1. Introduction

In the discourse about the functioning of the culture sector, there are various views about the role of the state in culture, the scope of culture protection, forms of its financing, importance of the market system in culture, the institutional shape of the culture sector, the status of artists and their masterpieces, and the approach to the consumer. Approaching culture, the related mechanisms, and the principles of its functioning in the categories of autotelic value or instrumental value, state or market, cost or investment, art or product, or culture recipient or consumer without considering intermediate states is an over-simplification because perceiving culture as sacred does not mean the lack of a need to implement in this sphere the marketing concepts that are an expression of the market orientation of cultural institutions.

When analyzing how the concept of market orientation is defined, the factors determining the success of a market entity should be considered. These factors can be both external and internal, and thus concern the environment or resources and processes occurring inside the market entity. This means that people managing various types of market entities can adopt an exogenous perspective or an endogenous perspective [

1]. Market orientation is located within external orientations.

Many features and related explanatory variables prove the complex nature of the concept of market orientation. Contrary to production, product, or sales orientation, market orientation involves thinking about the way in which a market entity functions. Understanding consumers and satisfying their needs better than the competitors is the essence of market orientation. Market orientation is also characterized by obtaining and using market information by management, which enables considering current and future needs of consumers in the offer they create. When defining market orientation Kohli and Jaworski emphasized that all organizational divisions and units, and not only marketing services, should be involved in the process of goal achievement. The scope of the implementation of the principles of marketing concepts, and compliance of an organization’s management with the assumptions of the marketing approach proves the level of market orientation of a market entity [

2]. Day emphasized that market-oriented entities are characterized by openness and participatory organizational culture in which meeting consumers’ needs are the priority. The employees of market externally-oriented entities take risks and have knowledge about actions conducted by competitors [

3].

Therefore, market orientation is a condition that is necessary for the emergence of marketing as a specific way of thinking and acting in the market. The role of marketing that is associated with culture functions in this sphere is frequently expressed in finding the appropriate audience for artworks [

4]. When describing the significance of marketing in the cultural sector, Colbert similarly noticed that, in the case of cultural institutions, applying marketing principals does not mean that the artist has to create the artwork adjusting to the recipients’ needs and tastes. Marketing in culture is defined in the context of reaching the market segments that may be interested in the artwork. The forms of artwork promotion, methods of its distribution, and pricing policy should be adjusted to recipients’ needs. Therefore, enabling consumers to contact the artwork and consequently achieve goals related to the mission of cultural institutions are the premises for the application of marketing. The role of marketing is perceived through the prism of the symbolic dimension of cultural experience, brand of cultural institution, and artwork, shaping the tastes of culture recipients, establishing relationships with them, and developing culture sensitivity that does not only include satisfaction of currently experienced needs [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Consumers, artists, as well as their works are the center of interest of marketing. In this context, providing contact between artists, their works, and culture consumers is essential [

11].

The satisfaction of culture participants’ needs by the creator does not exclude the creators’ and artistic circles’ needs in the processes of creation. Recipients toward whom the creator orients their creativity do not need to have different tastes or perceptions of art.

