Abstract

This study makes a significant contribution towards theory and knowledge of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) within the social sustainability discourse. The study focused on investigating if SMEs in developing economies directly benefit from practising social sustainability through examining the relationship between social sustainability and financial performance, customer satisfaction as well as employee satisfaction. A total of 238 SMEs from the Limpopo province of South Africa were surveyed through a self-administered questionnaire at the hand of convenience sampling technique. The hypotheses in the study were assessed through structural equation modelling (SEM) through AMOS software version 25. The study results revealed that all three postulated hypotheses were supported. Thus, social sustainability was found to be positively and significantly associated with financial performance, customer satisfaction performance as well as employee satisfaction performance. The findings in this study indicate that by practising social sustainability, SMEs potentially benefit on a broader performance spectrum.

1. Introduction

Within the spectrum of sustainable development, there are mixed notions pertaining to what constitutes the contribution of SMEs in the prevailing sustainable development dimensions, namely, economic, ecological and social [1]. Consideration towards small medium enterprises’ (SMEs) general contribution toward the economies of the world has grown immensely in literature and research domains [2]. The progressive contribution that SMEs make in the global economy is irrefutable and is enshrined in economic growth, poverty alleviation and job creation strategies pursued by many economies both in the developed and developing world. For that matter, the essence of SMEs tied with the upsurge of sustainability especially for the developing world means SMEs’ research is vital for economic growth in the contemporary world [3]. Thus, the management and flourishing of SMEs should seldom be approached in an unsystematic and disaggregated approach. SMEs strategically contribute toward economic progression and wealth making predominantly in traditionally deprived populations [4] and are considered as the mainstay of most African nations [5]. Alternatively, SMEs stand as “the future” for many developing nations. Thus, their role in sustainable development is of much research interest.

However, SMEs possess certain specificities and typical characteristics in terms of capabilities and resources that differ from large corporations. This makes the application and utilisation of large corporations’ strategies challenging, if not impossible. Particularly, considering that SMEs are prone to a myriad of challenges which are seldom experienced by large firms. For instance, globalisation and competition increase the number of competitors that native SMEs must deal with. According to Wang and Shi [6], globalisation has heightened the extent of competition more than ever before as governments are increasingly doing away with the traditional barriers on their borders that protected local small businesses. In South Africa, the challenges for SMEs, tend to vary with location, thus, it is crucial to note that all domestic SMEs seldom face similar challenges [7].

The general premise which has driven firms to adopt sustainable development is that by practising sustainability a business stands to benefit widely [8,9]. On the other hand, pressure has presently increased for business to drastically shift from sustainability strategies in the boardroom to implementation and follow-ups of these strategies [9]. However, one of the least debated areas in today’s research concerns the social sustainability role of SMEs in the sustainable development spectrum and the subsequent impact on SMEs. The question arises pertaining to understanding the nature of social sustainability practices within the small businesses spectrum in the developing world. Latent literature acknowledges the contribution made by SMEs towards social sustainability in creating employment particularly for the neglected categories of the society [10] within developing nations. Some authors have termed sustainable development, planet, people and profits. Accordingly, these activities of SMEs towards the development of people are positively related to the quests of socially sustainable development.

As outlined by Sy [9] social sustainability pertains to the extent to which a firm translates its social responsibility goals into reality. There is a need to ascertain the relationship between this translation of social responsibility goals into reality with the performance of SMEs. The relationship between SMEs’ participation in social sustainability and the subsequent impact on firm performance is still unsatisfactorily researched and documented in latent literature. Social sustainability is critical for firms regardless of whether they are huge or small because businesses highly depend on the health, steadiness and affluence of their respective societies [3,8]. Henceforth, the aim of this study is to determine if there is an impact on the firm of translation of social sustainability into practices and in the context of SMEs within the developing economies milieu. Empirically, the study utilises SMEs located in the South African province of Limpopo which is predominantly rural. Preceding the first section in this study, the introduction, a literature review of SMEs in Africa as well as the concepts of social sustainability and firm performance is provided. Next, the research methodology, data analysis, results and then conclusions are provided in this paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining SMEs in Africa

The definition of SMEs varies across Africa and a few African countries were randomly selected and discussed herein. Firstly, in Tanzania SMEs were found in three different categories. The definition utilises the two quantitative criteria, namely, the number of employees and capital invested in differentiating SMEs. The first category of SMEs in the Tanzanian context constitute of micro-enterprises which employ up to five employees. As for the capital invested, micro enterprises need to have 5 million Tanzanian shillings (TZS) invested in machinery. Secondly, small enterprises should have five to 50 employees and TZS 5 to 2000 million. Finally, medium-sized enterprises ought to have 50 to 100 employees and TZS of 200 to 800 million [11].

