Abstract

Social e-commerce has steadily emerged as a current trend for an enormous amount of Internet users. Despite the popularity and prevalence of social e-commerce, many users hesitate to disclose their information due to privacy concerns. This resistance from users impedes the development of social e-commerce enterprises. In order to help enterprises collect more user information and establish better development strategies, this research builds on the Privacy Antecedent-Privacy Concern-Outcomes (APCO) model and the theory of privacy calculus. This research investigates how the privacy antecedents of hot topic interactivity and group buying experience influence users’ privacy concerns and perceived benefits as well as how to further influence users’ information disclosure behavior. The results from 406 questionnaire responses indicate that hot topic interactivity and group buying experience have significant negative impacts on privacy concerns and significant positive impacts on perceived benefits. Privacy concerns negatively influence the behavior of information disclosure while perceived benefits positively influence the behavior of information disclosure. Based on these results, social e-commerce enterprises should promote users’ behaviors of hot topic interactivity and group buying to stimulate users’ information disclosure behavior.

1. Introduction

As a new mode of commerce, online shopping is preferred by a large number of consumers due to its convenience and its vast availability of relatively cheap commodities. The number of online shopping users is increasing rapidly as the scale of the market continues to expand, showing the strong momentum of e-commerce development. With the regularization of the consumer to consumer (C2C) network retail industry and the normalization of business to consumer (B2C) e-commerce, the commercial value of online shopping will be further highlighted.

On the other hand, social e-commerce is the new current trend. As a new derivative model of e-commerce, social e-commerce promotes the purchase and sale of goods through social interactions and user-generated content on social networking sites [1]. In 2011, Pinterest, a social network that allows users to visually share and discover new interests by posting (known as ‘pinning’ on) images or videos to their own or others’ boards (i.e., a collection of ‘pins’, usually with a common theme) and browsing what other users have pinned emerged overseas and the development of social e-commerce accelerated. Subsequently, the social e-commerce platforms represented by Xiaohong Book and Mushroom Street emerged in China. According to insufficient statistics issued in 2013, more than 20 social shopping-guide websites operated independently, and there were over 60 social shopping-guide websites when including the photo-sharing community [2]. In 2015, a report by Yibang Data showed that the purchase conversion rate of Xiaohong Book was 8–10% and that of Mushroom Street was 7–8%, rates much higher than those of ordinary e-commerce [3]. Social business is a means with which users can interact by releasing content to make enterprises achieve network sales [4]. The main purpose of social e-commerce interaction is to share, comment, and display goods that spread by word of mouth [5].

This paper focuses on e-commerce platforms based on social media in the scope of social e-commerce in China, which refers to platforms that use social media to carry out e-commerce activities, such as Sina Weibo [1]. Recent years have witnessed the rapid development of social media platforms such as WeChat, microblogging, Twitter, and Facebook. Via social media, users can get social support and share business information and shopping experiences. Social media has shown a unique advantage in e-commerce [6]. For example, through interactions between members of virtual communities, merchants can gain evaluative information of consumer shopping experiences, which in turn provides significant value for improving existing products and developing new products [7]. Therefore, social media will exert an increasingly important role and become a prominent business strategy distribution channel in the e-commerce environment. The e-commerce platform based on social media is a new business platform which combines business activities, social media technology, and community interaction [6].

However, the development of social media also creates challenges for social e-commerce. For example, the privacy of online users has been threatened. The connection of wireless and wired networks supporting e-commerce has resulted in the blowout of data resources, exposing personal information to the public.

Privacy has been sabotaged due to the disclosure of personal information. A leak of privacy is considered a major problem influencing the development of social e-commerce [8]. The majority of online users hesitate to provide their personal information immediately. Consequently, online vendors usually obtain forged personal information from customers. Statistics have demonstrated that over 50% of online customers—61% total—did not expose their credit card information online directly. Clearly, consumers have great privacy concerns about disclosing information. However, customer information has been used by merchants to produce personalized offerings and improved services. To succeed in commerce, firms must collect consumer information [8]. Enterprises in the social e-commerce environment attempt to collect, store, and exchange data of consumers’ personal information to analyze consumers’ preferences, trends of marketing, and so on. As a result, they can develop better strategies to increase sales [9].

As social networking sites (SNSs) increase in popularity among teens, online marketers want to seize this opportunity and gain access to more teenagers via SNSs and other social media, thus collecting valuable information [10]. Both business intelligence software and personalized web services require massive collection of personally identifying information [11]. Massive amounts of information are needed by companies to establish a relationship with current customers and build new business for the sake of survival [12]. E-business can save the cost of offline face-to-face interaction. Companies can use the customer information obtained digitally to provide personalized services that both promote value and customer loyalty. The infrastructure of information technology (IT), together with the information contained, serves as the key factor for all e-business initiatives [13]. Ultimately, privacy concerns significantly influence the development of social e-commerce. If companies can decrease consumers’ privacy concerns, they can increase their opportunities for success, thus promoting the overall progress of social e-commerce. Therefore, understanding the factors that influence privacy concerns of consumer information disclosure and the impacts of privacy concerns are of great significance.

This study explores how the mechanisms of hot topic interactivity and group buying experience influence privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and users’ information disclosure behavior in social e-commerce. This research provides both theoretical and practical contributions. First, this paper has studied privacy antecedents from the perspective of hot topic interactivity and group buying experience. Second, we contribute to the Privacy Antecedent-Privacy Concern-Outcomes (APCO) model and the theory of privacy calculus by clarifying the relationship between privacy antecedents and the behavior of information disclosure and revealing its path process. Moreover, this paper provides managers with advice on how to reduce users’ privacy concern, enhance users’ perceived benefits, and stimulate users’ information disclosure behavior through social e-commerce.

This study provides feasible suggestions for enterprises to collect more information from users and formulate better market strategies, which is conducive to the long-term operation and sustainable development of enterprises. At the same time, a series of measures taken by enterprises on social e-commerce platforms also bring considerable economic benefits to platforms, which promotes the sustainable development of social e-commerce platforms as well.

2. Literature Review

2.1. APCO Model

Smith, et al. [14] introduced a macro model known as the Antecedents-Privacy Concern-Outcomes (APCO) model, which summarized almost all empirical assessments of privacy. In the same period, Li [15] and Belanger and Crossler [16] did similar research, and their conclusions were similar to those of Smith, Dinev and Xu [14] in classifying the variables considered in previous studies. Antecedents, usually individual traits or contextual factors, lead to individuals forming privacy concerns, causing behavioral outcomes based on individuals’ information processing.

Considering the aforementioned macro models, the following conclusions can be drawn [14,15,16]: (1) various factors influence privacy concerns at different levels; (2) many factors play a role in mediating and moderating relationships between privacy concerns, intentions, and behaviors; and (3) many privacy-related intentions and behaviors (e.g., disclosures) can be observed at many different levels (such as individual and society).

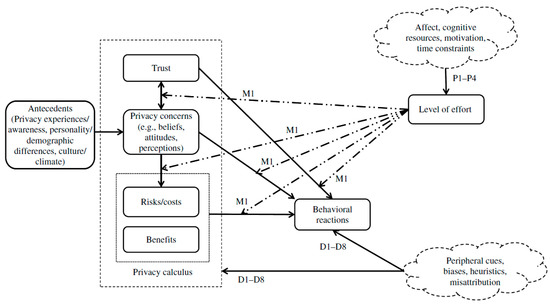

Polites and Karahanna [17] offered a more comprehensive explanation of privacy-related behaviors that involves important elements ignored by previous theories, including the level of cognitive effort consumed by individuals and several factors influencing the level of effort and external influences (e.g., peripheral cue and biases) that may affect constructs in the APCO macro model. Figure 1 presents these important additions to the APCO with the addition of two “clouds” that influence privacy-related attitudes and behaviors.