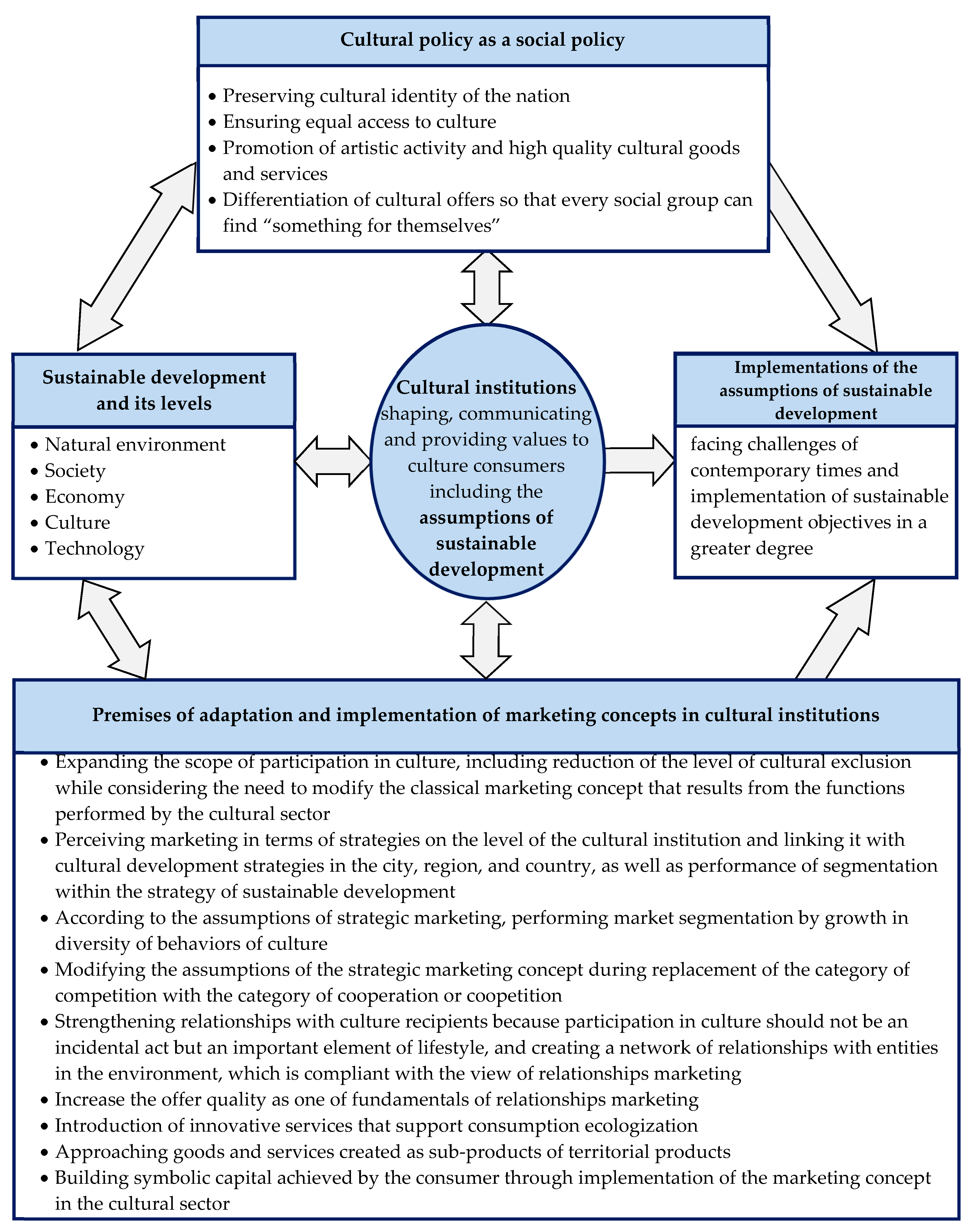

Simultaneously, development of both marketing and culture has a multidirectional and multi-paradigmatic nature, and has relationships with the concept of sustainable development (

Figure 1). Sustainable development oriented toward economic growth and equal distribution of profits, protection of natural resources and the environment, and reduction of the scale of social exclusion, has a series of implications for the cultural policy of the state or region, or management of cultural institutions. Sustainable development includes such spheres as economy, society, environment, and culture [

12], and is a process aimed at the satisfaction of current aspirations without compromising the ability of future generations to achieve the same aspirations [

13]. Reduction of poverty and social exclusion, and maintenance of cultural diversity are the essence of sustainable development [

14]. This consequently causes sustainable development to be a type of social-economic development implemented by people for people and integrating all human activity in social, economic, environmental, technological, and cultural dimensions. It also represents the desired living environment and a responsible society that implements concepts of intra- and inter-generational order [

15].

Relationships between sustainable development and culture are expressed by the development of the cultural policy, in which culture is perceived as a factor accelerating development, and by the introduction and promotion of the cultural dimension in other public policies [

16]. References to the concept of sustainable development can be found in the goals of cultural policies of many countries [

17]. Implementation of the assumptions of the concept of sustainable development is not possible without shaping the attitudes and behaviors supporting this development in society [

18]. Culture institutions that, through their mission and actions, impact society in the implementation of the assumptions of sustainable development should be active in this process. Therefore, the role of culture in sustainable development should not be ignored because it is a determinant of such development and enables sustaining the functioning of societies [

19,

20].

Considering the abovementioned relationships between culture and sustainable development, these categories are also closely related to marketing, and can be both a part of the issue as well as a part of its solution [

21]. Applying marketing that considers contemporary challenges should enable changing consumer societies into societies respecting the principles of sustainable development. This is reflected in the concept of sustainable marketing, which is described as the process of creation, communication, and provision of values to consumers in a way that protects and strengthens natural and human capital [

22]. This also includes cultural institutions that apply the classical marketing concept and the relationship marketing concept. Implementation of the assumptions of the classical concept of marketing should translate into the expansion of the scope of cultural participation through raising awareness and stimulating motivation for participation in culture among people who have not used cultural offer before. It is associated with the concept of sustainable development. Strengthening relationships with culture recipients and other market entities, increasing their loyalty, and building valuable relationships with entities in the environment are the result of implementing the major assumptions of the concept of relationship marketing. High quality offers are also the essence of relationship marketing [

23,

24]. Cultural institutions also apply the concept of strategic marketing, which includes the idea of market segmentation and diversification of marketing activities. Such an approach enables combining the strategy implemented at the level of the cultural institution with development strategies, including sustainable development, of the cultural sector at the city, region, and country levels.

