The 2001–2017 Façade Renovations of Jongno Roadside Commercial Buildings Built in the 1950s–60s: Sustainability of Ordinary Architecture within Regionality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Purpose

1.2. Research Target and Methodology

2. Regionality, Sustainability, and Ordinary Architecture

2.1. Regionality and Sustainability

2.2. Regionality and Sustainability of Ordinary Architecture

3. The History of Jongno, Its Function and Symbolism as a City Center, and the Regional Economy

3.1. History of Jongno

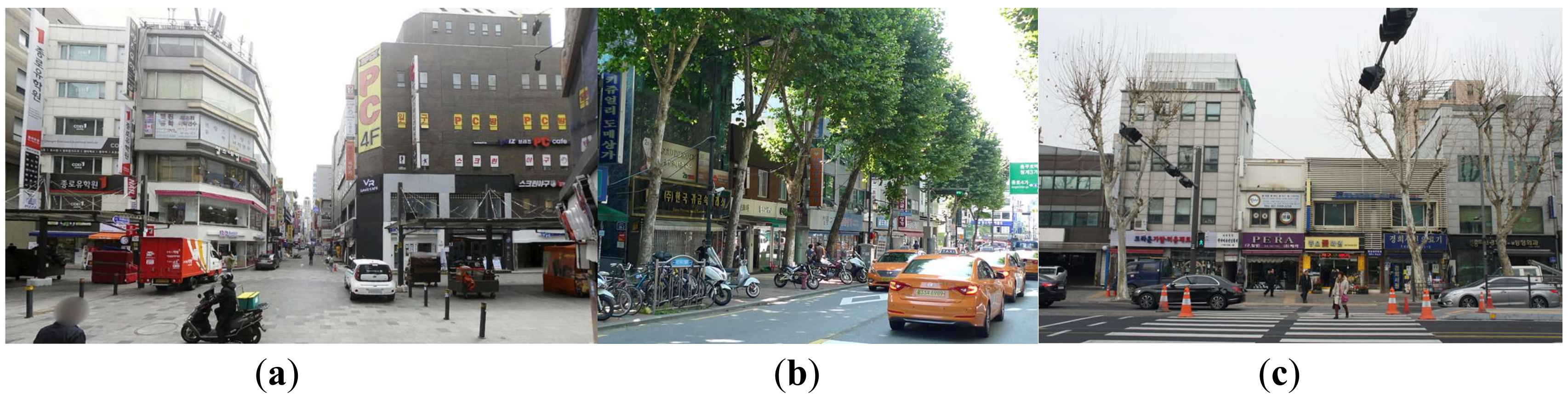

3.2. Current Commercial Regions of Jongno, and Others

4. Formal Analysis of Façade Renovation

4.1. Locational Distribution of and Stores Occupying the Example Structures

4.2. Type Analysis of Façade Renovation

5. Adaptation of Jongno’s Roadside Commercial Buildings and Their Sustainability as City Architecture

5.1. Adaptation to Changing Times and Sustainability as Urban Architecture

5.2. Heritage Value of Roadside Commercial Buildings in Regionality and Sustainability

- (1)

