Startups’ Roads to Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- focusing on the SHELL categories, which are the typical failure patterns?

- do causes for failure change over the lifecycle of startups?

- are there clear relationships between startups failures cause and the industry in which they operate?

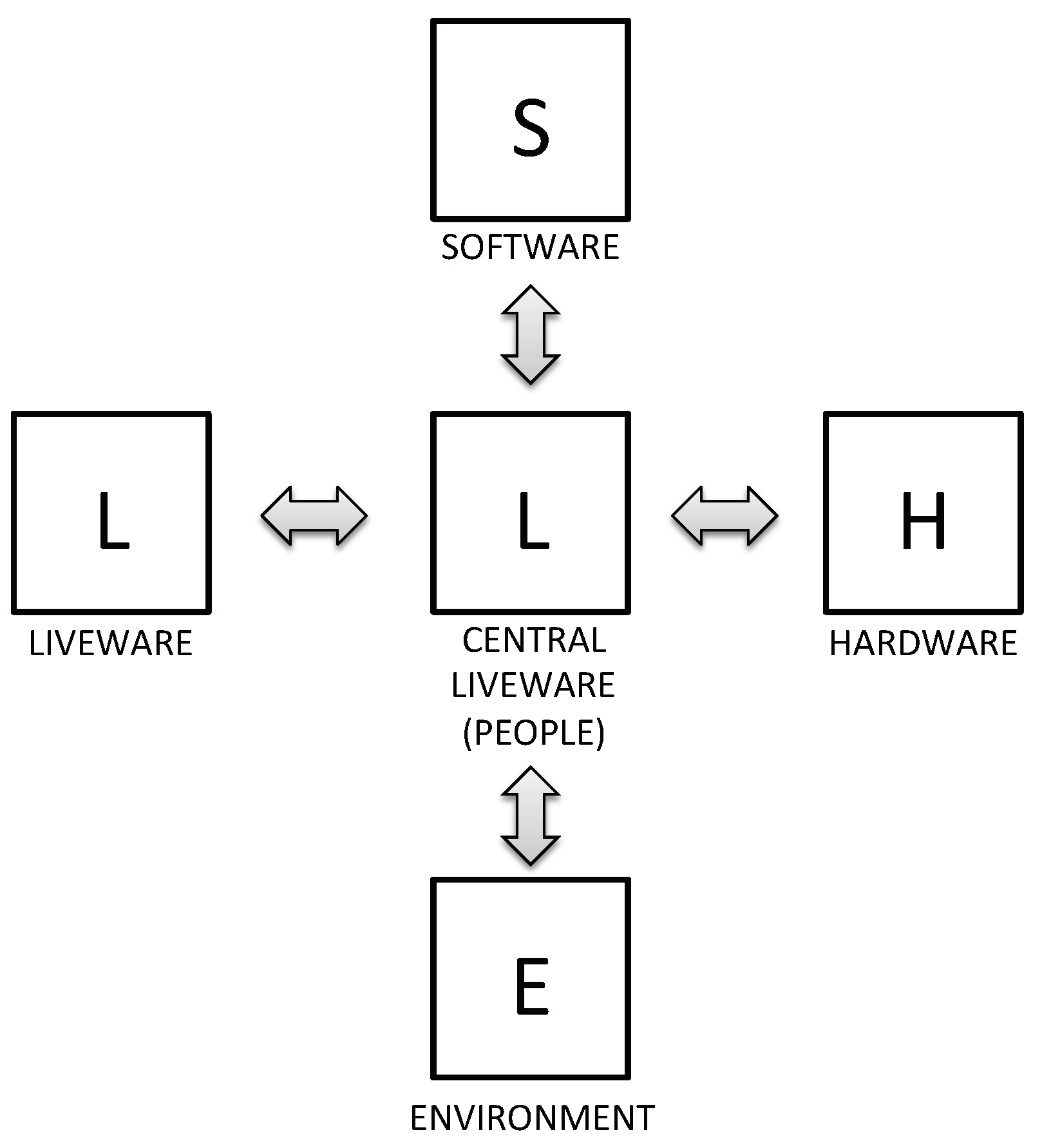

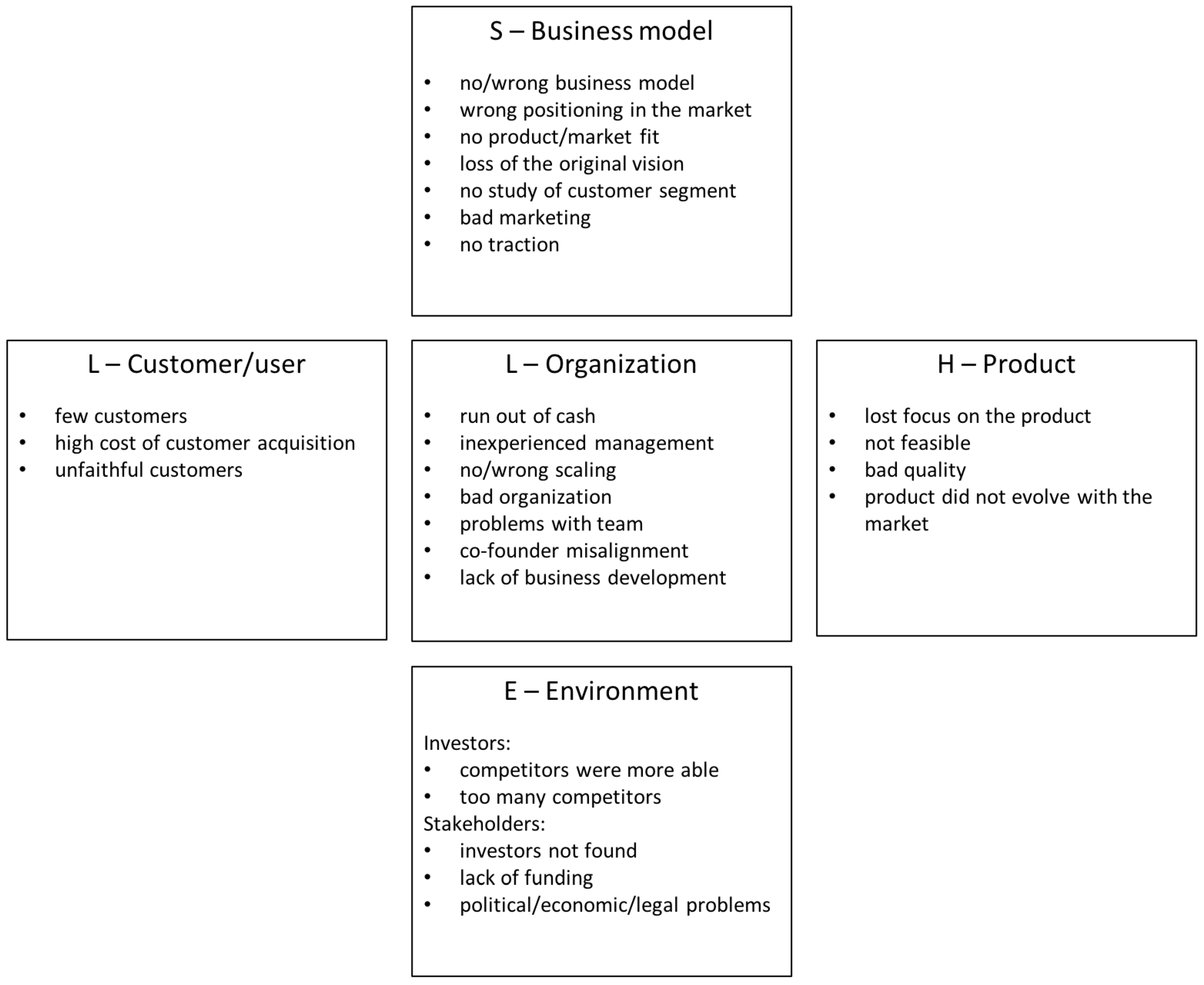

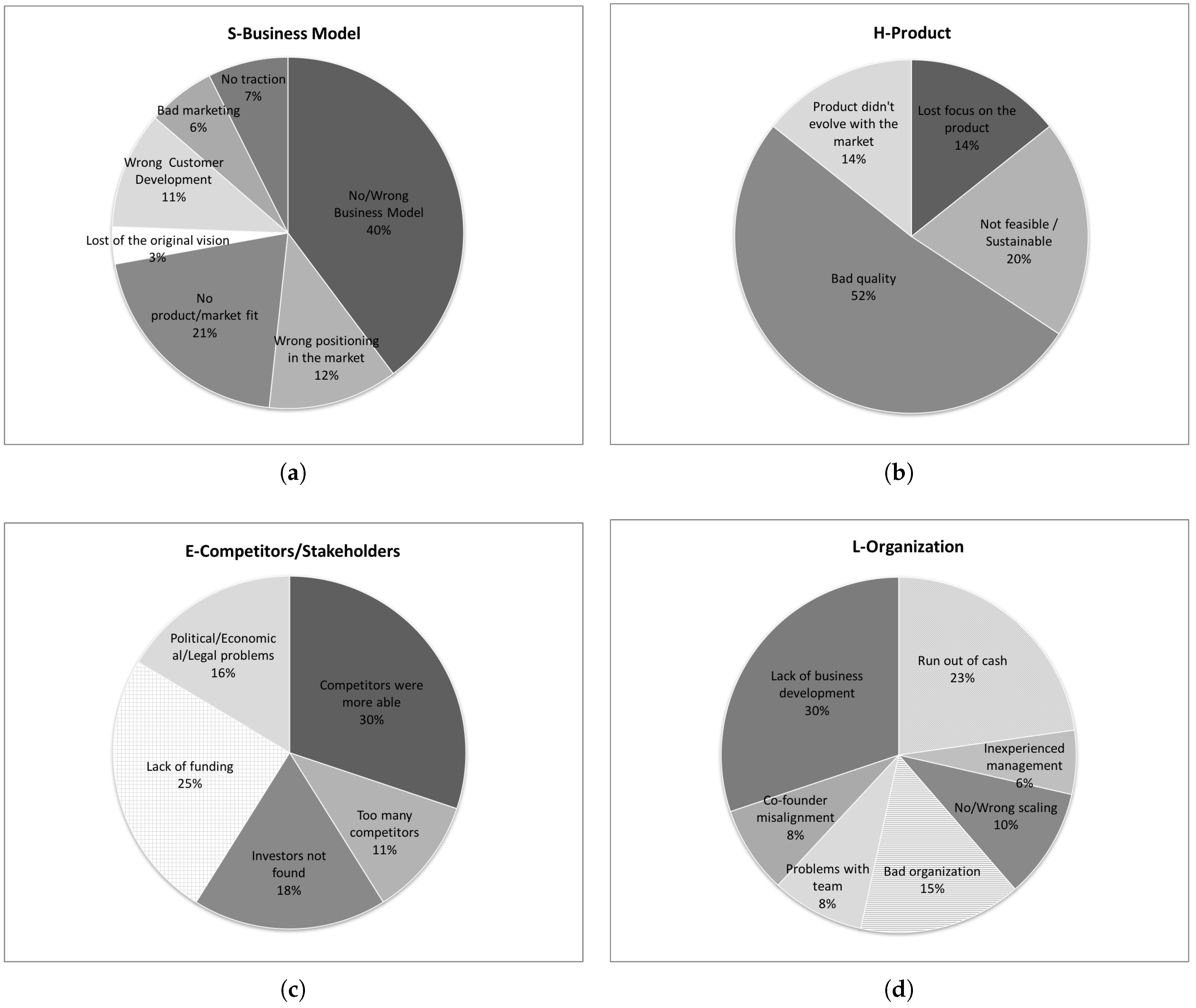

- Software. It is the non-physical and intangible part of the startup and principally consists of the business model that, according to the definition proposed by [52], describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. Thus, in this context, the term software does not refer to Information Technology but is composed by all the aspects that are thought to ensure the success of the product or service offered by the startup in the market, in a more commercial perspective. In particular, this building block includes the following subcategories:

- -

- No/Wrong Business Model. As mentioned earlier, the business model is a representation of the way in which the firm creates value for its customers and captures part of it to generate profits. According to [53], business models are a defining feature of any firm, but the clarity of the business model is particularly true when dealing with technological innovations. The business model should not be considered as a definitive and static representation of the startup. A business model is provisional, in the sense that it must be continuously evaluated and improved, based on feedback from the market and from the broader ecosystem where the startup operates [54]. Thus, the right business model is rarely clear early on in emerging industries: entrepreneurs who have a good—albeit imperfect business model—but are able to learn and make it evolve, are those more likely to succeed [53,54].