It is important that the application of marketing expressed in market orientation, innovations (including those based on new media), and the high value of the offer of cultural institutions have positive impacts on culture sustainability [

25].

The performed survey of the literature concerning market orientation, marketing in culture, and sustainable development showed that a research gap exists that is related to how managers of cultural entities in Poland perceive the market orientation of cultural institutions and the place of culture consumers among groups of recipients of actions conducted by these institutions, and also whether development of offer diversity included in the concept of sustainable development is perceived in terms of raising quality of cultural offer. The hypotheses presented below are addressed to filling this identified research gap.

2. Materials and Methods

To fill the identified research gap, it was necessary to design and perform empirical research. Before the start of design and then during the implementation and interpretation of results, literature reviews were conducted in the sphere of research methods and techniques [

26,

27,

28,

29] to develop a research procedure that was appropriate from the point of view of both the analyzed subject area, marketing, and the specific characteristics of the culture sector.

The conducted empirical study included a set of objectives aimed at the recognition of how the concept of market orientation is understood by people managing cultural institutions in Poland, description of the place that participants in culture occupy among groups of consumers receiving marketing actions performed by cultural institutions, and checking for a correlation between expansion of the offer diversity as a determinant stimulating development of the culture market and improvement of the quality of the offer created by cultural institutions. Empirical research was implemented within the research project entitled “Determinants and perspectives of development of market orientation in the culture sector”, funded by the National Science Centre.

In the research procedure, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The ways in which market oriented cultural institutions are perceived more often reveal the focus on culture consumers rather than the financial aspect of activity conducted by the entities creating cultural offers.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Culture participants are the most important group of recipients of actions conducted by cultural institutions.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Increase in offer diversity as the factor stimulating development of cultural market, which is included in the concept of sustainable development, is strictly related to improvement of the quality of cultural institutions’ offers.

Quantitative research was conducted on a Poland-wide sample of cultural institutions selected using a probability sampling method. The respondents included general managers, managers and artistic directors, heads of marketing, promotion and sales departments, and owners of cultural institutions.

Identification of the general population required considering a complete list of cultural institutions, which included all entities operating in the culture sphere, including organizational and ownership criteria, complying with the demand for timeliness and consistency with the type of activity in the sphere of culture declared at the time of registration with actually conducted activity. On the basis of analyses of available data and publications on the subject of culture market, even the National Business Registry Number (REGON) register had some deficiencies because the registering entities frequently declare a broader scope of activities according to the Polish Classification of Businesses Code (PKD) than they actually conduct. However, the register is not always updated. As such, actions were aimed at increasing the opportunity to reach the entities providing cultural offers in Poland and forming possibly the best representative research sample. The list of entities was created on the basis of integration of the Bisnode company database used by ARC Rynek i Opinia (ARC Market and Opinion) research institute, and lists made available by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, Adam Mickiewicz Institute, and the Polish Film Institute, among others. All cultural entities occurring in the integrated database were checked to determine whether they were still functioning or still active in the sphere of culture. For this purpose, webpages and their timelines were checked, and if up-to-date content was absent, phone calls were made to confirm that a given entity conducts activity in the sphere of culture. The database created for the purpose of the study constituted the most up-to-date and representative collection of culture entities that were consistent with the research assumptions.

The research was designed to be non-exhaustive. Stratified random sample selection was applied as the main method of entities selection. In the process of sample selection, the studied population was divided into six separate strata out of which the entities for research were randomized in the next stage. Strata were distinguished with respect to the type of conducted activity, The research included 451 cultural institutions, including: museums, art galleries and exhibition rooms, theatres and musical institutions, cinemas, cultural centers (excluding sitting rooms, clubs, and circles), and publishers (excluding publishers of educational, academic, scientific, professional books and other specialist publications and incidental publishing entities).

The structure of the research sample by type of cultural entity is presented in

Table 1.

The number of entities studied within specific groups was proportional to the number of institutions functioning in particular areas found in the integrated database of cultural entities.

The studied market entities represented all voivodeships in Poland. Over 68% of studied entities belonged to self-governed cultural institutions, 7.5% were state-owned cultural institutions, and the other 23.9% were private institutions. With respect to the number of workers employed on the basis of employment contract, among the studied institutions, there were both micro-entities as well as large entities employing over 100 people, which constituted 8% of the studied population. The studied cultural markets entities were also diversified in terms of the period of functioning. The short-term entities functioning on the market (no longer than five years) constituted 8.2% of the research sample and the oldest, functioning more than 100 years, represented 4.2%. Considering the size of the city where the cultural institutions were located, the largest group were located in cities of over 200,000 residents. Their share in the studied population was 46.4%. The sample structure including its most important characteristics is shown in

Table 2.

