Open Innovation Strategies for Sustainable Urban Living

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Concept of Open Innovation

2. Research Context and Method

2.1. Sustainable Urban Living as a City Vision

2.2. Method

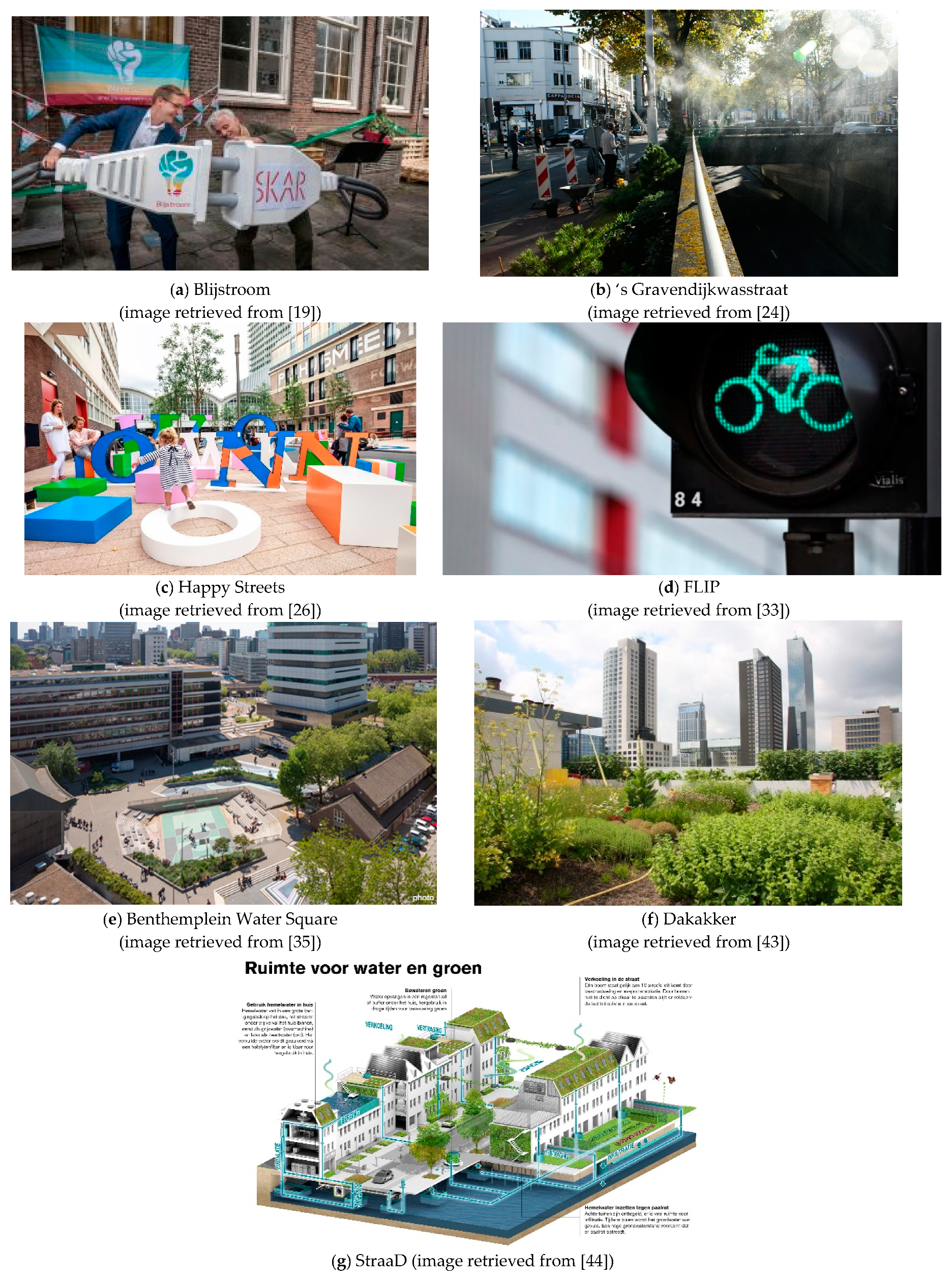

3. Initiatives Aiming for Sustainability and/or Liveability in Rotterdam

3.1. Blijstroom: Cooperative for Shared Solar Panel Energy

3.2. ‘s Gravendijkwasstraat

3.3. Happy Streets

3.4. FLIP: Traffic Light Interventions

3.5. Benthemplein Water Square

3.6. DakAkker: Rooftop Urban Farm

3.7. StraaD (Water-Sensitive Rotterdam)

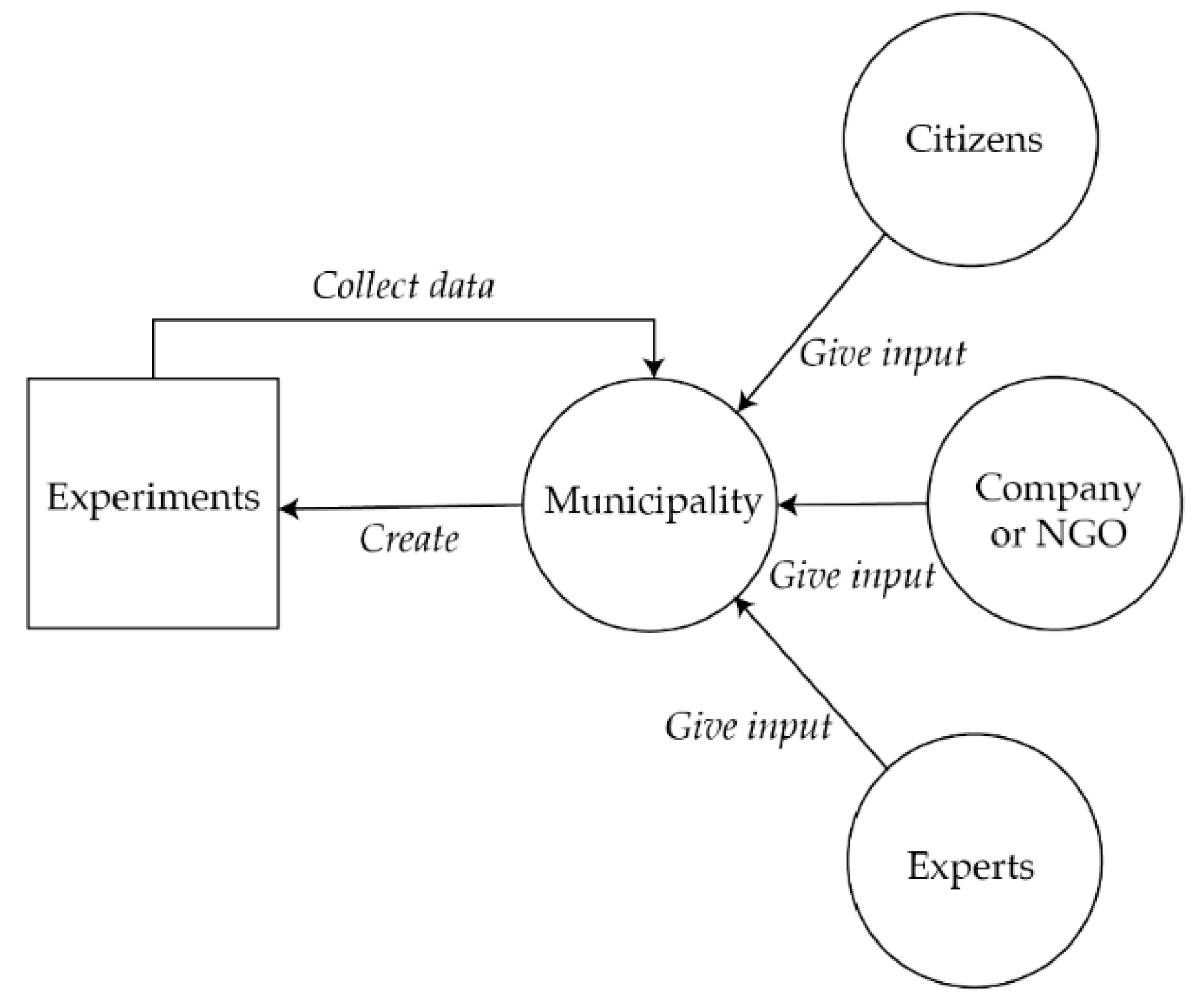

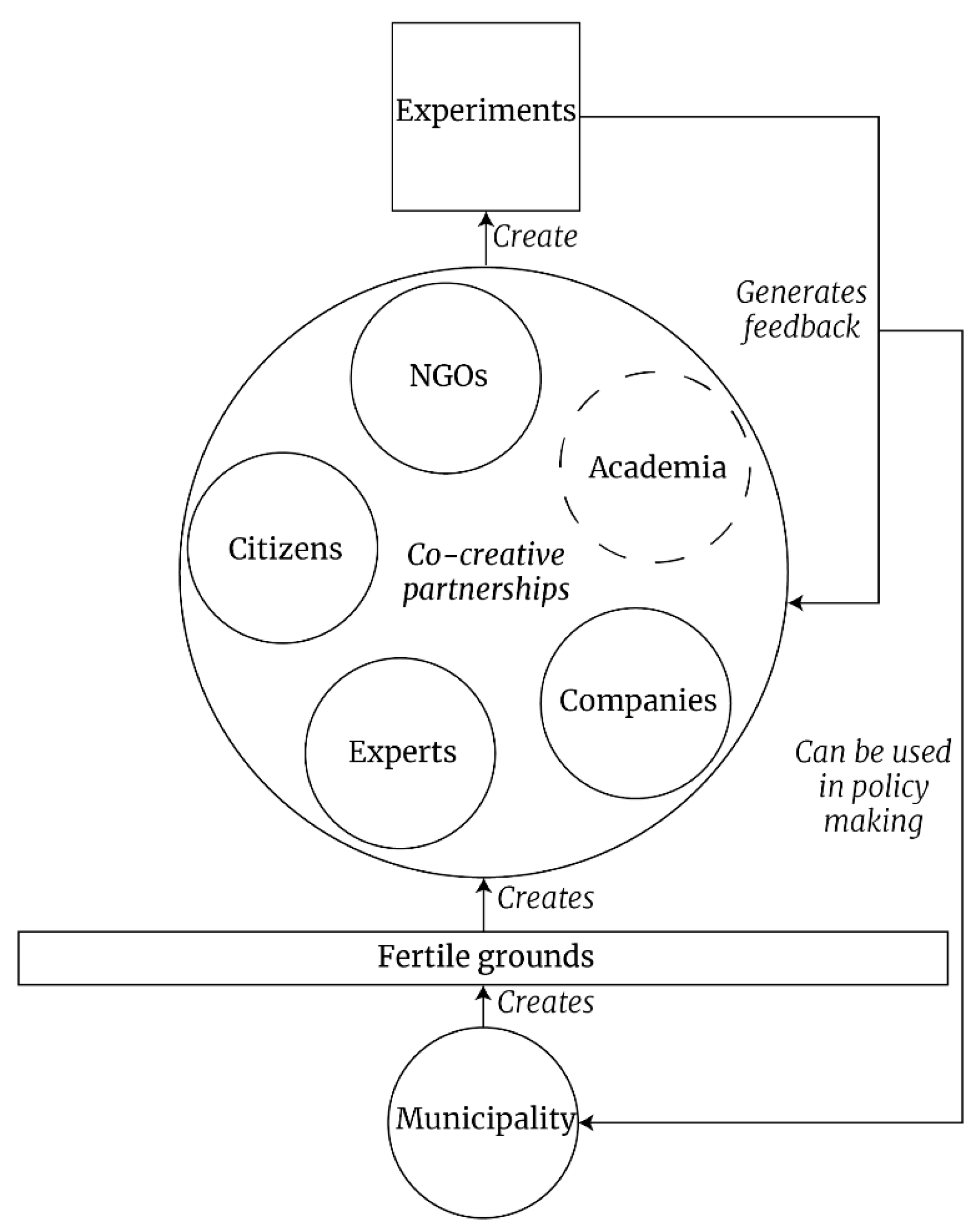

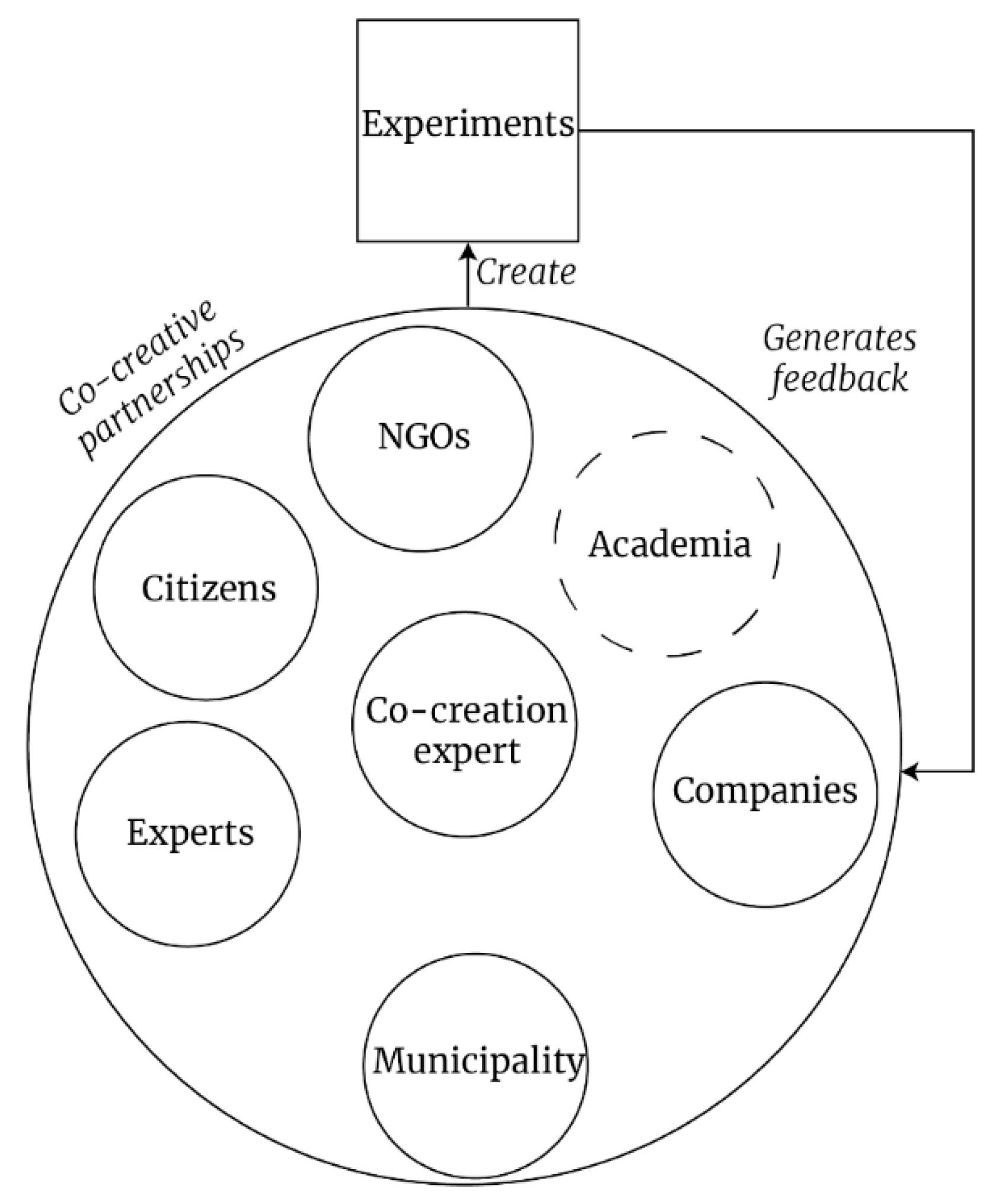

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulder, I. Sociable smart cities: Rethinking our future through co-creative partnerships. In Distributed, Ambient, and Pervasive Interactions. DAPI 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Streitz, N., Markopoulos, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8530, ISBN 978-3-319-07788-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommert, B. Collaborative innovation in the public sector. Int. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 11, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Hwang, T.; Choi, D. Open innovation in the public sector of leading countries. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, E.; Lee, M.; Majchrzak, A. Open innovation requires integrated competition-community ecosystems: Lessons learned from civic open innovation. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, C.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D.; Steenbergen, F.; van Wittmayer, J. Transition Management in Urban Context—Guidance Manual, Collaborative Evaluation Version; Drift, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Solecki, W.; Hammer, S.A.; Mehrotra, S. Cities lead the way in climate-change action. Nature 2010, 467, 909–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, K.; Gunnarsson-Östling, U. Climate change scenarios and citizen-participation: Mitigation and adaptation perspectives in constructing sustainable futures. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, D.L.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Grove, J.M.; Marshall, V.; McGrath, B.; Pickett, S.T.A. An Ecology for Cities: A Transformational Nexus of Design and Ecology to Advance Climate Change Resilience and Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3774–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concilio, G.; Tosoni, I. Introduction. In Innovation Capacity and the City; Concilio, G., Tosoni, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-3-030-00123-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castan Broto, V. Urban Governance and the Politics of Climate Change. World Dev. 2017, 93, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open innovation: A new paradigm for Understanding Industrial Innovation. In Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm, 1st ed.; Chebrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 1–12. ISBN 0199290725. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgers, D.; Ihl, C. Citizensourcing: Applying the Concept of Open Innovation to the Public Sector. Int. J. Public Particip. 2010, 4, 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Puerari, E.; de Koning, J.; von Wirth, T.; Karré, P.M.; Mulder, I.J.; Loorbach, D.A. Co-creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D. Steering transformations under climate change: Capacities for transformative climate governance and the case of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 19, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romein, A.; Trip, J.J. Key elements of creative city development: An assessment of local policies in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. In Proceedings of the City Futures ‘09, Madrid, Spain, 4–6 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, S. Feasibility Study on Making Van Maanenblok a Near Zero Energy Building Urban Neighbourhood. Master’s Thesis, KTH, Stockholm, Sweden, August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwe Business Modellen. Available online: http://nieuwebusinessmodellen.nl/map/thema/duurzaamheid/blijstroom/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Blijstroom. Available online: https://blijstroom.nl/ (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Qurrent. Available online: https://community.qurrent.nl/zonne-energie-en-zonnepanelen-4/blijstroom-3263 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Blijstroom. Available