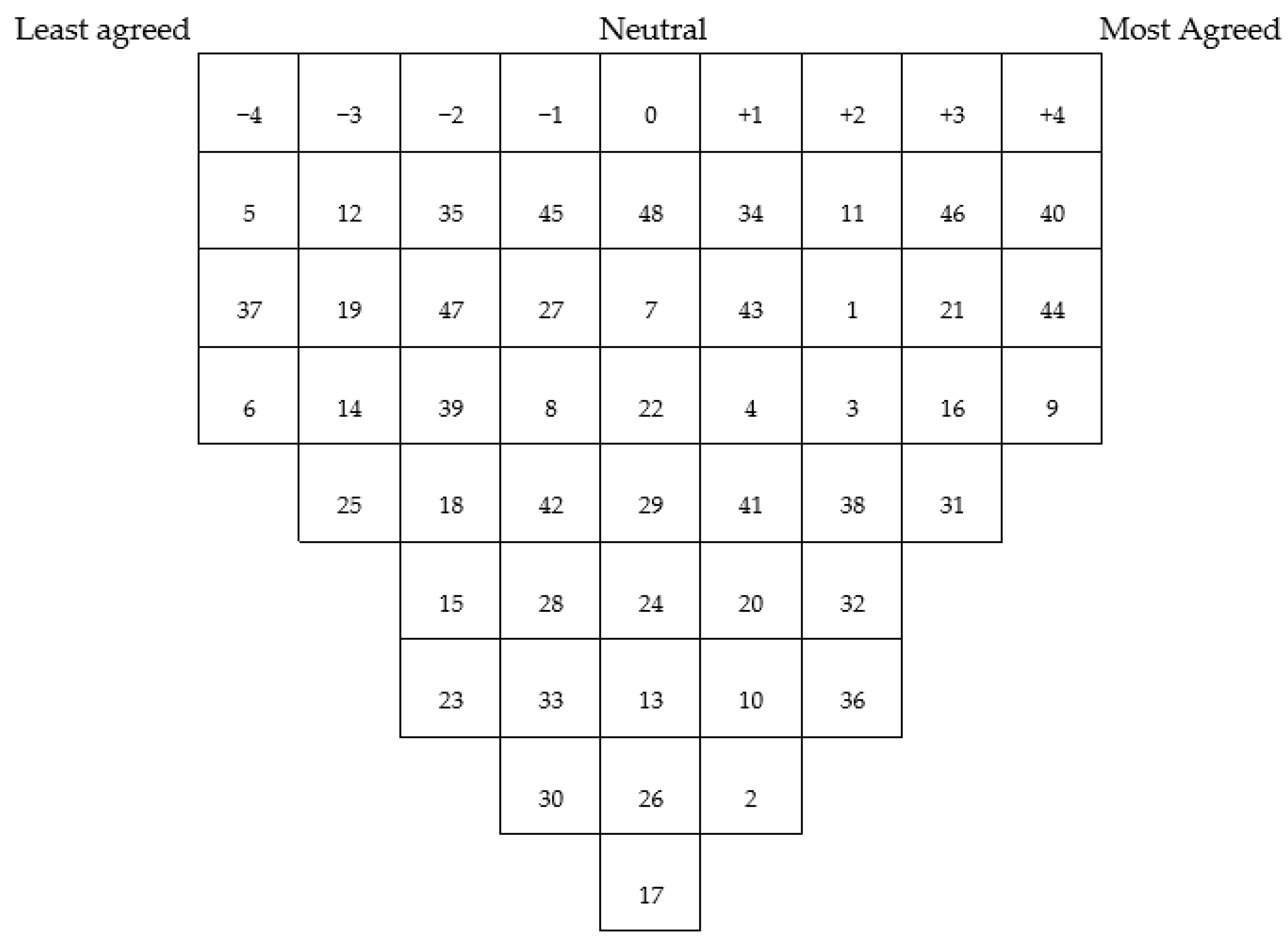

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Discourse A: Efficient Management

3.2. Discourse B: Pro/Anti-Administrative

3.3. Discourse C: Leadership and Capacity Building

3.4. Discourse D: Decentralisation or Elite Capture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- How do you understand urban green spaces? Any example.

- Can you identify some specific issues regarding the quality (facilities and maintenance) and quantity (amount and accessibility) of existing green spaces?

- Can you identify different actors in the planning and management of urban green spaces in Lahore? What role they play, or in what ways they are important?

- What sort of relationship exists among these actors for the governance of green spaces?

- Why are urban green spaces important?

- What are the main objectives of the planning and management of the green spaces in Lahore? Probe for benefits such as economic, aesthetic, recreational, city image, etc.

- Do you agree with objectives mentioned above, or what do you think it should be? (difference and similarities)

- What factors do you think can hinder the achievement of your goals?

- How are green spaces planned and managed in Lahore?

- Does the development of a green space associate with some other types of developments in Lahore?

- What is the role of your organization? How do you participate in this process?

- Does government facilitate the participation of other actors, and to what extent?

- How are the resources for the green spaces in Lahore ensured or obtained? Probe further for financial, political and human resources

- Does the procurement of resources disturb the balance of power by giving some groups extra leverage during developing and managing green spaces in Lahore?

- How can the green spaces in Lahore be related to the sustainable development? (economic, social and environmental development)

- What are the challenges to achieving this goal?

- Which is the most critical factor? Why?

- Which institutions/organizations should be improved for the development and management of green spaces?

- What constitutes a way forward for the successful governance and management of green spaces?