Figure 1.

Enhanced Privacy Antecedent-Privacy Concern-Outcomes (APCO) model.

The upper “cloud” represents a set of contextual and cognitive constraints that determine the level of processing effort, the effects of which are shown with arrows and denoted by P1–P4 in Figure 1. The lower “cloud” shows important external influences that have been proven by researches in the fields of behavioral economics and psychology; biases, heuristics, peripheral and misattributions of privacy-related attitudes and behaviors directly influence individuals’ privacy calculus and behavioral reactions (shown with arrows and denoted by D1–D8).

2.2. The Theory of Privacy Calculus

The theory of privacy calculus, as proposed by Culnan and Armstrong [12], refers to the calculation of the balance between perceived benefits and privacy concerns by users during the process of information disclosure. This theory consists of privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and information disclosure behavior. Privacy concerns reduce the behavior of information disclosure, while perceived benefits promote the behavior of information disclosure [18]. According to the theory of utility maximization: U(x) = Benefit − Cost. By maximizing utility and making consumers willing to disclose information, consumers’ perceived benefits increase and privacy concerns decrease. Xu, et al. [19] analyzed the behavioral intentions of users to disclose their privacy according to the theory of privacy calculus, indicating that benefits must exceed costs to ensure the motivation of self-disclosure. The research carried out by Chen [20] indicated that as privacy concerns of users increased, willingness to disclose personal information decreased. The empirical research of Wang, et al. [21] suggested that users’ perceived benefits are positively correlated with the intention of disclosing personal information.

2.3. The Combination of these Theories

In recent years, several studies have proposed more comprehensive models in the field of online privacy and information disclosure, among which the Privacy Antecedent-Privacy Concern-Outcomes (APCO) model [14] is widely used. Both versions of the APCO model focus on connections among individual variables related to online privacy. Based on APCO theory, this paper proposes a model. Privacy antecedents include hot topic interactivity and group buying experience. Both hot topic interactivity and group buying experience are common virtual experiences related to privacy for users on social e-commerce platforms, and they are in accordance with the characteristics of social e-commerce. What is more, compared with the interaction between two people, the interaction in the area of hot topic can reflect the social groups of social e-commerce better, help users gain more useful information, and enhance reputation. Group buying is a unique function of social e-commerce compared to e-commerce; users can make use of powerful social groups to engage in group buying for the purpose of getting the best price. Therefore, in the current study, they are selected as antecedents. PC refers to privacy concern and outcomes include the behavior of information disclosure, which helps explore how the mechanism of hot topic interactivity and group buying experience influence privacy concerns and the behavior of information disclosure. In this model, privacy concerns (PCs) play a role as both a dependent variable (for antecedents) and an independent variable (explaining behavior) [22].

Additionally, there have been frequent applications of the theory of privacy calculus in former research on SNS and customer behavior in social e-commerce. This theory contains the three variables of privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and the behavior of information disclosure and explains the relationship between privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and the behavior of information disclosure, respectively. However, the APCO model lacks the variable of perceived benefit, but users consider the risks and benefits before information disclosure, so privacy concerns and perceived benefits are critical to information disclosure. The APCO model also does not point out the specific outcome, as in the behavior of information disclosure. Moreover, there is no explanation for the relationship between privacy concerns and the behavior of information disclosure as well as the relationship between perceived benefits and the behavior of information disclosure. Therefore, the theory of privacy calculus is a strong complement to the APCO model. It can be said that the combination of these theories provides a solid theoretical basis for the current research, thus guiding the direction for the establishment of follow-up models on privacy in different backgrounds.

Using a combination of the two theories above, this study explores how the mechanisms of hot topic interactivity and group buying experience influence privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and users’ information disclosure behavior in social e-commerce. In the theory of privacy calculus, the behavior of information disclosure is determined by privacy concerns and perceived benefits. At the same time, this study regards the behavior of information disclosure as the “outcome” in the APCO model and considers privacy concern as the “PC” in the APCO model. Moreover, the current research regards hot topic interactivity and group buying experience as “privacy antecedents” in the APCO model from the perspective of users’ virtual privacy experiences. In addition, this study views privacy tag as the moderating variable because it is a common feature that users can use when engaging in hot topic interactivity and participating in group buying on the social e-commerce platforms, and its appearance helps reduce users’ privacy concerns.

2.4. Social E-Commerce

Social media is a tool for socialization and information sharing, and its increasing popularity has generated a new form of e-commerce named social e-commerce [23]. Social e-commerce is a new derivative model of e-commerce, which promotes the purchase and sale of goods through social interactions and user-generated content on social networking sites [1]. Different from traditional e-commerce, social e-commerce is e-commerce that involves social media [6], which is mainly affected by user contributions and social interactions [23,24].

At present, the commercial influence of social commerce is brilliantly noticeable to different corporations. Based on the view of Liang et al. [23], the two leading trends in social e-commerce are the addition of commercial features to social capabilities and social networking sites. The third trend in social e-commerce is that traditional offline companies are beginning to use social media widely for customer relationship management, brand communication, product promotion, and social shopping.

Turban, King, Lee, Liang and Turban [5] collected 22 different definitions of social e-commerce, concluding the following characteristics of social e-commerce: reputation, credible suggestions, and friends to help buy. Social e-commerce has the three crucial attributes of media attribute, social attribute, and business attribute. The user’s own product-related content in social e-commerce has become the main feature of its media attribute. UGC (user generated contents), also known as UCC (user created content), refers to any form of texts, pictures, and videos published in networks by users, which is a spontaneous form of building and propagating information in the era of web 2.0 [25]. The existence of a social attribute in social e-commerce reduced the cost of search and dissemination of commodity information and achieved the matching of commodity information and consumers in quite a short period, achieving an efficient connection of consumers, e-commerce, and platforms [26]. The rewards system of the business attribute made social e-commerce popular. From the perspectives of consumers, they can get rewards if they share their experiences and make comments. From the view of the platform, it can offer the information of users to other e-commerce websites, thus obtaining a certain commission [27].

2.5. Information Disclosure

Recently, many studies have concentrated on information disclosure on SNSs [28], which describes a large amount of personal information individuals share on platforms (such as personal pictures and videos [29], dynamic updates of daily events [30]). When people become socially active, they even expose others’ information. Abundant research concentrates on the motivations of personal information disclosure on social networking sites [31].

Chen and Sharma [32] first demonstrated the connections between self-disclosure and attitude formation through the self-disclosure of Facebook users. Previous research found that attitude can positively influence the extent of self-disclosure. Later, more and more studies have pointed out that the interaction between perceived costs and perceived benefits play an important role [33]. Xu, et al. [34] promoted the idea that online self-disclosure is founded upon the theory of planned behavior (TPB), which focuses on the factors that influence privacy disclosure, including sensitivity, information control, privacy concern, perceived risks, and perceived benefits. The results of that research shows that a higher effect over the users’ intention of SNS would be generated through perceived benefits compared with personal privacy concerns [34]. Ampong, Mensah, Adu, Addae, Omoregie and Ofori [33] explored the influencing factors of personal information disclosure on SNSs from the perspective of flow and privacy. However, in most of the existing studies, there are fewer social e-commerce areas involved, and the influencing factors of information disclosure behavior are extremely broad.