Considering the scope of this quantitative research, the type of respondents, and the nature of their work, the computer-assisted telephone interview technique (CATI) was selected. The choice of the technique was dictated by the need for standardization of the interview process and minimization of the interviewer effect [

30]. This technique allowed for flexible adjustment of the date of interview to accommodate respondent’s preferences.

When establishing the content, type, number, and order of questions, the principles that are applied in marketing research were considered. To determine the duration of the interview, recognition of respondents’ reactions to individual questions, and to check whether the questions were unambiguous, unclear, or did not cause difficulties for respondents, a pilot experiment was conducted. The questionnaire was also tested via telephone.

Technical execution of the computer-assisted telephone interviews with the use of a standardized questionnaire occurred in the CATI studio of the ARC Rynek i Opinia (ARC Market and Opinion) research institute in Warsaw, Poland that is equipped with professional devices and software that ensures appropriate research process. The application of the CATI technique reduced the possibility of errors because the program controls the logical correctness of the introduced answers. IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM Corp., 2016, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to statistically analyze the collected data. The operations on the data set that involved sorting and aggregation were performed through computer processing of data. Subsets of data for the analysis were separated. Quantitative analysis was applied with the use of descriptive statistics to recognize how market orientation and marketing in the studied cultural institutions is understood and approached. Correlations between the variables were determined.

3. Results

Aiming at recognizing how the notion of market orientation in the cultural sector is understood by decision-makers in cultural institutions, a semantic network was created. Semantic networks, which consist of bundles and links, allowed the identification of mental representations and processes [

