Size of Membership and Survival Patterns of Producers’ Organizations in Agriculture—Social Aspects Based on Evidence from Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

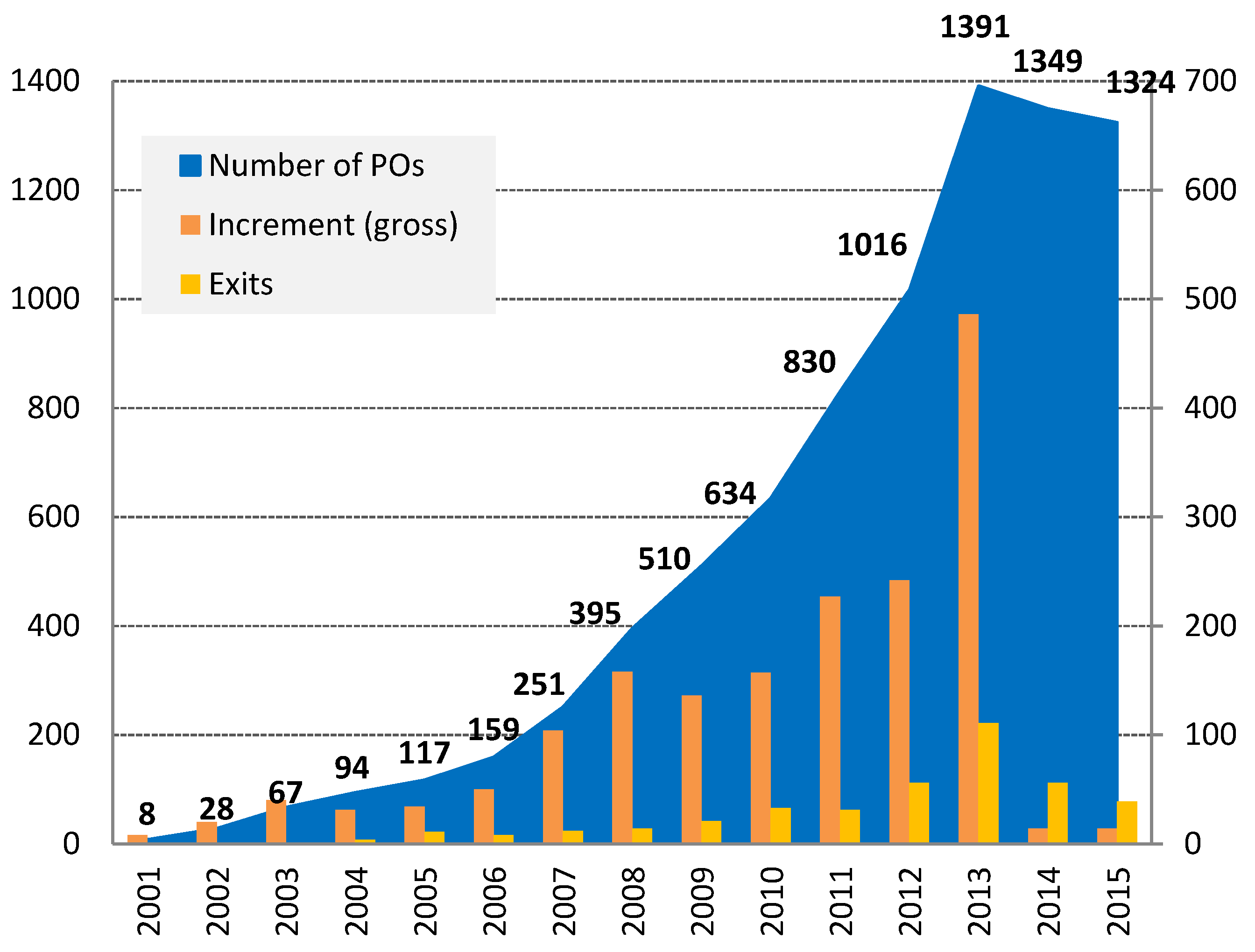

2. Study Background: Polish Experiences in Re-Establishing Farmers’ Cooperation

3. Theoretical Background

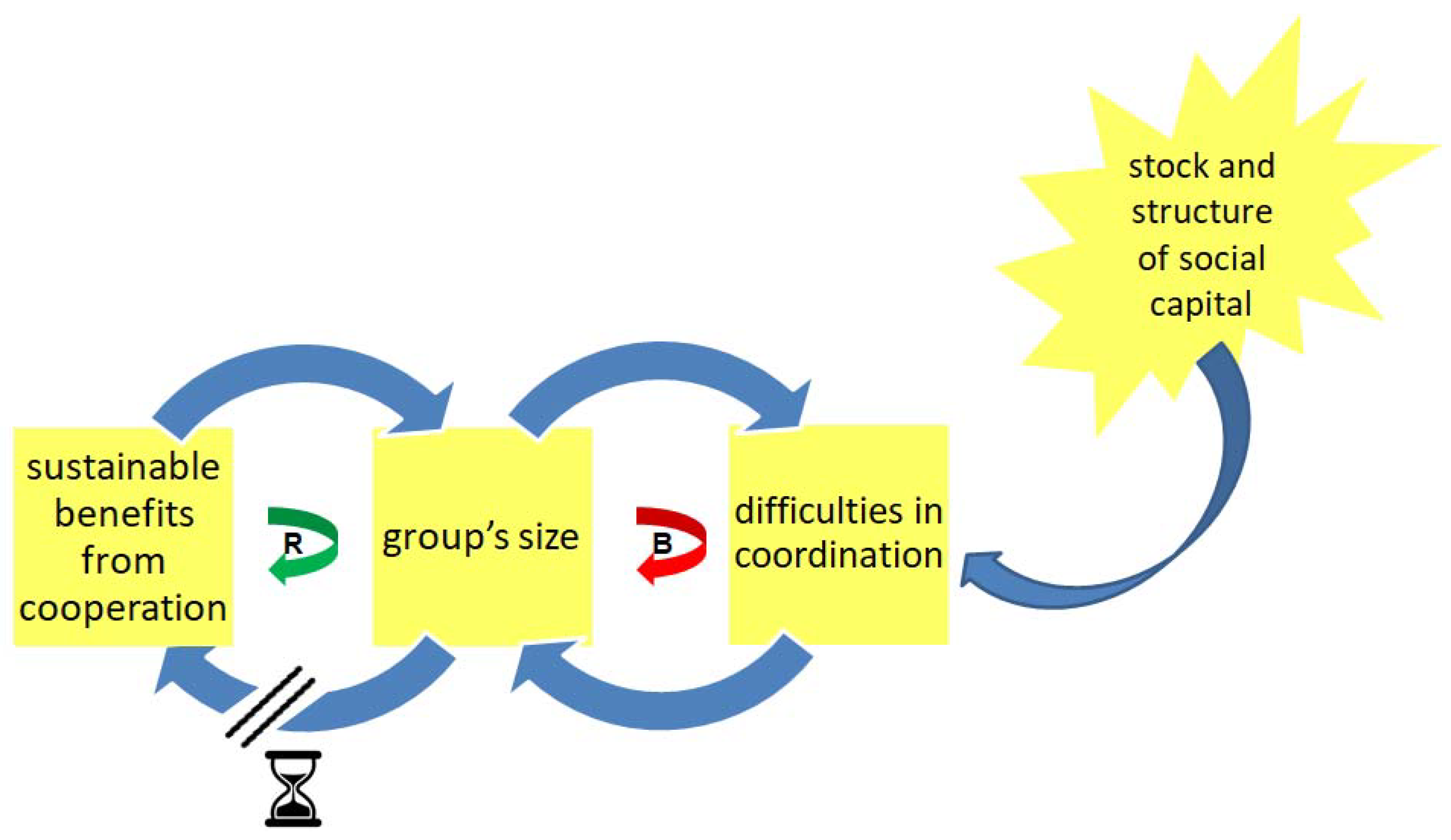

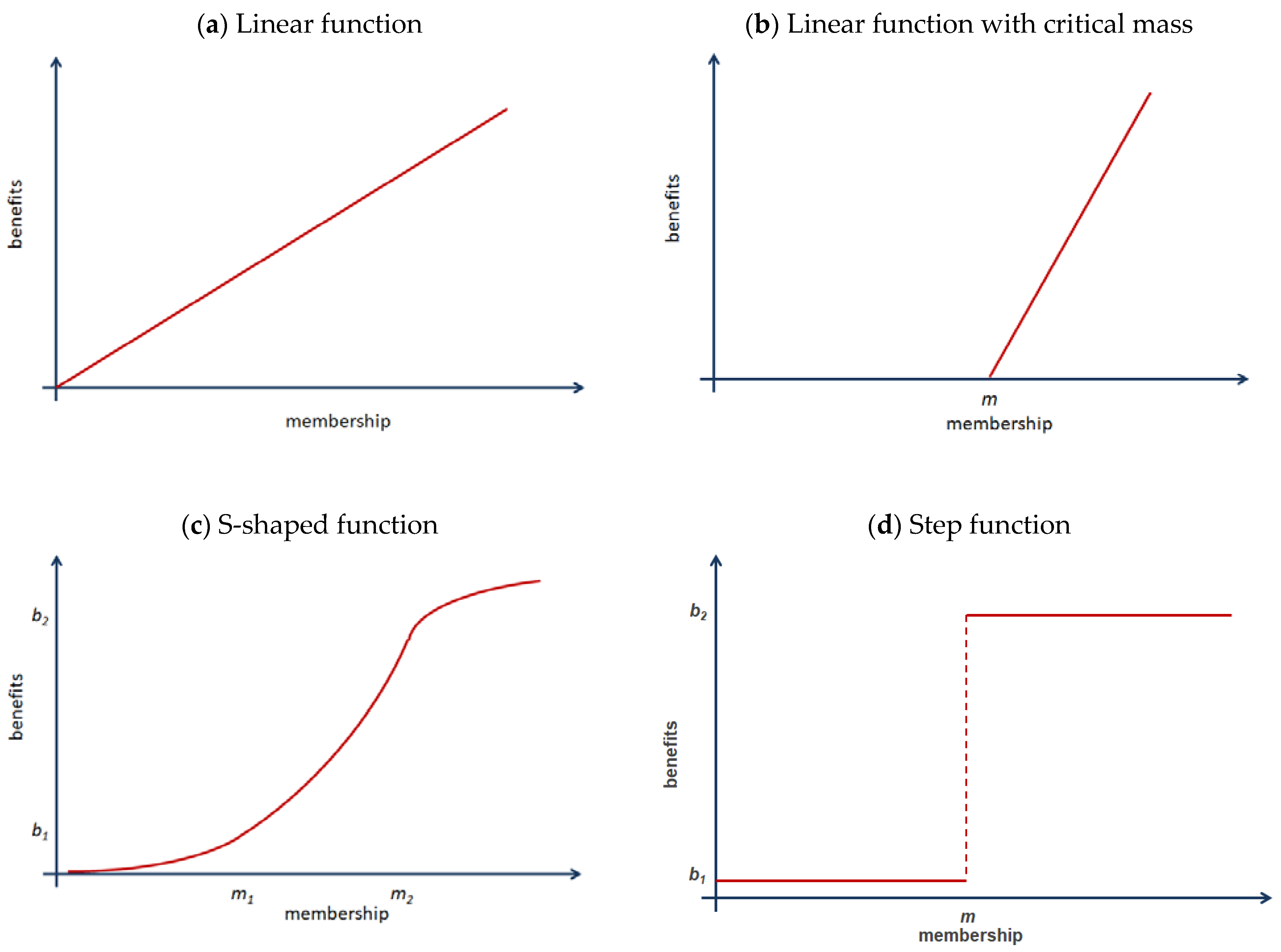

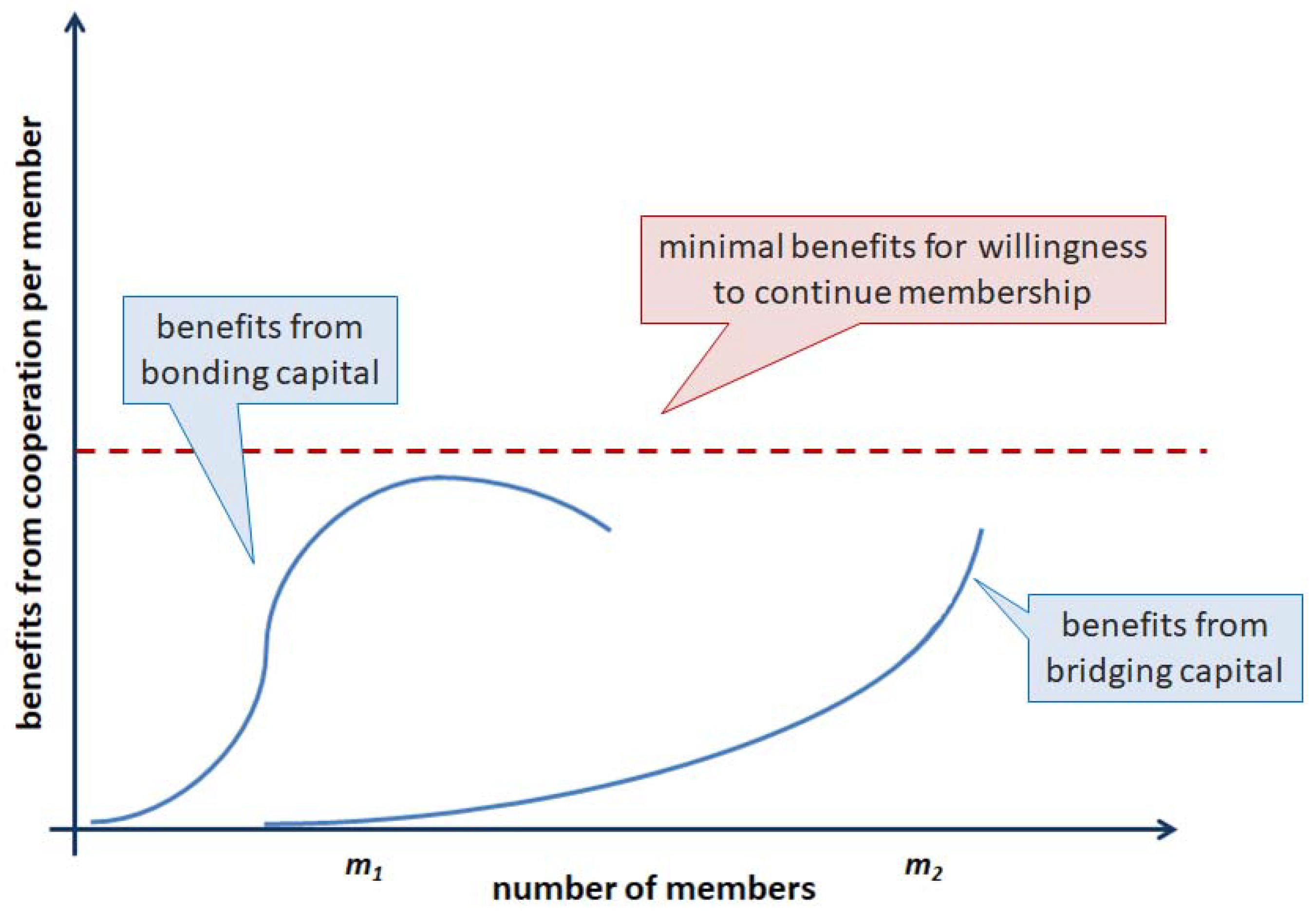

3.1. Importance of Social Capital for the Setting-Up and Functioning of POs

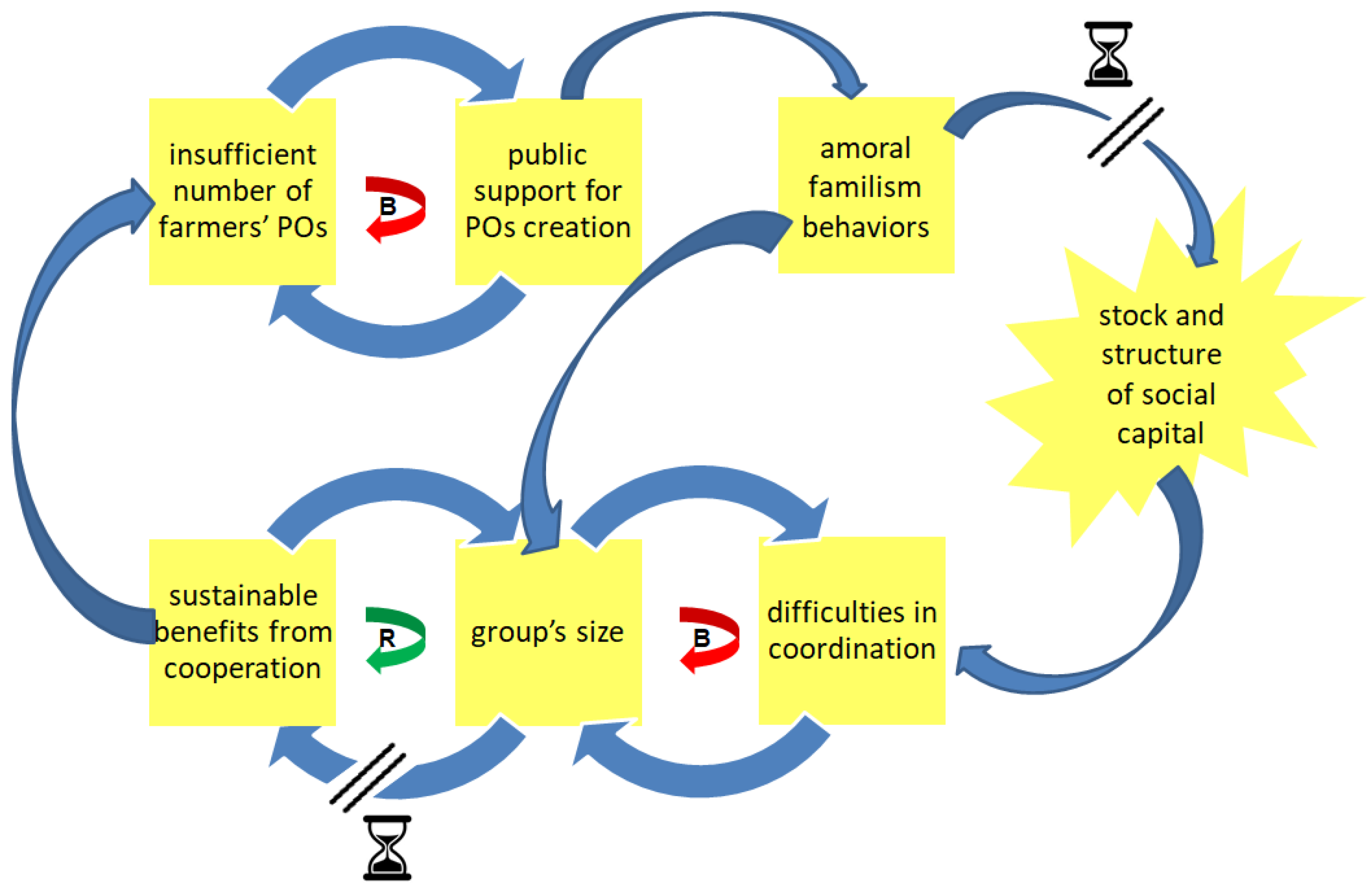

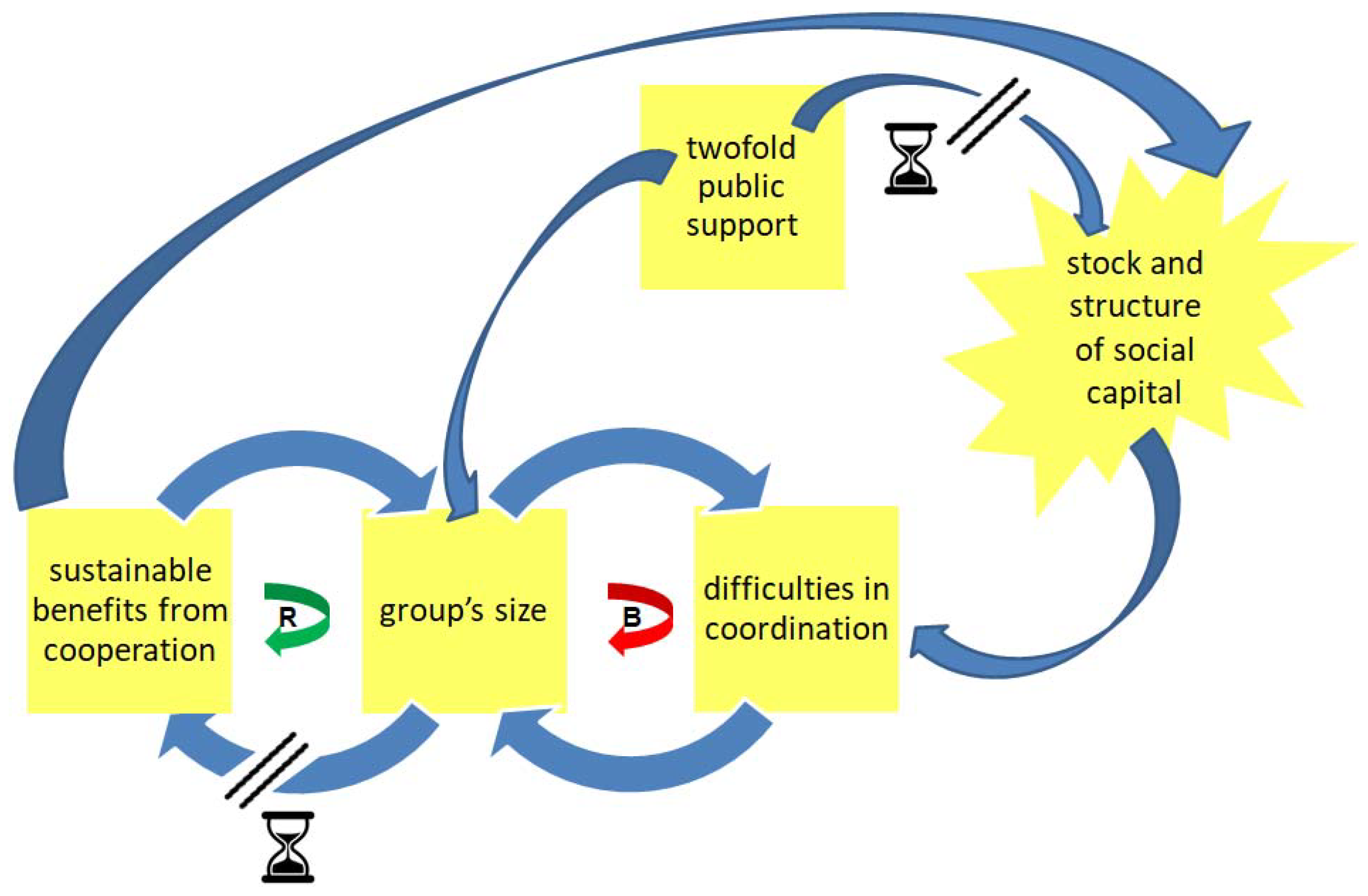

3.2. Systems Approach to Dynamic Complexity

3.3. Research Gap