- -

- Wrong positioning in the market. The absence of a product/market fit is damaging the product/service itself and the success of the business model. In fact, the product/market fit means being in the right market with the right product or service capable to satisfy it. On the contrary, the wrong positioning implies the wrong knowledge of the product/service with consequent bad performance or the risk to begin in the “stuck in the middle” position identified by [55].

- -

- No product/market fit. A more severe case of wrong product/market fit occurs when the product or service can potentially satisfy needs or solve problems, but these are actually not perceived by the customers.

- -

- Loss of the original vision. This case occurs when the founders of a startup are too focused on the product, and its technical development and improvement, and end up losing their initial vision and customer orientation. Unfortunately, they realize the deviation from the original vision only when too close to failure.

- -

- Wrong customer development. According to [52], customers comprise the heart of any business model. Each segment of customers is characterized by specific needs, behavior, and willingness to pay for the product or service offered. Thus, it is important to identify the different segments carefully and to take a conscious decision about the ones to serve, to focus the marketing campaign for the right customers. In fact, a good product or service sold to the wrong segment would not lead to the success.

- -

- Bad marketing. This case refers to marketing campaigns that are not correctly conceived or executed.

- -

- No traction. The term business traction refers to the progress of a startup and the motion it gains as the business grows. Not having enough traction implies the startup is unable to grow at sufficient speed, therefore losing competitive advantage and/or interest by investors and other stakeholders.

- Hardware. It is the physical element of the startup and it is mainly represented by the product or service offered to the customer segments (i.e., materials, devices, platforms, websites, etc.). It includes the following subcategories:

- -

- Lost focus on the product. This is related to the insufficient attention paid to product development. In fact, according to [56], a startup fails when it ignores a user’s wants and needs, whether consciously or accidentally, and offers a user-unfriendly product.

- -

- Not feasible/sustainable. This subcategory includes issues related to the technical feasibility ignored by the startup or emerged later, making impossible the design and the development of the product.

- -

- Bad quality. It refers to more general problems related to the product and its quality. For example, this issues affect services or mobile applications (e.g., the product does not work well, there are bugs in the code, the mobile app is not responding as it should do, there are problems in the operations, etc.).

- -

- Product did not evolve with the market. The product or service continues to fulfill the original need for which they were thought, but the current market is changed. Thus, the functionality it is not fitting with the current customers’ needs.

- Environment. This building block illustrates the physical context in which the startup operates. It involves the internal environment, which includes the impact that the competitors have on the startup and the external one that considers the effect of the stakeholders’ operations, also considering the economic and political situation around the startup. From the competitors’ point of view, the environment is composed of two subcategories:

- -

- Competitors were more able. Often, a startup deals with too strong competitors, which have a consolidated positioning with a relevant market share and the access to the distribution channels or to technologies, resources, and complementary assets. Thus, although the startup offers a good product, these conditions make difficult to gain a good portion of the customer segment.

- -

- Too many competitors. The more fragmented market, characterized by a high number of competitors with small share does not allow new incomers to gain a relevant position.

While, from the stakeholders’ point of view, the environment includes:- -

- Investors not found. One of the main common reason for running out of cash is related to a lack of investors’ interest either at the seed follow-on stage or at all. This could be caused by a bad presentation of the product or service offered or connected to one of the previous categories [56].

- -

- Lack of funding. The absence of investors is not the only reason for the startup’s failure. In fact, many startups deal with the problem of raising small amounts of investments, which are not enough for the development of the business, combined with a bad organization of these resources.

- -

- Political/Economic/Legal problems. The political and economic situations of the environment where the startup operates could affect its success, due to regulations or economic conditions, influencing the willingness-to-pay of the potential customer segments. Moreover, in specific fields like the music industry or those where the copyright is highly critical, the legal challenges represent a reason for the startup failure, due to the consequent expenditures on lawyers and royalties [56].

- Liveware It means the human side of the startup system (founders, management, and workers). This component considers human performance, organization, capabilities, and limitations. It is divided into two parts: one referred to the external environment, which considers the customer/user side and the second one related to the internal part, composed by the people and the organization within the startup.

- L-Customer/user

- -

- Few Customers. This factor of startup failure is related to the previous reasons, especially to the wrong positioning, the maturity of the market and the competition effects or the positioning in a niche market, etc. All these reasons could determinate the reach of only a small part of customers, which is not enough for the sustainability of the business.

- -

- Problems in customer acquisition. Wrong marketing efforts could generate a high cost to acquire customers, not balanced by the number of customers really acquired.

- -

- Unfaithful customers. In the recent years, the customers became more conscious and attracted from the different promotions offered by the competitors, increasing the level of competition and the risk of a continuous war of prices that make customers’ loyalty fragile.

- L-Organization

- -

- Run out of cash. This reason is normally correlated to one or more of the previous categories, as consequence of a bad management of the resources and the investments, or bad business development, wrong customer, market study, etc.

- -

- Inexperienced management. Frequently, the startup founders have hard skills and very technical backgrounds with a lack of cross-domain and commercial knowledge. This brings to a well- developed product/service but the absence of business model and business development.

