Abstract

A large body of research supports the idea of social norms communication promoting pro-social and pro-environmental behaviour. This paper investigates social norms communication in the field. Signs prompting consumers about sustainable seafood labels and informing them about other consumers’ sustainable choices were displayed in supermarkets in Norway and Germany. Seafood sales (sustainably labelled versus unlabelled products) were observed before, during, and after the implementation of the signs. The expected change towards more sustainable choices was generally not found. In Norway, the choice of sustainable seafood increased in the prompt-only condition, but the effect was neutralised when social norms information was added. In Germany, social norm messages lead to a decline in sustainable choices compared to baseline, a boomerang effect. Overall, an increase in the purchase of seafood (both sustainably labelled and unlabelled) was noted during the intervention. A second study was carried out to further explore the finding that consumers were mainly primed with “seafood” as a food group. In a laboratory setting, participants were confronted with stereotypical food pictures, combined with short sentences encouraging different consumption patterns. Subsequently, they were asked to choose food products in a virtual shop. Confirming the findings of Study 1, participants chose more of the groceries belonging to the food group they were primed with. These studies suggest that social norms interventions—recently often perceived as “the Holy Grail” for behaviour change—are not as universally applicable as suggested in the literature. According to this study, even descriptive norm messages can produce boomerang effects.

1. Introduction

Modern food consumption goes beyond pure survival. Constant access to large varieties of food from all over the world is considered a default in Western societies. To guarantee modern, affluent lifestyles, enormous amounts of energy and resources are needed [1,2]. Hence, to curtail environmental degradation and secure stable and sufficient food provision in the future, sustainable consumption and production of food must be a global priority [3]. This is, for example, reflected in “Zero Hunger” and “Responsible Consumption and Production” being among United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. However, there is still insufficient policy, and insufficient knowledge, to accomplish these goals on the institutional or individual level.

Consumers’ decisions can be the bottom-up levers for market changes and sustainable development [4,5]. However, we still know too little about the processes steering consumers towards pro-environmental food choices. Despite the common finding that the environment is relevant to them [6,7], consumers often do not translate their pro-environmental attitude into everyday purchase decisions [7,8]. It is therefore important to dig deeper into what motivates consumers to make sustainable choices. A common approach to foster sustainable consumer behaviour is to provide information. These campaigns can result in increased awareness of environmental problems. However, providing information has in itself not proven effective at increasing sustainable choices [9,10]. Various approaches applying the power of social norms give more reason for hope [11]. Instead of relying on humans as rational decision-makers who weigh out pros and cons against each other, social norm approaches make use of the human inclination to spontaneously adapt to others’ behaviour guiding many actions throughout the day.

In this paper, the effectiveness of social norm interventions is explored in a common environment for making everyday consumption choices, the supermarket. The effectiveness of information provision and social norm nudges is tested on sustainable product choices regarding seafood. The expected increase in sustainable seafood purchase was not produced, but instead the interventions led to a general increase in the purchase of seafood. To further explore the mechanisms behind this increase, a second study was conducted to investigate whether the interventions primed food categories, rather than sustainable variants, which was confirmed. The two studies provide new insights into social norm interventions and point towards potential side effects of using social norm interventions in crowded, information-overloaded environments.

1.1. Social Norm Approaches to Promote Pro-Environmental Decision-Making

The social environment is crucial for steering human decision-making. On the negative side, the adaptation to the behaviour of relevant others is part of the cause for many environmental problems because a majority is acting in a way that is harmful to the environment (like car-driving, air travel, meat consumption). On the positive side, however, the same adaptation tendency has the potential to be employed to benefit the environment. That people tend to imitate other people’s behaviour is a well-researched phenomenon [12,13]. Robert Cialdini and his colleagues [14] suggested a Focus Theory of Normative Conduct emphasizing the importance of social norms for environmental decision-making. Two kinds of norms can be distinguished: descriptive norms (what most people do) and injunctive norms (what most people would approve to be the right thing to do). Sometimes, persuasive attempts are only successful when these two types of norms are combined [15,16]. Sometimes the two types of norms pull in different directions (e.g., most people may believe that buying organic food is the right thing to do, but the majority of food sold is still conventional).

The Focus Theory of Normative Conduct is the key theoretical basis for social norms marketing [17,18,19]. This stream of literature initially focused on the correction of common misperceptions regarding undesired behaviours, such as adolescent drinking and smoking. People tend to overestimate the amount of alcohol and cigarettes consumed by peers and therefore engage in these unhealthy behaviours themselves, adapting to a (false) descriptive norm [20,21,22,23,24]. Other approaches employing the power of social norms for promoting pro-environmental behaviour, such as Doug McKenzie-Mohr and colleagues’ Community-Based Social Marketing [25], are especially assumed to play a role for behaviours that are easy to engage in [11]. Last, but not least, social norms are also considered part of people’s “choice architecture” and the communication of social norms a type of “nudging” [26,27]. Nudges are defined as “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any” [28]. Social nudges trigger behavioural adaptation by informing people about the behaviour of relevant others. Nudges do not always include written information, as they might also be manifested in design changes like in-store product placement.

1.2. Social Norms and Consumption Behaviour

Social norms have consistently been found to be predictors of sustainable consumption, such as electricity saving [29] and consumption of organic food [30,31] or of food with a sustainability label [32]. Descriptive norms seem to be a strong and stable predictor of healthy and sustainable consumption, while the impact of injunctive norms seems to be weaker and less consistent [33,34,35]. A positive interaction between descriptive and injunctive norms for sustainable consumption has also been reported [16].

Social norm interventions are typically implemented using signs displaying a normative message [14,34,35]. For example, hotel guests have been asked to reuse their towels by a message written on door hangers [36], park visitors have been invited not to steal petrified wood by signs installed in the park [15], public toilet users have been asked to switch off the light by means of colorful prompts [37], and consumers have been informed about the health food choices of other consumers via signs installed on the shopping basket [35,38]. Social norm interventions are especially powerful for behaviours that are easy to engage in, when they are easily noticeable, understandable, displayed in the moment of action, and formulated in a way that avoids potential “boomerang” effects [11]. Furthermore, social norm communication was found most effective if the social norm message contains not only information about the behaviour of others, but also about similarities between the receiver and the reference group, for example in terms of location and time [14,15,36].

1.3. Concerns about the Application of Social Norm Interventions

Because of the strong evidence of social norms being effective in steering human decisions [14,15,39,40], there is good reason to assume that this effect is manifested in a supermarket setting as well. However, reservations have been voiced about the effectiveness of social norms interventions.

First, there is evidence that some social norms campaigns resulted in “boomerang” effects, increasing the undesired behaviour that the campaign aimed to reduce [15,29]. The potential solution could be not to present descriptive norms information in a way that suggests that the undesired behaviour is common, or presenting it in combination with injunctive norms.