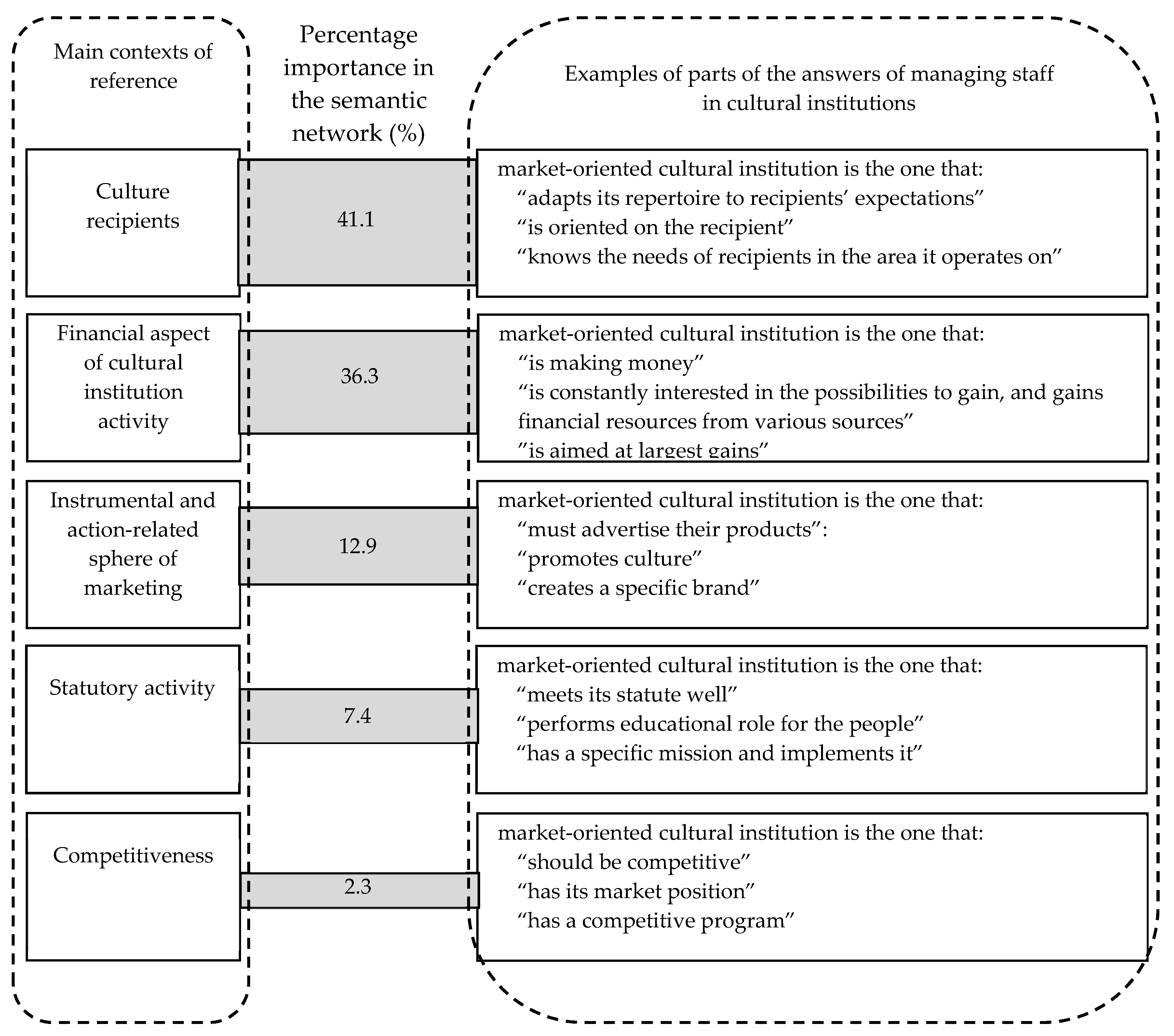

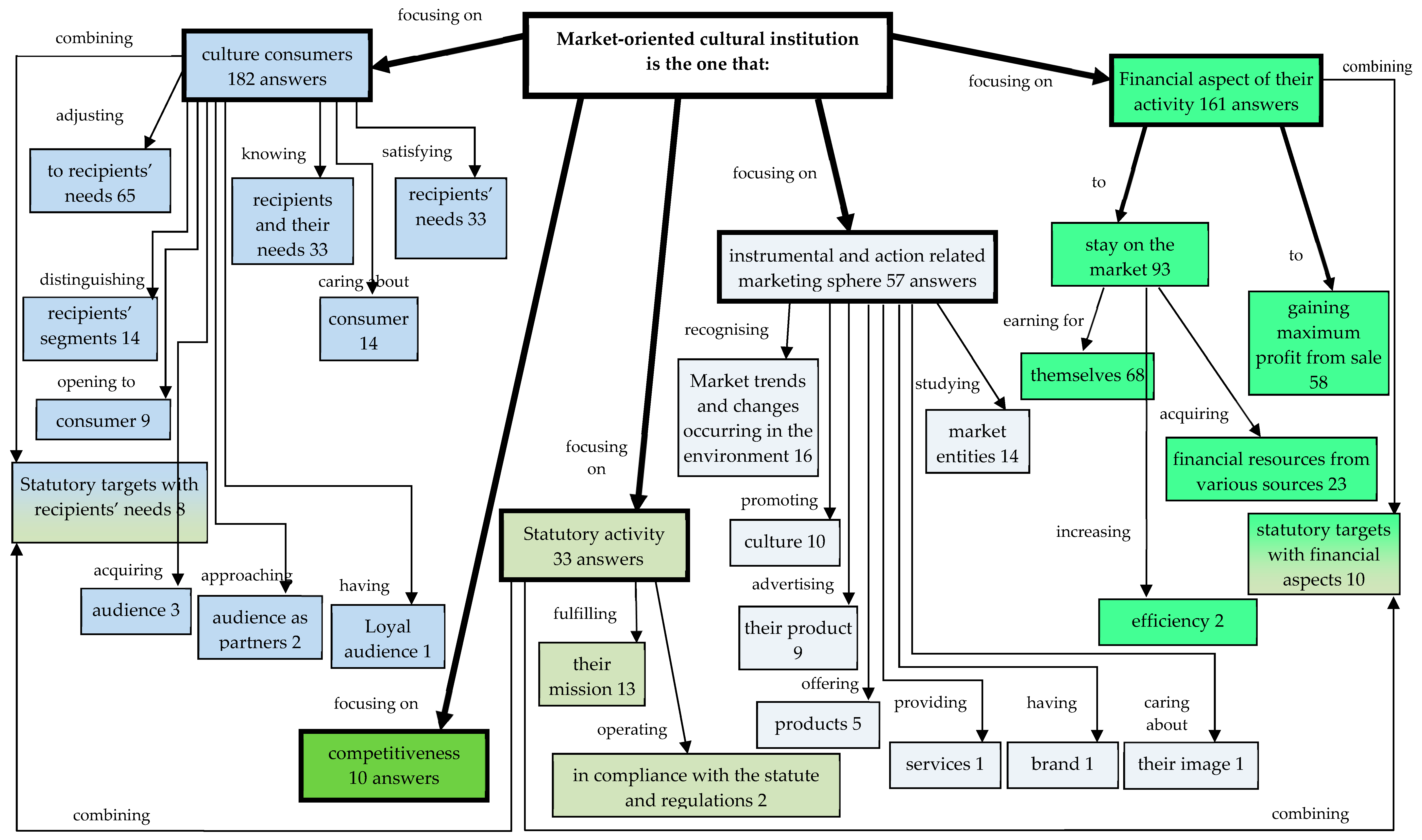

31] in terms of how decision-makers in cultural institutions perceive the category of market orientation. Analyzing the managing staff’s answers to the open-ended questions asked in the quantitative study concerning distinguishing features of market-oriented cultural institutions, the individual answers in relation to the mechanisms of the formation of meanings that are reflections of cognitive processes and methods of conceptualization of notions were analyzed. The question was: “Please finish the following sentence: A market-oriented cultural institution is one that… “. Analyzing the semantic area, the keywords were identified and then were categorized according to the functions they performed in respondents’ statements, when simultaneously considering the notions characterizing the studied issue, associations, and equivalents that could replace the keywords. The process aimed at an accurate reproduction of the respondents’ intentions. The analysis of the semantic area that emerged from the phrases allowed the identification of the thoughts about market-oriented cultural institution. The analyzed semantic field depicts the image of a market-oriented cultural institution as viewed in the minds of decision-makers’ in cultural institutions as one focused on culture recipients, the financial aspect of their activity, the instrumental and action-related sphere of marketing, statutory activity, and increase in competitiveness. The ways in which decision-makers in cultural institutions in Poland understand the notion of market-oriented cultural institution are presented in

Figure 2 and the whole semantic network is shown in

Figure 3.

The semantic network of the notion of market-oriented cultural institution shown in

Figure 3 has a hierarchical nature. It was constructed on the notion that respondents’ opinions aptly describe the essence of market orientation and the bundles and links present relationships occurring between major bundles and bundles that specify the main bundles. The notions that occur in the semantic area are found in the figure with greater frequency closer to the studied category, which is the market-oriented cultural institution.

The key conceptual relationships occurring between the analyzed category of market-oriented cultural institution and major links (culture consumers, financial aspect of cultural institution activity, instrumental and action-related marketing sphere, statutory activity, and competitiveness) are shown in the

Figure 3 in bold. Other categories specify how the notions included in major links are perceived and consequently indicate the context of the respondents’ definition of market-oriented cultural institutions.

Considering the research objectives, apart from identifying the method for market orientation by people managing cultural institutions in Poland, the groups of consumers to which entities are shaping and aiming their cultural offer are important. This results from both the development of marketing thought and the significance of the concept of relationship marketing, for which it is characteristic to approach the recipients of marketing activities from the context of relationship networks created, with many internal and external partners, as well as from the context of the many entities whose needs are satisfied by cultural institutions. The results from the cultural institutions in Poland show that they attach importance to the satisfaction of recipients’ needs. Almost 98% of respondents (