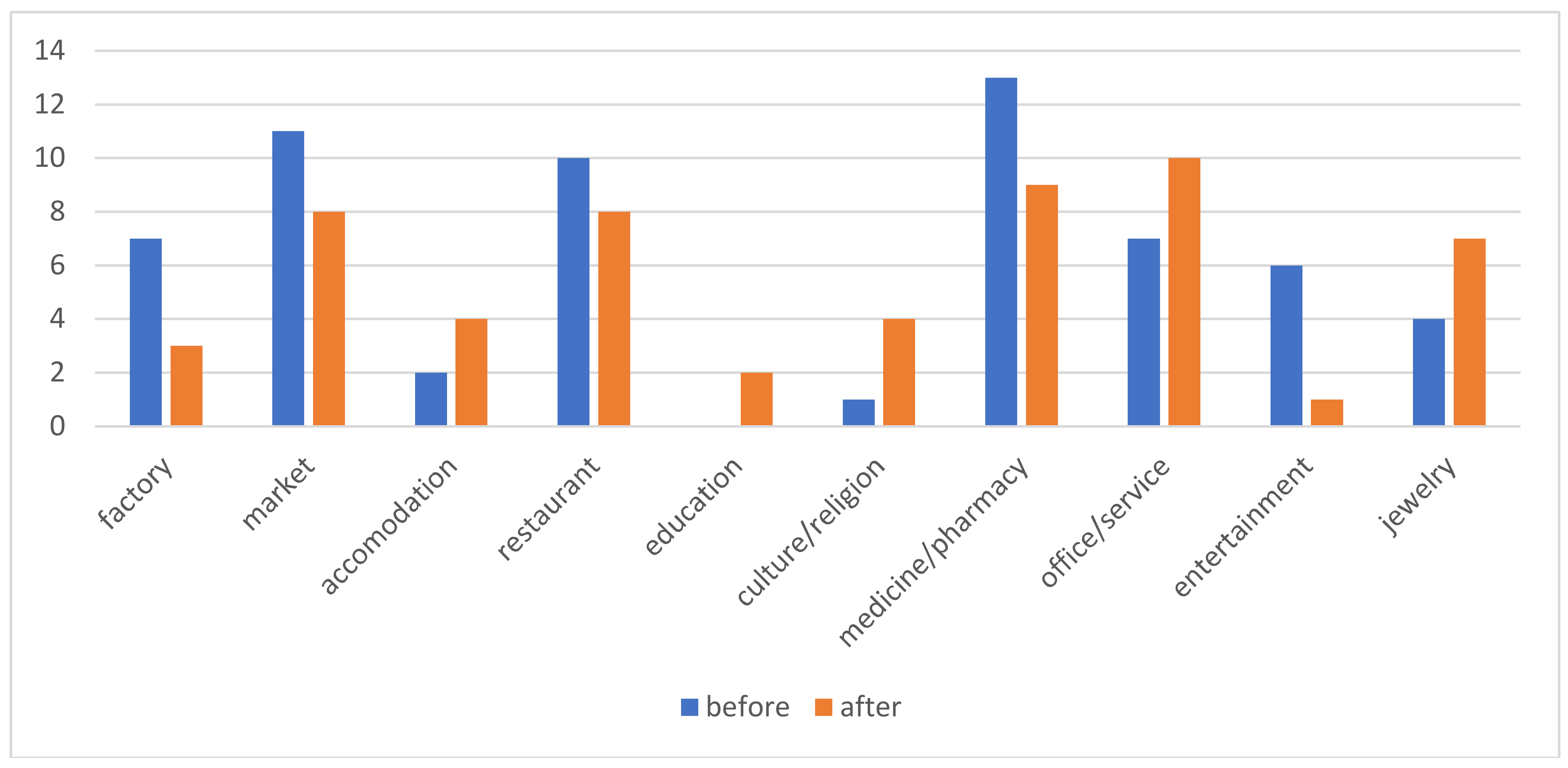

- In commercial areas, the medical industry, jewelry industry, distribution industry, service industry, light industry, and entertainment industry have remained, in high concentration. Table 1 shows that the buildings operate with the same industries occupying the space as were there before renovation, or similar new industries matching the regional commercial area. Furthermore, in many cases, the same businesses occupy the space before and after renovation. This historical regionality also appears in the flow of commercial areas. Within the scope of the research subjects, as shown in Table 1, they continue to inherit the characteristic of segmented areas. Therefore, commercial areas are a factor in maintaining historical regionality. From a heritage perspective, commercial areas inherit their flow from the 1950s–60s period, and can be essentially traced back to the Hanyang era. From a city structure perspective, regionality has been maintained for over 600 years, and façade renovation is an expression of this trend.