Another reason for caution is that just making an issue more salient may in itself lead to increased engagement in the behaviour the campaign aims to reduce. This is especially likely to happen when the motivation, ability, or opportunity to process information is low, leading to superficial mental processing. For example, studies found an increase in smoking as a result of anti-smoking campaigns [41,42,43] and an increase of junk food consumption after anti-junk-food messages [44,45]. Maybe superficially perceiving cues of cigarettes or junk food without consciously processing the content of the message can work as a mental prime that unconsciously encourages people to smoke or eat unhealthily.

While it is often assumed that the most effective reference groups are majorities [15,29,36], some studies found that minorities can influence people’s behaviour as well. In some cases, small reference groups cause an adaptation to the implicit majority [46]. Sometimes people adapt to a minority, if they identify strongly with this reference group [14,47,48]. Whether the reference group needs to have a certain size to trigger adaptation remains unanswered so far. It is possible that social norms become effective already before a “real majority” is reached when the reference group is relevant [49,50].

A final concern is in regard to the feelings of being observed that people might perceive when performing a certain action. Social norm research claims that with increasing perception of being observed and being responsible, people tend to behave more in line with the social norm [14,51,52,53]. In in-store environments, choices are visible to others and therefore prone to observation. On the other hand, supermarkets are a crowded and anonymous environment in which people make quick choices, which might lead to a diffusion of individual responsibility.

1.4. The Present Research

Despite the mounting evidence on the impact of social norm interventions on a wide range of behaviours, including sustainable consumer choices, little is known about the effect of social norm messaging in cluttered store environments on consumers’ sustainable buying decisions.

Thaler and Sunstein [28] would probably argue that supermarkets are a decision-making context that calls for nudging: the effects are delayed, the choice is difficult because of a large number of products, no feedback is given in the moment of purchase, and the relationship between choice and outcome is ambiguous. Supermarket choice-making is also characterized by high speed and the use of simple choice heuristics. Studies found that people make purchase decisions in less than a second [54] and use simple rules of thumb, like price, taste, and former choices [55]. This hints towards an environment in which peripheral cognitive processing might happen [56].

In this article, the main focus is on the impact of social norm messaging on sustainable consumer choices in the supermarket according to environmental communication guidelines [11,57]. Seafood is chosen as the case in point because marine food resources are an important part of sustainable development. The setup of Study 1 includes the installation of fish-shaped signs in various supermarkets, displaying social norm messages of different intensities to encourage the purchase of seafood carrying a sustainability label. Choosing sustainability-labelled instead of conventional seafood is an operational way for consumers to act more responsibly in this domain [58]. By means of the label, consumers can detect the sustainability-certified options in the store [59]. In-store signs displaying descriptive norms have been found to motivate shoppers to buy more of the displayed product without increasing their total expenses [35]. Payne and Niculescu [35] found that consumption shifted from the consumer’s usual selection towards a higher percentage of fruit and vegetables due to the signs. With this background, it seems reasonable to expect that the display of descriptive norms for sustainable seafood consumption would shift consumption from conventional towards sustainable produce, potentially without changing the overall amount of seafood selected.

The studies were carried out in Norway and Germany, two important seafood markets, characterized by substantially different consumer positions towards sustainable seafood labels. In Norway, sustainable seafood labels are not yet as standard as in many other European countries [60]. Norwegian consumers typically have little knowledge about seafood labels, and many see them as something foreign [61]. As a contrast to this situation, sustainable seafood labelling is relatively popular in Germany. Over 4800 seafood products sold in German supermarket chains are labelled [60]. The concept of sustainable labelling is generally taken up well by German consumers [62]. The total consumption of seafood per capita in Norway (51.1kg) is 2.5 times the European average of 21.9 [63]. German seafood consumption is below the average for European countries with around 12.6 kg per year [63].

Despite these apparent inter-country differences, it is expected that the studied intervention will work equally well in both countries because of its foundation in basic cognitive–behavioural principles. The dependent variable in focus is the relative amount of seafood sold with a sustainability label, compared to seafood without a label. The available data is sales data obtained from participating stores. No contact was made with individual consumers; hence, information on individual consumers was not collected and can therefore not be controlled for.

In Study 2, a priming effect that appears to have an effect in Study 1, presumably due to superficial information processing during grocery shopping, was further explored. Perhaps participants did not fully process the message on the signs installed in the stores in Study 1. Instead, they just activated the food group “seafood” and it worked as a reminder for seafood purchase. To test this possibility, participants in Study 2 were asked to purchase food in a virtual supermarket. Before selecting their products, they were unobtrusively primed with a particular food group. The variable of interest was the amount of food items purchased by food group which participants were primed with before. The food pictures were combined with messages, encouraging different kinds of consumption patterns. It was assumed that, similar to what happened in Study 1, messages would be processed superficially. Therefore, the display of any sign would lead to increased consumption of food belonging to the presented food group, no matter whether the message displayed promoted an increase, decrease, or change of consumption. In the following, both studies will be presented in more detail.

2. Study 1

Signs promoting sustainably labelled seafood via social norm messaging were developed and employed in German and Norwegian supermarkets. Sales volumes were observed under different conditions.

2.1. Hypotheses

The first hypothesis of this study is based on the finding that giving information about a certain issue can in itself influence behaviour [26]. Providing information about sustainable seafood on a fish-shaped sign in the supermarket may in itself be prompt or a “nudge” that increases the likelihood of sustainable seafood consumption [26]. Hence, our first hypothesis is

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Placing a sign with information about sustainable seafood (i.e., a prompt) on the seafood freezer will significantly increase the sale of sustainably labelled seafood products compared to the baseline.

Ölander and Thøgersen [26] argue that the combination of information and a social norms nudge should be even more effective than information or a social norms nudge alone. Thus, if the information about sustainable seafood was extended with social norm information on how many people buy sustainability-labelled seafood, where, and when, a bigger increase in the sale of sustainably labelled seafood should be obtained. However, an important question is how large does the reference group need to be to produce a significant change? It may be assumed that when the reference group is larger than 50%, the sale of sustainability-labelled seafood products should be significantly higher than the baseline or the information-only condition. If the reference group is smaller than 50%, it may be that less labelled seafood would be sold compared to the information-only condition, because participants adapt to the behaviour of the silent majority. Consequently, the second and third hypotheses are

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Adaptation to the obvious majority: Bigger reference groups (>50%) in the social norms message lead to higher sales of labelled products compared to baseline and to a prompt about sustainable seafood only.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Adaptation to the silent majority: Smaller reference groups (<50%) lead to lower sales of labelled products compared to the prompt about sustainable seafood only.