In Ghana, various definitions have been propounded with regards to small-scale enterprises but the most prominently utilised method is the number of workers in a firm. One of the official sources, the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) regards enterprises with less than 10 workers as small-scale firms and those with more than 10 workers as medium and large-sized firms [12]. On the other hand, the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI) of Ghana utilises a two-pronged approach to define SMEs. The NBSSI utilises fixed assets and the number of workers in its definition. Accordingly, the NBSSI defines a small-scale firm as a business with less than nine employees, and has plant and machinery (disregarding land, buildings and vehicles) that are below 10 million Ghanaian cedes [12].

However, the continuous depreciation of the local currency has been regarded as posing definitional challenges when the value of assets is utilised. As such, Asamoah [5] argues that the most used definition is the one given by the EU which utilises the headcount of employees and turnover. In this regards, the US dollar (US$) is used instead of the Ghanaian cedes. Based on this criterion, a small-scale firm is defined as employing more than five workers and not exceeding 50 workers. The value of assets, disregarding land, building and working capital-should be less than $US 30,000 and the annual income turnover should be between $US 6000 and $US 30,000. On the other hand, a medium-sized firm is deemed to be a business employing between 50 and 100 employees.

In Nigeria, still, the definition of SMEs differs. According to Apulu, Latha and Moreton [13], the Small and Medium Sized Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN) categorises SMEs into micro, small and medium sized enterprises. SMEDAN states that a micro firm is an enterprise constituting fewer than ten employees with an annual turnover that is less than five million Naira. Furthermore, SMEDAN details that a small firm is a business employing 10–49 workers with an annual turnover ranging between five to 49 million Naira. Finally, the SMEDAN regards an enterprise as a medium firm if it employees between 50–199 workers whilst the annual turnover of 50–499 million Naira.

In South Africa, the Department of Trade and Industry [14], defines small medium micro enterprise (SMMEs) in South Africa as any business that is having less than two hundred employees or no more than five hundred employees, and the annual turnover of less than five million rands, capital assets or equipment of less than two million rands and the owner is directly committed to management of the business. As such, in this study, both the quantitative and qualitative criteria are utilised from the South African perspective. This definition ignores the variances that apply in terms of the variances in industry as outlined in the definition contained in the National Small Business Act of South Africa 1996 as amended in 2003 [14]. Many of the SMMEs in South Africa eventually take place in rural areas, whereby they operate on small premises and as time goes on they move to large premises that are sustainable for their business [15].

2.2. Social Sustainability

Social sustainability transpires when prescribed and informal procedures, structures, associations and interactions vigorously enhance the capability of contemporary and upcoming generations to generate healthy and liveable societies. The social dimension or social equity principle under sustainable development relates to all societal members having equal access to the available resources and opportunities [16]. Thus, social sustainability refers to activities that ensure that communities are impartial, varied, allied and self-governing and deliver a noble value of life. Acute to the delineation of sustainable development is the recognition that “needs” contemporaneous and impending ought to be achieved in an even-handed setting [17]. Bogt [18] argues that a firm may regard it socially sensible to imitate other firms, that is, to adopt socially rational behaviours in order to achieve this desired equilibrium.

Social activities focus on the community, sports, health and well-being, education, helping the low-income earners as well as participating in the community [19]. These activities are regarded as interventions towards the enhancement of social and cultural causes in the societies as well as community development [19]. SMEs have been considered crucial to the support of community activities in the European as well as Latin American economies. Accordingly, an empirical study by Polášek [20] established that societal activities such as donations in the form of finance and kind, volunteering, education to the society, assistance towards the societal standards of living (i.e., sports, culture, etc.) as well as partnering with local schools, authorities and different community organisations are vital for SMEs.