online: https://citylab010.nl/initiatieven/archief/blijstroom (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Transformism. Available online: http://www.transformism.org/posts/view/55 (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- ‘s Gravendijkwasstraat. Available online: https://www.citylab010.nl/plannen/sgravendijkwasstraat (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Stadslab Luchtkwaliteit. Available online: https://www.stadslabluchtkwaliteit.nl/ (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- RTV Rijnmond. Available online: https://www.rijnmond.nl/nieuws/149916/Bewoners-s-Gravendijkwal-razend-over-opknappen-Coolsingel (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Happy Streets. Available online: http://happystreets.nl/over/ (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Drift. Available online: https://drift.eur.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Nieuwe_wegen_inslaan_mobiliteitsarenaRdam.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Parking Day. Available online: http://happystreets.nl/parking-day/ (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Dutch News. Available online: https://www.dutchnews.nl/features/2018/03/meet-happy-streets-rotterdams-cheeky-activists-for-social-mobility-in-the-city/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Pattianakotta, J. Duurzame Mobiliteit Als Doel of Middel. Bachelor’s Thesis, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bruntlett, M.; Bruntlett, C. Streets Aren’t Set in Stone. In Building the Cycling City; Bruntlett, M., Bruntlett, C., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 7–26. ISBN 978-1-61091-880-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gezondere Lucht. Available online: https://gezonderelucht.nl/actueel/flips-helpen-fietsers-sneller-oversteken (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Fietsfan 010. Available online: http://fietsfan010.nl/uitgelicht/warmtesensor-%EF%BB%BFgeeft-fietsers-meer-groen/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Fietsplan Rotterdam. Available online: https://www.rotterdam.nl/wonen-leven/fietsplan/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- De Urbanisten (Waterplein Benthemplein). Available online: http://www.urbanisten.nl/wp/?portfolio=waterplein-benthemplein (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Benthemplein Water Square: An Innovative Way to Prevent Urban Flooding in Rotterdam. Available online: https://www.c40.org/case_studies/benthemplein-water-square-an-innovative-way-to-prevent-urban-flooding-in-rotterdam (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Diaz, P.; Yeh, D. Adaptation to climate change for water utilities. In Water Reclamation and Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressers, N. The impact of collaboration on innovative projects: A study of Dutch water management. In Public Innovation through Collaboration and Design, 1st ed.; Ansell, C., Torfing, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 107–123. ISBN 9781134452859. [Google Scholar]