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Q-Sort.No. | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C | Factor D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2454 | −0.1446 | 0.1368 | 0.524 |

| 2 | 0.5054 | −0.1363 | −0.1765 | 0.3383 |

| 3 | 0.2745 | −0.3719 | −0.0829 | 0.1099 |

| 4 | 0.0416 | 0.4762 | −0.2296 | −0.1201 |

| 5 | 0.574 | 0.1606 | −0.2095 | 0.1252 |

| 6 | 0.2669 | −0.3091 | −0.1563 | 0.0395 |

| 7 | −0.1165 | 0.0975 | 0.3797 | −0.2352 |

| 8 | 0.3286 | 0.0498 | 0.1579 | 0.1248 |

| 9 | 0.595 | 0.2068 | 0.0924 | 0.0774 |

| 10 | 0.6446 | 0.0753 | 0.1742 | 0.0515 |

| 11 | 0.1509 | 0.2066 | 0.0678 | −0.4369 |

| 12 | 0.2587 | 0.2465 | 0.0547 | 0.1772 |

| 13 | 0.451 | 0.0007 | 0.2453 | 0.1068 |

| 14 | −0.0344 | 0.1534 | 0.2126 | 0.1961 |

| 15 | 0.1441 | 0.2244 | −0.2044 | −0.2174 |

| 16 | 0.2593 | 0.1549 | −0.0566 | −0.2877 |

| 17 | 0.4023 | 0.1071 | 0.3679 | −0.2675 |

| 18 | −0.1815 | 0.2363 | −0.1531 | 0.1663 |

| 19 | −0.2286 | 0.3502 | 0.0747 | 0.1869 |

| 20 | 0.4308 | −0.1621 | −0.0631 | −0.2252 |

| 21 | 0.3866 | −0.1021 | 0.3451 | −0.2757 |

| 22 | 0.1193 | 0.277 | −0.01 | 0.1848 |

| 23 | 0.0553 | −0.5728 | 0.11 | −0.0661 |

| 24 | 0.4565 | 0.0712 | −0.4724 | 0.0538 |

| 25 | 0.548 | 0.1374 | −0.1736 | 0.1254 |

| 26 | 0.0164 | −0.2158 | 0.4136 | −0.1404 |

| 27 | 0.2733 | 0.4381 | 0.1723 | 0.2788 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.2499 | 1.6816 | 1.2975 | 1.3298 |

| % of Explanatory Variance | 12 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

Appendix E

| Q-Sort.No. | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C | Factor D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.3991 X | 0.0595 | −0.0871 | −0.4516 X |

| 2 | 0.4912 X | 0.2707 | −0.2968 | −0.1303 |

| 5 | 0.5415 X | 0.1109 | −0.2621 | 0.2015 |

| 8 | 0.3768 X | 0.0318 | 0.0824 | −0.0338 |

| 9 | 0.6169 X | 0.0353 | 0.0270 | 0.1699 |

| 10 | 0.6327 X | 0.1587 | 0.1216 | 0.1180 |

| 13 | 0.4812 X | 0.1125 | 0.1713 | −0.0358 |

| 25 | 0.5205 X | 0.1128 | −0.2276 | 0.1721 |

| 27 | 0.5205 X | 0.1128 | −0.2276 | 0.1721 |

| 3 | 0.1637 | 0.4165 X | −0.0948 | −0.1527 |

| 6 | 0.1319 | 0.3929 X | −0.1367 | −0.0477 |

| 19 | −0.0203 | −0.4563 X | −0.0356 | −0.0743 |

| 20 | 0.2325 | 0.3895 X | 0.0446 | 0.2426 |

| 23 | −0.1040 | 0.5048 X | 0.1722 | −0.2287 |

| 7 | −0.840 | −0.1416 | 0.4356 X | 0.0754 |

| 17 | 0.3524 | 0.0780 | 0.4310 X | 0.2533 |

| 21 | 0.2763 | 0.2552 | 0.4307 X | 0.1673 |

| 24 | 0.3349 | 0.2070 | −0.4615 X | 0.2677 |

| 26 | −0.0086 | 0.1476 | 0.4499 X | −0.1154 |

| 4 | 0.0677 | −0.3099 | −0.1961 | 0.3956 X |

| 11 | 0.0350 | −0.0088 | 0.2257 | 0.4568 X |

| 15 | 0.0592 | −0.0327 | −0.1138 | 0.3776 X |

| 16 | 0.1451 | 0.0646 | 0.0534 | 0.3862 X |

| 12 | 0.3660 | −0.1582 | −0.0477 | 0.0281 |

| 14 | 0.1283 | −0.2373 | 0.0984 | −0.1610 |

| 18 | −0.0647 | −0.2910 | −0.2246 | −0.0245 |

| 22 | 0.2429 | −0.2320 | −0.1101 | 0.0178 |

Appendix F

| Statements | Factor ‘A’ | Factor ‘B’ | Factor ‘C’ | Factor ‘D’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | People do not realize what is quality of life? Quality of life is not about taking the big house; quality of life is what is inhaling, how you feel, or is your brain at peace. That is quality of life. | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| 2 | At least all the parks in Lahore should be digitized and mapped in GIS and as online information, where people can know when its maintenance is due, and when it is done. How much is the budget, how much has been spent? There should be information sharing, so that people will come to know the government preferences towards the parks and the green spaces. | 2 | 0 | −2 | 3 |

| 3 | I feel that these local group environment groups should come forward. They should take the lead and the NGO should back them up by giving excellent solid scientific support. | 1 | −2 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | NGOs have a very limited scope. They can do some pilot projects which can address four or five schools, but if you want a big scale, then you need to involve the government. | −2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | I think there is no community culture here. They need to develop a community culture. Where there are parks, people in the neighborhood should have meetings, or they should have clubs, so they can specify that in this area what do they need. | 2 | 0 | −4 | −4 |