Currently, the majority of research about the information disclosure of users is based upon the privacy calculus model, which is closely associated with exchange theory [35,36]. In exchange for social benefits, individuals are willing to expose their personal information [12,37].

2.6. Privacy Concerns

Privacy concerns represent how users worry that their personal information might be threatened online, such as surveillance, tracking, and thefts [38], which may cause some negative effects in the digital world [39]. This demonstrates the response of users about the perceived possibility of the leakage of personal information and the potential abuse of personal information. Importantly, users who are very sensitive about their privacy may feel reluctant to disclose any personal information on any social media website [40] or to alternatively submit false information [41].

In terms of factors influencing privacy concerns, Xu, Michael and Chen [34] found that privacy concerns were influenced by subjective norm, information control, and information sensitivity. Recently, Koohikamali, et al. [42] concluded that previous privacy invasion, sensitive information disclosure control, and social identity exerted significant impact on privacy concerns. Bansal, et al. [43] showed that personality including extroversion, agreeableness, emotional instability, conscientiousness, and intellect could have great effects on privacy concerns.

2.7. Perceived Benefits

In the majority of related studies that focused on online commercial transactions, perceived benefits were considered as a kind of free service. An experiment was conducted by Yang and Wang [44] in which discounts were presented as a kind of compensation if users were willing to disclose their individual information on the Internet. It has been concluded by Phelps, et al. [45] that users’ willing disclosure of personal information is somehow like better purchasing recommendations and a contraction in shopping time.

In general, a perceived benefit can be considered as a type of expected return of information disclosure, such as a personal image [46], entertainment [46], customized and personalized services [8,47,48], convenience [49], and establishing and maintaining social relationships [50].

Wang, Duong and Chen [21] found that personalized service and self-presentation have great impacts on perceived benefits. Zlatolas, et al. [51] believed that privacy policy had an impact on perceived benefits.

Numerous studies describe factors that influence privacy concerns and perceived benefits, but these studies only isolate single factors, rather than multiple factors. In addition, previous studies did not fully consider the background of the research. Consequently, in this paper, hot topic interactivity and group buying experience from the perspective of users’ virtual experience are used as independent variables under the social e-commerce environment.

2.8. Privacy Antecedents

Hot topic interactivity and online group buying are the most popular functions for users on social e-commerce platforms. As two important components of users’ privacy antecedents, they are related to privacy disclosure, showing great significance in the study of privacy disclosure.

2.8.1. Hot Topic Interactivity

Content creation and sharing, which includes posting shopping messages and boasting about shopping experiences, bonds customers with each other [23]. When it brings them benefits, customers are more likely to interact with others online. Through interaction in social e-commerce, customers can gather the information they need to make decisions. Then, customers feel that they should offer valuable information in return [52].

McMillan [53] defined interactivity as a mediating interaction between individuals from the perspective of interpersonal communication. Some other scholars gave the definition of interactivity from a mechanical perspective [54]. In general, the concept of interactivity can be subdivided into three types: human–to–system interactivity, human–to–document interactivity, and human–to–human interactivity [53].

In this research, hot topic interactivity is defined as the communication conducted by customers over a popular topic, which engages life experience and commodity recommendation, among other qualities [55].

2.8.2. Group Buying Experience

In this study, the concept of group buying experience refers to the customers’ prior experiences with gathering with other customers who share the same needs and then balancing their collective bargaining power to decrease the price of services or products [56]. In the social e-commerce environment, group buying usually takes the form of inserting commodity links into social media.

The main value of online group buying is to unify and bond individuals who share the same demands to buy at a lower price through obtaining volume discounts, which is usually the privilege of bulk buyers [57,58]. The research carried out by Chen, et al. [59] unveiled that online group buying generates more benefits for customers compared with traditional shopping channels. Customers who conduct online group-buying activities are more likely to decrease perceived risks and uncertainties [56].

In this work, hot topic interactivity and group buying experience are employed as independent variables that represent users’ privacy antecedents. At the same time, they are well integrated with the social e-commerce environment.

2.9. Privacy Tag

As a tool that users can use to control the range of their information disclosure [60], the privacy tag offers users a better understanding of the privacy relationships they choose to enter or evade and helps them choose without reading privacy policies [60]. Content posted on social e-commerce platforms can be only visible to one individual or only visible to a groups of people. Users can name groups as tags and they can choose relevant tags when they interact with other users, then the information will be sent to the target objects. Therefore, users can increase the sense of privacy security and decrease privacy concerns [61].

In previous studies, many scholars have explored the relationship between the privacy tag and privacy concerns in the context of social networking sites. The privacy tag has received less attention in the field of social e-commerce and there are relatively few studies on the impact of privacy tag on the relationship between privacy antecedents and privacy concerns. Therefore, it is innovative to select privacy tag as a moderating variable in this paper.

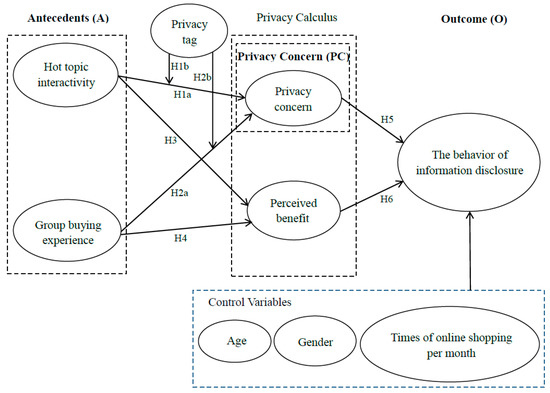

3. Hypothesis Development and Model

This study applies the theory of privacy calculus and the APCO model to the social e-commerce environment (Figure 2). This research model found a close relationship between the behavior of information disclosure, drawn from the outcome in the APCO model, privacy concerns, drawn from PC in the APCO model, and perceived benefits, drawn from the theory of privacy calculus. In this paper, hot topic interactivity and group buying experience are adopted as antecedents in the APCO model. From the perspective of users’ virtual experiences, it can be seen that there are two categories of social support and flow in the virtual experiences [23,62]. As a multidimensional construct, social support refers to the perception or experience of individuals of being helped, responded to, and cared for by other people coming from the same social group [23]. The flow depicts the enjoyable and optimal experience people enjoy when they are engaged in activities [63,64], during which people reduce self-awareness and give all their attention [33]. Hot topic interactivity relates to social support because it represents people’s experience of mutual care, mutual response, and mutual help within social groups. Separately, group buying experience relates to flow since it captures people’s experience of total involvement.

Figure 2.

The theoretical model.

Both hot topic interactivity and group buying experience are common virtual experiences for users on social e-commerce platforms, and they reflect the characteristics of social e-commerce, such as reputation, credible suggestions, and friends to help buy. For instance, users can post useful information in the area of hot topic to gain respect and enhance their reputation. Users can ask for help from others in the area of hot topic to gain credible suggestions. Users can let friends help buy to get the best price. Simultaneously, these concepts are related to users’ privacy. What is more, compared with the interaction between two people, the interaction in the area of hot topic can reflect the social groups of social e-commerce better, help users gain more useful information, and enhance reputation. Group buying is a unique function of social e-commerce compared to e-commerce; users can make use of the powerful social groups in the social e-commerce to make group buying for the purpose of getting the best price. It is important that the above literature reflects their relevance to privacy concerns and perceived benefits. Therefore, in the current study, they are selected as antecedents. Moreover, this paper introduces the privacy tag as the moderating variable and presents age, gender, and frequency of online shopping per month as control variables [65]. The research showed that women’s information disclosure behaviors were higher than that of men. Age had a negative impact on information disclosure behavior in which age was divided into six categories: 19 years and under, 20–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and 60 years and above. Frequency of online shopping per month had a positive impact on information disclosure behavior in which frequency was divided into four categories: less than one time, one to two times, three to four times, and more than four times.