- Bressers, N.; Edelenbos, J. Planning for adaptivity: Facing complexity in innovative urban water squares. Emerg. Complex. Organ. 2014, 16, 77–99. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1681098795?accountid=27026 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Errigo, M. The Adapting city. Resilience through water design in Rotterdam. TeMa—J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2018, 11, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Urbanisten (Climate Proof Zomerhofkwartier). Available online: http://www.urbanisten.nl/wp/?portfolio=climate-proof-zomerhofkwartier (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Resilient Rotterdam. Available online: https://www.resilientrotterdam.nl/en/initiatieven/green-roof-harvests-1 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- De Luchtsingel. Available online: https://www.luchtsingel.org/en/locaties/roofgarden/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- De straaD. Available online: http://www.destraad.nl (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Water Sensitive Rotterdam. Available online: https://www.watersensitiverotterdam.nl/plekken/de-straad/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Bosch Schlabbers. Available online: https://www.boschslabbers.nl/nl/project/straad/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Mulder, I. Co-creative partnerships as catalysts for social change. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2018, 11, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Calulier-Grice, J.; Geoff, M. The Open Book of Social Innovation; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 987-1-84875-071-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, I.; Kun, P. Hacking, Making, and Prototyping for Social Change. In The Hackable City; de Lange, M., de Waal, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 225–238. ISBN 978-981-13-2694-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojasalo, J.; Tähtinen, L. Integrating open innovation platforms in public sector decision making: Empirical results from smart city research. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2016, 6, 38–48. Available online: http://timreview.ca/article/1040 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

| Air Quality | CO2 Reductions | Flood Management | Liveability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blijstroom | X | |||

| ‘s Gravendijk wasstraat | X | X | ||

| Happy streets | X | X | X | |

| FLIP | X | X | X | |

| Benthemplein water square | X | X | ||

| DakAkker | X | X | X | |

| StraaD | X | X | X |

| Municipality | Citizens | Agency for Design or Architecture | Industry | Academia | Other * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blijstroom | Funding | Initiator + Execution | Execution + Knowledge | |||

| ‘s Gravendijk wasstraat | Funding | Initiator + Knowledge + Execution | Initiator + Knowledge + Execution | Knowledge + Execution | ||

| Happy streets | Initiator + Funding | Knowledge + Execution | Initiator + Knowledge + Execution | Initiator + Knowledge | ||

| FLIP | Initiator + Funding + Knowledge + Execution | Knowledge | Knowledge | |||

| Benthemplein water square | Initiator + Funding | Knowledge | Initiator + Knowledge | Knowledge | Funding | |

| DakAkker | Funding | Execution | Initiator + Knowledge | Funding + Knowledge | Knowledge + Execution + Funding | |

| StraaD | Funding + Knowledge | Initiator + Knowledge + Execution | Knowledge + Execution | Knowledge | Knowledge + Funding |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Genuchten, E.; Calderón González, A.; Mulder, I. Open Innovation Strategies for Sustainable Urban Living. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123310

van Genuchten E, Calderón González A, Mulder I. Open Innovation Strategies for Sustainable Urban Living. Sustainability. 2019; 11(12):3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123310

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Genuchten, Eva, Alicia Calderón González, and Ingrid Mulder. 2019. "Open Innovation Strategies for Sustainable Urban Living" Sustainability 11, no. 12: 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123310

APA Stylevan Genuchten, E., Calderón González, A., & Mulder, I. (2019). Open Innovation Strategies for Sustainable Urban Living. Sustainability, 11(12), 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123310