How does Perceived Destination Social Responsibility Impact Revisit Intentions: The Mediating Roles of Destination Preference and Relationship Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Destination Social Responsibility

2.2. Destination Preference

2.3. Relationship Quality

2.3.1. Tourist Satisfaction

2.3.2. Tourist-Destination Identification

2.4. Revisitation of Intentions

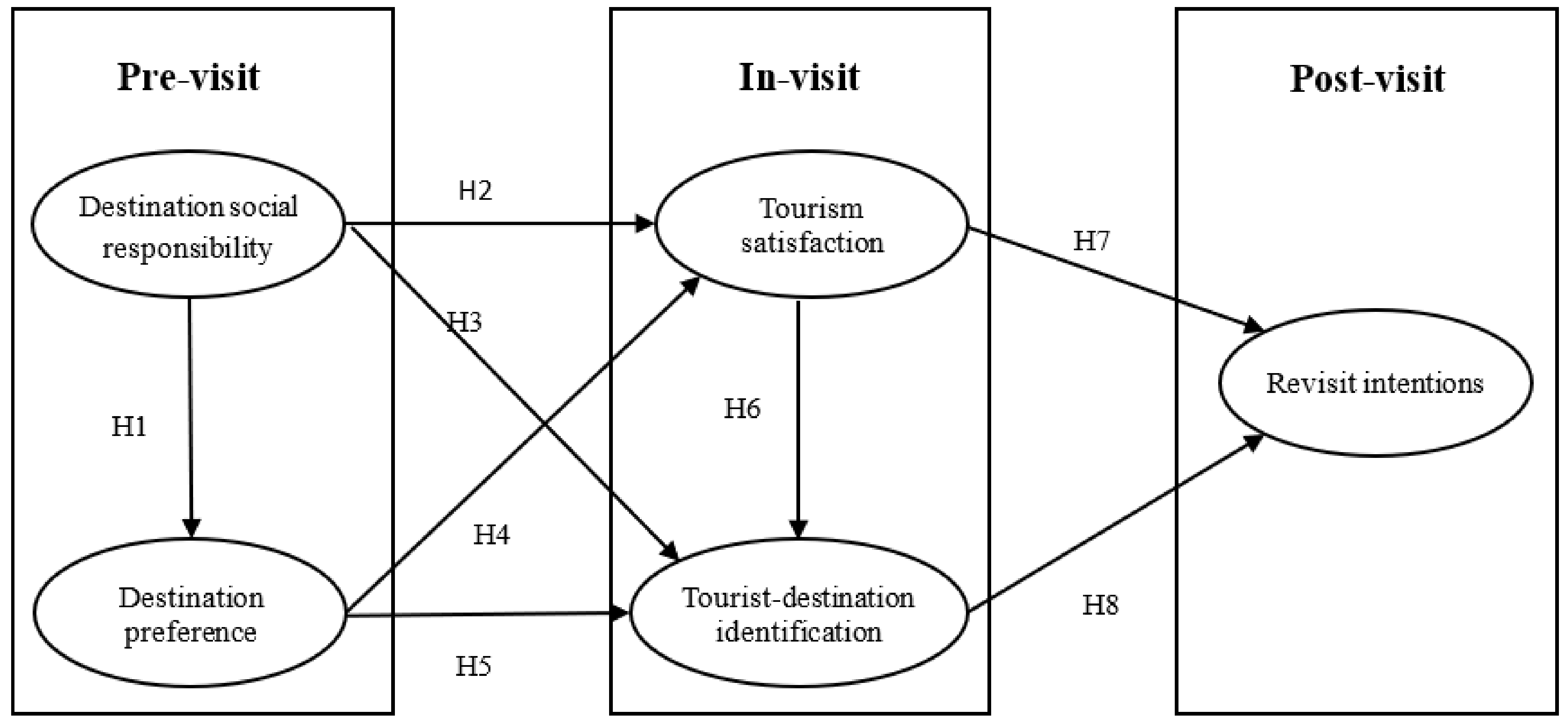

2.5. Hypotheses Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Construct Measurement

3.2. Pre-Test of the Measurements

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis Method

3.5. Sample Description

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Common-Method Bias Test

4.2. Multivariate Normality Test

4.3. Measurement Model

4.3.1. The Indices of the Measurement Model

4.3.2. Reliability Testing

4.3.3. Validity Testing

4.4. Structural Model

4.4.1. Structural Model Fitting Indices

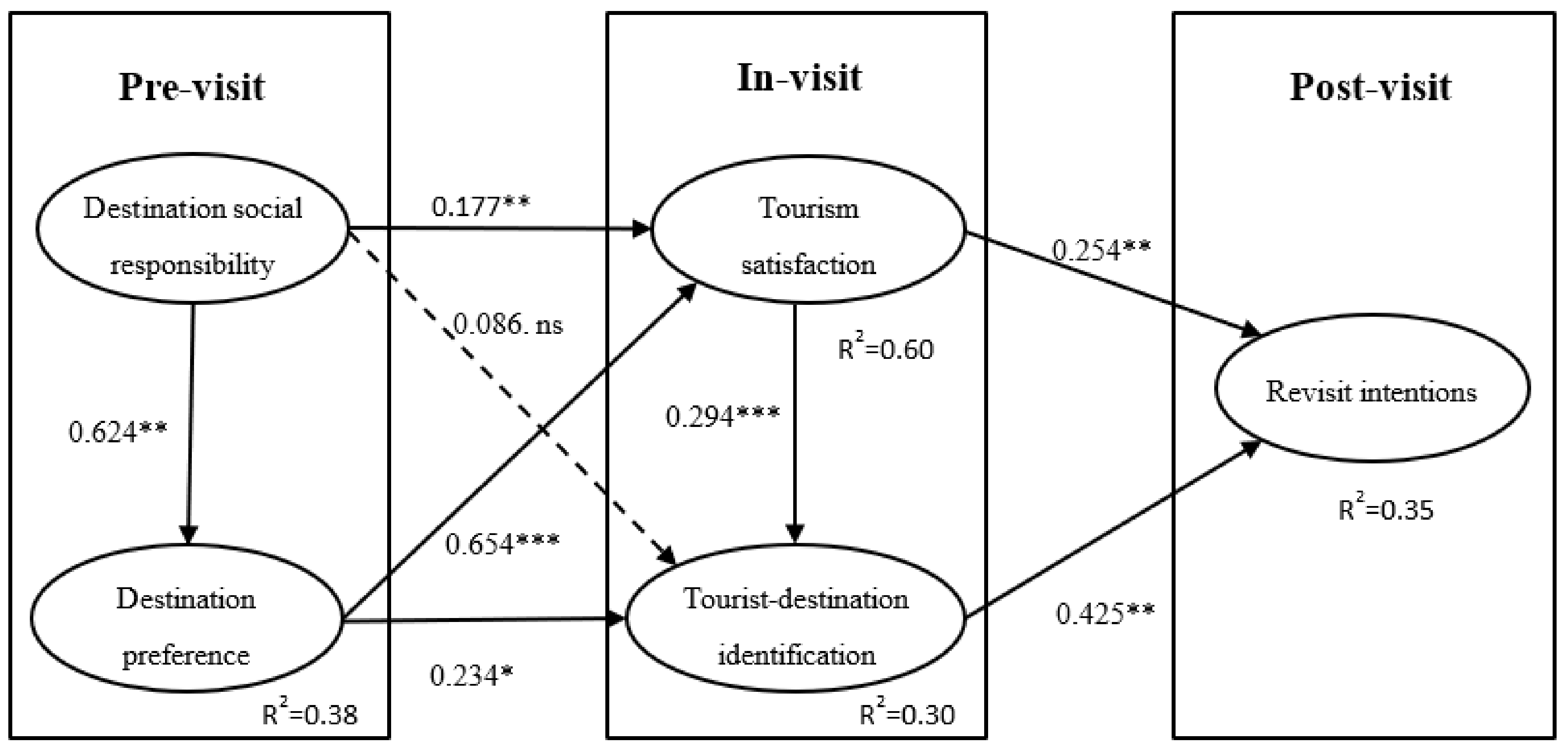

4.4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.4.3. The Explanation of the Model

4.5. Mediating Effect Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Lee, J. Support of marijuana tourism in Colorado: A residents’ perspective using social exchange theory. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 320–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Lai, F.; Wang, Y. Understanding the relationship of quality, value, equity, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions among golf travelers. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.Y.; Zhang, H.Q. Structural relationships among destination preference, satisfaction and loyalty in Chinese tourists to Australia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Hsu, M.R. Service fairness, consumption emotions, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The experience of Chinese heritage tourists. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 786–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The effect of destination social responsibility on tourist environmentally responsible behavior: Compared analysis of first-time and repeat tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Shi, G.; Chu, R. The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and perceived brand quality on customer-based brand preference. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.A. Coupon response in services. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Cha, Y. Antecedents and consequences of relationship quality in hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 21, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F.; Sasser, W.E. Zero defections: Quality comes to services. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Elliott, K.M. Predictors of relationship quality for luxury restaurants. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.A.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The effect of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; del Bosque, I.R. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S. How companies’ good deeds encourage consumers to adopt pro-social behavior. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Grønhaug, K. The role of moral emotions and individual differences in consumer responses to corporate green and non-green actions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 333–356. [Google Scholar]