- -

- No/Wrong scaling. The decision of a startup to undertake a systematic growth could reveal the threat of a failure, due to a difficult pivot or a premature scaling compared to the market situation, or to a higher working capital requirement than the scaling operation might need. Thus, the decision to scale should be taken after a deep study of the startup position and situation to understand if the startup is ready to manage higher volumes, how big the growth can be and if increasing volumes will also increase the profit.

- -

- Bad organization. A startup is usually a chaotic environment. Thus, rules, roles, and tasks have to be well organized and assigned to each member of the team for efficiently managing all the activities. Moreover, one of the aspects related to the organization issue is the location of the team.

- -

- Problems with team. Disharmony on the team is one of the critical factor to the success of a startup, combined with a poor communication between the co-founders and the team, or within the components of the team itself [56].

- -

- Co-founder misalignment. Different backgrounds, qualifications, and specializations can create disagreements between co-founders and thus, cause bad decisions and bad management. These problems, if not solved, can lead a co-founder to leave or startup to fail, in the long run.

- -

- Lack of business development. As above mentioned, the highly technical team risks to have a lack of business development and thus, the absence of a commercial perspective, which includes the study of how to increase customers, sales and profits, and make the business more profitable and self-perpetuating.

3. Detailed Analysis

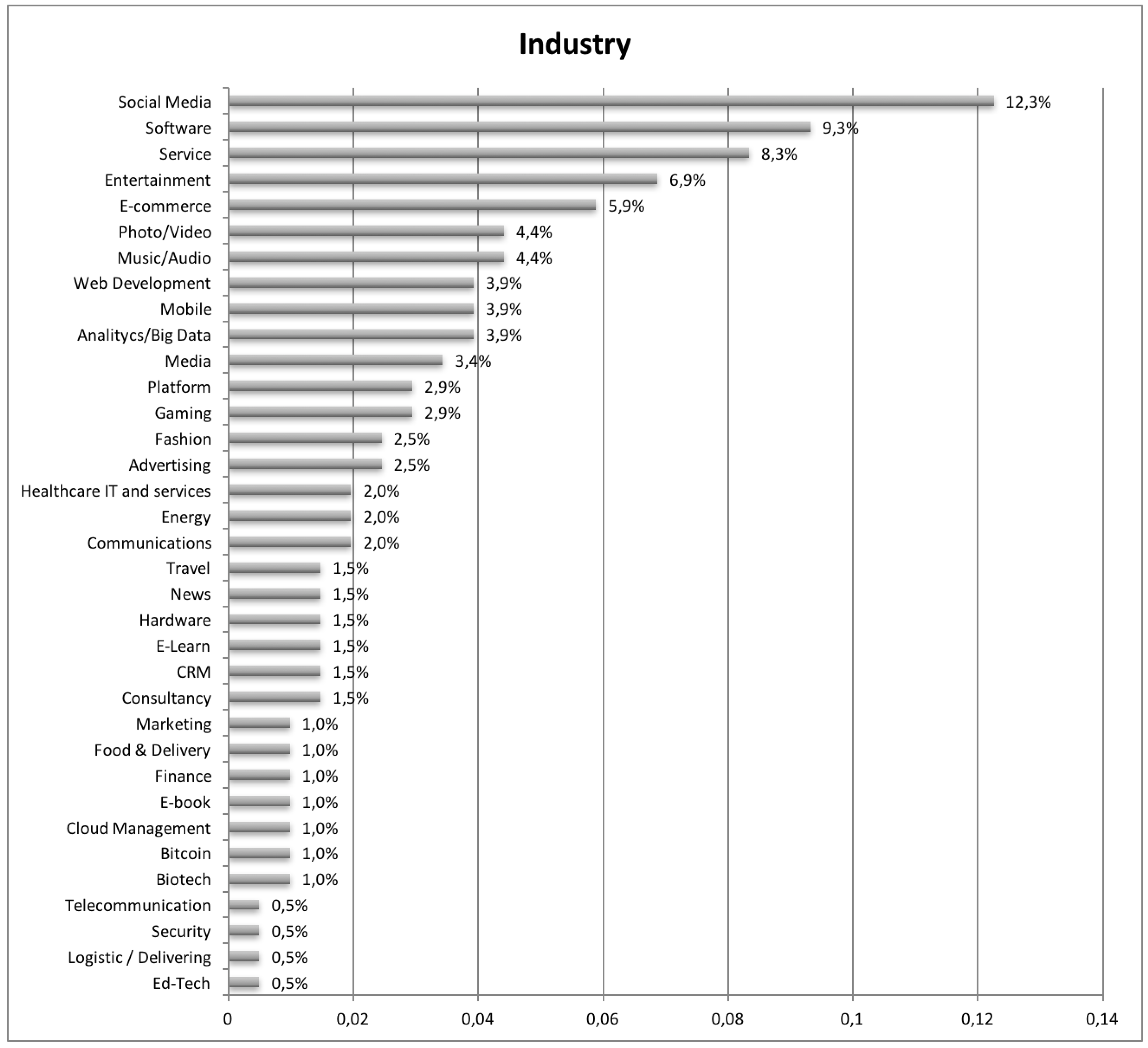

3.1. Data Settings

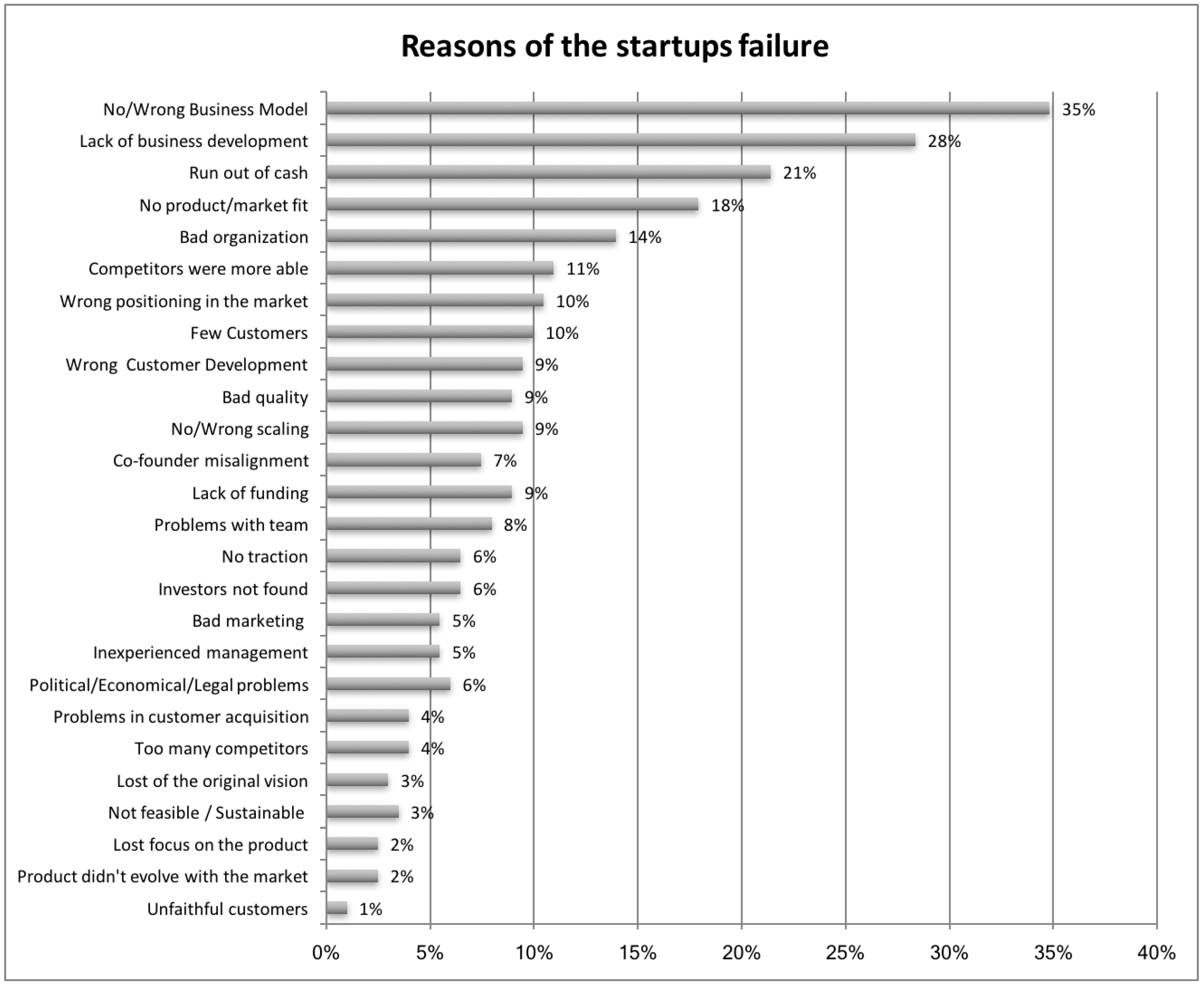

3.2. Results

- the SHELL categories;

- the duration of the startup.