| 6 | Parks and Horticulture is authority, why do we have authorities? WAPDA is another authority, and so is LDA, so why authorities? Why are not these services? If these are services, you can involve people. | −2 | −3 | −2 | −2 |

| 7 | Every citizen has to contribute to green spaces, because they are using these resources or nature. They are consuming, so they must play their part. | 4 | 4 | −2 | −3 |

| 8 | When we write PHA at an institutional level they bluntly refused us and said we do not have plants. And when we ask them by using personal contacts they told us do not worry, you will get all the plants. | −2 | −1 | −1 | 1 |

| 9 | The government does not allocate enough budgets for EPD. That shows the priority of our leaders, our politicians and our government, and if they think that the environment is OK this is a western agenda, and these are rich people tantrums. | −1 | −4 | −1 | 4 |

| 10 | The cantonment belongs to the military, so it is the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence. So, the chief executive of the cantonment is not answerable to the chief minister of Punjab. So, it becomes a very difficult proposition. | −2 | −2 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | In our country our bureaucratic system there are turf wars. There is less coordination, unity, and not a single united policy on which everyone is agreed. | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | If the state is a signatory of Biodiversity (CBD) they need to conserve flora and fauna both. They need to conserve it as an obligation. | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 13 | The civil society should take responsibility. Sometimes there is limited capacity and knowledge, so civil society can bridge that gap and ensure that good laws are enacted and complied with. | 1 | 2 | 4 | −3 |

| 14 | The local government needs to generate funds. So, if we go to any park or historical place in the western country, we have to pay for that. Why cannot we pay the fee? They can generate their own resources. | 0 | 3 | 1 | −4 |

| 15 | EPD cannot do enforcement efficiently. The most important reason is if someone plants trees, where is the land? | −3 | −1 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | We have brought back the local government system again after a nine year gap, but they do not have any power. All of the authority is held by the chairman of the LDA or the chairman of the PHA. | −1 | 2 | −1 | 3 |

| 17 | In our country not much importance is given to the environment. Once climate change was a ministry, and then it becomes a department, which again became a ministry, but a toothless kind of ministry. | 3 | −2 | −3 | 0 |

| 18 | Nothing can be seen in the parks that involves the user to take the ownership of the parks. So this concept of ownership is not here, in which people think this is my park, and there should be flowers and the trees of my choice. | 0 | 1 | −2 | 0 |

| 19 | Civil society sometimes cannot get that support which is needed from media, judiciary, and local people. | −2 | −1 | 1 | −3 |

| 20 | Green spaces are not adequate in the inner city. We do have funds, but people don’t want to leave their places. they are ready to die for every single inch of land | −4 | 0 | −1 | 2 |

| 21 | If local government needs a budget they cannot increase a few fines or fees or tax, as they need to take permission from the provincial government, and the provincial government will not allow it. They cannot generate their own funds. So, the cities cannot be run. | 0 | 1 | −2 | 2 |

| 22 | For a long time new parks have not been formed, as the government does not have sufficient land. | −4 | 4 | 0 | −2 |

| 23 | This is cuckoo land. These people in the inner city do not have any money to maintain their houses, so how do you ask these people to make a garden on their rooves. | −4 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 24 | I believe that academia can be used to sensitize and to communicate the importance of the environment and urban green spaces to the people. | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | There should be a department who plays the leading role in coordinating, and it is the Planning and Development Department, because recently all the planning and development is being done under it. | −2 | −2 | 0 | −1 |

| 26 | How many people have the budgeting concept? Even if I have it, I will not want that headache. In this situation, it is unnecessary interference to involve a layman. | −3 | −4 | 3 | −1 |

| 27 | NGOs have not done any significant project on urban green spa spaces. What they did is in bits and pieces, like lobbying, advocacy, with journalists, students and the private sector | −1 | 1 | −1 | −3 |

| 28 | The latest trend is that private housing societies import plants from China or Thailand that are fully grown plants. So that is how they are getting good business, but that is neither our economy, not the indigenous plant. | −1 | −2 | −2 | 1 |

| 29 | I think things are getting commercialized. People go to green spaces for a walk, but they have increased the grey structure. You are bringing that kind of facilities which are damaging the true spirit of UGS. | 1 | 4 | −4 | 3 |

| 30 | The environment is not our priority. Our policymakers want to show that stuff to the masses, on the basis of which, they will get more votes in the coming elections. | 3 | 0 | 2 | −2 |

| 31 | Planning varies from area to area in Lahore. Posh areas where policymakers live and have their influence are better looked after and managed. | 0 | −3 | 2 | 4 |

| 32 | The goal of the PHA is a politically infused goal based upon a CM vision, and that is; Lahore should be green. They want to make it a beautiful and a model city. | −3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 33 | I must say that the role of Ulemas can be very positive. They are being used for the wrong things. If we engage them, I mean to say that we can use that institution as well. | 3 | −1 | 2 | −1 |

| 34 | The local government is a significant stakeholder, as it has the authority to identify the areas for the provision of green spaces. | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 35 | I think technocrats should have a bigger role; the right man for the right job is what needed. But it is not being done. | 4 | −2 | 1 | −1 |

| 36 | Green spaces are meant to be used by users, but if you ask me, if they have any role in policy making and decision making, it is not like that they should be involved in this process. | 2 | 2 | −3 | 0 |