On the other hand, Thiel [21] indicates that there are four themes that define the social domain in a sustainability context, namely, social-economics, stakeholders, societal-wellbeing and social sustainability. Consistently, social sustainability includes definitions of society, community and culture and is measured in the firm’s performance in donations, safety, strategic philanthropy and corporate citizenship [22]. Thus, social sustainability places a demand upon firms to play an active role and acknowledge more responsibilities toward stakeholders and the social environment they operate in [23]. Human needs include basic needs such as food, shelter, clothing as well as good quality of life, with quality of life including things like healthcare, education and political freedom [21]. Overall, social sustainability is measured through principles, actions and measures implemented [9].

The firm’s appearance in the locality of its operations, the way in which it is regarded as an employer, service provider and accomplice in the local confinements categorically influence its competitive locus [20]. Moreover, businesses that are held as a socially dynamic stand to experience an enhancement in their repute from the community and business guild. In this instance, this heightens the prospects for businesses to draw capital together with improving their competitive situation [19]. SMEs are conspicuous in availing social sustenance in the areas of sporting activities in nearly all the nations in Europe. Coherently, in Latin America, SMEs appear to be vastly dynamic in the fields of sporting, healthiness and cultural happenings [19]. In Africa, among others, SMEs contribute towards social sustainability through employing people with inadequate education and skills levels, women in the lower spectrums of the society. According to Apulu et al. [13], SMEs support in enhancing the living standards of people through bringing about extensive local capital formation and attaining great levels of productivity and capacity.

2.3. Firm Performance

Firm performance constitutes the second construct in this study. Firm performance is not a new concept in the field of business research [24]. However, despite its prominence in latent literature, the construct of firm performance is challenged by incongruences pertaining to indicators being selected based on the researcher’s convenience [25]. Another incongruence noted by Santos and Brito [25] is that of inadequate consideration of the dimensionality of firm performance. Thus, firm performance means different things to different people. According to Ha-Brookshire [26] firm performance is a complex concept to define and the complexity of the definition is even more entrenched within the context of SMEs operations. Consistently, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez et al. [24] argue that a vast difference found in firms is the main reason why the definition of business performance is challenging. Thus, there is a need to consider how firm performance can be assessed within the context of SMEs which have substantive differences contrasted with large businesses [8].

This study utilises both financial and non-financial measures of ascertaining the impact of social sustainability on SMEs. Financial measures have long proven to be reliable when it comes to ascertaining the outcomes of strategies and decisions by businesses [27]. However, universal application of financial measures in ascertaining business performance has since been subject to debate with assertions promulgated that financial measures alone are not sufficient to measure the intangible aspects of business such as social sustainability [28]. For adequacy of measurement, there is a need to augment financial measures with non-financial measures so as to properly depict the outcome of business activities that are undertaken by firms. To this end, the stakeholder approach has been utilised in an endeavour to encapsulate the effects of business activities on different contracts it has with various interested parties. Whilst, financial performance is primarily concerned with the shareholders or owners of the business, there is a need to also ascertain the performance of firms with regards to other interested parties such as customers, employees, society and suppliers [28,29]. In this regards, this study focuses on the three primary stakeholder groups, namely, shareholders, customers and employees. As indicated in latent literature [30], sustainability practices by businesses should be designed in a stakeholder-inclusive manner and respond to numerous demands by different stakeholders. In addition, firms (large and small) need to proactively communicate their sustainability strategies and outcomes so as to enhance their relationships with their respective stakeholder groups [30].

Consistently, latent research indicators have utilised either economic (profitability and productivity measures) financial or growth indicators [24]. Furthermore, within the sustainability spectrum, it is argued that there is a need to broaden the matrices utilised to measure firm performance [8,25]. On the other hand, Santos and Brito [25] consider multidimensionality to consist of financial performance and non-financial performance, with the financial performance dimension comprising profitability, growth and market value. Selvarajan, Ramamoorthy, Flood, Guthrie, MacCurtain and Liu [31] state that return on investment (ROI), earnings per share and net income after tax have often been employed as measures of financial performance. Profitability and growth indices are of high significance in characterising firms between more and less successful ones [32]. However, the financial measurement of firm performance faces criticism because it is primarily backwards-looking and it also partially predicts the future pertaining to depreciation and amortization [33]. In this regard, the following hypothesis was postulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a significant positive link between social sustainability practices (SSD) and financial performance (FFP) of SMEs in Limpopo Province.