- (2)

- The trends in façade renovation show 12 cases in which the renovated façade was completely different from the original, 15 cases in which it was partly different, and 14 cases in which it was similar. Together, a total of 29 cases were similar or only partly different, confirming that renovation was largely influenced by the previous façade plan. This evidence shows that renovations sufficiently maintain historic regionality in roadside commercial buildings that require some updating in response to commercial trends.

- (3)

- Twelve building façades renovated to be completely different from the original can be identified as having attempted to change to fit the current situation. This results in a partial change in the entire Jongno region. Therefore, the heritage value of Jongno’s historical regionality can be identified as “age value,” as defined by Riegl or ”mutable,” as defined by Marta de la Torre [10]. That is, the slow change of the region itself can be viewed as its heritage, and maintenance of the region’s sustainability is thus an advantage. In another light, façades renovated to be completely different suggest a future direction for Jongno’s regionality by adding new symbolism of the contemporary situation. Rather than “pure” heritage value, which emphasizes historicity, this heritage value searches for methods of sustainability while adapting to the present.

- (4)

- The Jongno region is an old city center with a history full of various heritage factors. The recent trend of discovering the value of cultural heritage can be seen as a countermeasure against the decline of old city centers into economic slums. The cultural heritage value of a region as a whole does not needs to freeze at a certain point in time. Traces of eras in the region’s history can be called cultural heritage.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yung, E.H.K.; Langston, C.; Chan, E.H.W. Adaptive reuse of traditional Chinese shophouses in urban renewal project in Hong Kong. Cities 2014, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-H. A Street Regeneration Plan for Small and Medium-sized Cities, Utilizing Historic and Cultural Heritage—Focused on the Modern Buildings of Chung-Ang Street in Ganggyeong, Nonsan. J. Urban Des. Inst. Korea Urban Des. 2013, 14, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jae-Young, L.E.E. Modern Forms of Ordinary Architecture in Seoul’s Jongno District in the 1950–60s and Their Significance. Korea J. 2017, 57, 90–127. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 108. ISBN 9781438432762. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. GENIUS LOCI: Paysage Ambiance Architecture; Pierre Mardaga Editeur: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1981; pp. 5–8. ISBN 2870091478. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. Consideration on authenticity and integrity in world heritage context. City Time 2006, 2, 1–16. Available online: http://www.ct.ceci-br.org (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Auclair, E.; Fairclough, G. Living between past and future, An introduction to heritage and cultural sustainabilty. In Theory and Practice in Heritage and Sustainability between past and Future; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, É. Identification d’une Ville: Architectures de Paris; Picard: Paris, France, 2002; p. 15. ISBN 290751377X. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, R.; Brown, D.S.; Izenour, S. Learning from Las Vegas; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, A. Moderne Denkmalkultus: Sein Wesen Und Seine Entstehung; Braumüller, W., Ed.; BiblioBazaar: Charleston, SC, USA, 1903; ISBN 9781359865304. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation. Herit. Soc. 2013, 6, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, W.-Y. Commercial Quarters and Merchants in Modern Jongno Street. In Jongno; Time, Place, Person—The Study of Seoul’s History in 20th Century; The Institute of Seoul Studies: Seoul, Korea, 2002; pp. 131–135. ISBN 9985831380. [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, P.; Choay, F. Dictionnaire de L’urbanisme et de L’aménagement, 2nd ed.; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2009; p. 154. ISBN 9782130570288. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, G.-B. The Change of Economic Landscape in Jongno—From commercial Economy to Symbolic Economy. In Jongno; Time, Place, Persons—The Study of Seoul’s History in 20th Century; The Institute of Seoul Studies: Seoul, Korea, 2002; pp. 211–219. ISBN 9985831380. [Google Scholar]