- Huntley, J.K. Conceptualization and measurement of relationship quality: Linking relationship quality to actual sales and recommendation intention. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of destination social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceived quality of life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Seo, K.; Sharma, A. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the airline industry: The moderating role of oil prices. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Hsu, M.; Chen, X. How does perceived corporate social responsibility contribute to green consumer behavior of Chinese tourists: A hotel context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3157–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, Y. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder value of restaurant firms. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Hwang, Y.; Yu, C.; Yoo, S. The Effect of Destination Social Responsibility on Tourists’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, R.; Ghoneim, A.; Irani, Z.; Fan, Y. A brand preference and repurchase intention model: The role of consumer experience. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 1230–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S. Relationships between preference and purchase of brands. J. Mark. 1950, 15, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Lysonski, S. A general model of traveler destination choice. J. Travel Res. 1989, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, F.; Hsu, M.K.; Chang, F. Determinants and outcomes of relationship quality: An empirical investigation on the Chinese travel industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 14, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.; Makens, J. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 350–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolis, C.; Weitz, B.A. Relationship quality and buyer-seller interactions in channels of distribution. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 46, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch, M.J.; Swanson, S.R.; Kelly, S.W. The role of relationship quality in the stratification of vendors as perceived by customers. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J.E.; Combs, L.J. Product performance and consumer satisfaction: A new concept. J. Mark. 1976, 40, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. User satisfaction and product development in urban tourism. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction process in retail setting. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1985; pp. 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamu, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-categorization, affective commitment, and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma matter: A partial test of the reformulated model of organization identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. To be or not to be: Central questions in organizational identification. In Identity in Organizations: Building Theory Through Conversations; Whetten, D.A., Godfrey, P.C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, C.; Singh, J. Curvilinear effects of consumer loyalty determinants in relational exchanges. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.A.; Sheth, J.N. The Theory of Buyer Behavior; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, O.; Levav, J. Choice construction versus preference construction: The instability of preferences learned in context. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Weaver, P.A. Customer-based brand equity for a destination: The effect of destination image on preference for products associated with a destination brand. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. The adolescence of institutional theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1987, 32, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Ferrell, L. A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daub, C.-H.; Ergenzinger, R. Enabling sustainable management through a new multi-disciplinary concept of customer satisfaction. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks Cole: Monterrey, Mexico, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, A.; del Bosque, I.R. Sustainable development and stakeholder relations management: Exploring sustainability reporting in the hospitality industry from a SD-SRM approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Bagozzi, R.P. Explaining consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of gratitude and altruistic values. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; del Bosque, I.R. An integrative framework to understand how CSR affects customer loyalty through identification, emotions and satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Lane, V.R. A stakeholder approach to organizational identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matute, J.; Bravo, R.; Pina, J.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility and price fairness on customer behavior: Evidence from the financial sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.K. Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behaviour? The mediating roles of customer-company identification and affective commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Al-Marri, M. Exploring the effect of self-image congruence and brand preference on satisfaction: The role of expertise. J. Mark. Manag. 2007, 23, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakra, R. Relationship between communication satisfaction and organizational identification: An empirical study. J. Bus. Perspect. 2006, 10, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, G.; Bernache-Assollant, B. Consumer loyalty in sport spectatorship services: The relationship with consumer satisfaction and team identification. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; German, S.D.; Hunt, S.D. The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Lin, C.; Morais Duarte, B. Antecedent of attachment to a cultural tourism destination: The case of hakka and non-hakka Taiwanese visitors to pei-pu, Taiwan. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Skarmeas, D.; Oghazi, P.; Beheshti, H.M. Achieving tourist loyalty through destination personality, satisfaction, and identification. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2227–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wulf, K.; Odekerken-Schroder, G.; Iacobucci, D. Investments in consumer relationships: A cross-country and cross-industry exploration. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, R.W.; Dant, R.P.; Grewal, D.; Evans, K.P. Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. The roles of quality, value, and satisfaction in predicting cruise passengers’ behavioral intentions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 24, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Kastenholz, E. Corporate reputation, satisfaction, delight, and loyalty towards rural lodging units in Portugal. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shouk, M.A.; Zoair, N.; EI-Barbary, M.N.; Hewedi, M.M. The sense of place relationship with tourist satisfaction and intentional revisit: Evidence from Egypt. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Li, Y.; Harris, L. Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identify salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; García de los Salmones, M.M.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. The effect of corporate associations on consumer behavior. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 47, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Hogg, M.A.; Oakes, P.J.; Reicher, S.D.; Wetherell, M.S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Kaushik, A.K. Destination brand experience and visitor behavior: The mediating role of destination brand identification. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bloom, J.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Taris, T.W.; Sonnentag, S.; de Weerth, C.; Kompier, M.A.J. Effects of vacation from work on health and wellbeing: Lots of fun, quickly gone. Work Stress Int. J. Work Health Organ. 2010, 24, 196–216. [Google Scholar]

