How to Build Consumer Trust: Socially Responsible or Controversial Advertising

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Advertising in the Modern World

2.2. Framing Corporate Social Responsibility

2.3. How Advertising Fits into CSR

2.4. Developing Hypotheses: When Controversy Enters Advertising

- Motives and associations referring to eroticism (characters who are above-average in physical attractiveness, nude images, explicitly showing or implying kisses or sexual intercourse, referring to homosexual acts, implying erotic meaning through symbols, humor or word-play).

- Images of well-known, controversial persons or celebrities presented in a controversial manner.

- Content which is shocking in terms of graphics or sound (drastic scenes, violence, cruelty, death or rape motives).

- Associations of a religious, racial or ethnic nature.

- Human figures presented in a way which implies or maintains negative stereotyping of specific social groups (women, men, children, or elderly people).

- Information whose accuracy is clearly doubtful (misleading advertising).

- Addressing children in a way which exploits their simple-mindedness and lack of market experience.

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

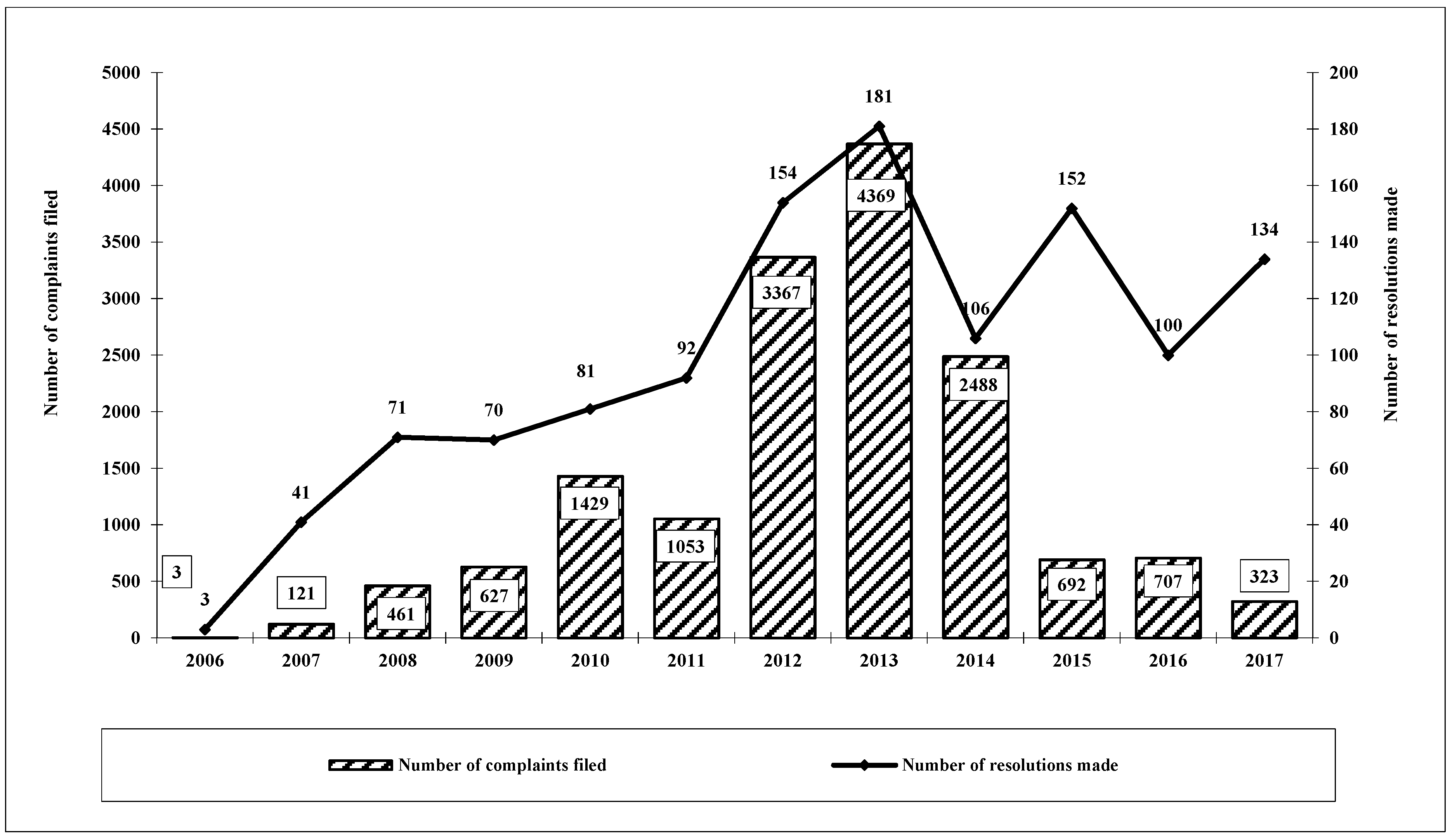

4.1. Organizational Perspective

4.2. Customer Perspective

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, J.; Hustvedt, G. Building Trust between Consumers and Corporations: The Role of Consumer Perceptions of Transparency and Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, F.-R.; Langner, T.; Schmitt, B.H.; Geus, P. Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2006, 15, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S.; Yao, J.L. Reviving brand loyalty: A reconceptualization within the framework of consumer-brand relationships. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1997, 14, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment—Trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Aleman, J.L.; Yague-Guillen, M.J. Development and validation of a brand trust scale. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 45, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ranaweera, C.; Prabhu, J. The influence of satisfaction, trust and switching barriers on customer retention in a continuous purchasing setting. J. Serv. Manag. 2003, 14, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, M. Citizen brands: Corporate citizenship, trust and branding. J. Brand Manag. 2003, 10, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer Trust, Value, and Loyalty in Relational Exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.G.; Manika, D.; Stout, P. Causes and consequences of trust in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 216–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, F. Brand Credibility, Brand Consideration, and Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L.L.; Wisenblit, J. Consumer behavior. In Global Edition, 10th ed.; Prentice Hall: Pearson, GA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Miniard, P.W. On the Potential For Advertising to Facilitate Trust in the Advertised Brand. J. Advert. 2006, 35, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaniz, E.B.; Caceres, R.C.; Perez, R.C. Alliances between brands and social causes: The influence of company credibility on social responsibility image. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, H.; Reid, L.N.; Whitehill-King, K. Measuring Trust in Advertising: Development and Validation of the ADTRUST Scale. J. Advert. 2013, 38, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, H.; Reid, L.N.; Whitehill-King, K. Trust in Different Advertising Media. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2007, 84, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, W.F.; Schaefer, D.H.; Weigold, M. Essentials of Contemporary Advertising, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, A.; Barnard, J.; Hutcheon, N. Advertising Expenditure Forecasts September 2016, Zenith, London, 2016. Available online: http://zenithmedia.