2.2. Materials and Methods

Supermarkets

In Norway, the study was carried out in five medium-sized supermarkets. All stores were located in Trondheim. In Germany, the study was carried out in one medium-sized supermarket and three discounters in Würzburg. In both cases, the supermarkets were located in different parts of the city to cover potential differences between consumers from different neighbourhoods. In each country, one supermarket served as a control condition, which means that no intervention was implemented there.

Products

All participating supermarkets had a section with a sufficient selection of frozen seafood including labelled products and nonlabelled equivalents. Regarding labelling, products certified by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) for wild fish and the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) for farmed fish were selected, each being the most popular certification system in their domain. As many product pairs as possible were identified in each supermarket, resulting in 15 pairs in total of which 5 pairs were in German and 10 pairs were in Norwegian supermarkets. Products of one pair had similar characteristics regarding product type, taxa, price, weight, and packaging. One product in each pair carried an MSC or ASC sustainability label while the other one did not. Hence, it was possible to compare sales of labelled versus nonlabelled products while keeping the other product characteristics constant. Table A1 in Appendix A lists all product pairs and their key characteristics.

Interventions

Signs were placed on the glass cover in the frozen seafood section. The signs themselves were made from thick glossy paper in the colours blue and grey. The form of the signs resembled a fish (see Figure 1). Eight different conditions were created. On all signs, the MSC/ASC seafood label was displayed with a short explanation of its meaning (“The MSC/ASC certification contributes to sustaining marine resources”). This may be considered a prompt, reminding consumers of the label at the point of purchase. The message can also be interpreted as an injunctive norm, implicitly reminding consumers of their responsibility to choose environmentally friendly consumption alternatives. Sign 1 only contained this prompt/injunctive norm and no descriptive norm information. Signs 2–8 displayed an additional text including the reference group size, type, and behaviour (4%, 11%, 28%, 52%, 69%, 82%, or 91% of all customers buying seafood in our shop yesterday chose MSC/ASC) (see Figure 1). Hence, the reference group was defined as close as possible to the receiver regarding time (yesterday), location (same supermarket), and action (seafood purchase).

Figure 1.

28% reference group size sign. Signs 2–8 were identical except for the percentage. On Sign 1, the social norm message was absent.

The text on the signs was in the national language. In Germany, both the MSC and the ASC certifications were indicated on the sign while in Norway only the MSC was mentioned because ASC labelling had not yet been introduced in Norway at that time. The eight conditions were rotated in a randomized order so that the same condition was never applied two days in a row in the same supermarket or at the same day in two different supermarkets in the same city. Sales numbers for the identified products were obtained after completion of the experimental period from the store managers. The period included two weeks before, two weeks during, and two weeks after the implementation of the signs.

2.3. Data Analysis

Sales data for seafood products was used as the dependent measure on two different levels, nested into each other: the supermarkets and product pairs. Multilevel analyses recognize that product purchase in one supermarket systematically varies from purchases in other supermarkets and account for the fact that individual sales data would not provide independent observations. In this two-level analysis, the variation is split into two parts: one part that is constant across products and one part that is constant across supermarkets.

To analyze the data on two embedded levels, a multilevel mixed-effects linear regression analysis was conducted. First, relative sales of labelled versus nonlabelled seafood are regressed on the treatment variable (before, prompt only, 4%, 11%, 28%, 52%, 69%, 82%, 91%, after) and country (Norway, Germany) as well as their interaction. Robust standard errors were applied because full normal distribution of errors could not be ensured. Based on observed tendencies and to increase statistical power, the condition variable was also aggregated into five groups which were (1) before, (2) information only, (3) minority reference group <50%, (4) majority reference group >50%, and (5) after.

2.4. Results

One product pair, Norwegian shrimps, had to be excluded from the analysis as it was only sold once during the whole experimental period, providing no variance. For the analysis there remained N = 3277 valid observations of product sales. Consequently, nine product pairs remained in Norway, and five in Germany. A preliminary look at the dataset revealed that the total number of frozen seafood products within the target categories sold per day per supermarket was significantly and substantially higher in Germany (M = 10.15, SD = 8.52) than in Norway (M = 4.03, SD = 3.69). Therefore, the following analysis focuses on the relative amount of labelled versus unlabelled products sold on each day. Before the intervention, relatively more labelled products than unlabelled products were sold in Norway (Mlabelled = 1.38, SD = 1.90; Munlabelled = 0.74, SD = 1.47) than in Germany (Mlabelled = 3.85, SD = 4.64; Munlabelled = 7.66, SD = 8.29).

The multilevel analysis applying all experimental conditions (Nproduct_pairs = 896) revealed significant (β = 0.30, p < 0.001) inter-country differences with Norwegian supermarkets selling a higher percentage of sustainability-labelled seafood (66.89%) than Germany (33.80%) during the experimental period, same as before. There was no significant effect on the sale of labelled seafood in any of the interventions. Interactions between country and condition were also not significant. Hence, in comparison to the control group or the baseline, there is no indication of any of the signs, irrespective of whether or not descriptive norms were included, or with higher or lower percentage, leading to more labelled seafood sales.

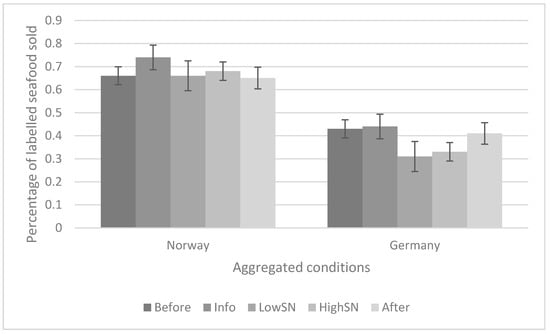

In order to simplify, and because the detailed analysis revealed no differences between different descriptive norms conditions, a new multilevel analysis was done with only five groups (before, prompt, low social norms, high social norms, after). Again, a significant main effect for country was found. This analysis revealed a significant increase of labelled seafood sales in the prompt-only condition in Norway and a significant decrease of labelled seafood sales in the low reference group descriptive norm condition in Germany. A marginally significant decrease was found in the high reference group descriptive norm condition in Germany as well (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Beta coefficients and significance level of both main effects applying single contrasts, Nproductpairs = 896.

Figure 2.

Percentage of sales of labelled seafood in Norway and Germany. Margins of aggregated condition variable applied.

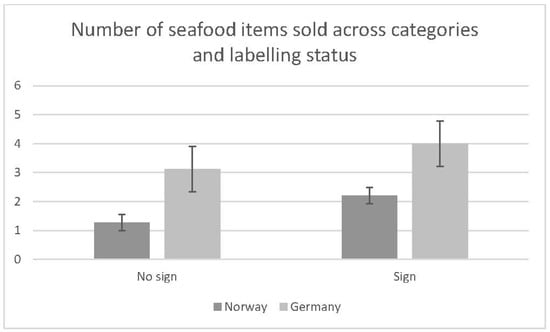

The total amount of studied types of seafood (labelled as well as unlabelled) sold increased significantly by 42% during the experiment (p = 0.01) (see Figure 3), 72% in Norway (p = 0.04) and 29% in Germany (p = 0.11). This further confirms that the interventions actually had an effect.