| 37 | I have seen that our private sector is more aware than the government sector on the virtue of environment protection, as most of the private housing schemes have green spaces as their dominant features. | −1 | 0 | −4 | −4 |

| 38 | I think in our system the NGOs need to interfere, because when they protest on something, it catches the attention of the media, resulting in some progress, negotiation, and so there is some betterment. | 0 | −3 | 4 | 1 |

| 39 | If you talk to the forest department they talk about forestry, but they do not have any clarity and comprehension on urban forestry, as it should be. | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 |

| 40 | The primary use of UGS is none other than having a walk or jogging, or holding social gatherings with friends in the park, where our children can play. | 0 | 0 | −1 | 2 |

| 41 | Media covers the issues, but not that much, because it is not in the advertisers’ interest, nor is it of the corporate interest, so they do not focus on them. | 2 | −3 | −3 | 2 |

| 42 | UGS are controlled by the bureaucracy. So, if one bureaucrat comes for six months and is replaced by another, they have little chance to understand the problem comprehensively | 0 | −1 | −3 | −2 |

| 43 | The green spaces and its problem cannot be solved until it is not taken at the government level. Other problems can be solved at the individual level, but for green spaces and tree plantation, government has to give some policy. Yet at city level, government has to give some policy. | −1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 44 | EPD should be effective because it is the environment that it is supposed to deal with exclusively, but at present, the EPD hardly makes its presence felt. | 1 | 0 | 3 | −1 |

| 45 | Students are doing research, but they do not have any facilities. Even if you ask data from the PHA, they will not share data with researchers. | −1 | −4 | −1 | −2 |

| 46 | When talking about the Lahore city, the local environmental group is a powerful pressure group, so its activists do not let anything go wrong here easily. They are quite vigilant; parks cannot be transformed for any other purposes. | −3 | −1 | 2 | −1 |

| 47 | We do not have coordination among departments. So, if our mayor and his institutions are cooperating with the PHA, the PHA is not coordinating with the forest department. It wastes the resources in overlapping, and thus we cannot benefit from each other’s expertise. | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 48 | Private participation is too little. And if we talk about what the private sector is doing, it is mostly undertaking tree planting initiatives. They have no participation in policymaking. | 2 | 1 | 1 | −2 |

References

- Mea, A. Millennium Ecosystem. In Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S. Our Common Future; Brundtland Commission: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, R.A.; Lefkowitz, D.S.; Skole, D.L. Changes in the Landscape of Latin America between 1850 and 1985 I. Progressive Loss of Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 1991, 38, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human-Environment interactions in Urban Green Spaces—A Systematic Review of Contemporary Issues and Prospects For Future Research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Wiesen, A. Restorative Commons: Creating Health and Well-Being through Urban Landscapes; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 39.