3.1. Privacy Antecedents and Privacy Calculus

3.1.1. Hot Topic Interactivity and Privacy Concerns

Hot topic interactivity refers to communication conducted by customers over a popular topic, which engages life experience and commodity recommendation [55]. Privacy concerns are the concerns of users that their personal information online might be threatened [66]. Customers interact with others in the area of hot topic via content sharing and creation about their shopping experience. Additionally, messages about life experiences and shopping experiences are often posted. Such communication provides emotional support and information support between customers [23]. People who feel that they are supported are more likely to reciprocate trust in others; they feel safe and relaxed on the social e-commerce platforms, which makes them less concerned about privacy disclosure [23]. In summary, hot topic interactivity gives users favorable information, emotional support, a sense of trust, and reduced privacy concerns. Therefore, it can be hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1a.

Hot topic interactivity will have a negative effect on privacy concerns.

3.1.2. Hot Topic Interactivity, Privacy Tag, and Privacy Concerns

Hot topic interactivity refers to the communication conducted by customers over a popular topic, which engages life experience and commodity recommendation [55]. Privacy tag is a tool that users can employ to control the range of their information disclosure [60]. Privacy concerns describe the concerns of users that their personal information online might be threatened [66]. Users can set groups as tags, which means they can choose relevant tags when they interact with other users. Therefore, users can increase the sense of privacy security and further decrease privacy concerns through privacy tags [61]. In summary, it has been assumed that hot topic interactivity has a negative impact on privacy concerns; that is, users’ privacy concerns are decreased as hot topic interactivity is increased. When there are privacy tags on social e-commerce platforms, users feel a larger sense of security for their high hot topic interactivity and they feel that it is worthwhile to have hotter topic interactivity on the social e-commerce platforms. Then, users take high hot topic interactivity as an important activity on the social e-commerce platforms. As a result, users’ privacy concerns are lessened because hot topic interactivity is expanded, indicating that the negative impact of hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns will be larger. Then, it involves the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b.

The privacy tag will moderate the relationship between hot topic interactivity and privacy concerns. Therefore, when the privacy tag is presented, the negative effect of hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns is larger. However, when the privacy tag is not presented, the negative effect of hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns is smaller.

3.1.3. Group Buying Experience and Privacy Concerns

The concept of group buying experience refers to customers’ prior experiences gathering with other customers who share the same demands and then making full use of their collective bargaining power to decrease the price of services or products [56]. Privacy concerns are the concerns of users that their personal information online might be threatened [66]. Group buying experience is closely associated with group negotiation, in which the quality of an online purchase is promoted by gathering a larger quantity of individuals to form a group. Afterwards, negotiations are implemented to obtain more favorable prices from sellers [67]. Li, et al. [68] found that group buying is favored by both sellers and buyers and is a mutually beneficial activity. Therefore, the function of group buying is a proper cause of customers to consider that social e-commerce offers convenience for them, and then their affection for social e-commerce platforms will increase, while privacy concerns decrease. Additionally, customers who take part in online group buying activities have the potential to establish friendly relationships with sellers. Some other customers might search for a way to decrease the risks and uncertainties present in online group buying activities [56]. In summary, group buying can bring users the best prices. Users who have more group buying experiences have a greater tendency to feel that social e-commerce providers consider mutual benefits between them and the users. Therefore, users’ favor for social e-commerce platforms will increase and privacy concerns will decrease accordingly. Hence, it can be hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2a.

Group buying experience will exert a negative influence on privacy concerns.

3.1.4. Group Buying Experience, Privacy Tag, and Privacy Concerns

The concept of group buying experience refers to customers’ prior experiences gathering with other customers who share the same demands and then making full use of their collective bargaining power to decrease the price of services or products [56]. Privacy tag is a tool that users can employ to control the range of their information disclosure [60]. Privacy concerns are the concerns of users that their personal information online might be threatened [66]. With privacy tags, users can freely choose the object of information disclosure. When users join in group buying, the use of privacy tags helps them post information to relevant groups according to their own wishes, and thus they can further decrease privacy concerns [69]. In summary, it has been assumed that group buying experience has had a negative impact on privacy concerns; that is, users’ privacy concerns are reduced because of more group buying experiences. Further, when there are privacy tags on social e-commerce platforms, users feel a larger sense of security for their frequent participation in group buying. Then, users feel that it is worthwhile to participate in group buying frequently on social e-commerce platforms. Then, they frequently participate in group buying as an important activity on social e-commerce platforms. Consequently, users’ privacy concerns decrease as group buying experiences increase, suggesting that group buying experiences will have a greater negative impact on privacy concerns. Then, it can be hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2b.

The privacy tag will moderate the relationship between group buying experience and privacy concerns. In this case, when the privacy tag is presented, the negative effect of group buying experience on privacy concerns is more significant. When the privacy tag fails to be shown, the negative effect of group buying experience on privacy concerns is less significant.

3.1.5. Hot Topic Interactivity and Perceived Benefits

Hot topic interactivity refers to the communication conducted by customers over a popular topic, which engages life experience and commodity recommendation [55]. Perceived benefits indicate an expected return from information disclosure, which might include personal images and monetary interests [46], customized and personalized services [8,47,48], and convenience [49]. Interactivity offers a convenient venue for the creation of social support, content exchange, contributions of support among customers, and self-presentation [23]. The interactivity feature in social e-commerce enables customers to depict a satisfying self-image [62]. With hot topic interactivity, consumers feel that they obtain useful information, friendships, and a satisfying self-image, among other benefits [70]. Users who have hotter topic interactivity feel that they will obtain more favorable information, make more friends, and shape better self-images, indicating that the perceived benefits expand. Consequently, it can be hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3.

Hot topic interactivity will have a positive effect on perceived benefits.

3.1.6. Group Buying Experience and Perceived Benefits

The concept of group buying experience refers to customers’ prior experiences gathering with other customers who share the same demands and then making full use of their collective bargaining power to decrease the price of services or products [56]. Perceived benefit refers to a kind of expected return of information disclosure, such as personal image and monetary interests [46], customized and personalized services [8,47,48], and convenience [49]. For customers, the main value of online group buying is to buy at a lower price through obtaining volume discounts, which is usually the privilege of bulk buyers. Online group buying unifies and bonds individuals who share the same demands to make full use of their collective bargaining power to bargain with online sellers [57,58]. Research by Chen, Chen, Kauffman and Song [59] demonstrates that online group buying generates more benefits for customers than traditional shopping channels. Users participate in group buying for various reasons. Additionally, they might integrate agreements to obtain the maximum joint benefits, which can be mostly elusive [71]. In summary, users who have more group buying experiences feel that they will obtain the best prices and make more friends, which suggests that the perceived benefit will be more. Therefore, it can be hypothesized:

Hypothesis 4.

Group buying experience will have a positive effect on perceived benefits.