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Advertising-Expenditure-Forecasts-September-2016.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Pallus, P. Advertising in the World Is Accelerating. In Poland Its Increase Slightly Inhibits. Available online: http://businessinsider.com.pl/media/rynek-reklamy-w-2016-roku-w-polsce-i-na-swiecie/fxrt3mw (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Elliott, R.; Jones, A.; Benfield, A.; Barlow, M. Overt sexuality in advertising: A discourse analysis of gender responses. J. Consum. Policy 1995, 18, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, K.S.; Waller, D.S.; Yang, Z. Addressing the advertising of controversial products in China: An empirical approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrieri, L.; Brace-Govan, J.; Cherrier, H. Controversial advertising: Transgressing the taboo of gender-based violence. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1448–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.; Mortimer, K.; Dickinson, S.; Waller, D.S. Buy, boycott or blog. Exploring online consumer power to share, discuss and distribute controversial advertising messages. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, B.; Lassar, W.M. Sexual liberalism as a determinant of consumer response to sex in advertising. J. Bus. Psychol. 2000, 15, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.; Golan, G.J. From subservient chickens to brawny men: A comparison of viral advertising to television advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2006, 6, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, D.S.; Fam, K.-S.; Erdogan, B.Z. Advertising of controversial products: A cross-cultural study. J. Consum. Mark. 2005, 22, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, R.A. Advertising and product responsibility. Bus. Soc. 1966, 7, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Crit. Sociol. 2008, 34, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D. Corporate citizenship: Rethinking business beyond corporate social responsibility. In Perspectives on Corporate Citizenship; Andriof, J., McIntosh, M., Eds.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. (Ed.) Managing Corporate Social Responsibility; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, R.B.; Hackett, R.D. The assessment of individual moral goodness. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, K. Corporate citizenship: A stakeholder approach for defining corporate social performance and identifying measures for assessing it. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooks, G.; Gilmore, A.; Collin, J.; Holden, C.; Lee, K. The limits of corporate social responsibility: Techniques of neutralization, stakeholder management and political CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frynas, J.G.; Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 258–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.L. Executive perceptions of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 1976, 19, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, G.A. Social policies for business. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1972, 15, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wines, W.A. Seven pillars of business ethics: Toward a comprehensive framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Bezares, F.; Przychodzen, W.; Przychodzen, J. Bridging the gap: How sustainable development can help companies create shareholder value and improve financial performance. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brei, V.; Böhm, S. Corporate social responsibility as cultural meaning management: A critique of the marketing of ‘ethical’ bottled water. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2011, 20, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. The virtue matrix: Calculating the return on corporate responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robin, D. Toward an applied meaning for ethics in business. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Michelini, L.; Fiorentino, D. New business models for creating shared value. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, S.; Sarni, W. Does the concept of ‘creating shared value’ hold water? J. Bus. Strat. 2015, 36, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, K.; Doyle Corner, P. Conscious enterprise emergence: Shared value creation through expanded conscious awareness. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzeck, H.; Chapman, S. Creating shared value as a differentiation strategy—The example of BASF in Brazil. Corp. Gov. 2012, 12, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, D.; Berens, G.; Li, T. The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility communication on corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiyeh, S.; Kwarteng, A.; Ato Dadzie, S. Corporate social responsibility and reputation: Some empirical perspectives. J. Glob. Responsib. 2016, 7, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Sánchez, J.L.; Luna Sotorrío, L.; Baraibar Diez, E. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation in a turbulent environment: Spanish evidence of the Ibex35 firms. Corp. Gov. 2015, 15, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Abeysekera, I.; Cortese, C. Corporate social responsibility reporting quality, board characteristics and corporate social reputation Evidence from China. Pac. Account. Rev. 2015, 27, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Thorne, D.M.; Ferrell, L. Social Responsibility and Business, 4th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. The double bottom line: Profit and social benefit. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griseri, P.; Seppala, N. Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S.P. Dimensions of corporate social performance: An analytical framework. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1975, 17, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P. A conceptual framework for environmental analysis of social issues and evaluation of business response patterns. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. From CSR 1 to CSR2: The maturing of business-and-society. Bus. Soc. 1994, 33, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenisek, T.J. Corporate social responsibility: A conceptualization based on organizational literature. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belch, G.E.; Belch, M.A. Advertising and Promotion. An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective; McGraw-Hill Book: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, W.L.; Wright, J.S.; Zeidler, S.K. Advertising; McGraw-Hill Book: New Delhi, India, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, R.; Strużycki, M. Advertising in Organizations; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jefkins, F. Advertising; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jachnis, A.; Terelak, J.F. Psychology of Consumer and Advertising; Oficyna Wydawnicza Branta: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski, A.; Tyszka, T. Psychology of Consumer Behavior; GWP: Gdansk, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Soscia, I.; Girolamo, S.; Busacca, B. The effect of comparative advertising on consumer perceptions: Similarity or differentiation? J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.-T. The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from the life insurance industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, R. Perception of advertising and its impact on consumers’ behavior in the first decade of 21th century. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Problemy Zarządzania, Finansów i Marketingu 2013, 32, 403–416. [Google Scholar]