- Chiesura, A. The Role of Urban Parks for the Sustainable City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnendijk, C.C.; Annerstedt, M.; Nielsen, A.B.; Maruthaveeran, S. Benefits of Urban Parks: A Systematic Review; IPFRA: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ernstson, H.; Van Der Leeuw, S.E.; Redman, C.L.; Meffert, D.J.; Davis, G.; Alfsen, C.; Elmqvist, T. Urban Transitions: On Urban Resilience and Human-Dominated Ecosystems. Ambio 2010, 39, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattijssen, T.; Buijs, A.; Elands, B.; Arts, B. The ‘Green’and ‘Self’in Green Self-Governance—A Study of 264 Green Space initiatives by Citizens. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2018, 20, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonchuen, P. Globalisation and Urban Design: Transformations of Civic Space in Bangkok. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2002, 24, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R. Collective Action and the Urban Commons. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2011, 87, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S.; Bendt, P.; Snep, R.; Van Der Knaap, W.; Ernstson, H. Urban Green Commons: Insights on Urban Common Property Systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van Den Berg, A.; Van Dijk, T.; Weitkamp, G. Quality Over Quantity: Contribution of Urban Green Space To Neighborhood Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herzele, A.; Wiedemann, T. A Monitoring Tool For the Provision of Accessible and Attractive Urban Green Spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffimann, E.; Barros, H.; Ribeiro, A. Socioeconomic inequalities in Green Space Quality and Accessibility—Evidence from A Southern European City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, A.Y.; Jim, C.Y. Willingness of Residents To Pay and Motives For Conservation of Urban Green Spaces in the Compact City of Hong Kong. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S. Post-Socialist Urban Forms: Notes From Sofia. Urban Geogr. 2006, 27, 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendel, H.E.W.; Downs, J.A.; Mihelcic, J.R. Assessing Equitable Access To Urban Green Space: The Role of Engineered Water infrastructure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6728–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colding, J.; Lundberg, J.; Folke, C. incorporating Green-Area User Groups in Urban Ecosystem Management. Ambio 2006, 35, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A. Common Property institutions and Sustainable Governance of Resources. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Sustainable Governance of Common-Pool Resources: Context, Methods, and Politics. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2003, 32, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The Struggle To Govern the Commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, C.; Maye, D.; Pearson, D. Developing “Community” in Community Gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Fondo De Cultura Económica: Mexico City, México, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Janssen, M.A.; Eries, J.M. Going Beyond Panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15176–15178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Gunderson, L.H. Pathology and Failure in the Design and Implementation of Adaptive Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, F. Alternatives to Conventional Management: Lessons From Small-Scale Fisheries. Environments 2003, 31, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S.; Meffe, G.K. Command and Control and the Pathology of Natural Resource Management. Conserv. Biol. 1996, 10, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hughes, T.P. Navigating the Transition To Ecosystem-Based Management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9489–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, P.; Gunderson, L.; Carpenter, S.; Ryan, P.; Lebel, L.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S. Shooting the Rapids: Navigating Transitions To Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric Systems as One Approach for Solving Collective-Action Problems; School of Public & Environmental Affairs Research Paper; Indiana University: Bloomington, Indiana, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. Transitions towards Adaptive Management of Water Facing Climate and Global Change. Water Resour. Manag. 2007, 21, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Becker, G.; Knieper, C.; Sendzimir, J. How Multilevel Societal Learning Processes Facilitate Transformative Change: A Comparative Case Study Analysis on Flood Management. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Crona, B.; Armitage, D.; Olsson, P.; Tengö, M.; Yudina, O. Adaptive Comanagement: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Evolution of Co-Management: Role of Knowledge Generation, Bridging Organizations and Social Learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, L.; Berkes, F. Co-Management: Concepts and Methodological Implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 75, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcginnis, M.; Ostrom, E. Social-Ecological System Framework: Initial Changes and Continuing Challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natcher, D.C.; Davis, S.; Hickey, C.G. Co-Management: Managing Relationships, Not Resources. Hum. Organ. 2005, 64, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, K.; Gruby, R.L. Polycentric Systems of Governance: A theoretical Model For the Commons. Policy Stud. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, L.; Anderies, J.M.; Campbell, B.; Folke, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Wilson, J. Governance and the Capacity To Manage Resilience in Regional Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, G.; Pittman, J.; Alexander, S.M.; Berdej, S.; Dyck, T.; Kreitmair, U.; Rathwell, K.J.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Vogt, J.; Armitage, D. Institutional Fit and the Sustainability of Social–Ecological Systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. An international Comparison of Four Polycentric Approaches to Climate and Energy Governance. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3832–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, T. Factors Affecting Forest User’s Participation in Participatory Forest Management; Alamata Community Forest: Tigray, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Avritzer, L. Participatory Institutions in Democratic Brazil; Woodrow Wilson Center Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, W. How Culture Shapes Environmental Public Participation: Case Studies of China, The Netherlands, and Italy. J. Chin. Gov. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstson, H.; Barthel, S.; Andersson, E.; Borgström, S. Scale-Crossing Brokers and Network Governance of Urban Ecosystem Services: The Case of Stockholm. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chado, J.; Johar, F.B. Public Participation Efficiency in Traditional Cities of Developing Countries: A Perspective of Urban Development in Bida, Nigeria. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 219, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denhardt, J.; Terry, L.; Delacruz, E.R.; Andonoska, L. Barriers to Citizen Engagement in Developing Countries. Int. J. Public Adm. 2009, 32, 1268–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Campbell, B.; Wollenberg, E.; Edmunds, D. Devolution and Community-Based Natural Resource Management: Creating Space for Local People to Participate and Benefit. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 2002, 76, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Apthorpe, R.; Gasper, D. Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse. In Arguing Development Policy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, J.; Proops, J. Seeking Sustainability Discourses with Q Methodology. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 28, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B.; Hardy, C. Discourse and institutions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge; Penguin UK: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. The Adolescence of institutional theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1987, 32, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Urban Greening To Cool Towns and Cities: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Miettinen, A. Property Prices and Urban Forest Amenities. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2000, 39, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Z.; Baig, M. Pollution of Lahore Canal Water in the City Premises. In Environmental Pollution; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mahboob, M.A.; Atif, I. Assessment of Urban Sprawl of Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan Using Multi-Stage Remote Sensing Data. Methodology 1990, 1, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, K.; Rana, A.D.; Tariq, S.; Kanwal, S.; Ali, R.; Haidar, A. Groundwater Levels Susceptibility To Degradation in Lahore Metropolitan. Depression 2011, 150, 801. [Google Scholar]