Financial measures are ex-post and focus on recognised strategies whilst they disregard the future [34]. Consistently, the phenomenon of definitional confusion with regards to firm performance emanates from authors utilising antecedents of performance as indicators of performance [25]. Thus, Sambharya [34] critiques that financial measures also tend to be internally oriented and assess management, whilst they disregard the stakeholders and external environments. Furthermore, Al-Matari et al. [33] propound that financial performance is regarded to be insufficient as a firm performance measure because it is subject to the accounting profession standards. Thus, it is constrained by the accounting practice since it is determined by the accountant. Alternatively, non-financial performance dimensions that have been utilised by authors include innovativeness, employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, entrepreneur satisfaction and competitiveness [26,35,36]. Whereas, Santos and Brito [25] note that the non-financial dimensions are measured at the hand of competitive issues such as customer satisfaction, quality, innovation, employee satisfaction and reputation. Furthermore, research on sustainable performance, in general, has been observed to be insufficient from the milieus of developing countries, especially from a subjective perspective [37]. On this background, the following hypotheses were developed in this study.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a significant positive link between social sustainability practices (SSD) and customer satisfaction performance (CFP) of SMEs in Limpopo Province.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There is a significant and positive link between social sustainability practices (SSD) and employee satisfaction performance (EFP) of SMEs in Limpopo Province.

3. Research Methodology

This research area in this study was the Limpopo Province of South Africa. Limpopo province is predominantly sustained by small businesses with a fairly small number of big businesses that have been established in the province. The target population for this study was SMEs in general that were operating in the Limpopo province. This is alluded to by the fact that Limpopo is primarily rural with the majority (71%) of its population being located in rural areas [38]. Limpopo has been identified as the fastest growing economy and this is parallel also to SME growth rate which has been noted as the highest at 34% [39]. As such, the province was reckoned appropriate to provide information pertaining to the behaviour of SMEs as pertains to sustainable development practices. Surveys can be categorised into two broad classes, namely, the questionnaire and the interview [40].

The quantitative research approach was utilised for the study at hand. For sampling, the convenience technique was selected due to the inherent accessibility, proximity of respondents and costs advantages. A cross-sectional method using a self-administered questionnaire in the form of a standardised measuring instrument was used (See Appendix A). Self-administered questionnaires can either be printed or electronic [41]. Paper questionnaires can be distributed through the mail, in-person drop-off, inserts or through fax. Electronically, self-administered questionnaires can be completed through e-mails, internet website, interactive kiosks, or through mobile phones. This study utilised both printed in-person drop off and electronic mail (e-mail) as in distributing the questionnaire.

All in all, 500 questionnaires were dispersed in the survey and 254 were returned which represents a 50.8% response rate. A further 16 were not usable due to partial responses, and 238 questionnaires were subsequently utilised giving an effective final survey response rate of 47.6%. The self-administered questionnaire was designed as well as operationalised following a thorough literature review and constituted a 5-point Likert scale type of questions. Social sustainability items (See Appendix A) used in the study were primarily adopted from a study by Høgevold et al. [22]. The psychometric measurements in the scales that were utilised were reckoned to be fitting as they exceeded the threshold of 0.6 with Cronbach’s alpha statistics of between 0.66 and 0.68 values. For firm performance, the questionnaire items (see Appendix A) were operationalised based on previous works [25,31,33,34]. The obtained data were analysed in two ways, namely, descriptive and inferential analyses. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 25 and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS Version 25.0) were used as analytical software.

Furthermore, Amos was specifically used to perform hypothesis testing under inferential analysis, through structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM comprises a measurement model and a structural model. The measurement model pertains to the relationship between the latent (endogenous and exogenous) constructs and their relative observation variables, while the structure model relates to the correlation between latent constructs, exclusively [42]. In SEM, a researcher can utilise three approaches, namely, confirmatory approach, alternative model approach and model generation approach. Herein, this study utilised the confirmatory approach whereby the aim was to establish whether the data would fit the model based on a literature review [43].

4. Results

Maiden analyses pertaining to screening for missing data, outliers, and normality (kurtosis and skewness) revealed that no significant inconsistencies in the data were identified. Table 1 presents information on the respondents’ demographic attributes as well as the surveyed firms’ characteristics. Herein, most of the respondents were males (59.7%), aged 31 to 40 years (36.1%), and owners (57.1%). Additionally, the firms surveyed mostly employed 6–20 employees (40.3%) and were urban-based (77.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic details and business profile.