- Te’eni-Harari, T. Clarifying the relationship between involvement variables and advertising effectiveness among young people. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 37, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, L.A. Ethics in Media Communication; Belmont: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Keh, H.T.; Peng, S. Effects of advertising strategy on consumer-brand relationships: A brand love perspective. Front. Bus. Res. China 2009, 3, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Roth, N.L. Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic “remedies” for trust/distrust. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Bruzzone, D.E. Causes of Irritation in Advertising. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.H.; Dotson, M.J. An Exploratory Investigation into the Nature of Offensive Television Advertising. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byramjee, F.; Batra, M.M.; Scudder, B.; Klein, A. Toward an ethical and legal framework for minimizing advertising violations. J. Acad. Bus. Econ. 2013, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, D.W.; Frankenberger, K.D.; Manchanda, R.V. Does it pay to Shock? Reactions to Shocking and Non-Shocking Ad Content among University Students. J. Advert. Res. 2003, 43, 268–280. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, B.; Yessel, J. Are Advertisers Practicing Safe Sex? Mark. News 1994, 28, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, A.; Fullerton, J.A.; Kim, Y.J. Social Responsibility in Advertising: A Marketing Communications Student Perspective. J. Mark. Educ. 2013, 35, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machova, R.; Seres-Huszarik, E.; Toth, Z. The role of shockvertising in the context of various generations. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2015, 13, 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mierzwińska-Hajnos, A. Shockvertising: Beyond Blunt Slogans and Drastic Images. A Conceptual Blending Analysis. Lub. Stud. Inmodern Lang. Lit. 2014, 38, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Ethics in Advertising: Review, Analysis, and Suggestions. J. Public Policy Mark. 1998, 17, 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, S.; Jones, R.; Stern, P.; Robinson, M. ‘Shockvertising’: An exploratory investigation into attitudinal variations and emotional reactions to shock advertising. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Sobrino, P. Shockvertising: Conceptual interaction patterns as constraints on advertising creativity. Circ. Lin Guist. Apl. Comun. 2016, 65, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, W.; Ibrahim, G.; Naja, M.; Hakam, N. Provocation in Advertising: The Attitude of Lebanese Consumers. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2015, 9, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Severin, J.; Belch, G.E.; Belch, M.A. The effects of sexual and nonsexual advertising appeals and information level on cognitive processing and communication effectiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezina, R.; Paul, O. Provocation in advertising: A conceptualization and an empirical assessment. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1997, 14, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparski, W. Business ethics—Sketches. In Business Ethics; Dietl, J., Gasparski, W., Eds.; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, M. Responsible ads: A workable ideal. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, I. Interaction of law and ethics in matters of advertisers’ responsibility for protecting consumers. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogalski, B.; Śniadecki, J. Managerial Ethics; OPO: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, N. Shockvertising—Method or madness. Abhinav-Natl. Mon. Refereed J. Res. Commer. Manag. 2013, 2, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, D.C.; Pitts, R.E.; Etzel, M.J. The communication effects of controversial sexual content in television programs and commercials. J. Advert. 1983, 12, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddewyn, J.J.; Kunz, H. Sex and decency issues in advertising: General and international dimensions. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Li, L.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R. Consumers’ response to offensive advertising: A cross cultural study. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 606–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, K.S.; Waller, D.S.; Ong, F.S.; Yang, Z. Controversial product advertising in China: Perceptions of three generational cohorts. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.; Weinberger, M.G.; Gulas, C.S. The Impact of Perceived Humor, Product Type, and Humor Style in Radio Advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2004, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, H.W. Sex stereotypes in advertisements. Bus. Soc. 1976, 17, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyser, S. Advertising attacks and counters. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1972, 36, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert, J. Advertising: Criticism and reply. Bus. Soc. 1968, 9, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Tour, M.S.; Zahra, S.A. Fear appels as advertising strategy: Should they by used? J. Serv. Mark. 1988, 2, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.; Hwa, H. An Asian perspective of offensive advertising on the web. Int. J. Advert. 2003, 22, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.; Cheung, W.-L.; West, D. How far is to fa? The antecedents of offensive advertising in modern China. J. Advert. Res. 2008, 48, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.L.; Wilkie, W.L. Fair: The potential of an appeal neglected by marketing. J. Mark. 1970, 34, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O.; Obermiller, C. Consumer perception of taboo in ads. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandikci, O. Shock tactics in advertising and implications for citizen-consumer. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 18, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal, B.; Craig, C.S. Humor in Advertising. J. Mark. 1973, 37, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaar, P.E.; Konig, R.; Smit, E.G.; Thorbjørnsen, H. In ads we trust. Religiousness as a predictor of advertising trustworthiness and avoidance. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurgin, E.W. What’s wrong with computer-generated images of perfection in advertising? J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 45, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, D.S.; Mitra, K. Ethical evaluation of marketing practices in tobacco industry. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 7, 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, N.K.; Pettijohn, C.E.; Burnett, M.S. Ethics in advertising: Differences in industry values and student perceptions. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2008, 12, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 26000—Social Responsibility 2014. Available online: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/iso26000.htm (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Nowacki, R. Poles’Attitudes towards Unethical Advertising Activities in the Light of Functioning of the Code of Ethics in Advertising. Handel Wewnętrzny 2016, 1, 290–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bachnik, K. Corporate social responsibility and the ethics in advertising. In Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific Conference Business and Management, Vilnius, Lithuania, 10–11 May 2012; Ginevicius, R., Rutkauskas, A.V., Stankeviciene, J., Eds.; Vilnius Gediminas Technical University: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bachnik, K. Organizational culture and implementation of CSR initiatives. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the New Economy; Płoszajski, P., Ed.; OpenLinks: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calfee, J.E.; Ringold, D.J. The 70% Majority: Enduring Consumer Beliefs about Advertising. J. Public Policy Mark. 1994, 13, 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, R.J. Affective and Cognitive Antecedents of Attitude toward the Ad: A Conceptual Model. In Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects; Alwitt, L.F., Mitchell, A.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, A.M.; Deshpande, A.D.; Zinkhan, G.M.; Perri, M. A Model of Assessing the Effectiveness of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising: Integration of Concepts and Measures from Marketing and Healthcare. Int. J. Advert. 2004, 23, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TOTAL | Sector | Enterprise Size | Range of Operations | Capital Structure | Market Position | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Trade | Services | Up to 9 Employees | 10 to 49 Employees | 50 to 249 Employees | Over 249 Employees | Local | Regional | National | International | Polish | Foreign/Mixed | Weak | Average | Strong | ||