| Region | No. of Buildings | Before Façade Renovation | Currently (after Façade Renovation) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jongno 5-ga | 11 | Pharmacy, employment office, oriental medicine hospital, shoe store, golf store, bar, sewing machine store, sewing services, mountain climbing equipment | Hospital, hair salon, car dealership, medical equipment store, flower shop, accounting firm, pharmacy, employment office, café, private educational academy, tent wholesaler, etc. | Many medical businesses and stores related to clothing, such as clothing wholesalers |

| Gwanchul-dong | 4 | Pharmacy, overseas study agent, inn, restaurant, supermarket, pool hall, coffee shop, clothing store, café, video room | Overseas study agent, nail salon, inn, restaurant, supermarket | Many entertainment service businesses, such as inns and overseas studies agents |

| Jongno 2-ga | 4 | Hearing aid seller, glasses store, restaurant, hospital, karaoke, video room, clothing store, coffee shop | Jewelry store, hearing aid store, gym, café, nail salon, music academy | Many hearing aid stores, medical businesses, jewelry stores, and entertainment services |

| Jongno 3-ga | 2 | Restaurant, employment office, gym, hospital | Jewelry store, employment office, realtor | Many jewelry stores and employment offices |

| Myo-dong | 3 | Restaurant, overseas study agent, photography goods, measuring instruments store, acupuncture clinic | Jewelry store, convenience store, restaurant, hospital | Many jewelry stores |

| Waryong-dong | 2 | Supermarket, coffee shop, textbook store, photography goods | Supermarket, café, hostel, restaurant, mounter, Korean traditional clothing store | Many antique arts, traditional Korean clothing, and service industry stores |

| Gwanhun-dong | 3 | Oriental medicine hospital, inn, medical equipment, restaurant, book store | Motel, handicraft gallery, antiques store, antique book store, café | Many antique book, antique, service industry, and medical industry stores |

| Shinmunno 1-ga | 3 | Restaurant, hospital, pharmacy | Restaurant, clothing store, pharmacy, hospital | Many medical industry entities, such as hospitals and pharmacies |

| Jangsa-dong | 2 | Machine seller, electronics store | Machine seller, electronics store | Many stores in the machinery and electronics field |

| Hyoje-dong | 2 | Oriental medicine hospital, dentist, office, employment office | Oriental medicine hospital, dentist, office, realtor, service industry | Many small-scale offices in the medical field |