3.2. Privacy Calculus and Outcomes

3.2.1. Privacy Concerns and the Behavior of Information Disclosure

Privacy concerns are the concerns of users that their personal information online might be threatened [66]. The behavior of information disclosure involves the release of information that is usually protected or private [28]. Privacy concerns serve as the key antecedent of behavioral reaction over information disclosure [14], demonstrating that understandings of personal privacy influence online behavior in practice [34]. Users with extreme privacy concerns tend to reject the submission of personal information [41] to social network sites [40]. To conclude, the higher the privacy concerns of users, the less information disclosure behavior they enact, which avoids possible threats to personal information. Thus, it is further supposed that privacy concerns have negative affectivity on the behavior of information disclosure.

Hypothesis 5.

Privacy concerns will negatively affect the behavior of information disclosure.

3.2.2. Perceived Benefits and the Behavior of Information Disclosure

Perceived benefits refer to a kind of expected return of information disclosure, such as personal image and monetary interests [46], customized and personalized services [8,47,48], and convenience [49]. The behavior of information disclosure is a kind of information sharing behavior involving the disclosure of information which is usually protected or private [28]. Based on a study conducted by Forman, et al. [72], people who register and participate in social networks achieve community attachment. According to Forman, Ghose and Wiesenfeld [72], the reasons that people disclose their personal information include attachment to relevant communities and easier identification. A large proportion of customers will relinquish some of their personal information for perceived benefits generated from information disclosure if they know that they can obtain benefits, such as personal image and monetary interests [46], entertainment [46], customized and personalized services [8,47,73], and convenience [49].

Many studies focus on the relationship between the online behavior of customers and perceived benefits. For instance, shoppers are more likely to reveal their personal information if it means that they will get online discounts or promotions [37,74]. Boyd and Ellison [75] concluded that perceived benefits exerted a positive influence on using social network sites. In summary, the higher the perceived benefits of users, the higher the amount of information disclosure behavior with the aim to gain more benefits. According to this research, the behavior of information disclosure is positively influenced by perceived benefits.

Hypothesis 6.

Perceived benefits will make a positive impact on the behavior of information disclosure.

4. Methodology

The questionnaire in this study lasted for 10 consecutive days because enough samples were collected, during which the participants were solicited by different online social media channels such as WeChat, QQ, microblogging, and a questionnaire site. Since the background of this research was e-commerce platforms based on social media, such as Sina Weibo, users of these online social media platforms were more experienced with hot topic interactivity, group buying, and information disclosure. Therefore distributing questionnaires through these online social media channels made the samples more representative. What is more, the beginning of the questionnaire illustrated the definition of social e-commerce and the variables involved in this study. Each part of the questionnaire emphasized the background of social e-commerce; this avoided the variance of understanding on social e-commerce and variables among users and ensured that the platforms the participants were filling the questionnaire out for were social e-commerce platforms. A total of 452 questionnaire responses were initially collected. However, since some of the questionnaires answered the set of common-sense questions incorrectly, they were considered as not seriously answered and were deleted. As a result, a total of 406 valid questionnaires were finally used for analysis. The sample included 223 females (54.9%) and 183 males (45.1%). The largest group of participants were users aged between 20 and 29 years (30%), followed by 30–39 years (24.9%), 40–49 years (20%), 19 years or less (12.1%), 50–59 years (7.9%), and 60 years or more (5.2%).

In addition, this study performed an analysis of variance for age, gender, times of online shopping per month, and the core variables of hot topic interactivity, including group buying experience, privacy concerns, and perceived benefits, respectively. There was no significant difference between age and core variables (p > 0.05) or gender and core variables (p > 0.05). There was a significant difference between times of online shopping per month and core variables (p < 0.05).

5. Analysis Results

5.1. Reliability Analysis

Reliability analysis use the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient to examine the consistency of the survey variables in each measurement item (Table 1). And the measurement items can be seen in Appendix A. Hair et al. [76] believed that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient must be greater than 0.70 for good confidence in variables. The measurement scales of all samples achieved reliability scores greater than 0.70, indicating adequate support for measurement reliability of each sample.

Table 1.

Reliability analysis.

5.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The exploratory factor analysis of all variables’ scale was performed using SPSS22.0. The scale was subjected to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Table 2 shows the results.

Table 2.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test.

The table above illustrates that the KMO measure is 0.903, which is greater than 0.7. Meanwhile, Bartlett’s test of sphericity provides significance (p < 0.001), indicating that the data obtained satisfies the premise of factor analysis. During the process of factor extraction, principal component analysis was adopted in the research and the maximum variation of the rotary method was used to estimate the load of the factor. Factor analysis was carried out with the eigenvalue greater than 1. The results can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

The results of factor analysis.

Table 3 indicates that the results of factor analysis were a total of six factors: privacy concern (PC), perceived benefit (PB), behavior of information disclosure (BID), privacy tag (PT), group buying experience (GBE), and hot topic interactivity (HTI). The explanatory ability of each factor was 42.058%, 10.095%, 8.292%, 7.169%, 6.426%, and 5.680%, respectively. The total interpretation ability reached 79.719%, which, at more than 50%, illustrates that these factors have been well represented. The load factor of every measurement item was over 0.5 while the cross load was no more than 0.4 when each item was finally classified into each relative factor. Therefore, it can be seen that various factors of this study have excellent structural validity.

The data in this study may have common methodological bias due to the same source. The common method bias is tested through conducting the Harman single factor analysis [77]. Exploratory factor analysis is used for factor loading statistics of all variables. The results are shown in Table 4. There is a total of six factor eigenvalues greater than 1. The total variance explained of the single factor extracted is 42.058%, being smaller than the critical standard (50%), indicating that there is no serious common method bias in the data collected [78].

Table 4.

Total variance explained.

We also used the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) comparison method to compare the chi-squared and degree of freedom of the single-factor model and the multi-factor model. The results are shown in Table 5, the chi-squared difference between the two models was significant (Δχ2 = 5862.375, ΔDF = 36, p < 0.01), indicating that there was no serious CMV [79]. The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the single-factor model did not fit the data (CMIN/DF = 29.419, RMSEA = 0.265). This suggests that CMV is unlikely to severely confound the interpretations of the results [80].

Table 5.

Models comparison.

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 6 presents the comparisons between the multi-factor models and single-factor model.

Table 6.

Comparison of confirmatory factor analysis.

Based on the above table, the fitting indexes of the six-factor model are better than that of the other five comparative models (χ2 = 315.638; χ2/df = 1.814; RMSEA = 0.045; GFI = 0.935; NFI = 0.949; IFI = 0.976; CFI = 0.976; RMR = 0.112). Most of the fitting indicators conformed to the standards of general research, therefore, this six-factor model can be assumed as a good fit. By examining both the factor loadings of indicators related with each construct and the average variance extracted (AVE), convergent validity was confirmed. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to calculate the factor loadings. The AVE values between 0.632 and 0.748, which are more than the 0.5 threshold value, have been presented in Table 7 [81]. The factor loadings between 0.766 and 0.891, which are all statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level, strongly support the presence of convergent validity [82].

Table 7.

Convergent validity.

This study used the AVE square root method to evaluate the discriminant validity of the factors. Fornell and Larcker [81] proposed that the square root of AVE exceeded the correlation coefficient of the lower triangle in the correlation matrix of all samples, which means there is discriminant validity among factors. The correlation matrix can be found in Table 8, which shows that the diagonal AVE square root of each factor is greater than the correlation coefficient of the lower triangle. Therefore, the study has discriminant validity.

Table 8.