4. Research Design, Data, and Methods

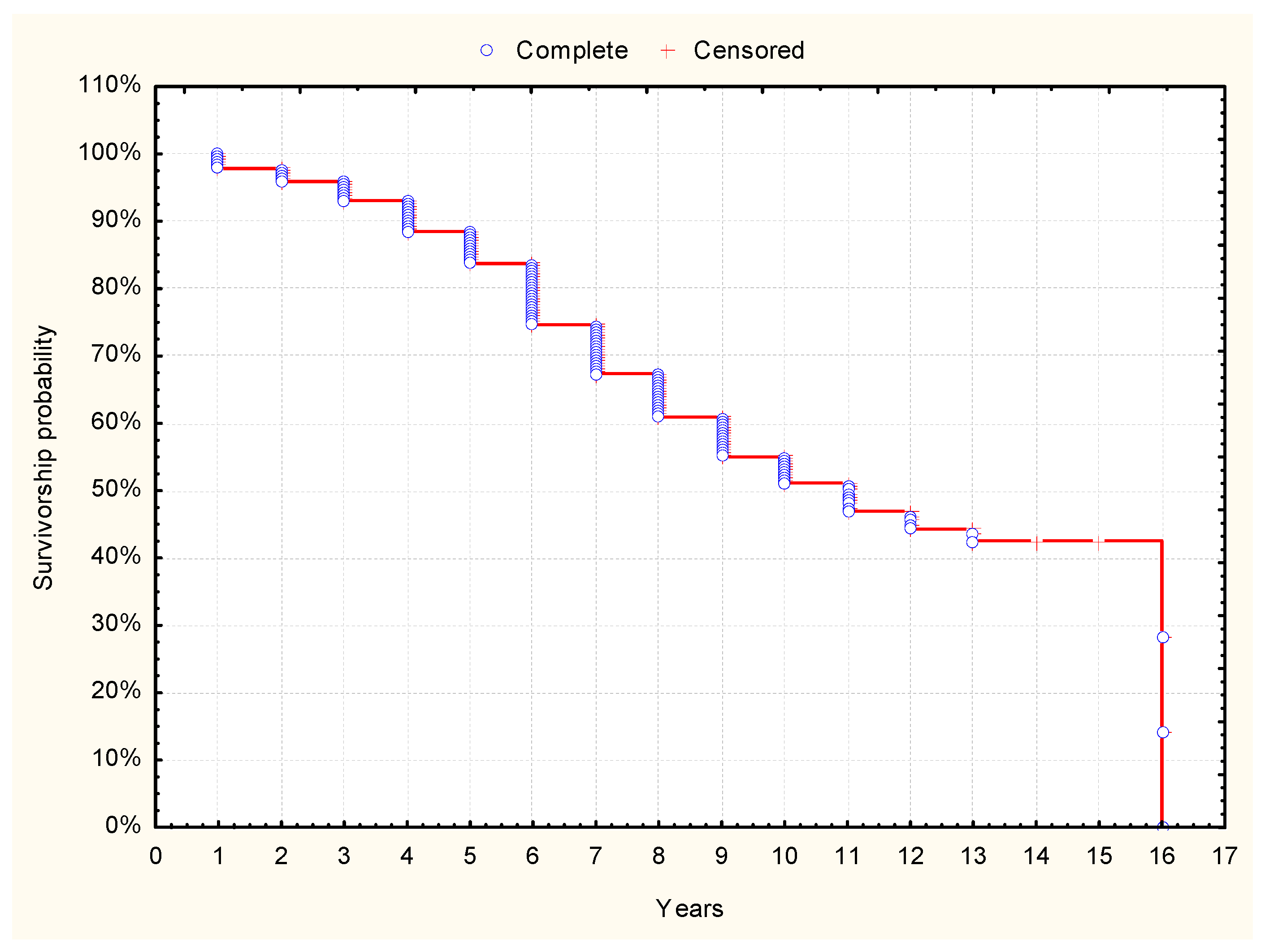

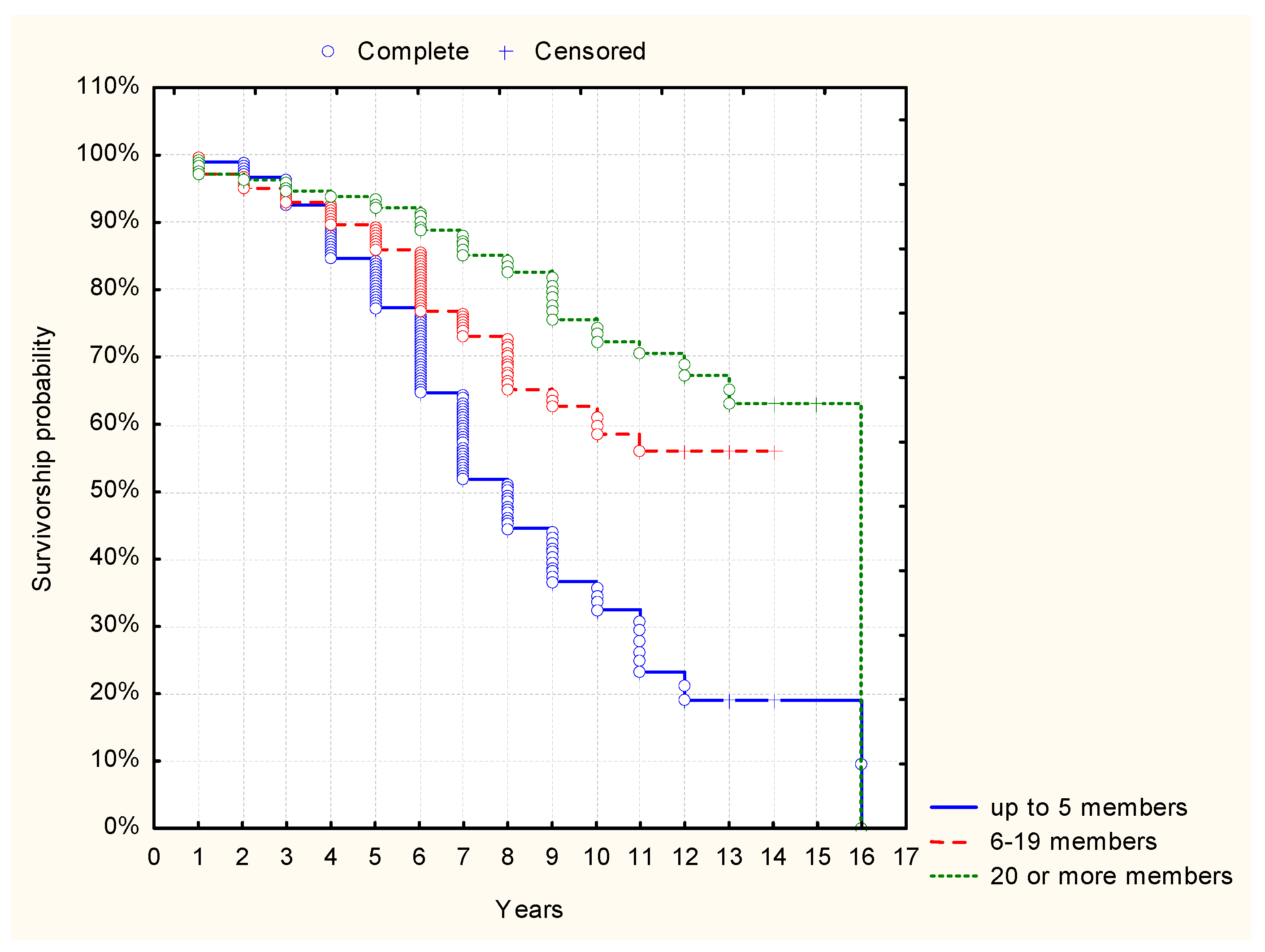

5. Results

- In my neighborhood, people generally trust each other (we called this proxy generalized trust);

- In my neighborhood, people are generally eager to cooperate (we called this proxy generalized attitude to cooperate).

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sexton, R.J. Market power, misconceptions, and modern agricultural markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, I.; Sperling, R. Estimating the Extent of Imperfect Competition in the Food Industry: What Have We Learned? J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 54, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perekhozhuk, O.; Glauben, T.; Grings, M.; Teuber, R. Approaches and Methods for the Econometric Analysis of Market Power: A Survey and Empirical Comparison. J. Econ. Surv. 2017, 3, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fałkowski, J.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D. Farmers’ selfreported bargaining power and price heterogeneity: Evidence from the dairy supply chain. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1672–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J.; Iliopoulos, C.; Poppe, K.J.; Gijselinckx, C.; Hagedorn, K.; Hanisch, M.; Hendrikse, G.W.J.; Kühl, R.; Ollila, P.; Pyykkönen, P.; et al. Support for Farmers’ Cooperatives; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Herck, K. Assessing Efficiencies Generated by Agricultural Producer Organisations; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2014; ISBN 978-92-79-39284-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikse, G.W.J.; Bijman, J. On the emergence of new growers’ associations: Self-selection versus market power. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2002, 29, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, C. Cooperatives: Hierarchies or Hybrids? In Vertical Markets and Cooperative Hierarchies. The Role of Cooperatives in the Agri-Food Industry; Karantininis, K., Nillson, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–17. ISBN 1-4020-4072-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chlebicka, A.; Fałkowski, J.; Wołek, T. Powstawanie grup producentów rolnych a zmienność cen. Zagadnienia Ekonomiki Rolnej 2009, 319, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fałkowski, J.; Ciaian, P. Factors Supporting the Development of Producer Organizations and Their Impacts in the Light of Ongoing Changes in Food Supply Chains; JRC Technical Reports; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chlebicka, A. Producer Organizations in Agriculture—Barriers and Incentives of Establishment on the Polish Case. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Statistics; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-79-75765-5. [Google Scholar]

- Boselie, D.; Henson, S.; Weatherspoon, D. Supermarket procurement practices in developing countries: Redefining the roles of the public and private sectors. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 5, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi. Strategy for Sustainable Development of Rural Areas, Agriculture and Fisheries for 2012–2020; Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi: Warsaw, Poland, 2012.