- Qutub, S.A. Rapid Population Growth and Urban Problems in Pakistan. Ambio 1992, 21, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, I.A.; Bhatti, S.S. Lahore, Pakistan–Urbanization Challenges and Opportunities. Cities 2018, 72, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, S. Temporal Analysis of Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Lahore-Pakistan. Pak. Vis. 2012, 13, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi, S.A.; Kazmi, J.H. Analysis of Socio-Environmental Impacts of the Loss of Urban Trees and Vegetation in Lahore, Pakistan: A Review of Public Perception. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ali, Z.; Noor, N.; Sidra, S.; Nasir, Z.; Colbeck, I. Measurement of No 2 indoor and Outdoor Concentrations in Selected Public Schools of Lahore Using Passive Sampler. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2015, 25, 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi, A.; Masuda, H.; Firdous, N. Toxic Fluoride and Arsenic Contaminated Groundwater in the Lahore and Kasur Districts, Punjab, Pakistan and Possible Contaminant Sources. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 145, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, S.; Shirazi, S.A.; Ahmed Khan, M.; Raza, A. Urbanization Effects on Temperature Trends of Lahore During 1950–2007. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2009, 1, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R. A Primer on Q Methodology. Operant Subj. 1993, 16, 91–138. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.R. Q Methodology and Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckeown, B.; Thomas, D.B. Q Methodology; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, W. The Study of Behavior: Q-Technique and Its Methodology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzi, S.; Carter, N.T.; Lovett, J.C. Exploring Discourses on international Environmental Regime Effectiveness With Q Methodology: A Case Study of the Mediterranean Action Plan. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.; Thompson, C.; Mannion, R. Q Methodology in Health Economics. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2006, 11, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, I. Q Methodology as Process and Context in interpretivism, Communication, and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy Research. Psychol. Rec. 1999, 49, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.J.; Tallontire, A.M.; Stringer, L.C.; Marchant, R.A. Which “Fairness”, for Whom, and Why? An Empirical Analysis of Plural Notions of Fairness in Fairtrade Carbon Projects, Using Q Methodology. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 56, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, S.; Donaldson, A.; Walker, G. Structuring Subjectivities? Using Q Methodology in Human Geography. Area 2005, 37, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.; Cook, B.; Bracken, L.; Cinderby, S.; Donaldson, A. Combining Participatory Mapping with Q-Methodology to Map Stakeholder Perceptions of Complex Environmental Problems. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 56, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P.; Vira, B. Q Methodology for Mapping Stakeholder Perceptions in Participatory Forest Management; Institute of Economic Growth Deli: Delhi, Indian, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J.S. Perspectives of Effective and Sustainable Community-Based Natural Resource Management: An Application of Q Methodology To Forest Projects. Conserv. Soc. 2011, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webler, T.; Danielson, S.; Tuler, S. Using Q Method to Reveal Social Perspectives in Environmental Research; Social and Environmental Research Institute: Greenfield, MA, USA, 2009; Volume 54. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, S.; Stenner, P. Doing Q Methodological Research: Theory, Method & Interpretation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Goverde, H. The Governance Capacity of (New) Policy Arrangements: A Reflexive Approach. In Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, B.; Buizer, M. Forests, Discourses, institutions: A Discursive-institutional Analysis of Global Forest Governance. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and Why? A Typology of Stakeholder Analysis Methods for Natural Resource Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, M.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Stakeholder Categorisation in Participatory integrated Assessment Processes. Integr. Assess. 2002, 3, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L.; Strutzel, E. The Discovery of Grounded theory; Strategies For Qualitative Research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Berejikian, J. Reconstructive Democratic theory. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1993, 87, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addams, H.; Proops, J.L. Social Discourse and Environmental Policy: An Application of Q Methodology; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Najam, A. The Four C’s of Government-Third Sector Relations’. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2000, 10, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, M. The Politics of Government-Ngo Relations in Africa. World Dev. 1989, 17, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszbein, A.; Lowden, P. Working Together for a Change: Government, Business, and Civic Partnershipsfor Poverty Reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.R.; Plummer, R.; Berkes, F.; Arthur, R.I.; Charles, A.T.; Davidson-Hunt, I.J.; Diduck, A.P.; Doubleday, N.C.; Johnson, D.S.; Marschke, M. Adaptive Co-Management For Social–Ecological Complexity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J. Creating incentives For increased Public Engagement in Ecosystem Management Through Urban Commons. In Adapting Institutions: Governance, Complexity and Social-Ecological Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, M.A.; Leahy, J.E.; Anderson, D.H.; Jakes, P.J. Building Trust in Natural Resource Management Within Local Communities: A Case Study of the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie. Environ. Manag. 2007, 39, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachapelle, P.R.; Mccool, S.F.; Patterson, M.E. Barriers To Effective Natural Resource Planning in A Messy World. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Ghatak, M. Property Rights and Economic Development. In Handbook of Development Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 5, pp. 4525–4595. [Google Scholar]

- Schlager, E.; Ostrom, E. Property-Rights Regimes and Natural Resources: A Conceptual Analysis. Land Econ. 1992, 68, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Hess, C. Private and Common Property Rights. Prop. Law Econ. 2010, 5, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Jagt, A.P.; Szaraz, L.R.; Delshammar, T.; Cvejić, R.; Santos, A.; Goodness, J.; Buijs, A. Cultivating Nature-Based Solutions: The Governance of Communal Urban Gardens in the European Union. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buijs, A.; Hansen, R.; Van Der Jagt, S.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Elands, B.; Rall, E.L.; Mattijssen, T.; Pauleit, S.; Runhaar, H.; Olafsson, A.S. Mosaic Governance For Urban Green infrastructure: Upscaling Active Citizenship From A Local Government Perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, H.; Ho, P.; Hafni, E.; Zarafshani, K.; Witlox, F. Multi-Stakeholder involvement and Urban Green Space Performance. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 785–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teal, M.; Huang, C.-S.; Rodiek, J. Open Space Planning For Travis Country, Austin, Texas: A Collaborative Design. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1998, 42, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, C.A. Destruction of Urban Green Spaces: A Problem Beyond Urbanization in Kumasi City (Ghana). Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpala, D. Regional Overview of the Status of Urban Planning and Planning Practice in Anglophone (Sub-Saharan) African Countries. In Global Report on Human Settlements (GRHS) 2009: Planning Sustainable Cities; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah, B. Assessment of Public–Private–Ngo Partnerships: Water and Sanitation Services in Slums. In Natural Resources Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- Atack, I. Four Criteria of Development Ngo Legitimacy. World Dev. 1999, 27, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, S. Ngo Legitimacy: Technical Issue Or Social Construct? Crit. Anthropol. 2003, 23, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, A.G.; Iqbal, M.A.; Mumtaz, S. Non-Profit Sector in Pakistan: Government Policy and Future Issues [With Comments]. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2002, 41, 879–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A.O. Government Failures in Development. J. Econ. Perspect. 1990, 4, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidball, K.G.; Krasny, M.E. Toward An Ecology of Environmental Education and Learning. Ecosphere 2011, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, S.; Nessa, A.; Aktar, M.; Hossain, M.; Saifullah, A. Perception of Environmental Education and Awareness Among Mass People: A Case Study of Tangail District. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 2012, 5, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J. Democratic Decentralization of Natural Resources: Institutionalizing Popular Participation; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and Disenchantment: The Role of Community in Natural Resource Conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Rethinking Community-Based Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.O. Environmental Education and Public Awareness. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2014, 4, 333. [Google Scholar]