- De Bloom, J.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Sonnentag, S.; Taris, T.W.; de Weerth, C.; Kompier, M.A.J. How does a vacation from work affect employee health and well-being? Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1606–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery, well-being, and performance-related outcomes: The role of workload and vacation experiences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Abdullah, J. Holiday taking and the sense of well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 13, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Pearce, J. How does destination social responsibility contribute to environmentally responsible behaviour? A destination resident perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.T.; Cowles, D.L.; Tuten, T.L. Service recovery: Its value and limitations as a retail strategy. International J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1996, 7, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Hsu, M.K.; Swanson, S. The effect of tourist relationship perception on destination loyalty at a world heritage site in China: The mediating role of overall destination satisfaction and trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 180–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Benter, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Hu, D.; Swanson, S.R.; Su, L.; Chen, X. Destination perceptions, relationship quality, and tourist environmentally responsible behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Monthly Income | ||||

| 18 to 24 | 183 | 35.1 | Less than 2000 RMB | 211 | 40.4 |

| 25 to 44 | 166 | 31.8 | 2000 to 2999 RMB | 52 | 10.0 |

| 45 to 64 | 116 | 22.2 | 3000 to 3999 RMB | 89 | 17.0 |

| 65 or Older | 57 | 10.9 | 4000 to 4999 RMB | 65 | 12.5 |

| 5000 RMB or More | 105 | 20.1 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 274 | 52.5 | |||

| Female | 248 | 47.5 | |||

| Visiting times | |||||

| Education | First Time | 205 | 39.3 | ||

| Less than High School | 34 | 6.5 | Two Times | 52 | 10.0 |

| High School/Technical School | 91 | 17.4 | Three Times | 50 | 9.6 |

| Undergraduate/Associate Degree | 345 | 66.1 | Four Times | 46 | 8.8 |

| Postgraduate Degree | 52 | 10.0 | Five Times or More | 169 | 32.4 |

| Construct | Items | Mean | Standard Deviation | Standard Loading | T-Statistic | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination social responsibility | The destination management organization and service providers of Yuelu Mountain are environmentally responsible | 5.60 | 1.265 | 0.775 | 20.225 | 0.880 | 0.600 | 0.881 |

| The destination management organization and service providers of Yuelu Mountain give back to the local community | 5.49 | 1.287 | 0.816 | 21.812 | ||||

| The destination management organization and service providers of Yuelu Mountain are successful in generating and allocating their tourism revenues | 5.46 | 1.262 | 0.674 | 16.691 | ||||

| The destination management organization and service providers of Yuelu Mountain treat their stakeholders well | 5.51 | 1.285 | 0.802 | 21.271 | ||||

| The destination management organization and service providers of Yuelu Mountain act ethically and obey all legal obligations to fulfill their social responsibilities | 5.75 | 1.242 | 0.797 | 21.090 | ||||

| Destination preference | Yuelu Mountain would easily be my first choice for a journey | 5.46 | 1.178 | 0.792 | 20.875 | 0.874 | 0.634 | 0.873 |

| Yuelu Mountain is more attractive than any other destination | 5.07 | 1.348 | 0.802 | 21.265 | ||||

| I am more interested in visiting Yuelu Mountain than other destinations | 5.43 | 1.214 | 0.818 | 21.902 | ||||

| I still intend to visit Yuelu Mountain, even if other destinations offer a better tourism experience | 5.29 | 1.306 | 0.775 | 20.237 | ||||

| Tourist satisfaction | Overall, I was satisfied with my visit to Yuelu Mountain | 5.47 | 1.295 | 0.878 | 25.030 | 0.926 | 0.898 | 0.925 |