Table 3) classified culture participants into one of four groups of entities on whose satisfaction of needs and expectations the cultural institutions are oriented on.

The high ranking of culture participants in the groups of recipients of cultural institutions is proven by the analysis of the correlations between the type and location of an entity in the hierarchy of importance of addressees of actions undertaken by cultural institutions. People managing cultural institutions that indicated culture recipients as one of four priority groups of stakeholders almost always placed them in the first position in the ranking (V-Cramer coefficient = 0.537;

Table 4). Of respondents, 88.5% placed culture consumers at the top of the hierarchy of importance of groups of recipients. The workers, including creators and artists, were ranked as the most important groups whose satisfaction of needs and preferences a cultural institution was the focus, as indicated by slightly over 7% of respondents. Analysis of the V-Cramer coefficient value showed a correlation between including creators, artists, and other workers to one of four entities most important for cultural institutions and ranking them second in the hierarchy (V-Cramer coefficient = 0.527). Of the respondents, 36.1% ranked the group of creators, artists, and other workers in second place the groups of entities whose needs and preferences are satisfied by cultural institutions.

As culture participants ranked first among the groups of recipients of actions undertaken by cultural institutions in Poland, the answer to the question about how decision-makers in cultural institutions offer diversity within the concept of sustainable development seems important.

The conducted questionnaire survey shows that people managing cultural institutions in Poland perceive an increase in offer diversity as a stimulant of the development of the culture market. This is proven by this factor reaching a mean value of 6.04 on the seven-degree scale, where one represented unimportant stimulant and seven represented a very important stimulant of culture market development in Poland. According to the respondents, improving the quality of the offer created by cultural institutions was an almost equally important factor determining the development of the culture market in Poland (average score 6.02). Therefore, the results of the research show that decision-makers in cultural institutions have an active attitude toward the market and want to shape its development through increasing the attractiveness of the cultural offer. The analysis of results was completed with observed correlations between perceiving the increase in the diversity of the cultural institution offers as a stimulant of cultural market development and experiencing the need to expand the scope of the conducted marketing actions (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ2 = 14.146, degrees of freedom (df) = 2, p-value = 0.000). Decision-makers in cultural institutions in Poland stated that, in the market entities they represented, the scope of marketing operations should definitely be expanded and greater importance should be attributed to increasing the diversity of the cultural offer as a factor determining development of culture market.