- Chloupkova, J. Polish Agriculture: Organisational Structure and Impacts of Transition; Unit of Economics Working Papers 2002/3; Food and Resource Economic Institute, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; pp. 1–23. Available online: file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Microsoft/Windows/Temporary%20Internet%20Files/Content.IE5/3RDMNOFX/ew020003.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Gardner, B.; Lermann, Z. Agricultural Cooperative Enterprise in the Transition from Socialist Collective Farming. J. Rural Coop. 2006, 34, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chloupkova, J.; Svendsen, G.H.L.; Svendsen, G.T. Building and Destroying Social Capital: The Case of Cooperative movements in Denmark and Poland. Agric. Hum. Values 2003, 20, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J. Changes in agricultural land ownership in Poland in the period of the market economy. Agric. Econ. 2011, 57, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, D. The Collectivization of Agriculture in Poland. In The Collectivization of Agriculture in Communist Eastern Europe Comparison and Entanglements; Iordachi, C., Bauerkamper, A., Eds.; Central European University Press: Budapest, Hungary, 2014; pp. 113–146. ISBN 978-615-5225-63-5. [Google Scholar]

- Boguta, W. Działalność Spółdzielni Rolniczych ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Zarządzania Spółdzielnią Oraz Prowadzenia Działalności Finansowej i Marketingowej; Krajowa Rada Spółdzielcza: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Domagalski, A. Organizowanie się Gospodarcze Polskich Rolników po 1990 Roku; Krajowa Rada Spółdzielcza: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Matczak, P. Support for Farmers’ Cooperatives; Country Report Poland; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Knack, S.; Keefer, P. Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Social capital: A fad or a fundamental concept? In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Serageldin, I., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 172–214. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R. The Contingent Value of Social Capital. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory of Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; ISBN 9780674312265. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780691037387. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 8601400226735. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 0684825252. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Social Capital and Civil Society (April 2000). IMF Working Paper 2000. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=879582 (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Burt, R. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0199249156. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Prusak, L. Good Company: How Social Capital Makes Organizations Work; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 9780875849133. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, M.; Benassi, M. Trapped in Your Own Net? Network Cohesion, Structural Holes, and the Adaptation of Social Capital. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 9780674843714. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital and Value Creation: The Role of Intrafirm Networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.-W. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, G.L.H.; Svendsen, G.T. The Creation and Destruction of Social Capital: Entrepreneurship, Cooperative Movements and Institutions; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; ISBN 1-84376-616-7. [Google Scholar]

- Halamska, M. Społeczna kondycja polskiej wsi. Struktura, kapitały i społeczeństwo obywatelskie w I dekadzie XXI wieku. In Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich w Polsce. Diagnozy, Strategie, Koncepcje Polityki; Nurzyńska, I., Drygas, M., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wieruszewska, M. Społeczność wiejska—Podstawy samoorganizacji. In Samoorganizacja w Społecznościach Wiejskich: Przejawy, Struktury, Zróżnicowania; Wieruszewska, M., Ed.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2002; pp. 12–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyszak-Radziejowska, B. Kapitał społeczny wsi—W poszukiwaniu utraconego zaufania. In Kapitał Ludzki i Zasoby Społeczne wsi. Ludzie—Społeczność Lokalna—Edukacja; Szafraniec, K., Ed.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2006; pp. 71–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, D.W. The Transition: Evaluating the Postcommunist Experience; Aldershot: Hants, UK, 2002; ISBN 0754630617, 9780754630616. [Google Scholar]

- Paldam, M.; Svendsen, G.T. An essay on social capital: Looking for the fire behind the smoke. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2000, 16, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidrmuc, J.; Gërxhani, K. Mind the Gap! Social Capital, East and West. J. Comp. Econ. 2008, 36, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turowski, J. Socjologia wsi i Rolnictwa; Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL: Lublin, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bondyra, K. Kooperacja a przemiany na wsi. Wieś i Rolnictwo 2003, 3, 350–356. [Google Scholar]

- De Master, K. Designing Dreams or Constructing Contradictions? European Union Multifunctional Policies and the Polish Organic Farm Sector. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalewska-Pawlak, M. Możliwości i bariery rozwoju kapitału społecznego na obszarach wiejskich w Polsce. In Kapitał Społeczny—Interpretacje, Impresje, Operacjonalizacja; Klimowicz, M., Bokajło, W., Eds.; CeDeWu Sp. z o.o.: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Random House Business Books: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9781905211203. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikse, G.W.J.; Veerman, C.P. Marketing Cooperatives and Financial Structure: A Transaction Costs Economics Analysis. Agric. Econ. 2001, 26, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, I. Success and Failure of Cooperation in Agricultural Markets. Evidence from Producer Groups in Poland; Shaker Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3-8322-6995-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chlebicka, A.; Fałkowski, J.; Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk, B. Grupy producentów rolnych a kapitał społeczny—Potencjalne zależności. Wieś i Rolnictwo 2014, 164, 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. How types of goods and property rights jointly affect collective action. J. Ther. Politics 2003, 15, 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.; Marwell, G.; Teizeira, R. A Theory of the Critical Mass. I. Interdependence, Group Heterogenity, and the Production of Collective Action. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 522–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. The Number of Members as Determining the Sociological Form of the Group. II. Am. J. Sociol. 1902, 8, 158–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Co-Operation; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0300188288. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka, P. Socjologia; Wydawnictwo Znak: Kraków, Poland, 2007; ISBN 978-83-240-0218-4. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action. Public Goods and the Theory of the Groups; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; ISBN 0-674-53751-3. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, R.A. The Theory of Public Finance; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959; ISBN 978-0070855311. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-521-40599-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, C.I. The Functions of the Executive; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; ISBN 978-0674328037. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, R.W. Management; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-618-83345-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fałkowski, J.; Chlebicka, A.; Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk, B. Social relationships and governing collaborative actions in rural areas: Some evidence from agricultural producer groups in Poland. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 49, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V. Social Capital, Transition in Agriculture, and Economic Organisation: A Theoretical Perspective; IAMO Discussion Paper; Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies (IAMO): Halle, Germany, 2003; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov, V. Toward a Social Capital Theory of Co-operative Organisation. J. Coop. Stud. 2004, 37, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, M. Cooperatives and member commitment. Finn. J. Bus. Econ. 1999, 4, 418–437. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.; Kihlen, A.; Norell, L. Are Traditional Cooperatives an Endangered Species? About Shrinking Satisfaction, Involvement and Trust. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2009, 12, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, G.G. The importance and role of trust in agricultural marketing co-operatives. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2010, 112, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Möllers, J.; Traikova, D.; Bîrhală, B.; Wolz, A. Why (not) cooperate? A cognitive model of farmers’ intention to join producer groups in Romania. Post-Communist Econ. 2017, 30, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebicka, A.; Fałkowski, J.; Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk, B. Horizontal integration between farmers governing cooperation through different enforcement mechanisms. In It’s a Jungle Out There—The Strange Animals of Economic Organization in Agri-Food Value Chains; Martino, G., Karantininis, K., Pascucci, S., Dries, L., Codron, J.M., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 85–104. ISBN 978-90-8686-301-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J.; Svendsen, G.L.H.; Svendsen, T.G. Are large and complex agricultural cooperatives losing their social capital? Agribusiness 2012, 28, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G.J. The Economies of Scale. J. Law Econ. 1958, 1, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, D.W.; Perloff, J.M. Modern Industrial Organization; Pearson Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-321-22341-1. [Google Scholar]