3.2.1. SHELL Classification

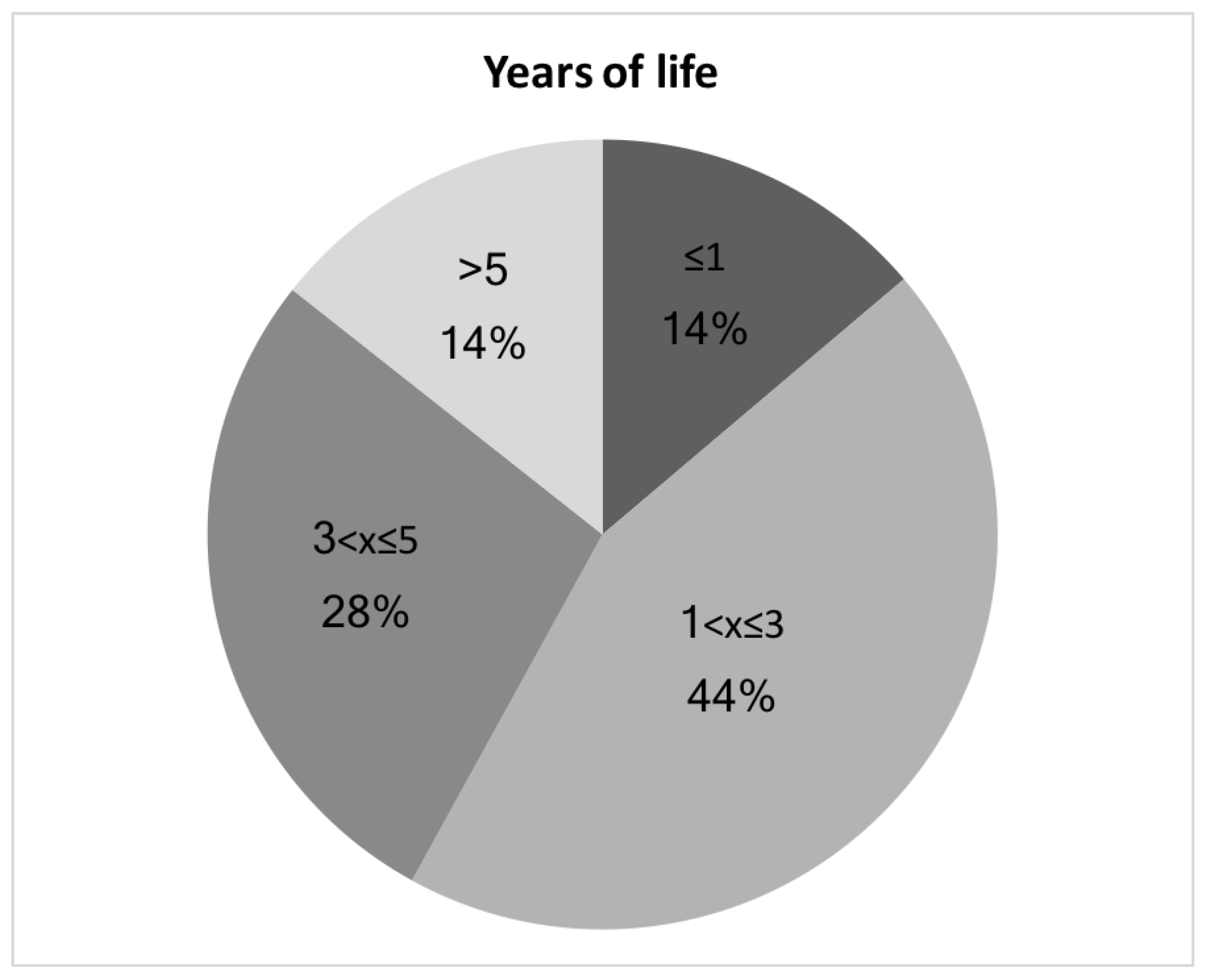

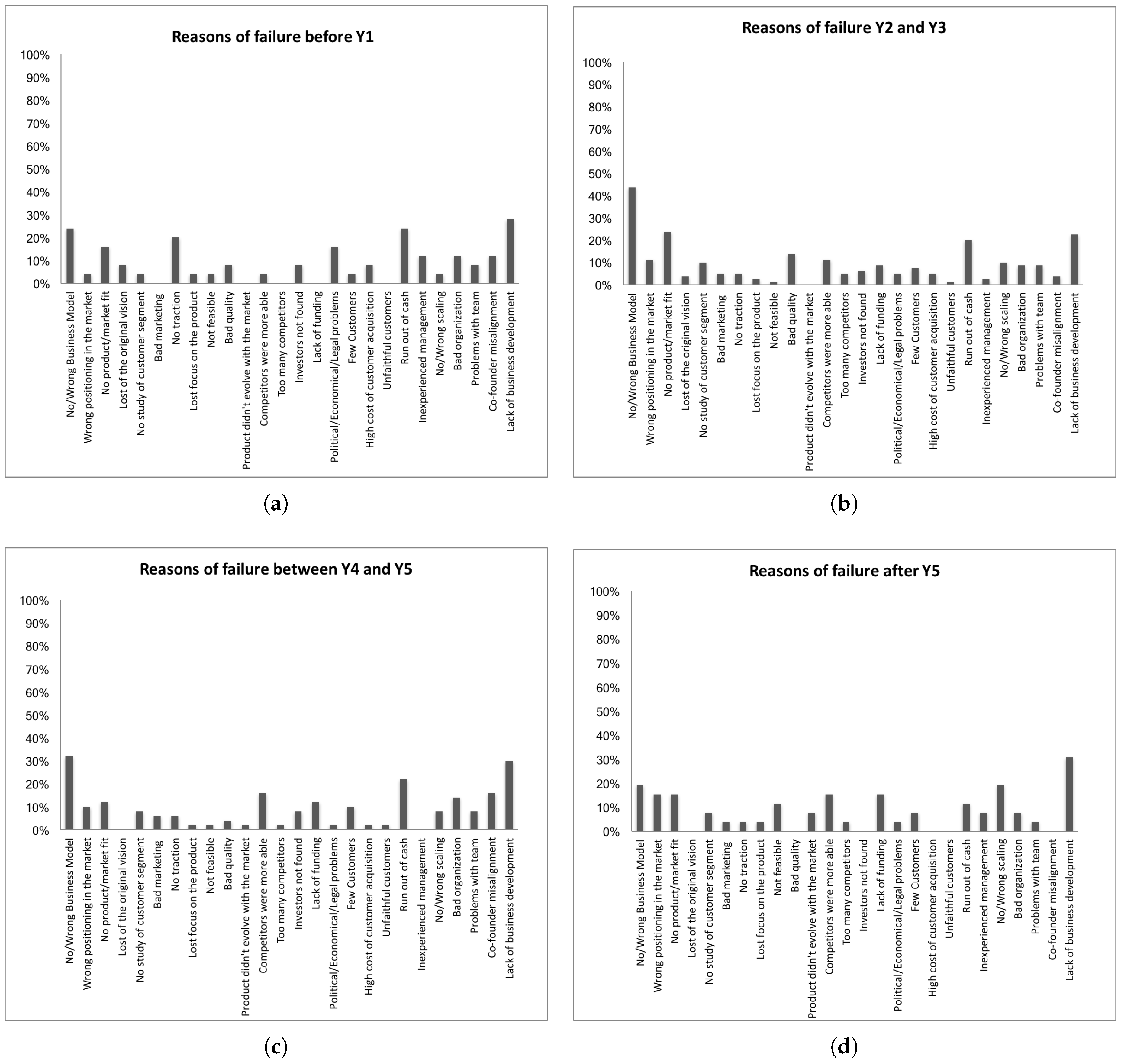

3.2.2. Years of Life

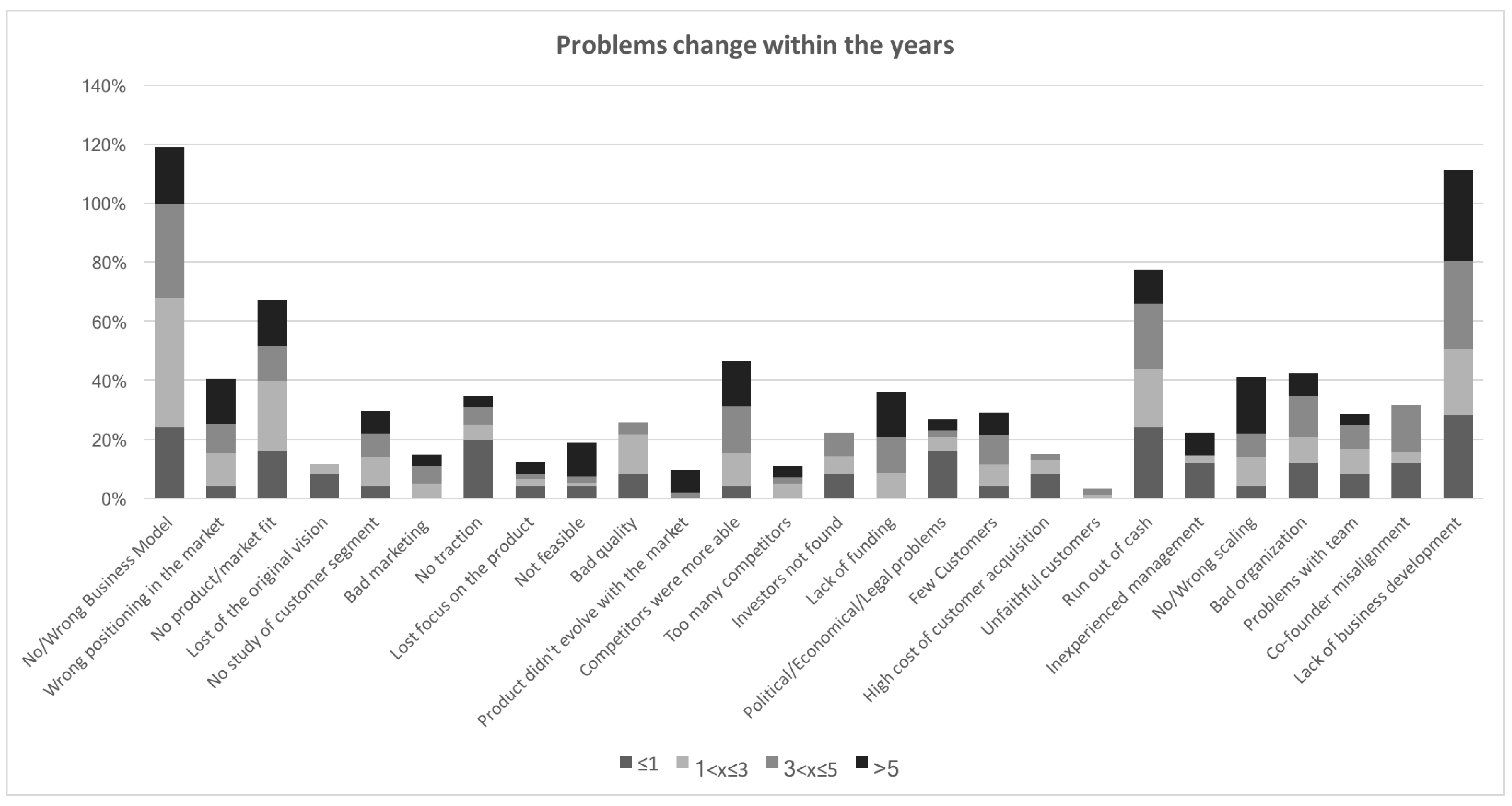

3.2.3. Mutual Contribution of Failure Causes

- We first make a broad clustering analysis on the startups using, as variables, all the startup failure reasons. More in depth, we considered, as clustering methods, k-means, Kohonem network and two-step cluster analysis [59]. When needed, the number of the cluster was fixed to 3, 4 and 5. Given all the combinations of clustering method and number of clusters, the combination with the best silhouette coefficient computed as , where denotes cluster labels which do not include case i as a member, while is the cluster label which includes case i. If , the Silhouette of case i is not used in the average operations.

- Given the best combination of method and parameters, for each cluster we analyzed the importance of the startup failures as predictors by computing importance of the predictor i as , where is the set of predictor fields and is the significance of predictor i defined as its .

4. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nightingale, P.; Coad, A. Muppets and gazelles: Political and methodological biases in entrepreneurship research. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2014, 23, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landström, G.; Harirchi, H.; Åström, F. Entrepreneurship: Exploring the knowledge base. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1154–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, D.; Brem, A. How do entrepreneurs think they create value? A scientific reflection of eric ries’ lean startup approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, W.H. Financial ratios as predictors of failure. J. Account. Res. 1966, 4, 71–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolari, J.; Glennon, D.; Shin, H.; Caputo, M. Predicting large us commercial bank failures. J. Econ. Bus. 2002, 54, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Early warning of bank failure. J. Bank. Financ. 1977, 1, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmijewski, M.E. Methodological issues related to the estimation of financial distress prediction models. J. Account. Res. 1984, 22, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydman, H.; Altman, E.I.; Kao, D.-L. Introducing recursive partitioning for financial classification: The case of financial distress. J. Financ. 