Figure 3.

Total number of seafood items sold at baseline and during the intervention.

2.5. Discussion

The main strengths of this study are that it was carried out in a field setting, in ordinary supermarkets in two different countries, and with the outcome measure being actual sales data, rather than self-reported behaviour. However, real-life settings are also “messy” and difficult to control, which may lead to unexpected, confounding influences. For example, repeat customers might recognize the signs and notice the strongly differing percentages in the descriptive norm messages. This could lead them to become suspicious and doubt the credibility of the messages and potentially affect their choices. More important is the fact that contextual factors can rarely be controlled in a field experiment. We know that participating supermarkets did not offer special discounts on seafood during the experiment. However, there could be indirect effects of discounts on other products or in other supermarkets, which we could not control. Also, due to data confidentiality issues, only sales numbers for the identified product pairs could be obtained. This leaves unknown how the sales developed of types of seafood products other than those included in the study.

More frozen seafood of the studied types was sold in the German than in the Norwegian supermarkets. This seems to contradict statistics showing that the total amount of seafood consumed in Norway is higher than in Germany [63]. A possible explanation could be that the included German supermarkets are bigger and have more customers than the Norwegian supermarkets. Another reason might be that Norwegian consumers buy relatively more fresh seafood because of the shorter transport distances from catch to counter. Within the frozen seafood category, the number of different sustainability-labelled seafood products was higher in the Norwegian than in German supermarkets and so was their share of the sale within these categories. The higher share of sale in the Norwegian supermarkets might partly be due to the higher number of different labelled products leading to higher exposure to the labels in the Norwegian than in the participating German supermarkets. In addition, the participating supermarkets in Germany were mostly discounters, perhaps attracting consumers who put a stronger emphasis on low prices. In Norway, there is not necessarily a price premium connected to sustainability labelling whereas in Germany the labelled option is always the more expensive option in each pair (see Appendix A). This also suggests fewer barriers for the Norwegian consumers to respond when prompted to buy sustainability-labelled seafood.

The descriptive norm interventions did not have the intended effect on the proportion of sustainability-labelled seafood sold—on the contrary. In Germany, the descriptive norm messages led to a significant fall in the ratio of sustainability-labelled seafood sold, compared with the baseline. Hence, Hypothesis 1 was not confirmed. Further, in Norway, the increase in the proportion of sustainability-labelled seafood being sold that was registered when a prompt about sustainable seafood labels was provided on the counter was neutralized when descriptive norms information was added to the sign.

So, against all the expectations and the mounting evidence supporting the power of descriptive norms, only a negative (boomerang) effect was found for the employed descriptive norm interventions. Hence, hypothesis H2 was also not confirmed. The sign with reference group >50% did not lead to an increase in sales on labelled seafood. The expected negative effect of a <50% reference group (hypothesis H3) was confirmed in both countries compared with the prompt-only condition and also in Germany compared with the baseline. However, irrespective of the size of the reference group, the descriptive norms interventions produced a boomerang effect in this case.

It can hence be concluded that the employed type of descriptive norms communication was not effective at promoting sustainable seafood in these Norwegian and German supermarkets. Since consumers were not interviewed individually, we can only speculate as to why. The relatively strong increase in total sales of the covered types of seafood during the experimental interventions refutes the possibility that the consumers just did not notice the interventions. Consumers increased their general consumption of the covered types of seafood when there was a sign prompting sustainable seafood, with or without social norms information, installed on the frozen fish counter, whereas the proportion of labelled versus unlabelled seafood overall remained stable. Similarly, Payne and Niculescu [35] found a general increase of fruit and vegetable purchase when displaying a message about descriptive norms regarding fruit and vegetable consumption. It seems that the message employed by Payne and Niculescu [35] made the food group “fruit and vegetables” salient and prompted the consumption of fruit and vegetables, and the same in the present study regarding frozen seafood. Frozen seafood consumption was triggered irrespective of the message printed on the signs. Overall, consumers’ processing of the information on the sign seems to have been too shallow to make them change their usual patterns when purchasing seafood. In other words, consumers bought more of what they usually buy as a response to the fish-shaped sign installed on the counter.

After the intervention, the total sale of the covered types of seafood decreased again, back to the level before the intervention. This further suggests that the positive effect produced during the intervention was mainly due to the signs making seafood as a product group more salient.

The apparent insufficient attention to the actual message on the signs could be due to the information provided being too much and presented in too-small-lettered text. As in-store decisions are characterized by time pressure and the use of simple heuristics [55], expecting consumers to read a relatively long text might not be realistic in this type of environment.

This may also partly explain why the sustainable seafood prompt had a stronger positive effect in the Norwegian than in the German supermarkets. In the Norwegian supermarkets, there were on average twice as many sustainability-labelled products and the customers here bought twice as high a proportion of sustainability-labelled seafood products as those in the German supermarkets. This suggests that the sustainability label was already more salient to the participating Norwegian than German consumers, making it likely that they were able to process the prompt more effortlessly.

However, the significant boomerang effect produced by the descriptive norms communication suggests that at least some consumers processed this information. This effect can hardly be explained by the fact that the interventions led to an increase in the total seafood sales. Rather, it suggests that those consumers who processed the descriptive norms information were discouraged by it. Prior research suggests that boomerang effects can result from social norms communication when receivers feel that it is pressing and potentially limits their freedom (i.e., psychological reactance) [64,65]. However, this effect has until now only been reported in connection with injunctive norm communication. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study finding that descriptive norm communication can also produce a boomerang effect, suggesting psychological reactance.

An important question that remains insufficiently answered is the extent to which the text on the sign was processed at all and thereby contributed to the found effects. Did the consumption of seafood as a product group increase because the sustainable label was made more salient, or because the shape of the sign prompted seafood in general? As the answer to this question would make an important difference to the communication of sustainable seafood, this question is investigated in Study 2. Also, individual characteristics of customers and possible interactions between customers could not be controlled in the field experiment. Therefore, it was decided to conduct Study 2 in a more controlled environment: a laboratory setting.