Furthermore, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed through principal component analysis (PCA) and varimax rotation to determine the dimensionality of factors contained in the study. Data was regarded to be orthogonal; as such the Varimax rotation option was used in this study. Orthogonal rotation is utilised when factors are deemed to be uncorrelated and make use of a 90° rotation of factors from each other [44,45]. Of the three prominent orthogonal rotation techniques, namely, quartimax, varimax and equimax, varimax was preferred because it reduces the number of variables that contain high loadings on each given factor and aims to ensure that small loadings are even more minimised [45]. Before EFA, data were initially examined for sample adequacy through Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS) tests, of which all the items had KMO values above 0.5 and BTS was significant (p < 0.5) implying suitability of data for factor analysis [46] (see Table 2). EFA results on factor loadings are shown in Table 3 with all items showing considerably high loadings exceeding the threshold of 0.50 [44].

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite reliability (CR) and R-squared.

4.1. Measurement Model

Data were analysed for convergence through Cronbach’s coefficient alpha (α) scores and all the values exceeded the threshold of 0.7 signifying significant convergence. Information presented in Table 3 shows Cronbach’s coefficient values ranging between 0.893 and 0.934 which specify significant reliability. Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were utilised to ascertain internal consistency in the study. CR and AVE determine the extent of variance captured by a construct’s measure in contrast to the measurement error [47]. The Fornell and Lacker [47] approach was utilised to in the computation of the CR and AVE values whereby parameter estimates and their relative t-values for each construct where utilised. CR values exceeding 0.7 and AVE values greater than 0.5 are as viewed satisfactory for internal consistency [48]. As shown in Table 3, all the CR and AVE values exceed the postulated cut-off values depicting internal consistency.

Correlation coefficients of constructs (CCC) and the square root of average variance extracted (square root of AVE) were applied for the purposes of discriminant validity ascertainment. Herein, Table 4 reflects that most of the correlation coefficients of constructs were lower than the specified 0.80. Per se, discriminant validity is explained by the low correlation between constructs which represent uniqueness or distinctiveness of theoretical operationalisations [40,41,45]. The square roots of AVE values for each construct are in the bold and diagonal (see Table 4). Respectively, all the square root of AVEs exceed their respective correlation coefficients thereby positing satisfactory discriminant validity [47].

Table 4.

Correlation matrix and Square roots of AVEs.

Furthermore, a measurement model was formulated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA concentrates on determining the extent to which the manifest variables satisfactorily measure the latent variables as well as ascertaining matters of validity and reliability [49]. CFA depicted acceptable fit (chi-square = 318.530, df = 86, p = 0.000, N = 238, confirmatory fit index (CFI) = 0.963, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.946, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.096, SRMR = 0.0462, and the chi-square/df = 3.704). Thus, all the fitness statistics were acceptable apart from the chi-square statistic which is required to be insignificant and is seldom so in huge sample sizes because of its sensitivity to sample sizes above 200. However, in order to achieve acceptable fitness, an item (CSP1) pertaining to customer satisfaction performance construct was dropped due to high residuals of 2.987 and 2.886 which exceeded the acclaimed threshold of within +/−2.58 values [50].