- Ulleberg, I. The Role and Impact of Ngos in Capacity Development. In From Replacing the State to Reinvigorating Education; International Institute For Educational Planning Unesco: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mondiale, B. World Development Report 1997: The State in A Changing World; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D. Adaptive Capacity and Community-Based Natural Resource Management. Environ. Manag. 2005, 35, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondinelli, D.A.; Mccullough, J.S.; Johnson, R.W. Analysing Decentralization Policies in Developing Countries: A Political-Economy Framework. Dev. Chang. 1989, 20, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyono, P.R. One Step Forward, Two Steps Back? Paradoxes of Natural Resources Management Decentralisation in Cameroon. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2004, 42, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, M.S. Decentralisation: What Does It Contribute To? Added Value of Decentralisation For Living Conditions in Core Cities of the Eu. Public Policy Adm. 2012, 11, 545–562. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J.C. Democratic Decentralisation of Natural Resources: Institutional Choice and Discretionary Power Transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Adm. Dev. 2003, 23, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, I.; Chandrasekharan, C. Paths and Pitfalls of Decentralisation For Sustainable Forest Management: Experiences of the Asia-Pacific Region. In The Politics of Decentralization: Forests, Power and People; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2005; pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. The Impact of Decentralization and Urban Governance on Building Inclusive and Resilient Cities; UNDP’S Asia-Pacific Regional Centre and Un-Habitat: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, C.E. Legal Pluralism and Decentralization: Natural Resource Management in Mali. World Dev. 2008, 36, 2255–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C.; Larson, A.M. Democratic Decentralisation through a Natural Resource Lens: Cases from Africa, Asia and Latin America; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders’ Group | Organizations/Institutions/Public | Number of Interviews N = 30 | Number of Q-Sorts N = 27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government Stakeholders | Parks and Horticulture Authority | 2 | 2 | |

| Punjab Forestry Department | 2 | 2 | ||

| Lahore Walled City Authority | 2 | 1 | ||

| Metropolitan Corporation Lahore | 1 | 1 | ||

| Environmental Protection Department | 2 | 1 | ||

| Politician | 2 | 3 | ||

| Department of Planning and Development | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cantonment Board, Cantt | 1 | 0 | ||

| Non-governmental Stakeholders | Private | Expert (landscape and horticulture) | 2 | 2 |

| Lahore Chamber of Commerce | 1 | 0 | ||

| Private Developer | 1 | 1 | ||

| Civil Society | International NGOs with local partners | 2 | 2 | |

| Local Environmental group | 2 | 2 | ||

| Academia | 2 | 2 | ||

| Media | 2 | 2 | ||

| Users | 5 | 5 | ||

| Types of Claim | Elements of Discourse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontology (Set of Entities) | Agency (Degree of Agency Assigned to Entities) | Actors and Motivations | Relations | |

| Definitive (Meaning of term) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Designative (Statements of fact) | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Evaluative (Worth of something) | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Advocative (Should or should not exist) | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Factor A Efficient management | Factor B Pro/Anti administrative | Factor C Leadership/capacity building | Factor D Decentralization or Elite Capture | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 3.2 | 1.67 | 1.29 | 1.32 |

| Number of Q-sorts significantly Loading | 9 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Stakeholder groups | Government, Environmental group, Private Developers, Academia, Media, Users | Government, Experts and Users | Government, Experts and Users | Government, Environmental group, Academia |

| Stakeholders’ Group | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C | Factor D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | 2 | 3 | 2 | −1 | 1 | −1 |

| Environmental groups/NGOs | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Media | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Users | 2 | −1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Private Developers | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Academia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Experts | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| St.No. | Most Agreed and Disagreed Statements | Position in Q-Sort |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Every citizen has to contribute to green spaces, because they are using these resources or nature. They are consuming, so they must play their part. | +4 |

| 35 | I think technocrats [expert knowledge] should have a bigger role; the right man for the right job is what needed. But it is not being done. | +4 |

| 17 | In our country, not much importance is given to the environment. Once climate change was a ministry, and then it becomes a department, which again became a ministry, but toothless kind of ministry. | +3 |

| 30 | The environment is not our priority. Our policymakers want to show that stuff to the masses, on the basis of which they will get more votes in the coming elections. | +3 |

| 33 | I must say that the role of Ulemas (religious leaders) can be very positive. They are being used for the wrong things. If we engage them, I mean to say that we can use that institution as well. | +3 |

| 5 | I think there is no community culture here. They need to develop a community culture. Where there are parks, people in the neighborhood should have meetings, or they should have clubs, so they can specify that in this area this is what they need. | +2 |

| 20 | Green spaces are not adequate in the inner city. We do have funds, but people do not want to leave their places. They are ready to die for every single inch of land. | −4 |

| 22 | For a long time new parks have not been formed, as the government does not have sufficient land. | −4 |

| 23 | This is cuckoo land. These people in the inner city do not have money to maintain their houses, so how do you ask these people to make a garden on their rooves. | −4 |

| St.No. | Most Agreed and Disagreed Statements | Position in Q-Sort | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Loader | Negative Loader | ||

| 22 | For a long time new parks have not been formed, as the government does not have sufficient land. | +4 | −4 |

| 29 | I think things are getting commercialized. People go to green spaces for a walk, but they have increased the grey structure. You are bringing those kind of facilities which are damaging the true spirit of UGS. | +4 | −4 |