Discriminant validity.

5.4. Structural Equation Modeling

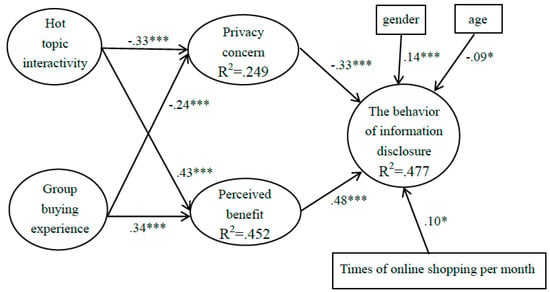

Given that the relevant measure has achieved good reliability and validity, this research adopts AMOS 23.0 to establish complete structural equation modeling (SEM) (Figure 3) and to verify and explore the relationship between these variables.

Figure 3.

Structural equation modeling.

SEM was applied as the major data analysis method. Different from regular regression analysis, a set of interrelated issues have been collectively explored through the simultaneous test of the interplay between endogenous (dependent) constructs and exogenous (independent) constructs. Comparatively, SEM offers more rigorous and dynamic analyses for the model fitting.

Table 9 presents the fit strength for the structural model and the desirable range of fit indices. All fit indices meet the recommended threshold criteria. Consequently, the fit to structural equation modeling is found to be satisfactory.

Table 9.

The fit degree of structural equation modeling.

According to Table 10, hot topic interactivity has a significant negative impact on privacy concerns (β = −0.327, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1a. Further, group buying experience has a significant negative impact on privacy concerns (β = −0.244, p < 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 2a. Hot topic interactivity has a significant positive impact on perceived benefits (β = 0.429, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 3. Group buying experience has a significant positive impact on perceived benefits (β = 0.342, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 4. Privacy concerns have a significant negative impact on the behavior of information disclosure (β = −0.326, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 5. In addition, perceived benefits have a significant positive impact on the behavior of information disclosure (β = 0.479, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 6.

Table 10.

Path coefficients.

5.5. Mediation Test

In this paper, AMOS 23.0 is employed for path analysis, and the bootstrap method is adopted to make a confirmation. Studies have demonstrated that the confidence interval of the bootstrap method does not contain zero, and the corresponding indirect effect exists [83,84]. In AMOS 23.0, the bootstrap method is adopted to run 5000 times and obtain the level value at the 95% confidence level (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Mediation Ttst.

The non-standardized mediation effect of privacy concerns between hot topic interactivity and the behavior of information disclosure is 0.097. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals tested by the bias-corrected bootstrap method and percentile bootstrap method do not contain zero, indicating the existence of the indirect effect.

The non-standardized mediation effect of privacy concerns between group buying experience and the behavior of information disclosure is 0.076. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals tested by the bias-corrected bootstrap method and percentile bootstrap method do not contain zero, indicating the existence of the indirect effect.

The non-standardized mediation effect of perceived benefit between hot topic interactivity and the behavior of information disclosure is 0.187. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals tested by the bias-corrected bootstrap method and percentile bootstrap method do not include zero, indicating the existence of the indirect effect.

The non-standardized mediation effect of perceived benefit between group buying experience and the behavior of information disclosure is 0.155. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals tested by the bias-corrected bootstrap method and percentile bootstrap method do not contain zero, indicating the existence of the indirect effect.

5.6. Moderating Effect

The results of the moderating effect are shown in Table 12. From the first step, hot topic interactivity and group buying experience have significant negative impacts on privacy concerns. From the second step, after adding the privacy tag on the basis of the first step, hot topic interactivity, group buying experience, and privacy tag have significant negative impacts on privacy concerns. From the third step, it can be seen that after adding (hot topic interactivity × privacy tag) and (group buying experience × privacy tag) based on the second step, (hot topic interactivity × privacy tag) have a significant negative impact on privacy concerns (β = −0.091, p < 0.01), indicating that the privacy tag has a significant moderating impact on the effect of hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns, supporting Hypothesis 1b. (Group buying experience × privacy tag) has a significant negative impact on privacy concerns (β = −0.084, p < 0.01), indicating that the privacy tag shows a significant moderating effect on the effect of group buying experience on privacy concerns, supporting Hypothesis 2b.

Table 12.

Moderating effect of PT on HTI, PC and GBE, PC.

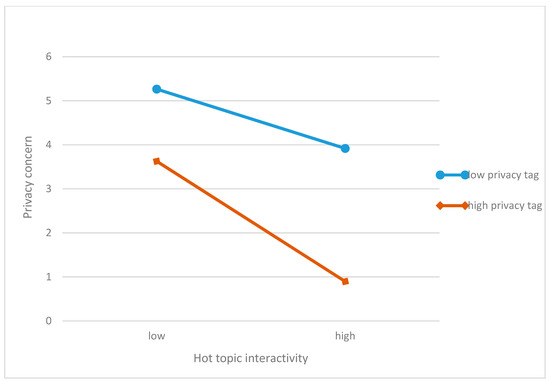

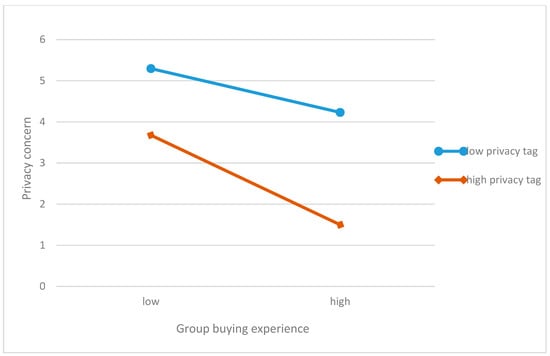

In order to intuitively reflect the moderating effect of the privacy tag on the relationship between privacy antecedents and privacy concerns, we use the method of Aiken and West [85] to draw the moderating effect figures (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of privacy tag on hot topic interactivity and privacy concern.

Figure 5.

Moderating effect of privacy tag on group buying experience and privacy concern.

From Figure 4, we can see that the negative effect of hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns is continuously strengthened with the higher degree to which the privacy tag is presented on social e-commerce platforms. Specifically, when the privacy tag on the platforms is presented to a higher degree, the negative impact of users’ hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns is greater; additionally, when the privacy tag on the platforms is presented to a lower degree, the negative impact of users’ hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns is less. From Figure 5, we can see that the negative effect of group buying experience on privacy concerns is continuously strengthened with the higher degree to which the privacy tag is presented on social e-commerce platforms. Specifically, when the privacy tag on the platforms is presented to a higher degree, the negative impact of users’ group buying experience on privacy concerns is greater; and when the privacy tag on the platforms is presented to a lower degree, the negative impact of users’ group buying experience on privacy concerns is less.

6. Discussions and Implications

6.1. Discussions

Social e-commerce platforms play an important role in the lives of most individuals. The popularity of social e-commerce has ushered in new issues concerning privacy and information disclosure online. This research aims to identify a model to determine how hot topic interactivity, group buying experience, and privacy tags affect privacy concerns and perceived benefits, and how privacy concerns and perceived benefits influence the behavior of information disclosure. The model was established according to previous studies regarding privacy and information disclosure. To confirm the model, 406 valid questionnaire responses were used to conduct the analysis. The research model was confirmed with the support of SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 23.0.