- Saving, T.R. Estimation of Optimum Size of Plant by the Survivor Technique. Q. J. Econ. 1961, 75, 569–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.W. The Survival Technique and the Extent of Suboptimal Capacity. J. Political Econ. 1964, 72, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.P. The Minimum Optimal Steel Plant and the Survivor Technique of Cost Estimation. Working Paper No. 197; 1992. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/minimum-optimal-steel-plant-and-survivor-technique-cost-estimation/wp197.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Scherer, F.M. Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance; Rand McNally College Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gijselnickx, C.; Bussels, M. Farmers’ cooperatives in Europe: Social and historical determinants of cooperative membership in agriculture. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2014, 85, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, K. Post-socialist farmers’ cooperatives in Central and Eastern Europe. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2014, 85, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.L.; Burress, M.J. A Cooperative Life Cycle Framework. Available online: http://departments.agri.huji.ac.il/economics/en/events/p-cook.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2017).

- Forrester, J.W. Counterintuitive Behavior of Social Systems. Available online: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/sloan-school-of-management/15-988-system-dynamics-self-study-fall-1998-spring-1999/readings/behavior.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Strategy Maps. Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 1-59139-134-2. [Google Scholar]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. The Future of Food and Farming (COM/2017/0713 Final). Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/03dc8701-d5aa-11e7-a5b9-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Michalek, J.; Ciaian, P.; Pokrivcak, J. The impact of producer organizations on farm performance: The case study of large farms from Slovakia. Food Policy 2018, 75, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups Differences | Log-Rank Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Small versus medium | 5.317359 | 0.00000 |

| Small versus the biggest | 8.161482 | 0.00000 |

| Medium versus the biggest | 3.001920 | 0.00268 |

| Family Bonds with Other Members | Sum of the Rows | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Categories | None at All | Yes | |

| Size of a PO | Up to Median | 28 | 57 | 85 |

| Percent of Total | 17.610% | 35.849% | 53.459% | |

| Above Median | 41 | 33 | 74 | |

| Percent of Total | 25.786% | 20.755% | 46.541% | |

| Sum of the Column | 69 | 90 | 159 | |

| Sum of Percentages | 43.396% | 56.604% | 100% | |

| χ2: 8.13 | p-value: 0.0044 | |||

| Acquaintance Relationships with Other Members | Sum of the Rows | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Categories | None at All | Yes | |

| Size of a PO | Up to Median | 13 | 79 | 92 |

| Percent of Total | 7.386% | 44.886% | 52.273% | |

| Above Median | 3 | 81 | 84 | |

| Percent of Total | 1.705% | 46.023% | 47.727% | |

| Sum of the Column | 16 | 160 | 176 | |

| Sum of Percentages | 9.091% | 90.909% | 100% | |

| χ2: 5.92 | p-value: 0.0149 | |||

| Generalized Trust | Sum of the Rows | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Categories | Low | High | |

| Size of a PO | Up to Median | 32 | 40 | 72 |

| Percent of Total | 24.427% | 30.534% | 54.962% | |

| Above Median | 12 | 47 | 59 | |

| Percent of Total | 9.160% | 35.878% | 45.038% | |

| Sum of the Column | 44 | 87 | 131 | |

| Sum of Percentages | 33.588% | 66.412% | 100% | |

| χ2: 8.45 | p-value: 0.0037 | |||

| Generalized Attitude towards Cooperation | Sum of the Rows | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Categories | Low | High | |

| Size of a PO | Up to Median | 35 | 46 | 81 |

| Percent of Total | 23.026% | 30.263% | 53.289% | |

| Above Median | 11 | 60 | 71 | |

| Percent of Total | 7.237% | 39.474% | 46.711% | |

| Sum of the column | 46 | 106 | 152 | |

| Sum of percentages | 30.263% | 69.737% | 69.737% | |

| χ2: 13.77 | p-value: 0.0002 | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chlebicka, A.; Pietrzak, M. Size of Membership and Survival Patterns of Producers’ Organizations in Agriculture—Social Aspects Based on Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072293

Chlebicka A, Pietrzak M. Size of Membership and Survival Patterns of Producers’ Organizations in Agriculture—Social Aspects Based on Evidence from Poland. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072293

Chicago/Turabian StyleChlebicka, Aleksandra, and Michał Pietrzak. 2018. "Size of Membership and Survival Patterns of Producers’ Organizations in Agriculture—Social Aspects Based on Evidence from Poland" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072293

APA StyleChlebicka, A., & Pietrzak, M. (2018). Size of Membership and Survival Patterns of Producers’ Organizations in Agriculture—Social Aspects Based on Evidence from Poland. Sustainability, 10(7), 2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072293