| In recent years, controversy has been present in advertising more frequently | |||||||||||||||||

| I strongly disagree | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 1.5 |

| I disagree | 8.1 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 9.9 | 3.9 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 2.5 | 9.3 | 5.6 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 6.2 |

| Neutral | 25.9 | 28.7 | 26.2 | 19.5 | 24.2 | 26.7 | 25.1 | 27.4 | 28.0 | 26.5 | 29.3 | 18.9 | 26.1 | 25.4 | 34.6 | 27.8 | 20.6 |

| I agree | 44.9 | 43.1 | 43.4 | 50.0 | 45.5 | 47.6 | 43.2 | 45.3 | 45.3 | 45.9 | 40.4 | 49.7 | 44.5 | 45.7 | 46.2 | 43.8 | 46.9 |

| I strongly agree | 18.8 | 18.3 | 19.3 | 19.5 | 18.2 | 13.3 | 19.3 | 21.8 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 16.3 | 27.0 | 18.2 | 20.3 | 7.7 | 16.7 | 24.7 |

| Consumers are more likely to notice advertisements with controversial elements | |||||||||||||||||

| I strongly disagree | 1.3 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| I disagree | 9.4 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 10.1 | 12.4 | 9.9 | 6.7 | 11.2 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 4.4 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 7.2 |

| Neutral | 22.2 | 23.5 | 20.0 | 21.4 | 20.2 | 22.9 | 22.2 | 22.9 | 25.5 | 19.4 | 22.6 | 20.1 | 22.4 | 21.8 | 38.5 | 22.9 | 18.6 |

| I agree | 47.0 | 43.4 | 55.9 | 46.1 | 48.5 | 49.5 | 44.4 | 48.0 | 45.3 | 58.2 | 42.3 | 47.8 | 47.6 | 45.7 | 50.0 | 48.0 | 44.3 |

| I strongly agree | 20.1 | 22.0 | 14.5 | 21.4 | 21.2 | 13.3 | 21.4 | 21.8 | 17.4 | 12.2 | 21.6 | 25.8 | 19.8 | 20.8 | 11.5 | 16.7 | 28.4 |

| Controversial elements make advertisements better memorable | |||||||||||||||||

| I strongly disagree | 1.3 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| I disagree | 6.9 | 5.2 | 6.9 | 10.4 | 8.1 | 10.5 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 8.7 | 10.2 | 7.2 | 2.5 | 7.2 | 6.1 | 3.8 | 7.9 | 5.2 |

| Neutral | 24.8 | 26.3 | 25.5 | 20.8 | 27.3 | 21.9 | 23.5 | 26.8 | 24.8 | 27.6 | 29.8 | 16.4 | 25.4 | 23.4 | 34.6 | 26.1 | 20.6 |

| I agree | 43.0 | 39.8 | 46.2 | 46.8 | 36.4 | 46.7 | 46.1 | 40.2 | 46.0 | 42.9 | 36.1 | 49.1 | 42.2 | 44.7 | 50.0 | 41.9 | 44.3 |

| I strongly agree | 24.1 | 26.6 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 28.3 | 18.1 | 21.8 | 28.5 | 19.9 | 18.4 | 25.0 | 30.8 | 24.0 | 24.4 | 11.5 | 22.7 | 28.9 |

| Controversial methods of advertising are widely accepted and consumers are fond of them | |||||||||||||||||

| I strongly disagree | 6.5 | 7.6 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 6.3 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 5.9 | 8.2 |

| I disagree | 18.8 | 16.2 | 20.7 | 22.7 | 13.1 | 21.0 | 23.0 | 15.1 | 18.0 | 14.3 | 20.2 | 20.8 | 19.3 | 17.8 | 11.5 | 17.2 | 23.2 |

| Neutral | 35.9 | 37.3 | 34.5 | 34.4 | 40.4 | 42.9 | 31.3 | 35.8 | 46.0 | 28.6 | 34.1 | 32.7 | 35.9 | 36.0 | 50.0 | 36.9 | 32.0 |

| I agree | 30.8 | 29.4 | 33.1 | 31.8 | 38.4 | 27.6 | 28.8 | 31.3 | 27.3 | 39.8 | 31.3 | 28.3 | 31.9 | 28.4 | 30.8 | 32.0 | 28.4 |

| I strongly agree | 7.8 | 9.5 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 10.1 | 3.7 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 10.7 | 6.5 | 10.7 | 3.8 | 7.9 | 8.2 |

| Controversial methods of advertising stimulate interest in products | |||||||||||||||||

| I strongly disagree | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| I disagree | 13.6 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 16.2 | 13.1 | 17.1 | 14.0 | 11.2 | 18.0 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 8.2 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 11.5 | 16.0 | 8.8 |

| Neutral | 30.8 | 33.9 | 26.2 | 28.6 | 25.3 | 37.1 | 27.2 | 35.2 | 30.4 | 32.7 | 28.8 | 32.7 | 30.8 | 31.0 | 30.8 | 31.5 | 29.4 |

| I agree | 44.1 | 40.7 | 49.0 | 46.8 | 51.5 | 39.0 | 45.7 | 40.8 | 42.9 | 43.9 | 45.2 | 44.0 | 44.1 | 44.2 | 50.0 | 43.3 | 44.8 |