The results show that hot topic interactivity has a significant negative influence on privacy concerns. Group buying experience also influences privacy concerns significantly and negatively, while hot topic interactivity and group buying experience have a significant positive impact on perceived benefits. Privacy concerns have a significant negative influence on the behavior of information disclosure, while perceived benefits have a significant positive influence on the behavior of information disclosure. The indirect mediator effect of privacy concerns on the effect of hot topic interactivity on the behavior of information disclosure exists. The indirect mediator effect of privacy concerns on the effect of group buying experience on the behavior of information disclosure exists. The indirect mediator effect of perceived benefits on the effect of hot topic interactivity on the behavior of information disclosure exists. The indirect mediator effect of perceived benefits on the effect of group buying experience on the behavior of information disclosure exists and the privacy tag has a significant moderating effect on the effect of hot topic interactivity on privacy concerns and the effect of group buying experience on privacy concerns. In this case, all hypotheses were established.

Based on the above illustration, the results obtained are in line with the findings from previous studies regarding privacy and information disclosure in most cases. However, this study is different from previous studies. The innovation lies in selecting privacy antecedents from the perspective of users’ virtual privacy experiences. Considering that there are many types of interaction and online purchasing on social e-commerce platforms, this paper focuses on specific hot topic interactivity and group buying, and explores their impact on privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and the behavior of information disclosure, which contributes to the development of theory and the management practice of enterprises.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

The model applied in this study was established upon previous models. Compared with prior researches, the similarity lies in choosing people’s perceptions of privacy as the antecedents of information disclosure behavior. Privacy concerns served as the key antecedent of behavioral reaction over information disclosure [14]. A large proportion of customers will relinquish some of their personal information for perceived benefits generated from information disclosure if they know that they can obtain benefits [46]. However, this study is still very different from previous researches. The research background of this paper is a relatively new field of social e-commerce, which gives new connotation to information disclosure and privacy. This model extended previous models by connecting the missing links between privacy concerns and perceived benefits among users and privacy antecedents from the perspective of users’ virtual privacy experiences. This model presented a more holistic perspective about information disclosure on social e-commerce platforms.

This research emphasizes factors influencing privacy concerns of consumer information disclosure and the impact of privacy concerns on the behavior of personal information disclosure. The data analysis results also show that two specific factors of privacy antecedents, hot topic interactivity and group buying experience, have significant negative impacts on privacy concerns. Further, privacy concerns have a significant negative impact on the behavior of information disclosure, which can make the APCO model more complete. At the same time, the impact of these two factors on perceived benefits is considered, which is a supplement to the theory of privacy calculus. In addition, this study selects the privacy tag as a moderating variable from the perspective of privacy protection on platforms, which provides a relatively new perspective for subsequent researches on information disclosure and social e-commerce, as well as promotes the development of the above two theories.

These results prove and add new meaning to existing research in the field of information disclosure on social e-commerce platforms. These findings show the relationships between hot topic interactivity, group buying experience, privacy tags, privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and the behavior of information disclosure.

Therefore, hot topic interactivity, group buying experience, and privacy tags are important variables for research on privacy concerns and information disclosure behavior. Ultimately, the developed model can lay a foundation for the potential development of other models across other areas of research.

6.3. Managerial Implications

This study can also help researchers have a better understanding of privacy antecedents, privacy tags, privacy concerns, perceived benefits, and information disclosure of users on social e-commerce platforms. Based on this study, researchers can not only understand these related concepts, but also explore the relationships between them.

Moreover, the results of the current research indicate that enterprises should gradually pay attention to social e-commerce platforms and carry out a series of measures to promote users to disclose personal information, so as to obtain the data needed for operation. First, enterprises should stimulate users’ behaviors of hot topic interactivity on social e-commerce platforms (such as corporations can launch brand-related activities on microblogging to form hot topics), so as to enable users to obtain social support and increase trust in platforms, which can decrease users’ privacy concerns, increase their perceived benefits, and ultimately promote users to disclose personal information. Second, enterprises should promote users’ behaviors of group buying (such as brands can increase the discounts of group buying to attract consumers), so that users can buy the same goods with less money and increase their preference for platforms; this can decrease users’ privacy concerns, increase their perceived benefits, and ultimately increase users’ information disclosure behaviors. Third, enterprises should improve the privacy tag system (such as setting multiple group options) to make users feel that disclosure of information is safe, which can decrease users’ privacy concerns and ultimately promote the disclosure of personal information. In this way, the increase of users’ information disclosure behavior will help enterprises collect more consumers’ information, so as to analyze their preference and trend of marketing, design personalized services, and make better development strategies, which contribute to the long-term operation and sustainable development of enterprises. On the other hand, social e-commerce platforms can gain considerable economic benefits and achieve sustainable development because of the participation of enterprises.

7. Conclusions

There are a few limitations in this study, which provide opportunities for future research. First, many other factors not contained in this model can also influence users’ privacy concerns and information disclosure behavior, therefore, this paper has a certain limitation in selecting independent variables. Second, most of the respondents in this study were young people who often use social e-commerce platforms, which led to an incomplete investigation that ignores the groups of middle-aged and older people. Third, some variables have various dimensions, such as hot topic interactivity and privacy concerns. However, in this paper, their subdivided dimensions are not studied. Thus, the model of this paper could be made more specific through further research.

Author Contributions

Y.S.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation and writing—review and editing; S.F.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing—original draft; Y.H.: supervision and writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Contemporary Business and Trade Research Center, and the Collaborative Innovation Center of Contemporary Business and Trade Circulation System Construction of Zhejiang Gongshang University (16YXYP01).

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the editor Dragana Oborina and several anonymous reviewers giving their valuable suggestions and comments for improving the quality of our paper. We are also very grateful to the Interdisciplinary Innovation Team Building of Internet and Management Change for Promoting the Level of Running Local Colleges and Universities in Zhejiang Province.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement items.

Table A1.

Measurement items.

| Constructs | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Hot topic interactivity | 1. I often answer questions in the area of hot topic. | [65] |

| 2. Other users and I often comment to each other in the area of hot topic. | ||

| 3. Other users and I often click on the “like” button to each other in the area of hot topic. | ||

| Group buying experience | 1. I often take the initiative to open a group to invite others to buy together. | [86] |

| 2. I often participate in groups opened by other people to buy together. | ||

| 3. I buy most products which were on group-buying on a platform at one time. | ||

| Privacy tag | 1. Contents posted on the social e-commerce platform can be set to be visible only to myself. | [87] |

| 2. Contents posted on the social e-commerce platform can be set to be partially visible and I can name groups as privacy tags. | ||

| 3. Contents posted on the social e-commerce platform can be set to not be seen by some people and I can name groups as privacy tags. | ||

| Privacy concern | 1. There would be too much uncertainty associated with giving my personal information to the platform. | [34] |

| 2. There would be a high potential for loss associated with disclosing my personal information to the platform. | ||

| 3. The personal information disclosed on the platform could be likely misused. | ||

| 4. The personal information disclosed on the platform is subject to many threats. | ||

| Perceived benefit | 1. Others’ information disclosure can provide me with the convenience to instantly access the product information that I need. | [48] |

| 2. Information disclosure can provide me with personalized services. | ||

| 3. Information disclosure can provide me with monetary rewards. | ||

| 4. Information disclosure can provide me with entertainment. | ||

| The behavior of information disclosure | 1. I often put the pictures of goods I bought on the platform. | [42] |