3. Study 2

Study 1 suggests that textual promotion material displayed in a supermarket environment might be only superficially processed, if at all, or at least not in a way that leads to the desired behavioural outcome. The results of Study 1 suggest that only superficial, easily processed characteristics of the message are processed, promoting whatever these characteristics prime—in Study 1, mostly frozen seafood in general. This is in line with what Petty and Cacioppo [56] call the peripheral route to persuasion, which prior research has found leads to a neglect of details, such as negations [66], and which might therefore lead to the opposite of the intended effect, such as an increase in smoking as a result of an anti-smoking campaign [41,42,43]. To empirically verify the suspicion that consumers in cases such as the one studied in Study 1 do not thoroughly and exactly process the provided information, a laboratory study was developed where food primes were combined with messages, pursuing different purposes.

The second study was carried out in a virtual supermarket setting, developed in collaboration with the Vienna Centre for Experimental Economics (https://vcee.univie.ac.at/laboratory/). Prior research has found that virtual reality settings can evoke similar emotional, cognitive, and behavioural reactions in participants in a laboratory experiment as in the field [67].

3.1. Hypotheses

Based on the priming theory, which states that the prior exposure to a stimulus affects the automatic behavioural response to a later stimulus [68,69], the following hypotheses were developed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Consumers being exposed to a sign superficially relating to a specific food category (e.g., seafood or dairy) buy more products from that category than people not being exposed to that prime (e.g., being exposed to a control prime or other food group primes), irrespective of the textual message attached to it.

In more detail and referring to the four different types of messages employed in this study, three additional subhypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Giving consumers information about sustainability labelling in addition to the superficial food group cue does not increase their consumption of sustainability-labelled food items in comparison to consumers receiving other relevant information, for example, about the health benefits or health threats, or receiving no additional information at all.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Similarly, giving consumers information on health benefits of certain foods, in addition to the superficial food group cue, does not increase the consumption of products belonging to this food group in comparison to consumers receiving other relevant information, for example, about sustainability or health threats, or receiving no additional information at all.

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

Finally, giving consumers information on health risks of foods in addition to the superficial food group cue does not decrease the consumption of products belonging to this food group in comparison to consumers receiving other relevant information, for example, about sustainability or health benefits, or receiving no additional information at all.

3.2. Materials and Methods

Sample

The sample, consisting of Austrian citizens N = 295, is gender balanced (47/53% female/male). It mainly consists of young people, with a mean age of M = 21.39, SD = 4.18 years, age range 18 to 59 years. Many, but not all, of the participants are students, with 98.64% having a high school or university degree. Most participants indicate receiving an income in the range from 1000 € to 1500 € per month, which is relatively low compared to a population average of 1934 € per month.

Virtual supermarket

The computer-based virtual supermarket displayed six shelves containing different product groups (vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, dairy, bread). Each of the six main product groups had subcategories, including three or four conventional versus sustainable product pairs (see Appendix A III for a full list). Every single product was visually displayed with a photo and a short description. The sustainable options always had a label added to the description. This label was either the blue MSC logo (seafood) or the European green leaf (organic food). The picture and the description were identical for conventional and sustainable products with a price premium of 20–50% for sustainable products as this is assumed to correspond to the expected and accepted price premium for sustainable products [70].

Primes

Nine different primes were designed of which eight represent experimental conditions, divided into two main groups of four conditions, plus one control condition (a full list of primes can be obtained from the first author). We selected seafood and dairy as the target food groups to both secure comparability with and extend Study 1. The illustrations of seafood, dairy, and the control prime were kept as simple and iconic as possible to rule out the differences between the two food groups due to the illustrations. Three of the four seafood primes contained a textual message which was also purposely kept simple and short. The first message (referred to as the healthy condition) was “Refill your Omega-3 storage!” (translated from German by the first author, see Figure 4), the second prime (referred to as the unhealthy condition) was “Seafood contains pollutants!”, the third message (referred to as the sustainable condition, adding an MSC label to the picture) was “If you eat seafood, choose the MSC label!”, and the fourth prime did not entail any message (no text condition). The messages on the dairy were “Refill your calcium storage!” (healthy), “Dairy causes osteoporosis!” (unhealthy), “If you chose dairy, choose organic!” (sustainable, adding the European organic label to each item on the picture), and one no text condition. The control prime was an iconic palm tree combined with the message “Take holidays!”. The participants were exposed to the primes before starting the experiment. The primes were validated for recognisability on a group of 30 randomly selected university students at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology who had to name the food group on the signs.

Figure 4.

Illustration of Prime 1, the healthy condition in the seafood group.

Procedure

All of the participants were asked to complete the instruction document attached to blotting pads before starting the computer task in the lab. The primes were pinned onto the blotting pads, under the instruction sheets. The instruction document included information about the aim of the study (a cover story was used here, telling the participants that their online shopping behaviour was explored—the real purpose was revealed after the experiment), ethical consideration, and a request for consent. Information about the possibility to win the products selected in the online shop was included. After signing, the participants entered the online shop and could buy food items of their choice within a budget limit of 20 €. After selecting products, participants could “check out” and “pay”, moving to a final short questionnaire. Block 1 of the questionnaire contained general environmental attitude questions represented by items from the New Environmental Paradigm [71], criteria for choosing certain products (measured on a 7-point Likert scale), dietary restrictions, and demographics. Block 2 contained the manipulation check. The full questionnaire can be obtained from the first author.

3.3. Data Analysis

The dependent variable in this experiment was the number of products bought of a certain category, for example, the amount of seafood and dairy bought in total. Univariate analyses of variance were conducted with the different priming conditions as the grouping variable, and the amount of sustainable/nonsustainable seafood/dairy products bought as the dependent variable. Next, the interest in healthy or sustainable food types was included as covariates.

3.4. Results

The purchase of sustainable products was positively correlated with general pro-environmental attitudes (r = 0.26, p < 0.001) and with the importance of sustainability (r = 0.42, p < 0.001) and organic origin (r = 0.71, p < 0.001) as choice criteria, and negatively correlated with the importance of price (r = −0.36, p < 0.001) and caloric content (r = −15, p < 0.01) as choice criteria. The purchase of conventional products was positively correlated with the importance of price (r = 0.40, p < 0.001) and caloric content (r = 0.21, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with the importance of sustainability (r = −0.42, p < 0.001), organic origin (r = −0.72, p < 0.001), and taste (r = −0.16, p < 0.005).

A first analysis of variance was conducted aggregating all the four seafood prime conditions and all four dairy prime conditions while also comparing them to the control group. The dependent variable was total seafood sales. The omnibus test showed a significant F-value F(2,292) = 8.72, p < 0.001. Post hoc analysis showed significant differences between fish prime (M = 1.21, SD = 0.87) and milk prime (M = 0.87, SD = 0.86) conditions (p = 0.004) as well as between fish prime conditions and the control group (M = 0.63, SD = 0.98) p = 0.02. No significant difference in seafood sales was found between milk prime conditions and the control group.