1985, 40, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.Y. Neural network models and the prediction of bank bankruptcy. Omega 1991, 19, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, I.; Türkşen, I.; Canpolat, N. A currency crisis and its perception with fuzzy c-means. Inf. Sci. 2008, 178, 1923–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiam, S.C.; Tan, K.C.; Mamun, A.A. A memetic model of evolutionary pso for computational finance applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 3695–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arne, L.; Kalleberg, K.T.L. Gender and Organizational Performance: Determinants of Small Business Survival and Success. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 136–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, E.A.; Robinson, P.B. The Economic and Demographic Determinants of Self-Employment; Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College: Babson Park, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Marom, S.; Lussier, R.N. A business success versus failure prediction model for small businesses in Israel. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 4, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.; Watson, J. Small business failure and external risk factors. Small Bus. Econ. 1998, 11, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, D. Understanding new venture failure due to entrepreneur-organization goal dissonance. Vikalpa 2007, 32, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, M.L.; Shepherd, D.A.; Griffin, D. A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, G.G.; Grønhaug, K. Positive illusions and new venture creation: Conceptual issues and an empirical illustration. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2005, 14, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Houghton, S.M.; Aquino, K. Cognitive biases, risk perception, and venture formation: How individuals decide to start companies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Stevens, C.E.; Potter, D.R. Misfortunes or mistakes?: Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J. Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 604–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Lerner, D.A. The dark triad and nascent entrepreneurship: An examination of unproductive versus productive entrepreneurial motives. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, A. Towards increased regional specialization? the quantitative importance of new industrial spaces in norway, 1970–1990. Nor. Geol. Tidsskr. 