4.2. Structural Equation Modelling

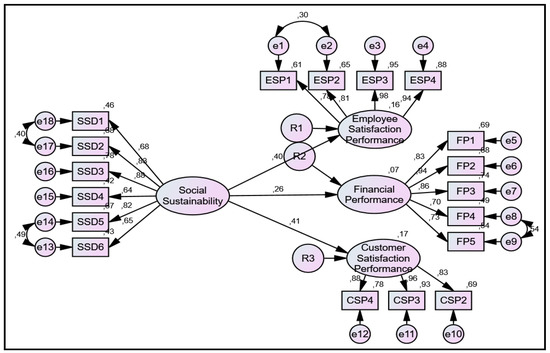

In order to examine the hypothesised relationships pertaining to social sustainability practices and financial performance, customer satisfaction performance as well as employee satisfaction performance, a path analysis approach in structural equation modelling (SEM) was done. SEM is also called covariance structure analysis, covariance structural modelling, or analysis of covariance structures, as well as causal modelling. SEM is a family of superior analytical techniques that are highly efficient because it evaluates a series of dependence and interdependence relationships [51,52]. The SEM technique is regarded as a second-generation multivariate method that integrates multiple regressions and confirmatory analysis to predict simultaneously various interrelationships amongst the constructs of the hypothesised model [52]. Thus, through AMOS version 25, the SEM approach was utilised because it is advantageous when it comes to simultaneous estimation of parameters in a single model. Model fitness was deemed satisfactory despite of a significant chi-square (chi-square = 553.896, df = 196, p = 0.000, N = 238, CFI = 0.910, TLI = 0.897, chi-square/df = 2.826, RMSEA = 0.086). In the research, R-squared (R2) values pertaining to the endogenous latent variables, explicitly, financial performance (7%), customer satisfaction (17%) and employee satisfaction performance (16%) indicate the magnitude of predictive ability of the model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural model.

Table 5 is a presentation of the results of path analysis through the structural model and Figure 1 diagrammatically illustrates the model. Standardised regression weights were used to conduct a path analysis and the results supported H1, meaning that there is a significant positive bond between social sustainability practices and financial performance (β = 0.263, t = 3.484, p < 0.001). The results also exposed a significant positive association between social sustainability practices and customer satisfaction performance (β = 0.410, t = 5.289, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Lastly, pertaining to H3, a significant positive relationship between social sustainability practices and employee satisfaction performance (β = 0.397, t = 5.135, p < 0.001), was also established.

Table 5.

Results of hypotheses testing.

5. Conclusions

The study presented social sustainability as a major driver of SMEs performance in developing in economies, with a case of South Africa being utilised. The impact of social sustainability in this context was determined by considering three aspects of firm performance, namely, financial, customer satisfaction and employee satisfaction performance. In other words, the study endeavoured to integrate the broader impact of social sustainability by considering the perspectives of employees, customers as well as the firm. This approach is consistent with latent literature [10] in the social sustainability context as it provides a fairer understanding of the contribution of social sustainability towards the firm by assessing the major social stakeholders. From the results of path analysis, social sustainability was significantly linked to financial performance, customer satisfaction performance, and employee satisfaction performance, respectively.

Firstly, social sustainability was found to be significantly and positively related to financial performance. In consistency with past studies [53], the results of this study suggest that the SME owner/managers perceived that an increase in social sustainability practices potentially enhanced the financial performance of their small firms. Thus, with traditional aspects of firm performance, namely, financial performance, SMEs should expect readjustment of business performance due to social sustainability. Secondly, a positive and significant association was also established between social sustainability and customer satisfaction performance in SMEs. Equally, this means that achieving customer satisfaction amongst SMEs is now somewhat determined by social sustainability practices [54,55]. Lastly, employee satisfaction was closely associated with social sustainability practices. Accordingly, the positive and significant relationship between social sustainability and employee satisfaction performance confirmed in the study is consistent with existing empirical studies [56]. This then follows that increasingly employees are scrutinising social sustainability issues of SMEs.

The confirmation of all the postulated hypotheses in this study has several implications. Firstly, the reviewed literature indicated that amongst the three areas of sustainability, namely, economic, environmental and social, little effort has been directed towards the area of social sustainability. The findings of this study are therefore essential as a justification for business practising social sustainability. While in the past, social issues were only a concern for large businesses, these findings further substantiate that even small businesses need to be proactive as this has broad effects on the other areas of firm performance. Especially, considering the closer and dyadic relationship between small businesses and the society, it may be found that small businesses need to social sustainability practices more than large organisations. The owner/managers need to consider the two parental variables investigated in this study. As such, managers and owners of SMEs in developing countries cannot ignore social sustainability concerns as highlighted by its vitality to shareholders, customers and employees, respectively. These findings indicate the need to consider social sustainability as a competitive advantage tool by SMEs.