| Other | 5 |

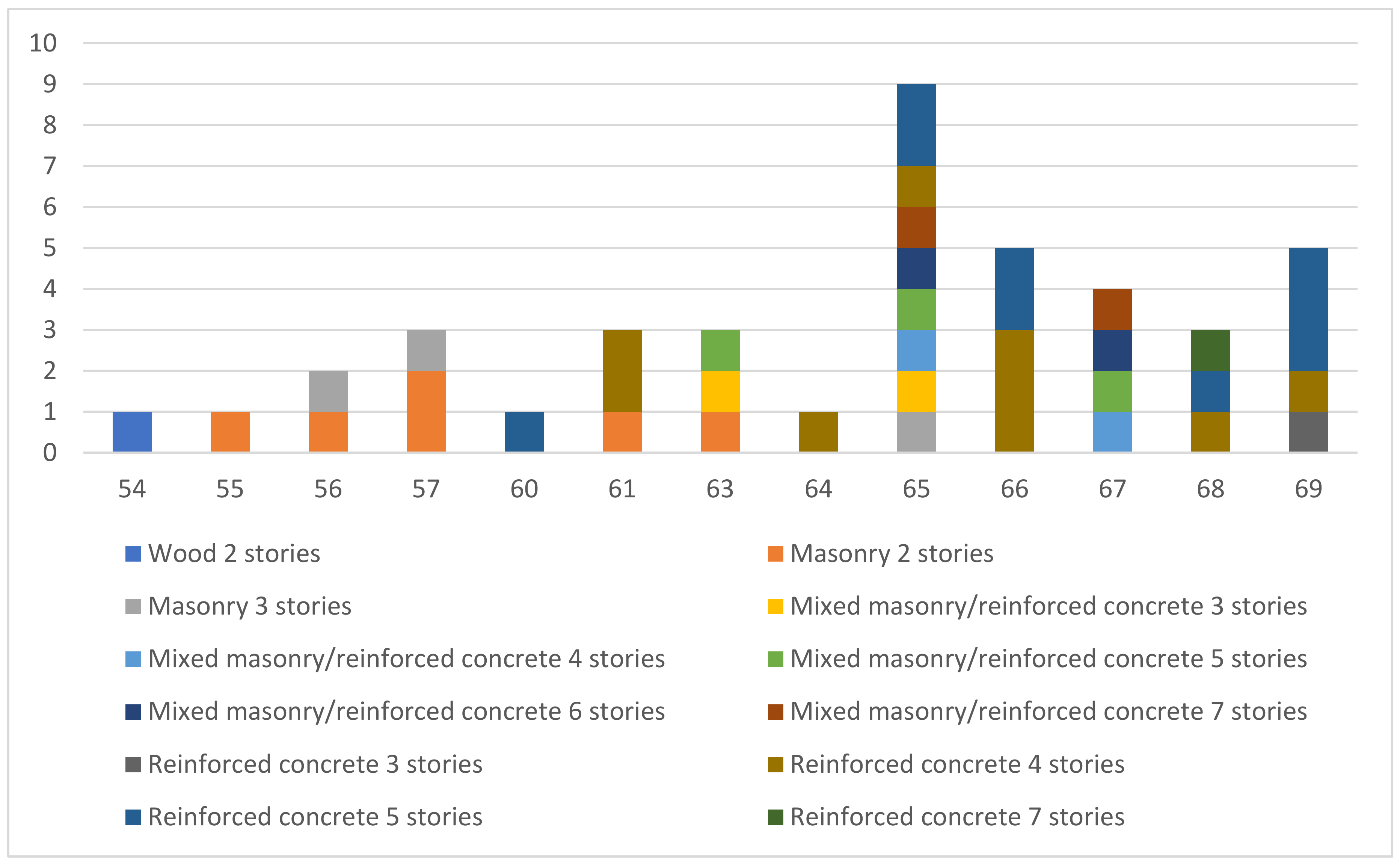

| Structure | No. of Floors | ‘54 | ‘55 | ‘56 | ‘57 | ‘60 | ‘61 | ‘63 | ‘64 | ‘65 | ‘66 | ‘67 | ‘68 | ‘69 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Masonry | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Mixed masonry/reinforced concrete | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Reinforced concrete | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 9 | |||||||||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 41 |