1996, 50, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littunen, H.; Storhammar, E.; Nenonen, T. The survival of firms over the critical first 3 years and the local environment. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1998, 10, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilling, O.R. Regional variation of new firm formation: The Norwegian case. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1996, 8, 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, Y.; Lafuente, E. Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2007, 19, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelprang, A.W.; Habermann, M.; Swink, M. How firm innovativeness and unexpected product reliability failures affect profitability. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 38, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Folta, T.B. A comparison of the effect of angels and venture capitalists on innovation and value creation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, F.; Orlady, H. Human Factors in Flight; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, E.G.; Lee, M.S.; Suh, D.C. Who done it? Attributions by entrepreneurs and experts of the factors that cause and impede small business success. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2004, 42, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Khelil, N. Exploring the different patterns of entrepreneurial exit: The causes and consequences. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual International Council for Small Business World Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 11–14 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khelil, N. The many faces of entrepreneurial failure: Insights from an empirical taxonomy. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.C.; Gimeno-Gascon, F.J.; Woo, C.Y. Initial human and financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1994, 9, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlqvist, J.; Davidsson, P.; Wiklund, J. Initial conditions as predictors of new venture performance: A replication and extension of the cooper et al. study. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2000, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Brixy, U.; Falck, O. The effect of industry, region, and time on new business survival—A multi-dimensional analysis. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2006, 28, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, S.; Amit, R. Comprendre l’échec: Mortalité Organisationnelle et Approche Fondée sur les Ressources; Statistique Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003.