In the same regards, governments, policymakers, as well as business practitioners, need to consider the huge possibility for SMEs to be instrumental in advancing social sustainability especially considering that SMES are usually located in areas that are socially disadvantaged. Thus, though it is generally consented that there is an increasing growth in the rate that social sustainability is being practised by businesses, the rate of adoption and practice can be increased. As part of recommendations, there is a need to ensure that social sustainability becomes institutionalised as a business practice. Researchers, academics and policymakers have a huge role to ensure that there is some form of codification in the social sustainability spectrum. These results need to be interpreted within the constraints of the study. The major limitation is that the study only considered one developing country, namely South Africa. Again, the study was only focused on one specific province of South Africa, namely, Limpopo province. Thus, future studies can adopt a broader spectrum of the study area and can pursue a comparative approach between developing and developed countries in order to establish the differences in the effects of social sustainability.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Limpopo.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Research Instrument

Indicate with an X to what extent do you agree to your firm applying the following sustainability practices by using the scale below where: 1 = Strongly Disagree and 5 = Strongly Agree.

| Social Sustainability Our Sustainable Business Practices | |||||

| take current activities in the community into account | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| consider the social well-being of society | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| promote women to senior management positions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| focus on equity and safety of the community | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| focus on improving the general education level | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| promote individual rights both civil and human rights | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Rate the performance of your business in the past three years in the following areas indicating with an X using the scale below where: 1 = Significant decline to 5 = Significant increase.

| Financial Performance | |||||

| Net revenue | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Gross Profit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sales growth relative to competitors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Number of Employees | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Market Share | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Customer Satisfaction Performance | |||||

| Sales (turnover) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Customer service | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Relations with customers | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Customer loyalty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Employee Satisfaction Performance | |||||

| Employee remuneration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The working environment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Employees’ loyalty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Employees’ morale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- Rishi, M.; Jauhari, V.; Joshi, G. Marketing sustainability in the luxury lodging industry: A thematic analysis of preferences amongst the Indian transition generation. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borim-de-Souza, R.; Balbinot, Z.; Travis, E.F.; Munck, L.; Takahashi, A.R.W. Sustainable development and sustainability as study objects for comparative management theory. Cross Cult. Manag. 2015, 22, 201–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masocha, R.; Fatoki, O. The Role of Mimicry Isomorphism in Sustainable Development Operationalisation by SMEs in South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, G.S.; Erasmus, B.J.; Strydom, J.W. Introduction to Business Management, 8th ed.; Oxford Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2010; ISBN 9780195992519. [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah, E.S. Customer based brand equity (CBBE) and the competitive performance of SMEs in Ghana. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, X. Thrive, not just survive: Enhance dynamic capabilities of SMEs through IS competence. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2011, 13, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEDA. SMME Quarterly Update 1st Quarter 2018—The Small Enterprise Development Agency. 2018. Available online: http://www.seda.org.za/Publications/Publications/SMME%20Quarterly%202018-Q1.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Masocha, R. Delineating Small Businesses’ Performance from a Contemporary Sustainable Development Approach in South Africa. Acta Univ. Danub. 2018, 14, 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sy, M.V. Impact of sustainability practices on the firms’ performance. Asia Pac. Bus. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 4, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sarango-Lalangui, P.; Alvarez-Garcia, J.; de la Cruz del Rio-rama, M. Sustainable Practices in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Ecuador. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaga, N.; Masurel, E.; Van Montfort, K. Owner-manager motives and the growth of SMEs in developing countries. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 7, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, J.; Quartey, P. Issues in SME Development in Ghana and South Africa. Int. Res. J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 39, 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Apulu, I.; Latham, A.; Moreton, R. Factors affecting the effective utilisation and adoption of sophisticated ICT solutions. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2011, 13, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade and Industry. Department of Trade and Industry Annual Report 2010/2011. 2010. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/annual_report2011-all.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2017).