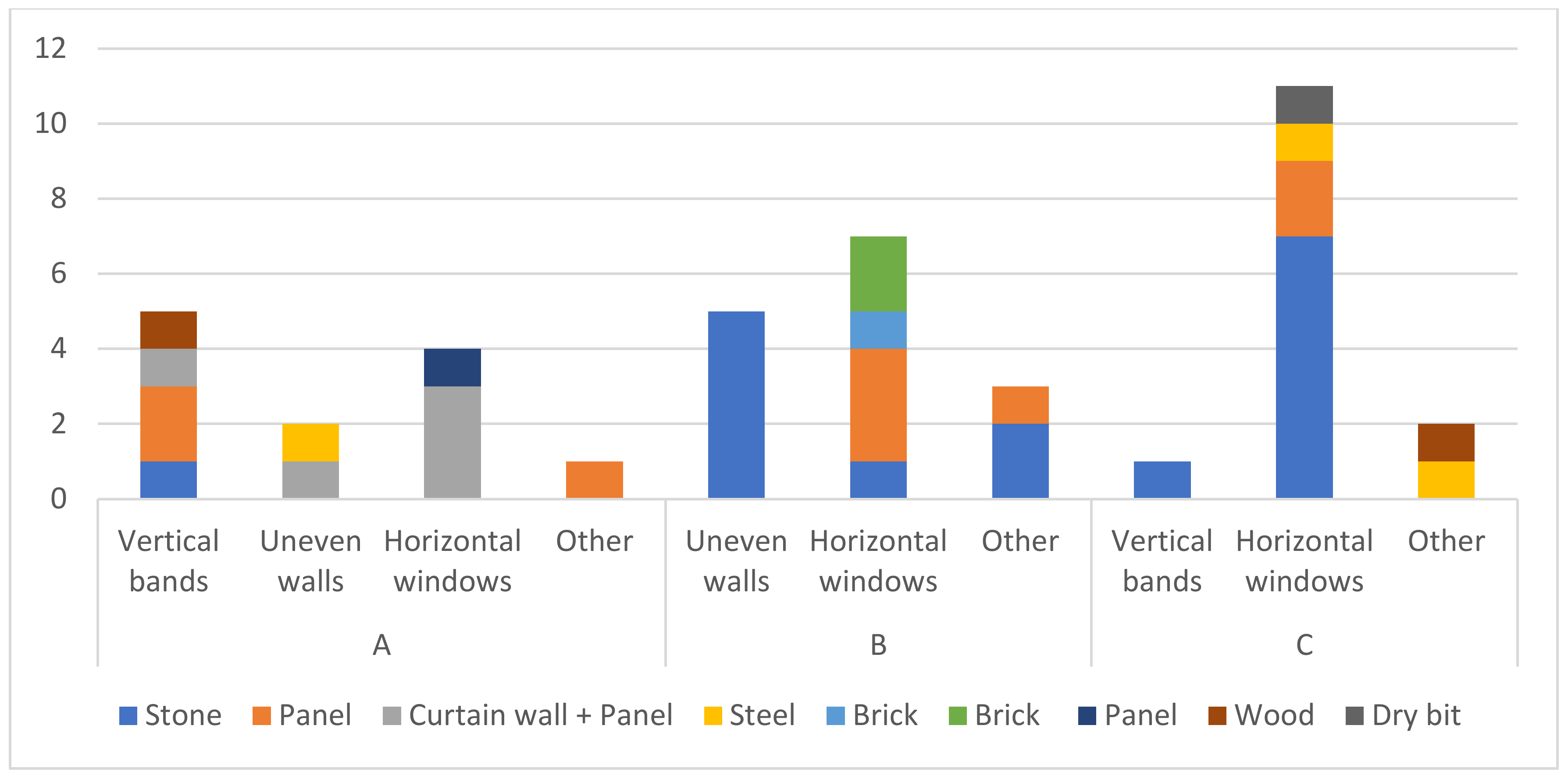

| Façade Renovation Type | New Façade Material | Stone | Panel | Curtain Wall + Panel | Steel | Brick | Brick + Panel | Panel + Wood | Wood | Dry Vit | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Façade Design | ||||||||||||

| A | Vertical bands | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||||||

| Uneven walls | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Horizontal windows | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| B | Uneven walls | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| Horizontal windows | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |||||||

| Other | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||

| C | Vertical bands | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Horizontal windows | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |||||||

| Other | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||

| Total | 17 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 41 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, D.W.; LEE, J.-Y. The 2001–2017 Façade Renovations of Jongno Roadside Commercial Buildings Built in the 1950s–60s: Sustainability of Ordinary Architecture within Regionality. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093261

An DW, LEE J-Y. The 2001–2017 Façade Renovations of Jongno Roadside Commercial Buildings Built in the 1950s–60s: Sustainability of Ordinary Architecture within Regionality. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093261

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Dai Whan, and Jae-Young LEE. 2018. "The 2001–2017 Façade Renovations of Jongno Roadside Commercial Buildings Built in the 1950s–60s: Sustainability of Ordinary Architecture within Regionality" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093261

APA StyleAn, D. W., & LEE, J.-Y. (2018). The 2001–2017 Façade Renovations of Jongno Roadside Commercial Buildings Built in the 1950s–60s: Sustainability of Ordinary Architecture within Regionality. Sustainability, 10(9), 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093261