A second analysis of variance separating between all the nine conditions revealed a significant difference in seafood purchase between the nine treatment categories (F(8,286) = 2.47, p = 0.01). However, Bonferroni post hoc tests showed that only one group difference was significant: the one between the no text seafood prime (M = 1.33, SD = 0.86) and the control condition (M = 0.63, SD = 0.98; p = 0.04). Although all seafood conditions led to a higher number of seafood items purchased than the dairy conditions (see Table 2), none of the differences between seafood and dairy conditions were significant when analysed at this disaggregated level.

Table 2.

Average number of items sold in the categories “seafood” and “dairy” in different conditions.

An identical analysis was conducted with dairy products as the dependent variable. When dairy and seafood prime conditions are aggregated to increase statistical power, the analysis revealed a significant difference in dairy purchased between seafood versus dairy versus control group (F(2,292) = 5.28, p < 0.006). The post hoc analysis revealed significant differences between the dairy prime group (M = 1.80, SD = 1.09) and the seafood prime group (M = 1.37, SD = 1.14; p = 0.006). The differences between the seafood prime group and the control group and between the dairy prime group and the control group were not significant.

At the disaggregated level, distinguishing between all nine conditions, the omnibus test did not show significant differences between groups (F(8,286) = 1.81, p = 0.08; values for the different conditions can be seen in Table 2). However, similar to the seafood consumption pattern, a tendency for higher dairy purchase manifests itself across dairy primes.

To test if sustainable purchase primes led to increased purchase of sustainable products in general or for the specific product category, three additional analyses of variance were conducted. When aggregating across sustainable prime conditions, no effect was found on the purchase of organic-labelled products across product categories. Also, no increase in sustainable seafood/dairy purchase was found as a consequence of being primed with sustainable seafood/dairy. Including product preferences for organic origin or sustainable produce as covariates also did not lead to the increase of sustainable purchase as a consequence of sustainable primes being significant.

To see if the purchase of any other product category was affected by the primes, the same analyses were run for all other product groups. No significant differences were found for the purchase of vegetables, fruit, meat, or bread across and between the nine treatment conditions. The manipulation check revealed that the majority of participants could not remember what was written on the sign, while in the open question most people indicated rough ideas of what the picture was (“something with fish” Participant 2, “A white fish on blue ground” Participant 13, “dairy products” Participant 62, translated by the first author from German).

3.5. Discussion

The study confirmed our hypothesis that a subtle product category prime, such as the one included in the signs employed in Study 1, can subsequently increase the purchase of this product category, independent of the attached message. For both product categories, seafood and milk, a general increase in the number of items bought resulted from having been exposed to primes displaying the respective product. However, the text in the prime did not lead to a significant change in buying patterns in the direction promoted by the text. This was despite the fact that the text was very short and precise and, therefore, presumably easy to process.

All of the health, health risk, sustainable, and no text conditions led to a similar increase in purchases within the primed category. If participants had processed the text, one would expect that, for example, the sustainability message would lead to a higher increase in the sale of sustainable than of other products within the product category, but it did not. Therefore, the only information sticking in participants’ minds is the general food category (e.g., seafood), whose likelihood of being chosen is then elevated. Presumably, the simple picture on the sign primed this particular product category and made it more accessible in the minds of the participants, which subsequently increased the likelihood of purchases within that product category. Hence, consumers’ disinclination to process textual information in the buying situation needs to be taken into account when promoting, for example, more sustainable diets.

3.6. Limitations

Some limitations need to be considered when interpreting these results. Participants were asked to make choices within a budget of 20 €, which might have resulted in slightly different choices than without or with randomly assigned budgetary constraints. All of the participants spent between 19.00 € and 20.00 € at the end, which confirms that they might have tried to maximise their output by smart product combinations.

Since this study was conducted in a laboratory setting and with a stated budget constraint, it is not a perfect replication of real-world buying situations where additional factors impact the purchase decision, like overall budget constraints, the behaviour of fellow customers, product placement, or smells. It is therefore recommended that the results are validated in a real-world setting.

4. General Discussion

The results of this research suggest that popular social norms advertisement, like, “More than 75% of the seafood customers in this store bought MSC-labelled seafood”, might not influence supermarket shoppers’ purchasing patterns in the intended way. In fact, rather than promoting a more sustainable diet, they might do the opposite while at the same time leading to increased consumption of seafood (in this case) in general. Messages, including the social norms ones promoting seafood from sustainable origin, seems to be processed in a very shallow way in the busy and message-over-crowded supermarket setting. Shoppers primarily seem to comprehend the overall theme seafood—a product category which then indeed gets primed, increasing the likelihood that they will indeed buy some. At least in the present studies, texts and labels promoting sustainability were apparently not processed sufficiently to produce the intended effect, and instead, consumers relied on their usual choice heuristics for this product group [55].

However, substantial differences were identified between the Norwegian and the German supermarkets. In the former, but not in the latter, an information prompt about the sustainability label alone led to a significant increase in the sustainability labelled share of seafood sales. This may be due to a mixture of factors. First, this is the experimental condition where least text was added, and the text was even simpler and shorter in the Norwegian case, where there was only one label on the sign, while there were two in the German case. The text being simpler may have made it easier to grasp its meaning (i.e., “less is more”). Second, there were on average twice as many sustainability-labelled seafood products in the Norwegian than in the German supermarkets, making sustainability labels more salient in the shopping context in Norway than in Germany. This may have meant that the Norwegian shoppers may have been relatively more exposed to and therefore more familiar with the sustainability label than the German shoppers. Third, the share of sustainability-labelled seafood products sold was also twice as high at baseline in the Norwegian than in the German supermarkets, which may mean that the Norwegian shoppers had more experience with sustainability-labelled seafood and therefore could also process this information on the sign with less effort.

In the Norwegian case, adding social norms information to the sign neutralized the positive effect of labelling information on sales, leading to a significant drop in sales compared with labelling only. In the German case, adding social norms information also led to a significant drop in sales, both compared with the prompt-only condition and compared with baseline. The negative effect in Norway could be due to the increased amount of information confusing shoppers and dragging attention away from the labelling information. However, this cannot explain the findings in the German case. The significant drop in the sustainability share compared with baseline in the German supermarkets suggests that the social norms messages were demotivating shoppers and perceived as something negative about buying sustainability-labelled products. A possible reason is that German shoppers found the social norm messages pressing or manipulating, which led to psychological reactance. These findings are in line with previous research revealing trait reactance and the importance of autonomous buying behaviour as significant predictors of situational reactance on a sample of German consumers [72]. Psychological reactance is also a possible explanation for the drop in the share of sustainability-labelled seafood when adding social norm messages to the prompt only in Norway.