| 7 | Every citizen has to contribute to green spaces, because they are using these resources or nature. They are consuming, so they must play their part. | +4 | −4 |

| 14 | The local government needs to generate funds. So, if we go to any park or historical place in the western country, we have to pay for that. Why cannot we pay the fee? They can generate their own resources. | +3 | −3 |

| 11 | In our country, our bureaucratic system, there are turf wars. There is less coordination, less unity, and not a single united policy upon which everyone is agreed. | +3 | −3 |

| 37 | I have seen that our private sector is more aware than the government sector on the virtue of environmental protection, as most of the private housing schemes have green spaces as dominant features. | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | I must say that the role of Ulemas can be very positive. They are being used for the wrong things. If we engage them, I mean to say that we can use that institution as well. | −1 | +1 |

| 35 | I think technocrats should have a bigger role; the right man for the right job is what needed. But it is not being done. | −2 | +2 |

| 3 | I feel that these local group environment groups should come forward. They should take the lead and the NGOs should back them up by giving excellent solid scientific support. | −2 | +2 |

| 31 | Planning varies from area to area in Lahore. Posh areas where policymakers live and have their influence are better looked after and managed. | −3 | +3 |

| 9 | The government does not allocate enough budgets for EPD. That shows the priority of our leaders, our politicians and our government, and if they think that the environment is OK this is a western agenda, and these are rich people tantrums. | −4 | +4 |

| St.No. | Most Agreed and Disagreed Statements | Position in Q-Sort | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Loaders | Negative Loader | ||

| 1 | People do not realize what is quality of life. The Quality of life is not about taking the big house; quality of life is what is inhaling, how you feel, or is your brain at peace. That is the quality of life. | +4 | −4 |

| 13 | The civil society should take responsibility. Sometimes there is limited capacity and knowledge, so civil society can bridge that gap, and ensure that good laws are enacted and complied with. | +4 | −4 |

| 38 | I think in our system the NGOs need to interfere, because when they protest on something, it catches the attention of the media, resulting in some progress and negotiation, and so there is some betterment. | +4 | −4 |

| 23 | This is cuckoo land. These people in the inner city do not have any money to maintain their houses, so how do you ask these people to make a garden on their rooves. | +3 | −3 |

| 26 | How many people have the budgeting concept? Even if I have it, I will not want that headache. In this situation, it is unnecessary interference to involve a layman. | +3 | −3 |

| 3 | I feel that these local group environment groups should come forward. They should take the lead, and NGO should back them up by giving excellent solid scientific support. | +3 | −3 |

| 46 | When talking about the Lahore city the local environmental group is a powerful pressure group, so its activists do not let anything go wrong here easily. They are quite vigilant; parks cannot be transformed for any other purposes. | +2 | −2 |

| 36 | Green spaces are meant to be used by users, but if you ask me, if they have any role in policy making and decision making, it is not like that they should be involved in this process. | −3 | +3 |

| 37 | I have seen that our private sector is more aware than the government sector on the virtue of environmental protection, as most of the private housing schemes have green spaces as their dominant features. | −4 | +4 |

| 5 | I think there is no community culture here. They need to develop a community culture. Where there are parks, people in the neighborhood should have meetings, or they should have clubs, so they can specify that in this area what do they need. | −4 | +4 |

| St.No | Most Agreed and Disagreed Statements | Position in Q-Sort | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Loaders | Negative Loaders | ||

| 31 | Planning varies from area to area in Lahore. Posh areas where policymakers live and have their influence are better looked after and managed. | +4 | −4 |

| 43 | The green spaces and their problem cannot be solved until it is not taken at the government level. Other problems can be solved at the individual level, but for green spaces and tree plantation, government have to give some policy. Yet at city level, government has to give some policy. | +4 | −4 |

| 2 | At least all the parks in Lahore should be digitized and mapped in GIS and as online information, where people can know when its maintenance is due, and when it is done. How much is the budget, how much has been spent? There should be information sharing, so that people will come to know the government preferences towards the parks and the green spaces. | +3 | −3 |

| 16 | We have brought back the local government system again after a nine years gap, but they do not have any power. All of the authority is held by the chairman of the LDA or the chairman of the PHA. | +3 | −3 |

| 21 | If local government needs a budget, they cannot increase a few fines or fees or tax, as they need to take permission from the provincial government, and the provincial government will not allow it. They cannot generate their own funds, so the cities cannot be run | +2 | −2 |

| 30 | The environment is not our priority. Our policymakers want to show that stuff to the masses, on the basis of which, they will get more votes in the coming elections. | −2 | +2 |

| 48 | Private participation is too little. And if we talk about what the private sector is doing, it is mostly undertaking tree planting initiatives. They have no participation in policymaking. | −2 | +2 |

| 37 | I have seen that our private sector is more aware than the government sector on the virtue of environment protection, as most of the private housing schemes have green spaces as dominant features. | −4 | +4 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, R.; Lovett, J.C. Prospects of Public Participation in the Planning and Management of Urban Green Spaces in Lahore: A Discourse Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123387

Alam R, Lovett JC. Prospects of Public Participation in the Planning and Management of Urban Green Spaces in Lahore: A Discourse Analysis. Sustainability. 2019; 11(12):3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123387

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Rizwana, and Jon C. Lovett. 2019. "Prospects of Public Participation in the Planning and Management of Urban Green Spaces in Lahore: A Discourse Analysis" Sustainability 11, no. 12: 3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123387

APA StyleAlam, R., & Lovett, J. C. (2019). Prospects of Public Participation in the Planning and Management of Urban Green Spaces in Lahore: A Discourse Analysis. Sustainability, 11(12), 3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123387