- Van Gelderen, M.; Thurik, R.; Bosma, N. Success and risk factors in the pre-startup phase. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesneau, D.A.; Gartner, W.B. A profile of new venture success and failure in an emerging industry. J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; McNamara, G. Publishing in AMJ—Part 2: Research Design. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autopsyio. Lessons from Failed Startups. Available online: http://autopsy.io (accessed on 3 August 2016).

- Van Gelderen, M.; Thurik, R.; Patel, P. Encountered problems and outcome status in nascent entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.B. A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, F. Human Factors in Flight, 2nd ed.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, R. Basic Flight Physiology, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Club Academy. Information to Maritime Administrations and Training Providers. Maritime Resource Management; A Brief Guide on the STCW Manila Amendments in Respect of Resource Management and Leadership & Teamwork Training; The Swedish Club Academy: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, F.E. Management Guide to Loss Control; Institute Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann, D.; Shappell, S. A Human Error Approach to Aviation Accident Analysis: The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System; England Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- EuroControl EAM 2/GUI 8. Guidelines on the Systemic Occurrence Analysis Methodology (SOAM); EuroControl: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Accident Investigator’s International Forum. 2000. Available online: http://www.maiif.org/imo (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation. A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. Business model, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirky, C. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- CBInsights. The Top 20 Reasons Startups Fail. From Lack of Product-Market Fit to Disharmony on the Team, We Break Down the Top 20 Reasons for Startup Failure by Analyzing 101 Startup Failure Post-Mortem. 2016. Available online: https://www.cbinsights.com/ (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- CBInsights. 166 Startup Failure Post-Mortems. 2016. Available online: https://www.cbinsights.com/blog/startup-failure-post-mortem/ (accessed on 28 July 2016).

- Blank, S. The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products That Win; BookBaby: Pennsauken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marsland, S. Machine Learning: An Algorithmic Perspective; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hidber, C. Online association rule mining. In Proceedings of the 1999 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 31 May–3 June 1999; Delis, A., Faloutsos, C., Ghandeharizadeh, S., Eds.; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 28, pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Perboli, G.; Ferrero, F.; Musso, S.; Vesco, A. Business models and tariff simulation in car-sharing services. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Musso, S.; Rosano, M.; Tadei, R.; Godel, M. Synchro-modality and slow steaming: New business perspectives in freight transportation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The GUEST Initiative. 2017. Available online: http://www.theguestmethod.com (accessed on 20 April 2017).

| Sector | Industry | Number of Industries | Sector | Industry | Number of Industries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICT and Telecomm. | Analitycs/Big Data | 8 | Entertainment and Education | E-book | 2 |

| Cloud Management | 2 | E-Learn | 3 | ||

| Hardware | 3 | Ed-Tech | 1 | ||

| Mobile | 8 | Entertainment | 15 | ||

| Telecomm. | 1 | Fashion | 6 | ||

| Web Development | 8 | Gaming | 6 | ||

| Software | 19 | Media | 7 | ||

| Platform | 6 | Music/Audio | 9 | ||

| Healthcare and Biotech | Biotech | 2 | News | 3 | |

| Healthcare IT and services | 4 | Photo/Video | 9 | ||

| Services | Advertising | 5 | Social Media | 27 | |

| Communications | 4 | Travel | 3 | ||

| Consultancy | 3 | Food and Grocery | Food & Grocery | 2 | |

| CRM | 3 | Manufacturing and Logistics | Logistic/ Delivery | 1 | |

| Energy | 4 | Commerce and Finance | Bitcoin | 2 | |

| Marketing | 2 | E-commerce | 12 | ||

| Security | 2 | Finance | 3 | ||

| Service | 17 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cantamessa, M.; Gatteschi, V.; Perboli, G.; Rosano, M. Startups’ Roads to Failure. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072346

Cantamessa M, Gatteschi V, Perboli G, Rosano M. Startups’ Roads to Failure. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072346

Chicago/Turabian StyleCantamessa, Marco, Valentina Gatteschi, Guido Perboli, and Mariangela Rosano. 2018. "Startups’ Roads to Failure" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072346

APA StyleCantamessa, M., Gatteschi, V., Perboli, G., & Rosano, M. (2018). Startups’ Roads to Failure. Sustainability, 10(7), 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072346