| Compared to my expectations, I was satisfied with my visit to Yuelu Mountain | 5.34 | 1.245 | 0.911 | 26.582 | ||||

| Compared to an ideal situation, I was satisfied with my visit to Yuelu Mountain | 5.31 | 1.314 | 0.904 | 26.242 | ||||

| Tourist-destination identification | I am very interested in what others think about Yuelu Mountain | 4.85 | 1.442 | 0.793 | 21.321 | 0.921 | 0.744 | 0.919 |

| Yuelu Mountain’s success is my success | 4.63 | 1.434 | 0.884 | 25.236 | ||||

| When someone says positive things about Yuelu Mountain, it feels like a compliment to myself | 4.78 | 1.535 | 0.900 | 26.016 | ||||

| When someone criticizes Yuelu Mountain, I would feel embarrassed | 4.84 | 1.457 | 0.869 | 24.585 | ||||

| Revisit intentions | I intend to revisit Yuelu the destination again | 5.39 | 1.477 | 0.793 | 21.586 | 0.931 | 0.819 | 0.926 |

| It is very likely that I will revisit the destination in the future | 5.05 | 1.566 | 0.981 | 30.449 | ||||

| The likelihood of my return to the destination for another travel is high | 5.02 | 1.614 | 0.931 | 27.741 | ||||

| Goodness-of-fit | = 2.486, RMSEA = 0.060, GFI = 0.927, AGFI = 0.902, NFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.959, CFI = 0.966 | |||||||

| Destination Social Responsibility | Destination Preference | Tourist Satisfaction | Tourist-destination Identification | Revisit Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination social responsibility | 0.774 | ||||

| Destination preference | 0.624 | 0.796 | |||

| Tourist satisfaction | 0.584 | 0.762 | 0.898 | ||

| Tourist-destination identification | 0.403 | 0.508 | 0.523 | 0.863 | |

| Revisit intentions | 0.343 | 0.499 | 0.467 | 0.555 | 0.905 |

| Hypothesis | Relationships Between Variables | Label of Path | Standard Path Loadings | T-Value | Standard Error | Hypothesis Test Outcome(Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | Destination social responsibility → Destination preference | λ21 | 0.624*** | 12.689 | 0.046 | YES |

| Hypothesis 2 | Destination social responsibility → Tourist satisfaction | λ31 | 0.177*** | 3.724 | 0.056 | YES |

| Hypothesis 3 | Destination social responsibility → Tourist-destination identification | λ41 | 0.086 | 1.498 | 0.065 | NO |

| Hypothesis 4 | Destination preference → Tourist satisfaction | β32 | 0.654*** | 12.182 | 0.068 | YES |

| Hypothesis 5 | Destination preference → Tourist-destination identification | β42 | 0.234** | 2.966 | 0.096 | YES |

| Hypothesis 6 | Tourist satisfaction → Tourist-destination identification | β43 | 0.294*** | 4.025 | 0.069 | YES |

| Hypothesis 7 | Tourism satisfaction → Revisit intentions | β53 | 0.254*** | 5.451 | 0.046 | YES |

| Hypothesis 8 | Tourist-destination identification → Revisit intentions | β54 | 0.425*** | 8.507 | 0.052 | YES |

| Paths | Indirect Effects | Lower Bound 95% BC | Upper Bound 95% BC |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSR → TS → RI | 0.0450 | 0.0018 | 0.1229 |

| DSR→ TI→ RI | 0.0366 | −0.0095 | 0.1037 |

| DSR → DP→ TS → RI | 0.1037 | 0.0369 | 0.2105 |

| DSR → DP→ TI → RI | 0.0621 | 0.0145 | 0.1503 |

| DSR → DP→ TS → TI → RI | 0.0510 | 0.0113 | 0.1306 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, L.; Huang, Y. How does Perceived Destination Social Responsibility Impact Revisit Intentions: The Mediating Roles of Destination Preference and Relationship Quality. Sustainability 2019, 11, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010133

Su L, Huang Y. How does Perceived Destination Social Responsibility Impact Revisit Intentions: The Mediating Roles of Destination Preference and Relationship Quality. Sustainability. 2019; 11(1):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010133

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Lujun, and Yinghua Huang. 2019. "How does Perceived Destination Social Responsibility Impact Revisit Intentions: The Mediating Roles of Destination Preference and Relationship Quality" Sustainability 11, no. 1: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010133

APA StyleSu, L., & Huang, Y. (2019). How does Perceived Destination Social Responsibility Impact Revisit Intentions: The Mediating Roles of Destination Preference and Relationship Quality. Sustainability, 11(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010133