| 2. I often put my personal photos on the platform. | ||

| 3. I often add different addresses and cellphone numbers to the platform. | ||

| 4. I often disclose my income situation on the platform. |

References

- Kim, Y.A.; Srivastava, J. Impact of social influence in e-commerce decision making. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Commerce: The Wireless World of Electronic Commerce, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 19–22 August 2007; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007; pp. 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F. The Way of Survival of Social E-commerce. Internet Wkly. 2013, 9, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Spencer, M.K. Exploring the effects of extrinsic motivation on consumer behaviors in social commerce: Revealing consumers’ perceptions of social commerce benefits. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. Internet Business Models and Strategies: Text and Cases; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 242–245. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, E.; King, D.; Lee, J.K.; Liang, T.P.; Turban, D.C. Social Commerce: Foundations, Social Marketing, and Advertising; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 309–365. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.P.; Turban, E. Introduction to the Special Issue Social Commerce: A Research Framework for Social Commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, H.; Ernst, H. Community based innovation: How to integrate members of virtual communities into new product development. Electron. Commer. Res. 2006, 6, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, N.F.; Krishnan, M.S. The personalization privacy paradox: An empirical evaluation of information transparency and the willingness to be profiled online for personalization. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilfoil, D.M.; Jobs, C.G. Mind the gap: A global analysis of the number of buyers to sellers using blogging, social networking, online video, and microblogging platforms. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 5, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Boveda-Lambie, A.M. Advertising versus Invertising: The influence of social media B2C efforts on consumer attitudes and brand relationships. Online Consum. Behav. 2012, 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.B.; Sarkar, S. A Tree-Based Data Perturbation Approach for Privacy-Preserving Data Mining. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2006, 18, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Culnan, M.J.; Armstrong, P.K. Information Privacy Concerns, Procedural Fairness, and Impersonal Trust: An Empirical Investigation; INFORMS: Catonsville, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Weeill, E. Place to Space: Migrating to eBusiness Models; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1097198X.2001.10856309 (accessed on 9 September 2014).

- Smith, H.J.; Dinev, T.; Xu, H. Information privacy research: An interdisciplinary review. MIS Q. 2010, 35, 989–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Empirical studies on online information privacy concerns: Literature review and an integrative framework. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 453–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, F.; Crossler, R.E. Privacy in the digital age: A review of information privacy research in information systems. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 1017–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polites, G.L.; Karahanna, E. The Embeddedness of Information Systems Habits in Organizational and Individual Level Routines: Development and Disruption. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Consumer Responses to the Introduction of Privacy Protection Measures: An Exploratory Research Framework. E-Bus. Appl. Prod. Dev. Compet. Growth Emerg. Technol. 2009, 5, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Teo, H.-H.; Tan, B.C.Y. The Role of Push-Pull Technology in Privacy Calculus: The Case of Location-Based Services. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 26, 135–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Living a private life in public social networks: An exploration of member self-disclosure. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Duong, T.D.; Chen, C.C. Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: A privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginosar, A.; Ariel, Y. An analytical framework for online privacy research: What is missing? Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Ho, Y.; Li, Y.; Turban, E. What Drives Social Commerce: The Role of Social Support and Relationship Quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, P. The Evolution of Social Commerce: The People, Business, Technology, and Information Dimensions. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 31, 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Fan, Z.; Zhu, Q. User-generated content (UGC) concept analysis and research progress. J. Chin. Libr. 2012, 38, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X. Research on the Social e-Commerce Community Based on Interest Mapping. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai University of Engineering and Technology, Shanghai, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D. Research on pricing strategy of social e-commerce platform. J. Southwest Natl. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 39, 800–805. [Google Scholar]

- Tow, N.F.H.; Dell, P.; Venable, J. Understanding information disclosure behaviour in Australian Facebook users. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Hiekkanen, K.; Dhir, A.; Nieminen, M. Impact of privacy, trust and user activity on intentions to share Facebook photos. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2016, 14, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Che, J. Information privacy disclosure on social network sitess: An empirical investigation from social exchange perspective. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2016, 7, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohikamali, M.; Gerhart, N.; Mousavizadeh, M. Location disclosure on LB-SNAs: The role of incentives on sharing behavior. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 71, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sharma, S.K. Learning and self-disclosure behavior on social networking sites: The case of Facebook users. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampong, G.O.A.; Mensah, A.; Adu, A.S.Y.; Addae, J.A.; Omoregie, O.K.; Ofori, K.S. Examining Self-Disclosure on Social Networking Sites: A Flow Theory and Privacy Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Michael, K.; Chen, X. Factors affecting privacy disclosure on social network sites: An integrated model. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, R.S.; Wolfe, M. Privacy as a Concept and a Social Issue: A Multidimensional Developmental Theory. J. Soc. Issues 1977, 33, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, E.F.; Stone, L.D. Privacy in Organizations: Theoretical issues, Research findings, and Protection mechanisms. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1990, 8, 349–411. [Google Scholar]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debatin, B.; Lovejoy, J.P.; Horn, A.-K.; Hughes, B.N. Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes, Behaviors, and Unintended Consequences. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 15, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, T.; Hinsley, A.W.; de Zúñiga, H.G. Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, K.B.; Hoy, M.G. Flaming, Complaining, Abstaining: How Online Users Respond to Privacy Concerns. J. Advert. 1999, 28, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, R.; Acquisti, A. Information revelation and privacy in online social networks. In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, Alexandria, VA, USA, 7 November 2005; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Koohikamali, M.; Peak, D.A.; Prybutok, V.R. Beyond self-disclosure: Disclosure of information about others in social network sites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G.; Zahedi, F.M.; Gefen, D. Do context and personality matter? Trust and privacy concerns in disclosing private information online. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, K. The influence of information sensitivity compensation on privacy concern and behavioral intention. ACM SIGMIS Database 2009, 40, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, J.; Nowak, G.; Ferrell, E. Privacy Concerns and Consumer Willingness to Provide Personal Information. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Im, S.; Taylor, C.R. Voluntary self-disclosure of information on the Internet: A multimethod study of the motivations and consequences of disclosing information on blogs. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 25, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, S.; Graeff, T.R. Collecting and using personal data: Consumers’ awareness and concerns. J. Consum. Mark. 2002, 19, 302–318. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Luo, X.; Carroll, J.M.; Rosson, M.B. The personalization privacy paradox: An exploratory study of decision making process for location-aware marketing. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 51, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.R.; Gordon, M.E. Direct Mail Privacy-Efficiency Trade-offs within an Implied Social Contract Framework. J. Public Policy Mark. 1993, 12, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Marcus, J. Students’ self-presentation on Facebook: An examination of personality and self-construal factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatolas, L.N.; Welzer, T.; Hericˇko, M.; Hölbl, M. Privacy antecedents for SNS self-disclosure: The case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, S.J. Exploring Models of Interactivity from Multiple Research Traditions: Users, Documents, and Systems. In Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs; Lievrouw, L.A., Livingstone, S., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2002; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, J.R.; Thorson, E. The Effects of Progressive Levels of Interactivity and Vividness in Web Marketing Sites. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y. Examining mobile instant messaging user loyalty from the perspectives of network externalities and flow experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, R.J.; Lai, H.; Lin, H.C. Consumer adoption of group-buying auctions: An experimental study. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 11, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, R.J.; Wang, B. Bid together, buy together: On the efficacy of group-buying business models in Internet-based selling. In Handbook of Electronic Commerce in Business and Society; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.T.; Brock, J.L.; Shi, G.C.; Chu, R.; Tseng, T.H. Perceived benefits, perceived risk, and trust. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2013, 25, 225–248. [Google Scholar]