Hence, it can be concluded that the main effect of messages in the supermarket context aiming to make individuals consume products with specific (sustainability) characteristics within a product category is to promote the consumption of this product category in general, without increasing the share of sustainable produce. This is similar to the finding that telling people not to eat a particular product can have the opposite of the intended effect, due to the message priming the product, as it was found in Study 2.

An important implication for the promotion of sustainable consumption options is to focus on simple messages, avoiding long, fuzzy, and complex messages [73]. For example, instead of promoting “eating less meat”, promoting “plant-based alternatives” would be more effective. Indeed, campaigns promoting the consumption of more fruit and vegetables [35,74] are probably the main reason why meat consumption has decreased in Europe in the most recent decades. However, it also shows that promoting sustainably produced products within categories that are unsustainable can be complicated. The use of labels and symbols to identify sustainable products has shown good results in the past [1]. However, the design and placement of labels and symbols need to be based on a thorough understanding of how consumers make choices in the product category [26,75]. Also, such a label or symbol needs to be promoted in a way that makes the actual logo and its core meaning easily accessible in the consumers’ minds in the moment of decision, preferably more accessible than other product characteristics. Potentially, a general “green” logo on all products following sustainable certification guidelines would be an option. If one logo standing for sustainability could be applied to all product groups, the meaning of this logo will be easy to process and its priming is likely to be effective. In this way, consumers following sustainability goals would more easily identify their preferred products with a symbol standing for sustainability being salient in their minds. The results of these two studies suggest that the display of pictures or icons is more efficient than the display of text, especially in real-life purchase situations where written information is hardly read or processed carefully. More research is needed on how to make the sustainable logo and its core meaning more salient in consumers’ minds at the moment of decision. From this research, it is concluded that just adding text with label information and social norms messages is not the way to go to increase the share of sustainable product alternatives. Additional text will often not be processed in the purchase decision situation or the message will be forgotten as soon as other product characteristics come into play. This also illustrates that to reach the desired effects and minimize the risk of side effects, careful evaluation is necessary before communication strategies are implemented.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R. and C.A.K.; Methodology, I.R., J.T. and C.A.K.; Validation: I.R., J.T. and C.A.K.; Formal Analysis, I.R.; Investigation, I.R.; Resources, I.R., C.A.K. and J.T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, I.R.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.T.; Visualization, I.R. and C.A.K.; Supervision, C.A.K. and J.T.; Project Administration, I.R.; Funding Acquisition, C.A.K.

Funding

This research was funded by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway as part of a stipend granted to the first author.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a stipend granted to the first author by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, in Trondheim, Norway. Our special thank you goes to all the store managers who were willing to collaborate with us on this study. In Norway, this includes managers and employees in Bunnpris Elgsetergate Trondheim, Coop Valentinlyst Trondheim, Coop Moholt Trondheim, Coop Jakobsli Trondheim, and Coop Nardo Trondheim. In Germany, we want to thank managers and employees of Real Nürnbergerstrasse Würzburg, Aldi Gerbrunn, Aldi Frankfurterstrasse Würzburg, and Aldi Mainaustrasse Würzburg for their support. Another special thank you goes to Réka Szendrö, Eryk Krysowski, and all lab assistants from the VCEE Vienna Choice Laboratory who supported our project immensely regarding programming, administration, and data collection. Furthermore, we thank Christian Schuster from Christian Schuster Illustrations for designing the primes for Study 2 and Vivian Thonstad Moe from NTNU Grafisk Senter who supported the production of primes in Study 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Product overview for products included in Study 1.

Table A1.

Product overview for products included in Study 1.

| Product | Price Per 100 g | Label | Weight | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish Sticks Xtra | 1.52 Nok | MSC | 900 g | Norway |