Analysis of correlations between scores provided by decision-makers in cultural entities to the individual factors that are stimulants of the culture market in Poland revealed correlations between high scores attributed to certain factors (development of the offer diversity) and an increase in the quality of the created cultural offer (Spearman rank correlation coefficient = 0.710). Therefore, these respondents typically perceive market development in the context of factors that are directly influenced by people managing cultural institutions. This should be considered an expression of the market orientation of these cultural institutions.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Theoretical constructs of market orientation and related explanatory variables, including those oriented on buyer, oriented on competitors, coordination of functions of market entities, long-term horizon, acquisition and use of information, as well as efficiency are important references for empirical data constituting the basis for the creation of semantic networks for evaluating the notion of “market oriented cultural institution” [

33].

The frequency of occurrence of individual contexts revealing the way in which respondents perceive the concept of market orientation of a market institution is diverse. Decision-makers in cultural institutions most often defined a market-oriented institution as one that focuses on recipients, including satisfying and adjusting to their needs and separation of segments, among others. This is consistent with the assumption of the marketing concept that satisfaction of consumer needs and expectations is the basis for achievement of the targets of a market entity. The share of this trend of responses in the semantic network was 41.1%.

Categories, such as loyalty and partnership, rarely occurred in respondents’ statements. Therefore, spontaneous respondents’ statements did not reflect thinking about market orientation in the context of the assumptions of relationship marketing or partnership marketing on a large scale.

Referring to a cultural institution’s financial aspect of functioning was the next most frequent way of defining market-oriented cultural institution in the respondents’ statements. The categories related to the financial functioning of a market entity were found in 161 statements. The statements of decision-makers in cultural institutions who perceived market orientation through the prism of financial variables can be divided into two groups. The first includes the statements of decision-makers who identified market orientation with a continuing presence in the market as well as seeking and acquiring financial resources for conducting cultural activity from various sources. The second group includes statements about perceiving market orientation as acting in a targeted profit-making way. This latter approach to market orientation does not reflect its essence and may pose a risk of economic targets becoming more important than the statutory and artistic goals of a cultural institution. Considering the specific characteristics and roles of cultural institution, a desirable situation is when the achievement of economic goals enables achievement of artistic targets. Subordination of creative processes to achievement of only economic goals is typical of the sales-oriented approach and is not compliant with the assumptions of the marketing concept, where satisfaction of consumers’ needs is the key to achievement of goals, including financial goals [

34].

Categories associated with the instrumental and operational spheres of marketing formed the third group of statements that was used by a significantly smaller group of respondents defining market orientation. In this case, the method through which a cultural institution approaches market-orientation is one that recognizes market trends and studies entities emerging in the market environment. This way of describing the institutions is consistent with one of the key principles of marketing concepts, i.e., market research, where the essence of market orientation is acquiring information about the market, including information about current and future consumer needs [

2]. The majority of the other descriptions of market orientation in this group referred to marketing instruments and associated operations. Among the ways in which market orientation was defined by respondents, there were no direct references to marketing strategies or the process of marketing management.

Defining market orientation through the prism of fulfilment of a mission and operating in accordance with the statute was barely present in respondents’ minds.

Improvement of competitiveness in the market was the last identified category that, in the respondents’ view, is a distinctive feature of the market orientation of a cultural institution. This type of explanation of the studied category occurred in 10 statements.

A small group of respondents linked the issues associated with statutory activity with satisfying recipients’ needs or financial aspects, while explaining what market-oriented cultural institution means to them.

The conducted analysis of the quantitative research results with the use of the semantic network provided the basis for the positive verification of H1, the category of focusing on culture recipients rather than the financial aspects of activity conducted by entities creating a cultural offer is revealed in the ways of perceiving of market-oriented cultural institutions. The presented semantic network was completed with the results that showed that even though not all respondents indicated cognition, satisfaction of recipients’ needs while answering the open-ended question concerning distinctive features of market-oriented cultural institutions, 97.8% of studied respondents agreed with the statement that striving to meet the needs of culture consumers is important to management. Only 10 of the 451 studied representatives of cultural institutions (2.2%) thought it was not significant.

Among the premises for starting actions aimed at the satisfaction of consumers’ needs, the conviction was prevailing that if a cultural institution has consumers, artistic actions gain sense and significance (88.7% of studied cultural institutions are aimed at satisfying consumers’ needs). Only 11.3% of cultural institutions taking consumer needs into consideration do so because of the wish to increase income. This proves that decision-makers in the studied cultural institutions perceive the consumers as a recipient who gives meaning to creative work rather than as a source of income.

The analysis of the V-Cramer coefficient for hierarchy of importance of groups of recipients of actions conducted by cultural institutions showed that H2 (a culture participant has a high (or even the highest) ranking among the recipients of actions by cultural institutions in Poland) is true. This constitutes one of the expressions of market orientation applied by cultural institutions.