| I strongly agree | 9.4 | 10.7 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 4.8 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 14.4 |

| Controversial methods increase the prominence of advertisements | |||||||||||||||||

| I strongly disagree | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.5 |

| I disagree | 6.9 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 9.1 | 2.0 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 6.2 |

| Neutral | 25.9 | 29.4 | 25.5 | 18.8 | 25.3 | 30.5 | 23.5 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 24.5 | 30.8 | 19.5 | 25.4 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 27.3 | 22.7 |

| I agree | 48.2 | 44.6 | 54.5 | 50.0 | 56.6 | 45.7 | 44.4 | 50.3 | 49.1 | 49.0 | 43.3 | 53.5 | 47.6 | 49.7 | 57.7 | 47.3 | 49.0 |

| I strongly agree | 17.7 | 18.7 | 12.4 | 20.8 | 15.2 | 12.4 | 22.2 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 16.3 | 16.8 | 21.4 | 19.1 | 14.7 | 7.7 | 16.5 | 21.6 |

| In Recent Years, Controversy Has Been Present in Advertising More Frequently | Consumers Are More Likely to Notice Advertisements with Controversial Elements | Controversial Elements Make Advertisements Better Memorable | Controversial Methods of Advertising Are Widely Accepted and Consumers Are Fond of Them | Controversial Methods of Advertising Stimulate Interest in Products | Controversial Methods Increase the Prominence of Advertisements | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | |

| Sector (Kruskal-Wallis Test) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Production | 307.94 | 1.349 | 0.509 | 313.31 | 0.125 | 0.939 | 317.74 | 0.445 | 0.801 | 317.66 | 0.502 | 0.778 | 311.95 | 0.573 | 0.751 | 309.97 | 1.730 | 0.421 |

| Trade | 311.61 | 310.15 | 310.35 | 312.34 | 322.47 | 305.38 | ||||||||||||

| Services | 327.08 | 317.06 | 307.45 | 305.77 | 308.34 | 328.64 | ||||||||||||

| Enterprise size (Kruskal-Wallis Test) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Up to 9 employees | 310.49 | 3.685 | 0.298 | 322.44 | 4.070 | 0.254 | 317.44 | 3.756 | 0.289 | 332.89 | 3.627 | 0.305 | 320.28 | 5.424 | 0.143 | 326.81 | 5.420 | 0.144 |

| 10 to 49 employees | 293.69 | 286.30 | 290.37 | 305.48 | 278.30 | 280.40 | ||||||||||||

| 50 to 249 employees | 309.69 | 311.99 | 309.78 | 300.54 | 321.04 | 322.72 | ||||||||||||

| Over 249 employees | 331.96 | 326.56 | 329.94 | 325.07 | 320.16 | 313.03 | ||||||||||||

| Range of operations (Kruskal-Wallis Test) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Local | 303.27 | 20.303 | 0.000 | 297.45 | 7.034 | 0.071 | 300.93 | 15.749 | 0.001 | 298.05 | 3.677 | 0.299 | 290.76 | 4.777 | 0.189 | 308.56 | 7.507 | 0.057 |

| Regional | 298.94 | 305.05 | 285.99 | 340.49 | 308.43 | 307.01 | ||||||||||||

| National | 288.83 | 306.90 | 301.41 | 313.97 | 321.64 | 297.06 | ||||||||||||

| International | 365.11 | 343.60 | 358.99 | 311.90 | 329.00 | 344.01 | ||||||||||||

| Capital structure (Mann-Whitney Test) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Polish | 309.14 | −0.946 | 0.344 | 313.99 | −0.107 | 0.915 | 311.16 | −0.506 | 0.613 | 311.30 | −0.468 | 0.640 | 312.62 | −0.192 | 0.848 | 318.16 | −1.023 | 0.306 |

| Foreign/mixed | 322.99 | 312.43 | 318.60 | 318.28 | 315.42 | 303.36 | ||||||||||||