| Fish sticks Sprø | 2.47 Nok | - | 900 g | Norway |

| Fish sticks Findus | 13.11 Nok | MSC | 360 g | Norway |

| Fish sticks Lerøy | 9.00 Nok | - | 450 g | Norway |

| Fish Gratin Fransk | 15.67 Nok | MSC | 400 g | Norway |

| Fish Gratin Frionor | 18.76 Nok | - | 300 g | Norway |

| Fish Gratin Xtra | 7.20 Nok | MSC | 450 g | Norway |

| Fish Gratin Lofoten | 9.93 Nok | - | 450 g | Norway |

| Crispy Cod Findus | 9.64 Nok | MSC | 500 g | Norway |

| Crispy Cod Xtra | 7.72 Nok | - | 600 g | Norway |

| Crispy Cod Findus | 28.41 Nok | MSC | 240 g | Norway |

| Crispy Cod Lofoten | 24.46 Nok | - | 320 g | Norway |

| Cod Xtra | 9.05 Nok | MSC | 400 g | Norway |

| Cod Lerøy | 11.55 Nok | - | 400 g | Norway |

| Pollack Xtra | 8.15 Nok | MSC | 400 g | Norway |

| Pollack Lerøy | 11.33 Nok | - | 400 g | Norway |

| Fish Soup Findus | 9.16 Nok | MSC | 500 g | Norway |

| Fish Soup Stabburet | 4.65 Nok | - | 800 g | Norway |

| Shrimps Grønland | 9.27 Nok | MSC | 1000 g | Norway |

| Shrimps | 11.75 Nok | - | 760 g | Norway |

| Salmon Wild Almare | 1.72 € | MSC | 250 g | Germany |

| Salmon Premium Almare | 1.60 € | - | 250 g | Germany |

| Salmon TIP | 1.99 € | ASC | 250 g | Germany |

| Salmon Berida | 1.84 € | - | 250 g | Germany |

| Shrimps Femeg | 2.22 € | MSC | 225 g | Germany |

| Shrimps Real | 1.77 € | - | 225 g | Germany |

| Shrimps Herbs Femeg | 2.22 € | MSC | 225 g | Germany |

| Shrimps Herbs Real | 1.77 € | - | 225 g | Germany |

| Tuna Filet Real | 1.95 € | MSC | 400 g | Germany |

| Tuna Steak Real | 3.12 € | - | 320 g | Germany |

References

- Hertwich, E.G.; Peters, G.P. Carbon footprint of nations: A global, trade-linked analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6414–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukker, A.; Jansen, B. Environmental impacts of products: A detailed review of studies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1579SDGs%20Proposal.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Belz, F.-M. Nachhaltigkeits-Marketing: Konzeptionelle Grundlagen und empirische Ergebnisse. In Nachhaltigkeits-Marketing in Theorie und Praxis; Deutscher Universitätsverlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Rowe, I.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. The role of consumer purchase and post-purchase decision-making in sustainable seafood consumption. A Spanish case study using carbon footprinting. Food Policy 2013, 41, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E. An enduring concern. Public Perspect. 2002, 13, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude-behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Foster, C. Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour—Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. Hum. Policy Dimens. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D. Fostering Sustainable Behavior: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W. Strategies for Promoting Proenvironmental Behavior Lots of Tools but Few Instructions. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1956, 70, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct—A Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human-Behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Demaine, L.J.; Sagarin, B.J.; Barrett, D.W.; Rhoads, K.; Winter, P.L. Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Soc. Influence 2006, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Social norms and cooperation in real-life social dilemmas. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, K.; Rettie, R.; Patel, K. Marketing social norms: Social marketing and the ‘social norm approach’. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, R.; Burchell, K.; Riley, D. Normalising green behaviours: A new approach to sustainability marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, R.; Barnham, C.; Burchell, K. Social Normalisation and Consumer Behaviour: Using Marketing to Make Green Normal; Kingston University: Kingston, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.A.; Neighbors, C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. J. Am. Coll. Health 2006, 54, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, H.W.; Craig, D.W. A successful social norms campaign to reduce alcohol misuse among college student-athletes. J. Stud. Alcohol 2006, 67, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, J.M.; Perkins, H.W.; Craig, D.W. Misperceptions of peer norms as a risk factor for sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among secondary school students. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1916–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsari, B.; Carey, K.B. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. J. Stud. Alcohol 2003, 64, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, D.A.; Miller, D.T. Pluralistic Ignorance and Alcohol-Use on Campus—Some Consequences of Misperceiving the Social Norm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie-Mohr, D.; Smith, W. Fostering Sustainable Development. An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ölander, F.; Thøgersen, J. Informing Versus Nudging in Environmental Policy. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 37, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; HeinOnline: Chacago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. Subjektive Barrierer Som Forhindre at Nordmenn Handler Økologisk Mat; NTNU: Trondheim, Norway, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J. Psychological determinants of paying attention to eco-labels in purchase decisions: Model development and multinational validation. J. Consum. Policy 2000, 23, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; de Vet, E.; de Ridder, D.T.; de Wit, J.B. The potential of peer social norms to shape food intake in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of effects and moderators. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Fleming, A.; Higgs, S. Prompting Healthier Eating: Testing the Use of Health and Social Norm Based Messages. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, C.R.; Niculescu, M.; Just, D.R.; Kelly, M.P. Shopper marketing nutrition interventions: Social norms on grocery carts increase produce spending without increasing shopper budgets. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, M.; Nilsson, A. I saw the sign: Promoting energy conservation via normative prompts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.M.; Liu, J.; Robinson, E.L.; Aveyard, P.; Herman, C.P.; Higgs, S. The Effects of Liking Norms and Descriptive Norms on Vegetable Consumption: A Randomized Experiment. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P.W. Changing behavior with normative feedback interventions: A field experiment on curbside recycling. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.L.; Pierce, M.; Bargh, J.A. Priming effect of antismoking PSAs on smoking behaviour: A pilot study. Tob. Control 2014, 23, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.N.; Killen, J.D. Do cigarette warning labels reduce smoking? Paradoxical effects among adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1997, 151, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earp, B.D.; Dill, B.; Harris, J.L.; Ackerman, J.M.; Bargh, J.A. No sign of quitting: Incidental exposure to “no smoking” signs ironically boosts cigarette-approach tendencies in smokers. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 2158–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; Bartle, N.; Wardle, J. Social norms and diet in adolescents. Appetite 2011, 57, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollen, S.; Rimal, R.N.; Ruiter, R.A.; Kok, G. Healthy and unhealthy social norms and food selection. Findings from a field-experiment. Appetite 2013, 65, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stok, F.M.; de Ridder, D.T.; de Vet, E.; de Wit, J.B. Minority talks: The influence of descriptive social norms on fruit intake. Psychol. Health 2012, 27, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, E.; Oleary, M. The Relative Effectiveness of Models and Prompts on Energy-Conservation—A Field Experiment in a Shower Room. J. Environ. Syst. 1982, 12, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social Influence; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.S.; Meier, S. Social comparisons and pro-social behavior: Testing “conditional cooperation” in a field experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 1717–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P.; Hackett, R.; Kuleshnyk, I. The effects of self-attention and public attention on eating in restrained and unrestrained subjects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, D.A.; Herman, C.P.; Polivy, J.; Pliner, P. Self-presentational conflict in social eating situations: A normative perspective. Appetite 2001, 36, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Wong, N.; Abe, S.; Bergami, M. Cultural and situational contingencies and the theory of reasoned action: Application to fast food restaurant consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2000, 9, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, M.M.; Koch, C.; Rangel, A. Consumers can make decisions in as little as a third of a second. Judgement Decis. Mak. 2011, 6, 520–530. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J.; Jørgensen, A.K.; Sandager, S. Consumer decision making regarding a “green” everyday product. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Seiter, J.S., Gass, R.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Behavioural Insights Team. Applying Behavioural Insight to Health; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, I.G.M.; Klockner, C.A. The Psychology of Sustainable Seafood Consumption: A Comprehensive Approach. Foods 2017, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thøgersen, J. Promoting “green” consumer behavior with eco-labels. In New Tools for Environemntal Protection: Education, Information, and Voluntary Measures; Dietz, T., Stern, P., Eds.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrøm, M. Seafood Labelling in Norway; Richter, I., Ed.; Marine Stewardship Council: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, I.; Thogersen, J.; Klockner, C.A. Sustainable Seafood Consumption in Action: Relevant Behaviors and their Predictors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine Stewardship Council. Seafood Consumers Put Sustainability before Price and Brand; MSC: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Fish and fishery products—World apparent consumption statistics based on food balance sheets. In FAO Yearbook—Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics; FIGIS: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.S.; Nisbet, E.C. Boomerang Effects in Science Communication. Commun. Res. 2011, 39, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.; Ralston, R.; Bigsby, E. Teens’ Reactance to Anti-Smoking Public Service Announcements: How Norms Set the Stage. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, R.; Gawronski, B.; Strack, F. At the boundaries of automaticity: Negation as reflective operation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. External validity of “trivial” experiments: The case of laboratory aggression. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, E.; Chen, Q.; McAdams, M.; Yi, J.; Hepler, J.; Albarracin, D. From primed concepts to action: A meta-analysis of the behavioral effects of incidentally presented words. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 472–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargh, J.A.; Chartrand, T.L. The mind in the middle. In Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 253–285. [Google Scholar]

- Krystallis, A.; Chryssohoidis, G. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food—Factors that affect it and variation per organic product type. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt, M.; Schrader, U. Consumer reactance against loyalty programs. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R. Nudges that fail. In Behavioural Public Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 4–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rekhy, R.; McConchie, R. Promoting consumption of fruit and vegetables for better health. Have campaigns delivered on the goals? Appetite 2014, 79, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thøgersen, J.; Nielsen, K.S. A better carbon footprint label. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 125, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).