While discussing the results this research and results of analyses in the literature, attributing a high significance to the satisfaction of recipients’ needs by cultural institutions can result from the goal of cultural institutions, which is the creation and popularization of art, building cultural experiences, and conducting dialogue with the recipients [

35]. Participation in culture, in terms of combining perception, expression, and transformation, is an expression of the internal activity of a human being and the expression of their internal life. This is related to the many processes of the sensory reception of the artwork, its interpretation, the mechanisms of providing messages, and transforming symbolic messages and their valuation. Understanding the behaviors of culture participants requires conducting public surveys. The qualitative method described as theatre talks allow for exploring theatrical experiences and increasing knowledge resources applied in audience development, which is based on community, connections, collaborations, and caring [

36,

37]. This method should be applied here. This method can also be implemented in other cultural fields.

The people managing cultural institutions in Poland, indicating the needs of the recipients to which they cater as being of crucial importance, consider the lack of cultural education in Poland to be a significant barrier to the development of the cultural market. There is a need to expand the cultural and aesthetic competences of the recipients that are perceived in the predisposition of individuals to participate in culture and to understand the codes and interpretations of artworks. This is especially vital in a culturally diversified world [

38].

Consequently, the results of this conducted empirical research mean that openness of cultural institutions to satisfaction of recipients’ needs is not accompanied by the willingness to create an offer that is easy to consume, and the development of the culture market is seen in shaping knowledge and skills associated with reading codes included in culture and creation of positive attitudes toward participation in culture. The results of the conducted empirical research also show that people managing cultural institutions in Poland perceive the development of offer diversity as a stimulant of the development of the culture market. This factor is correlated with increasing the quality of the cultural offer. This constitutes the basis for the verification of H3, which stated that an increase in offer diversity, included in the concept of sustainable development and as a factor stimulating development of the culture market, is closely related to increasing the quality of the offer of a cultural institution.

Given the analysis of the results, many recommendations for the implementation of marketing concepts in the culture sector are possible. The attainments in the area of classical marketing concepts, relationship marketing, strategic marketing, marketing of services, territorial marketing, as well as sensation and experience marketing can be applied in the management of the cultural sector. Regardless of which marketing concept, both at the theoretical level and in management practice, is implemented in culture sector, there is a need to adapt some assumptions associated with the philosophy of marketing to the specific characteristics of the cultural sector. Market orientation and implementation of marketing principles in the sphere of culture involves finding the appropriate audience for artworks that are the result of the creative process, and thus reaching market segments that are interested in the artwork. Applying marketing that is an expression of market orientation should facilitate the implementation of the assumptions of sustainable development. In this case, marketing emerges as one of the ways to solve current problems and challenges as well as building a society that respects the principles of sustainable development. This requires cultural institutions to consider the idea of sustainable development while shaping, communicating, and supplying value to culture recipients.

The development of market orientation in the culture sector is not possible without cultural education aimed at shaping the cultural competences of recipients—artistic education— as well as managerial education, allowing for development of creative capital of artistic circles. This education should translate into management efficiency and shaping the set of values offered to culture participants while considering the assumptions of sustainable development.

In terms of application, the literature and the results here show that the use of innovative marketing solutions by cultural institutions should translate into stimulating people who previously have not used cultural institution offers to participate in culture. Consequently, this will reduce the distance observed between active culture consumers and people who have not previously used the offer of a cultural institution. This is the expression of responsible management in the culture sector because development of an individual cannot occur without participation in culture. There is a need to enhance the relationships of cultural institutions with existing offer consumers. This requires ensuring the quality of the offer and diversification of marketing actions as well as development of knowledge about the behaviors of culture recipients.

Each study has its limitations. The scope of future studies on the role of the marketing of cultural institutions in the context of sustainable development should be expanded to include cultural institutions from countries in various stages of socio-economic development. The countries with various models of cultural state policy and different attitudes of the state toward the scope and forms of financing the culture sector should be investigated. In cognitive terms, determining the differences in the role attributed to marketing in processes of creation of value for culture participants in the American market and in selected European and Asian markets could provide valuable insights. In further studies, applying other methods of statistical analysis to improve the scope of the interpretation of the results would be useful. Re-measurement on a similar sample of cultural institutions to recognize changes in the application of marketing in the culture market in Poland and how this translates into reducing inequalities in the access to culture is another trend for future research. Another avenue for future quantitative marketing research is implementation among culture, especially because the development of the culture market depends on aptitude for dialogue with the audience. This trend in further research on market orientation would help determine how culture participants perceive their role in the process of value creation and the role of the cultural institution in the implementation of the assumptions of sustainable development.