- Bosch, G.; Tait, M.; Venter, E. Business Management: An Entrepreneurial Perspective, 2nd ed.; Lectern: Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, W.S.; Chen, Y. Corporate Sustainable Development: Testing a New Scale Based on the Mainland Chinese Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, L.A.; Zhang, D.D. Perspectives on corporate responsibility and sustainable development. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 23, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogt, H.J.T. Recent and future management changes in local government: Continuing focus on rationality and efficiency? Financ. Account. Manag. 2008, 24, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turyakira, P.; Venter, E.; Smith, E. The impact of corporate social responsibility factors on the competitiveness of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2014, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polášek, D. Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Medium-Sized Companies in the Czech Republic. Ph.D. Thesis, Czech Management Institute, Praha, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, M. Unlocking the social domain in sustainable development. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 12, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgevold, N.M.; Svensson, G.; Klopper, H.B.; Wagner, B.; Valera, J.C.S.; Padin, C.; Ferro, C.; Petzer, D. A triple bottom line construct and reasons for implementing sustainable business practices in companies and their business networks. Corp. Gov. 2015, 15, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Troisi, O. Sustainable value creation in SMEs: A case study. TQM J. 2013, 25, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, M.J.; Moreno, P.; Tejada, P. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance of SMEs in the services industry. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2015, 28, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.B.; Brito, L.A.L. Toward a Subjective Measurement Model for Firm Performance. Braz. Acad. Rev. 2012, 9, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Does the firm size matter on firm entrepreneurship and performance? US apparel import intermediary case. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2009, 16, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcnair, C.J.; Lynch, R.; Cross, K.F. Do Financial and Non-financial Measures Have to Agree? Manag. Account. 1990, 75, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lukviarman, N. Performance measurement: A stakeholder approach. Sinergikajian Bisnis Dan Manaj. 2008, 10, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Nason, R.S. A Stakeholder Perspective on Family Firm Performance. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, C.; Padin, C.; Høgevold, N.; Svensson, G.; Varela, J.C.S. Validating and expanding a framework of a triple bottom line dominant logic for business sustainability through time and across contexts. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, T.T.; Ramamoorthy, N.; Flood, P.C.; Guthrie, J.P.; MacCurtain, S.; Liu, W. The role of human capital philosophy in promoting firm innovativeness and performance: Test of a causal model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavou, H.; Avlonitis, G. Product innovativeness and performance: A focus on SMEs. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matari, E.M.; Al-Swidi, A.K.; Fadzil, F.H.B. The Measurements of Firm Performance’s Dimensions. Asian J. Financ. Account. 2014, 6, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambharya, R.B. Security analysts’ earnings forecasts as a measure of firm performance: An empirical exploration of its domain. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1160–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cabañero, C.; González-Cruz, T.; Cruz-Ros, S. Do family SME managers value marketing capabilities’ contribution to firm performance? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulak, M.E.; Turkyilmaz, A. Performance assessment of manufacturing SMEs: A frontier approach. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A. Corporatesustainability performance and firm performance research. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provincial Review, Limpopo. Real Economy Bulletin. Available online: https://www.tips.org.za/images/The_REB_Provincial_Review_2016_Limpopo.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2017).

- Seda. The Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise Sector of South Africa, Research Note. 2016. Available online: http://www.seda.org.za/Publications/Publications (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Sachdeva, J.K. Business Research Methodology; Himalaya Publishing House: Mumbai, India, 2013; pp. 69–205. ISBN 9788184881622. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J.; Carr, J.C.; Griffin, M. Business Research Methods, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: South Melbourne, Australia, 2010; pp. 308–594. ISBN 1133190944. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 123–185. ISBN 10 0803953186. [Google Scholar]

- Asoka, M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS; Nippon Graphics Pvt. Ltd.: Panadura, Sri Lanka, 2015; pp. 23–60. ISBN 978-95542134-0-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P. Business Research Methods, 10th ed.; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 564–626. ISBN 9780077129972. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.D.; Lacker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeh, M.; Tookey, J.E.; Rotimi, J.O.B. Estimating transaction costs in the New Zealand construction procurement: A structural equation modelling methodology. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2015, 22, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.; Grønhaug, K. Research Methods in Business Studies, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall Financial Times: London, UK, 2010; pp. 81–194. ISBN 978027371204. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P. Business Research Method; Oxford University Press: New Dehli, India, 2015; pp. 620–627. ISBN 9780198094739. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, P.; Chauhan, A. Factors affecting the ERP implementation in Indian retail sector: A structural equation modelling approach. Benchmark. Int. J. 2015, 22, 1315–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassala, C.; Apetrei, A.; Sapena, J. Sustainability Matter and Financial Performance of Companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Thai, V.V.; Grewal, D.; Kim, Y. Do corporate sustainable management activities improve customer satisfaction, word of mouth intention and repurchase intention? Empirical evidence from the shipping industry. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; La, S. The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer trust on the restoration of loyalty after service failure and recovery. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Fernández-Salinero, S.; Topa, G. Sustainability in Organizations: Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility and Spanish Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).