| Market position (Kruskal-Wallis Test) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Weak | 268.83 | 11.019 | 0.004 | 294.46 | 9.567 | 0.008 | 279.88 | 6.461 | 0.040 | 319.56 | 2.257 | 0.324 | 327.13 | 8.108 | 0.017 | 292.19 | 4.338 | 0.114 |

| Average | 300.91 | 299.81 | 303.75 | 320.52 | 299.41 | 305.05 | ||||||||||||

| Strong | 345.83 | 344.70 | 338.41 | 297.99 | 341.16 | 334.04 | ||||||||||||

| TOTAL | Sector | Enterprise Size | Range of Operations | Capital Structure | Market Position | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Trade | Services | Up to 9 Employees | 10 to 9 Employees | 50 to 249 Employees | Over 249 Employees | Local | Regional | National | International | Polish | Foreign/mixed | Weak | Average | Strong | ||

| Yes, we apply the principles of the Code of Ethics in Advertising in our advertising activity | 51.3 | 52.3 | 51.7 | 48.7 | 35.4 | 48.6 | 53.5 | 58.7 | 38.5 | 46.9 | 55.8 | 61.0 | 46.6 | 61.4 | 26.9 | 47.0 | 63.4 |

| No, we do not see the need to apply the principles of the Code of Ethics in Advertising in our advertising activity | 26.0 | 26.3 | 21.4 | 29.9 | 31.1 | 26.7 | 25.9 | 22.9 | 28.6 | 33.7 | 24.0 | 21,4 | 28.0 | 21.8 | 19.2 | 29.3 | 20.1 |

| No, we do not know the Code of Ethics in Advertising | 22.7 | 21.4 | 26.9 | 21.4 | 33.3 | 24.8 | 20.6 | 18.4 | 32.9 | 19.4 | 20.2 | 17.6 | 25.4 | 16.8 | 53.8 | 23.6 | 16.5 |

| Pearson’s chi-square | Test value χ2 | 3.833 | 15.981 | 23.744 | 12.185 | 29.317 | |||||||||||

| Df | 4 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Critical significance level p | 0.429 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| V-Cramer | - | 0.113 | 0.138 | 0.140 | 0.153 | ||||||||||||

| In Recent Years, Controversy Has Been Present in Advertising More Frequently | Consumers Are More Likely to Notice Advertisements with Controversial Elements | Controversial Elements Make Advertisements Better Memorable | Controversial Methods of Advertising Are Widely Accepted and Consumers Are Fond of Them | Controversial Methods of Advertising Stimulate Interest in Products | Controversial Methods Increase the Prominence of Advertisements | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | (A) | (B) | (C) | |

| Yes, we apply the principles of the Code of Ethics in Advertising in our advertising activity | 332.02 | 9.528 | 0.009 | 232.38 | 2.374 | 0.305 | 331.86 | 9.274 | 0.010 | 303.50 | 9.189 | 0.010 | 313.81 | 6.831 | 0.033 | 321.75 | 4.885 | 0.087 |

| No, we do not see the need to apply the principles of the Code of Ethics in Advertising in our advertising activity | 282.08 | 299.83 | 282.44 | 348.50 | 336.89 | 288.49 | ||||||||||||

| No. we do not know the Code of Ethics in Advertising | 307.71 | 306.85 | 307.65 | 295.94 | 285.95 | 323.56 | ||||||||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bachnik, K.; Nowacki, R. How to Build Consumer Trust: Socially Responsible or Controversial Advertising. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072173

Bachnik K, Nowacki R. How to Build Consumer Trust: Socially Responsible or Controversial Advertising. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072173

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachnik, Katarzyna, and Robert Nowacki. 2018. "How to Build Consumer Trust: Socially Responsible or Controversial Advertising" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072173

APA StyleBachnik, K., & Nowacki, R. (2018). How to Build Consumer Trust: Socially Responsible or Controversial Advertising. Sustainability, 10(7), 2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072173